Abstract

Fluid and macromolecule secretion by submucosal glands in mammalian airways is believed to be important in normal airway physiology and in the pathophysiology of cystic fibrosis (CF). An in situ fluorescence method was applied to measure the ionic composition and viscosity of freshly secreted fluid from airway glands. Fragments of human large airways obtained at the time of lung transplantation were mounted in a humidified perfusion chamber and the mucosal surface was covered by a thin layer of oil. Individual droplets of secreted fluid were microinjected with fluorescent indicators for measurement of [Na+], [Cl−], and pH by ratio imaging fluorescence microscopy and viscosity by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. After carbachol stimulation, 0.1–0.5 μl of fluid accumulated in spherical droplets at gland orifices in ≈3–5 min. In gland fluid from normal human airways, [Na+] was 94 ± 8 mM, [Cl−] was 92 ± 12 mM, and pH was 6.97 ± 0.06 (SE, n = 7 humans, more than five glands studied per sample). Apparent fluid viscosity was 2.7 ± 0.3-fold greater than that of saline. Neither [Na+] nor pH differed in gland fluid from CF airways, but viscosity was significantly elevated by ≈2-fold compared to normal airways. These results represent the first direct measurements of ionic composition and viscosity in uncontaminated human gland secretions and indicate similar [Na+], [Cl−], and pH to that in the airway surface liquid. The elevated gland fluid viscosity in CF may be an important factor promoting bacterial colonization and airway disease.

Keywords: ASL, chloride, trachea, ratio imaging

The air-facing surface of respiratory airways is lined by a layer of surface epithelial cells whose mucosa is bathed by a thin film of fluid called the airway surface liquid (ASL) (1–5). The airways also contain submucosal glands that secrete fluid and macromolecules onto the ASL (6–9). The submucosal glands contain serous tubules and acini that secrete salt, water, and various antimicrobial proteins. The serous secretions pass through mucous tubules, where viscous glycoproteins are added, and then into a collecting duct and onto the airway surface. Active salt and water secretion by serous epithelial cells is believed to involve Cl− transport by the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein (10–12) driving water transport through AQP4 and AQP5 water channels (13–15). Submucosal gland secretions are proposed to be important for generation of ASL fluid and for creation of an environment that inhibits bacterial colonization.

Abnormalities in submucosal gland secretions have been proposed to contribute to the airway pathophysiology in cystic fibrosis (CF). CFTR is expressed in serous epithelial cells of submucosal glands more strongly than in other tissues of the airways and lung (16, 17). Autopsy specimens from neonates with CF but who have not yet developed lung disease show distended lumens in submucosal glands, which were interpreted to indicate mucus accumulation (18), but others report normal CF gland morphology (19). Cell culture measurements have indicated abnormal Cl− and fluid transport in gland epithelial cells from CF patients (12, 20, 21). It was thus postulated that the salt content and viscosity of submucosal glandular secretions in CF are abnormal (22). In addition, based on reported functional interactions between CFTR and a Cl−/HCO exchanger (23) and transport of HCO

exchanger (23) and transport of HCO by CFTR (24), it has been postulated that the pH of glandular secretions in CF individuals is abnormal.

by CFTR (24), it has been postulated that the pH of glandular secretions in CF individuals is abnormal.

The purpose of this study was to measure [Na+], [Cl−], pH and viscosity of freshly secreted fluid from human submucosal airway glands to determine: (i) whether the composition of fluid secreted from glands is similar to that of the ASL, and (ii) whether gland fluid composition differs in normal vs. CF human airways. We recently developed fluorescent probes and ratio imaging microscopy methods to measure [Na+], [Cl−], and pH in the ASL in airway cell culture models and in intact trachea (25). Similar fluorescence methods are applied here in which fresh gland secretions in bronchi are visualized and labeled with fluorescent indicators by direct microinjection of fluorescent dyes. Ratio imaging analysis permitted accurate determination of [Na+], [Cl−], and pH in gland fluid, and a fluorescence photobleaching approach was developed for quantitative measurement of gland fluid viscosity.

Methods

Airway Preparations.

