Abstract

Objectives

Little is known about the impact of diet on the oral microbiota of infants although diet is known to affect the gut microbiota. The aims of the present study were to compare the oral microbiota in breastfed and formula-fed infants, and investigate growth inhibition of streptococci by infant-isolated lactobacilli.

Subjects and Methods

207 mothers consented to participation of their three-month old infants. 146 (70.5%) infants were exclusively and 38 (18.4%) partially breastfed, and 23 (11.1%) were exclusively formula-fed. Saliva from all infants was cultured for Lactobacillus species, with isolate identifications from 21 infants. Lactobacillus isolates were tested for their ability to supress Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis. Oral swabs from 73 infants were analysed by the Human Oral Microbe Identification Microarray (HOMIM) and by q-PCR for Lactobacilius gasseri.

Results

Lactobacilli were cultured from 27.8% of exclusively and partially breastfed infants, but not from formula-fed infants. The prevalence of 14 HOMIM detected taxa, and total salivary lactobacilli counts differed by feeding method. Multivariate modelling of HOMIM detected bacteria and possible confounders clustered samples from breastfed infants separately from formula-fed infants. The microbiota of breastfed infants differed based on vaginal or C-section delivery. Isolates of Lactobacillus plantarum, L. gasseri and Lactobacillus vaginalis inhibited growth of the cariogenic S. mutans and the commensal S. sanguinis: L. plantarum > L. gasseri > L. vaginalis.

Conclusion

The microbiota of the mouth differs between breastfed and formula-fed three-month-old infants. Possible mechanisms for microbial differences observed include species suppression by lactobacilli indigenous to breast milk.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, microbiota, oral, lactobacilli. Lactobacillus gasseri

INTRODUCTION

The microbiota in the oral cavity and other parts of the gastro-intestinal (GI) tract develops from sterility at birth into the most heavily colonized parts of the human body. Different environmental conditions lead to distinct bacterial communities at the different anatomical niches), with over 700 taxa identified in the mouth and 700 taxa identified in the colon with minimal species overlap between the two sites, and significantly fewer taxa detected in the small intestine (1–4).

Establishment of stable bacterial ecosystems in the GI tract, including the mouth, evolves during a period of microbial variation chiefly during the first two years of life (1, 4–6). In general, initial colonizers of facultatively anaerobic genera, such as streptococci and actinomyces, are succeeded by more strictly anaerobic genera, such as bifidobacteria in the gut and veillonellae in the mouth (4–9). Molecular based studies have facilitated simultaneous detection of multiple bacterial species within the human microbiome, and findings suggest that changes during the period of variability and the final composition of the gut flora are related to negative health outcomes, such as allergy, obesity and intestinal diseases in childhood (10–13), and myocardial infarction in adults (14). There are fewer studies examining the outcomes of early microbial colonization in the mouth, but early acquisition of the cariogenic species Streptococcus mutans was associated with increased risk of dental caries (15).

The sources of bacteria transmitted to infants during the period of microbial variation include the mother’s vaginal, gut and oral microbiota, the skin of caretakers and siblings, and breast milk and other foods. Microbial colonization of the gut is influenced both by delivery method and early feeding practices (4). Two recent publications report that the oral microbiota also differs by mode of delivery with detection of Slackia exigua only in caesarean section delivered infants (16, 17), and by delayed establishment of Streptococcus mutans in vaginally compared with caesarian section delivered infants (18). There is little information, however, about the impact of breastfeeding on the composition of the oral microbiota, though studies focusing on a limited number of taxa support the concept that breastfeeding can affect early bacterial colonization in the mouth, consistent with reports for the gut (19,20).

Breast milk provides nutrition for the infant and is a source of lactobacilli, bifidobacteria and streptococci (21, 22). Further, breast milk components inhibit growth and attachment of bacteria, such as the caries pathogen S. mutans (23–25), but promote attachment of other Streptococcus and Actinomyces species (Johansson et al., unpublished data). Therefore, breast milk likely affects establishment of the microbiota in the mouth as well as in the gut.

The aim of the present study was to compare the oral microbiota in 3-month-old breastfed and formula-fed infants using the 16S rRNA probe Human Oral Microbe Identification Microarray (HOMIM, 26) and q-PCR to Lactobacillus gasseri. Total viable lactobacilli in the infant saliva were also compared between feeding groups, and the inhibitory capacity of isolated lactobacilli on growth of selected Streptococcus species was examined as a possible model of bacterial modulation of species colonization.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study group

The present study used a previously described cohort of 3-month-old infants (n=207) (16). Information on feeding mode of the infant (exclusive or partial breast feeding, or exclusive formula feeding), mode of delivery, gestational age at birth and other possible confounders, such as infant health (allergy, infections, stomach discomfort), use of antibiotics or products containing probiotic bacteria, use of pacifier and presence of teeth was obtained by a questionnaire. Information on infant body weight and length at birth and at three months of age and use of antibiotics at delivery was obtained from child health care and medical records. Oral samples were obtained from the infants at three months of age, between 1–3 hours after the latest meal (mean 2 hours) by an experienced dentist (PLH) at a neighbourhood Dental Clinic. The study was approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board, Umeå, Sweden, and participating mothers signed informed consent at recruitment.

Oral microbiota by 16S rDNA probes in HOMIM microarray

The mucosa of the cheeks, the tongue and alveolar ridges of the infants were swabbed carefully using sterile cotton swabs (Applimed SA, Chatel-St-Denis, Switzerland). This mucosa-adherent biofilm was immediately transferred to Eppendorf tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) with 200 μl TE-buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.6), and stored at −80°C.

DNA was purified from samples from 55 breastfed infants (out of 184) that were randomly selected after stratification by mode of delivery and from 23 (all available) formula-fed infants as described (16). The DNA yield was 60–1,220 ng DNA. Five samples were excluded due to low DNA yield leaving 52 samples from breastfed infants (44 exclusively and 8 partially breastfed) and 21 samples from formula-fed infants for microarray analysis.

Purified DNA was assayed using 422 oligonucleotide probes to the 16S rRNA gene targeting more than 300 bacterial taxa in the HOMIM microarray (http://mim.forsyth.org/) and by quantitative PCR (q-PCR) to Lactobacillus gasseri (27). Samples were analysed at the HOMIM microarray facility at The Forsyth Institute, Cambridge MA as previously described (26). Hybridization signals were read on a six level scale (0–5) with a lower limit of detection of approximately 104 cells (28).

Selective culture of salivary lactobacilli and characterization of isolates

Approximately 1 mL of whole saliva was collected into ice-chilled test tubes, transported and cultured as described (16). Saliva samples from all infants (n=207) were plated on Rogosa agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany; 29) for Lactobacillus counts and on blood agar (Columbia base agar, supplemented with 5% horse blood) for total viable counts. The plates were incubated anaerobically for 48–72 h. Counts were expressed as CFU/mL saliva.

