Abstract

Context

Inactivating mutations in the enzyme hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (H6PDH, encoded by H6PD) cause apparent cortisone reductase deficiency (ACRD). H6PDH generates cofactor NADPH for 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1, encoded by HSD11B1) oxo-reductase activity, converting cortisone to cortisol. Inactivating mutations in HSD11B1 cause true cortisone reductase deficiency (CRD). Both ACRD and CRD present with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation and adrenal hyperandrogenism.

Objective

To describe the clinical, biochemical and molecular characteristics of two additional female children with ACRD and to illustrate the diagnostic value of urinary steroid profiling in identifying and differentiating a total of six ACRD and four CRD cases.

Design

Clinical, biochemical and genetic assessment of two female patients presenting during childhood. In addition, results of urinary steroid profiling in a total of ten ACRD/CRD patients were compared to identify distinguishing characteristics.

Results

Case 1 was compound heterozygous for R109AfsX3 and a novel P146L missense mutation in H6PD. Case 2 was compound heterozygous for novel nonsense mutations Q325X and Y446X in H6PD. Mutant expression studies confirmed loss of H6PDH activity in both cases. Urinary steroid metabolite profiling by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry suggested ACRD in both cases. In addition, we were able to establish a steroid metabolite signature differentiating ACRD and CRD, providing a basis for genetic diagnosis and future individualised management.

Conclusions

Steroid profile analysis of a 24-h urine collection provides a diagnostic method for discriminating between ACRD and CRD. This will provide a useful tool in stratifying unresolved adrenal hyperandrogenism in children with premature adrenarche and adult females with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Introduction

Cortisone reductase deficiency (CRD) and apparent CRD (ACRD) are characterised by the failure to generate cortisol from inactive cortisone resulting in HPA axis activation and excessive ACTH-mediated adrenal androgen secretion, with ∼14 cases described clinically and biochemically in the literature (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Affected patients may present with premature adrenarche in childhood including pubarche, or as adolescents and adults with androgen excess and a PCOS-like phenotype in females (4, 5, 10). A 24-h urine collection subjected to urinary steroid analysis by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) shows characteristic elevations of cortisone metabolites (tetrahydrocortisone (THE)) relative to cortisol metabolites (tetrahydrocortisol (THF+5α-THF)) together with a decrease in 5α/5β tetrahydrocortisol. Additionally, metabolites of the androgenic precursors androsterone (An), etiocholanolone (Et) and DHEA/S are pathologically elevated.

The HSD11B1 gene encodes the enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1) that functions as an NADPH-dependent oxo-reductase within the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) converting inactive cortisone to active cortisol. Mutations in HSD11B1 explain CRD that leads to loss of cortisol regeneration and increased cortisol clearance with secondary activation of the HPA axis (5, 11). By contrast, ACRD is caused by mutations in the H6PD gene, which encodes the enzyme hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (H6PDH). In the ER, lumen H6PDH generates cofactor NADPH that is utilised by 11β-HSD1 for the conversion of cortisone to cortisol (4). Inactivation of H6PDH in mice and humans leads not only to the loss of 11β-HSD1 oxo-reductase activity but also to a gain of 11β-HSD1 dehydrogenase activity, with a profound switch to cortisol inactivation (4, 12). In recombinant mice lacking H6PDH and 11β-HSD1, the urinary steroid profile abnormality is more marked in H6PDKO mice compared with 11β-HSD1KO mice (13).

To date, we have identified two patients with CRD (boys aged 8 and 11 years) with significantly reduced THF+5α-THF/THE ratios of 0.16 and 0.22 (reference range 0.7–1.3). As for ACRD, we have identified four cases (one boy aged 6 years and three adult females) with an even more extreme biochemical phenotype typified by very low THF+5α-THF/THE ratios <0.05 (4, 5).

Here, we describe two new female cases aged 4 and 7 years presenting with premature adrenarche. Employing our GC/MS-derived biomarker panel and molecular genetic analysis, we establish a diagnosis of ACRD with novel mutations in H6PD in both patients, highlighting the first presentation of ACRD in female children. Furthermore, we define the diagnostic urinary steroid metabolite profiles differentiating CRD/ACRD and propose a diagnostic and therapeutic strategy for the clinical management of affected individuals to prevent potential long-term health problems including hyperandrogenism.

Materials and methods

Patients

Approval for all studies was obtained after seeking consent according to Local Institutional Review Board criteria. Both cases were minors and parental consent was obtained.

Case 1 was a 7-year-old girl of non-consanguineous Caucasian parents who presented with an 8-month history of premature pubarche with onset of pubic and axillary hair (Tanner P2, A2, B1), as well as increased height velocity. On examination, she was 24.9 kg (0.21 SDS) and 129.5 cm (0.95 SDS) in height. Her bone age was accelerated at 8.8 years. Central precocious puberty was excluded by a pre-pubertal response to a LHRH stimulation test (LH baseline: 0.2 mU/ml, 30 min 1.5 mU/ml; FSH baseline: 3.2 mU/ml, 30 min 8.5 mU/ml) and infantile appearance and volume (1.5 ml) of the uterus on ultrasound. However, adrenal androgens were elevated with a DHEA of 21.1 nmol/l (normal range (NR), 3.5–10.4 nmol/l) and androstenedione of 2.2 nmol/l (NR, 0.2–1.2 nmol/l).

