Abstract

Poor pesticide handling practices and risk-awareness among African farmers puts human health and the environment at risk. To investigate information available to farmers in Zanzibar (Tanzania), an interview study was conducted with retailers, and governmental pesticide importation to Zanzibar was examined. Pesticide retailers in Zanzibar did not have the necessary knowledge to safely handle or to advise farmers on proper use of pesticides. Licensed shop owners were rarely found in the shops; instead, untrained personnel were employed to sell the pesticides. Implementation of the legislation was weak, mainly due to lack of surveillance by governmental institutions. Poor governmental importation practices and unregulated private imports indicate serious weakness in the management of pesticide importation in Zanzibar. The situation calls for increased attention on the monitoring of pesticide importation and sales to protect the health of farmers and retailers, as well as the environment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0338-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tanzania, Legislation, Interview study, Pesticide retailer

Introduction

The need for a sound pesticide management system becomes ever more important with an increasing use of agrochemicals. This is the case in African countries, where pesticides are expected to play an important role in the attempts to enhance crop yields in the future (WHO 1990). Weak legislations and regulations expose people and the environment to the side effects of pesticides (Ecobichon 2001), and it is often the poorest people that, indirectly, are most negatively affected by weak institutions (WDR 2002). Several studies from Africa have demonstrated very poor pesticide handling practices and risk-awareness among farmers, which inevitably puts humans and animals at risk (Mmochi and Mberek 1998; Sibanda et al. 2000; Stadlinger et al. 2011).

In Tanzania 80 % of the population is involved in agricultural activities, where the majority of the pesticides are used (Mmochi and Mberek 1998). The pesticide legislation in Tanzania requires that all pesticide importation, manufacture, and sale must be permitted by the Tropical Pesticide Research Institute (TPRI) (Lekei and Mndeme 1999). However, the implementation of the legislation of pesticide import and sale is poor (Mmochi and Mberek 1998; Macha et al. 2001; Ak’habuhaya 2005; AGENDA 2006). For instance, the actual pesticide import in the beginning of the 1990s was approximately twice the authorized amounts (Mmochi and Mberek 1998). The most recent import data for Tanzania mainland is from 1997 (Lekei and Mndeme 1999) and for Zanzibar in 2000 (Mmochi 2005). The development during the last decade has, to our knowledge, not been described.

During the 1990s, the number of licensed pesticide retailers in Tanzania increased from 2 in 1988 to 160 in 1997 (Lekei and Mndeme 1999; Macha et al. 2001), most likely as an effect of the removal of governmental subsidies during this period. Retailers play a key role in reducing risks from pesticide use, as in some areas they are the only persons that can provide farmers with product information. Governments are in fact enjoined to “develop regulations and implement licensing procedures relating to the sale of pesticides, so as to ensure that those involved are capable of providing customers with sound advice on risk reduction and efficient use” (FAO Code of Conduct 8.1.1 2003). Without such sources of information, farmers in many cases will rely on pesticide labels and pesticide pictograms as the only source of information, which have been shown to be difficult to interpret and comprehend (e.g., Rother 2008). Also, pesticide retailers themselves are at significant risk of illness due to frequent exposure to pesticides when they are not handled with caution (Kesavachandran et al. 2009). A few reports by employees of the Tropical Pesticides Research Institute (TPRI) and non-governmental organizations have described similar problems with pesticide shops of Tanzania Mainland, such as lack of registration, unqualified staff, repacking of pesticides and that pesticides are sold together with consumable products (Macha et al. 2001; Ak’habuhaya 2005; AGENDA 2006). Therefore, it has been suggested that the pesticide regulatory authorities in Tanzania are not operating effectively (Kaoneka and Ak’habuhaya 2000). Despite the fact that farmers in Zanzibar lack knowledge or resources to manage pesticides safely (Stadlinger et al. 2011), there are no studies on pesticide sales management or transfer of pesticide knowledge to users reported from Zanzibar.

The aim of this study was to investigate the information available to farmers in Zanzibar (Tanzania) to ensure a safe and effective use of pesticides. The retailers’ and distributors’ knowledge of pesticides, and their role in the enhancement of safe pesticide handling practices by farmers, was investigated to ascertain their effectiveness as an important information source for farmers, as prescribed by FAO guidelines (FAO 2003). The pesticide legislation concerning distribution, retail, and implementation was analyzed to discover whether the legislation in force is sound, and if the authorities actually manage to implement the legislation, and thereby protect pesticide users from hazards. The development of governmental pesticide importation the last decade and the import statistics in Zanzibar were investigated in detail and compared with the trends during 1990s observed by Mmochi and Mberek (1998).

Materials and Methods

Description of Study Area

Unguja Island, hereafter referred to as Zanzibar, is the largest island in the Zanzibar archipelago and a part of the United Republic of Tanzania. The major sources of income are fishing and agriculture, and 34 % of Zanzibar is agricultural land (NLUP 1995). The major crops grown in the area are clove, coconut, spice crops, fruits (mango, citrus), rice, and sugar cane (NLUP 1995). The annual population growth is 3 %, and small-scale agriculture is expected to continue to be an important source of income for the population (NLUP 1995).