For the last 21 infants sampled with cultivable Lactobacillus in saliva, on average six colonies were subcultured for identification. Isolates were characterized and typed by colony morphology, RFLP pattern and carbohydrate fermentation tests (API 50 CH system, BioMérieux SA, Marcy-l ‘Etoile, France). Twenty-four isolates with differing characteristics were identified by comparing 16S rRNA gene sequences with the databases HOMD (http://www.homd.org) and NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

RFLP

A 1,420 bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers 16S-LF and 16S-R (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′and 5′-GGG CGG TGT GTA CAA GGC-3′, respectively) (30). Briefly, a 5 μL bacteria suspension in Milli-Q water (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was mixed with 25 μL HotStarTaq Mastermix (Qiagen, Hamburg, Germany), 16μL Milli-Q water and 20 pmol of the16S-LF and 16S-R primers in a total volume of 50 μl. The thermal cycling conditions were: 15 min at 95°C; 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 59°C, 1.5 min at 72°C; followed by 10 min at 72°C. An aliquot (10μL) of the16S PCR product was digested for 1.5 h at 37°C using the enzymes HinfI and MslI (New England BioLabs Inc., Ipswich, MA) in a total volume of 15 μL. The digest was applied on a 4% TBE (Tris/Borate/EDTA) NuSieve 3:1 agarose gel (Lonza, Rockland, ME) and products were visualized by UV-light after ethidium bromide staining.

16S rDNA sequencing

Aliquots of the 16S rDNA PCR products were purified and sequenced (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebensberg, Germany), and sequences were compared with HOMD (http://www.homd.org) and NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) databases.

qPCR detection of L. gasseri

qPCR for L. gasseri was performed as described by Byun et al. (27) on DNA extracted from 190 of the mucosal swab samples, including samples from 63 infants with microarray data. The q-PCR standard curve reaction mixture for L. gasseri contained a total volume of 20 μL, consisting of Roche (Atlanta, GA) SYBR Green master mix 2X (10 μL), 20uM of each primer (0.25 μL), PCR grade water (5.5 μL), and L. gasseri ATCC 29601 genomic DNA ranging from 2.5 ng/μL to 2.5 fg/μL (4 μL). The q-PCR conditions were an initial denaturation of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 59°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s and generated a 322-bp amplicon. Amplification and detection of DNA was performed using a Roche Lightcycler 480.

Growth inhibition by isolate Lactobacillus species

The ability to inhibit growth of S. mutans (strains Ingbritt and NG8) and Streptococcus sanguinis (strain SK162) was tested for one randomly selected infant isolate each of Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus vaginalis, and L. gasseri (identified by 16S rRNA gene sequences), and corresponding type strains (L. plantarum CCUG30503, L. vaginalis CCUG31452, L. gasseri CCUG31451 (CCUG, University of Göteborg, Sweden) in an agar overlay method using De Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MSR) agar (pH 5.0; Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) in the bottom layer and M17 agar (pH 7.2; Fluka) in the top layer (31). Inhibition was tested for lactobacilli concentrations from 103 to 109 CFU/mL. L. reuteri ATCC55730 (BioGaia, Stockholm, Sweden), previously shown to inhibit S. mutans growth (32), was used as a positive control and agar plates without lactobacilli were a negative control. Growth after inhibition was scored as 0 = no visible colonies (complete inhibition), 1 = slightly reduced growth, or 2 = no growth inhibition (31). All experiments were done in triplicate and repeated three times.

Statistics

Data handling and statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS version 18 software. Numbers of lactobacilli in saliva were logarithmically transformed to improve normality. Other measures were acceptably normal distributed. Bacterial counts, and length and weight at birth and at three months were averaged among infants by feeding method. Differences between means were tested using ANOVA or Student’s t-test. Data from the microarray were analysed as detected (all signal levels ≥ 1) or not-detected (score 0) by child. Differences in prevalence distribution between groups were tested with a Chi2 test. Odds ratios to have a species/cluster detected in the microarray were estimated by logistic regression, with the possible confounder mode-of-delivery included as a covariate. Adjusting for number of teeth (three formula feed infants had one to three erupting lower incisors) did not affect results further (data not shown). Differences for descriptive data are considered statistically significant for p< 0.01. The False Discovery Rate (33) was used to identify a p-value accounting for multiple comparisons in the microarray. Thus, p<0.005 was considered statistically significant for comparisons of the prevalence by microarray.

Multivariate partial least squares analysis (PLS) when three groups or partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) when two groups modelling (SIMCA P+, version 12.0, Umetrics AB, Umeå, Sweden) was performed as previously described (34, 35). In contrast to traditional regression models, PLS modelling, which defines the maximum separation between class members (here feeding method) in the data, is suitable for data where the number of observations is smaller than the number of variables, and where the X variables co-vary. Dichotomous HOMIM signals, and the selected individual characteristics, gender, weight and length at birth and three months, gestational weeks at delivery, delivery mode, age at screening in days, use of pacifier, and presence of teeth built the X-block, and mode of feeding the Y-block (outcome). Variables were autoscaled to unit variance, and cross-validated prediction of Y was calculated (36). Cross-validation was done by a systematic prediction of one 7th of the data by the remaining 6/7th of the data. The separation of subjects is displayed in a score loading plot and the importance of each x-variable by PLS loadings in a column plot. R2- and Q2-values give the capacity of the x-variables to explain (R2) and predict (Q2) the outcome.

Four different models were run: Model 1 all 73 HOMIM analysed samples (n=73, comprising exclusively breastfed, partially breastfed, and exclusively formula fed infants), Model 2 exclusively breast or formula-fed infants (n=65), Model 3 (n=35) and Model 4 (n=30) as Model 2 but restricted to vaginally and caesarean section delivered infants, respectively. The same model groups but restricted to infants born vaginally in or after gestational week 37 were also tested.

RESULTS

Cohort description

The study population comprised 207 infants of whom 146 (70.5 %) were exclusively breastfed, 38 (18.4%) partially breastfed, and 23 (11.1%) exclusively formula-fed at the time of the sampling visit. In accordance with the inclusion criteria, all infants were healthy. Two infants received antibiotics immediately after birth, and none thereafter. These two infants were not included in the microarray sub-group. Except for vitamin D supplement (recommended for all infants) no child had received any medication. Approximately half of the mothers who had delivered by caesarean section with an acute complication had received intravenous antibiotics, but none of the mothers who delivered infants vaginally had antibiotics at delivery. None of the infants had been given products (including infant formula) with probiotics.