Case 2 was a 4-year-old girl, the first child of non-consanguineous Caucasian parents, referred for investigation of premature pubarche. From the age of 3.5 years, she developed hair around the labia majora and a distinct change in body odour, with no acne or growth acceleration. On examination, she was 19.8 kg (1.2 SDS) and 108.5 cm in height (1.01 SDS), with Tanner stage 2 pubic hair, no breast development, no clitoromegaly and normal blood pressure. She had an accelerated bone age of 5 years. Her LH (<0.1 IU/l; NR, 0.1–0.4 IU/l) and FSH (1.3 IU/l; NR, 0.23–11.1 IU/l) were appropriate for age and not suggestive of central precocious puberty. Morning DHEAS (4.05 μmol/l; NR, 0.05–0.85 μmol/l) and androstenedione (1.9 nmol/l; NR, 0.2–1.2 nmol/l) were elevated but 17-OH-progesterone and ACTH were normal. Testosterone was undetectable and SHBG was decreased; 0900 h baseline cortisol was 90.2 nmol/l with an exaggerated response 60 min after cosyntropin stimulation (1.336 nmol/l; NR>550 nmol/l). At age 7 years, she had a slightly increased linear growth rate and advanced bone age of 9 years. DHEAS had increased to 9.72 μmol/l and androstenedione to 4.8 nmol/l. Adrenal ultrasound was normal.

Urinary steroid metabolite analysis

The two novel ACRD cases were assessed by urinary steroid profile analysis employing GC/MS of 24-h urine collections. They were then compared with the steroid profiles of the four previously described cases of ACRD and two cases of CRD (4, 5). Urinary steroid metabolite excretion was analysed employing a previously described GC/MS selected-ion-monitoring method (GC/MS-SIM) (4, 5, 9). In brief, steroids were enzymatically released from conjugation and, after extraction, chemically derivatised before GC/MS-SIM. Metabolites of the glucocorticoid series were THF, 5α-THF, α-cortol, α-cortolone, β-cortol, β-cortolone, THE and urinary cortisol and cortisone. Androgen metabolites were An, Et and DHEA. After quantification of steroid metabolites by GC/MS, we also calculated substrate/product metabolite ratios and ratios of cortisol or cortisone metabolites as an index of the in vivo activity of 11β-HSD1 (THF+5α-THF/THE and cortols/cortolones) and the 5α/5β-reductases (THF/5α-THF). As a measure of HPA axis activity, the sum of the glucocorticoid series was defined as total cortisol metabolite excretion (THFs+THE+cortols+cortolones+urinary cortisol+urinary cortisone) and total androgen excretion as the sum of androgen metabolites (An+Et+DHEA). Diagnostic ratios and the overall secretion patterns were compared with urinary steroid profiles obtained from a normal reference cohort of healthy children of different age groups (group 1: age 1–7 years, n=22, 12 boys and 10 girls; group 2: age 8–14 years, n=31, 13 boys and 18 girls) and adult females (age 18–63 years; n=82).

Molecular analysis of HSD11B1 and H6PD

PCR amplification of the coding region of both genes including exon/intron boundaries was performed using genomic DNA from both cases, as described previously (4, 5). We compared HSD11B1 sequences with GenBank entries for two overlapping clones covering chromosome 1q32.2–41, PAC 28010, PAC 43014 and H6PD sequences to clone RP3-510D11 on chromosome 1p36.2–36.3.

Mutagenesis and stable cell line generation

The QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, Cambridge, UK) was used to mutate WT H6PD cDNA, contained in pcDNA3.1D/V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen), to the respective alternative mutant sequences, with subsequent confirmation of the introduced mutations by direct sequencing. HEK293 cells were transfected with WT and mutant H6PD using a 293 cell-specific transfection reagent (Mirus, Birmingham, UK). Stably transfected cells were selected using G418 (Sigma) and, in each case, four clones from single-cell colonies were derived for WT and mutant enzyme studies.

RNA extraction RT-PCR

As described previously (4), total RNA was extracted from transfected cell lines using a single-step extraction method (Tri-reagent, Sigma) and 1 μg total RNA reverse transcribed to cDNA (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was assessed using pre-validated specific TaqMan gene expression assays and Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Expression levels were normalised to the housekeeping gene 18S in all.

H6PDH assay

H6PDH assays were performed on WT and mutant microsomes prepared from HEK293 cells by spectrofluorometric detection of NADPH generation as described previously (n=4 stable cell lines analysed in triplicate) (4).

