Abstract

Objective

We examined the utilization of stimulant medications for ADHD treatment among U.S. children during the period 1996–2008 to determine trends by age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, and geographical location.

Method

The 1996–2008 database of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, a public, nationally representative, annual survey of U.S. households, was analyzed for therapeutic stimulant use under age 19. The data for the year 1987 were also recalculated for reference.

Results

An estimated 3.5% (95% C.I. 3.0–4.1) of U.S. children received stimulant medication in 2008, up from 2.4% in 1996 (p<.01). Over the period 1996–2008, use increased consistently at an overall annual growth rate of 3.4%. Use increased in adolescents (annual growth: 6.5%), but did not significantly change in 6–12 year old children, and decreased in preschoolers. Use remained higher in males than females, and consistently lower in the West than in other U.S. areas. While differences by family income have disappeared over time, the use is significantly lower among racial and ethnic minorities.

Conclusions

Overall, pediatric stimulant use has been slowly but constantly increasing over the last 12 years, primarily due to greater use among adolescents. Use among preschoolers remains low and has declined over time. Important variations related to racial/ethnic background and geographical location persist, thus indicating a substantial heterogeneity in the approach to the treatment of ADHD in U.S. communities.

Keywords: stimulants, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, pharmacoepidemiology

Introduction

Stimulants such as methylphenidate and amphetamines are the most commonly used psychotropic medications in children, being widely prescribed for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (1, 2). Stimulant use increased steeply in the U.S. during the 1990s, rising from a point prevalence of 0.6% in 1987 to 2.7% in 1997 (3). In the following years, use appeared to stabilize around an estimated rate of 2.9% (95% C.I. 95% 2.5–3.3) in 2002 (4). Recent reports, however, suggest that the use of these medications may have continued to rise (5).

According to the National Health Interview Survey, approximately 9% of children aged 6–17 year-old had ever received a diagnosis of ADHD in 2006, with a wide geographical variation across the U.S. (6). These rates are consistent with the 9% lifetime prevalence of ADHD diagnosis by age 18 in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement database, which was collected between 2001 and 2004 (7). Based on the National Survey of Children’s Health, the percentage of children aged 4–17 years who had ever received a diagnosis of ADHD increased from 7.8% to 9.5% during the period between 2003 and 2007, with a 5.5% annual rate of increase (8). It is estimated that about two-thirds of the children diagnosed with ADHD receive pharmacological treatment (8).

In the last ten years, a number of new formulations of methylphenidate and amphetamines have been introduced into clinical practice, including controlled release oral and trans-dermal preparations (9). As the market for ADHD medications has expanded, concerns have been raised about the possible misuse and abuse of stimulants, especially because the increase in ADHD diagnosis has been most marked among adolescents (4, 10, 11).

Trends based on short periods of time can be imprecise and misleading. We used data from an ongoing annual, nationally-representative survey with the purpose of describing the overall trend of pediatric stimulant use in the last 12 years, with special attention to utilization by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographical location.

Methods

Data Sources

The data are drawn from the 1996 through 2008 years of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). The MEPS is a nationally representative household survey of health care use and costs conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and has been used extensively to track trends in mental health treatment in the U.S. (3, 4, 12, 13). The MEPS uses an overlapping panel design, combining two panels to produce estimates for each calendar year (with the exception of 1996 when the survey began). Households for each panel are interviewed 5 times over a two-year period. The sample for each panel is drawn from the sample of all households responding to the National Health Interview Survey in the year prior to the panel start date in MEPS. Overall response rates for the 1996 through 2008 MEPS ranged from 56.9 to 70.2 percent. Our analytic sample includes all individuals under the age of 19 in each year. Final annual sample sizes varied with the number of households sampled each year in the MEPS and ranged from 6,595 to 11,713. The MEPS sample is post-stratified to the Current Population Survey and is representative of the civilian non-institutionalized population in each year.

Data on prescription drug use in the MEPS were collected both directly from households and from a follow-back survey of all pharmacies reported by the household for which a signed permission form was obtained. Detailed information obtained from responding pharmacies (85% response rate) including National Drug Code, drug name, strength, and form for each drug fill were matched back to the prescription drug fills reported by the household. We defined stimulants to include the following compounds in various formulations: methylphenidate, dex-methylphenidate, pemoline, amphetamines, and dextroamphetamine.

The data for 1996 through 2002 match previously reported estimates from the MEPS and allow us to assess trends across a full twelve-year period (1996–2008) (4). We also replicate previously reported estimates on stimulant use for the population under age 19 using data from the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES), the predecessor to MEPS, allowing us to estimate trends over a 21-year period.