Among all infants (n=207), there were no differences between infants grouped by mode of feeding in gender, length and weight at birth and at three months of age, mode of delivery (80.2 % were delivered vaginally), or being full term (98% were born in gestational week 37–42 and two infants were born in gestational week 35 (both exclusively breastfed) (Table 1) Although not statistically significant, exclusively formula-fed infants were on average 17 days older than breastfed infants at time of sampling. Among the children with samples analyzed by microarray, the proportion vaginally delivered infants was lower among breastfed than formula-fed infants. This was taken into account in the statistical analyses.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participating three-months-old infants by feeding mode.

| All study infants | Feeding mode at three months of age

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exclusively breastfed (n=146) | Partly breastfed (n=38) | Exclusively formula feed (n=23) | p-value | |

| Gender (% boys)1 | 50.0 | 39.5 | 47.8 | 0.512 |

| Age in months (mean (range))2 | 3.5 (2.4–5.5) | 3.7 (2.4–5.3) | 3.9 (2.8–5.1) | 0.468 |

| Vaginal delivery (% positive)1 | 82.2 | 76.3 | 73.9 | 0.523 |

| Weight (gram)2 | ||||

| at birth | 3,504 (3,414–3,594) | 3,486 (3,279–3,694) | 3,549 (3,299–3,800) | 0.913 |

| at 3 months of age | 6,177 (6,045–6,309) | 6,043 (5,770–6,316) | 6,738 (5,706–6,369) | 0.548 |

| Length (cm)2 | ||||

| at birth | 50.2 (49.8–50.6) | 49.9 (49.1–50.7) | 50.0 (49.0–51.0) | 0.741 |

| at 3 months of age | 60.8 (60.3–61.2) | 60.7 (59.9–61.6) | 60.8 (59.8–61,9) | 0.993 |

| Microbiology at 3 months of age | ||||

| Total viable count (mean and range ×1010)2 | 7.54 (7.47–7.61) | 7.55 (7.39–7.72) | 7.59 (7.39–7.78) | 0.879 |

| Total viable Lactobacillus count (% positive saliva samples)1 | 32.4 | 27.0 | 0.0 | 0.006 |

| L. gasseri by qPCR (% positive swab samples)1 | 23.03 | 38.94 | 13.35 | 0.080 |

| HOMIM selected infants (n) | n=44 | n=8 | n=21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% boys)1 | 56.0 | 25.0 | 47.6 | 0.487 |

| Age in months (mean (range))2 | 3.4 (3.2–3.5) | 3.4 (2.7–3.9) | 3.7 (3.5–4.0) | 0.07 |

| Vaginal delivery (% positive)1 | 43.2 | 0.0 | 76.2 | 0.001 |

| Weight (gram)2 | ||||

| at birth | 3,480 (3,284–3,677) | 3,256 (2,642–3,870) | 3,633 (3,392–3,873) | 0.337 |

| at 3 month of age | 6,259 (5,998–6,540) | 5,787 (5,080–6,494) | 6,054 (5,699–6,401) | 0.308 |

| Length (cm)2 | ||||

| at birth | 50.3 (49.4–51.1) | 49.5 (46.3–50.7) | 50.2 (49.2–51.2) | 0,202 |

| at 3 month of age | 60.5 (59.7–61.3) | 59.7 (57.3–62.1) | 61.0 (59.9–62.1) | 0.506 |

| Microbiology at 3 months of age | ||||

| Total viable count (mean and range ×10×10)2 | 7.55 (7.42–7.68) | 7.91 (7.53–8.30) | 7.63 (7.43–7.83) | 0.09 |

| Total viable Lactobacillus count (% positive saliva samples)1 | 27.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0016 |

| L. gasseri by qPCR (% positive swab samples)1 | 19.57 | 37.58 | 14.39 | 0.2076 |

Differences between group numbers tested with Chi2 test.

Differences between group means tested with ANOVA (three groups) or t-test (two groups). If not stated otherwise data are presented as mean with 95% CI. Total bacteria are expressed as log10 values.

139/146 samples analysed

36/38 samples analysed

15/23 samples analysed

One-sided test based on the association in all infants.

41/44 samples analysed

8/8 samples analysed

14/21 samples analysed

As described earlier no significant differences were observed between the 207 participating infants and those infants whose mother declined to participate (16).

Saliva culture data

Saliva was evaluated for cultivable lactobacilli and total viable counts from all breastfed and formula fed infants (n=207). Viable Lactobacillus species were detected in saliva from 32.4 % and 27.0 % of fully and partially breastfed infants, respectively, but in none of the formula-fed infants (Table 1). Geometric means for infants with detectable lactobacilli (fully and partially breastfed infants, respectively) were 7,990 and 1,862 CFU/mL saliva, and medians (max-min) 7,450 (44–1,490,000) and 800 (100–72,000) CFU/mL saliva, respectively (p=0.005). In breastfed infants, the number of colony forming units of lactobacilli per mL saliva correlated inversely with age in days (r=−0.447, p=0.003).

Among the 24 isolates (from 21 infants) with differing RFLP and API50 patterns, and 1 420 bp 16S rDNA sequences, L. gasseri was most prevalent (87.5 % of all isolates), but L. plantarum (2 colonies), and L. vaginalis (1 colony) were also identified.

qPCR detection of L. gasseri

L. gasseri was detected in 25.3% of the oral swabs using qPCR (Table 1) including 63.0% mucosal swab samples that were positive for Lactobacillus species by selective culture of saliva (p=0.000). The odds ratio of detecting L. gasseri by qPCR in oral swabs if culture positive for lactotobacilli in saliva was 7.98 (95% CI 3.82–16.70, p=0.000). When stratified by feeding method, 23.0% of fully and 38.9% of partially breastfed, and 13.3% of formula fed infants were positive for L. gasseri by qPCR (Table 1). Similar proportions of samples were L. gasseri positive by qPCR in the subset of samples analysed by microarray data only (Table 1).

HOMIM microarray detected bacteria and clustering of infants by feeding mode

Bacterial profiles of 52 exclusively or partly breastfed, and 21 formula-fed infants were analysed. Overall, 81 bacterial species and 12 bacterial clusters (probes detecting three or more closely related species) in seven phyla or divisions were detected by the HOMIM microarray in oral biofilms of three-month old infants (online-only supplemental Table S1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A168 [Detection frequency {%} of taxa identified by HOMIM in exclusively formula or exclusively breast-fed, 3-month-old infants. Taxa are identified by species name or by their Human Oral Taxon {HOT; www.homd.org} number if unnamed, or by cluster group. Clusters are indicated by superscript numbers with targeted taxa in the footnote.]). Streptococcus Cluster III, Streptococcus anginosus/intermedius, Streptococcus oralis/Streptococcus sp. HOT 064, Streptococcus parasanguinis I and II, Gemella haemolysans, and Veillonella atypica/parvula were detected in over 90% of samples, while other species were detected in low prevalence. The mean number of species/clusters detected per sample was 22 with a range of 10 to 41. The correlation between number of positive species/clusters and age was 0.259 (p=0.038).