Fragments of normal and CF human airways were obtained after lung transplantation and consisted of scrap airway trimmings from normal donor lungs and larger tissue fragments from discarded CF lungs. Tissues were placed in cold Physiosol (Abbott) within 30 min after removal for transport to the laboratory and initial dissection. Tissues were then transferred to ice-cold HCO -buffered Krebs solution (see below) and continuously gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Tissues were cut into rectangles of ≈2 cm2, and a 1.5- to 2-mm thick layer containing the mucosa and submucosa was dissected away from the underlying cartilage. Two different procedures were used to mount the tissues. In the first procedure, tissues were placed over a wire mesh in a tissue culture well with HCO

-buffered Krebs solution (see below) and continuously gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Tissues were cut into rectangles of ≈2 cm2, and a 1.5- to 2-mm thick layer containing the mucosa and submucosa was dissected away from the underlying cartilage. Two different procedures were used to mount the tissues. In the first procedure, tissues were placed over a wire mesh in a tissue culture well with HCO -containing media bathing the serosa and left in a cell culture incubator for 30 min. The airway fragment was then mounted by using pins on a sponge soaked in HCO

-containing media bathing the serosa and left in a cell culture incubator for 30 min. The airway fragment was then mounted by using pins on a sponge soaked in HCO -containing Kreb's buffer (120 mM NaCl/25 mM NaHCO3/3.3 mM KH2PO4/0.8 mM K2HPO4/1.2 mM MgCl2/1.2 mM CaCl2/10 mM glucose, pH 7.4) (on the serosal side) and held in a perfusion chamber with the mucosal side up in a humidified 5% CO2/air atmosphere at 37°C (see Fig. 1A). In the second procedure, the tissues were mounted on a Sylgard-lined Petri dish by using pins with the mucosal side facing up and with the serosal side bathed in Kreb's buffer. In both procedures, the mucosa was then washed with saline, dried by using a cotton swab and nitrogen stream, and covered with oil (5–10 μl/cm2 tissue). At 3–5 min after addition of carbachol (10 μM) to the serosal bathing solution to stimulate gland secretion, individual droplets of freshly secreted gland fluid were microinjected with 2.3 or 4.6 nl of Kreb's buffer containing the fluorescent indicators by using a Nanoject–II microinjector (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA). At the time of measurement, the droplet volumes were 0.1–0.5 μl, so that the contribution of injected Krebs buffer to the gland fluid was <5%.

-containing Kreb's buffer (120 mM NaCl/25 mM NaHCO3/3.3 mM KH2PO4/0.8 mM K2HPO4/1.2 mM MgCl2/1.2 mM CaCl2/10 mM glucose, pH 7.4) (on the serosal side) and held in a perfusion chamber with the mucosal side up in a humidified 5% CO2/air atmosphere at 37°C (see Fig. 1A). In the second procedure, the tissues were mounted on a Sylgard-lined Petri dish by using pins with the mucosal side facing up and with the serosal side bathed in Kreb's buffer. In both procedures, the mucosa was then washed with saline, dried by using a cotton swab and nitrogen stream, and covered with oil (5–10 μl/cm2 tissue). At 3–5 min after addition of carbachol (10 μM) to the serosal bathing solution to stimulate gland secretion, individual droplets of freshly secreted gland fluid were microinjected with 2.3 or 4.6 nl of Kreb's buffer containing the fluorescent indicators by using a Nanoject–II microinjector (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA). At the time of measurement, the droplet volumes were 0.1–0.5 μl, so that the contribution of injected Krebs buffer to the gland fluid was <5%.

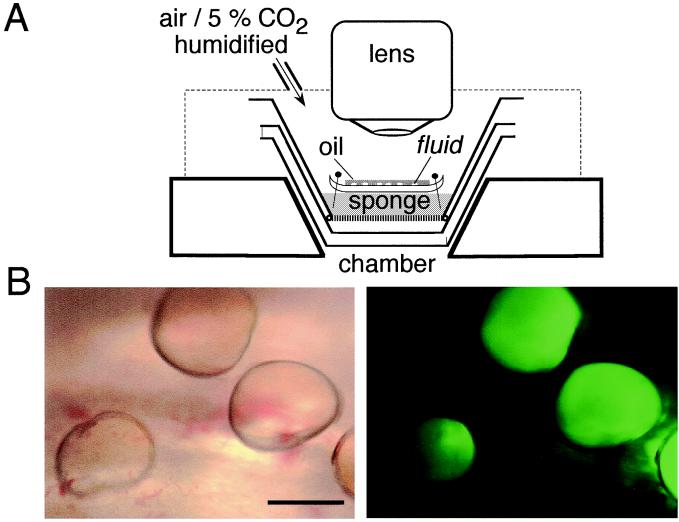

Figure 1.

Microscopy of fluid secretions from freshly excised human bronchi. (A) Schematic of perfusion chamber and microscope. Tissues were fixed with pins on a sponge soaked with HCO -containing physiological buffers. Temperature was maintained at 37°C, and the chamber was surrounded by a moist 5% CO2 atmosphere. (B) Micrographs of fluorescently stained fluid droplets secreted from submucosal glands. Low magnification view of mucosa containing several fluid droplets under brightfield illumination (Left) and fluorescence (Right). (Scale bar, 2 mm.)

