Abstract

In cardiac muscle, a number of posttranslational protein modifications can alter the function of the Ca2+ release channel of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), also known as the ryanodine receptor (RyR). During every heartbeat RyRs are activated by the Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release mechanism and contribute a large fraction of the Ca2+ required for contraction. Some of the posttranslational modifications of the RyR are known to affect its gating and Ca2+ sensitivity. Presently, research in a number of laboratories is focussed on RyR phosphorylation, both by PKA and CaMKII, or on RyR modifications caused by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS / RNS). Both classes of posttranslational modifications are thought to play important roles in the physiological regulation of channel activity, but are also known to provoke abnormal alterations during various diseases. Only recently it was realized that several types of posttranslational modifications are tightly connected and form synergistic (or antagonistic) feed-back loops resulting in additive and potentially detrimental downstream effects. This review summarizes recent findings on such posttranslational modifications, attempts to bridge molecular with cellular findings, and opens a perspective for future work trying to understand the ramifications of crosstalk in these multiple signaling pathways. Clarifying these complex interactions will be important in the development of novel therapeutic approaches, since this may form the foundation for the implementation of multi-pronged treatment regimes in the future.

Keywords: cardiac muscle, ryanodine receptor, calcium signaling, oxidation, nitrosation, cardiomyopathy, heart failure

1. Introduction

In cardiac muscle, ryanodine receptors (RyRs) serve as Ca2+ release channels of the intracellular Ca2+ store, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Thereby, they provide a large fraction of the Ca2+ required to initiate muscle contraction from beat to beat. They are normally activated by a small amount of Ca2+ entering into cardiac muscle cells from the extracellular space, via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. This Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) from the SR is the mechanism which amplifies the Ca2+ signal and governs excitation-contraction (EC) coupling by activation of RyRs (for review see [1]).

Research on the RyR, both on its structure and function, has been carried out over the last decades using multiple experimental approaches and techniques to overcome the difficulty of examining a channel that is located intracellularly and therefore not easily accessible. This includes assays using isolated SR vesicles (e.g. [2,3]), single RyR channels reconstituted into lipid bilayers (e.g. [4–9]), permeabilized cardiomyocytes [10,11], but also various biochemical techniques (e.g. see [12,13]). Cellular ultrastructural and co-localization information has been obtained with immunocytochemistry and electron tomography [14,15] and structure on the molecular level has been assessed with cryo-electron microscopy [16,17].

Many of these studies have confirmed the potential of RyRs to undergo several of the numerous known posttranslational modifications and a number of reports have provided evidence for functional consequences resulting from some of these modifications. These data were frequently obtained in artificial experimental systems and under conditions far away from the natural environment of the RyRs. Therefore, it often remained unclear whether and how these observations on or near the molecular level would translate into intact and living cardiomyocytes and into the entire organ or organism [18].

Some time ago it became practical to closely examine RyR function in-situ and within its native environment, which means inside living cells. This has become possible because of groundbreaking developments of technologies to faithfully image subcellular and microdomain Ca2+ signals with appropriate spatial and temporal resolution. These developments were significantly driven by the chemical synthesis of bright and kinetically fast fluorescent Ca2+ indicators [19,20] and the simultaneous advancements of laser-scanning confocal microscopy combined with digital image acquisition and processing [21].

Since several excellent reviews cover many aspects of RyR posttranslational modifications on the biochemical and molecular level [22–30], here we will concentrate mainly, but not exclusively, on recent findings that have been obtained by examining RyR activity and cardiac Ca2+ signaling on the cellular level, where the channels can be examined under conditions not far from their native environment. In particular, we will focus on the consequences of a combined impact of several posttranslational modifications and their mutual interactions during physiological regulation of RyRs and during the development of cardiac diseases affecting RyR function.

2. The ryanodine receptor

2.1. The RyR macromolecular complex

In mammals three RyR isoforms are known: the skeletal muscle form RyR1, the cardiac RyR2 and the more broadly expressed brain form RyR3. The cardiac RyR2 is a large macromolecular complex consisting of a homo-tetramer with 4 subunits comprising a molecular mass of 565 kDa each, totaling 2.2 MDa (for review see [31]). This complex is regulated and modulated in numerous ways by ions (e.g. Ca2+, Mg2+, H+), by small molecules (e.g. ATP, cADPR) and by proteins (e.g. sorcin, calstabin2, junctin, triadin). Important for this review, the macromolecular complex is also connected to protein kinase A (PKA), phosphatases (e.g. phosphatase 1 and 2A) and phosphodiesterase (PDE4D) which are tethered to the channel and held near their target sites by means of anchoring proteins [32,33]. This allows for a tight and spatially confined homeostatic regulation of the balance between PKA-dependent RyR phosphorylation and phosphatase dependent dephosphorylation. Ca2+/calmodulin dependent kinase II (CaMKII) was also found to be associated with the RyRs, but the nature and target specificity of this connection are less clear [34]. On the RyR itself, a number of phosphorylation sites have been identified (see chapter 3). Furthermore, the RyR complex comprises several free cysteines that can be subject to reversible oxidative modification (see chapter 4).

2.2. The Ca2+ signaling microdomain in the vicinity of the RyRs

In cardiac muscle, a large fraction of the RyRs are organized in dyads, where the SR membrane contains a cluster of 30–250 RyRs [35] and comes in close contact (gap of ~15 nm) with the T-tubular membrane, which harbors the voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels. Opening of one or more L-type channels can activate CICR via several RyRs within a cluster. The tiny SR Ca2+ release generated by these few opening channels gives rise to a Ca2+ spark, an elementary Ca2+ signaling event, which can be detected and analyzed using confocal imaging of Ca2+ sensitive fluorescence indicators (for reviews see [36,37]). During each heart beat, a large number of Ca2+ sparks is activated simultaneously, summing up to form the cardiac Ca2+ transient for the activation of contraction. Ca2+ sparks and even smaller Ca2+ release events, Ca2+ quarks, can also occur spontaneously, for example during diastole [38,39]. Spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ quarks are considered to occur accidentally and partly underlie the SR Ca2+ leak. Accidental spontaneous Ca2+ sparks do not normally trigger larger Ca2+ signals, such as Ca2+ waves, and are therefore not arrhythmogenic. Eventless or “quarky” SR Ca2+ release through single (or very few) RyRs was recently proposed to contribute substantially to the leak [38–42]. However, under conditions of SR Ca2+ overload and in circumstances which sensitize the RyRs, single Ca2+ sparks can initiate Ca2+ waves traveling along the myocytes in a saltatory fashion from sarcomere to sarcomere [43–46]. These Ca2+ waves have a substantial arrhythmogenic potential, since they are able to initiate Ca2+ activated currents, such as the Na+-Ca2+ exchange current (INCX), which in turn may depolarize the cardiomyocyte to generated a delayed afterpotential (DAD) and even trigger premature action potentials.

2.3. Ca2+ dependent activation and inactivation of the RyRs

The open probability of RyRs depends steeply on the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, whereby Ca2+ is thought to bind to the RyR activation site [47]. The increase of the RyR open probability subsequent to openings of L-type Ca2+ channels and entry of Ca2+ into the dyadic cleft is the main mechanism for activation of CICR during physiological activity. The Ca2+ concentration prevailing in the dyadic cleft can only be estimated with computer models at present [48], thus we use “Ca2+ sensitivity” of RyRs as a descriptive term. In any case, the Ca2+ sensitivity of the RyRs in-situ is low enough to ensure independent activation of adjacent Ca2+ spark sites, to allow for the regulation of cardiac Ca2+ signals by virtue of local control and recruitment of Ca2+ sparks. The Ca2+ sensitivity of the channels for this type of activation is known to depend on a number of modulators as mentioned above, but also on several regulatory or disease-associated posttranslational protein modifications (see chapters 3 and 4). Inactivation of the RyRs and termination of the Ca2+ sparks in-situ is less well understood and is the focus of significant ongoing research efforts. One proposed mechanism is based on regulation of the RyRs by the Ca2+ concentration inside the SR. Thereby, lowering the SR Ca2+ concentration during a spark would make the RyRs insensitive for Ca2+ on the cytosolic side of the channels, which causes their deactivation. Based on observations in SR vesicles, RyRs in lipid bilayers and cells overexpressing calsequestrin, deactivation has been suggested to occur via a retrograde signal mediated by allosteric interactions between calsequestrin (acting as the Ca2+ sensor) and junctin and/or triadin and the RyR [2,8,49,50]. This mode of spark termination could be stabilized by a reinforcing mechanism that has been proposed recently based on model predictions. The local SR depletion and subsequent decay in Ca2+ release flux from the SR during a Ca2+ spark may contribute to the self-termination, because of the resulting decline of the dyadic Ca2+ concentration [51]. Other proposed mechanisms for spark termination include Ca2+ dependent inactivation of the RyRs [52], but up to 100 µM cytosolic Ca2+ no RyR inactivation was observed in permeabilized cardiomyocytes [53]. Another mechanistically attractive possibility is stochastic attrition, where the probabilistic simultaneous closure of all RyRs in one cluster would interrupt their mutual activation by CICR within the dyadic cleft [54]. When all channels close, the very high dyadic Ca2+ concentration drops to low cytosolic levels within a few milliseconds [48]. However, the probability of all channels to be closed simultaneously is quite low given the estimated number of RyRs in a cluster [35], unless their gating is partly coupled [55].

