Abstract

The steady-state {1H}-15N NOE experiment is used in most common NMR analyses of backbone dynamics to accurately ascertain the effects of the fast dynamic modes. We demonstrate here that, in its most common implementation, this experiment generates an incorrect steady state in the presence of CSA/dipole cross-correlated relaxation leading to large errors in the characterization of these high-frequency modes. This affects both the quantitative and qualitative interpretation of 15N backbone relaxation in dynamic terms. We demonstrate further that minor changes in the experimental implementation effectively remove these errors and allow a more accurate interpretation of protein backbone dynamics.

Dynamics are essential for protein function. Fast motions that are important for protein interactions1 can also be linked to slower motions involved in enzyme catalysis.2 The measurement of backbone 15N relaxation rates in NMR has become a routine procedure3,4 to characterize fast local motions.5,6 These measurements can be complemented by other relaxation data to obtain a more refined view of backbone dynamics.7 Usually, the 15N relaxation rates employed to characterize fast protein dynamics are the longitudinal relaxation rate R1, the transverse relaxation rate R2 and the dipolar cross-relaxation rate between the 15N and 1H nuclei.8 The last of these rates is essential for the accurate estimation of the spectral density function at high frequency5,9 and crucial for the identification of fast backbone motions.10,11 This rate is derived from what is commonly called the ‘NOE experiment’ where the ratio between the steady-state longitudinal 15N polarization under 1H irradiation or at equilibrium without any perturbation, is measured.8,12 The saturation of 1H’s is more difficult to achieve than previously assumed, and cross-correlated relaxation13 affects the steady-state 15N polarization during 1H irradiation. We quantify these errors for the 1H irradiation scheme12 commonly used in the ‘NOE experiment’ and show that they can be suppressed in a straightforward manner, leading to more accurate measurements of spectra density at high frequency.

Several schemes have been proposed for 1H irradiation in steady-state NOE experiments. Although composite pulse decoupling15 can be used, the most common procedure applies a series of pulses and delays.12,14 Pulses with a variety of flip angles have been advocated,14 and schemes with 120° pulses are the most popular, based on empirical observations.16 Surprisingly, theoretical and experimental studies of irradiation schemes are sparse.14,17 We have recently shown that the symmetry of the saturation scheme is important.11 Here, we reexamine the accuracy of the experiment as a function of the 1H saturation scheme utilizing the Homogeneous Liouville Equation formalism. 17,18