-containing physiological buffers. Temperature was maintained at 37°C, and the chamber was surrounded by a moist 5% CO2 atmosphere. (B) Micrographs of fluorescently stained fluid droplets secreted from submucosal glands. Low magnification view of mucosa containing several fluid droplets under brightfield illumination (Left) and fluorescence (Right). (Scale bar, 2 mm.)

Fluorescent Indicators.

[Na+] was measured with 200-nm diameter carboxyl latex beads (Polymer Instruments, Amherst, MA) containing the fluorophores Sodium Red (provided by Molecular Probes, MPR no. 71351) and BODIPY-fl (Molecular Probes). Beads were prepared as described (25). [Cl−] was measured by using a 40-kDa dextran conjugated with the chromophores 6-phenyl-N-(6-carboxyhexyl) quinolinium and 6carboxytetramethylrhodamine as described (25). Quinolinium:tetramethylrhodamine:dextran molar labeling ratio was 4.5:0.5:1. pH was measured by using the dual-excitation wavelength pH indicator BCECF [2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxy fluorescein] conjugated to dextran (Molecular Probes).

Fluorescence Microscopy.

The chamber containing mounted bronchial tissue was positioned on the stage of a Leitz upright fluorescence microscope with a Technical Instruments coaxial-confocal attachment. Fluorescence was measured by using a photomultiplier detector and custom filter sets for quinolinium, tetramethylrhodamine, BCECF, Sodium Red, and BODIPY-fl chromophores. Fluorescence was detected by using a Nikon 50X extra-long working distance air objective (numerical aperture 0.55, working distance 8 mm) for ratiometric determination of [Na+], [Cl−], and pH. Background fluorescence was <1% of total fluorescence for [Na+] and pH measurements, and for tetramethylrhodamine fluorescence in [Cl−] measurements. Background fluorescence (measured in noninjected fluid droplets) was generally ≈40% of total fluorescence for measurement of quinolinium fluorescence in [Cl−] measurements and subtracted.

Photobleaching Measurements.

Photobleaching measurements were done by using an apparatus described previously (26, 27). Bronchial tissues were mounted as described above on the stage of a Nikon upright fluorescence microscope, and gland fluid droplets were microinjected with size-fractionated FITC-dextran (10 kDa). The output of an argon ion laser (488 nm, Innova 70–4; Coherent, Palo Alto, CA) was modulated by an acousto-optic modulator and directed onto the fluorescent droplet by using a Nikon extra-long working distance objective lens (×20, numerical aperture 0.35, working distance 20.5 mm). Illumination intensity was ≈0.2 mW at the sample before the bleach and during detection of fluorescence recovery, and increased ≈5,000-fold during the 10- to 20-ms bleach pulse. Emitted fluorescence was filtered by a 530-nm interference filter, detected by a photomultiplier, and digitized by a 14-bit analog-to-digital converter. The photomultiplier was transiently gated off during the bleach pulse by reducing the voltage of the second dynode. Fluorescence was sampled over 1 s before the bleach pulse and then at rates up to 1 MHz during fluorescence recovery. Recovery half-time (t1/2), defined as the time when fluorescence recovered by 50% because of diffusion, was determined from fluorescence recovery curves, F(t), by using the equation: F(t) = Fo + [Fo + R (Finf − Fo)] (t/t1/2)/[1 + (t/t1/2)], where Fo is prebleach fluorescence, Finf is fluorescence at infinite time, and R is the fractional fluorescence recovery. Absolute diffusion coefficients (D) were determined by comparing t1/2 measured in gland fluid to that in similar size droplets of saline containing 10 mg/ml FITC-dextran with known diffusion coefficient of 8.0 × 10−7 cm2/s.

Results

Freshly excised fragments of human airways were mounted in a warmed, humidified perfusion chamber for measurement of the composition and viscosity of freshly secreted fluid from submucosal glands as shown in Fig. 1A. After drying the mucosal surface with a nitrogen stream, the mucosa was covered with a thin layer of oil to visualize gland secretions as they accumulated. Individual droplets (volume generally 0.1–0.5 μl) were microinjected with small volumes of solutions containing [Na+], [Cl−], pH, or viscosity-sensitive fluorescent dyes. The properties of single droplets were then studied by fluorescence microscopy. Fig. 1B shows a field containing several droplets of fresh gland secretions, some of which were microinjected with BCECF-dextran (Left, brightfield; Right, fluorescence). The fluorescent dyes distributed uniformly throughout the droplets in a few minutes as seen in Fig. 1B (Right).