The Ca2+ release termination mechanism mediated by lowering of the SR luminal Ca2+ concentration and deactivation of the RyRs could also be important under conditions of SR Ca2+ overload, the opposite of the depletion during a Ca2+ spark and CICR. By sensitizing the RyRs for Ca2+ on the cytosolic side, elevations of intra SR Ca2+ could initiate or facilitate store-overload induced Ca2+ release (SOICR) and arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves [46,56].

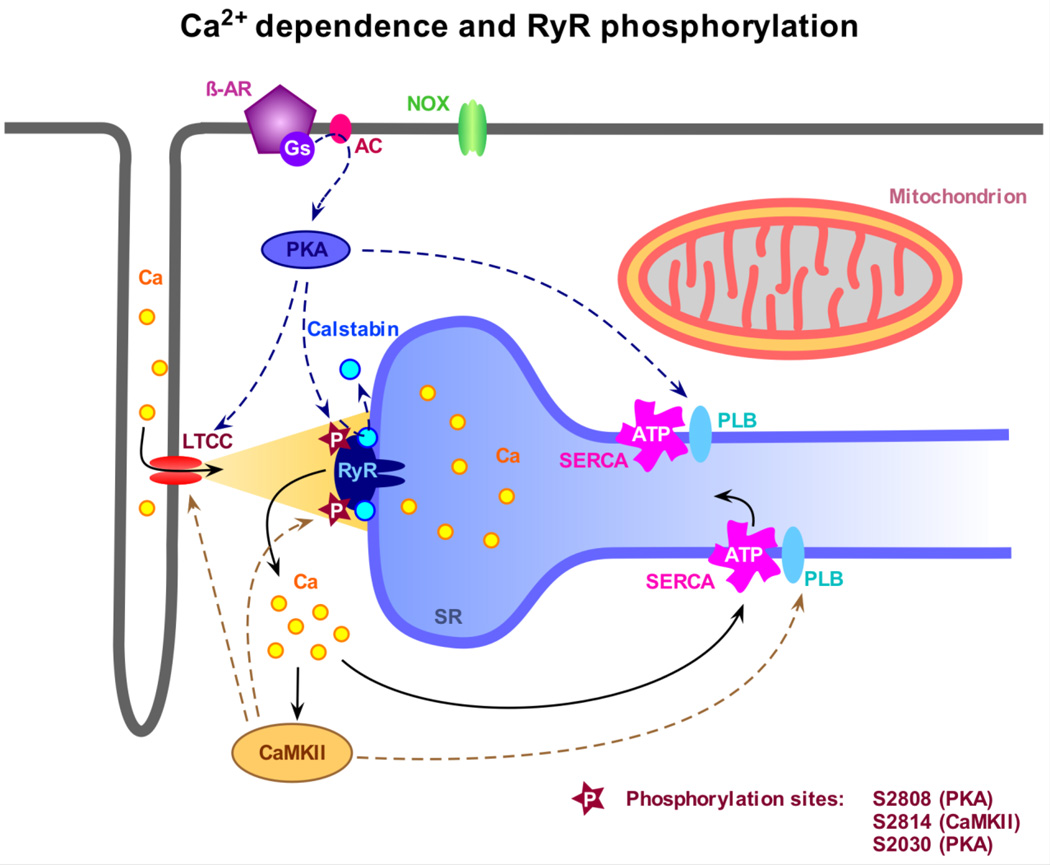

3. RyR phosphorylation

As mentioned above, the mechanism and functional consequences of RyR phosphorylation has attracted much recent attention. Fig. 1. shows a summary of the involved pathways. Interest in this issue was inspired by a report suggesting that PKA dependent “hyperphosphorylation” of RyRs could occur during heart failure (HF) thereby aggravating this condition. Hyperphosphorylation was proposed to promote the Ca2+ sensitivity of RyRs resulting in elevated open probability. This in turn would cause a substantial diastolic SR Ca2+ leak, which could contribute to low SR Ca2+ content, smaller Ca2+ transients and hence weak heart beat [12]. Using mainly biochemical and molecular biology approaches, serine 2808 and 2030 on the RyR have been identified as possible phosphorylation sites for protein kinase A (PKA), and serine 2814 for CaMKII. However, the specificity of these sites for the mentioned kinases remains a disputed issue [12,57–59] and additional sites are likely to exist [60]. Moreover, a fierce controversy revolves around the functional consequence and pathophysiological relevance of the phosphorylation at these sites [61,62]. This debate may result from differences in experimental approaches, methods and tools, but also from variations of the particular animal and disease models.

Fig. 1.

Modulation of the ryanodine receptor (RyR) by Ca2+ and phosphorylation. Ca2+ influx via the L-type Ca channel (LTCC) activates the RyR and triggers Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), a process referred to as Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release or CICR, leading to myocyte contraction. The levels of free cytosolic Ca2+ are tightly regulated by the SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) and the sarcolemmal Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (not indicated). After CICR and contraction, the Ca2+ store is refilled by pumping Ca2+ back into the SR thereby re-establishing diastolic Ca2+ levels. The sensitivity of RyR toward activating Ca2+ is modulated by phosphorylation. Stimulation of the β1-adrenoreceptor (β-AR) leads to Gs-protein-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase (AC) and further cAMP-dependent activation of PKA. PKA can directly phosphorylate RyR at several phosphorylation sites, presumably at S2808, possibly inducing dissociation of calstabin 2, and at S2030, but also modulates the LTCC and SERCA function, the latter by phosphorylation of phospholamban (PLB). Increased cytosolic Ca2+ levels activate CaMKII, which directly phosphorylates RyR at S2814. Similar to PKA, CaMKII also phosphorylates PLB and the LTCC leading to global changes in myocyte Ca2+ homeostasis.

3.1. Phosphorylation by CaMKII

The picture which emerges from the literature seems to be more clear for the consequences of CaMKII activation which leads to phosphorylation of serine 2814 on the RyR and possibly other sites [60,62], among many collateral targets. CaMKII activity seems to produce quite consistent functional changes of the RyRs that are reconcilable with the general prediction over a wide range of experimental settings and approaches, extending from single channel experiments to cellular Ca2+ signaling and a variety of transgenic animals. In single channel experiments the open probability of the RyRs was generally found to be increased upon phosphorylation by CaMKII [63] (but see [64,65]). In isolated cardiomyocytes activation of CaMKII was associated with an increase of the Ca2+ spark frequency [66]. Transgenic mice overexpressing the cardiac isoform of CaMKII showed a marked hypertrophy, altered expression and phosphorylation levels several proteins involved in Ca2+ signaling. Despite lower SR Ca2+ content, the cells also showed elevated Ca2+ spark frequencies, leading to pronounced SR Ca2+ leak and a susceptibility for arrhythmias [67,68]. Ablation of CaMKII resulted in a protection of the animals from cardiac hypertrophy, possibly mediated by the unavailability of CaMKII signaling in the pathways of excitation-transcription coupling [69,70]. To obtain further insight into the functional role of serine 2814 on the RyR several mouse models were engineered to specifically scrutinize this site. In one animal serine 2814 was replaced by an alanine, which removes its capability to become phosphorylated by CaMKII (S2814A mouse). Hearts of these animals and cardiomyocytes isolated from them showed blunted force-frequency relationships [71] and the mice were protected from arrhythmias induced by tachypacing after being subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) to induce hypertrophy and failure [72]. Conversely, the S2814D RyR, where serine is replaced by aspartic acid, mimics constitutive CaMKII dependent RyR phosphorylation and increases the open probability of the channels in bilayer experiments. Cardiomyocytes isolated from S2814D mice showed elevated Ca2+ spark frequencies that could not be further increased by CaMKII activation [72] and the mice developed a propensity for arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death when stressed with catecholaminergic challenges or tachypacing subsequent to TAC.

