Abstract

The tissue engineering strategy is a new approach for the regeneration of cementum, which is essential for the regeneration of the periodontal tissue. This strategy involves the cell cultures present in this tissue, called cementoblasts, and located on an appropriate substrate for posterior implantation in the regeneration site. Prior studies from our research group have shown that the proliferation and viability of cementoblasts increase in the presence of the ionic dissolution products of bioactive glass particles. Therefore, one possible approach to obtaining adequate substrates for cementoblast cultures is the development of composite membranes containing bioactive glass. In the present study, composite films of chitosan-polyvinyl alcohol-bioactive glass containing different glass contents were developed. Glutaraldehyde was also added to allow for the formation of cross-links and changes in the degradation rate. The glass phase was introduced in the material by a sol-gel route, leading to an organic-inorganic hybrid. The films were characterized by Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with electron dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. Bioactivity tests were also conducted by immersion of the films in simulated body fluid (SBF). Films containing up to 30% glass phase could be obtained. The formation of calcium phosphate was observed after the immersion of the films. A calcium phosphate layer formed more quickly on materials containing higher bioactive glass contents. In the hybrid containing 23% bioactive glass, a complete layer was formed after 24 h immersion, showing the high bioactivity of this material. However, despite the higher in vitro bioactivity, the film with 23% glass showed lower mechanical properties compared with films containing up to 17% glass.

Keywords: chitosan, Key words: bioactive glass, membranes, PVA, sol-gel

Introduction

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease affecting the tissues that support the teeth located in the maxilla and mandible. The ideal treatment for this disease would be the restoration of essential structures, such as cement, through tissue engineering.1 Cementum, which is quite similar to bone tissue, is a very thin mineralized connective tissue covering the entire surface of the tooth root. Cementum cells are called cementoblasts. Prior studies from our research group have shown that the proliferation and viability of cementoblasts have proven to be higher in the presence of ionic dissolution products of bioactive glass particles, demonstrating that this is an interesting material to be used as a tissue engineering strategy for the regeneration of the cementum.2 Tissue engineering is an area of research that involves the development of a matrix to support cells, bioactive molecules and cellular response, in turn promoting differentiation and regeneration. Therefore, one possible approach to obtaining suitable substrates for cementoblast cultures is the development of a thin and flexible membrane, containing bioactive glass particles to stimulate the proliferation of cementoblasts.

In previous studies,3-7 the chitosan-PVA system was studied within the entire composition range. Chitosan is taken from the alkaline deacetylation of chitin, an abundant natural polymer commonly found in the shells of crustaceans. This polymer is soluble in acid solutions of pH < 6.5 and has a high positive charge of the -NH3+ groups when dissolved. Its cationic nature is responsible for important properties, such as its aggregation with anionic compounds, its adhesion to surfaces with negative charges and its antibacterial activity. Other properties that justify the interest in this polymer’s application in medicine include its biocompatibility, its biodegradability into harmless products and its affinity for proteins.8,9 However, the strength and flexibility of chitosan are limited. Therefore, its mixture with other polymers is a procedure used to obtain or change the properties of interest. As such, PVA is added to improve mechanical properties. The PVA hydrogel has an excellent transparency, soft consistency as a membrane, excellent chemical resistance, biocompatibility and biodegradability.10-12 de Souza Costa-Júnior et al.4 noted that a decrease in both the strain and toughness of blends containing chitosan, as compared with films with only PVA, could be observed.

Bioactive glasses have been extensively studied in recent decades, as they contain interesting properties, especially when applied as an alternative method to repair parts of the mineralized tissues of the skeletal system.13-15 When implanted in the body, these glasses produce a specific biological response at the material interface, resulting in the formation of a link between the tissue and the material.16 Moreover, one important finding was that products of bioactive glass dissolution exert genetic control over the cell cycle of osteoblasts and rapid expression of genes that regulate osteogenesis and the production of growth factors.17 Concerning the similarity of some properties of osteoblasts in bone tissue and cementoblasts in cementum, the presence of the bioactive phase provides a great potential to positively influence the proliferation of cementoblasts, as already demonstrated by our preliminary studies.