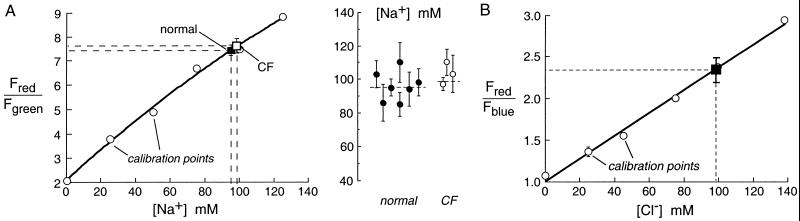

[Na+] was measured in individual droplets microinjected with 200 nm-diameter fluorescent polystyrene beads containing the red-fluorescing, Na+ sensitive dye Sodium Red and the green-fluorescing Na+-insensitive dye BODIPY-fl. The ratio of red-to-green fluorescence of the droplets (Fred/Fgreen) provided a quantitative measure of [Na+] that did not depend on pH or the concentrations of K+ or other cations/anions in the solution. Fig. 2A (Left) shows a solution calibration of Fred/Fgreen (open circles) together with averaged data in bronchi from seven normal (filled square) and three CF (open square) humans. For each human sample, [Na+] was measured in 5–10 individual droplets. Fig. 2A (Right) shows results from each human sample, where error bars represent standard errors determined from measurements on 5–10 different secretion droplets. [Na+] was not significantly different in gland secretions from normal vs. CF humans. [Na+] did not differ significantly in droplets judged qualitatively to be in the top vs. bottom one-third in size of all droplets measured.

Figure 2.

Salt concentration in fluid secreted from submucosal glands measured by using ratioable sodium- and chloride-sensitive fluorescent indicators. (A) [Na+] in freshly secreted fluid droplets from submucosal glands. Bronchial fragments were prepared as described in Methods, and secreted fluid droplets were microinjected with Kreb's buffer containing [Na+]-sensitive fluorescent beads. Bead red-to-green fluorescence ratios (Fred/Fgreen) vs. [Na+] were measured in isotonic aqueous solutions (choline replacing Na+; ○) and in gland secretions from normal (■) and CF (□) airways. (Right) [Na+] in samples from different individuals, each representing the average (mean ± SE) of 5–10 measurements on different gland droplets. (B) Chloride concentration in freshly secreted fluid droplets from submucosal glands. Droplets were microinjected with a fluorescent chloride-sensitive dextran. Bead red-to-blue fluorescence ratios (Fred/Fblue) vs. [Cl−] were measured in isotonic aqueous solutions (NO replacing Cl−; ○) and in gland secretions from normal airways (■).

replacing Cl−; ○) and in gland secretions from normal airways (■).

Similar ratiometric measurements were done to determine [Cl−] in gland secretions from normal human airways. The indicator consisted of a dextran conjugated with a blue-fluorescing Cl−-sensitive quinolinium dye and the red-fluorescing Cl−-insensitive dye tetramethylrhodamine. The ratio of red-to-blue fluorescence Fred/Fblue provided a quantitative measure of [Cl−] that does not depend on pH or solution anion/cation content. However, the measurement of droplet [Cl−] was more challenging than measurement of droplet [Na+] because of the need to subtract autofluorescence background from fluid droplets; background correction was not required for [Na+] measurements because background fluorescence was <1% for both the green and red signals. For this reason and because of the limited number of CF airway specimens, [Cl−] was measured only in samples from normal humans. Fig. 2B shows Fred/Fblue for the Cl−-sensitive fluorescent dextran in solution calibrations (open circles) and in the gland secretions (filled square). Gland fluid [Cl−] was similar to [Na+].

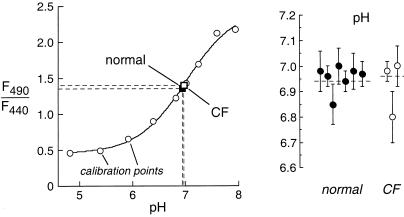

Measurements of pH in gland fluid secretions were done by microinjection of the pH indicator BCECF dextran, where the ratio of fluorescence excited at 490 and 440 nm (F490/F440) gives pH with excellent accuracy in the pH range 6.5–7.5. Fig. 3 (Left) shows F490/F440 for calibrations done in physiological solutions titrated to different pH (open circles) together with averaged results for gland secretions from normal (filled square) and CF (open square) human airways. Gland fluid pH from individual droplets remained stable for >10 min, indicating constant CO2/HCO content. Fig. 3 (Right) gives pH values measured in different human samples; each value representing the average of measurements from 5–12 droplets. Gland fluid pH was not significantly different in normal vs. CF human airways.

content. Fig. 3 (Right) gives pH values measured in different human samples; each value representing the average of measurements from 5–12 droplets. Gland fluid pH was not significantly different in normal vs. CF human airways.