Interviews with Retailers and Distributors

Preparation of Questionnaires

Interviews with the pesticide retailers were performed to assess their knowledge, how they contributed to spreading information about pesticides to farmers, and how pesticide distribution from distributors to retailers to farmers took place. Another purpose of the interviews was to shed light on the implementation of the legislation. The interviews contained information on retailers’ risk-awareness, pesticide handling and sales practices, the state of pesticide shops, purchase information and information given to customers.

Interviews and Sampling

The interviews were conducted face-to-face with the retailers in their working places in Zanzibar (22 interviews), and in Dar es Salaam (8 interviews). Furthermore, five persons holding different positions in pesticide importing and distributing companies were interviewed. Interviews with retailers were held in Swahili, with a translator, while interviews with the distributors were held in English. The shops were identified by talking to local authorities and local inhabitants, including the retailers who could point out the other pesticide shops in their village/township. Snowball sampling, where new respondents were identified through other respondents during the survey, was used since no records of the sampling group were available to select from. The only criterion for being included in the survey was selling agrochemical pesticides. This criterion excluded many small shops that were selling fumigants for indoor use or rat poison. All identified shops selling agro-pesticides in Zanzibar were visited, and interviews with retailers were held in all, except for three shops (Mail Nne, Kiembe Samaki, and Mahonda). During the interviews any observations of, for example, pesticide handling practices or pesticide sales were also noted. The survey was carried out from September to November, 2009.

Interview Analysis

Reponses were sorted into categories, based upon the range or type of answers received, and analyzed further. Interviews with retailers and distributors in Dar es Salaam were only summarized as background information.

Legislative Framework of Pesticides in Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar

There are two acts regulating pesticides in Tanzania; the Tropical Pesticides Research Institute Act from 1979 that led to the creation of the Tropical Pesticides Research Institute (TPRI), and the Plant Protection Act from 1997 which covered the protection of plants more generally. The Plant Protection Act—Part III (1997) replaced the Pesticides Control part V in the older Tropical Pesticides Research Institute Act (1979), covering the distribution and sale of pesticides. In this new act pesticides are referred to as “plant protection substances”. From these acts, two regulations have been created; the Pesticides Control Regulations from 1984, that in turn was replaced, in 1998, by the Plant Protections Regulations following the new Plant Protection Act.

These acts and regulations were examined with emphasis on the importation, distribution, and sales of pesticides, as well as the licensing of retailers. The analyses of the interviews were put in the context of the reviewed acts and regulations to examine the situation of the pesticide end-users in Zanzibar.

Although Zanzibar belongs to the United Republic of Tanzania, it is semi-autonomous and has its own legislation in several areas, including agriculture. Zanzibar follows the TPRI in many issues concerning pesticides, such as approval and registration of pesticides, and imports the majority of its pesticides from Tanzania (Head of Zanzibar Plant Protection Office, ZPPO, pers. comm.), but has its own legislative system. The manufacture, importation, wholesale and retail of pesticides in Zanzibar is regulated by the Zanzibar Food, Drug and Cosmetics Board (ZFDB) established by The Zanzibar Food and Drug and Cosmetics Act (ZFDC, No. 2 of 2006). The complying regulation is the Pharmaceutical Products, Herbal Products, Poisons and Pesticides Regulation from 2008.

The TPRI is responsible for licensing shops selling pesticides in mainland Tanzania. In Zanzibar, the Zanzibar Food, Drug and Cosmetics Board (ZFDB) has the equivalent function. Unlike the TPRI, however, the composition of this Board is not specialized in pesticides. The word ‘pesticide’ is not even mentioned in the ZFDC Act (pesticides are included under poisons), only in the Regulation, since its focus is on health, with health-related competences constituting the majority of the Board. Licenses for selling poisons (including pesticides) may be issued after approval of the Registrar or Assistant Registrar of ZFDB. All shops selling agricultural pesticides in Zanzibar are in need of a license from the ZFDB (Chief Drug Inspector, ZFDB, pers. comm.). The Board has a list of a few excepted pesticides (mainly insect repellents) that can be sold in any shop without a license (ZPPO and Ministry of Agriculture, pers. comm.). The Zanzibar Plant Protection Office (ZPPO) is the main governmental importer of agricultural pesticides to Zanzibar, following the list of registered pesticides by the TPRI (Head of PPD, pers. comm.). Private persons and businesses can also import pesticides but have to apply for an import permit from the ZFDB. The statistics of governmental import of pesticides and protective equipment, written down by hand by ZPPO officers in notebooks from 1988 to 2010, was compiled from the ZPPO port office in May 2010.

Results

Retailer Interviews

Pesticide Shops

Three different kinds of shops selling pesticides were identified in Zanzibar: (i) governmental shops with workers employed by the government, (ii) Participatory Agricultural Development and Empowerment Project (PADEP) shops owned by village cooperatives, selling mostly agricultural products, and (iii) private shops (including pharmacies) often selling human medicine, hygiene products, and pesticides in combination (Table 1). Among the eight private shops visited, only four were registered for selling pesticides (Table 1). In some of the private shops, non-agricultural products (such as human medicine, hygiene products) were sold and stored in the same room as pesticides (Table 1).