In the present study, the bioactive glass was introduced into the material by the sol-gel route, resulting in an organic-inorganic hybrid. One of the advantages of the sol-gel route is the synthesis of ceramics from a mixture of alkoxide and/or salts, at low temperature, allowing for the incorporation of organic materials with a low risk of thermal degradation and molecular combination of phases. Other advantages of the process include: (1) easily obtained as films and (2) the tendency of glasses obtained through the sol-gel route to have greater bioactivity than those obtained by conventional melting, most likely due to more surface area, which, in turn, facilitates the actions of the ion exchange groups and exposes silanol groups, which are important for the nucleation of minerals.18,19 In this work, chitosan-polyvinyl alcohol-bioactive glass composite membranes were developed, resulting in films containing different amounts of glass. The blend containing 75% PVA-25% chitosan was chosen for the development of the composites. Glutaraldehyde was added to allow for cross-linking as well as changes in the degradation rate.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of obtained films

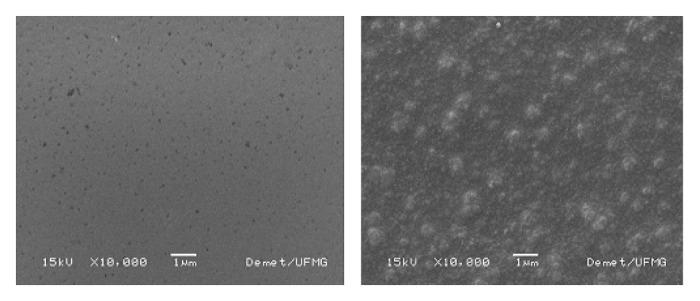

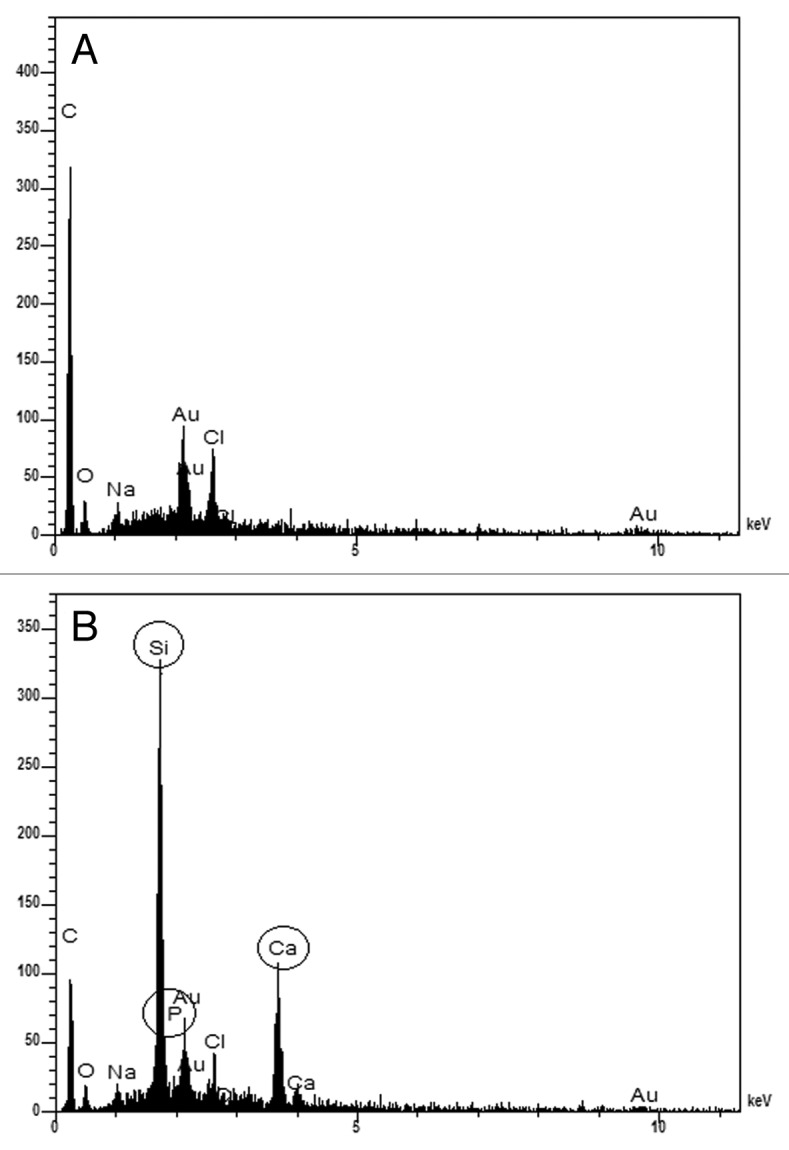

The images of films before immersion (Fig. 1) indicate that the film with 0% of glass has a relatively smoother surface than the film with 23% of glass. The rougher surface of the hybrid film could be an indication of possible phase separation. However, the EDS analysis of different points in both films show no major film composition variations, indicating certain homogeneity of the films. Nevertheless, the morphological rough aspect of the film with 23% glass may be due to differences in the polymer and inorganic phase distribution not detected by EDS analysis. The comparison by EDS analysis between the polymeric film (Fig. 2A) and the hybrid film (Fig. 2B) indicates the presence of Si, Ca and P, therefore confirming the inorganic phase incorporation into the hybrid films (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

SEM images of films with: (A) 0% and (B) 23% of bioactive glass before soaking into SBF (10,000x magnification).