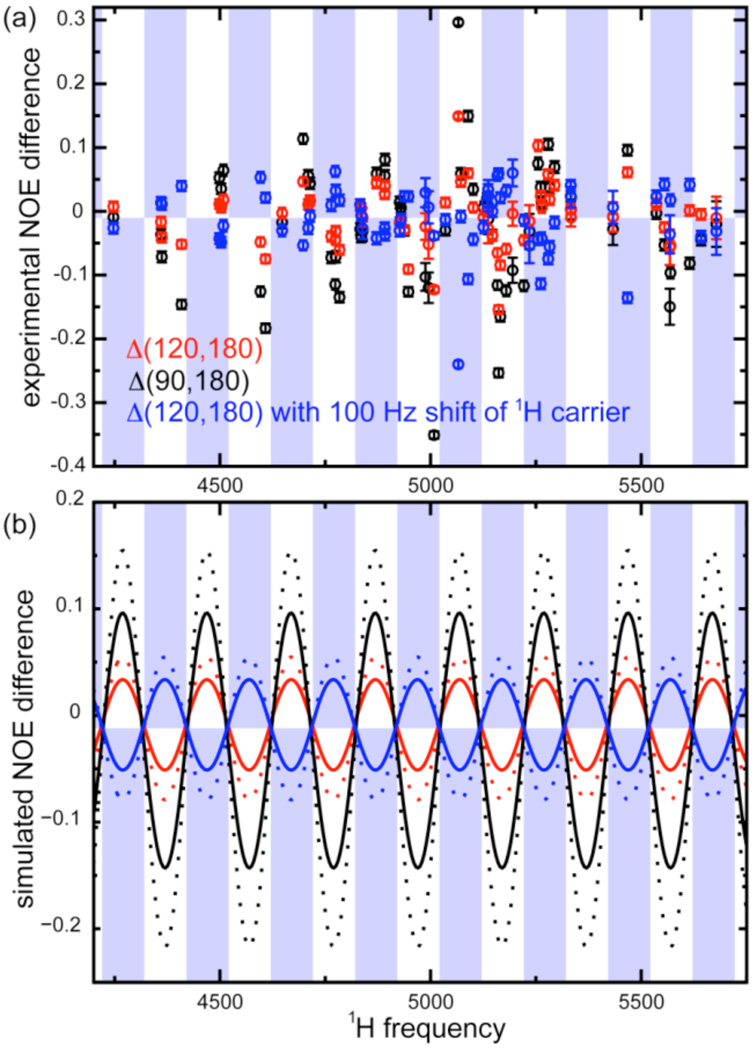

All experiments were performed on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance spectrometer equipped with a room-temperature probe, using a sample of perdeuterated and 15N-labelled human ubiquitin (0.5 mM, in 50 mM ammonium acetate, 300 mM NaCl, pH 4.8). We measured 15N{1H} Overhauser effects using a symmetric proton irradiation scheme composed of repeated elements [delay τ/2 – β pulse – delay τ/2]n. Experiments were performed with flip angles β = 90°, 120° and 180°. In Figure 1a, we show differences, Δ(β1,β2), in the NOE ratio (of intensities with and without 1H irradiation) obtained with different flip angles β. Deviations are significant with β = 120° and maximal for β = 90°. As highlighted by color in Figure 1a (e.g. blue points appear on a blue background), the deviations are a periodic function of the 1H carrier frequency, with a period of 200 Hz, which corresponds to the inverse of the interval between two pulses τ. A 100 Hz shift of the 1H carrier leads to an inversion of all deviations, i.e., to a phase shift π of the periodic function. This observation is rationalized by numerical simulations (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Experimentally observed deviations of the NOE ratio, Δ(β,180) for rigid NH pairs measured with β = 120° (o); β = 90° (o); and β = 120° (o) with the 1H carrier frequency shifted by 100 Hz from 2820 to 2720 Hz. The blue boxes illustrate the periodic oscillation with a 200 Hz period. (b) Numerical calculations of the deviations of the NOE ratio for a rigid NH pair (solid lines) and a more mobile NH pair (dotted lines), taking CSA/DD cross-correlation into account, color coded as in (a). The delay τ = 5 ms in the experiments with β ≠ 180° and τ = 50 ms for β = 180°. See Supporting Information (SI) for details about the pulse sequence and numerical calculations.

Figure 1b shows that the calculated steady state 15N polarization depends on the 1H carrier frequency, with a period equal to the inverse of the interpulse delay: 1/(τ) = 200 Hz for τ = 5 ms. The oscillations can only be reproduced when the cross-correlation of the 15N chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) and the 15N1H dipolar coupling is included in simulations.

The oscillations seen in Figure 1 stem from a superposition of two separate effects. The dominant one is largest when the evolution under the offset from the 1H carrier and the heteronuclear scalar coupling leads to the conversion Hy → 2HyNz during the interpulse delay τ. If β = 90°, the sequence β – τ – β leads to the conversion Hz → −2HzNz. Subsequent cross-correlated cross-relaxation between 2HzNz and Nz, results in an effective cross-relaxation pathway between the longitudinal polarization operators Hz and Nz, that perturbs the steady state. The second effect is most observable when the dominant effect vanishes, i.e. when the delay τ is a multiple of 1/|1JNH|. The average component Hzav vanishes if the 1H polarization precesses an integer number of full rotations during the delay τ, i.e. at the DANTE condition.19 Otherwise, the polarization Hz is not effectively saturated (Hzav ≠ 0) so that the 15N polarization does not evolve towards the desired steady state.