Table 1.

Villages where shops selling agrochemicals in Zanzibar Island were identified, divided into district location and shop type

| District | Type of shop | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Governmental | PADEP | Private | |

| Central | Jendele, Koani | Bungi, Bambi, Dunga, Mitakawani, Kikungwi, Kiboje, Machui | Mpapaa, b |

| Urban | Zanzibar Port | Amanib, Magomenia, b, Mwembeladua | |

| North | Kinyasini, Mahonda | Pale, Bumbwisudi, Mahonda | |

| South | Makunduchi | ||

| West | Kianga, Kombeni | Jumbi, Mail Nne, Kiembe Samaki | |

aDenotes that they were not registered according to Registrar of Zanzibar Food, Drug and Cosmetics Board (ZFDB), b Denotes that the stores were selling pesticides in combination with non-agricultural products, e.g., human medicine and hygienic products

Three shops were located in Zanzibar town, where two functioned both as wholesalers and retailers. One shop had been selling pesticides for less than 1 year, 13 shops between 1 and 3 years and the remaining six for more than 5 years, a few even longer than 10 years.

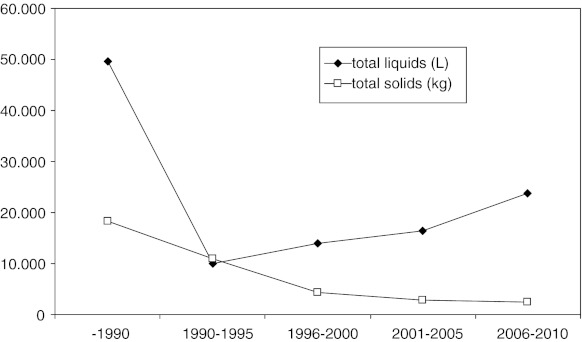

The most requested pesticides in Zanzibar were liquid formulations containing endosulfan, cypermethrin/imidacloprid, and lambda-cyhalothrin (Table 2) (for a complete compilation of recorded substances in the shops see Electronic Supplementary Material, Appendix I). This corresponds to the governmental import trends of Zanzibar where liquid pesticides were increasing, whereas solids have been decreasing steadily over the last 20 years (Fig. 1). According to the retailers, farmers’ demands were the only factor that determined which pesticides were kept in stock. All retailers believed that the pesticide sales were increasing or would increase in the future. The reasons given for the expected increase were the increasing number of vegetable farmers, increased abundance of pest organisms, and that pesticides, nowadays, were perceived as a requirement to obtain a good harvest, or any harvest at all. Besides the governmental shops that were provided with pesticides by the Zanzibar Plant Protection Office (ZPPO), the retailers in Zanzibar mentioned that pesticides also could be purchased in, for example, Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar Town (for village shops), and Arusha in northern Tanzania.

Table 2.

General information of pesticide shops where interviews were held and background information on pesticide retailers in Zanzibar

| Variable | Zanzibar |

|---|---|

| Products sold | n = 21 |

| Pesticides | 100 % |

| Livestock medicine | 71 % |

| Protective equipment | 10 % |

| Other agricultural products (fertilizers, seeds, feed…) | 76 % |

| Non-agricultural products (human medicine, hygiene products…) | 24 % |

| No. of years pesticides have been sold in shop | n = 21 |

| <1 year | 5 % |

| 1–5 years | 67 % |

| 6–10 years | 10 % |

| >10 years | 18 % |

| Most sold pesticides | n = 21 |

| Thionex 50EC (endosulfan) | 67 % |

| Attakan C344 (cypermethrin, imidacloprid) | 52 % |

| Karate 5EC (lambdacyhalothrin) | 29 % |

| Repacking of pesticides | n = 21 |

| Yes | 71 % |

| No | 29 % |

| Level of educationa | n = 22 |

| Primary | 14 % |

| Secondary | 77 % |

| Higher education | 9 % |

| Type of pesticide training | n = 22 |

| Informal training by shopkeeper | 14 % |

| Training from government | 41 % |

| Training from college/university (not necessarily pesticide specific) | 18 % |

| Long experience | 4 % |

| No training | 23 % |

| Position in shop | n = 22 |

| Employed | 64 % |

| Owner/Expert | 13 % |

| Part of shared ownership | 23 % |

| Time in shop | n = 22 |

| <1 year | |

| 1–5 years | 68 % |

| 6–10 years | 5 % |

| >10 years | 27 % |

aTanzania school system: primary school (1–7 years), secondary school (1–4 years)

Fig. 1.