Figure 2.

EDS spectra of films with: (A) 0% and (B) 23% of bioactive glass before immersion in SBF.

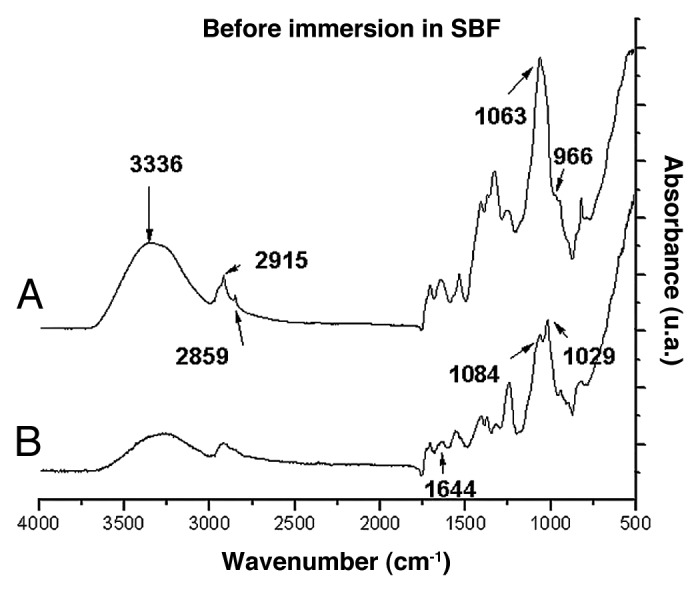

Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra for films with chitosan and PVA cross-linked with glutaraldehyde with 0% and 23% of glass before immersion in SBF. The characteristic peaks of chitosan and PVA and the peak at 1,644 cm-1, associated with the imine C=N bond (Schiff base) formed by the reaction of the amino group of chitosan and aldehyde groups from the cross-linker (glutaraldehyde), could be identified. It is also observed that as the glass percentage in the film increases, two peaks, 1,084 and 1,029 cm-1, associated with chemical groups in PVA and chitosan, respectively,4 undergo a broadening and overlapping of peaks due to the effect of Si-O-Si stretching-vibration (at 1,000–1,100 cm-1). The appearance of the band at 966 cm-1 was also noted, corresponding to the Si-OH stretching-vibration.19

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of films of chitosan/PVA/ glutaraldehyde with (A) 0% and (B) 23% of bioactive glass.

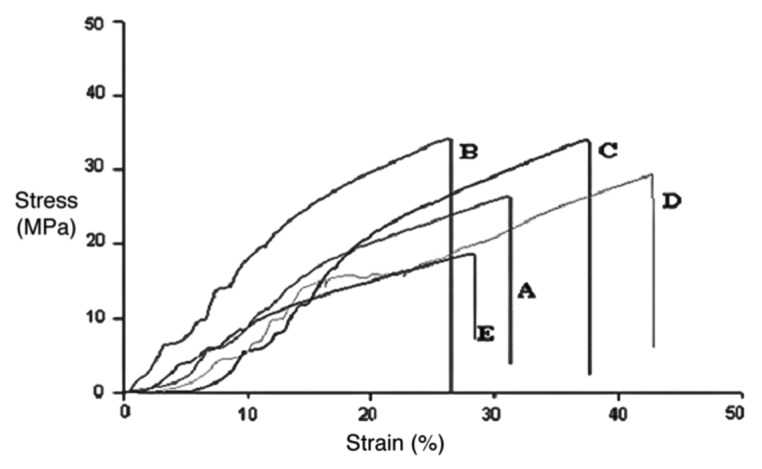

Figure 4 shows the stress-strain curves for films of chitosan and PVA cross-linked with glutaraldehyde with different percentages of bioactive glass. Average values with the standard deviations from these samples are presented in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Stress-Strain curves of films with: (A) 0%, (B) 5%, (C) 9%, (D) 17%, (E) 23% of bioactive glass.

Table 1. Values of ultimate tensile strength and maximum strain for films with 0 to 23 wt% of bioactive glass.

| Bioactive glass content in the film (wt%) | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Maximum Strain (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 |

25 ± 4 |

33 ± 7 |

| 5 |

34 ± 7 |

27 ± 3 |

| 9 |

34 ± 3 |

32 ± 4 |

| 17 |

30 ± 2 |

33 ± 5 |

| 23 | 20 ± 2 | 24 ± 4 |

Statistical analysis of the results show that there is no significant difference between maximum stress values for films with 0–17% glass, but there is difference between these compositions and the films with 23% glass. For the maximum strain, although differences were observed in the average values for different compositions, there were no statistically significant differences. Therefore, we can say that values of maximum stress proved to be lower for the film containing 23% of glass, as compared with those with 0–17% of glass, suggesting better mechanical properties for films with 0–17% glass.

