Abstract

There are eight subtypes of P2Y receptors (P2YRs) that are activated, and in some cases inhibited, by a range of extracellular nucleotides. These nucleotides are ubiquitous, but their extracellular concentration can rise dramatically in response to hypoxia, ischemia, or mechanical stress, injury, and release through channels and from vesicles. Two subclasses of P2YRs were defined based on clustering of sequences, second messengers, and receptor sequence analysis. The numbering system for P2YR subtypes is discontinuous; i.e., P2Y1–14Rs have been defined, but six of the intermediate-numbered cloned receptor sequences (e.g., P2y3, P2y5, P2y7–10) are not functional mammalian nucleotide receptors. Of these two clusters, the P2Y12–14 subtypes couple via Gαi to inhibit adenylate cyclase, while the remaining subtypes couple through Gαq to activate phospholipase C. Collectively, the P2YRs respond to both purine and pyrimidine nucleotides, in the form of 5′-mono- and dinucleotides and nucleoside-5′-diphosphosugars. In recent years, the medicinal chemistry of P2Y receptors has advanced significantly, to provide selective agonists and antagonists for many but not all of the subtypes. Ligand design has been aided by insights from structural probing using molecular modelling and mutagenesis. Currently, the molecular modelling of the receptors is effectively based on the X-ray structure of the CXCR4 receptor, which is the closest to the P2Y receptors among all the currently crystallized receptors in terms of sequence similarity. It is now a challenge to develop novel and selective P2YR ligands for disease treatment (although antagonists of the P2Y12R are already widely used as antithrombotics).

The P2Y receptors (P2YRs) are a family of eight G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that belong to the rhodopsin-like branch GPCRs, also known as class A or Family 1 GPCRs.1,2 There are activated, and in some cases inhibited, by a range of naturally occurring extracellular nucleotides. These nucleotides are ubiquitous, but their extracellular concentration can rise dramatically in response to hypoxia, ischemia, or mechanical stress, injury, and release through channels and from vesicles. The P2Y family can be further divided into a subfamily of five P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, and P2Y11Rs (“P2Y1-like”) that stimulate phospholipase C (PLC) through Gq protein and a second subfamily of P2Y12, P2Y13, and P2Y14Rs (“P2Y12-like”) that inhibit adenylate cyclase through Gi protein (Table 1).3 Other effector pathways have been documented, such as coupling of the P2Y11R to Gs as well as to Gq in some cells to induce stimulation of cyclic AMP production.4

Table 1.

Properties P2YRs and key agonist antagonist ligands.

| Group | Subtype, gene symbol | G protein | Ligand agonist/ antagonist | pEC50 | Other interactions, Subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| P2Y1-like | P2Y1, P2RY1 | Gq | MRS2365 8 | 9.40 | selective |

| 2-MeSADP 3 | 8.18 | P2Y1, P2Y12 | |||

| ADPβS 6 | 5.62 | P2Y1, P2Y12 | |||

| ADP 1 | 5.09 | P2Y1, P2Y12 | |||

|

|

|||||

| MRS2500 31d | 9.02 | selective | |||

| MRS2279 30d | 8.10 | selective | |||

| MRS2179 29d | 6.48 | selective | |||

|

| |||||

| P2Y2, P2RY2 | Gq, Gi | UTP 12 | 8.10 | P2Y4 | |

| MRS2698 20b | 8.10 | selective | |||

| ATP 2 | 7.07 | P2Y4,11 + others | |||

| PSB1114 17 | 6.87 | selective | |||

| MRS2768 16 | 5.72 | selective | |||

|

|

|||||

| PSB-716 40 | 5.01 | ||||

|

| |||||

| P2Y4, P2RY4 | Gq, Gi | MRS4062 21 | 7.64 | selective | |

| UTP 12 | 6.26 | P2Y4 | |||

| GTP 5 | 5.18 | nonselective | |||

|

|

|||||

| ATP 2a | 6.15 | P2Y2,11 + others | |||

|

| |||||

| P2Y6, P2RY6 | Gq | MRS2957 19b | 7.92 | selective | |

| 5-iodo-UDP 23 | 7.83 | selective | |||

| PSB-0474 22 | 7.15 | selective | |||

|

|

|||||

| MRS2578 49 [noncompetitive] | 7.43 | selective | |||

|

| |||||

| P2Y11, P2RY11 | Gq, Gs | NF546 43c | 6.27 | ||

| ATP 2 | 4.77 | P2Y2,4 + others | |||

| ATPγS 7 | 4.62 | nonselective | |||

|

|

|||||

| NF157 42 | 7.35 | ||||

| NF340 44 | 7.14 | selective | |||

|

| |||||

| P2Y12-like | P2Y12, P2RY12 | Gi | 2-MeSADP 3 | 8.3 | P2Y1,13 |

| ADP 1d | 7.22 | P2Y1,13 | |||

|

|

|||||

| PSB-0739 39 | 9.8 | selective | |||

| AR-C69931MX 34 | 9.40 | P2Y11 | |||

| AZ11931285 36d | ~9 | selective | |||

| AR-C67085 33bd | 8.3 | P2Y11 | |||

| AZD6140 37 | 7.90 | selective | |||

|

| |||||

| P2Y13,b P2RY13 | Gi | ADP 1 | 7.94 | P2Y1,12 | |

| 2-MeSADP 3 | 7.72 | P2Y1,12 | |||

|

|

|||||

| MRS2211 48 | 5.97 | selective | |||

|

| |||||

| P2Y14, P2RY14 | Gi | MRS2905 26 | 8.70 | selective | |

| MRS2690 29 | 7.31 | selective | |||

| MRS2802 25 | 7.20 | selective | |||

| UDP 11d | 6.80 | P2Y6 | |||

| UDP-glucose 27 | 6.45 | P2Y2 | |||

|

|

|||||

| PPTN 56 | 8.7 | selective | |||

At the human P2Y4 receptor, but ATP acts as an agonist at the rat or mouse P2Y4 receptor.

NF546 activates the P2Y11R, although it belongs to a structural class of antagonists.

Used as a radioligand, when labelled with [3H], [32P], [33P] or [125I], as appropriate.]