Imported pesticides to Zanzibar by the Zanzibar Plant Protection Office (ZPPO) 1988–2010 (May), divided into total amounts of liquids and solids

Generally the governmental shops visited in Zanzibar were in a poorer state than other shops. For instance, one governmental shop was located in a large metal container placed in a field (Fig. 2). The shopkeeper complained that pesticides could not be sold after 10 a.m., because the fumes became too strong with the increasing temperature and lack of ventilation. A few shops had obvious spillage on the floor from repacking pesticides into smaller quantities (Fig. 3). Some private shops were selling pesticides as well as human medicine, animal health products, and hygiene products (Table 2). The PADEP shops were of varying standards, some of which were selling all different kinds of products (including handicraft, bicycles, etc.), while others were solely selling pesticides and other agricultural products.

Fig. 2.

Governmental shop in Zanzibar Island located in a metallic container. During daytime the shop is closed as the container gets too warm and filled with hazardous pesticide fumes. Inside the container the pesticide packages are opened, repacked, and sold in smaller quantities to the farmers. Photos: N. Stadlinger

Fig. 3.

Governmental shop in Zanzibar Island showing spillages on the floor as a result of repacking pesticides. In the room next to the shop premises they have their pesticide storage. Photos: N. Stadlinger

Pharmacies/private shops had a variety of customers, while shops mainly dealing with pesticides were frequented by farmers and livestock keepers. The centrally located shops in Zanzibar town received customers from all parts of the island while shops in the villages were mainly visited by local farmers.

Pesticide Retailers

The median age of the Zanzibar pesticide retailer was 35 years. The youngest person (14 years old) was found in a private shop, while the age generally was higher amongst the employees in the governmental shops. Both sexes were represented, but there were slightly more men than women working as retailers. The majority of the retailers had studied a few years in, or completed secondary school (Table 2).

Only four of the 22 interviewed retailers had a higher education or formal education regarding pesticides at college level, of which one was a pharmacist and one a veterinarian. However, they did not deal with customers on a regular basis. The remaining retailers had received an informal training from the shopkeeper, training through the PADEP program or ZPPO or were lacking training completely (Table 2). Apart from the governmentally employed retailers, all of whom had worked more than 10 years in their shops, most retailers in Zanzibar had held their job between 1 and 5 years.

Most retailers opened the original packages and sold smaller quantities of pesticides to the farmers. Only six (out of 22) retailers, mainly in stores with a more central location in Zanzibar Town, did not open sealed packages. The package size requested depended on the type of farmer, but in general, most farmers preferred to buy smaller amounts, to pay smaller sums per occasion (50–1000 TZS, equivalent to 0.03–0.7 USD; Stadlinger et al. 2011). Original bottles were sold for approximately 5000–15 000 TZS (1–3.50 USD) depending on size and substance.

As a majority of the retailers sold smaller quantities of pesticides to the farmers, most were at risk of direct exposure to the pesticides. Only half of the retailers stated that they were wearing some kind of protective gear such as gloves or mask when repacking and handling the pesticides. One person wore a simple mask on occasions and another respondent used protective gear when he was provided with it by the ZPPO. To demonstrate the extent of this problem, the total amounts of governmentally imported protective equipment to Zanzibar during 22 years (1988–2010) included 155 gloves, 120 masks, 100 pair of goggles, 71 pairs of gumboots, and 20 overalls.

Several retailers mentioned possible side effects of pesticides, mostly human health effects; a few stated that overuse could damage the crops, but none that it could have negative effects on non-targeted organisms in the environment. Most retailers knew that it was poisonous but could not define any effects. Their understanding of pesticide exposure pathways was rather low and only five retailers were aware of pesticide poisoning symptoms, of these they mentioned: coughing, skin irritation, head ache, dizziness, lung problems, eye problems, vomiting, loss of body weight, cancer, and diarrhea.

The safety equipment found in the shops included boots, mask, gloves, water, and soap/detergent. Some of the shops had no access to running tap-water but relied on a bucket of water, or a tap outside of the shop. None of the retailers had an eyewash bottle or antidote to exposure, which are recommended contents of a pesticide first-aid kit (Lekei and Mndeme 1999). In case of a pesticide poisoning, most indicated that they would go to hospital. Some retailers suggested that one should provide milk or provoke vomiting to poisoned persons before sending one to hospital.

Retailers and Distributors/Importers in Dar es Salaam

The interviews with retailers in Dar es Salaam clearly illustrated how the centrally located shops were acting as important centers of pesticide sales for other parts of the country (including Zanzibar) and even other East African countries. The Kariakoo market house was the central point for pesticide sales, with about 15 shops in the building selling pesticides and other agricultural equipment.

Dar es Salaam has several distributing and importing companies. There are more than 142 pesticide importing companies in Tanzania (AGENDA 2006). Representatives of five companies in Dar es Salaam were interviewed with focus on pesticide retailing at a national level. Every company had several branches in the country.

Low knowledge amongst retailers was a recurring topic that was seen as a problem by several of the companies. Most of the companies were active in educating retailers and agricultural extension officers through programs called “training of trainers” that would extend information to farmers. Other ways to provide the farmers with information included demonstration trial plots, seminars, distribution of planting and spraying calendars and leaflets, as well as marketing campaigns in rural areas. Only one company was importing and selling protective equipment, but the market was low and therefore most face masks were sold to the industry instead.