Analysis of bioactivity

The hybrid synthesis conditions result in acid byproducts; however, the polymer content is sensitive to high temperatures, which restrains the elimination of toxic products by heat treatment. When in contact with the culture medium, hybrid dissolution products can modify the pH of the medium and cell growth, promoting lower cell viability. If this should occur, it will require a neutralization step to reduce the acidity of the samples and make them more biocompatible. Therefore, the pH of the SBF solution was measured at 37°C. It could be noted that, before the samples were immersed in SBF, the solution initially prepared at pH = 7.40 showed pH = 7.48. As such, no significant change in the pH of the SBF after different immersion times could be observed.

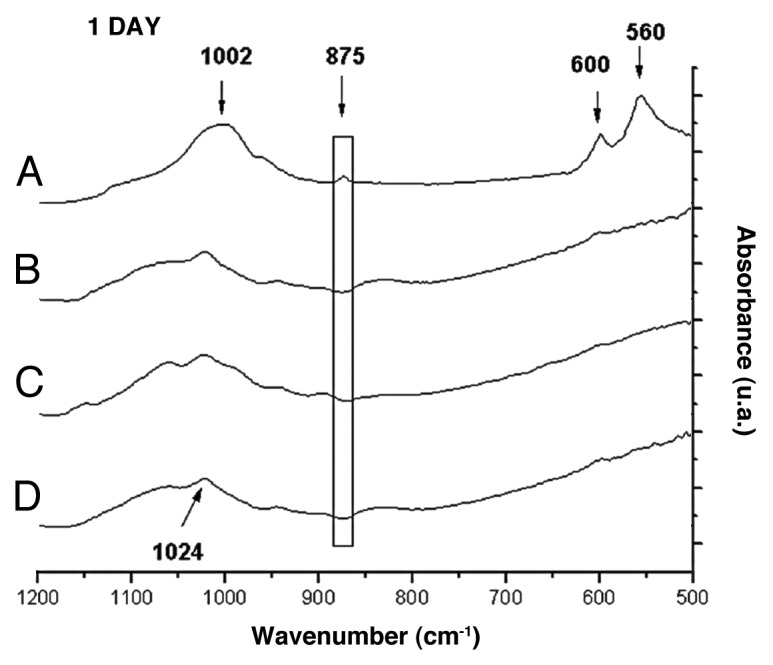

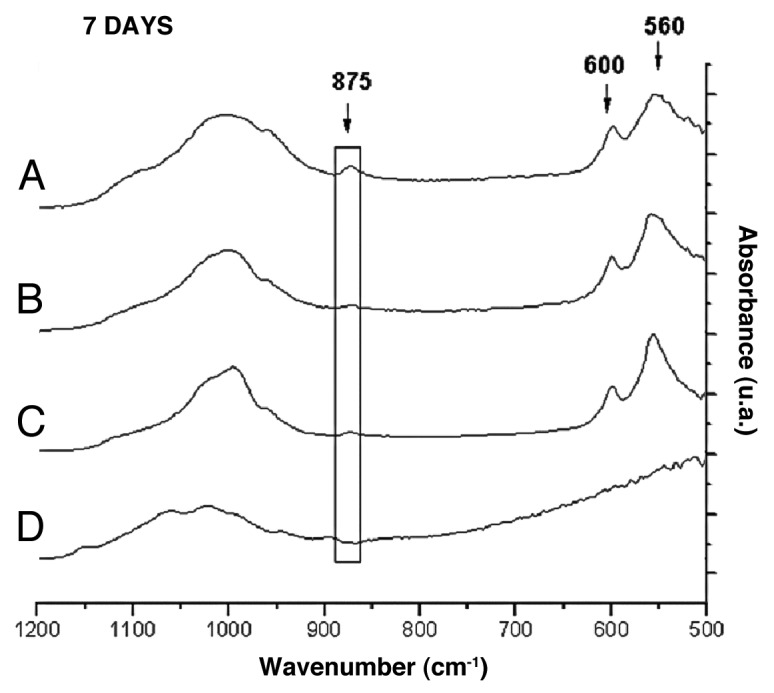

Figure 5 shows the FTIR spectra for films with 0–23% glass content after 1 d of immersion in SBF. A peak displacement could be observed between 1,024 cm-1 and 1,002 cm-1. This effect occurs in direct proportion to the increase in the glass percentage within the film, which corresponds to the appearance of the P-O stretching vibration. The peak at 875 cm-1 corresponds to the C-O bending-vibration of CO3-2 incorporated into the films and can be observed