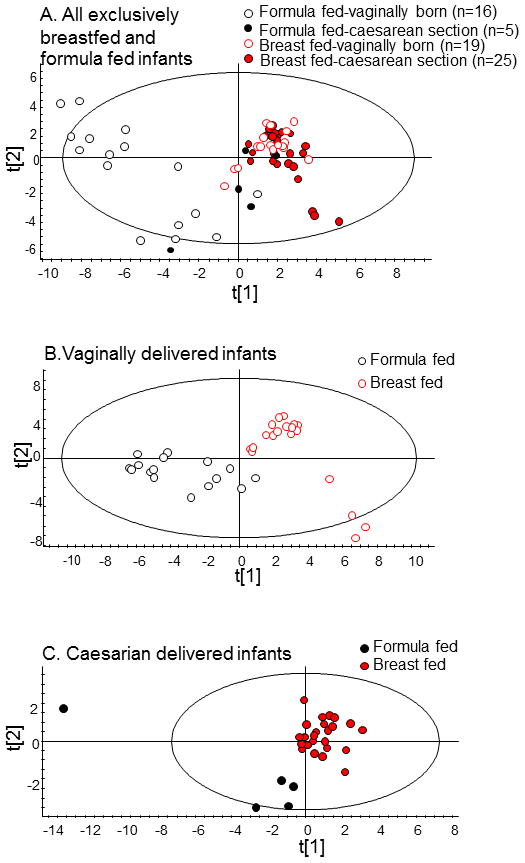

Data from the 73 infants were clustered using multivariate PLS modelling with feeding mode as outcome, and dichotomized HOMIM microarray signals, salivary lactobacilli, and individual characteristics (see statistics section) for the x-variable block (Model 1). This produced a model with one significant component and an explanatory and predictive capacity of 62.0 % (R2=0.620) and 55.7 % (Q2=0.557), respectively. Samples from exclusively breastfed infants clustered separately from exclusively formula-fed infants, whereas partially breastfed infants were interspersed among the breastfed and formula-fed clusters (data not shown). Restricting analysis to exclusively breastfed and exclusively formula-fed infants (Model 2, n=65) virtually separated the two different exclusive feeding method groups by their oral microbiota (Fig. 1A). Further analyses were restricted to comparisons of the oral microbiota of exclusively breastfed (n=44) and exclusively formula-fed infants (n=21) (Models 2–4).

FIGURE 1. PLS-DA score scatter plots illustrating clustering of exclusively breastfed (red symbols) compared with exclusively formula fed (black symbols) three-month old infants by oral microbiota.

Clustering was derived by multivariate PLS modelling using dichotomous HOMIM microarray signals, lactobacilli cultured from saliva, and selected individual characteristics as the X- block and mode of feeding as the Y-block. (A) Model 2 (all 65 exclusively breast- and formula-fed infant samples used for HOMIM microarray), (B) Model 3 (samples from vaginally delivered infants used for HOMIM microarray), and (C) Model 4 (samples from caesarean section delivered infants used for HOMIM microarray). Red symbols with unfilled circles indicate vaginally and filled dots caesarean delivered infants. Black symbols with unfilled circles indicate vaginally and filled dots caesarean delivered infants.

Species diversity in breastfed compared with formula-fed infants

By the microarray 79 species/clusters were detected in oral samples of exclusively breastfed infants compared with 68 species/clusters from formula-fed infants (p=0.071). Of the 93 species/clusters detected, 25 were detected only in breastfed infants, compared with 14 species/clusters that were detected only in formula-fed infants (online-only supplemental Fig. S1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A173 [Bilateral bar chart of the detection frequency (%) among 3-month-old exclusively breast-fed or exclusively formula-fed infants. To illustrate the difference between feeding mode, probes to bacterial species are ordered by order of reactivity detection in breastfed infants with taxa detected more frequently in breast-fed to the top and more frequently in formula-fed infants below. Taxa are identified by species, by their Human Oral Taxon (HOT) number if unnamed, or by cluster group {see supplemental Table S1 for detailed information}].). However, the mean number of species detected by child was higher in formula than breastfed fed infants (mean 27 (range 16–35 versus mean 21 (range 10 to 41)); p<0.005). The mean number of detected species by child was also higher in formula-fed infants after stratifying for mode of delivery (data not shown).

Microbiota in breastfed compared with formula-fed infants

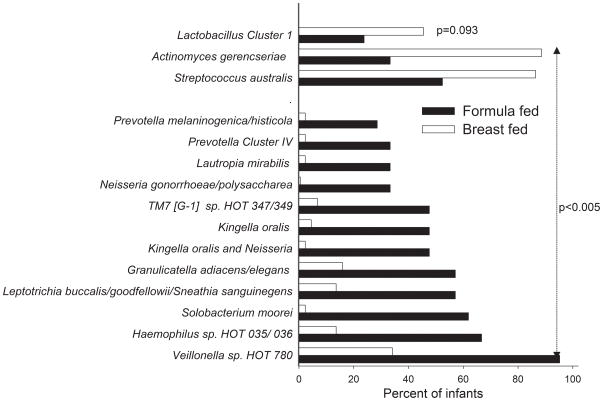

Data from 14 probes (13 species and one cluster) differed significantly between exclusively breastfed and formula-fed infants when results from the χ2 test (p<0.005) was combined with the results from the logistic regression adjusted for mode of delivery (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Major taxa differing between breastfed and formula-fed infants.

The figure illustrates HOMIM detection frequency of 13 bacterial species and 1 cluster that differed by the false discovery rate determined p-value<0.005 and logistic regression including mode of delivery as a covariate. Prevalence of Lactobacillus Cluster I is also shown.

Actinomyces gerencseriae and Streptococcus australis were detected more frequently in exclusively breastfed compared with formula-fed infants. Prevotella melaninogenica/ histicola and Prevotella Cluster IV, Lautropia mirabilis, Neisseria gonorrhoea/ polysaccharea, TM7[G-1] sp. HOT 347/349, Kingella oralis, Kingella and Neisseria species, Granulicatella adiacens/elegans, Leptotrichia buccalis/goodfellowii/Sneathia sanguinegens, Solobacterium moorei, Haemophilus sp. HOT 035/036, and Veillonella HOT 180 were detected more frequently in formula-fed infants.

Streptococcus australis was detected more frequently in breastfed than formula fed infants regardless of delivery mode (Table S1, http://links.lww.com/MPG/A168). Prevalence of Solobacterium moorei,Leptotrichia buccalis/goodfellowii/Sneathia sanguinegens, and Haemophilus sp. HOT 035/036 was higher in formula fed infants regardless of delivery mode. The detection frequency of Granulicatella elegans, however, differed between delivery groups with a higher prevalence among caesarean delivered breastfed infants, but a higher prevalence in vaginally delivered formula fed infants.