Data Analysis

We report national estimates of the annual use of stimulants for the US civilian, non-institutionalized population of children 18 years old and younger for calendar years 1996 through 2008 using MEPS and replicated estimates for 1987 using NMES. We also report changes between 1996 and 2008 for the following population subgroups: age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income relative to the federal poverty line, census region, Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) vs. non-MSAs, health insurance coverage, and impairment as measured by the Columbia Impairment Scale (16). Table 1 provides the distribution of these subgroups across the population aged 18 and under for 1996, 2002, and 2008.

Table 1.

Distribution of Population Characteristics, 1996, 2002, 2008

| Sample Size | Percentage Distribution (weighted) | 1996–2008 Difference |

2002–2008 Difference |

1996–2002 Difference |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1996 | 2002 | 2008 | 1996 | 2002 | 2008 | t-stat | p-val | t-stat | p-val | t-stat | p-val | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 0–5 | 2,018 | 3,455 | 3,046 | 32 (30–33) | 30 (29–31) | 31 (30–33) | –0.39 | 0.700 | 1.06 | 0.290 | −1.43 | 0.154 |

| 6–12 | 2,577 | 4,498 | 3,588 | 37 (36–39) | 37 (36–38) | 36 (35–38) | −0.47 | 0.636 | −0.57 | 0.567 | 0.05 | 0.962 |

| 13–18 | 2,000 | 3,760 | 3,027 | 31 (30–33) | 33 (31–34) | 33 (32–34) | 0.85 | 0.396 | −0.50 | 0.615 | 1.36 | 0.173 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 3,358 | 6,022 | 5,088 | 52 (50–53) | 51 (50–52) | 51 (50–52) | −0.60 | 0.546 | 0.05 | 0.961 | −0.68 | 0.499 |

| Female | 3,237 | 5,691 | 4,653 | 48 (47–50) | 49 (48–50) | 49 (48–50) | 0.60 | 0.546 | −0.05 | 0.961 | 0.68 | 0.499 |

| Race/Ethnicity (mutually exclusive categories) | ||||||||||||

| White | 3,370 | 5,155 | 3,302 | 65 (62–68) | 60 (58–62) | 57 (54–60) | −4.09 | <0.001 | −1.93 | 0.055 | −2.77 | 0.006 |

| African American | 1,051 | 2,166 | 2,300 | 16 (13–18) | 16 (14–17) | 16 (14–17) | 0.20 | 0.872 | 0.00 | 0.997 | 0.25 | 0.804 |

| Hispanic | 1,933 | 3,828 | 3,455 | 15 (13–17) | 18 (17–20) | 22 (19–25) | 3.73 | <0.001 | 2.13 | 0.034 | 2.97 | 0.003 |

| Other | 241 | 564 | 604 | 4 (3–5) | 6 (5–7) | 5 (4–6) | 1.17 | 0.071 | −0.27 | 0.784 | 1.60 | 0.110 |

| Family income relative to federal poverty line | ||||||||||||

| Poor/Near Poor (<125%) | 2,237 | 3,730 | 3,693 | 26 (24–29) | 22 (21–24) | 25 (23–27) | −0.93 | 0.354 | 1.73 | 0.085 | −2.77 | 0.006 |

| Low/Middle (125–400%) | 3,090 | 5,818 | 4,386 | 51 (48–53) | 50 (49–52) | 49 (47–52) | −0.73 | 0.464 | −0.67 | 0.504 | −0.20 | 0.845 |

| High Income (>400%) | 1,268 | 2,165 | 1,582 | 26 (24–28) | 27 (26–29) | 26 (24–28) | 1.67 | 0.096 | −0.98 | 0.329 | 2.76 | 0.006 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Northeast | 1,271 | 1,761 | 1,423 | 19 (16–21) | 18 (16–20) | 17 (15–19) | −1.07 | 0.285 | −0.77 | 0.442 | −0.34 | 0.733 |

| Midwest | 1,346 | 2,165 | 1,950 | 23 (21–26) | 22 (20–25) | 22 (19–24) | 0.96 | 0.336 | −0.52 | 0.604 | −0.59 | 0.556 |

| South | 2,264 | 4,397 | 3,602 | 35 (31–38) | 35 (33–38) | 37 (35–40) | 1.30 | 0.195 | 1.04 | 0.297 | 0.47 | 0.639 |