only in the film with 23% glass, along with peaks at 560 and 600 cm-1 associated with the P-O bending-vibration. These peaks were not identified after 3 d of immersion in films with 9% and 17% of glass contents. However, the spectra for films after 7 d of immersion (Fig. 6) indicate that films with 9 and 17% exhibit the same peaks at 1,002 cm-1, 875 cm-1, 560 and 600 cm-1.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of films with: (A) 23%, (B) 17%, (C) 9%, (D) 0% of bioactive glass after 1 d of immersion in SBF.

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of films with: (A) 23%; (B) 17%; (C) 9%; (D) 0% of bioactive glass after 7 d of immersion in SBF.

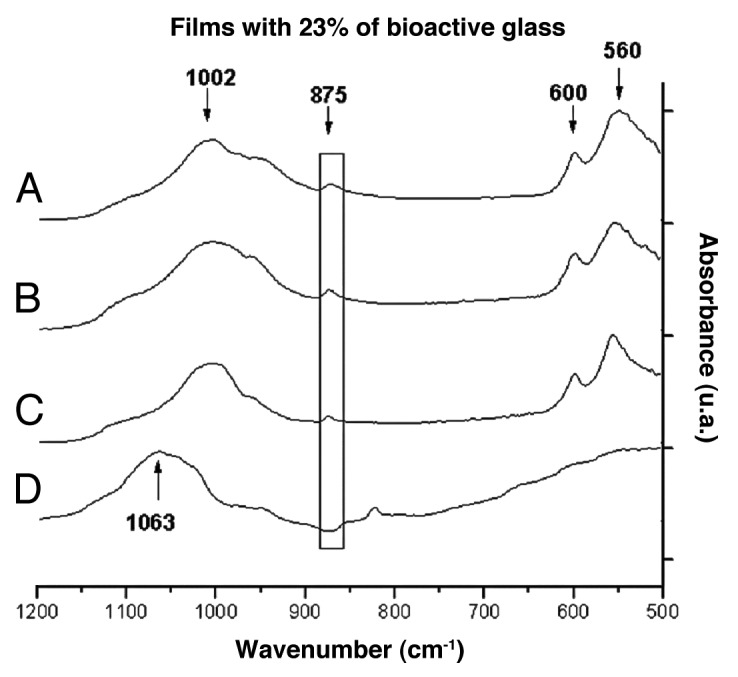

Figure 7 shows the FTIR spectra for the film with 23% bioactive glass before and after different periods of immersion. A peak displacement could be observed between 1,063 cm-1 and 1,002 cm-1, throughout the immersion time, as could the appearance of bands at 560 cm-1 and 600 cm-1 and the peak at 875 cm-1 after 1 d of immersion. These bands are indicative of the formation of carbonated hydroxyapatite on the film surface, according to the literature.18,20

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of films with 23% of bioactive glass after immersion in SBF for (A) 28, (B) 7, (C) 1 and (D) 0 d.