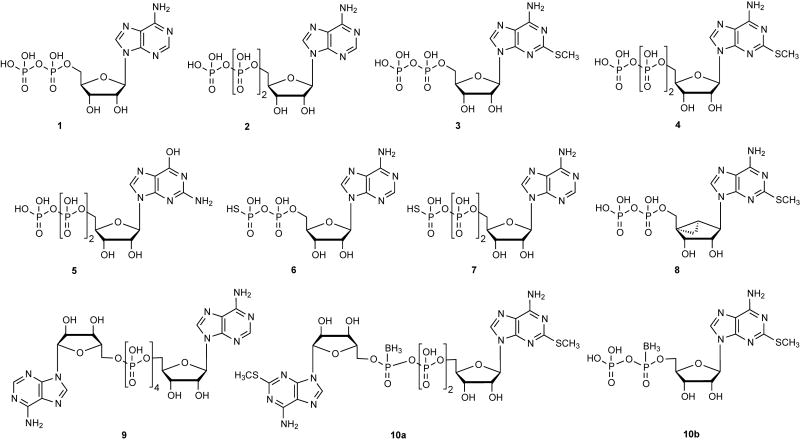

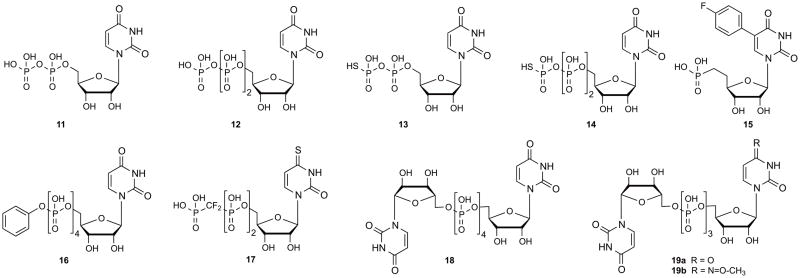

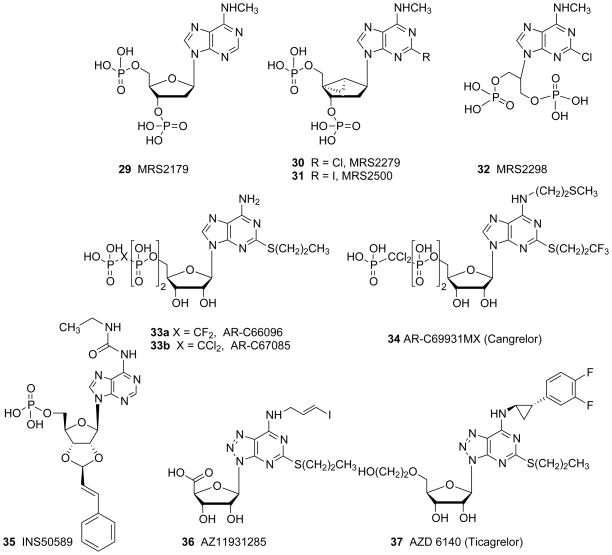

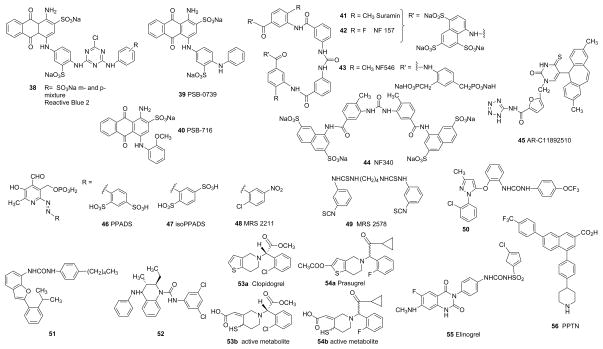

There are species differences in the occurrence, function and ligand preference of the P2YRs, e.g. mice lack a P2Y11R gene in their genome.5 The structures of representative ligands used as tools for defining the role of the P2YRs are shown in Figures 1 (agonists) and 2 (antagonists). The principal native agonists for these receptors are: ADP 1 for P2Y1, P2Y12, and P2Y13; ATP 2 for P2Y2, P2Y4 (rat, but not human) and P2Y11; UDP 11 for P2Y6 and P2Y14; UTP 12 for P2Y2 and P2Y4; UDP-glucose 27 and other UDP-sugars for P2Y14. In some cases, the same nucleotide that activates one P2YR subtype may antagonize another subtype, for example ATP and other 5′-triphosphate analogues act as antagonists at the P2Y12R in platelets.6

Figure 1.

Nonselective and selective P2YR agonists derived from nucleotides. A. Purine derivatives. B. and C. Pyrimidine derivatives. The P2Y potencies of ligands selected from these figures are provided in Table 1.