Figure 3.

pH in fluid secreted from submucosal glands measured by using a ratioable fluorescent pH indicator. Secreted fluid droplets from bronchi were microinjected with Kreb's buffer containing 10 mg/ml BCECF-dextran. Ratios of BCECF-dextran fluorescence at 490 and 440 nm excitation wavelengths (F490/F440) measured in isotonic buffers of specified pH (○) and in gland secretions from normal (■) and CF (□) airways. (Right) pH in samples from different individuals, each representing the average of 5–12 measurements (mean ± SE) on different gland droplets.

Table 1 compares [Na+], [Cl−] and pH in gland secretions and the ASL of normal human bronchi. The values in ASL of unstimulated normal human bronchi were reported previously (25); the data in Table 1 include two additional sets of measurements from the same tissues used to measure gland fluid properties. There was no significant difference in [Na+], [Cl−], and pH measured in fresh gland secretions vs. the ASL.

Table 1.

Salt concentration and pH in the ASL and uncontaminated fresh submucosal gland secretions from bronchi of normal humans

| [Na+] mM | [Cl−] mM | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASL | 105 ± 4 (n = 5) | 92 ± 4 (n = 3) | 6.81 ± 0.20 (n = 9) |

| Gland fluid secretion | 94 ± 8 (n = 7) | 92 ± 12 (n = 2) | 6.97 ± 0.06 (n = 7) |

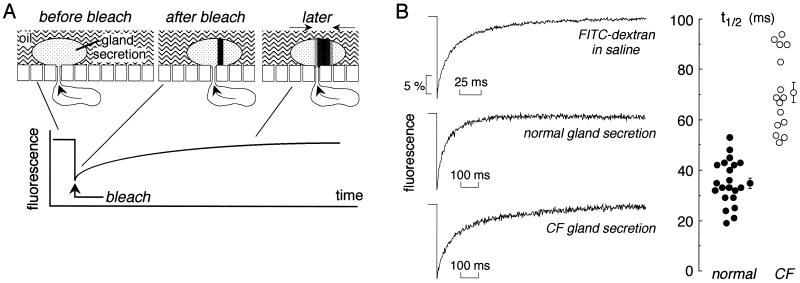

Last, apparent aqueous-phase viscosities were compared in fresh gland secretions microinjected with a 10,000-Da FITC-dextran by using the photobleaching recovery method. As depicted in Fig. 4A, a brief intense laser pulse irreversibly bleached fluorophores in a region defined as a thin vertical cylinder within the fluid droplet. Unbleached fluorophores from outside of the bleached region then move into the bleached region by diffusion, resulting in fluorescence recovery. The rate of fluorescence recovery provides a quantitative measure of FITC-dextran diffusion and thus of fluid viscosity. For determination of diffusion coefficient (D, cm2/s), recovery curves were compared for FITC-dextran dissolved at dilute concentration in saline, defined as having a relative viscosity of unity. Fig. 4B (Left, top curve) shows the fluorescence recovery of a small droplet of saline containing FITC-dextran, with a fitted half-time (t1/2, see Methods) of 13 ± 1.4 ms. The t1/2 was independent of droplet size (1- to 2-mm diameter) and was the same when measured in solution layers (FITC-dextran in saline sandwiched between coverglasses) of thicknesses 10–40 μm. Therefore, as predicted for the low magnification, low numerical objective lens used for this study, recovery curves are independent of droplet size and geometry.

Figure 4.

Viscosity of fluid secreted from submucosal glands measured by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. (A) Schematic of bleach geometry showing the bleaching of a ≈4-μm diameter vertical cylinder through the FITC-dextran-stained fluid droplet. Fluorescence increases as unbleached dye moves into the bleached area. See text for further explanation. (B Left) Representative photobleaching recovery curves for FITC-dextran in saline and in secreted fluid droplets from normal and CF human airways. (B Right) Fitted half-times (t1/2) for fluorescence recovery in individual fluid droplets from three different normal and two different CF samples. Averaged t1/2 and SE also shown. See text for computed diffusion coefficients.