All interviewed persons at the distribution and importing companies expected a future increase in pesticide sales in Tanzania.

Discussion

Pesticide Sales and Import

Deficiencies amongst Tanzanian pesticide retailers have been divided into three different categories by the TPRI; very serious (no permit to sell pesticides, selling of repacked pesticides, untrained personnel, poor ventilation, spills), serious (no protective clothing, no fire extinguisher, no first-aid kit, selling pesticides with other things in the shop, no facilities for washing hands), and somewhat serious (expired permit to sell pesticides, no warning signs, no records of sales, poisoning cases) (Ak’habuhaya 2005). According to this categorization, most of the pesticide shops visited in this study had serious and very serious deficiencies, and the retailers did not possess adequate knowledge to function as a source of information on safe pesticide use to farmers.

Regulations in both Tanzania and Zanzibar state the importance of proper use of protective gear when handling pesticides. However, only very few retailers were using protective gear when repacking pesticides, and thus, indirectly conveying the message to the farmers that pesticides are not hazardous. Very low quantities of protective gear were imported by the distributors in mainland Tanzania and the Zanzibar Plant Protection Office (ZPPO). Little or no effort was put into implementing the use of protective equipment amongst retailers and farmers, despite the responsibility of the pesticide industry and governments to do so (FAO 2003), resulting in discouragingly low sales and use of protective gear.

The opening of original packages and selling smaller quantities of pesticides is considered very serious (Ak’habuhaya 2005). As the repacking was a natural part of the retailers’ everyday work and mostly performed without any protective equipment, the retailers were extensively exposed to pesticides. It is understandable that farmers request smaller and cheaper pesticide packages, but one could argue that it ought to be the responsibility of the pesticide industry to produce different package sizes that meet the needs of smallholders (FAO 2003). Only a few pesticides were imported in smaller packages or bottles by the ZPPO, although smaller quantities often are requested by the customers. Instead, powders and larger containers were generally repacked into smaller amounts by the ZPPO in Zanzibar port to meet the needs of customers.

The fact that the majority of the stores in Zanzibar had opened/started selling pesticides less than 3 years ago clearly indicates a recent expansion and an expected increase in pesticide sales. The retailers and distributors also predicted an increase of pesticide sales and use. However, the risks for human health and the environment will continue to increase, as long as pesticides are sold, handled and used by farmers and retailers with poor knowledge of these potentially very hazardous substances.

No governmental compilation and evaluation of pesticide import statistics for Zanzibar was found, and a similar situation seems to be present on the Tanzania mainland. This makes it difficult for the government to analyze the risks with the pesticide use, or to regulate the import of pesticides (FAO 2003). The import of the bio-pesticide Bacillus thuringiensis initiated in the beginning of the 1990s to replace the more hazardous substances (Mmochi and Mberek 1998) was stopped in 1997, probably as a result of a low demand and since then no bio-pesticide has been imported by the ZPPO. Other substances that were introduced at the same time, like Satunil, copper sulfate, and diazinon (Mmochi and Mberek 1998) are still being imported. Lindane, atrazine, and paraquat are no longer imported by the ZPPO, even though they were encountered several times in shops and amongst farmers on the island (Stadlinger et al. 2011), indicating a substantial private importation of these substances. Other clear changes that have occurred during the last decade include, for example, pyrethroids, like lambda-cyhalothrin, that have become increasingly popular and have replaced cypermethrin, and Satunil (propanil and thiobencarb) that has been imported from Thailand since 1994, has replaced the previously commonly imported herbicide Basagran (bentazone and dichlorprop) (Fig. 1; see Electronic Supplementary Material, Appendix IIa and IIb for a compilation).

The limited importation of protective equipment indicates that end-users (and retailers) are not actively encouraged to use protective gear, either by the government or the industry although it is even included in the legislation that pesticide suppliers also should provide and maintain such gear. Furthermore, the Zanzibar Plant Protection Office (ZPPO) was distributing and selling pesticides that possibly were expired and ineffective after many years of storage. A comparison between the governmental importation and pesticides recorded in pesticide shops of Zanzibar demonstrate a substantial private importation to the island. However, there is to our knowledge little control of such import. Therefore, no authority has the overview or control of all pesticide substances distributed in Zanzibar.

Pesticide Legislation and Its Implementation

The present study covered most pesticide retailers on Zanzibar Island selling agro-pesticides. The situation encountered in the shops did not comply with the legislation, i.e., similar situations were found in other areas of Tanzania (Macha et al. 2001; Ak’habuhaya 2005; AGENDA 2006).

Although the Tanzanian pesticide legislation is better than the Zanzibar scheme, since it is targeting pesticides in particular, the implementation of the legislation is not functioning well (Macha et al. 2001; Ak’habuhaya 2005; AGENDA 2006), highlighted by, amongst other issues, the unsafe practices in pesticide shops and retailers selling pesticides without licenses. The Zanzibar Food Drug and Cosmetics Act (2006) is not specialized in regulating pesticides, but mainly pharmaceuticals and other health-related substances and poisons, giving this problematic group of chemicals less attention than needed. Although repacking and selling of pesticides in non-original packages is restricted according to both Tanzanian and Zanzibar regulations, this occurred frequently in most shops. Since it is so commonly and openly done, it demonstrates that there is no control or issued penalties of this in either of the visited districts and that the retailers have no other alternatives to meet the farmers’ demands.