STRUCTURAL CHARACTERIZATION OF P2Y RECEPTORS: MOLECULAR MODELING AND MUTAGENESIS

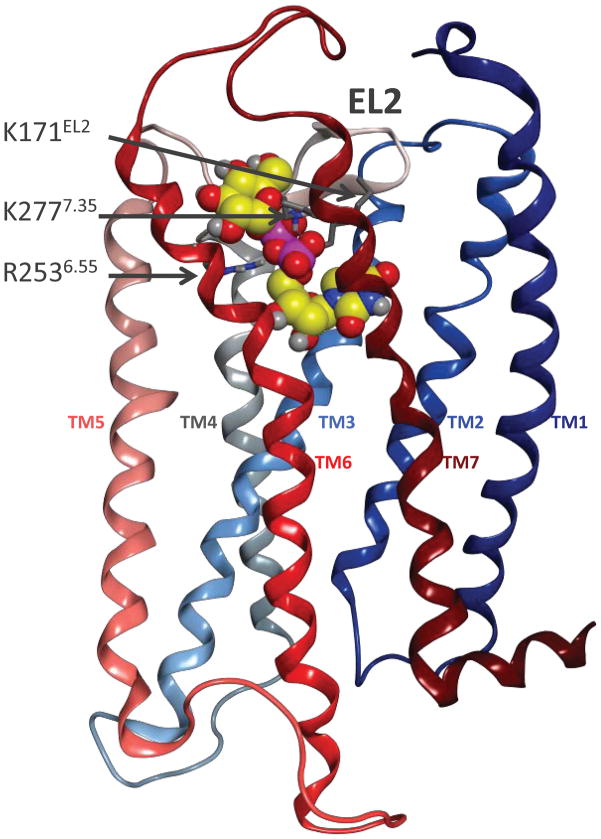

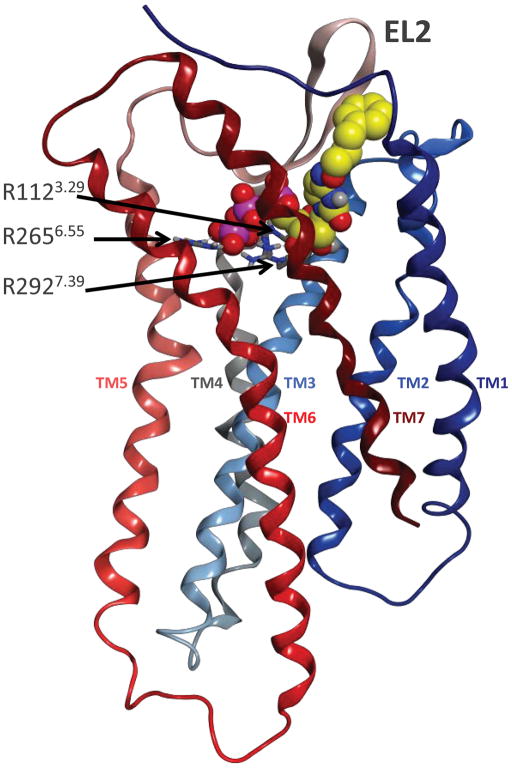

As for other G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), the P2YRs display the characteristic structural motif of a single polypeptide with seven α-helical transmembrane domains (TMs).3 The ligand binding site is thought to be primarily within a cleft surrounded by the TM domains. However, there is evidence that the extracellular loops (ELs) are also involved in coordinating the nucleotide ligands. This is especially applicable to EL2, which often extends into the binding cleft. On the cytosolic side, the three intracellular loops (ILs) and the C-terminus are involved to varying degrees in signalling functions within proximity of the docked G protein. None of the P2YRs are solved structurally using X-ray crystallography. However, extensive site-directed mutagenesis of residues that are predicted to coordinate the ligands,7–18 structure activity studies of ligand analogues,19–30 and molecular modelling7,9.31–34 have provided insight into molecular recognition of the P2YRs.

Molecular modeling of the P2YRs and ligand docking have identified putative recognition functions for some of the conserved TM residues. Early in this progression, positively charged residues were predicted to coordinate the negatively charged phosphate moieties that are a required feature of known P2YR agonists.1,3 The division of the P2YRs into two subfamilies (P2Y1R-like and P2Y12R-like) corresponds not only to second messenger pathways, but also to sequence alignments, phylogenetic analysis, and the identification of residues with key functions for each of the subtypes. The sequence identity between the P2Y1R-like and P2Y12R-like subfamilies is only approximately 20%. Therefore, the modelling and mode of ligand docking must be established independently for each of the subfamilies. The sequence identity within each subfamily is higher, typically in the 40–50% range.

Specific residues within the TM domains of the P2Y1R appear to be involved in ligand recognition or receptor functionality according to mutagenesis data and can be subdivided in two categories. Positively charged residues (using the numbering convention of Ballesteros and Weinstein36) are likely implicated in the coordination of the phosphate moiety of the ligands, namely R1283.29, K2806.55, and R3107.39. Neutral residues, namely Y2736.48, H2776.52, Q3077.36 and Ser3147.43 were also essential or modulatory for the action of nucleotides at the P2Y1R.35 According to mutagenesis data, charged residues of the EL domains were also found to be involved in ligand recognition or receptor functionality. Specifically, in the P2Y1R mutagenesis of D204, E209, and R287 interfered with activation by nucleotides, while in the P2Y2R, similar effects were found for R177, R180, and R272.12,13 Furthermore, P2Y1R mutagenesis has demonstrated the presence of two putative disulfide bridges necessary for proper activation: one between TM3 and EL2 that is found in most class A GPCRs, and a second less common disulfide bridge formed between the N-terminus and the junction between EL3 and TM7.13 Beyond the P2Y1R, the following residues within the TMs domain were found to be involved in ligand recognition for other members of the first subfamily: Y1183.37 and Y2686.58 for the P2Y2R12; Y2616.48, R2686.55, and R3077.39 for the P2Y11R.10 Moreover, within the second subfamily the positively charged residues R2566.55 and K2807.35, and neutral residues, H2536.48 and Y2596.52, were found to be involved in ligand recognition for the P2Y12R.14

P2YR molecular modeling, initially based on highly speculative grounds and using templates of low resolution and little sequence homology7,31, has progressed dramatically in the past 20 years. The accuracy of the modelling appears to have improved as judged by the ability to correlate features of the docked ligands with the receptor structure. Various GPCR structures have been used as templates for P2YR homology modeling. Initially, the high resolution structure of bovine rhodopsin revealed in 2000 was used to build models,37 and homology modeling has been applied to all of the P2YRs at various times.3 The first P2Y subtype to which extensive molecular modelling was applied in conjunction with site-directed mutagenesis was the P2Y1R. The putative nucleotide binding pocket of this subtype was proposed to be located within the upper third (from the extracellular surface) of TMs 3, 6, and 7. The positively charged residues occurring in each of these TMs of the P2Y1R, which were conserved among the P2Y1-like receptors, clustered around the putative position of the negatively charged phosphate group of the native agonist ADP. The β2 adrenergic receptor structure38 was used as an improved modelling template for the P2YR family, but that was eventually superseded. Recently, an alternative template was shown to be more consistent with the characteristics of the P2YRs with respect to modelling.24,34 X-ray structures of the antagonist-bound form of the human CXCR4, a peptide receptor, were reported in 2010 by Stevens and coworkers.39 The sequence identity of the human P2Y12R and the CXCR4 chemokine receptor is 22% overall and 26% for the TM domains. Additional structural features of CXCR4 were shared with P2YRs, making the crystal structure of CXCR4 a more suitable modeling template for both subfamilies of the P2YRs over other available GPCR crystal structures.34

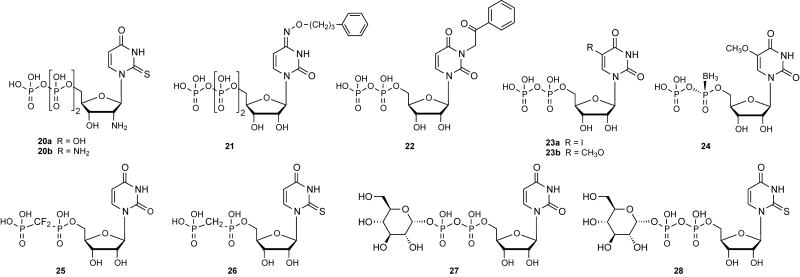

The impact of using different templates for P2YR modeling is illustrated with two cases: the P2Y4R and the P2Y14R (Figure 3). One of the first models of the P2Y14R in complex with the natural agonist UDP-glucose is shown in Figure 3A.3 The homology model was constructed on the basis of the crystal structure of rhodopsin, which at the time was the only GPCR with a crystallographically solved structure.37 Consequently, EL2 overlays and occludes the extracellular opening of the binding cavity, as in rhodopsin. This situation most likely does not reflect the actual conformation of the loop in the P2Y receptors as it would impede the access of nucleotides to the binding cavity. The greater difficulty of modeling loop regions in comparison to the TMs has been a long standing problem in GPCR modeling, and is not particular to the P2YRs.

Figure 3.