Western blot analysis

Western blots were prepared by electroblotting 11% SDS–polyacrylamide gels onto Immobilon PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) at 100 V for 1 h in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine and 20% (v/v) methanol. Membrane was blocked in PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 and 20% (w/v) skimmed milk powder, washed and then incubated with anti-H6PDH polyclonal antibody in PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20. Membrane was then washed and incubated with secondary antibody diluted 1/25 000 in PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20. Detection was by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). Anti-calreticulin antibody was used as a loading control.

Results

Urinary steroid metabolite analysis of novel ACRD cases

Table 1 summarises the urinary steroid metabolite profiling of cases 1 and 2 and highlights the diagnostically important findings. In both cases, the metabolites of cortisol (THF, 5α-THF and the cortols) were below or at the lower end of normal, whereas the metabolites of cortisone (THE and the cortolones) were elevated above the normal reference range in all cases. To enhance interpretation of these individual metabolites, we calculated THF+5α-THF/THE and cortols/cortolones ratios and showed them to be grossly abnormal in both cases, falling to near zero and well below the normal reference range (Table 1). These data strongly indicate a defect in the conversion of cortisone to cortisol. As a consequence of the increased cortisol clearance, total glucocorticoid output is elevated in both cases above the normal reference range (Table 1). This also results in increased ACTH-mediated adrenal androgen output reflected in elevated levels of the androgen metabolites (An, Et and DHEA) in both cases (Table 1). From these urinary steroid profile data, it was concluded that the clinical and biochemical evidence were strongly suggestive of ACRD and warranted genetic examination.

Table 1.

Urine steroid metabolome of two novel ACRD cases.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Reference range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoid metabolites (μg/24 h) | |||

| THF | 329 | 280 | 94–720 |

| 5α-THF | 49 | 290 | 152–820 |

| α-Cortol | 14 | 22 | 11–87 |

| β-Cortol | 49 | 44 | 40–302 |

| THE | 6663 | 5382 | 235–1781 |

| α-Cortolone | 738 | 640 | 61–530 |

| β-Cortolone | 1317 | 664 | 64–475 |

| Sum of glucocorticoid metabolites | 9159 | 7322 | 832–4312 |

| Diagnostic ratios | |||

| 5α-THF+THF/THE | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.7–1.3 |

| Cortols/cortolones | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.26–0.50 |

| Androgen metabolites (μg/24 h) | |||

| An | 268 | 919 | 2–254 |

| Et | 180 | 276 | 1–184 |

| DHEA | 72 | 26 | 0.5–31 |

| Sum of androgen metabolites | 520 | 1221 | 5–455 |

H6PD genetic analysis

Case 1 was compound heterozygous for a previously identified, paternally inherited c.325delC mutation resulting in a frameshift with the generation of an in-frame stop codon (p.R109AfsX3) severely truncating the H6PDH protein. We also identified a novel maternally inherited c.437C>T mutation, generating a proline to leucine missense mutation (p.P146L) in a conserved region of the H6PDH protein.

Case 2 was compound heterozygous for a c.973C>T nonsense mutation (p.Q325X) and a c.1338C>G nonsense mutation (p.Y446X) both of which generate premature stop codons that severely truncate the H6PDH protein (no parental DNA was available for typing).

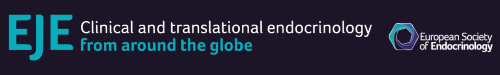

H6PDH enzyme activity assays and protein modelling

To examine the functional effects of the three novel mutations on H6PDH enzyme activity, both mutant and WT H6PDH sequences were used to transfect the HEK293 mammalian cell line. Cells over-expressing WT H6PDH had robust activity (Fig. 1A), whereas mock-transfected cells had low H6PDH activity due to endogenous levels of the enzyme. Activity in cells transfected to similar levels (as evidenced by similar mRNA expression) with the three mutant constructs was indistinguishable from mock-transfected controls (Fig. 1A), highlighting that these mutations were indeed inactivating. Western blot analyses of total microsomal proteins indicated that compared with WT, p.P146L was produced at a similar level (Fig. 1A). No H6PDH protein was detected from p.Y446X or p.Q325X as the peptide sequence used to raise the H6PDH antibody would be missing in these truncated proteins (Fig. 1A). The region containing p.P146 is not only conserved within H6PDH from a variety of species but also present in the highly related cytosolic protein, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH; Fig. 1B). In crystal structures of G6PDH, the equivalent proline residue (Pro144), together with the adjacent proline (Pro143), forms a turn close to the coenzyme NADP+ (Fig. 1B). Hydrogen bonding between Pro143 and NADP+ is known to contribute to cofactor binding (14).

Figure 1.