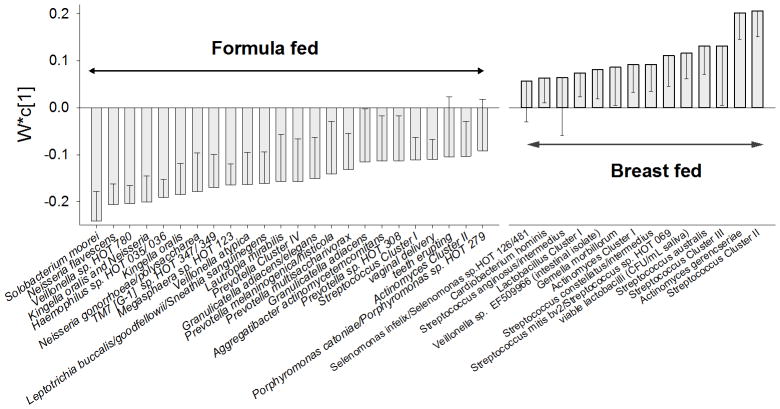

PLS-DA modelling on mode of feeding in exclusively breast- and formula-fed infants (Model 2, n=65) rendered a model with two significant components, and explanatory and predictive capacities of 74.3 % (R2=0.743) and 59.8 % (Q2=0.598) (Fig. 1A, Fig. 3). Similarly, PLS-DA modelling on mode of feeding in vaginally delivered infants (Model 3; n=35) rendered a strong model (R2=0.837, Q2=0.717), which completely separated breastfed from formula-fed infants (Fig. 1B). The PLS-DA model on mode of feeding in caesarean section delivered infants (Model 4; n=30) was weaker (R2=0.401, Q2=0.185, Fig. 1C). Models 2 and 3, involving the two infants born before gestational week 37, remained stable when infants born before gestational week 37 were excluded.

FIGURE 3. Taxa and some infant characteristics that differed between formula and breast-fed infants (Model 2) by PLS-modelling.

The figure illustrates mean loadings with measurement error (95% confidence interval) in a PLS derived column loading plot for exclusively breast- versus formula-fed infants. The underlying PLS model employed all bacterial taxa detected by microarray and potential confounders (see statistics section) simultaneously. Variables with highest loading in each group are displayed, and variables where the confidence interval does not pass 0 (zero) are statistically significant.

For both Model 2 and 3, PLS-DA, which detects latent structures in the data swarm, confirmed the taxa that were significantly more prevalent in breastfed infants by Chi2-testing and logistic regression, including cultivable lactobacilli. Model 2 (both vaginally and caesarean section delivered infants) also revealed a breast-feeding association with Streptococcus cluster II and III, Streptococcus mitis bv 2/ Streptococcus sp. HOT 069, Streptococcus constellatus/intermedius, Actinomyces Cluster I, Gemella morbillorum, Veillonella sp. EF509966 (intestinal isolate), Lactobacillus Cluster 1, and Cardiobacterium hominis, and Model 3 (vaginally delivered infants only) the addition of Streptococcus anginosus/intermedius, Eubacterium yurii, Catonella morbi/Catonella sp. HOT 164, Prevotella Cluster I, Prevotella loescheii/Prevotella sp. HOT 472 and Capnocytophaga granulosa/Capnocytophaga sp. HOT 326 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of bacteria associations with breastfeeding and formula feeding in univariate Chi2 testing (Fig. 3) and PLS modelling loading scores (for Model 2 see Fig. 3). All PLS models employ the same y and x variables. Model 2 comprises exclusively breastfed and exclusively formula fed infants (n=65), Model 3 (n=35) and Model 4 (n=30) are as Model 2 but restricted to vaginally and caesarean section delivered infants, respectively.

| Species | Chi2-test1 | Association with breastfeeding PLS-DA modelling |

Species | Chi2-test1 | Association with formula feeding PLS-DA modelling |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

| Streptococcus Cluster II | + | + | + | Streptococcus Cluster I | + | + | |||

| Streptococcus Cluster III | + | + | + | Streptococcus cristatus | + | ||||

| Streptococcus anginosus/intermedius | + | Gemella haemolysans | + | ||||||

| Streptococcus australis | + | + | + | Granulicatella adiacens/elegans | + | + | + | ||

| Streptococcus constellatus/intermedius | + | + | Granulicatella adiacens | + | + | ||||

| Streptococcus mitis bv 2/ Streptococcus sp. HOT 069 | + | + | Granulicatella elegans | + | |||||

| Gemella morbillorum | + | Megasphaera sp. HOT 123 | + | + | + | ||||

| Lactobacilli by cultivation | + | + | + | + | Solobacterium moorei | + | + | + | |

| Lactobacillus Cluster I (microarray) | + | Veillonella atypical/parvula | + | ||||||

| Eubacterium yurii | + | Veillonella atypical | + | + | + | ||||

| Catonella morbi/Catonella sp. HOT 164 | + | Veillonella parvula | + | ||||||

| Veillonella sp. EF5099662 | + | Veillonella sp. HOT 780 | + | + | + | ||||

| Actinomyces Cluster I | + | + | Actinomyces Cluster II | + | + | ||||

| Actinomyces gerencseriae | + | + | + | Leptotrichia buccalis/goodfellowii/ Sneathia sanguinegens | + | + | + | ||

| Slackia exigua | + | Prevotella Cluster IV | + | + | + | ||||

| Prevotella Cluster I | + | Prevotella melaninogenica/histicola | + | + | |||||

| Prevotella loescheii/Prevotella sp. HOT 472 | + | Prevotella multisaccharivorax | + | + | + | ||||

| Capnocytophaga granulosa/ Capnocytophaga sp. HOT 326 | + | Prevotella sp. HOT 308 | + | + | |||||

| Cardiobacterium hominis | + | + | Kingella oralis | + | + | + | |||

| Kingella oralis and Neisseria | + | + | + | ||||||

| Neisseria flavescens | + | + | + | ||||||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae/polysaccharea | + | + | + | ||||||

| Lautropia mirabilis | + | + | + | ||||||

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | + | + | |||||||

| Haemophilus sp. HOT 035/036 | + | + | + | ||||||

| Campylobacter concisus/rectus | + | ||||||||

| TM7 [G-1] sp. HOT 347/349 | + | + | + | ||||||

Differences where p<0.005 are indicated.

Intestinal isolate

Similarly for both Model 2 and 3, PLS-DA confirmed taxa that were significantly more prevalent in formula-fed infants by univariate testing. Model 2 also revealed a formula-feeding association with Streptococcus Cluster I, Granulicatella adiacens, Actinomyces Cluster II, Prevotella sp. HOT 308 and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and in Model 3 the addition of Streptococcus cristatus, Gemella haemolysans, Granulicatella elegans, Veillonella atypical/parvula, and Veillonella parvula (Table 2).

Model 4 of caesarean section delivered infants (n=30) indicated that cultivable lactobacilli in saliva and Slackia exigua were significantly associated with being breast-fed, whereas Campylobacter concisus/rectus was associated with being formula-fed.