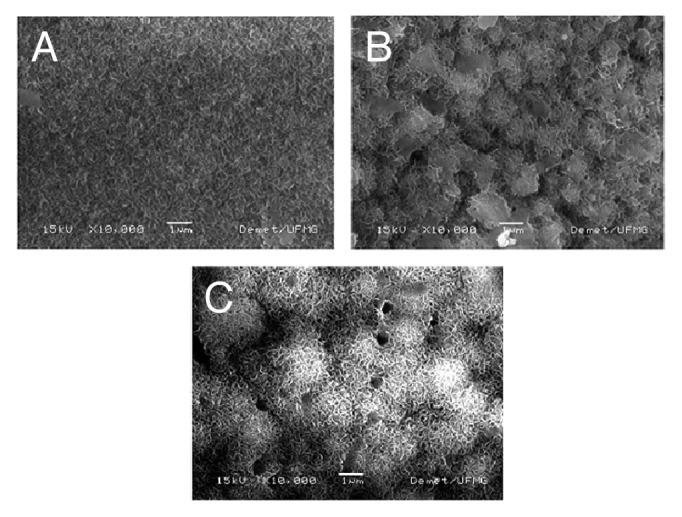

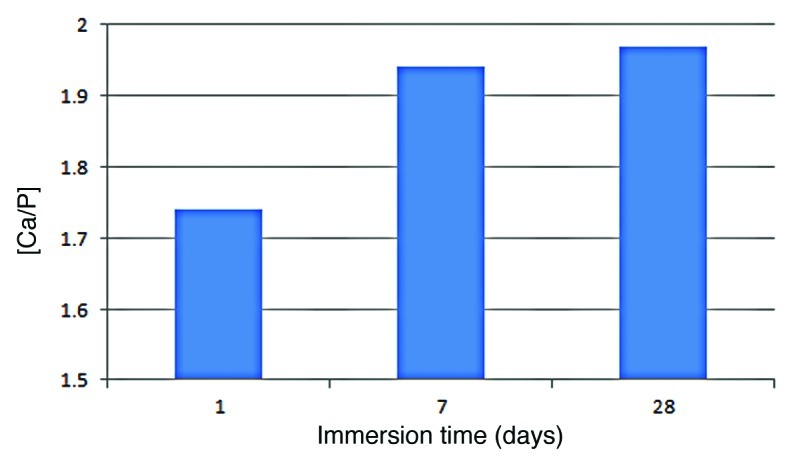

SEM images (Fig. 8) for samples containing 23% of bioactive glass show the growth of a layer in these films after only 1 d soaking into SBF. According to the morphology, it could be observed that, from days 1 to 7 and days 7 to 28, the layer gradually thickens. EDS analysis confirmed that this layer consists mostly of calcium phosphate, and the percentage by weight of phosphorus and calcium increases according to the period of soaking time into SBF. The ratio [Ca/P] increases with immersion time as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

SEM images of films with 23% of bioactive glass after soaking into SBF for (A) 1, (B) 7 and (C) 28 d (10,000X magnification).

Figure 9.

Calcium/Phosphorus ratio of the layer formed on hybrid films with 23% bioactive glass upon immersion in SBF at different time periods.

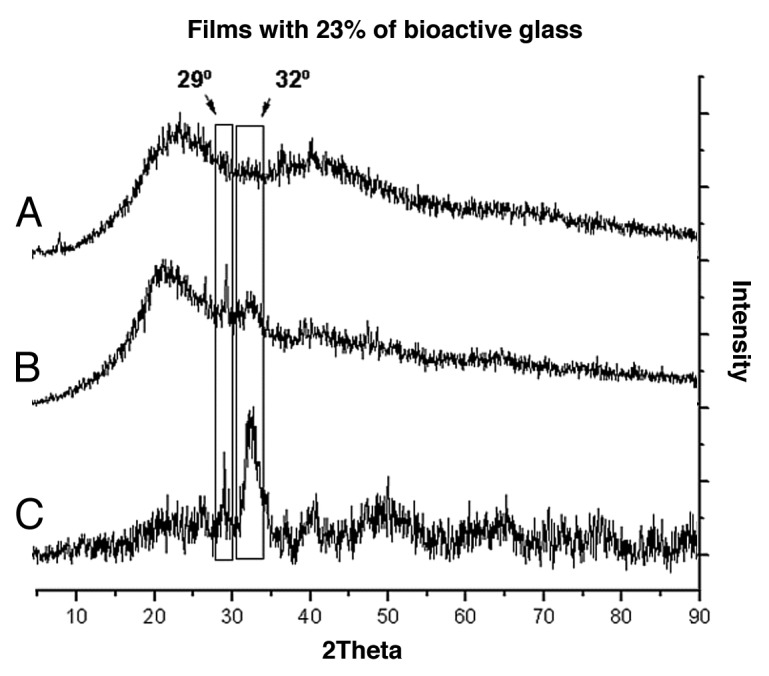

The XRD patterns (Fig. 10) of films containing 23% of bioactive glass after 1 and 28 d of immersion showed the two peaks of highest intensity found at approximately 29° and 32°, associated with plans (210) and (211), respectively. These peaks are characteristic of the crystalline phase of carbonated hydroxyapatite regarding 19–274 (JCPDS). The presence of bioactive glass was indicated by the predominant amorphous XRD pattern. By contrast, the formation of the hydroxyapatite layer by soaking in the SBF was detected by the gradual increase of XRD peaks associated with newly formed crystalline phases.

Figure 10.

Diffraction Patterns of the films with 23% of bioactive glass before (A) 0; and after (B) 1 and (C) 28 d soaking into SBF.