A. Previous model of the P2Y14R, based on the structures of rhodopsin, in complex with the natural agonist UDP-glucose 27. Three cationic residues, shown in sticks representation with gray carbons, coordinate the phosphate moieties of the ligand, shown in space filling representation with yellow carbons. The backbone of the receptor is schematically rendered as a ribbon colored with a continuum spectrum going from blue, at the N-terminus, to dark red, at the C-terminus. B. Recent model of the P2Y4R based on the structures of the CXCR4 receptor, in complex with a synthetic agonist, MRS4062 21. Three cationic residues, shown in sticks representation with gray carbons, coordinate the phosphate moieties of the ligand, shown in space filling representation with yellow carbons. The backbone of the receptor is schematically rendered as a ribbon colored with a continuum spectrum going from blue, at the N-terminus, to dark red, at the C-terminus.

Three cationic residues, i.e. K171EL2, R2536.55, and K2777.35, coordinate the phosphate moieties of the ligands in the model. These residues are conserved as cationic residues in all the subtypes belonging to the subfamily of the Gi coupled P2YRs, which encompasses the P2Y12, P2Y13 and P2Y14 subtypes.3 Figure 3B shows a recent model of the P2Y4R in complex with a synthetic agonist, namely a CTP derivative substituted with a phenylalkoxyimino group at position 4 of the pyrimidine ring, MRS4062 21.24 In this case, the homology model was constructed on the basis of the crystal structure of CXCR4.39 Moreover, the CXCR4 receptor shares a disulfide bridge with the P2YRs to connect the N-terminus with the junction of EL3 and TM7. The EL2 is solvent exposed and leaves ample room for the nucleotides to diffuse into and out of the receptor. Also in this case, three cationic residues, i.e. R1123.29, R2656.55, and R2927.39, coordinate the phosphate moieties of the ligands in the model. These residues are conserved as cationic residues in all the subtypes belonging to the P2Y1-like subfamily of the Gq-coupled P2YRs, which encompasses the P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6 and P2Y11 subtypes,3 and are thought to coordinate the phosphate moiety in each case.

CHEMICAL PROBES FOR STUDYING P2Y RECEPTORS

There are inherent difficulties in the medicinal chemistry of P2YRs. Nucleotide analogues are difficult to synthesize in reproducible yield, and purification and characterization are more complicated than for many other classes of small molecule ligands of GPCRs. Furthermore, in pharmacological studies, especially in vivo, interconversion of nucleotides by ectonucleotidases and other enzymes is a serious complication.41 Endogenous nucleotides that are produced by all cells in culture often complicate the interpretation. Efforts to introduce chemical modifications that will stabilize the compounds also may reduce their potency at the P2YRs. Despite these limitations, there are now selective agonist and antagonist ligands for many but not all of the P2YRs (Table 1), and this effort has accelerated in recent years. Selective nucleotide agonists have been reported for P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6 and P2Y14 subtypes, and selective nucleotide antagonists are now known for P2Y1 and P2Y12 subtypes. Moreover, the identification of novel chemotypes to antagonize various P2Y receptors is progressing. For example, the screening of chemically diverse libraries and the use of in silico screening to greatly narrow the list of candidates have had some success in finding atypical antagonists for P2YRs.

A summary of many of the most useful agonists and antagonists at each of the P2Y subtypes is provided below (structures in Figures 1 and 2). It is now a challenge to develop novel P2YR ligands for disease treatment, in addition to the widespread use of antagonists of the P2Y12R as antithrombotics42. This requires overcoming various complicating factors such as the inherent instability and lack of bioavailability of nucleotide derivatives. Also, in vivo results emphasize the widespread occurrence of these receptors in the body, with multiple effects, both positive and detrimental, associated with the activation of each subtype. Nevertheless, promising results suggest the possible use of such agents in endocrine, gastrointestinal, inflammatory, cardiovascular, ischemic and neurological diseases.

Figure 2.

Nonselective and selective P2YR antagonists derived either from: A. nucleotides and nucleosides, or B. nonnucleotide derivatives. The P2Y potencies of ligands selected from these figures are provided in Table 1.

P2Y1R

C2-Alkylthio (and arylalkylthio) modifications of adenine nucleotides are often well-tolerated at the P2Y1R. The endogenous nucleotide ADP 1 and its monosubstituted more potent derivative 2-MeSADP 3 are full agonists at the P2Y1R. However, they are nonselective due to activation of the P2Y12 and P2Y13Rs.43 The corresponding 5′-triphosphate derivatives, i.e. ATP 2 and 2-MeSATP 4 are reported to activate the P2Y1R, but in some models demonstrate lower efficacy.1

The N6 position of adenine nucleotides that act as P2Y1R ligands can be substituted only with small alkyl groups, with the order of potency Me > Et ≫ Pr. N6-Arylalkyl analogues are inactive at the P2Y1R. Thus, the N6 group occupies a small hydrophobic pocket in the binding site. The ribose and phosphate moieties have also been extensively modified in studies of P2Y1R SAR. Thiophosphate modifications, which introduce a new chiral center if present in a nonterminal phosphate moiety, have been useful in SAR studies and increase the biological stability, e.g. ADPβS 6 is a potent P2Y1R agonist. One result of this effort was the ability to effectively convert potent P2Y1R agonists into potent antagonists. The seminal discovery by Boyer and Harden and colleagues that 3′,5′-bisphosphate derivatives of adenosine tend to antagonize the P2Y1R, made the introduction of many nucleotide antagonists of this receptor possible.44 This led to later generations of more potent antagonists of the P2Y1R that display no residual efficacy at the receptor, such as MRS2179 29, which is used widely as a pharmacological probe.

The ribose moiety of nucleotide derivatives in nature freely changes conformation, and these conformations have been described mathematically as a “pseudorotational cycle”.40 Conformational scrutiny of the ribose moiety has facilitated the introduction of more potent and selective ligands, both nucleotide agonists and antagonists of the P2Y1R. Potent antagonists, i.e. 2-iodo derivative MRS2500 31 and its 2-chloro analogue MRS2279 30, contain a rigid bicyclic ribose substitution, i.e. a bicycle[3.1.0]hexane, that maintain a conformation of the ribose-like ring that is favored at the P2Y1R.45 Therefore, the entropic barrier for the ligand to bind to the receptor is diminished resulting in a gain in affinity. This type of modification is termed North (N)-methanocarba, because it maintains a (N)-envelope conformation. The introduction of potent antagonists of the P2Y1R has led to exploration of such compounds as antithrombotic agents.