Taken together, these and numerous other studies draw a picture whereby in the short-term CaMKII dependent phosphorylation substantially modifies RyR function, cardiac Ca2+ signaling and EC-coupling. Overall, these signaling systems seem to become boosted, more active and Ca2+ sensitive but less well controlled, from the molecular to the cellular and organ level. Thus, CaMKII has been considered as a treatment target for multiple short term and long-term cardiac conditions that are associated with disturbances of Ca2+ signaling and CaMKII activation [73–76].

3.1. Phosphorylation by PKA

PKA dependent phosphorylation and “hyperphosphorylation” of the RyRs at serine 2808 during heart failure (and in a transgenic mouse model overexpressing the catalytic domain of PKA in the heart) has been proposed to dissociate the stabilizing protein calstabin 2 (a.k.a FKPB-12.6) from the RyR macromolecular complex, a sequence of events that is suggested to be followed by major functional changes of the channels resulting in diastolic Ca2+ leak, SR Ca2+ depletion and weak heart beat [12,77]. Obviously, this mechanism could be very important both for the physiological regulation of the channels during stress as well as for their pathophysiological malfunctioning. Therefore, it has attracted substantial research efforts from several laboratories. While in general phosphorylation of the S2808 site has been confirmed by various laboratories, specificity for PKA of this site, the conditions under which phosphorylation would occur and whether or not this leads to calstabin 2 dissociation have remained equivocal [57]. An additional PKA site has been identified at serine 2030 [58,78]. On the single channel level, functional changes after PKA-dependent phosphorylation have been described some time ago [79,80]. On the cellular level, the consequences of PKA-dependent RyR phosphorylation have been more difficult to pinpoint, partly because of the complex adjustments of multiple signaling networks downstream the activation of PKA in intact or permeabilized cells. Changes of Ca2+ spark parameters indeed were observed upon application of cAMP in permeabilized mouse cardiomyocytes, but were entirely attributable to the concomitant SERCA stimulation resulting from PLB phosphorylation, as they were not present in cells isolated from PLB ablated mice, where SERCA is already maximally stimulated [11]. Two-photon photolysis of caged Ca2+ to artificially trigger Ca2+ sparks suggested changes of RyR gating after β-adrenergic stimulation, since in resting Guinea pig myocytes larger Ca2+ release events were observed despite a decline of SR content [81]. However, when analyzing the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks at rest, this was later found to most likely depend on CaMKII activation [82].

Because of these difficulties to dissect the consequences of β-adrenergic stimulation on RyR function, transgenic animals have been engineered specifically targeting the serine 2808 site. Several animal models have been created where this serine is replaced by alanine, resulting in S2808A channels which can no longer be phosphorylated at this site [59,83]. Another model are the S2808D mice, which have a modification which corresponds to constitutively phosphorylated RyRs. Unfortunately, the generation of these animals has not fulfilled the expectation to clarify the open issues, as the results published in several reports have again been controversial. Initial studies with the S2808A mice showed that the modification was very subtle, did not disturb normal cardiac function and the animals had no overt phenotype. However, after myocardial infarction (MI) these mice were protected from developing heart failure and from arrhythmias induced by phosphodiesterase inhibition [59]. Reconstituted S2808A channels did not show elevated open probability after MI, in contrast to those from WT mice (an observation which is puzzling by itself, because the CaMKII phosphorylation site on these RyRs should still be functional [72]). This difference on the molecular level was proposed to be the underlying mechanism preventing SR Ca2+ leak, weak heartbeat and the susceptibility to arrhythmias in S2808A mice.

In a different laboratory, a further S2808A mouse was engineered and these animals were subjected to a pressure overload heart failure model after TAC [83]. In this study, no obvious cardioprotection was conferred to the animals by ablating the 2808 phosphorylation site. Furthermore, no substantial differences between WT and S2808A RyRs were present in the open probability and gating kinetics of reconstituted channels. This study then examined Ca2+ signaling and EC-coupling on the cellular level, including an analysis of Ca2+ sparks and waves. Again, no significant differences were found between the two groups of animals. These observations led the authors to conclude that the serine 2808 site only has a limited role in the pathogenesis of heart failure.

At present it remains unsettled why these apparently similar studies led to essentially opposite conclusions. One has to consider that the used disease models and the particular pathomechanisms activated in each of them (e.g. pressure overload after TAC versus ischemia / inflammatory disease without pressure overload but potentially more oxidative stress [84]) could result in quite different outcomes, as has been observed in another study investigating CaMKII dependent RyR phosphorylation [85], or that the RyRs of the two engineered animals do not operate in a perfectly identical way [86]. Alternatively, some of the resulting functional modifications may be rather subtle, and can be compensated by auto-regulatory features of the cardiac EC-coupling machinery [87] and are therefore difficult to detect.

Starting from the latter possibility, a detailed study was carried out to examine SR Ca2+ release kinetics, their spatial synchronization, and the improvement of this parameter by β-adrenergic stimulation when the communication between L-type Ca2+ channels and RyRs was challenged [88]. The reasoning for this approach was the notion that these events occur at the very interface between the L-type Ca2+ channels and the RyRs and might therefore reveal even subtle changes. When this communication was tested by using very small Ca2+ currents as triggers, substantial spatial desynchronization was observed. This was resynchronized upon β-adrenergic stimulation in the WT [89] but not in the S2808A cells. Furthermore, unlike WT cells, Ca2+ wave propagation was not accelerated upon β-adrenergic stimulation in S2808A cells. Together with the long delays observed in the release synchronization, this suggested the possibility of an intra-SR mechanism [46,56], whereby SR Ca2+ loading via SERCA would lead to sensitization of the RyR from the luminal side, thereby pushing the channel over the trigger threshold. The possibility of an intra-SR mechanism was then confirmed in reconstituted single RyR channels. At high SR Ca2+ concentrations, and only under this condition, WT channels indeed responded with a significantly larger increase in open probability upon PKA dependent phosporylation than S2808A channels. Regarding the ongoing controversy, the main conclusion from these studies is that the effects of serine 2808 phosphorylation are present but delicate and may be difficult to detect when SR Ca2+ content is not controlled experimentally (e.g. in vivo, when the auto-regulatory adjustments of SR Ca2+ content mentioned above may compensate for small changes of RyR open probability).

Taken together it appears that the mechanisms and consequences of PKA dependent RyR phosphorylation are less clear and potentially more subtle than those mediated by CaMKII. Whether and how these delicate changes translate into the in vivo situation is difficult to extrapolate and will require more research. In support for this expectation, a recent cross-breeding experiment between dystrophic mdx and S2808A mice indicated that the RyR mutation confers significant protection for cardiac disease manifestations and progression of the dystrophic cardiomyopathy in these animals (see below) [90].