Considering all the results, we can say that the presence of the glass phase turns the hybrid materials bioactive, and the in vitro bioactivity increases with glass content in the hybrid. However, concerning the mechanical behavior, the film containing 23% glass showed lower mechanical properties when compared with films containing up to 17% glass. Taking both aspects into consideration, the hybrid films with 17% glass had the composition for which the addition of the inorganic phase led to an improvement of bioactivity and maintained the mechanical behavior, compared with the polymer blend.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of membranes

Films with a mass ratio of 1:3 (Chitosan:PVA) were synthesized. The composite films, containing 0%, 5%, 9%, 17% and 23% (w/w) bioactive glass made of SiO2 (60%), P2O5 (4%) and CaO (36%) were cross-linked with glutaraldehyde, representing 3.0% of the total weight of chitosan and PVA. The chitosan solution 1% (w/v) was prepared by dissolving chitosan (degree of deacetylation 85%-Sigma-Aldrich, 417963) in a 2% (w/v) acetic acid solution with stirring. The PVA solution 5% (w/v) was prepared by dissolving PVA (degree of hydrolysis DH = 80%, Sigma-Aldrich, 360627) in de-ionized water at 70 ± 2°C with mechanical stirring. The 2% (w/v) glutaraldehyde solution was obtained by diluting 25% glutaraldehyde solution (Sigma-Aldrich, 49630) in de-ionized water. Bioactive glass with composition specified before was obtained by acid hydrolysis and polycondensation of tetraethylorthosilicate (Si(OC2H5)4) (Aldrich, 131903) and triethyl phosphate (C2H5O)3PO) (Aldrich, 538728). Hydrolysis occurred by adding de-ionized water and was catalyzed by adding nitric acid. Calcium nitrate (Ca(NO3)2.4H2O) (Synth, N100601AH), was added as a precursor of CaO. The chitosan and PVA was then mixed, followed by the addition of glass. Next, NaOH 0.5 molL-1 was used to adjust the pH to 4, and, finally, glutaraldehyde was added. The solutions were poured into Petri dishes and dried at room temperature for 60 h. After, these were placed in an oven with air circulation 40 ± 2°C for 24 h.

Characterization

The films were characterized before and after their immersion in simulated body fluid (SBF), by Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis.

To evaluate the presence of chemical groups in the films before and after immersion in SBF, FTIR-ATR (attenuated total reflection), within the range of 4,000 cm-1 to 500 cm-1, was used. FTIR was performed using a Nicolet 380 from ThermoScientific using zinc selenide crystals (ZnSe). Data were collected in absorbance mode, and the spectra were normalized using the technique of dividing the intensities by the highest value of absorbance.

The morphology of the films with 0% and 23% of glass, before and after soaking in SBF, was evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was also able to evaluate the chemical composition of the films. Sample preparation consisted of coating the films with gold.

Analyses of X-ray diffraction were performed by PW 1710, Philips with 2θ ranging from 4.05° to 89.91°, with a step of 0.06°, using radiation CuKα1 (λ = 1.54060 Å).

The tensile test was conducted to evaluate the mechanical behavior of the films before immersion in SBF. The tests were performed in EMIC DL 3000 using a 500 N load cell, test speed of 5 mm/min, test temperature of 26 ± 2°C and a relative humidity of 55 ± 5%. Five samples from each composition (n = 5) were tested, with average thickness of 100 ± 30 ∝m.

In vitro study in SBF

The bioactivity tests were conducted by soaking the samples in SBF and prepared according to the standard ISO23317:2007. Samples were cut into rectangles of 10 mm x 20 mm. In each bottle, 40 mL of SBF were added in a ratio given by: Vs = Sa/10, between the surface area of the sample (Sa) in square millimeters and the volume of SBF solution (Vs) in milliliters. The samples were suspended using nylon® wires and completely immersed in SBF. The tests were performed in triplicate at five different immersion times: 1 h, 1 d, 3 d, 7 d and 28 d. The samples were maintained in a water bath at 37 ± 2°C and, after each immersion time, were removed from the SBF and dried at room temperature.

Conclusions

The FTIR analysis indicated the formation of a carbonated hydroxyapatite layer on the surface of the films through the displacement of the band between 1,024 cm-1 and 1,002 cm-1 caused by the P-O stretching-vibration as well as the appearance of the bands related to P-O bending-vibration and C-O bending-vibration of CO3-2. For the film containing 23% bioactive glass, bands appeared after the first day of immersion in SBF, however, for the films containing 9% and 17% bioactive glass, the changes occurred after 7 d of immersion. The images provided by SEM and the chemical composition provided by EDS confirmed the formation of a calcium phosphate layer on the film containing 23% glass as of the first day of immersion in SBF. According to the morphology, it could be observed that the layer gradually thickens. The results provided by XRD show a carbonated hydroxyapatite of low crystallinity. However, the peaks indicate the formation of this layer on the films containing 23% glass.