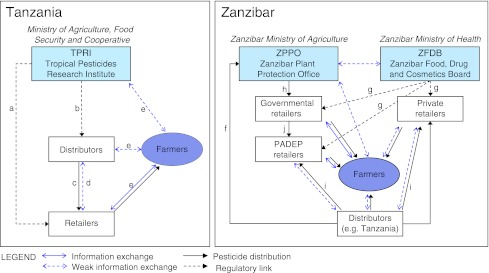

Even though Zanzibar, in many respects, is closely linked to the Tanzanian mainland when it comes to import and registration of pesticides, the two retailers’ licensing and distribution systems are distinct (Fig. 4). In mainland Tanzania the Registrar of the TPRI is responsible for issuing licenses for retailers (Fig. 4). The Registrar of the ZFDB is responsible for recommending the Board as to whether a retailer should be issued with a license for selling pesticides in Zanzibar. Thereafter the Board, which does not include any pesticide scientist, decides if any license should be issued (Fig. 4). Since the Board covers a wide variety of matters, from food quality control to pharmaceutical licenses, it is doubtful whether it has the time and expertise to assess the suitability of a retailer license applicant in detail.

Fig. 4.

Tanzania: The Ministry of Agriculture has delegated the responsibility for most areas concerning pesticides to the Tropical Pesticides Research Institute (TPRI) that is a key stakeholder in Tanzanian pesticide management. TPRI is linked to the private sector, retailers and farmers in several ways. Pesticide retailers get their license from TPRI (a). Pesticide importers need to get their products approved for registration by the TPRI before selling them on the market (b). The retailers buy pesticides from distributors and sell them to farmers (c). Retailers receive some training from the private sector, e.g., through Crop Life Tanzania (an umbrella organization for pesticide companies) that many distributors are members of (d). Farmers meet retailers, extension officers trained by the Ministry of Agriculture and the industry (e). To what extent farmers are in contact with the TPRI is unknown. Zanzibar: The Ministry of Agriculture has delegated the responsibilities for pesticide importation, governmental shops and extension services to the Zanzibar Plant Protection Office (ZPPO). ZPPO imports pesticides from distributors in Tanzania as well as other countries, e.g., Thailand (f). There are three types of pesticide retailers in Zanzibar; governmental retailers (employed by the ZPPO), PADEP retailers (agricultural cooperatives initiated by the Ministry of Agriculture) and private retailers. The responsibility for approving all pesticide retailers is under the Ministry of Health through the Zanzibar Food, Drug and Cosmetics Board (ZFDB) (g). ZPPO has its own governmental shops on Zanzibar, which they supply with pesticides (h). Similarly to the governmental retailers, the PADEP cooperatives are also a governmental initiative, and do like the governmental shops need a license from the ZFDB to sell pesticides. PADEP and private retailers buy pesticides from other retailers in Zanzibar or on mainland (i). PADEP shops also buy pesticides from governmental shops (j). Farmers in Zanzibar are in contact with different types of retailers, often depending on residence

The situation in the governmental shops in Zanzibar was particularly bad (Figs. 2, 3), despite the long experience of the employees, which indicates poor training and lacking monitoring by the ZFDB (Fig. 4). Pesticides are not permitted to be sold or stocked together with human medicine in Zanzibar. However, this was the case in all pharmacies visited in Zanzibar, even shops with a license from the Zanzibar Food, Drug and Cosmetics Board (ZFDB) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the license of four private retailers interviewed could not be confirmed by the Registrar of ZFDB, indicating a lack of surveillance from the Board.

In summary, the regulatory institution for pesticide sales management in Zanzibar (ZFDB) was found to be too weak to meet its obligation of controlling pesticide sales (Fig. 4). It is problematic that an institution specialized in pharmacology and food safety is responsible for licensing and surveillance of shops selling agrochemicals, since necessary pesticide knowledge might be lacking and the information exchange with the ZPPO is weak (Fig. 4). Also, the institution importing agricultural pesticides to Zanzibar, ZPPO, did not compile and evaluate the import. It has been suggested to give TPRI in Tanzania mainland the full mandate of pesticide management and regulation to improve the system (where the responsibilities today are divided between several stakeholders) (ESAANet 2011) and a similar system could be applicable for Zanzibar. Compared to the vast regions of Tanzania mainland, Zanzibar Island is relatively small. With clear responsibilities and proper issuing of retailer licenses, monitoring should be manageable in Zanzibar.

Pesticide retailers have an important role in mediating information on safe pesticide handling by farmers (Fig. 4) since retailers are often the only persons that farmers are in contact with who can advise them on pesticide use, especially as the contact with agricultural extension officers often is limited (Stadlinger, unpubl.). Although there is no or very limited information transferred from retailers to farmers there were no incentives encouraging retailers to give information to farmers, and there seemed to be no controls or monitoring of retailers by governmental institutions.