4. Redox modification of RyR

4.1. RyR oxidation by ROS

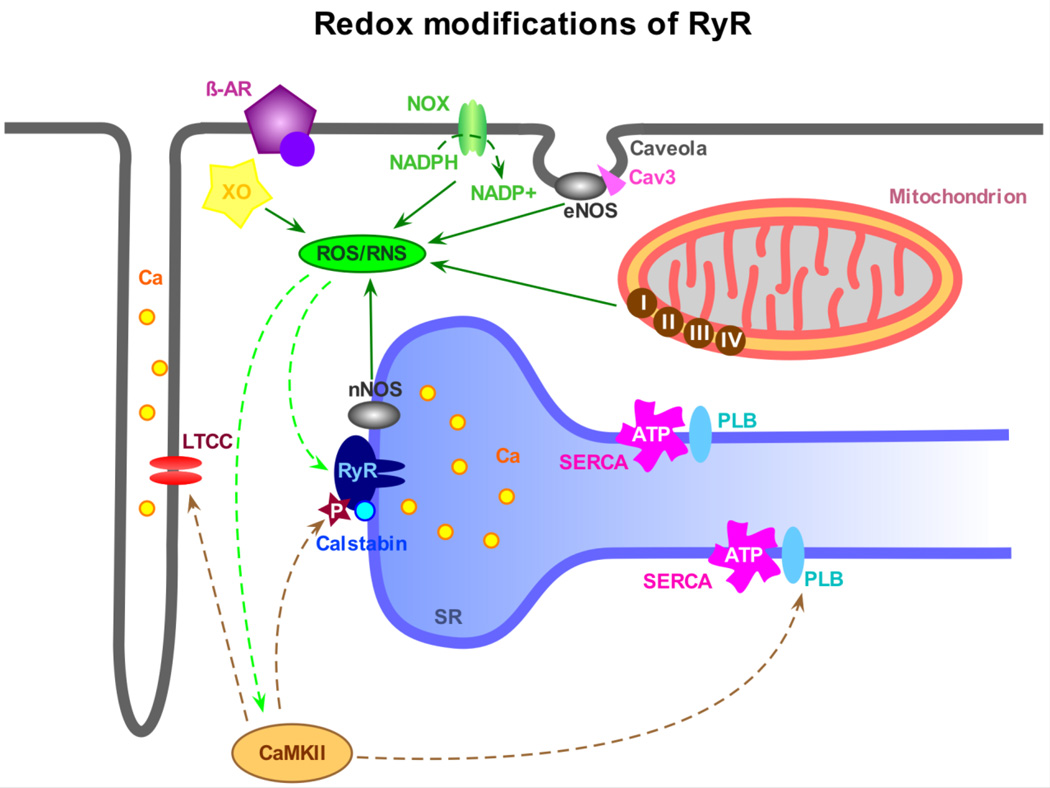

Changes of the cellular redox state give rise to another category of posttranslational RyR modifications, which do not only have a modulatory function but also play an important role in the development of various cardiac diseases. The term “intracellular redox potential” broadly describes the balance between reduced and oxidized proteins within cells, which in turn is determined by the level of generation and buffering of cellular reactive oxygen and reactive nitrogen species (ROS/RNS). There are multiple sources of ROS/RNS within the cell (see figure 2). They include but are not limited to NADPH oxidase (NOX), xanthine oxidase (XO), mitochondria and nitric oxide synthase (NOS). On the other end there are various cellular antioxidant defense components such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, thio- and glutaredoxins, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione, vitamins A, C and E, etc. Under physiological conditions, the extent of ROS/RNS accumulation is finely controlled by these scavenging and reducing mechanisms, and at low concentrations ROS/RNS serve as important intracellular messengers. An imbalance between generation of ROS/RNS and the efficiency of cellular defense systems can lead to a transient or persistent oxidative/nitrosative stress resulting in redox modifications of various cellular proteins, including those involved in Ca2+ homeostasis. The RyR is an important example, since it is known to be very susceptible to redox modifications. Each cardiac RyR tetramer contains a total of 364 cysteines [91]. In the presence of a physiological concentration of one of the major cellular “redox buffers” glutathione (5 mM) about 84 of these cysteines are free. The sulfhydryl groups of these cysteines are subject to reversible cross-linking, S-nitrosation (often referred to as S-nitrosylation) and S-glutathionylation. Numerous studies of RyRs incorporated in lipid bilayers convincingly showed that reversible redox modifications significantly affect the activity of RyR channels. Oxidative conditions generally increase the RyR open probability, while reducing agents do the opposite (e.g. [91–94]). Therefore, the functional consequence of a moderate cellular oxidative/nitrosative stress could be immediate enhancement of Ca2+ release from the SR in response to a given physiological trigger. This possibility has been supported by experiments with isolated SR vesicles (e.g. [91,95]). The increased Ca2+ sensitivity of RyRs and subsequently larger Ca2+ transients could have a positive inotropic effect on the cardiac function [96]. However, severe oxidative stress can cause irreversible and sustained activation of RyRs [91], increased Ca2+ leak from the SR, decreased SR Ca2+ load and finally a decline of beat-to-beat cellular Ca2+ transients with contractile dysfunction. Such conditions are usually associated with or even caused by the development of various cardiac abnormalities. Therefore, the role of RyR redox modifications in cardiac pathophysiology is currently under intensive investigation in multiple laboratories around the world.

Fig. 2.

Redox-modifications of RyRs. Changes in the redox potential of the myocyte have been shown to have a serious influence on protein function, especially at the level of the RyR. The main sources for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cardiomyocytes are the sarcolemmal NADPH oxidase (NOX), the xanthine oxidase (XO) and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (complex I through IV). ROS can glutathionylate free cysteine residues on the RyR and also act in an indirect way via CaMKII activation and subsequent RyR phosphorylation. Nitric oxide synthases (NOS) are mainly responsible for the production of nitric oxide (NO) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). In cardiomyocytes, sarcolemmal endothelial NOS (eNOS), which co-localizes with caveolin-3 (Cav3) in caveolae, and RyR-associated neuronal nNOS are primarily responsible for the production of NO, causing S-nitrosation at free thiol groups of the RyR and many other proteins. Most likely, these mechanisms work synergistically and induce parallel modifications of RyR function.

When the experimental gear was shifted from molecules and vesicles towards studies of cells, organs and organisms, it became obvious that the findings obtained from isolated RyR channels cannot be translated to more complex biological systems without a critical reevaluation. Besides the presence of various cellular sources for ROS, redox modification targets multiple intracellular sites including major proteins involved in EC coupling and all of them need to be considered in order to identify the link between each modification and the resulting changes of RyR function [97]. To discriminate between correlative, adaptive and causal posttranslational RyR modifications is often a daunting task.

Cardiac muscle has a substantial NOX activity (for reviews see [98,99]). It has been reported that NOX2 is the predominant isoform expressed in T-tubular and SR membranes of mature cardiomyocytes. Therefore, it is strategically positioned to modulate the activity of the RyRs. NOX is an enzyme that utilizes NADPH to produce superoxide anion. NOX2 was found to be overexpressed and/or its activity increased in dystrophic hearts [100,101], in hearts of patients with a history of atrial fibrillation [102], and in hearts subjected to tachycardic preconditioning [103]. Although the exact mechanisms of NOX activation under these pathological conditions remain unclear, it was shown that ROS produced by NOX stimulates SR Ca2+ release via at least two pathways: 1) direct oxidation or S-glutathionylation of RyRs or 2) indirectly through CaMKII activation [104] followed by phosphorylation of the RyRs. Reducing or ROS scavenging compounds could generally mitigate or prevent the consequences of oxidative stress in these experimental models. Another widely recognized source of ROS production in cardiac myocytes are mitochondria [105,106]. Mitochondria always generate a small amount of ROS through leakage in the electron transport chain during respiration. Under some pathophysiological conditions, such as ischemia/reperfusion, ROS produced by mitochondria become the main contributors to cellular oxidative stress. In this situation mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and subsequently ROS overproduction may trigger mitochondrial permeability transition, which in turn boosts ROS production via ROS-induced ROS release mechanisms [107,108]. There are also several reports indicating upregulation of XO activity in experimental models of heart failure [109]. Furthermore, contractile function and myocardial efficiency in HF could be improved by the treatment the animals with the xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol [110,111]. Overall, regardless of the source of their generation, ROS and subsequent oxidative modifications of RyRs have been directly held accountable for augmented stretch-induced Ca2+ responses and hypersensitive EC-coupling in dystrophic cardiomyocytes [101,112–115] as well as in impaired Ca2+ signaling in failing [116,117] and diabetic hearts [118,119].