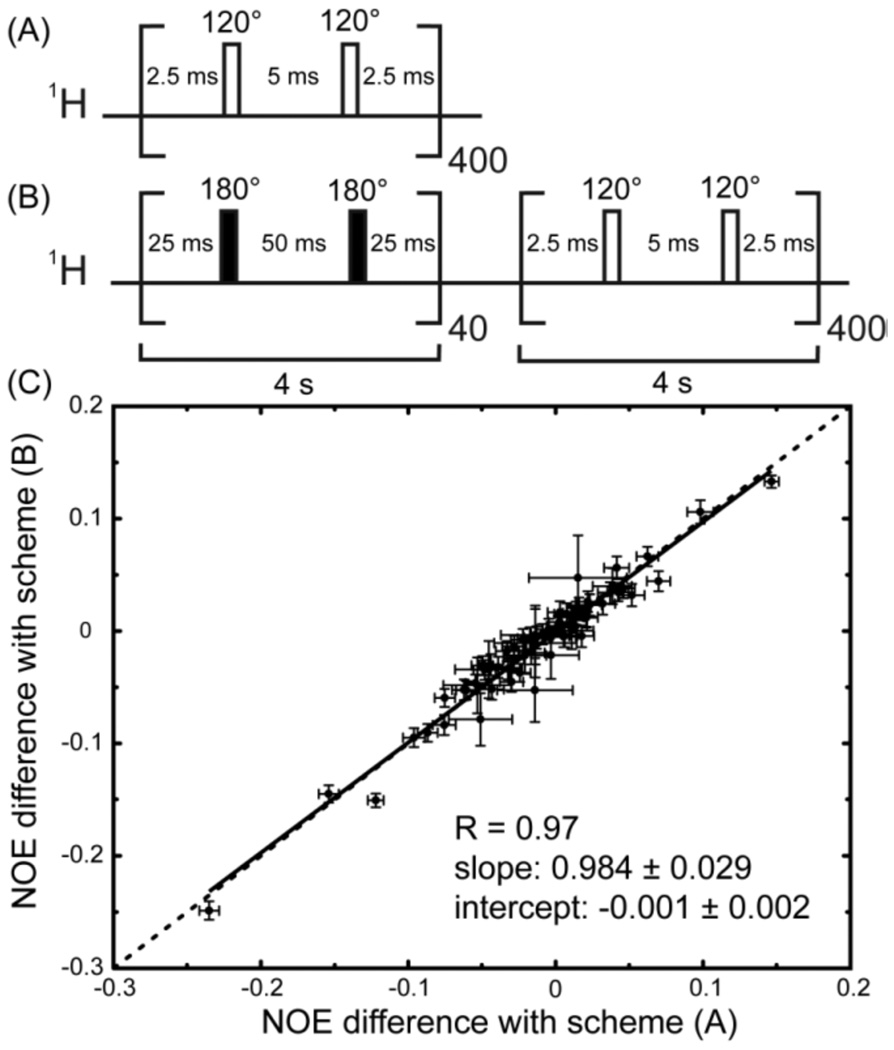

To illustrate the validity of this analysis, consider the experiment described in Figure 2, a “spin-temperature jump”, demonstrating that a scheme like (A) creates a steady state different from the steady state obtained with 180° pulses. Intuitively, one might suppose that proton irradiation with any scheme would lead to proper saturation if applied long enough with sufficient power, so that both irradiation schemes would lead to the same steady state. However, as shown in Figure 2, under a sequence of 120° pulses, the polarization Nz evolves from the ‘ideal’ 15N steady state (achieved after a 4s irradiation with 180° pulses) towards the same state as the one obtained with scheme A. Deviations measured under scheme A correspond to a different steady state and not to a transient effect.