Fig. 4B (Left) shows representative fluorescence recovery curves for FITC-dextran diffusion in secreted fluid droplets from normal and CF human airways. Fluorescence recovered nearly completely in both samples, but the recovery rate was visibly slower in the CF sample. Fig. 4B (Right) summarizes t1/2 values measured in three different normal and two different CF samples, each value corresponding to a single secreted droplet. Measurements from a third CF sample were excluded because of questionable tissue appearance and a very slow gland secretion rate. Computed diffusion coefficients were: 2.9 ± 0.3 × 10−7 cm2/s (normal) and 1.5 ± 0.1 × 10−7 cm2/s (CF). FITC-dextran diffusion was thus slowed to an approximate 2.7 ± 0.3-fold in gland fluid from normal airways compared to saline, and further slowed to an approximate 5.5 ± 0.6-fold in gland fluid from CF airways (P < 0.001).

Discussion

These studies apply minimally invasive quantitative procedures to measure [Na+], [Cl−], pH and viscosity in freshly secreted fluid from airway submucosal glands. In situ measurement of fluid composition and rheology avoids the trauma and potential alteration of fluid properties by microcapillary or other sampling methods. For example, it is difficult to maintain CO2/HCO /pH during sample manipulation, and fluid rheology can be markedly changed. We found that gland fluid salt concentration was similar to that of the ASL, that pH was in the range 6.8–7.0 in gland fluid and in the ASL, and that neither [Na+] nor pH differed significantly in gland fluid from CF airways. Diffusion measurements by a photobleaching method indicated that apparent viscosity in gland fluid from normal airways was 2.7-fold greater than that of saline, and further increased by 2-fold in gland fluid from CF airways.

/pH during sample manipulation, and fluid rheology can be markedly changed. We found that gland fluid salt concentration was similar to that of the ASL, that pH was in the range 6.8–7.0 in gland fluid and in the ASL, and that neither [Na+] nor pH differed significantly in gland fluid from CF airways. Diffusion measurements by a photobleaching method indicated that apparent viscosity in gland fluid from normal airways was 2.7-fold greater than that of saline, and further increased by 2-fold in gland fluid from CF airways.

The sampling of freshly secreted fluid from airway submucosal glands in vivo was first done by Nadel and coworkers (28) to study the regulation of gland fluid secretion by autonomic agonists. Microcapillary fluid sampling and microrheometry indicated that autonomic agonists regulated the viscoelastic properties of submucosal gland secretions from cat trachea (29). A modified protocol was used by Quinton (30) to show that gland secretions in freshly excised cat trachea are approximately isotonic. More recently, Ballard and coworkers have studied the role of submucosal gland secretions in fluid homeostasis in freshly excised proximal airways from pigs. Pretreatment of distal bronchi with Cl− and HCO transport inhibitors resulted in ductal mucus accumulation (31, 32), suggesting that inhibition of gland salt and water secretion leads to mucus obstruction of submucosal gland ducts, one of the early pathological findings in CF airways (33, 34). Pretreatment of tracheas with CFTR inhibitors supported a role of CFTR in glandular Cl− and HCO

transport inhibitors resulted in ductal mucus accumulation (31, 32), suggesting that inhibition of gland salt and water secretion leads to mucus obstruction of submucosal gland ducts, one of the early pathological findings in CF airways (33, 34). Pretreatment of tracheas with CFTR inhibitors supported a role of CFTR in glandular Cl− and HCO secretion (10). It is thus believed that fluid secretion by submucosal glands is a major contributor to establish the ion and water composition and volume of ASL (35). The absence of watery secretions from submucosal glands in CF could reduce ASL volume and hence mucociliary clearance by mechanisms including increased viscosity, altered macromolecule composition, and altered tonicity.

secretion (10). It is thus believed that fluid secretion by submucosal glands is a major contributor to establish the ion and water composition and volume of ASL (35). The absence of watery secretions from submucosal glands in CF could reduce ASL volume and hence mucociliary clearance by mechanisms including increased viscosity, altered macromolecule composition, and altered tonicity.

The measurements of ionic composition indicated that [Na+] and [Cl−] in freshly secreted gland fluid are in the range 90–105 mM and that pH is 6.8–7.0, predicting a [HCO ] of 6–8 mM. Although the concentrations of K+ and other solutes/macromolecules were not measured, it is clear from the data here that the secreted gland fluid differs significantly from bath values. In particular, gland secretions are more acidic than bath fluid, a point made long ago for ferret tracheal secretions (36). Because the mucosal surface was covered with oil and measurements were made soon after fluid was secreted, the values are not likely to be influenced by surface epithelial cells which make contact with a portion of the droplet surface. However, the fluid may well be modified by the epithelium lining the collecting and ciliated ducts within the gland. The ionic composition of glandular secretions was reported previously in cat trachea in which [Na+], [Cl−], and [K+] were found to be essentially equivalent to bath values (30). In nasal fluid collected after gustatory stimulation, which involves nasal submucosal gland secretion, Knowles et al. (30) reported [Na+] and [Cl−] each was ≈100 mM and not different between normal and CF subjects.