4.2. RyR modifications by RNS

The two major isoforms of NO synthase (NOS) in cardiac myocytes are eNOS and nNOS. They have a specific sub-cellular localization and are possibly aimed at different targets in their microdomains, due to the short range of NO diffusion. The eNOS isoform is localized in the plasma membrane in caveolae through interaction with caveolin-3. In healthy cardiac muscle nNOS is mainly located in the SR membrane, linked to the RyRs. In failing or diseased hearts nNOS may partly redistribute to the sarcolemma. Normally, the iNOS isoform is not present in significant amounts, but this may be different during the development of cardiac diseases. NO produced by these enzymes can bind to free thiol groups on various proteins, including RyR, causing S-nitrosation and conformational changes. Alternatively, NO can act via the cGMP dependent pathway and activated PKG, a protein kinase which is thought to phosphorlyate the RyR at the S2814 CaMKII site, at least in vitro [60]. However, whether this occurs in vivo is presently unclear.

An important role for direct RyR nitrosation in cardiac EC-coupling and Ca2+ signaling was suspected already some time ago (for review see [96]), when it was found that the stretch-induced enhancement of cardiac Ca2+ signals and elevation of Ca2+ spark frequency was blunted in the presence of L-NAME, an unspecific inhibitor of all NOS isoforms [120]. The effect of stretch could be mimicked by adding the NO donor SNAP, which nearly doubled the Ca2+ spark frequency. Additional studies reported that NO could have diverse actions, depending on the preexisting extent of β-adrenergic stimulation. NO donors increased the Ca2+ spark frequency in a cGMP independent way at low (10 nM) concentrations of ISO, presumably by RyR nitrosation (but other mechanisms were not excluded) [121]. At 1 µM ISO a decrease of the spark frequency was observed, however this was accompanied (or caused) by a reduction of the SR Ca2+ content. In nNOS−/− mice, but not in eNOS−/− mice, hyponitrosation of the RyRs was observed, indicating that the structural proximity between nNOS and RyR may be functionally relevant. Interestingly, these RyRs exhibited more extensive oxidative modifications, thought to lead to elevated SR Ca2+ leak [122]. Thus, constitutive RyR S-nitrosation in WT animals may confer some protection of the channels against more severe oxidative modifications. This may be important in various diseases, where changes of the nitrosation have been implied in their pathology, but also in conferring some cardioprotection [123]. However, in another study with myocytes from nNOS−/− mice, Ca2+ spark frequencies and the SR Ca2+ leak at a given Ca2+ load were found to be reduced, and both could be normalized (i.e. increased) by exposure to an NO donor [124]. In line with these findings, RyRs were hypernitrosated in cardiomyocytes with upregulated nNOS activity and this was paralleled by increased SR Ca2+ leak and elevated fractional Ca2+ release [125]. Taken together, and considering the caveats when interpreting experimental data obtained from transgenic animals, these findings indicate that, depending on the conditions (e.g. on the extent of oxidative stress), nNOS signaling can also increase RyR activity in cardiac muscle, either directly or indirectly.

In one disease related study the extent of RyR nitrosation was quantified in mice with dystrophic cardiomyopathy and found to be increased around 4–5 fold [126], while PKA dependent RyR phosphorylation was not significantly elevated. This was accompanied by a doubling of the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and a propensity for arrhythmias. The extent of RyR oxidation and CaMKII-dependent RyR phosphorylation was not assessed directly, but the protective effect of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) suggests an important role of oxidative stress in dystrophic cardiomyopathy, as reported earlier ([100,101].

The general concept which emerges from these partly controversial studies, although rather diffuse, suggests that the reciprocal interactions between RyR modifications resulting from ROS and RNS and their functional outcome are very complex and not yet fully understood. While some observations suggest quite synergistic actions, in other experimental settings more competitive effects between ROS and RNS modifications become apparent. Interactions between ROS and RNS are possible in various ways, for example through their tightly connected chemistries (e.g. superoxide and NO can combine to form peroxynitrite [127]) or by competing for the same thiols on the RyR. A further complication in the interpretation of the experimental data may arise from the finding that RyR2 is nitrosated via S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and not by NO directly [94]. Further, most experiments were carried out at ambient oxygen pressure (~150 mmHg), but in the tissue there is much less oxygen (~10 mmHg). The degree of oxidation and the function of the cardiac RyR is modified by ambient O2 [94]. In any case, it seems that the precise balance between ROS and RNS is important, and that a NO/ROS disequilibrium can lead to abnormal RyR channel behavior [128].

5. Cross-talk between redox modifications and phosphorylation in disease

Recently, a number of studies have been carried out in a variety of cardiac disease models, focusing on modifications of RyR function and the conceivably underlying posttranslational modifications. A common finding in many of these studies was a sequential (i.e. during disease development) or simultaneous presence of several posttranslational RyR modifications. While such a pattern could result from parallel but unrelated changes of the involved pathways, it seems more plausible that these modifications are not independent from each other. There are numerous possibilities for significant cross-talk and synergisms among these signaling pathways such as ROS/RNS, phosphorylation and Ca2+ signals, from the origin (receptor or source of the signal) down to the target, the RyR itself (for reviews see [129,130]). In one scenario, boosting the Ca2+ transient by phosphorylating various Ca2+ signaling proteins may elevate mitochondrial Ca2+ content, followed by an increased mitochondrial metabolism and ROS production [105]. Mitochondrial ROS can further augment the Ca2+ signals by oxidizing multiple Ca2+ signaling proteins, as described above, but also by activating CaMKII via redox modification. This occurs in addition to the stimulation by the larger Ca2+ transients themselves and will lead to extra protein phosphorylation [104], thereby establishing multiple and coupled positive feed-back loops, which further amplify these signals [131]. Moreover, receptors and enzymes involved in the generation, modulation and termination (e.g. phosphatases, phosphodiesterases, ROS scavengers, SNO reductases) of these associated signals are often regulated via other functionally interconnected pathways. For example, β-adrenergic responsiveness is regulated by NO, creating a link between NO, phosphorylation and Ca2+ signals [132]. In turn, the activity of NOSes is Ca2+ sensitive [133]. The eNOS isoform (but not nNOS) is stimulated by ROS [134]. Most likely, many more direct and indirect possibilities for cross-talk between these pathways exist within cells.

Interactions between RyR oxidation and phosphorylation have been studied in dystrophic cardiomyopathy, a disease that combines a high degree of oxidative stress and excessive Ca2+ signals after mechanical stress, resulting from the lack of the protein dystrophin [101]. In one example, a cross-breeding approach has been applied to test for rescue from this disease by eliminating not the main pathomechanism, but another step in the vicious cycle [90]. Dystrophic mdx mice were crossed with RyR-S2808A mice, which carry RyRs that cannot be phosphorylated at this site. Ablation of this phosphorylation site protected these animals, even though not the main pathomechanism was targeted, but rather one of the other steps in the positive feed-back loop. Unlike mdx mice, these animals did not develop cardiac hypertrophy with fibrosis and showed improved cardiac function. Further, they were protected from isoproterenol-induced arrhythmias and SR Ca2+ leak. These findings suggest that PKA dependent RyR phosphorylation contributes to the abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis in dystrophic cardiomyopathy. Interestingly, and in apparent contrast to these findings, another study was not able to detect significant PKA dependent RyR phosphorylation in mdx mice [126]. However, more recent studies suggest that the disease phenotype and the pattern of RyR posttranslational modifications change in the course of dystrophic cardiomyopathy, and other diseases as well. Unlike oxidative stress and CaMKII activation, RyR phosphorylation by PKA seems to become important only at later stages of the disease, and is associated with elevated SR Ca2+ leak and reduced Ca2+ content [115].