| West | 1,714 | 3,390 | 2,686 | 24 (21–26) | 24 (21–27) | 24 (22–27) | 0.33 | 0.742 | −0.02 | 0.984 | 0.42 | 0.676 |

| Urban | ||||||||||||

| non-MSAa | 1,417 | 2,214 | 1.324 | 20 (18–23) | 18 (16–19) | 15 (13–18) | −2.50 | 0.013 | −1.30 | 0.193 | −2.05 | 0.040 |

| MSA | 5,178 | 9,499 | 8,317 | 79 (77–82) | 82 (80–84) | 84 (81–87) | 2.50 | 0.013 | 1.30 | 0.193 | 2.05 | 0.040 |

| Insurance | ||||||||||||

| Any Private | 3,979 | 6,354 | 4,501 | 69 (66–71) | 66 (64–67) | 61 (58–63) | −4.45 | <0.001 | −3.19 | 0.002 | −2.20 | 0.028 |

| Public Only | 1,750 | 4,265 | 4,358 | 20 (18–23) | 26 (25–28) | 31 (29–33) | 6.83 | <0.001 | 3.26 | 0.001 | 4.99 | <0.001 |

| Uninsured | 866 | 1,094 | 802 | 11 (10–12) | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–9) | −3.28 | 0.001 | 0.29 | 0.774 | −4.28 | <0.001 |

| Columbia Impairment Scale (ages 5–17) | ||||||||||||

| Not impaired (CIS< 16) | 3,970 | 7,242 | 5,852 | 87 (85–89) | 87 (86–88) | 88 (87–89) | 1.43 | 0.153 | 0.01 | 0.993 | 1.49 | 0.136 |

| Impaired (CIS>=16) | 619 | 1,007 | 746 | 13 (11–15) | 12 (11–13) | 12 (11–13) | −1.43 | 0.153 | −0.01 | 0.993 | −1.49 | 0.136 |

Source: Author’s Calculations from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 1996–2008

Note: 95 percent confidence intervals in parentheses.

Metropolitan Statistical Area

MEPS sampling weights, which adjust for the stratified sample design and non-response, are used throughout the analyses. We use two-tailed t-tests, computed with these weights and accounting for the complex sample design and correlation across individuals, to assess changes in stimulant use between 1996 and 2008, between 1996 and 2002, and, most recently, between 2002 and 2008. Logistical regression analysis is used to further examine the sociodemographic correlates of stimulant use among children age 5–17 for whom the Columbia Impairment Scale measure was available, pooling the years 2006 through 2008 to increase power to detect differences.

We have 90% power to detect an average 0.20 percentage point change per year over five-year intervals at the .05 level. This is a smaller average increase than was observed between 1987 and 1997 (0.26 percentage points). We report all statistical tests based on annual estimates, but also recomputed all tests pooling data for consecutive years to test the robustness of the results.

All statistical analyses and tests were performed using STATA/MP Version 11.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

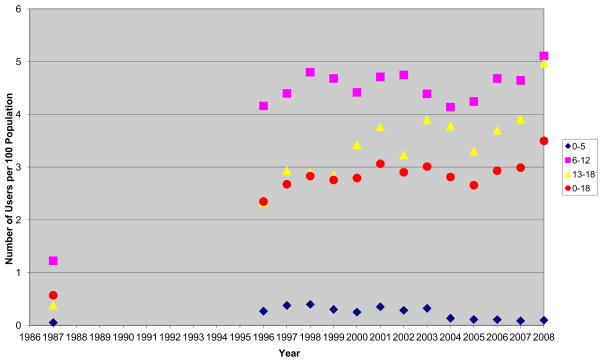

An estimated 2.8 million (95% C.I. 2.3–3.2) children (subjects under age 19 years) received stimulant medication in 2008. The utilization rate was 3.5% (95% C.I. 3.0–4.1) in 2008, representing a statistically significant increase from 1996 (2.4%; 95% C.I. 1.8–2.9) (Table 2 and Figure 1). This translates into a compound annual growth rate of 3.4% for the period 1996 to 2008. This growth was substantially slower than the annual growth rate of 17.0% between 1987 and 1996.

Table 2.