The PLS score scatter plot from Model 2 showed distinct clusters (Fig. 1A) based on feeding and delivery methods. The groups of (i) breast-fed, vaginally born infants; (ii) breast-fed, caesarean section born infants; and (iii) 8 of the formula-fed, vaginally delivered infants each formed distinct clusters. The remaining formula-fed infants clustered with groups (iii) and (ii).

Comparing microarray data and qPCR data, no statistically significant association was found between microarray detection of Lactobacillus Cluster I and detection of L. gasseri by qPCR (p=0.107). Overall samples from 82% of the infants were negative for both Lactobacillus Cluster I and L. gasseri by qPCR, whereas 39% infants were positive for both Lactobacillus tests.

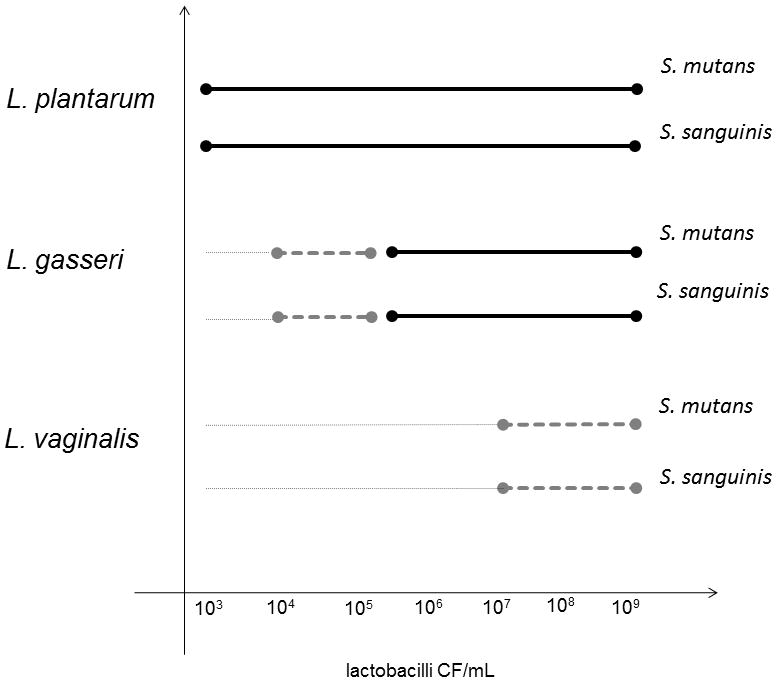

Saliva lactobacilli from breastfed infants with inhibitory growth effects against streptococci

Isolates of the three identified Lactobacillus species (L. gasseri, L. plantarum, and L. vaginalis) inhibited growth of S. mutans (strains Ingbritt and NG8) and S. sanguinis (strain SK162) (Fig. 4). L. plantarum exhibited the strongest growth inhibition, followed by L. gasseri and then L. vaginalis. L. plantarum totally inhibited growth at the lowest concentration of lactobacilli (103 CFU/mL), whereas L. gasseri did so at concentrations ≥ 105 CFU/mL. L. vaginalis had no effect at concentrations ≤ 105 CFU/mL and only partial inhibition effect at lactobacilli concentrations ≥ 107.

FIGURE 4. Growth inhibition by lactobacilli.

Growth of Streptococcus mutans (strains Ingbritt and NG8) and Streptococcus sanguinis (strain SK162) when exposed to increasing numbers of lactobacilli isolated from three-months-old infants. Type strains gave identical results (data not shown).

●–––––● completely inhibited growth (score 0), ●– – – –● partially inhibited growth (score 1), and ...........no effect on growth (score 2).

DISCUSSION

In our investigation of the oral microbiota in three month-old infants we sought differences associated with feeding method. We observed that microbial colonization patterns clustered breastfed infants separately from formula-fed infants. We further found that lactobacilli that inhibited growth of selected streptococci were cultured only in saliva from breastfed infants.

In the present study, 93 species or species clusters out of the approximately 300 taxa evaluated by the HOMIM microarray were detected in the three month-old infants. The most prevalent species belonged to the phylum Firmicutes/Bacilli (genera Streptococcus and Gemella) and Firmicutes/Clostridia (genus Veillonella). Considering the detection threshold of about 104 cells for the HOMIM microarray, species detected by the assay most likely represent bacteria colonizing the mouth of the infants, rather than transient cells (26, 37). Previous studies using bacterial culture have shown that oral bacterial colonization in the neonate starts with streptococci from the viridians group (7, 38), whereas significant colonization by anaerobes was not detected before two months of age (7). The present frequent detection of species in Firmicutes phylum, and particularly within the genus Streptococcus, is consistent with these reports, as is detection of various anaerobes in lower frequencies in three month-old infants (8, 38).

L. gasseri was the most prevalent species detected among the 24 isolates from selective culture of saliva that were characterized by RFLP, sugar fermentation profile, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. L. gasseri was not detected in the microarray analysis of mucosal swab samples of the L. gasseri qPCR positive infants, despite a validate probe being included in the microarray. This difference likely reflected in part the increased sensitivity of the qPCR assay compared with the microarray assay, and in part that different samples were analysed. In contrast, lactobacilli in Cluster I (L. casei, L. paracasei, L. rhamnosus) were detected in microarray-analyzed mucosal swabs. Since the microarray can be less sensitive than selective culture and most infants had less than 104 CFU/ml saliva of lactobacilli, qPCR was performed to evaluate if the difference between saliva and microarray detection was due to method sensitivity or sample origin. qPCR confirmed that L. gasseri were present in mucosal swabs, and that infants with salivary lactobacilli were 5 times more likely to have L. gasseri detected in the mucosal swabs.

The current data set is characterized by a larger number of variables than subjects, and by the presence of species that might be interdependent based on shared environmental needs or inter-species co-aggregation. Under these conditions the multivariate PLS method is suitable to search for subject clustering and identifying the variables characterizing the clusters.

The distribution of gender, weight and length at birth and 3 months, number of siblings and total salivary bacterial counts did not differ between infants selected for microarray analysis compared with all infants sampled. The major difference between breastfed and formula-fed infants used for microarray analysis was that formula-fed infants were on average 17 days older, and that the prevalence of caesarean section, and the associated prevalence of complicated deliveries requiring use of intravenous antibiotics, was higher in breastfed infants. This inbalance was due to randomization after stratification for delivery mode among the breastfed infants, whereas all formula fed infants were included to reach highest possible power. Intravenous use of antibiotics at delivery was previously shown to be non-influential on the oral microbiota at three months of age (16). Further, the PLS results from vaginally delivered infants were consistent with results from all infants. We, therefore, consider the groups of breastfed and formula-fed infants suitable for PLS analysis, and the power trustworthy to discriminate between infants fed breast milk from those fed formula. However, confirmation of the results is needed, especially to exclude a possible systematic effect on presence of anaerobic species due to the slightly higher age in formula fed infants, and the possibility of an unrevealed confounding by mode of delivery. In fact, the borderline significant correlation between age and mean number of species/clusters detected per child in the present study suggests that age may contribute to higher mean number of species/clusters detected per child in formula feed infants.