] of 6–8 mM. Although the concentrations of K+ and other solutes/macromolecules were not measured, it is clear from the data here that the secreted gland fluid differs significantly from bath values. In particular, gland secretions are more acidic than bath fluid, a point made long ago for ferret tracheal secretions (36). Because the mucosal surface was covered with oil and measurements were made soon after fluid was secreted, the values are not likely to be influenced by surface epithelial cells which make contact with a portion of the droplet surface. However, the fluid may well be modified by the epithelium lining the collecting and ciliated ducts within the gland. The ionic composition of glandular secretions was reported previously in cat trachea in which [Na+], [Cl−], and [K+] were found to be essentially equivalent to bath values (30). In nasal fluid collected after gustatory stimulation, which involves nasal submucosal gland secretion, Knowles et al. (30) reported [Na+] and [Cl−] each was ≈100 mM and not different between normal and CF subjects.

It was subsequently postulated that the properties of secreted fluid might be altered in CF (22). Based on short-circuit current measurements and inhibitor studies in pig trachea showing that CFTR may be involved in Cl− and HCO transport, it was proposed that the pH might be more acidic in gland secretions in CF (10). Our results indicate that neither [Na+] nor pH differed significantly in gland fluid from CF airways. However, because the measurements used only cholinergic stimulation and given other caveats mentioned below, we cannot conclusively rule out the possibility of abnormal Cl−, HCO

transport, it was proposed that the pH might be more acidic in gland secretions in CF (10). Our results indicate that neither [Na+] nor pH differed significantly in gland fluid from CF airways. However, because the measurements used only cholinergic stimulation and given other caveats mentioned below, we cannot conclusively rule out the possibility of abnormal Cl−, HCO , or fluid transport in cystic fibrosis glands.

, or fluid transport in cystic fibrosis glands.

Although gland fluid [Na+] and pH did not differ in CF, the viscosity of secreted gland fluid as measured by FITC-dextran diffusion was significantly elevated by ≈2-fold in CF vs. normal airways. The photobleaching methods and data analysis procedures for these measurements have been used extensively by our laboratory for the analysis of solute and macromolecule diffusion in cytoplasm and intracellular organelles (27, 38–40). It should be noted that FITC-dextran diffusion represents linear Newtonian diffusion and does not contain information about complex and dynamic viscous properties of mucus such as thixotropy, elasticity, and adhesivity (41). We noted empirically during microinjections that secretions in CF airways were more sticky than those in normal airways, suggesting differences in nonlinear viscous properties as well.

The elevated viscosity of CF gland mucus may represent increased mucin content, secondary to reduced fluid secretion because of loss of CFTR-mediated serous cell secretion (10, 12) or because of increased macromolecular secretion, either as a primary defect (42) or secondary to mucous cell hyperplasia. In any case, the increased viscosity of CF submucosal gland mucus might impair mucociliary clearance and antimicrobial defense mechanisms, thus contributing to bacterial colonization.

In these experiments, we did not study gland secretions induced by cAMP-elevating agents nor did we quantify rates of fluid accumulation, gland size, or gland structure. In contrast to the consistent and robust gland secretions in response to cholinergic stimulation, we found inconsistent secretions in response to adrenergic stimulation in the available human airway specimens, precluding analysis of secreted fluid properties. Based on reported data (43), submucosal glands in individuals with CF are expected to show hypertrophy and other morphological abnormalities, which would confound the interpretation of absolute fluid secretion rates from individual glands. However the intrinsic properties of gland mucus (salt content, pH, and viscosity) have been proposed to be the clinically relevant quantities. Notwithstanding these caveats, our results provide evidence against altered electrolyte content in uncontaminated CF gland mucus and suggest that the principal alteration in CF airway submucosal gland secretions is increased viscosity. Measurements of gland fluid properties in response to other types of stimulation are needed to test the generality of these conclusions. Measurements in vivo may be possible using the optical methods reported here.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. L. Vetrivel and L. V. Galietta at University of California, San Francisco, for their helpful suggestions, Drs. R. Robbins, R. Whyte, and G. Berry at Stanford University Medical Center for providing human bronchial samples, and Dr. Zhenjun Diwu at Molecular Probes for synthesis of Sodium Red. This work was supported by Grants HL60288, DK51817, HL59198, DK35124, and DK43840 from the National Institutes of Health and RDP Grant R613 from the National Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Abbreviations