Trends in Stimulant Use in the U.S Population 18 Years and Younger, 1996–2008

| 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 1996–2008 Difference |

2002–2008 Difference |

1996–2002 Difference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| t-stat | p-value | t-stat | p-value | t-stat | p-value | ||||||||||||||

| Number of users (millions) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 2.0 (1.7–2.3) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | 2.1 (1.6–2.7) | 2.4 (2.0–2.8) | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 2.3 (2.0–2.7) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | 2.1 (2.1–2.9) | 2.3 (1.7–2.4) | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | 2.8 (2.3–3.2) | 3.10 | 0.002 | 1.81 | 0.072 | 1.72 | 0.085 |

| 0–5 | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.1) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | −1.14 | 0.256 | −1.22 | 0.221 | −0.04 | 0.967 |

| 6–12 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.4 (1.0–1.7) | 1.4 (1.0–1.7) | 1.3 (0.9–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) | 1.3 (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.42 | 0.156 | 0.59 | 0.554 | 1.02 | 0.310 |

| 13–18 | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 3.93 | <.001 | 2.57 | 0.010 | 2.06 | 0.040 |

| Percent with Use | 2.4 (1.8–2.9) | 2.7 (2.3–3.1) | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 3.1 (2.6–3.5) | 2.9 (2.5–3.3) | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) | 2.8 (2.4–3.3) | 2.7 (2.3–3.1) | 2.9 (2.5–3.4) | 3.0 (2.5–3.5) | 3.5 (3.0–4.1) | 3.00 | 0.003 | 1.70 | 0.089 | 1.61 | 0.109 |

| 0–5 | 0.3 (0.0–0.5) | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 0.4 (0.1–0.7) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.3 (0.0–0.5) | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 0.3 (0.0–0.6) | 0.3 (0.0–0.6) | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | −1.18 | 0.238 | −1.27 | 0.205 | 0.08 | 0.940 |

| 6–12 | 4.2 (3.2–5.2) | 4.4 (3.6–5.2) | 4.8 (3.7–5.9) | 4.7 (3.6–5.8) | 4.4 (3.5–5.3) | 4.7 (3.9–5.5) | 4.8 (3.9–5.6) | 4.4 (3.5–5.3) | 4.1 (3.2–5.1) | 4.2 (3.4–5.1) | 4.7 (3.7–5.6) | 4.6 (3.8–5.5) | 5.1 (4.1–6.1) | 1.29 | 0.197 | 0.54 | 0.591 | 0.89 | 0.373 |

| 13–18 | 2.3 (1.5–3.1) | 2.9 (2.2–3.7) | 2.9 (2.0–3.8) | 2.9 (2.1–3.7) | 3.4 (2.4–4.4) | 3.8 (2.9–4.7) | 3.2 (2.6–3.9) | 3.9 (3.0–4.8) | 3.8 (2.8–4.8) | 3.3 (2.5–4.1) | 3.7 (2.8–4.6) | 3.9 (3.0–4.8) | 4.9 (3.9–6.1) | 3.85 | <.001 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 1.81 | 0.071 |

| Total Population (millions) | 75.3 | 75.6 | 76.5 | 76.7 | 76.7 | 77.0 | 77.0 | 77.2 | 77.3 | 77.4 | 78.4 | 78.3 | 79.0 | ||||||

| 0–5 | 23.9 | 23.8 | 23.8 | 23.9 | 24.1 | 23.7 | 23.3 | 23.1 | 23.3 | 23.8 | 24.4 | 24.3 | 24.7 | ||||||

| 6–12 | 27.9 | 28.3 | 28.4 | 29.3 | 28.5 | 28.5 | 28.6 | 28.7 | 28.2 | 27.9 | 28.0 | 28.3 | 28.9 | ||||||

| 13–18 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 24.4 | 23.5 | 24 | 24.8 | 25.1 | 25.4 | 25.8 | 25.7 | 25.9 | 25.6 | 25.4 | ||||||

| Sample Size | 6,595 | 10,285 | 7,282 | 7,235 | 7,286 | 9,710 | 11,713 | 10,528 | 10,297 | 10,172 | 10,152 | 8,968 | 9,661 | ||||||

| 0–5 | 2,018 | 3,081 | 2,116 | 2,158 | 2,221 | 2,924 | 3,455 | 3,194 | 3,177 | 3,114 | 3,103 | 2,674 | 3,046 | ||||||

| 6–12 | 2,577 | 4,008 | 2,844 | 2,872 | 2,851 | 3,733 | 4,498 | 3,992 | 3,898 | 3,825 | 3,792 | 3,389 | 3,588 | ||||||

| 13–18 | 2,000 | 3,196 | 2,322 | 2,205 | 2,214 | 3,053 | 3,760 | 3,342 | 3,222 | 3,233 | 3,257 | 2,905 | 3,027 | ||||||

Source: Authors’ Calculations from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 1996–2008

Figure 1. Trends in Prevalence of Stimulant Use in the U.S. Population 18 years and Younger 1987–2008.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey and the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 1996–2008.