Previously, the mode of delivery was found to affect the oral microbiota in infants at three (16) and six to ten months of age (17), but any biological significance of the different colonization patterns remains unproven (17). The present study indicates that at three months of age, and presumably later, the major impact of mode of delivery is in breastfed infants. In the present analyses, infants being breast- or formula-fed and delivered by caesarean section were not separated in the PLS scatter plot. Although PLS theoretically allows modelling of very few subjects, as in the subgroup formula-fed infants delivered by caesarean section (n=5), results from the analyses separating out that group must be considered preliminary as we cannot distinguish how representative these five infants are for the group they represent. Hence, the results from this explorative study should be validated in an independent cohort, and mechanisms for observed effects explored.

In the first few months of life the major influences on the establishment and succession of bacteria in the mouth comes from person-to-person transmission, composition of the infant’s saliva, and microbial cross talk (1, 5, 39), besides the presently shown effect of mode of feeding. Exposure to the mother’s vaginal flora is considered to explain a greater diversity in the gut microbiota of vaginally born infants compared to those delivered by caesarean section (1, 4, 6, 39), consistent with our recent report for the oral microbiota (16). In the present study, breastfed infants had fewer species/clusters detected per child, whereas within the group of breastfed infants there were slightly more species/clusters found than among formula fed infants. However, to evaluate a possible mechanism of the difference in species distribution between feeding groups we observed that the microbiota of breast-fed infants compared with formula-fed infants included Streptococcus Cluster I and II species (by prevalence) and Lactobacillus species (from PLS modelling), both genera that include health associated species (40, 41). In contrast, the biofilms of formula-fed infants included more anaerobic species usually associated with gingival inflammation (42) but not lactobacilli by culture of saliva. While our observed detection of lactobacilli associated with breast-feeding is a novel and preliminary observation, the finding is supported by findings in another ongoing study in four month-old infants where viable lactobacilli are detected in saliva from approximately one third of breastfed infants but not in formula-fed infants. Possible mechanisms by which human milk affects the oral microbiota in early infancy include an interplay between milk receptors for protein-protein or lectin interactions with bacterial adhesins, innate immunity and immunoglobulin effects, and inter-species interactions by milk bacteria such as lactobacilli, bifidobacteria and streptococci.

While there is limited information on mechanisms for initial establishment of lactobacilli in the mouth of infants and the role of breast-milk as a source of oral bacteria (21, 22), culturing lactobacilli only from breastfed infants, and q-PCR detection of L. gasseri in breastfed infants, in the current study is consistent with detection of lactobacilli in breast milk (43) and their transmission from the nipple and from milk (21, 22, 44). The finding that only a fraction of breastfed infants have viable lactobacilli in saliva may reflect decreasing content of lactobacilli in milk by lactation age. Solis et al. (22) found that bacterial levels in breast-milk decreased from 105 CFU/mL at day 1 to 10–103.7 CFU/mL at three months, and West et al. (13) that lactobacilli were no longer detected in feces with increasing age in breastfed infants. This is in line with the present finding of a negative correlation between age in days and CFU lactobacilli per mL saliva. Another possible mechanism for differences in detection of lactobacilli may relate to avidity for lactobacilli to host receptors. Orally isolated lactobacilli adhere to saliva gp340 and mucins (45, 46). These glycoproteins are present in polymorphic variants in saliva, and at least for Streptococcus mutans adhesion to gp340 occurs in a polymorphism-dependent way (47).

Lactobacilli isolated from oral (31), breast milk (48) and other non-oral sites (31, 49) inhibit growth of selected oral pathogens especially cariogenic mutans streptococci and Candida albicans. Growth inhibition of such species could be a mechanism for beneficial oral bacteria biofilm modulation, but will require testing against health associated species, such as Streptococcus sanguinis (50). A recent report indicated that 12-weeks daily exposure to lactobacilli did not affect the oral biofilm bacterial ecology as determined by a checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization method (51). In the present study three Lactobacillus species L. plantarum, L. gasseri and L. vaginalis, isolated from the mouth of participating infants, inhibited growth of both S. mutans and S. sanguinis, demonstrating that the growth inhibitory capacity of oral lactobacilli in infants may not be specific to cariogenic (S. mutans) or health-associated (S. sanguinis) species. Prediction of the net effect of viable lactobacilli in saliva of breastfed infants and the contribution of lactobacilli to the microbial community of breastfed versus formula fed infants, as well as later in life, remains to be explored.