Figure 2.

Spin-temperature jump experiment using a 1H irradiation scheme with β = 120° pulses. (A) starting right after the FID, and (B) starting from a steady state obtained with β = 180° pulses. (C) Correlations of deviations in the NOE ratios obtained using schemes (A) and (B) with those using β = 180° pulses for 4 s.

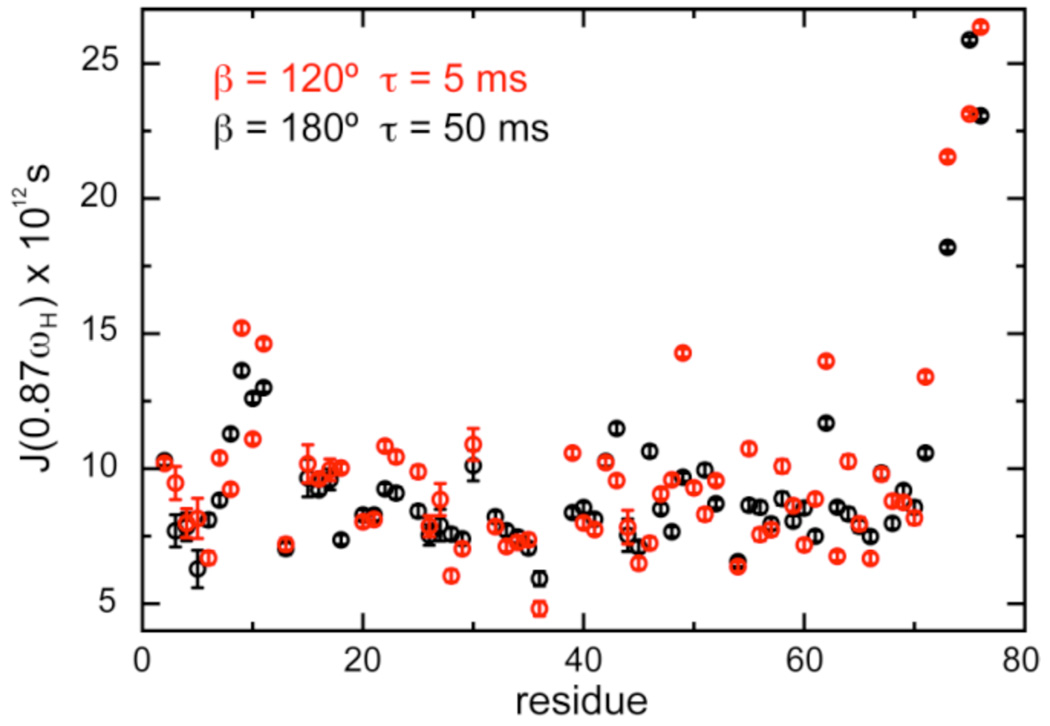

Figure 3 shows how systematic errors due to imperfect saturation propagate to the derived spectral density function at high frequency.12 This value is essential to the quantitative analysis of relaxation data.3,20 Deviations in the NOE ratios are amplified, so that large deviations are observed (with a maximum of 47% for Gln49, see SI). When an improper irradiation scheme is used, qualitative interpretations may be biased; for example, high-frequency motions seem to vary significantly in the β-hairpin comprising residues 9–11, while they appear to be uniform with the correct saturation scheme.

Figure 3.

Apparent spectral density function J(0.87ωH), ωH being the 1H Larmor frequency, for backbone NH groups in human ubiquitin derived from longitudinal relaxation rates and different sets of NOE’s.