Across all of the years of observation (1987, 1996–2008), use was highest among 6–12 year olds. In this age group, use was 4.2% (95% C.I. 3.2–5.2) in 1996 and 5.1% (95% C.I. 4.1–6.1) in 2008, with no statistically significant change. Over the same period, use among 13–18 year olds increased at an annual rate of 6.5%, from 2.3% (95% C.I. 1.5–3.1) in 1996 to 4.9% (95% C.I. 3.9–6.1) in 2008. Use under 6 years of age remained very low (0.1% from 2004 onwards), with a statistically significant decrease from the period before 2004 to the period afterwards (t=3.71, p< .001).

Use was more than 3-fold greater in males than in females in 2008, thus returning to the same male:female ratio as in 1996 (Table 3). The difference between males and females had narrowed between 1996 and 2002 as females increased use at a faster rate than males, but then widened again between 2002 and 2008 as males increased use and females did not.

Table 3.

Stimulant Use by Selected Population Characteristics, 1996, 2002, 2008

| Percent with Use | 1996–2008 Difference |

2002–2008 Difference |

1996–2002 Difference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 1996 | 2002 | 2008 | t-statistic | p-value | t-statistic | p-value | t-statistic | p-value | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 0–5 | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.3 (0.0–0.6) | 0.1 (0.0–0.2) | −1.18 | 0.238 | −1.27 | 0.205 | 0.08 | 0.940 |

| 6–12 | 4.2 (3.2–5.2) | 4.8 (3.9–5.6) | 5.1 (4.1–6.1) | 1.29 | 0.197 | 0.54 | 0.591 | 0.89 | 0.373 |

| 13–18 | 2.3 (1.5–3.1) | 3.2 (2.6–3.9) | 4.9 (3.9–6.1) | 3.85 | <.001 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 1.81 | 0.071 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 3.5 (2.6–4.4) | 4.0 (3.4–4.7) | 5.3 (4.4–6.2) | 2.76 | 0.006 | 2.25 | 0.025 | 0.89 | 0.372 |

| Female | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) | 1.50 | 0.135 | −0.41 | 0.680 | 1.93 | 0.054 |

| Race/Ethnicity (mutually exclusive categories) | |||||||||

| White | 2.9 (2.3–3.6) | 3.6 (3.0–4.2) | 4.4 (3.5–5.2) | 2.53 | 0.012 | 1.34 | 0.180 | 1.46 | 0.144 |

| African American | 1.9 (0.9–3.0) | 2.2 (1.2–3.2) | 3.0 (2.1–3.8) | 1.52 | 0.129 | 1.15 | 0.252 | 0.39 | 0.694 |

| Hispanic | 0.7 (0.3–1.1) | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 2.1 (1.5–2.7) | 3.75 | <.001 | 1.63 | 0.103 | 2.16 | 0.031 |

| Other | 0.7 (0.0–1.8) | 1.7 (0.0–3.2) | 1.6 (0.0–3.0) | 0.95 | 0.342 | −0.09 | 0.926 | 0.99 | 0.322 |

| Family income relative to federal poverty line | |||||||||

| Poor/Near Poor (<125%) | 2.1 (1.1–3.0) | 2.6 (1.8–3.4) | 3.6 (2.6–4.7) | 2.27 | 0.023 | 1.62 | 0.106 | 0.88 | 0.380 |

| Low/Middle (125–400%) | 2.4 (1.8–3.1) | 3.2 (2.5–3.8) | 3.3 (2.6–4.0) | 1.79 | 0.074 | 0.30 | 0.767 | 1.58 | 0.115 |

| High Income (>400%) | 2.5(1.5–3.5) | 2.7 (1.9–3.4) | 3.7 (2.5–4.9) | 1.56 | 0.120 | 1.49 | 0.138 | 0.26 | 0.792 |

| Region | |||||||||

| Northeast | 1.8 (1.1–2.5) | 2.7 (1.6–3.9) | 4.6 (3.0–6.1) | 3.22 | 0.001 | 1.88 | 0.060 | 1.49 | 0.138 |

| Midwest | 2.6 (1.3–3.9) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.9 (2.8–5.1) | 1.46 | 0.145 | 1.19 | 0.235 | 0.43 | 0.668 |