In conclusion, the present findings demonstrate that the observed differences in the gastrointestinal tract microbiota composition due to feeding mode extend to the oral cavity, and that viable lactobacilli detected in saliva from breastfed, but not formula-fed infants had an inhibitory effect on oral streptococci. A limitation of the present study is the low number of formula-fed infants, while a strength is the use of a microarray that facilitated simultaneous detection of a much greater number of oral taxa compared with culture methods, or single species or multiplex species-specific PCR. The finding that the oral microbiota differs between breastfed and formula-fed infants, with a potentially more health-associated oral flora in breast-fed infants indicates the value of prospective longitudinal studies where health outcomes, primarily early childhood caries but possibly also gut microflora and associated health conditions, are evaluated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from Västerbotten County Council, The Swedish Patent Revenue Foundation, and by a Public Health Service Grant DE-015847 (AT) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, USA, and Henning and Johan Throne-Holst’s Foundation (PLH). Agnetha Rönnlund and Christine Kressirer (qPCR) are acknowledged for skillful laboratory work.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jpgn.org).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contrerasc M, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11971–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science. 2009;326:1694–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1177486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Costello EK, Berg-Lyons D, Gonzalez A, Stombaugh J, Knights D, Gajer P, Ravel J, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R. Moving pictures of the human microbiome. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R50. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-r50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adlerberth I, Wold AE. Establishment of the gut microbiota in Western infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:229–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cephas KD, Kim J, Mathai RA, Barry KA, Dowd SE, Meline BS, Swanson KS. Comparative analysis of salivary bacterial microbiome diversity in edentulous infants and their mothers or primary care givers using pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108 (Supplement 1):4578–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Könönen E, Jousimies-Somer H, Bryk A, et al. Establishment of streptococci in the upper respiratory tract: longitudinal changes in the mouth and nasopharynx up to 2 years of age. J Dent Res. 2002;51:723–30. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-9-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Könönen E. Anaerobes in the upper respiratory tract in infancy. Anaerobe. 2005;11:131–36. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björkström MV, Hall L, Soderlund S, et al. Intestinal flora in very low-birth weight infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:1762–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luoto R, Kalliomaki M, Laitinen K, et al. Initial Dietary and Microbiological Environments Deviate in Normal-weight Compared to Overweight Children at 10 Years of Age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:90–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181f3457f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjögren YM, Jenmalm MC, Böttcher MF, et al. Altered early infant gut microbiota in children developing allergy up to 5 years of age. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:518–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West CE, Hammarström M-L, Hernell O. Probiotics during weaning reduce the incidence of eczema. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20:430–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koren O, Spor A, Felin J, et al. Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108 (Suppl 1):4592–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011383107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Straetemans MM, van Loveren C, de Soet JJ, et al. Colonization with mutans streptococci and lactobacilli and the caries experience of children after the age of five. J Dent Res. 1998;77:1851–5. doi: 10.1177/00220345980770101301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lif Holgerson P, Harnevik L, Hernell O, et al. Mode of birth delivery affects oral microbiota in infants. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1183–8. doi: 10.1177/0022034511418973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelun Barfod M, Magnusson K, Lexner MO, et al. Oral microflora in infants delivered vaginally and by caesarean section. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21:401–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Caufield PW, Dasanayake AP, et al. Mode of delivery and other maternal factors influence the acquisition of Streptococcus mutans in infants. J Dent Res. 2005;84:806–11. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hokama T, Hakamoto I, Takenaka S, et al. Throat microflora in breastfed and formula fed infants. J Trop Pediatr. 1999;42:324–6. doi: 10.1093/tropej/42.6.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadir T, Uygun B, Akyuz S. Prevalence of Candida species in Turkish children: relationship between dietary intake and carriage. Arch Oral Biology. 2005;50:33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martín R, Heilig GH, Zoetendal EG, et al. Diversity of the Lactobacillus group in breast milk and vagina of healthy women and potential role in the colonization of the infant gut. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;103:2638–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solís G, de Los Reyes-Gavilan CG, Fernández N, et al. Establishment and development of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria microbiota in breast-milk and the infant gut. Anaerobe. 2010;16:307–10. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aimutis WR. Bioactive properties of milk proteins with particular focus on anticariogenesis. J Nutr. 2004;134:989S–95S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.4.989S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wernersson J, Danielsson-Niemi L, Einarson S, et al. Effects of human milk on adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite in vitro. Caries Res. 2006;40:412–7. doi: 10.1159/000094287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danielsson Niemi L, Hernell O, Johansson I. Human milk compounds inhibiting adhesion of mutans streptococci to host ligand-coated hydroxyapatite in vitro. Caries Res. 2009;43:171–8. doi: 10.1159/000213888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE. Molecular microbial diagnosis. Periodontol. 2000–2009;51:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byun R, Nadkarni MA, Chhour KL, Martin FE, Jacques NA, Hunter N. Quantitative analysis of diverse Lactobacillus species present in advanced dental caries. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3128–36. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3128-3136.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colombo AP, Boches SK, Cotton SL, et al. Comparisons of subgingival microbial profiles of refractory periodontitis, severe periodontitis, and periodontal health using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1421–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogosa M, Mitchell JA, Wiseman RA. A selective medium for the isolation and enumeration of oral and fecal lactobacilli. J Bacteriol. 1951;62:132–3. doi: 10.1128/jb.62.1.132-133.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yavuz E, Gunes H, Bulut C, et al. RFLP of 16S-ITS rDNA region to differentiate lactobacilliat species level. World J Microbiol Biotech. 2004;20:535–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simark-Mattsson C, Emilson CG, Håkansson EG, et al. Lactobacillus-mediated interference of mutans streptococci in caries-free vs. caries-active subjects. Eur J Oral Sci. 2007;115:308–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasslöf P, Hedberg M, Twetman S, et al. Growth inhibition of oral mutans streptococci and candida by commercial probiotic lactobacilli -an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sjöström M, Wold S, Söderström B. PLS discriminant plots. In: Gelsema ES, Kanal LN, editors. Pattern Recognition in Practice II. Vol. 486 Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bylesjö M, Rantalainen M, Cloarec O, et al. OPLS discriminant analysis: combining the strengths of PLS-DA and SIMCA classification. J Chemometrics. 2006;20:341–51. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wold S. Cross validatory estimation of the number of components in factor and principal component models. Technometrics. 1978;20:397–405. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson JC, Cuff CF, Lukomski S, et al. Use of 16S ribosomal RNA gene analyses to characterize the bacterial signature associated with poor oral health in West Virginia. BMC Oral Health. 2011;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearce C, Bowden GH, Evans M, et al. Identification of pioneer viridans streptococci in the oral cavity of human neonates. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:67–72. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mändar R, Mikelsaar M. Transmission of mother’s microflora to the newborn at birth. Biol Neonate. 1996;69:30–5. doi: 10.1159/000244275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanasi E, Dewhirst FE, Chalmers NI, et al. Clonal analysis of the microbiota of severe early childhood caries. Caries Res. 2010;44:485–97. doi: 10.1159/000320158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnston BC, Goldenberg JZ, Vandvik PO, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD004827. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004827.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanner AC, Kent R, Jr, Kanasi E, et al. Clinical characteristics and microbiota of progressing slight chronic periodontitis in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:917–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jara S, Sánchez M, Vera R, et al. The inhibitory activity of Lactobacillus spp. isolated from breast milk on gastrointestinal pathogenic bacteria of nosocomial origin. Anaerobe. 2011;17:474–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Björksten B, Burman LG, De Chateau P, et al. Collecting and banking human milk:to heat or not to heat? Br Med J. 1980;281:765–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6243.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haukioja A, Yli-Knuuttila H, Loimaranta V, et al. Oral adhesion and survival of probiotic and other lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in vitro. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:326–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackenzie DA, Jeffers F, Parker ML, et al. Strain-specific diversity of mucus-binding proteins in the adhesion and aggregation properties of Lactobacillus reuteri. Microbiology. 2010;156:3368–78. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jonasson A, Eriksson C, Jenkinson HF, et al. Innate immunity glycoprotein gp-340 variants may modulate human susceptibility to dental caries. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olivares M, Díaz-Ropero MP, Martín R, Rodríguez JM, Xaus J. Antimicrobial potential of four Lactobacillus strains isolated from breast milk. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101:72–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stamatova I, Meurman JH. Probiotics: health benefits in the mouth. Am J Dent. 2009;22:329–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caufield P, Dasanayake A, Li Y, et al. Natural history of Streptococcus sanguinis in the oral cavity of infants: evidence for a discrete window of infectivity. Infect Immun. 2000;7:4018–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4018-4023.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sinkiewicz G, Cronholm S, Ljunggren L, et al. Influence of dietary supplementation with Lactobacillus reuteri on the oral flora of healthy subjects. Swed Dent J. 2010;34:197–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.