Molecular analysis of novel H6PD mutations. (A) H6PDH enzyme activity assays in HEK293 cells mock transfected or stably transfected with the WT and mutant cDNA constructs expressed as nmol NADPH/min per mg microsomal protein (mean±s.e.m.; n=3). Western blot analysis of microsomal proteins from HEK293-transfected cells. H6PDH protein is clearly visible in cells expressing both WT and P146L. No signal is visible for p.Y446X or p.Q325X as the peptide sequence used to raise the H6PDH antibody would be missing in these truncated proteins. Anti-calreticulin antibody was used as a loading control. (B) Protein alignments across species of both H6PDH and the related enzyme, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), indicating significant sequence conservation of the proline (P146L) residue (marked with *). Ribbon representation of the crystal structure of G6PDH (composite of two structures; PDB codes: 2BH9, 2BHL – chain A only). The glucose-6-phosphate substrate (G6P, red) and coenzyme NADP (orange) bind at adjacent sites. Another ‘structural’ NADP (pink) binds some distance away. Right-hand panel is a close-up of the coenzyme NADP+ binding region showing the proximity of the key proline residues (highlighted in green) to the bound coenzyme. Structural images produced using UCSF Chimera from the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera, supported by NIH P41 RR-01081) (19). Full colour version of this figure available via http://dx.doi.org/10.1530/EJE-12-0628.

Urinary steroid metabolome analysis and the diagnostic spectrum of ACRD/CRD

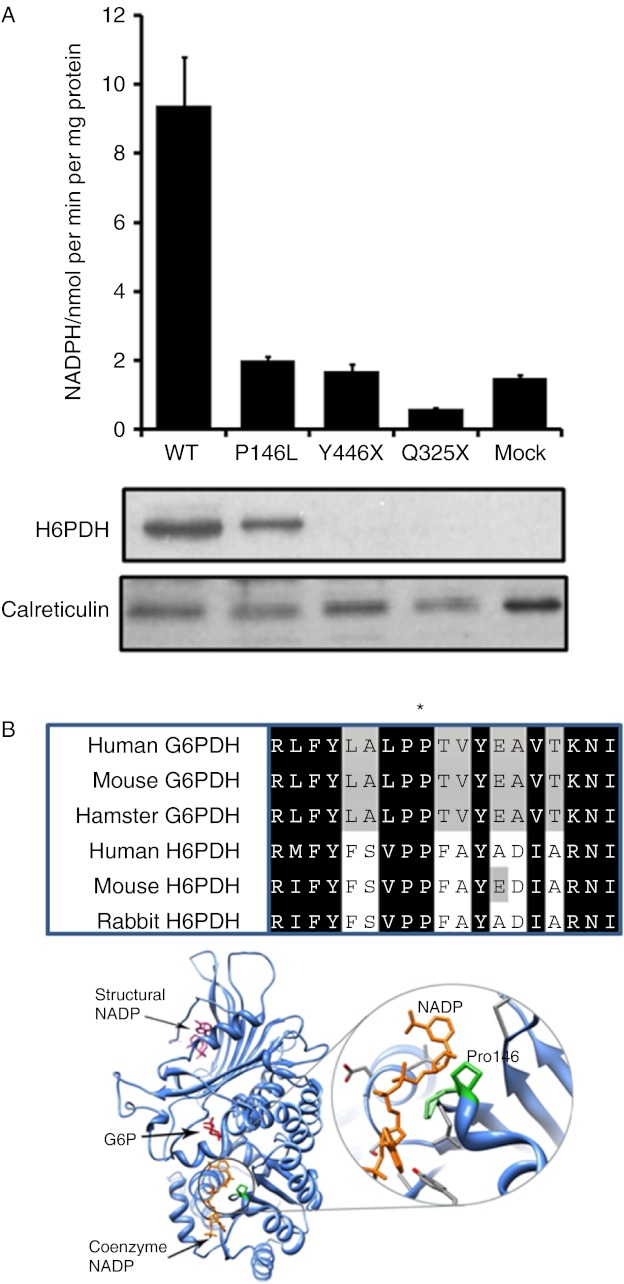

To evaluate these newly defined ACRD cases in a broader context, they were compared with the previously established ACRD and CRD cases we have investigated (4, 5) using GC/MS analysis. As our previously described CRD cases had a dominant negative mode of inheritance, we reasoned that the affected parent (in both cases the mothers) should be included in the analysis of their urine steroid metabolome; hence, we present four urine profiles consistent with CRD. To do this, we have generated a comparative output with ACRD and CRD cases plotted against normal age-matched reference ranges with box plots representing the interquartile ranges (25th–75th percentiles) and whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles respectively. Of the reference cohorts used, we plotted on a log scale diagnostic ratios, glucocorticoid and adrenal androgen metabolite concentrations and total cortisol and androgen metabolites to estimate HPA activity and adrenal output as a further means to diagnose and differentiate future cases of ACRD and CRD.