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- ASL

airway surface liquid

- BCECF

2′,7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxy fluorescein

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Boucher R C. J Physiol (London) 1999;516:631–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0631u.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsui H, Grubb B R, Tarran R, Randell S H, Gatzy J T, Davis C W, Boucher R C. Cell. 1998;95:1005–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilewski J M, Frizzell R A. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:S215–S255. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.S215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith J J, Travis S M, Greenberg E P, Welsh M J. Cell. 1996;85:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wine J J. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:309–312. doi: 10.1172/JCI6222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basbaum C B, Madison J B, Sommerhoff C P, Brown J K, Finkbeiner W E. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:S141–S144. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.3_Pt_2.S141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basbaum C B, Jany B, Finkbeiner W B. Annu Rev Physiol. 1990;52:97–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basbaum C B, Ueki I, Brezina L, Nadel J A. Cell Tissue Res. 1981;220:481–498. doi: 10.1007/BF00216752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whimster W F. Appl Pathol. 1986;4:24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard S T, Trout L, Bebok Z, Sorscher E J, Crews A. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L694–L699. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.4.L694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkbeiner W E, Shen B-Q, Widdicombe J H. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:L206–L210. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.2.L206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang C, Finkbeiner W E, Widdicombe J H, Miller S S. J Physiol (London) 1997;501:637–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.637bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frigeri A, Gropper M, Turck C W, Verkman A S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4328–4331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King L S, Nielsen S, Agre P. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1541–C1548. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funaki H, Yamamoto F H, Koyama Y, Kondo D, Yaoita E, Kawasaki K, Kobayashi H, Sawaguchi S, Abe H, Kihara I. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C1151–C1157. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.4.C1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelhardt J F, Yankaskas J R, Ernst S A, Yang Y, Marino C R, Boucher R C, Cohn J A, Wilson J M. Nat Genet. 1992;2:240–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1192-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacguot J, Puchelle E, Hinnrasky J, Fuchey C, Bettinger C, Spilmont C, Bonnet N, Dieterle A, Dreyer D, Pavirani A, et al. Eur Respir J. 1993;6:169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oppenheimer E H, Esterly J R. Perspect Pediatr Pathol. 1975;2:241–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sturgess J, Imrie J. Am J Pathol. 1982;106:303–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwyer T M, Farley J M. Life Sci. 1991;48:2119–2121. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90144-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaya M, Finkbeiner W E, Widdicombe J H. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:L491–L494. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.261.6.L491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinton P M. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:6–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.1.8111599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Min G L, Wigley C, Zeng W, Noel L E, Marino C R, Thomas P J, Muallem S. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3414–3421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith J J, Welsh M J. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1148–1153. doi: 10.1172/JCI115696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jayaraman S, Song Y, Vetrivel L, Shankar L, Verkman A S. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:317–324. doi: 10.1172/JCI11154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verkman A S, Vetrivel L, Haggie P. In: Methods in Cellular Imaging. Periasamy A, editor. London: Oxford Univ. Press; 2001. , in press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kao H P, Verkman A S. Biophys Chem. 1996;59:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueki I, German V F, Nadel J A. Am Res Respir Dis. 1980;121:351–357. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leikauf G D, Ueki I F, Nadel J A. J Appl Physiol. 1984;56:426–430. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.56.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinton P M. Nature (London) 1979;279:551–552. doi: 10.1038/279551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trout L, Gatzy J T, Ballard S T. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L258–L263. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.2.L258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trout L, Gatzy J T, Ballard S T. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L1095–L1099. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inglis S K, Corboz M R, Taylor A E, Ballard S T. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L203–L210. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.2.L203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inglis S K, Corboz M R, Ballard S T. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L762–L766. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.5.L762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Widdicombe J H, Widdicombe J G. Respir Physiol. 1995;99:3–12. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)00095-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson N P, Kyle H, Webber S E, Widdicombe J G. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:2129–2135. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.5.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knowles M R, Robinson J M, Wood R E, Pue C A, Menta W M, Wager G C, Gatzy J T, Boucher R C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;100:2588–2595. doi: 10.1172/JCI119802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seksek O, Biwersi J, Verkman A S. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:131–142. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Partikian A, Ölveczky B, Swaminathan R, Li Y, Verkman A S. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:821–829. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukacs G, Haggie P, Seksek O, Lechardeur D, Freedman N, Verkman A S. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1625–1629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King M, Rubin B K. In: Airway Secretion: Physiological Bases for the Control of Mucus Hypersecretion. Takishima T, Shimura S, editors. New York: Dekker; 1994. pp. 283–314. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merten M D, Figarella C. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L93–L99. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.2.L93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bedrossian C W, Greenberg SD, Singer D B, Hansen J J, Rosenberg S H. Hum Pathol. 1976;7:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(76)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]