6. Possible clinical relevance

A multitude of cardiac diseases are accompanied by acute or chronic hyperadrenergic states and/or oxidative cellular stress which can initiate vicious cycles and pathomechanisms involving RyR posttranslational modifications similar to those described above. Since phosphorylation, as well as oxidation and elevated Ca2+ concentration will increase the RyR open probability, the CICR mechanism may become very sensitive and unstable. To what extent these multiple changes and the concomitant posttranslational RyR modifications exert additive effects and whether they progress rapidly or slowly during the development of a given disease is not yet established and remains to be investigated. However, a number of recent experimental studies on the cellular level are in line with this possibility. Examples for diseases where posttranslational RyR modifications have been reported are congestive heart failure [116], dystrophic cardiomyopathy [101], diabetes [119], ischemia/reperfusion [135] and atrial fibrillation [136]. However, the clinical relevance of the presented experimental findings in general and the impact of the identified pathomechanisms and suspected cross-talk pathways in particular can ultimately only be confirmed in clinical trials. In such future pilot studies multipronged therapeutic strategies would need to be compared with established treatments targeting only one mechanism. Nevertheless, some of the animal studies carried out with various disease models are already fairly developed and can provide a solid foundation on which to base future clinical trials, possibly with studies in human cardiomyocytes and in larger animals as intermediate steps. Based on the available data a few disease entities have been identified in which posttranslational RyR modifications seem to make a substantial contribution to disease progression. One category of examples is a variety of disease models leading to heart failure (e.g. myocardial infarction, transverse aortic constriction (TAC), artificial tachypacing, dystrophic cardiomyopathy). In these entities both, oxidative RyR modifications and CaMKII (and possibly PKA) dependent RyR phosphorylation have been found to be present concurrently, but in various proportions [85,115,116,126,137,138]. The concomitant destabilization of the RyRs may also favor or underlie the occurrence of various forms of arrhythmias, initiated by diastolic Ca2+ release leading to delayed afterdepolarizations and extrasystoles. Not unexpectedly, the arrhythmogenicity of phosphorylated RyRs also appears to be instrumental in some forms of atrial fibrillation [139–142].

Another layer of complexity is added to the intricate mutual interactions of all the posttranslational modifications discussed above in patients carrying a mutation of the RyR2 [143,144]. These mutated channels often exhibit destabilized gating behavior, possibly arising from altered interaction (i.e. zipping) of RyR channel domains [145,146]. Many of these patients are prone to stress-induced arrhythmias, manifesting themselves as catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardias (CPVTs), potentially leading to sudden cardiac death. Cell lines and transgenic animals have been engineered expressing RyRs harboring mutations that were identified in families with CPVT patients [147–150]. These animals replicate the human disease phenotype and serve as disease models to investigate pathomechanisms arising from RyR mutations and to develop therapeutic approaches. In these disease models, arrhythmias could be provoked by tachypacing and/or by β-adrenergic stimulation. In cellular experiments, these cardiomyocytes exhibited elevated Ca2+ spark frequencies, a propensity for diastolic Ca2+ waves with delayed afterdepolarizations and reduced wave thresholds. These are all signs for disturbed channel gating with a predisposition towards abnormal Ca2+ sensitivity (cytosolic or SR luminal) of mutated channels. In summary, the phenotypes resulting from RyR mutations share many features with the functional consequences of the posttranslational modifications discussed above. While it is well established that physical or emotional stress can prompt CPVTs in patients harboring cardiac RyR mutations, it is so far unknown how stress exactly triggers these arrhythmias. Are they provoked by additional RyR sensitization originating from PKA or CaMKII dependent RyR phosphorylation? Or are they the result of the concomitant stimulation of the SERCA after PLB phosphorylation, leading to elevated SR Ca2+ loading? Or is it the combination of these two possibilities which is particularly detrimental?

7. Conclusion and outlook

While we start to understand the consequences of various posttranslational RyR modifications on the molecular level, we also develop the awareness for the extraordinary complexity of this issue on the cellular and organ level. This partly results from the multiple crosstalks and interactions of the various signaling pathways and their intertwined positive and negative feed-back loops. A large amount of research will thus be required to address the question whether all the regulatory and / or pathophysiologically important mechanisms changing RyR function behave in additive, competitive or mutually exclusive ways. To answer these and many similar questions relevant for other cardiac conditions, it needs to be understood in more detail, on the molecular level, how these modifications interact to bring about functional change. These findings then need to be integrated into the more complex situation of intact cells, organs and organisms, to determine their physiological and clinical relevance. Based on the presently available literature, only partly discussed above, one is inclined to predict that such interactions exist and are very important. Understanding these interactions will lay the foundation for the development of mechanism based therapies, potentially targeting several synergistically acting mechanisms simultaneously.

Highlights.

-

-

Cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR) function is affected by posttranslational modifications

-

-

These modifications of the RyRs contribute to cardiac regulation and disease

-

-

RyR phosphorylation and oxidative/nitrosative modifications are relevant modifications

-

-

Various pathways of signaling crosstalk, antagonism and synergies are involved

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by SNSF (31-132689 and 31-109693 to E.N.), NIH (HL093342 and AR053933 to N.Sh.) Swiss Foundation for Research on Muscle Diseases (to E.N and N.Sh.). Nina D. Ullrich was supported by Ambizione SNSF (PZ00P3_131987/1). Eva Polakova was recipient of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from AHA.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- cADPR