While introducing rigidity to the ribose-like moiety is capable of greatly enhancing the P2Y1R potency, the application of greater flexibility has also been explored. Certain acyclic nucleotide derivatives (bisphosphates and bisphosphonates) have found application as P2Y1R antagonists of moderate potency, but no P2Y1R agonists were discovered in that series. An example of one such acyclic antagonist is a symmetric bisphosphate MRS 2298 32.45

Chemical diversity was extensively explored in the search for P2Y1R antagonists. A representative heterocyclic compound discovered through optimization of a high throughput screening hit was a substituted 1-phenyl-3-methyl pyrazol-5-one 50, was found to be an orally-bioavailable antagonist of the P2Y1R with a Ki of 90 nM.27 Other novel antagonists of the P2Y1R have been reported.65–68

Also in the agonist series, the North (N)-methanocarba analog of 2-MeSADP, i.e. MRS 2365 8, selectively activates the P2Y1R with great selectivity over other ADP-preferring subtypes, i.e. P2Y12 and P2Y13Rs.43 A further benefit of the (N)-methanocarba modification is that the 5′-phosphate esters is more stable toward the hydrolytic action of 5′-nucleotidase (CD73). Dinucleoside triphosphates and tetraphosphates tend to activate the P2Y1R and display greater stability than the corresponding mononucleotide analogues. A means of further stabilizing the phosphate linkage is the introduction of borano analogues of the phosphate, such as in the dinucleotides that act as P2Y1R agonists, e.g. boronate-containing diadenosine triphosphate derivative 10 introduced by Fischer and co-workers, are being explored for application to Type 2 diabetes.25

P2Y2R

UTP 4 as a native P2YR agonist does not distinguish between P2Y2R and P2Y4R. ATP 2 is a second endogenous agonist of the P2Y2R, and its SAR at this receptor is much less explored than UTP. UTPγS 14 and 2-thioUTP 20a are potent agonists of the P2Y2R. A β,γ-difluoromethylene derivative of 4-thio-UTP PSB1114 17 is ~60-fold selective for the P2Y2R.30 A 2′-amino derivative MRS 2698 20b was shown to be 300-fold selective for the P2Y2R in comparison to the P2Y4R.19

Dinucleoside tetraphosphates with either uracil or mixed uracil/adenine nucleobases activate the P2Y2R and display enhanced stability in pharmacological preparations. Several such derivatives have been explored for therapeutics. For example, INS 365 (Diquafosol) 18 is used for treating dry eye disease in Japan by virtue of its action as a moderately potent P2Y2R agonist, but it is nonselective in comparison to P2Y4R.46,47 A simplified analogue similar to the dinucleotide series, MRS 2768 16 (uridine tetraphosphate δ-phenyl ester) is somewhat selective for the P2Y2R, but achieves only moderate potency.48

A phosphonate analogue of 5-aryl UMP, SVP333 15, acts as a partial agonist of the P2Y2R, but it is not competitive with other agonists and has therefore been described as an allosteric agonist.49 Compound 15 displayed an EC50 of 400 nM and reached a maximal efficacy of 43% of full agonist. The compound is more stable than other P2Y2R agonists, not being subject to cleavage by nucleotidases. It is also unusual that a monophosphate equivalent interacts potently with a P2YR.

A uracil nonnucleotide derivative AR-C11892510 45 was reported in abstract form to be a P2Y2R antagonist.1 Suramin 38 and Reactive blue 2 41, discovered early as P2 antagonists, have been chemically modified to increase receptor subtype selectivity. One such simplified derivative that maintains potency at the P2Y2R is PSB-716 40.50

P2Y4R

UTP 4 activates this receptor universally, but the action of ATP 2 at the P2Y4R is species-dependent, i.e. acting as an antagonist at the human P2Y4R and an agonist at the rat P2Y4R. It is useful to note that GTP activates this receptor with only one order of magnitude less potency than UTP. A hydrophobic pocket around the uracil 4 position was identified by SAR studies, and modifications or alkyl extensions at this site alter the P2Y2/P2Y4R selectivity of UTP analogues.24 For example, an N4-phenylpropyloxyimino derivative of CTP, MRS 4062 21, is a P2Y4R agonist that ass ~30-fold selectivity in comparison to both P2Y2R and P2Y6R. P2Y4R agonists might prove useful in treating chronic constipation by inducing chloride and water secretion in the intestinal epithelia.64

P2Y6R

UDP 3 was previously thought to be a native agonist exclusively of the P2Y6R, but it also activates the P2Y14R at similar concentrations.51 Modifications of UDP that favor the P2Y6R have resulted in UDPβS 13, 3-phenacyl UDP (PSB 0474) 22, 5-iodo-UDP (MRS 2693) 23 and 5-methoxy-UDP 24.23,29,54 Furthermore, uracil dinucleoside triphosphates, such as Up3U 19a and the more potent analogue MRS2957 19b, have been used as moderately selective P2Y6R agonists.23 P2Y6R agonists such as MRS2957 both promote insulin release and prevent TNF-induced apoptosis in pancreatic islets cells in culture, which might prove useful in the treatment of diabetes.62

The P2Y6R-preferred conformation of the ribose ring is the opposite twist from that preferred by the P2Y1R. Initially, the locked South (S)-conformation was predicted to be favored by Monte Carlo computer simulation of docking of various nucleotide conformations to the P2Y6R, and this prediction was later confirmed by chemical synthesis and pharmacological comparison with UDP.40 In fact, the methanocarba-UDP isomer that maintains a South (S) conformation 25 is roughly twice as potent as UDP, and the corresponding (N)-methanocarba analogue of UDP (not shown) is inactive.

Few antagonists of the P2Y6R have been reported. MRS 2578 49 is a non-competitive P2Y6R antagonist that is predicted to react irreversibly with the receptor because of the essential two isothiocyanate groups.52 However, it has disadvantages as a pharmacological probe, such as limited aqueous stability and low solubility.

P2Y11R

ATPγS 7 is among the most potent P2Y11R agonists, but selective nucleotide activators of this receptor have not been reported. However, a derivative of suramin, NF546 43, was found to activate the P2Y11R selectively.53 Curiously, other suramin derivatives such as NF 157 42, antagonize the P2Y11R, but not in a fully selective fashion. The suramin antagonist derivative NF340 44 appears to be selective for the P2Y11R.

Some potent adenine nucleotide antagonists of the P2Y12R, e.g. 5′-triphosphates, were found to activate the P2Y11R, and therefore should be used with caution in pharmacological experiments. For example, 2-propylthio-β,γ-dichloromethylene-ATP (AR-C 67085 33b) activates the P2Y11R with an EC50 value of 1.5 μM.

P2Y12R

ADP 1 is the native agonist of the P2Y12R, and 2-MeSADP 3 is more potent at this subtype. 5′-Triphosphates such as AR-C 69931MX 34 (Cangrelor), act as competitive antagonists of the P2Y12R and consequently display potent antithrombotic activity.55 Many novel nucleotide and nonnucleotide P2Y12R antagonists have been explored.56–60 Several thienopyridine derivatives that are widely used antithrombotic agents act as prodrugs of potent and irreversibly binding P2Y12R antagonists, i.e. Clopidgrel 53a and Prasugrel 54a and their active metabolites 53b and 54b, respectively. AZD 6140 37 (Ticagrelor) is a nucleoside derivative that acts as a potent, reversible P2Y12R antagonist and is now in clinical use. PSB-0739 39, is a potent nonnucleotide P2Y12R antagonist derived from Reactive blue 2 38.15

P2Y13R

The native agonist of the P2Y13R is ADP 3, and unlike at P2Y1 and P2Y12Rs, 2-MeSADP 3 is less active. ATP 2 is also much weaker and less efficacious. P2Y13R agonists have been suggested for the treatment of dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis.61 Various pyridoxal phosphates were screened for antagonist potency at the human P2Y13R, and MRS 2211 48 proved to be more potent and selective than the parent antagonists PPADS 46 and iso-PPADS 47.