In children, there is a propensity for lower cortisol metabolite concentrations (THF, 5α-THF and cortols) and a greater deviation from the age-related normal range in cortisone metabolite concentrations (THE and the cortolones) in ACRD compared with CRD cases, with the data highlighting the need to compare these values to specific age-related reference ranges (Fig. 2A). Urinary cortisol and total cortisol metabolite values were elevated above the normal age-related reference range in ACRD cases and towards the top of the normal range in CRD cases (Fig. 2A), possibly indicating a greater degree of HPA axis activation in ACRD cases. As for adult females, there is more clear demarcation between CRD and ACRD, possibly as a result of differential lifelong enhanced HPA activity. Again, cortisol metabolites tend to be lower in ACRD cases, but ACRD cases also have clear demarcation from CRD cases in the elevated levels of cortisone metabolites. ACRD cases also have higher urinary free cortisol and a clear elevation of total cortisol metabolites compared with CRD cases, with both being elevated above normal output (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Urinary glucocorticoid metabolites defining ACRD/CRD. (A) Children. All diagnosed CRD/ACRD children (n=5; ACRD: closed circle, 6 years; closed triangle, 7 years; closed square, 4 years; CRD: open circle, 8 years; open triangle, 13 years) plotted on a log scale for a range of glucocorticoid metabolites found in urine, plotted against an age-matched reference cohort (grey box plots: age 1–7 years, n=22, 12 boys and ten girls; white box blots: age 8–14 years, n=31, 13 boys and 18 girls). (B) Adult females. All diagnosed CRD/ACRD adult females (n=5; closed symbols represent ACRD and white circles represent CRD cases) plotted on a log scale for a range of glucocorticoid metabolites found in urine, plotted against an age-matched reference cohort (age 18–63 years; n=89). Box plots represent the interquartile ranges (25th–75th percentiles), and whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles. For steroid abbreviation, please refer to Patients and methods section.

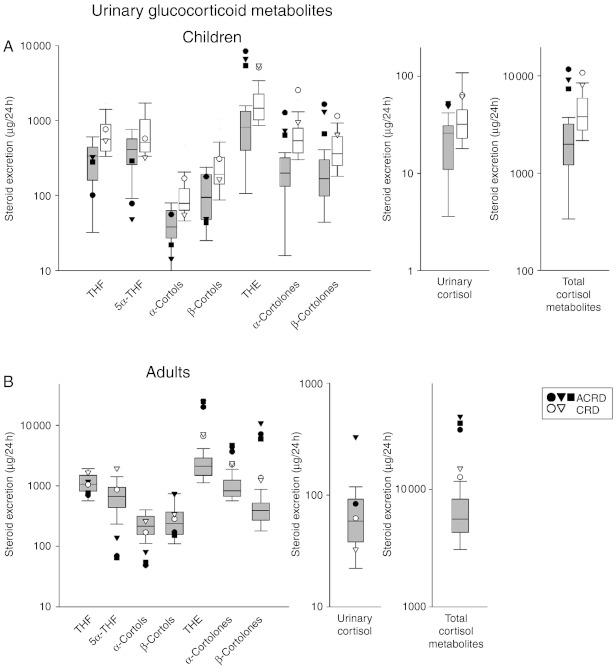

To enhance interpretation, we used diagnostic substrate to product metabolite ratios: the well-established THF+5α-THF/THE ratio and the cortol/cortolone ratio as a further confirmatory ratio. The normal range for these ratios does not differ significantly between the age-related reference range cohorts for all cases we have combined the data. For the THF+5α-THF/THE ratio, this value is invariably ≤0.1 in ACRD and for CRD ≥0.1 but ≤0.5, with the highest CRD ratio recorded still below the normal range (Fig. 3). This is in agreement within the cortol/cortolone ratio with a similar pattern being observed (Fig. 3). Together, these ratios provide confidence in diagnosing and discriminating between CRD and ACRD. The 5α-THF/THF ratio is a marker of 5α/5β-reductase activity and demonstrates that there is a preferential 5β-metabolism route in some but not all ACRD cases, but the basis for this differential activity is unknown.

Figure 3.

Urinary glucocorticoid metabolite ratios defining ACRD/CRD. All previously diagnosed CRD/ACRD patients (n=5 children, five adults where available) were plotted on a log scale for their THF+5α-THF/THE, cortols/cortolones and 5α-THF/THF ratios compared with a normal range of combined adults and children, as there is no difference in these ratios between age groups in their independent normal ranges. For all three ratios, there is a similar demarcation between ACRD (closed shapes) and CRD (open shapes) in most instances, with ACRD ratios being most divergent from the normal range. Box plots represent the interquartile ranges (25th–75th percentiles), and whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles. Each symbol represents an individual case-specific measurement, closed symbols for ACRD cases and open symbols for CRD cases. For steroid abbreviation, please refer to Patients and methods section.