Cyclic ADP ribose

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CICR

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release

- CPVT

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- EC

Excitation-Contraction

- mdx

Mouse model of muscular dystrophy

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RNS

Reactive nitrogen species

- NOX

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase

- NOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- PKA

Protein kinase A

- PLB

Phospholamban

- RyR

Ryanodine receptor

- SERCA

Sarco-(endo) plasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump

- SR

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

- XO

Xanthine oxidase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikemoto N, Ronjat M, Mészáros LG, Koshita M. Postulated role of calsequestrin in the regulation of calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6764–6771. doi: 10.1021/bi00442a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shannon TR, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Potentiation of fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by total and free intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration. Biophys. J. 2000;78:334–343. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lokuta AJ, Meyers MB, Sander PR, Fishman GI, Valdivia HH. Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptors by sorcin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25333–25338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mejia-Alvarez R, Kettlun C, Rios E, Stern M, Fill M. Unitary Ca2+ current through cardiac ryanodine receptor channels under quasi-physiological ionic conditions. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:177–186. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hidalgo C, Bull R, Marengo JJ, Perez CF, Donoso P. SH oxidation stimulates calcium release channels (ryanodine receptors) from excitable cells. Biol. Res. 2000;33:113–124. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602000000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stange M, Xu L, Balshaw D, Yamaguchi N, Meissner G. Characterization of recombinant skeletal muscle (Ser-2843) and cardiac muscle (Ser-2809) ryanodine receptor phosphorylation mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51693–51702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyorke I, Hester N, Jones LR, Györke S. The role of calsequestrin, triadin, and junctin in conferring cardiac ryanodine receptor responsiveness to luminal calcium. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2121–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74271-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laver DR. Ca2+ stores regulate ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels via luminal and cytosolic Ca2+ sites. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3541–3555. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabiato A. Simulated calcium current can both cause calcium loading in and trigger calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned canine cardiac Purkinje cell. J. Gen. Physiol. 1985;85:291–320. doi: 10.1085/jgp.85.2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Kranias EG, Mignery GA, Bers DM. Protein kinase A phosphorylation of the ryanodine receptor does not affect calcium sparks in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 2002;90:309–316. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.105660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huke S, Bers DM. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation at Serine 2030, 2808 and 2814 in rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2008;376:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scriven DR, Dan P, Moore ED. Distribution of proteins implicated in excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2000;79:2682–2691. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76506-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi T, Martone ME, Yu Z, Thor A, Doi M, Holst MJ, Ellisman MH, Hoshijima M. Three-dimensional electron microscopy reveals new details of membrane systems for Ca2+ signaling in the heart. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:1005–1013. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng X, Xiao B, Cai S, Huang X, Li F, Bolstad J, Trujillo R, Airey J, Chen SRW, Wagenkencht T, Liu Z. Three-dimensional localization of serine 2808, a phosphorylation site in cardiac ryanodine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:25929–25939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704474200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serysheva II, Hamilton SL, Chiu W, Ludtke SJ. Structure of Ca2+ release channel at 14 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirokova N, Niggli E. Studies of RyR function in situ. Methods. 2008;46:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minta A, Kao JP, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic calcium based on rhodamine and fluorescein chromophores. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:8171–8178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paredes RM, Etzler JC, Watts LT, Zheng W, Lechleiter JD. Chemical calcium indicators. Methods. 2008;46:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephens DJ, Allan VJ. Light microscopy techniques for live cell imaging. Science. 2003;300:82–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1082160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danila CI, Hamilton SL. Phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors. Biol. Res. 2004;37:521–525. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehnart SE, Wehrens XHT, Kushnir A, Marks AR. Cardiac ryanodine receptor function and regulation in heart disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1015:144–159. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim S-O, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zalk R, Lehnart SE, Marks AR. Modulation of the ryanodine receptor and intracellular calcium. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:367–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.053105.094237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meissner G. Regulation of ryanodine receptor ion channels through posttranslational modifications. Curr. Top. Membr. 2010;66:91–113. doi: 10.1016/S1063-5823(10)66005-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donoso P, Sánchez G, Bull R, Hidalgo C. Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor activity by ROS and RNS. Front. Biosci. 2011;16:553–567. doi: 10.2741/3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santos CXC, Anilkumar N, Zhang M, Brewer AC, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac myocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;50:777–793. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao D, Oka S-I, Brady CD, Haendeler J, Eaton P, Sadoshima J. Redox modification of cell signaling in the cardiovascular system. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012;52:550–558. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bers DM. Macromolecular complexes regulating cardiac ryanodine receptor function. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2004;37:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marks AR, Marx SO, Reiken S. Regulation of ryanodine receptors via macromolecular complexes: a novel role for leucine/isoleucine zippers. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:166–170. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehnart SE, Wehrens XHT, Reiken S, Warrier S, Belevych AE, Harvey RD, Richter W, Jin SLC, Conti M, Marks AR. Phosphodiesterase 4D deficiency in the ryanodine-receptor complex promotes heart failure and arrhythmias. Cell. 2005;123:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Currie S, Loughrey CM, Craig M-A, Smith GL. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIdelta associates with the ryanodine receptor complex and regulates channel function in rabbit heart. Biochem. J. 2004;377:357–366. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca2+ release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys. J. 1999;77:1528–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niggli E, Shirokova N. A guide to sparkology: The taxonomy of elementary cellular Ca2+ signaling events. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipp P, Niggli E. Submicroscopic calcium signals as fundamental events of excitation--contraction coupling in guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1996;492:31–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brochet DXP, Xie W, Yang D, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Quarky calcium release in the heart. Circ. Res. 2011;108:210–218. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipp P, Niggli E. Fundamental calcium release events revealed by two-photon excitation photolysis of caged calcium in Guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1998;508(Pt 3):801–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.801bp.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobie EA, Guatimosim S, Gómez-Viquez L, Song L-S, Hartmann H, Saleet Jafri M, Lederer WJ. The Ca2+ leak paradox and rogue ryanodine receptors: SR Ca2+ efflux theory and practice. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2006;90:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bovo E, Mazurek SR, Blatter LA, Zima AV. Regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak by cytosolic Ca2+ in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2011;589:6039–6050. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.214171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng H, Lederer MR, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks and [Ca2+]i waves in cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:C148–C159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.1.C148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keizer J, Smith GD. Spark-to-wave transition: saltatory transmission of calcium waves in cardiac myocytes. Biophysical Chemistry. 1998;72:87–100. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(98)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izu LT, Wier WG, Balke CW. Evolution of cardiac calcium waves from stochastic calcium sparks. Biophys. J. 2001;80:103–120. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75998-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller M, Kao JPY, Egger M, Niggli E. Calcium waves driven by “sensitization” wave-fronts. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;74:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laver DR, Baynes TM, Dulhunty AF. Magnesium inhibition of ryanodine-receptor calcium channels: evidence for two independent mechanisms. J. Membr. Biol. 1997;156:213–229. doi: 10.1007/s002329900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soeller C, Cannell MB. Numerical simulation of local calcium movements during L-type calcium channel gating in the cardiac diad. Biophys. J. 1997;73:97–111. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Gyorke I, Volpe P, Williams SC, Györke S. Calsequestrin determines the functional size and stability of cardiac intracellular calcium stores: Mechanism for hereditary arrhythmia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:11759–11764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932318100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chopra N, Yang T, Asghari P, Moore ED, Huke S, Akin B, Cattolica RA, Perez CF, Hlaing T, Knollmann-Ritschel BEC, Jones LR, Pessah IN, Allen PD, Franzini-Armstrong C, Knollmann BC. Ablation of triadin causes loss of cardiac Ca2+ release units, impaired excitation-contraction coupling, and cardiac arrhythmias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:7636–7641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902919106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato D, Bers DM. How does stochastic ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca leak fail to initiate a Ca spark? Biophys. J. 2011;101:2370–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fabiato A. Time and calcium dependence of activation and inactivation of calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned canine cardiac Purkinje cell. J. Gen. Physiol. 1985;85:247–289. doi: 10.1085/jgp.85.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevens SCW, Terentyev D, Kalyanasundaram A, Periasamy M, Györke S. Intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ oscillations are driven by dynamic regulation of ryanodine receptor function by luminal Ca2+ in cardiomyocytes. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2009;587:4863–4872. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stern MD. Theory of excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 1992;63:497–517. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81615-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marx SO, Gaburjakova J, Gaburjakova M, Henrikson C, Ondrias K, Marks AR. Coupled gating between cardiac calcium release channels (ryanodine receptors) Circ. Res. 2001;88:1151–1158. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao B, Tian X, Xie W, Jones PP, Cai S, Wang X, Jiang D, Kong H, Zhang L, Chen K, Walsh MP, Cheng H, Chen SRW. Functional consequence of protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor: sensitization of store overload-induced Ca2+ release. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30256–30264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez P. Stoichiometric phosphorylation of cardiac ryanodine receptor on serine 2809 by calmodulin-dependent kinase II and protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:38593–38600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C301180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiao B, Jiang MT, Zhao M, Yang D, Sutherland C, Lai FA, Walsh MP, Warltier DC, Cheng H, Chen SRW. Characterization of a novel PKA phosphorylation site, serine-2030, reveals no PKA hyperphosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor in canine heart failure. Circ. Res. 2005;96:847–855. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163276.26083.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wehrens XHT, Lehnart SE, Reiken S, Vest JA, Wronska A, Marks AR. Ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel PKA phosphorylation: a critical mediator of heart failure progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:511–518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510113103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takasago T, Imagawa T, Furukawa K, Ogurusu T, Shigekawa M. Regulation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor by protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation. J. Biochem. 