P2Y14R

UDP-glucose 27 and UDP 13 are native agonists of the P2Y14R, and other UDP-sugars also activate the receptor but at higher concentrations. MRS 2690 28, the 2-thio derivative of UDP-glucose, is a potent and selective agonist at the P2Y14R. UDP-glucose but not MRS2690 can activate the P2Y2R. The most potent agonist of the P2Y14R yet reported, α,β-methylene-2-thio analogue MRS2905 26, and its related analogue α,β-Difluoromethylene-UDP, MRS 2802 25, are highly selective agonists of the P2Y14R in comparison to the P2Y6R. The P2Y14R facilitates release of mediators from mast cells, and thus might be a target for asthma.63 Several classes of P2Y14R antagonists of nanomolar affinity, including PPTN 56, were recently reported.64 PPTN was shown to decrease the release from human LAD2 mast cells that was facilitated by a P2Y14R agonist.69

Conclusion

The development of selective ligands of the two subclasses of P2YRs has progressed in recent years to provide selective agonists and antagonists for many but not all of the subtypes. Ligand design has been aided by insights from structural probing using molecular modelling and mutagenesis. The current molecular modelling is often based on the X-ray structure of the CXCR4 receptor, which is the closest to the P2Y receptors among all the currently crystallized receptors in terms of sequence similarity and key structural features. It is now a challenge to develop novel and selective P2YR ligands for disease treatment (although antagonists of the P2Y12R are already widely used as antithrombotics).

There have been significant recent advances in the structural probing of P2YRs and in the medicinal chemistry of selective ligands and their pharmacology. Potent purine and pyrimidine nucleotide analogues that selectively interact with P2YRs have aided in the characterization of regulation of many physiological and pathophysiological processes. It is apparent that this ubiquitous cell signaling system has implications for understanding and treating many diseases. Thus, this field has provided fertile ground for pharmaceutical development.

Contributor Information

Kenneth A. Jacobson, Email: kennethj@helix.nih.gov, Molecular Recognition Section, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bldg. 8A, Rm. B1A-19, Bethesda, Maryland 20892-0810, USA.

M.P. Suresh Jayasekara, Email: pushpa.mudiyanselage@nih.gov, Molecular Recognition Section, Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bldg. 8A, Rm. 1A-20, Bethesda, Maryland 20892-0810, USA.

Stefano Costanzi, Email: costanzi@american.edu, Department of Chemistry, American University, Washington, DC 20016, USA.