There is a similar situation with regard to the lack of information and poor communication between providers and users in, for example, the management of sexually transmitted infections in Tanzania. Also in this parallel case it has been concluded that drug-sellers could play an important role in the management if they were given appropriate training and tools. At present, advice is rarely given and dosage regimens provided are often inaccurate (Viberg et al. 2009). Similarly, pesticide retailers could provide an important educational function for farmers, if the licensing of retailers and pesticide sales was stricter and better monitored.

One recurring problem found in the pesticide shops, was that the individual retailers that had been licensed to sell pesticides (by ZFDB) were not present in the shops (Fig. 4). The business was often completely carried on by family members or employees that were not trained enough to safely handle pesticides or give sound advice to farmers. The information exchange between pesticide distributors and retailers was also weak (Fig. 4): where persons working for distribution companies were well-informed, but little of that knowledge reached their major group of customers, the retailers.

Major pesticide companies benefit from a weak pesticide regulatory system, for example, which enables the distribution of pesticides that have been banned for a long time in Europe and USA (e.g., Smith et al. 2008). The pesticide industry has a lot of money to invest in advertising pesticides to farmers and there is no source that may provide farmers with unbiased information. The chemical industry may therefore benefit from the present situation with uneducated retailers and farmers. Even if the industry has a responsibility in promoting the proper use of pesticides (FAO 2003), other less biased ways would be beneficial for the farmers and retailers, where companies should pay part of the profits to funds that work with educational programs, instead of educating retailers and farmers themselves (Fig. 4).

Evaluative studies of pesticide management (import and distribution) in African countries are scarce in the scientific literature. However, some efforts were made in the Pesticide Policy Project (1994–2001) in collaboration with Hannover University, where pesticide import and distribution in Zimbabwe and Mali was evaluated to different extents (Mudimu et al. 1999; Ajayi et al. 2001). The Pesticide Action Network conducted sub-studies in Benin, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Senegal to assess changing patterns of pesticide supply and distribution, due to the removal of governmental subsidies and the effects on smallholders, in 2000–2001 (Williamson 2003). Even though these studies are more than a decade old and changes may have occurred in pesticide importation and use since that time, there are several parallels with the Zanzibar case as seen today. Even though pesticide legislations have developed in all the investigated countries, the monitoring of importation, sales and use is very weak in all of them. In Zimbabwe, the monitoring seems to be the weakest. No regulation deals with pesticide importation by individual farmers (Mudimu et al. 1999). A common problem in some African countries is incomplete import data, that often overlook private importation and donations, and therefore does not correspond to the actual use (Williamson 2003). Similarly to Tanzania, governmental subsidies on pesticides were removed in the beginning/mid 90s in several other African countries and thereafter the farmers have mainly purchased pesticides from private companies (Williamson 2003). In all the studied countries (Benin, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Senegal), informal supply channels by non-licensed retailers were significant and often preferred since they were readily accessible, but also because they offered repacked pesticides in smaller amounts (Williamson 2003). In Zanzibar the formal supply channels (governmental shops) also provide repacked unlabeled pesticides, although it is against the existing legislation (illustrated in Figs. 2, 3). Thus, it is a common problem to meet the needs of the farmers and offer small, labeled packages of pesticides for affordable amounts of money. Continuous studies and follow-up studies are needed on a regional level to monitor and predict coming trends in pesticide distribution and use in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This study identifies a non-functioning regulation of pesticide importation and sales in Zanzibar, manifested as a lack of knowledge both amongst retailers (this study) and farmers (Stadlinger et al. 2011). With weakly run governmental institutions, pesticides are sold by untrained retailers that are unable to provide farmers with sound pesticide risk information in accordance with the FAO guidelines (2003). With too little knowledge at hand, repacking of pesticides is perceived to be an option in the absence of better alternatives that puts not only farmers’ but also the retailers’ health at risk through daily exposure to a variety of hazardous pesticides.

Conclusions

Most pesticide retailers in Zanzibar Island do not possess the necessary knowledge to safely handle or advise farmers on proper pesticide use, possibly due to lack of appropriate training and information from the government. With little available pesticide information from the government to farmers, it is essential that the licensing of retailers is better controlled and managed than at present to ensure proper advice to farmers from retailers. In Zanzibar, the non-specific pesticide legislation, in combination with the absence of monitoring retailers, creates a weak foundation for the control of pesticides. Furthermore, a lack of digital records of pesticide importation to the island, as well as an unregulated private importation, makes it difficult to evaluate the risks with pesticide use. The increasing pesticide sales trend across the country calls for stronger attention to the regulation of pesticide importation and sales in order to avoid human health problems and environmental exposures.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anders Sjögren for valuable discussions and input and Nils Kautsky, Ben Jaeschke and two anonymous reviewers for important comments on the manuscript. Rose Mwaipopo, Vera Ngowi, and Dorah Swai contributed with helpful advice and information. The translator Said Juma Shaaban alongside Aisha Dallu and Rajab Kiravu and our colleague Göran Samuelsson made the study possible to perform in the field. The authors are grateful to the Institute of Marine Sciences, Zanzibar. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to all the respondents for sharing their time with us. The study was financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).