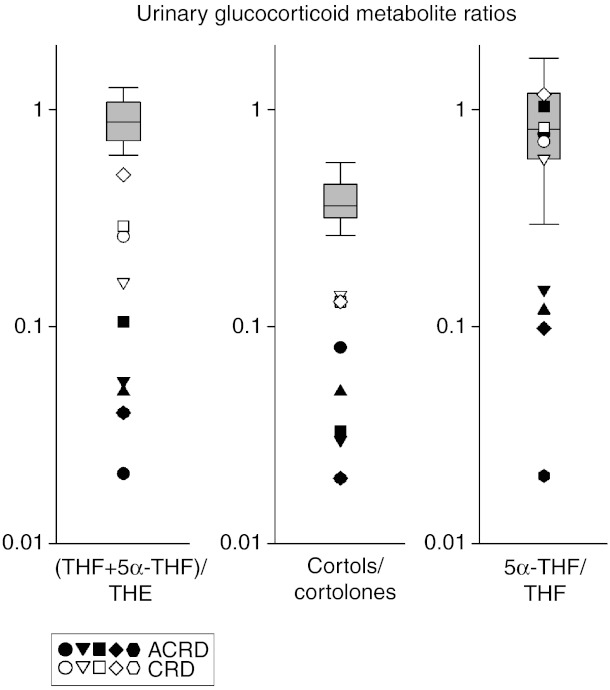

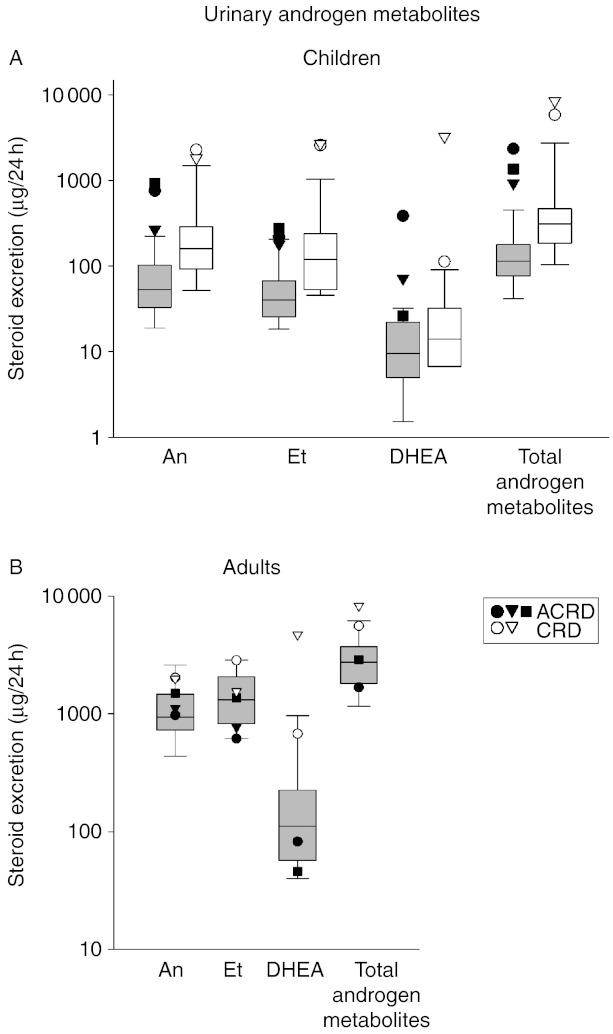

Finally, the functional consequence of reduced or abolished 11β-HSD1 activity is HPA activation as demonstrated by elevated total glucocorticoid output; therefore, the same might be anticipated for adrenal androgen output. Circulating serum androgens are elevated in all cases, so we examined the urine androgen metabolite profile also. In the urine of CRD and ACRD children, there are elevations in adrenal-derived androgens (An, Et and DHEA) above the normal range and as a result increased total androgen output, corroborating the increased total cortisol metabolite output (Fig. 4A). It does not appear that CRD and ACRD can be distinguished when compared with the degree of difference to their age-matched normal ranges, unlike the total glucocorticoid metabolites that show a greater degree of elevation above the age-matched normal range in ACRDs. No significant differences were observed between adult female cases, though there is a tendency towards the CRD cases having more pronounced androgen output with values towards the top of the normal range (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Urinary androgen metabolites defining ACRD/CRD. (A) Children. All diagnosed CRD/ACRD children (n=5; ACRD: closed circle, 6 years; closed triangle, 7 years; closed square, 4 years; CRD: open circle, 8 years; open triangle, 13 years) plotted on a log scale for a range of androgen metabolites found in urine, plotted against an age-matched reference cohort (grey box plots: age 1–7 years, n=22, 12 boys and ten girls; white box blots: age 8–14 years, n=31, 13 boys and 18 girls). (B) Adult females. All diagnosed CRD/ACRD adult females (n=5; closed symbols represent ACRD and open symbols represent CRD cases) plotted on a log scale for a range of androgen metabolites found in urine, plotted against an age-matched reference cohort (age 18–63 years; n=89). Box plots represent the interquartile ranges (25th–75th percentiles), and whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles. For steroid abbreviation, please refer to Patients and methods section.

Discussion

Here, we provide the biochemical and genetic basis for two novel cases of ACRD due to H6PDH deficiency in girls presenting with premature adrenarche at age 4 and 7 years. We highlight the diagnostic value of urinary GC/MS in this condition, as neither CRD nor ACRD can be diagnosed by conventional approaches analysing standard plasma steroid hormones. Furthermore, an extended comparison of the urinary steroid profiles of all available ACRD/CRD cases emphasises the urinary biomarkers best able to differentiate these genetic disorders when considering the differential diagnosis of cases of premature adrenarche and androgen excess disorders in childhood and adolescence.