References

- 1.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, Fumagalli M, King BF, Gachet C, Jacobson KA, Weisman GA. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII. Update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: From molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjarnadottir TK, Gloriam DE, Hellstrand SH, Kristiansson H, Fredriksson R, Schiöth HB. Comprehensive repertoire and phylogenetic analysis of the G protein-coupled receptors in human and mouse. Genomics. 2006;88:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costanzi S, Mamedova L, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. Architecture of P2Y nucleotide receptors: Structural comparison based on sequence analysis, mutagenesis, and homology modeling. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5393–5404. doi: 10.1021/jm049914c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qi AD, Kennedy C, Harden TK, Nicholas RA. Differential coupling of the human P2Y11 receptor to phospholipase C and adenylyl cyclase. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:318–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson KA, Boeynaems J-M. P2Y nucleotide receptors: Promise of therapeutic applications. Drug Disc Today. 2010;15:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Springthorpe B, Bailey A, Barton P, Birkinshaw TN, Bonnert RV, Brown RC, Chapman D, Dixon J, Guile SD, Humphries RG, Hunt SF, Ince F, Ingall AH, Kirk IP, Leeson PD, Leff P, Lewis RJ, Martin BP, McGinnity DF, Mortimore MP, Paine SW, Pairaudeau G, Patel A, Rigby AJ, Riley RJ, Teobald BJ, Tomlinson W, Webborn PJ, Willis PA. From ATP to AZD6140: the discovery of an orally active reversible P2Y12 receptor antagonist for the prevention of thrombosis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:6013–6018. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erb L, Garrad R, Wang Y, Quinn T, Turner JT, Weisman GA. Site-directed mutagenesis of P2U purinoceptors. Positively charged amino acids in transmembrane helices 6 and 7 affect agonist potency and specificity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4185–4188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Q, Guo D, Lee BX, Van Rhee AM, Kim YC, Nicholas RA, Schachter J, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. A mutational analysis of residues essential for ligand recognition at the human P2Y1 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:499–507. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.3.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moro S, Guo D, Camaioni E, Boyer JL, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Human P2Y1 receptor: Molecular modeling and site-directed mutagenesis as tools to identify agonist and antagonist recognition sites. J Med Chem. 1998;41:1456–1466. doi: 10.1021/jm970684u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ecke D, Fischer B, Reiser G. Diastereoselectivity of the P2Y11 nucleotide receptor: Mutational analysis. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:1250–1255. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo D, von Kügelgen I, Moro S, Kim YC, Jacobson KA. Evidence for the recognition of non-nucleotide antagonists within the transmembrane domains of the human P2Y1 receptor. Drug Devel Res. 2002;57:173–181. doi: 10.1002/ddr.10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillmann P, Ko GY, Spinrath A, Raulf A, von Kügelgen I, Wolff SC, Nicholas RA, Kostenis E, Höltje HD, Müller CE. Key determinants of nucleotide-activated G protein-coupled P2Y2 receptor function revealed by chemical and pharmacological experiments, mutagenesis and homology modeling. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2762–2775. doi: 10.1021/jm801442p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann C, Moro S, Nicholas RA, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. The role of amino acids in extracellular loops of the human P2Y1 receptor in surface expression and activation processes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14639–14647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann K, Sixel U, Di Pasquale F, von Kügelgen I. Involvement of basic amino acid residues in transmembrane regions 6 and 7 in agonist and antagonist recognition of the human platelet P2Y12-receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann K, Baqi Y, Morena MS, Glänzel M, Müller CE, von Kügelgen I. Interaction of new, very potent non-nucleotide antagonists with Arg256 of the human platelet P2Y12 receptor. J Pharm Exp Therap. 2009;331:648–655. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi AD, Zambon AC, Insel PA, Nicholas RA. An arginine/glutamine difference at the juxtaposition of transmembrane domain 6 and the third extracellular loop contributes to the markedly different nucleotide selectivities of human and canine P2Y11 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:1375–1382. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.6.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zylberg J, Ecke D, Fischer B, Reiser G. Structure and ligand-binding site characteristics of the human P2Y11 nucleotide receptor deduced from computational modelling and mutational analysis. Biochem J. 2007;405:277–286. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao Y, Zhang L, Jin J, Ashby B, Kunapuli SP. Mutational analysis of residues important for ligand interaction with the human P2Y12 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;644:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivanov AA, Ko H, Cosyn L, Maddileti S, Besada P, Fricks I, Costanzi S, Harden TK, Van Calenbergh S, Jacobson KA. Molecular modeling of the human P2Y2 receptor and design of a selective agonist, 2′-amino-2′-deoxy-2-thiouridine 5′-triphosphate. J Med Chem. 2007;50:1166–1176. doi: 10.1021/jm060903o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nandanan E, Jang SY, Moro S, Kim HO, Siddiqui MA, Russ P, Marquez VE, Busson R, Herdewijn P, Harden TK, Boyer JL, Jacobson KA. Synthesis, biological activity, and molecular modeling of ribose-modified deoxyadenosine bisphosphate analogues as P2Y1 receptor ligands. J Med Chem. 2000;43:829–842. doi: 10.1021/jm990249v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Major DT, Nahum V, Wang Y, Reiser G, Fischer B. Molecular recognition in purinergic receptors. 2. Diastereoselectivity of the hP2Y1-receptor. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4405–4416. doi: 10.1021/jm049771u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson KA, Costanzi S, Ivanov AA, Tchilibon S, Besada P, Gao ZG, Maddileti S, Harden TK. Structure activity and molecular modeling analyses of ribose- and base-modified uridine 5′-triphosphate analogues at the human P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:540–549. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Besada P, Shin DH, Costanzi S, Ko H, Mathé C, Gagneron J, Gosselin G, Maddileti S, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Structure-activity relationships of uridine 5′-diphosphate analogues at the human P2Y6 receptor. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5532–5543. doi: 10.1021/jm060485n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maruoka H, Jayasekara MP, Barrett MO, Franklin DA, de Castro S, Kim N, Costanzi S, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Pyrimidine nucleotides with 4-alkyloxyimino and terminal tetraphosphate d-ester modifications as selective agonists of the P2Y4 receptor. J Med Chem. 2011;54:4018–4033. doi: 10.1021/jm101591j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yelovitch S, Barr HM, Camden J, Weisman GA, Shai E, Varon D, Fischer B. Identification of a Promising Drug Candidate for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Based on a P2Y1 Receptor Agonist. J Med Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1021/jm 3006355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunschweiger A, Müller CE. P2 receptors activated by uracil nucleotides--an update. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:289–312. doi: 10.2174/092986706775476052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfefferkorn JA, Choi C, Winters T, Kennedy R, Chi L, Perrin LA, Ping YW, McClanahan T, Schroeder R, Leininger MT, Geyer A, Schefzick S, Atherton J. P2Y1 receptor antagonists as novel antithrombotic agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3338–3343. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eliahu S, Barr HM, Camden J, Weisman GA, Fischer B. A novel insulin secretagogue based on a dinucleoside polyphosphate scaffold. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2472–2481. doi: 10.1021/jm901621h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Tayeb A, Qi A, Müller CE. Synthesis and structure activity relationships of uracil nucleotide derivatives and analogs as agonists at human P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7076–7087. doi: 10.1021/jm060848j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Tayeb A, Qi A, Nicholas RA, Müller CE. Structural modifications of UMP, UDP, and UTP leading to subtype-selective agonists for P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6 receptors. 2011;54:2878–2890. doi: 10.1021/jm1016297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Rhee AM, Fischer B, van Galen PJ, Jacobson KA. Modelling the P2Y purinoceptor using rhodopsin as template. Drug Design Discov. 1995;13:133–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moro S, Jacobson KA. Molecular modeling as a tool to investigate molecular recognition in P2Y receptors. Curr Pharmaceut Design. 2002;8:99–110. doi: 10.2174/1381612023392892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Major DT, Fischer B. Molecular recognition in purinergic receptors. 1. A comprehensive computational study of the hP2Y1-receptor. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4391–4404. doi: 10.1021/jm049772m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deflorian F, Jacobson KA. Comparison of three GPCR structural templates for modeling of the P2Y12 nucleotide receptor. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2011;25:329–338. doi: 10.1007/s10822-011-9423-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivanov AA, Costanzi S, Jacobson KA. Defining the nucleotide binding sites of P2Y receptors using rhodopsin-based homology modeling. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2006;20:417–426. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. In: Conn PM, Sealfon SC, editors. Methods in Neurosciences. Vol. 25. Academic Press; USA: 1995. pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, Le Trong I, Teller DC, Okada T, Stenkamp RE, Yamamoto M, Miyano M. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cherezov V, Rosenbaum D, Hanson M, Rasmussen S, Thian F, Kobilka T, Choi H, Kuhn P, Weis W, Kobilka B, Stevens R. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human 2 adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu B, Chien EYT, Mol CD, Fenalti G, Liu W, Katritch V, Abagyan R, Brooun A, Wells P, Bi FC, Hamel DJ, Kuhn P, Handel TM, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science. 2010;330:1066–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1194396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costanzi S, Joshi BV, Maddileti S, Mamedova L, Gonzalez-Moa MJ, Marquez VE, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Human P2Y6 receptor: Molecular modeling leads to the rational design of a novel agonist based on a unique conformational preference. J Med Chem. 2005;48:8108–8111. doi: 10.1021/jm050911p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baqi Y, Weyler S, Iqbal J, Zimmermann H, Müller CE. Structure-activity relationships of anthraquinone derivatives derived from bromaminic acid as inhibitors of ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (E-NTPDases) Purinergic Signalling. 2009;5:91–106. doi: 10.1007/s11302-008-9103-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hechler B, Gachet C. P2 receptors and platelet function. Purinergic Signal. 2011;4:293–303. doi: 10.1007/s11302-011-9247-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chhatriwala M, Ravi RG, Patel RI, Boyer JL, Jacobson KA, Harden TK. Induction of novel agonist selectivity for the ADP-activated P2Y1 receptor versus the ADP-activated P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors by conformational constraint of an ADP analogue. J Pharm Exp Therap. 2004;311:1038–1043. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyer JL, Romero-Avila T, Schachter JB, Harden TK. Identification of competitive antagonists of the P2Y1 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:1323–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cattaneo M, Lecchi A, Joshi BV, Ohno M, Besada P, Tchilibon S, Lombardi R, Bischofberger N, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Antiaggregatory activity in human platelets of potent antagonists of the P2Y1 receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1995–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaver SR, Rideout JL, Pendergast W, Douglass JG, Brown EG, Boyer JL, Patel RI, Redick CC, Jones AC, Picher M, Yerxa BR. Structure-activity relationships of dinucleotides: Potent and selective agonists of P2Y receptors. Purinergic Signalling. 2005;1:183–191. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-0648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yerxa BR, Sabater JR, Davis CW, Stutts MJ, Lang-Furr M, Picher M, Jones AC, Cowlen M, Dougherty R, Boyer J, Abraham WM, Boucher RC. Pharmacology of INS37217 [P(1)-(uridine 5′)-P(4)-(2′-deoxycytidine 5′)tetraphosphate, tetrasodium salt], a next-generation P2Y2 receptor agonist for the treatment of cystic fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:871–880. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maruoka H, Barrett MO, Ko H, Tosh DK, Melman A, Burianek LE, Balasubramanian R, Berk B, Costanzi S, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Pyrimidine ribonucleotides with enhanced selectivity as P2Y6 receptor agonists: Novel 4-alkyloxyimino, (S)-methanocarba, and 5′-triphosphate γ-ester modifications. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4488–4501. doi: 10.1021/jm100287t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Poecke S, Barrett MO, Kumar TS, Sinnaeve D, Martins JC, Jacobson KA, Harden TK, Van Calenbergh S. Synthesis and P2Y2 receptor agonist activity of nucleotide 5′-phosphonate analogues. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:2304–2315. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weyler S, Baqi Y, Hillmann P, Kaulich M, Hunder AM, Müller IA, Müller CE. Combinatorial synthesis of anilinoanthraquinone derivatives and evaluation as non-nucleotidederived P2Y2 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harden TK, Sesma JI, Fricks IP, Lazarowski ER. Signaling and pharmacological properties of the P2Y14 receptor. Acta Physiol. 2010;199:149–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Kügelgen I, Harden TK. Molecular pharmacology, physiology, and structure of the P2Y receptors. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:373–415. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meis S, Hamacher A, Hongwiset D, Marzian C, Wiese M, Eckstein N, Royer HD, Communi D, Boeynaems JM, Hausmann R, Schmalzing G, Kassack MU. NF546 [4,4′-(carbonylbis(imino-3,1-phenylene-carbonylimino-3,1-(4-methyl-phenylene)-carbonylimino))-bis(1,3-xylene-alpha,alpha’-diphosphonic acid) tetrasodium salt] is a non-nucleotide P2Y11 agonist and stimulates release of interleukin-8 from human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Pharm Exp Therap. 2010;332:238–247. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.157750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ginsburg-Shmuel T, Haas M, Schumann M, Reiser G, Kalid O, Stern N, Fischer B. 5-OMe-UDP is a potent and selective P2Y6-receptor agonist. J Med Chem. 2010;53:1673–1685. doi: 10.1021/jm901450d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ingall AH, Dixon J, Bailey A, Coombs ME, Cox D, McInally IJ, Hunt SF, Kindon ND, Teobald BJ, Willis PA, Humphries RG, Leff P, Clegg JA, Smith JA, Tomlinson W. Antagonists of the platelet P2T receptor: A novel approach to antithrombotic therapy. J Med Chem. 1999;42:213–220. doi: 10.1021/jm981072s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Tayeb A, Griessmeier KJ, Müller CE. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of [3H]PSB-0413, a selective antagonist radioligand for platelet P2Y12 receptors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:5450–5452. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.08.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang H, Liu J, Zhang L, Kong L, Yao H, Sun H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of ticagrelor derivatives as novel antiplatelet agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:3598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson FL, Boyer JL, Leese PT, Crean C, Krishnamoorthy R, Durham T, Fox AW, Kellerman DJ. Rapid and reversible modulation of platelet function in man by a novel P2Y12 ADP-receptor antagonist, INS50589. Platelets. 2007;18:346–56. doi: 10.1080/09537100701268741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baqi Y, Atzler K, Köse M, Glänzel M, Müller CE. High-affinity, non-nucleotide-derived competitive antagonists of platelet P2Y12 receptors. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3784–3793. doi: 10.1021/jm9003297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parlow JJ, Burney MW, Case BL, Girard TJ, Hall KA, Harris PK, Hiebsch RR, Huff RM, Lachance RM, Mischke DA, Rapp SR, Woerndle RS, Ennis MD. Piperazinyl Glutamate Pyridines as Potent Orally Bioavailable P2Y12 Antagonists for Inhibition of Platelet Aggregation. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2010–2037. doi: 10.1021/jm901518t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fabre AC, Malaval C, Ben Addi A, Verdier C, Pons V, Serhan N, Lichtenstein L, Combes G, Huby T, Briand F, et al. P2Y13 Receptor is Critical for Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Hepatology. 2010;52:1477–1483. doi: 10.1002/hep.23897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balasubramanian R, Ruiz de Azua I, Wess J, Jacobson KA. Activation of distinct P2Y receptor subtypes stimulates insulin secretion and cytoprotection in MIN6 mouse pancreatic β cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao ZG, Ding Y, Jacobson KA. UDP-glucose acting at P2Y14 receptors is a mediator of mast cell degranulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gauthier JY, Belley M, Deschênes D, Fournier JF, Gagné S, Gareau Y, et al. The identification of 4,7-disubstituted naphthoic acid derivatives as UDP-competitive antagonists of P2Y14. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2836–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herpin TF, Morton G, Rehfuss RP, Lawrence RM, Poss MA, Roberge JY, Gungor T. Aminobenzazoles as P2Y1 receptors inhibitors. WO2005070920. August. 2005;4:2005. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morales-Ramos AI, Mecom JS, Kiesow TJ, Graybill TL, Brown GD, Aiyar NV, Davenport EA, Kallal LA, Knapp-Reed BA, Li P, Londregan AT, Morrow DM, Senadhi S, Thalji RK, Zhao S, Burns-Kurtis CL, Marino JP., Jr Tetrahydro-4-quinolinamines identified as novel P2Y1 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:6222–6226. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thalji RK, Aiyar NV, Davenport EA, Erhardt JA, Kallal LA, Morrow DM, Senadhi S, Burns-Kurtis CL, Marino JP., Jr Benzofuran-substituted urea derivatives as novel P2Y1 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:4104–4107. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Costanzi S, Kumar TS, Balasubramanian R, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Virtual screening leads to the discovery of novel non-nucleotide P2Y1 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.06.044. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao ZG, Wei Q, Jayasekara MPS, Jacobson KA. The role of P2Y14 and other P2Y receptors in degranulation of human LAD2 mast cells. Purinergic Signalling. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9325-4. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ginsburg-Shmuel T, Haas M, Grbic D, Arguin G, Nadel Y, Gendron FP, Reiser G, Fischer B. UDP made a highly promising stable, potent, and selective P2Y6-receptor agonist upon introduction of a boranophosphate moiety. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.07.042. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]