The synthesis of a bioactive hybrid as regards its behavior in vitro was achieved. Nevertheless, despite the higher in vitro bioactivity, the film containing 23% glass showed lower mechanical properties when compared with films containing up to 17% glass.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from FAPEMIG/CNPq/CAPES Brazilian Research Agencies.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ATR

attenuated total reflection

- EDS

energy dispersive spectroscopy

- FTIR

Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

- SBF

simulated body fluid

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- XRD

X-ray diffraction

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/biomatter/article/17449

References

- 1.Liao F, Chen Y, Li Z, Wang Y, Shi B, Gong Z, et al. A novel bioactive three-dimensional beta-tricalcium phosphate/chitosan scaffold for periodontal tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21:489–96. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3931-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho SM, Oliveira A, Andrade V, Leite MF, Goes A, Pereira MM. Comparative effect of the ionic products from bioactive glass dissolution on the behavior of cementoblasts, osteoblasts and fibroblasts. Key Eng Mater. 2009 doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.396-398.55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitoyannis I, Kolokuris I, Nakayama A, Yamamoto N, Aiba S. Physico-chemical studies of chitosan-poly(viny1 alcohol) blends plasticized with sorbitol and sucrose. Carbohydr Polym. 1997;34:9–19. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(97)00089-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Souza Costa-Júnior E, Pereira MM, Mansur HS. Properties and biocompatibility of chitosan films modified by blending with PVA and chemically crosslinked. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2009;20:553–61. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muzzarelli RAA, Mattioli-Belmonte M, Miliani M, Muzzarelli C, Gabbanelli F, Biagini G. In vivo and in vitro biodegradation of oxychitin-chitosan and oxypullulan-chitosan complexes. Carbohydr Polym. 2002;48:15–21. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(01)00234-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peppas NA, Mongia NK. Ultrapure poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels with mucoadhesive drug delivery characteristics. Eur Pharm Biopharm. 1997;43:51–8. doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(96)00010-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang T, Turhan M, Gunasekaran S. Selected properties of pH-sensitive, biodegradable chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel. Polym Int. 2004;53:911–8. doi: 10.1002/pi.1461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar MN, Muzzarelli RA, Muzzarelli C, Sashiwa H, Domb AJ. Chitosan chemistry and pharmaceutical perspectives. Chem Rev. 2004;104:6017–84. doi: 10.1021/cr030441b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng CM, He LZ, Zhao M, Yang D, Liu Y. Biological properties of the chitosan-gelatin sponge wound dressing. Carbohydr Polym. 2007;69:583–9. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2007.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiellini E, Corti A, D’Antone S, Solaro R. Biodegradation of poly(vinyl alcohol) based materials. Prog Polym Sci. 2009;28:963–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6700(02)00149-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mansur HS, Sadahira CM, Souza AN, Mansur AP. FTIR spectroscopy characterization of poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogel with different hydrolysis degree and chemically cross-linked with glutaraldehyde. Mater Sci Eng C. 2008;28:539–48. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2007.10.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin WC, Yu DG, Yang MC. Blood compatibility of novel poly(©-glutamic acid)/poly(vinyl alcohol hydrogels. Colloid Surface B. 2006;47:43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira MM, Jones JR, Hench LL. Bioactive glass and hybrid scaffolds prepared by the sol-gel method for bone tissue engineering. Adv Appl Ceramics. 2005;104:35–42. doi: 10.1179/174367605225011034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hench LL. The story of Bioglass. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17:967–78. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0432-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira AR, Gomide VS, Leite MF, Mansur HS, Pereira MM. Effect of polyvinyl alcohol content and after synthesis neutralization on structure, mechanical properties and cytotoxicity of sol-gel derived hybrid foams. Mater Res. 2009;12:239–44. doi: 10.1590/S1516-14392009000200021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukito D, Xue JM, Wang J. In Vitro Bioactive Assessment of 70 (wt)% SiO2-30(wt)% CaO Bioactive glasses in simulated body fluid. Mater Lett. 2005;59:3267–71. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2005.05.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xynos ID, Edgar AJ, Buttery LD, Hench LL, Polak JM. Gene-expression profiling of human osteoblasts following treatment with the ionic products of Bioglass 45S5 dissolution. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55:151–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200105)55:2<151::AID-JBM1001>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa RO, Pereira MM, Lameiras FS, Vasconcelos WL. Apatite formation on poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate)-silica hybrids prepared by sol-gel process. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:927–32. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-4427-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reis EM, Vasconcelos W, Mansur HS, Pereira MM. Synthesis and characterization of silica-chitosan porous hybrids for tissue engineering. Key Eng Mater. 2008;363:967–70. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.361-363.967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sepulveda P, Jones JR, Hench LL. In vitro dissolution of melt-derived 45S5 and sol-gel derived 58S bioactive glasses. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;61:301–11. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.