In these novel cases presenting with premature adrenarche, more commonly diagnosed conditions such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) were excluded. On this basis, 24-h urine collections were used to assess the urinary steroid profile, upon which the genetic testing was initiated. This led to the identification of three novel mutations in the H6PD gene. Case 1 was a compound heterozygote for a previously described cytosine insertion into exon 2 causing a frameshift and nonsense codon severely truncating the H6PDH protein, and a novel p.P146L missense mutation, which we have shown through in silico three-dimensional protein modelling to potentially impact upon cofactor binding, thus rendering NADPH production to be abolished. Case 2 was a compound heterozygote for nonsense mutations p.Q325X and p.Y446X, both of which severely truncate the H6PDH protein ablating function. Together, these three novel mutations bring the total described mutations leading to loss of H6PDH function to eight.

We have previously described the adult presentation of H6PDH deficiency in three females (4). In these individuals, lifetime loss of 11β-HSD1-mediated clearance of cortisol to cortisone and chronic HPA axis activation has led to adrenal hyperplasia, exaggerated adrenal androgen production and circulating hyperandrogenemia resulting in a PCOS-like phenotype (1, 2, 3). Adults presenting with ACRD may have had a premature adrenarche in their childhood, which did not come to clinical attention. We have also recently identified two young males (age 8 and 11 years) presenting with premature pubarche and adrenal androgen excess due to dominant negative mutations in the HSD11B1 gene, resulting in deficiency of 11β-HSD1 oxo-reductase activity (5). Given the mode of inheritance in these two CRD cases, we have also included the mothers, also carrying the HSD11B1 mutations, in the genetically defined CRD cohort. We have now reported a total of ten cases in which we can describe a continuum of clinical and biochemical presentation, three adults and three children with ACRD, and two adults and two children with CRD.

Urinary steroid metabolite analysis is an important tool for identifying steroid-related disorders and we have extended this to now include the identification of CRD/ACRD patients (10, 15, 16, 17). We show markers that define not only the range in which ACRD and CRD exists but also the difference between them. The biomarker panel offers insight into the levels of a range of urinary metabolites of steroid hormones that are decreased (the cortisol derivatives, e.g. cortols) or increased (the cortisone derivatives, e.g. cortolones, and the urinary androgen metabolites An, Et and DHEA). In addition, urinary steroid profiling offers a means to assess HPA axis activity and adrenal output. The THF+5α-THF/THE and cortols/cortolones ratios are useful indicators of in vivo 11β-HSD1 activity highlighting deficient 11β-HSD1 activity. The absolute values of the cortisone metabolites THE and cortolones are robust markers of the differences between ACRD and CRD being elevated to a greater extent in ACRD compared with CRD children with respect to the upper limits of the age-matched reference ranges. In adults, the THE and the cortolone values are markedly elevated in ACRD compared with CRD cases, offering useful insight. The THF+5α-THF/THE and cortol/cortolone ratios offer the clearest distinction between ACRD and CRD, with a value of <0.1 in the former ratio indicating ACRD. We also observed that some ACRD cases have a low value for the 5α-THF/THF ratio, indicating enhanced 5β-reductase activity, or concomitant deficiency in 5α-reductase activity, though the basis for this alteration in activity is unknown. Interestingly, the opposite pattern, i.e. an increased 5α-THF/THF ratio, with 5β-reductase deficiency is observed in patients with apparent mineralocorticoid excess secondary to mutations in 11β-HSD2 (18). It appears that 5α-reductase and 5β-reductase activities are intricately linked to the cortisol–cortisone set point. On this basis, we believe this relatively simple diagnostic tool can define a case of CRD or ACRD offering a differential diagnosis for premature adrenarche in children, or PCOS in adult females. This could now be considered as an additional resource when assessing patients with unexplained hyperandrogenism.

Medical management of CRD and ACRD will vary. Hydrocortisone treatment at an optimised dose regimen may be sufficient to suppress HPA activity and reduce adrenal androgen production in cases of CRD. However, in cases of ACRD in which HPA axis activation is more florid, increased activity of the 11β-HSD1 dehydrogenase reaction, converting cortisol to cortisone, might be expected to more rapidly inactivate hydrocortisone, thereby reducing its potency. In these cases, it may be more appropriate to administer a long-acting synthetic glucocorticoid such as prednisolone or dexamethasone, with the latter not being metabolised by 11β-HSD1 at all. Where used in published cases of ACRD, dexamethasone has effectively suppressed hyperandrogenism and led to reversal of clinical phenotypes (1, 3, 11). In an analogous fashion to treating congenital adrenal hyperplasia secondary to biosynthetic defects, the risks of a negative impact on metabolic parameters will need to be considered carefully taking into account sex and age of the individual patient and the observed degree of HPA activation. In the paediatric setting, this is especially important when balancing the growth suppressive effects of glucocorticoids over treatment against the potentially detrimental consequences of ongoing hyperandrogenism.