1991;109:163–170. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bers DM. Ryanodine receptor S2808 phosphorylation in heart failure: smoking gun or red herring. Circ. Res. 2012;110:796–799. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valdivia HH. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and heart failure: phasing out S2808 and “criminalizing” S2814. Circ. Res. 2012;110:1398–1402. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wehrens XHT. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ. Res. 2004;94:e61–e70. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125626.33738.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lokuta AJ, Rogers TB, Lederer WJ, Valdivia HH. Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptors of swine and rabbit by a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation mechanism. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1995;487:609–622. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang D, Zhu W-ZZ, Xiao B, Brochet DXP, Chen SRW, Lakatta EG, Xiao R-P, Cheng H. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II-dependent phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors suppresses Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2007;100:399–407. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258022.13090.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo T, Zhang T, Mestril R, Bers DM. Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation of ryanodine receptor does affect calcium sparks in mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 2006;99:398–406. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000236756.06252.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maier LS. Transgenic CaMKIIδC overexpression uniquely alters cardiac myocyte Ca2+ handling: reduced SR Ca2+ load and activated SR Ca2+ release. Circ. Res. 2003;92:904–911. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069685.20258.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dybkova N, Sedej S, Napolitano C, Neef S, Rokita AG, Hünlich M, Brown JH, Kockskämper J, Priori SG, Pieske B, Maier LS. Overexpression of CaMKIIδc in RyR2R4496C+/− knock-in mice leads to altered intracellular Ca2+ handling and Increased mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;57:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Backs J, Backs T, Neef S, Kreusser MM, Lehmann LH, Patrick DM, Grueter CE, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill JA, Katus HA, Bassel-Duby R, Maier LS, Olson EN. The δ isoform of CaM kinase II is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling after pressure overload. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:2342–2347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813013106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ling H, Zhang T, Pereira L, Means CK, Cheng H, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Peterson KL, Chen J, Bers D, Heller Brown J. Requirement for Ca2+/calmodulin–dependent kinase II in the transition from pressure overload–induced cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:1230–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI38022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kushnir A, Shan J, Betzenhauser MJ, Reiken S, Marks AR. Role of CaMKIIδ phosphorylation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor in the force frequency relationship and heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:10274–10279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005843107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Oort RJ, McCauley MD, Dixit SS, Pereira L, Yang Y, Respress JL, Wang Q, de Almeida AC, Skapura DG, Anderson ME, Bers DM, Wehrens XHT. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II promotes life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in mice with heart failure. Circulation. 2010;122:2669–2679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huke S, DeSantiago J, Kaetzel MA, Mishra S, Brown JH, Dedman JR, Bers DM. SR-targeted CaMKII inhibition improves SR Ca2+ handling, but accelerates cardiac remodeling in mice overexpressing CaMKIIδC. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;50:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang R, Khoo MSC, Wu Y, Yang Y, Grueter CE, Ni G, Price EE, Thiel W, Guatimosim S, Song L-S, Madu EC, Shah AN, Vishnivetskaya TA, Atkinson JB, Gurevich VV, Salama G, Lederer WJ, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:409–417. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sossalla S, Fluschnik N, Schotola H, Ort KR, Neef S, Schulte T, Wittkopper K, Renner A, Schmitto JD, Gummert J, El-Armouche A, Hasenfuss G, Maier LS. Inhibition of elevated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II improves contractility in human failing myocardium. Circ. Res. 2010;107:1150–1161. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.220418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheng J, Xu L, Lai D, Guilbert A, Lim HJ, Keskanokwong T, Wang Y. CaMKII inhibition in heart failure, beneficial, harmful, or both. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012;302:H1454–H1465. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00812.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Antos CL, Frey N, Marx SO, Reiken S, Gaburjakova M, Richardson JA, Marks AR, Olson EN. Dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden death resulting from constitutive activation of protein kinase A. Circ. Res. 2001;89:997–1004. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xiao B, Sutherland C, Walsh MP, Chen SRW. Protein kinase A phosphorylation at serine-2808 of the cardiac Ca2+-release channel (ryanodine receptor) does not dissociate 12.6-kDa FK506-binding protein (FKBP12.6) Circ. Res. 2004;94:487–495. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000115945.89741.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hain J, Nath S, Mayrleitner M, Fleischer S, Schindler H. Phosphorylation modulates the function of the calcium release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum from skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 1994;67:1823–1833. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80664-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Valdivia HH, Kaplan JH, Ellis-Davies GCR, Lederer WJ. Rapid adaptation of cardiac ryanodine receptors: modulation by Mg2+ and phosphorylation. Science. 1995;267:1997–2000. doi: 10.1126/science.7701323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lindegger N, Niggli E. Paradoxical SR Ca2+ release in guinea-pig cardiac myocytes after β-adrenergic stimulation revealed by two-photon photolysis of caged Ca2. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2005;565:801–813. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ogrodnik J, Niggli E. Increased Ca2+ leak and spatiotemporal coherence of Ca2+ release in cardiomyocytes during -adrenergic stimulation. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 2010;588:225–242. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Benkusky NA, Weber CS, Scherman JA, Farrell EF, Hacker TA, John MC, Powers PA, Valdivia HH. Intact beta-adrenergic response and unmodified progression toward heart failure in mice with genetic ablation of a major protein kinase A phosphorylation site in the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ. Res. 2007;101:819–829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Houser SR, Margulies KB, Murphy AM, Spinale FG, Francis GS, Prabhu SD, Rockman HA, Kass DA, Molkentin JD, Sussman MA, Koch WJ. Animal models of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ. Res. 2012;111:131–150. doi: 10.1161/RES.0b013e3182582523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Respress JL, van Oort RJ, Li N, Rolim N, Dixit SS, deAlmeida A, Voigt N, Lawrence WS, Skapura DG, Skardal K, Wisloff U, Wieland T, Ai X, Pogwizd SM, Dobrev D, Wehrens XHT. Role of RyR2 Phosphorylation at S2814 During Heart Failure Progression. Circ. Res. 2012;110:1474–1483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cook SA, Clerk A, Sugden PH. Are transgenic mice the “alkahest” to understanding myocardial hypertrophy and failure? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009;46:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Venetucci LA, Trafford AW, Eisner DA. Increasing ryanodine receptor open probability alone does not produce arrhythmogenic calcium waves: threshold sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content is required. Circ. Res. 2007;100:105–111. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252828.17939.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ullrich ND, Valdivia HH, Niggli E. PKA phosphorylation of cardiac ryanodine receptor modulates SR luminal Ca2+ sensitivity. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012;53:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Litwin SE, Zhang D, Bridge JH. Dyssynchronous Ca2+ sparks in myocytes from infarcted hearts. Circ. Res. 2000;87:1040–1047. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sarma S, Li N, van Oort RJ, Reynolds C, Skapura DG, Wehrens XHT. Genetic inhibition of PKA phosphorylation of RyR2 prevents dystrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:13165–13170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004509107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu L, Eu JP, Meissner G, Stamler JS. Activation of the cardiac calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) by poly-S-nitrosylation. Science. 1998;279:234–237. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marengo JJ, Hidalgo C, Bull R. Sulfhydryl oxidation modifies the calcium dependence of ryanodine-sensitive calcium channels of excitable cells. Biophys. J. 1998;74:1263–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77840-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Salama G, Menshikova EV, Abramson JJ. Molecular interaction between nitric oxide and ryanodine receptors of skeletal and cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Antiox. Redox Sig. 2000;2:5–16. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sun J, Yamaguchi N, Xu L, Eu JP, Stamler JS, Meissner G. Regulation of the cardiac muscle ryanodine receptor by O2 tension and S-nitrosoglutathione. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13985–13990. doi: 10.1021/bi8012627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Boraso A, Williams AJ. Modification of the gating of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel by H2O2 and dithiothreitol. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:H1010–H1016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lim G, Venetucci L, Eisner DA, Casadei B. Does nitric oxide modulate cardiac ryanodine receptor function?, Implications for excitation-contraction coupling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008;77:256–264. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuster GM, Lancel S, Zhang J, Communal C, Trucillo MP, Lim CC, Pfister O, Weinberg EO, Cohen RA, Liao R, Siwik DA, Colucci WS. Redox-mediated reciprocal regulation of SERCA and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger contributes to sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ depletion in cardiac myocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:1182–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bedard K, Krause K-H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Akki A, Zhang M, Murdoch C, Brewer A, Shah AM. NADPH oxidase signaling and cardiac myocyte function. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009;47:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Williams IA, Allen DG. The role of reactive oxygen species in the hearts of dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H1969–H1977. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00489.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jung C, Martins AS, Niggli E, Shirokova N. Dystrophic cardiomyopathy: amplification of cellular damage by Ca2+ signalling and reactive oxygen species-generating pathways. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;77:766–773. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim YM, Guzik TJ, Zhang YH, Zhang MH, Kattach H, Ratnatunga C, Pillai R, Channon KM, Casadei B. A myocardial Nox2 containing NAD(P)H oxidase contributes to oxidative stress in human atrial fibrillation. Circ. Res. 2005;97:629–636. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000183735.09871.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sánchez G, Pedrozo Z, Domenech RJ, Hidalgo C, Donoso P. Tachycardia increases NADPH oxidase activity and RyR2 S-glutathionylation in ventricular muscle. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;39:982–991. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Erickson JR, Joiner M-LA, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O'Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham A-JL, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu S-SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C817–C833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Davidson SM, Duchen MR. Calcium microdomains and oxidative stress. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:561–574. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1001–1014. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang W, Fang H, Groom L, Cheng A, Zhang W, Liu J, Wang X, Li K, Han P, Zheng M, Yin J, Wang W, Mattson MP, Kao JPY, Lakatta EG, Sheu S-SS, Ouyang K, Chen J, Dirksen RT, Cheng H. Superoxide flashes in single mitochondria. Cell. 2008;134:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gonzalez DR, Treuer AV, Castellanos J, Dulce RA, Hare JM. Impaired S-nitrosylation of the ryanodine receptor caused by xanthine oxidase activity contributes to calcium leak in heart failure. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:28938–28945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cappola TP, Kass DA, Nelson GS, Berger RD, Rosas GO, Kobeissi ZA, Marban E, Hare JM. Allopurinol improves myocardial efficiency in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;104:2407–2411. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.098928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ukai T, Cheng CP, Tachibana H, Igawa A, Zhang ZS, Cheng HJ, Little WC. Allopurinol enhances the contractile response to dobutamine and exercise in dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation. 2001;103:750–755. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.5.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]