Biographies

Nadja Stadlinger

is a doctoral candidate at the Stockholm University, Department of Systems Ecology. Her research interests include the management of socio-ecological systems in addition to ecotoxicology and ecological risk assessments.

Aviti J. Mmochi

is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Dar es Salaam, Institute of Marine Sciences. His research interests stretch from analytical chemistry and pesticide management as well as aquaculture and creating new livelihood opportunities in poor regions.

Linda Kumblad

is senior scientist at Stockholm University, Department of Systems Ecology. Her research interest includes integrated coastal zone management, systems ecology and ecological risk assessments. Her current research focuses on anthropogenic disturbances and their measures in coastal ecosystems in tropical as well as in temperate regions.

Contributor Information

Nadja Stadlinger, Phone: +468164362, FAX: +468158417, Email: nadja@ecology.su.se.

Aviti J. Mmochi, Email: mmochi@ims.udsm.ac.tz

Linda Kumblad, Email: linda@ecology.su.se.

References

- Pesticides and poverty. A case study on trade and utilization of pesticides in Tanzania: Implication to stockpiling. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: AGENDA; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, O., M. Camara, G. Fleischer, F. Haïdara, M. Sow, A. Traoré, and H. van der Valk. 2001. Socio-economic assessment of pesticide use in Mali. Special Issue Publication Series no. 6. The Pesticide Project, Hannover, Germany, 66 pp.

- Ak’habuhaya JL. Needs for pesticide safety outreach programs in developing countries: A Tanzanian example. African Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety. 2005;15:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ecobichon DJ. Pesticide use in developing countries. Toxicology. 2001;160:27–33. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(00)00452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESAANet, The East & Sothern Africa Agribusiness Network. 2011. Regulations. Retrieved 22 October, 2011, from http://ntwk.esaanet.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=212:the-tropical-pesticides-research-institute-act-1979-tpri-act&catid=52:regulations&directory=128.

- International Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of Pesticides (Revised Version) Rome: FAO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kaoneka BK, Ak’habuhaya JL. Pesticide management in developing countries. African Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety. 2000;10:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kesavachandran C, Pathak MK, Fareed M, Bihari V, Mathur N, Srivastava AK. Health risks of employees working in pesticide retail shops: An exploratory study. Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;13:121–126. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.58914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekei EE, Mndeme RR. Licensing and control of firms dealing with pesticides in Tanzania. African Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety. 1999;9:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Macha M, Rwazo A, Mkalanga H. Retail sale of pesticides in Tanzania: Occupational human health and safety considerations. African Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety. 2001;11:40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mmochi, A.J. 2005. Chemodynamics of Pesticide Residues and Metabolites in Zanzibar Coastal Marine Environment. PhD Thesis. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: University of Dar es Salaam.

- Mmochi AJ, Mberek RS. Trends in the types, amounts, and toxicity of pesticides used in Tanzania: Efforts to control pesticide pollution in Zanzibar, Tanzania. AMBIO. 1998;27:669–676. [Google Scholar]

- Mudimu, G.D., H. Waibel, and G. Fleischer, eds. 1999. Pesticide policies in Zimbabwe. Status and implication for change. Special Issue Publication Series no. 1. The Pesticide Project, Hannover, Germany, 222 pp.

- NLUP, National Land Use Plan. 1995. Appraisal: Analysis of potentials and issues. Report 2. Zanzibar Integrated Land and Environmental Management Project and Finnish International Development Agency—National Board of Survey, Zanzibar.

- Rother H-A. South African farm workers’ interpretation of risk assessment data expressed as pictograms on pesticide labels. Environmental Research. 2008;108:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibanda T, Dobson HM, Cooper JF, Manyangarirwa W, Chiimba W. Pest management challenges for smallholder vegetable farmers in Zimbabwe. Crop Protection. 2000;19:807–815. doi: 10.1016/S0261-2194(00)00108-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Kerr K, Sadripour A. Pesticide exports from U.S. ports, 2001–2003. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2008;14:176–186. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2008.14.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadlinger N, Mmochi AJ, Dobo S, Gyllbäck E, Kumblad L. Pesticide use and risk awareness among smallholder rice farmers in Tanzania. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 2011;13:641–656. doi: 10.1007/s10668-010-9281-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viberg N, Mujinja P, Kalala W, Kumaranayake L, Vyas S, Tomson G, Stålsby Lundborg C. STI management in Tanzanian private drugstores: practices and roles of drug sellers. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85:300–307. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Building institutions for markets. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press, The World Bank; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Public health impact of pesticides used in agriculture. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, S. 2003. Pesticide provision in liberalized Africa: out of control? Network Paper no. 126. Agricultural Research and Extension Network, London, UK, 15 pp.

- ZFDC, The Zanzibar Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act No. 2. 2006.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.