In summary, urinary steroid profiling by GC/MS of unresolved cases of adrenal hyperandrogenism in patients with premature adrenarche, pubarche or PCOS should form the ‘gold standard’ in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of ACRD/CRD and allow further stratification to improve patient treatment and outcome.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported by a BBSRC David Philips fellowship to G G Lavery (BB/G023468/1), a Welcome Trust programme grant to P M Stewart and E A Walker (082809) and MRC Research Training Fellowships to M Sherlock (G0601429) and J Idkowiak (G1001964).

References

- Biason-Lauber A, Suter SL, Shackleton CH, Zachmann M. Apparent cortisone reductase deficiency: a rare cause of hyperandrogenemia and hypercortisolism. Hormone Research. 2000;53:260–266. doi: 10.1159/000023577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper N, Walker EA, Bujalska IJ, Tomlinson JW, Chalder SM, Arlt W, Lavery GG, Bedendo O, Ray DW, Laing I, et al. Mutations in the genes encoding 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase interact to cause cortisone reductase deficiency. Nature Genetics. 2003;34:434–439. doi: 10.1038/ng1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson A, Wallace AM, Andrew R, Nunez BS, Walker BR, Fraser R, White PC, Connell JM. Apparent cortisone reductase deficiency: a functional defect in 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84:3570–3574. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.10.3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery GG, Walker EA, Tiganescu A, Ride JP, Shackleton CH, Tomlinson JW, Connell JM, Ray DW, Biason-Lauber A, Malunowicz EM, et al. Steroid biomarkers and genetic studies reveal inactivating mutations in hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in patients with cortisone reductase deficiency. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93:3827–3832. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson AJ, Walker EA, Lavery GG, Bujalska IJ, Hughes B, Arlt W, Stewart PM, Ride JP. Cortisone-reductase deficiency associated with heterozygous mutations in 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1. PNAS. 2011;108:4111–4116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014934108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malunowicz EM, Romer TE, Urban M, Bossowski A. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 deficiency (‘apparent cortisone reductase deficiency’) in a 6-year-old boy. Hormone Research. 2003;59:205–210. doi: 10.1159/000069326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordenstrom A, Marcus C, Axelson M, Wedell A, Ritzen EM. Failure of cortisone acetate treatment in congenital adrenal hyperplasia because of defective 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase reductase activity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;84:1210–1213. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.4.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipou G, Higgins BA. A new defect in the peripheral conversion of cortisone to cortisol. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 1985;22:435–436. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(85)90451-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipov G, Palermo M, Shackleton CH. Apparent cortisone reductase deficiency: a unique form of hypercortisolism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:3855–3860. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.11.3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idkowiak J, Lavery GG, Dhir V, Barrett TG, Stewart PM, Krone N, Arlt W. Premature adrenarche: novel lessons from early onset androgen excess. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2011;165:189–207. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson JW, Walker EA, Bujalska IJ, Draper N, Lavery GG, Cooper MS, Hewison M, Stewart PM. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1: a tissue-specific regulator of glucocorticoid response. Endocrine Reviews. 2004;25:831–866. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery GG, Walker EA, Draper N, Jeyasuria P, Marcos J, Shackleton CH, Parker KL, White PC, Stewart PM. Hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase knock-out mice lack 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1-mediated glucocorticoid generation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:6546–6551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semjonous NM, Sherlock M, Jeyasuria P, Parker KL, Walker EA, Stewart PM, Lavery GG. Hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase contributes to skeletal muscle homeostasis independent of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1. Endocrinology. 2011;152:93–102. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaka M, Gover S, Vandeputte-Rutten L, Au SW, Lam VM, Adams MJ. Structural studies of glucose-6-phosphate and NADP+ binding to human glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Acta Crystallographica. Section D, Biological Crystallography. 2005;61(Pt 5):495–504. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905002350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt W, Biehl M, Taylor AE, Hahner S, Libé R, Hughes BA, Schneider P, Smith DJ, Stiekema H, Krone N, et al. Urine steroid metabolomics as a biomarker tool for detecting malignancy in adrenal tumors. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:3775–3784. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone N, Hughes BA, Lavery GG, Stewart PM, Arlt W, Shackleton CH. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) remains a pre-eminent discovery tool in clinical steroid investigations even in the era of fast liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2010;121:496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone N, Reisch N, Idkowiak J, Dhir V, Ivison HE, Hughes BA, Rose IT, O'Neil DM, Vijzelaar R, Smith MJ, et al. Genotype–phenotype analysis in congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to P450 oxidoreductase deficiency. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:E257–E267. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monder C, Shackleton CH, Bradlow HL, New MI, Stoner E, Iohan F, Lakshmi V. The syndrome of apparent mineralocorticoid excess: its association with 11β-dehydrogenase and 5β-reductase deficiency and some consequences for corticosteroid metabolism. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1986;63:550–557. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-3-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera – a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]