In conclusion, we have shown that the steady state 15N polarization in NOE experiments depends on the flip angle β employed in the saturation sequence. Widely used trains of 120° pulses do not lead to the ideal steady state because of CSA/DD cross-correlated relaxation. Flip angles β should be set to 180° and delays τ to integer multiples of the inverse of the scalar coupling 1JNH. Improper irradiation leads to significant errors in the estimate of the spectral density functions at high frequency. This effect may be comparable to experimental errors in many studies with low-precision NOE ratios and it occurs whether a protein is deuterated or not (SI).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Geoffrey Bodenhausen and Philippe Pelupessy for their careful reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge support from grants NSF MCB-0347100 (R. G.), NIH GM 47021(DC) and NIH, 5G12 RR06030 (CCNY).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Pulse sequence; NOE ratios; relative errors in J(0.87ωH); NOE deviations (i) with various delays τ and (ii) in protonated ubiquitin; simulations of the effect of the size of the protein; propagation of errors to microdynamic parameters; details of numerical calculations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frederick KK, Marlow MS, Valentine KG, Wand AJ. Nature. 2007;448 doi: 10.1038/nature05959. 325-U3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Showalter SA, Bruschweiler-Li L, Johnson E, Zhang F, Bruschweiler R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6472–6478. doi: 10.1021/ja800201j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dhulesia A, Gsponer J, Vendruscolo M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8931–8939. doi: 10.1021/ja0752080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henzler-Wildman KA, Lei M, Thai V, Kerns SJ, Karplus M, Kern D. Nature. 2007;450 doi: 10.1038/nature06407. 913-U27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kay LE, Torchia DA, Bax A. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8972–8979. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer AG. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3623–3640. doi: 10.1021/cr030413t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrow NA, Zhang OW, Szabo A, Torchia DA, Kay LE. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:153–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00211779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butterwick JA, Loria JP, Astrof NS, Kroenke CD, Cole R, Rance M, Palmer AG. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;339:855–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lienin SF, Bremi L, Brutscher B, Bruschweiler R, Ernst RR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9870–9879. [Google Scholar]; Wang TZ, Cai S, Zuiderweg ERP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8639–8643. doi: 10.1021/ja034077+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ferrage F, Pelupessy P, Cowburn D, Bodenhausen G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11072–11078. doi: 10.1021/ja0600577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, III, Rance M, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and practice. San Diego: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng JW, Wagner G. J. Magn. Reson. 1992;98:308–332. [Google Scholar]; Hansen DF, Yang DW, Feng HQ, Zhou Z, Wiesner S, Bai YW, Kay LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11468–11479. doi: 10.1021/ja072717t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang SL, Hinck AP, Ishima R. J. Biomol. NMR. 2007;38:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrage F, Piserchio A, Cowburn D, Ghose R. J. Magn. Reson. 2008;792:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrow NA, Muhandiram R, Singer AU, Pascal SM, Kay CM, Gish G, Shoelson SE, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman M. J. Magn. Reson. 1984;60:437–499. [Google Scholar]; Kumar A, Grace RCR, Madhu PK. Prog. NMR Spectrosc. 2000;37:191–319. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renner C, Schleicher M, Moroder L, Holak TA. J. Biomol. NMR. 2002;23:23–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1015385910220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levitt MH, Freeman R, Frenkiel T. J. Magn. Reson. 1982;47:328–330. [Google Scholar]; Skelton NJ, Palmer AG, Akke M, Kordel J, Rance M, Chazin WJ. J. Magn. Reson. Ser. B. 1993;102:253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markley JL, Horsley WJ, Klein MP. J. Chem. Phys. 1971;55:3604. &. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levitt MH, Di Bari L. Bull. Magn. Reson. 1993;16:94–114. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levitt MH, Di Bari L. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992;69:3124–3127. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ghose R. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2000;12:152–172. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris GA, Freeman R. J. Magn. Reson. 1978;29:433–462. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akke M, Brüschweiler R, Palmer AG., III J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:9832–9833. [Google Scholar]; Tugarinov V, Liang ZC, Shapiro YE, Freed JH, Meirovitch E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3055–3063. doi: 10.1021/ja003803v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Massi F, Palmer AG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11158–11159. doi: 10.1021/ja035605k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.