| South | 3.2 (2.3–4.2) | 3.4 (2.7–4.1) | 4.0 (2.9–5.1) | 1.05 | 0.294 | 0.96 | 0.339 | 0.24 | 0.812 |

| West | 1.2 (0.4–2.0) | 2.2 (1.3–3.1) | 1.6 (1.0–2.1) | 0.71 | 0.477 | −1.18 | 0.239 | 1.65 | 0.100 |

| Urban | |||||||||

| non-MSA | 2.5 (1.6–3.4) | 3.2 (2.3–4.0) | 3.5 (2.2–4.9) | 1.22 | 0.224 | 0.43 | 0.666 | 1.01 | 0.311 |

| MSA | 2.3 (1.7–2.9) | 2.9 (2.4–3.6) | 3.5(2.9–4.1) | 2.71 | 0.007 | 1.69 | 0.092 | 1.31 | 0.191 |

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Any Private | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) | 3.0 (2.5–3.5) | 3.4 (2.7–3.6) | 2.26 | 0.024 | 0.97 | 0.334 | 1.44 | 0.150 |

| Public Only | 3.0 (1.7–4.3) | 3.3 (2.5–4.2) | 4.3 (3.4–5.2) | 1.62 | 0.106 | 1.52 | 0.128 | 0.40 | 0.687 |

| Uninsured | 0.7 (0.1–1.2) | 0.9 (0.0–1.7) | 1.3 (0.0–2.5) | 0.85 | 0.394 | 0.55 | 0.583 | 0.30 | 0.761 |

| Columbia Impairment Scale (ages 5–17) | |||||||||

| Not impaired (CIS< 16) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 3.0 (2.4–3.6) | 1.80 | 0.072 | 0.62 | 0.537 | 1.32 | 0.188 |

| Impaired (CIS>=16) | 10.0 (6.9–13.1) | 13.9 (11.0–16.6) | 18.1 (14.4–21.8) | 3.28 | 0.001 | 1.80 | 0.073 | 1.85 | 0.064 |

Source: Author’s Calculations from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 1996–2008

Note: 95 percent confidence intervals in parentheses.

Use remained consistently greater among non-Hispanic White children (4.4% in 2008) than among African American (3.0%) or Hispanic (2.1%) children (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Stimulant Use among 5–17 Year Olds, 2006–2008 (N=19,950)

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI

|

p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | |||||

| 5–12 (omitted) | |||||

| 13–17 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 1.12 | 0.333 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2.62 | 2.05 | 3.35 | <.001 | |

| Female (omitted) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity (mutually exclusive categories) | |||||

| White (omitted) | |||||

| African American | 0.64 | 0.49 | 0.85 | 0.002 | |

| Hispanic | 0.70 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.052 | |

| Other | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.86 | 0.016 | |

| Family income relative to federal poverty line | |||||

| Poor/Near Poor (<125%) | |||||

| Low/Middle (125–400%) | 0.80 | 0.54 | 1.17 | 0.243 | |

| High Income(>400%) | 0.78 | 0.58 | 1.05 | 0.106 | |

| Region | |||||

| Northeast (omitted) | |||||

| Midwest | 0.98 | 0.70 | 1.37 | 0.904 | |

| South | 1.09 | 0.81 | 1.47 | 0.582 | |

| West | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.64 | <.001 | |

| Urban | |||||

| non-MSA (omitted) | |||||

| MSA | 1.10 | 0.83 | 1.46 | 0.497 | |

| Insurance | |||||

| Any Private | 1.38 | 0.71 | 2.68 | 0.346 | |

| Public Only | 1.88 | 1.00 | 3.54 | 0.051 | |

| Uninsured (omitted) | |||||

| Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS, age 5–17) | |||||

| Not impaired (CIS< 16) | |||||

| Impaired (CIS≥16) | 6.83 | 5.43 | 8.58 | <.001 | |

| Year | |||||

| 2006 (omitted) | |||||

| 2007 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 1.24 | 0.671 | |

| 2008 | 1.14 | 0.91 | 1.44 | 0.265 | |

Source: Author’s Calculations from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 2006–2008

Use remained similar across all income groups in the period 1996–2008 as each group experienced similar patterns of increase (Table 3). Subjects without insurance, however, continued to have lower utilization (1.3% in 2008) than those with private (3.4%) or public (4.3%) insurance. Among the insured, children with public coverage tended to have greater utilization than those with private coverage (odds ratio=1.36, t=2.14, p=.016).

Significant differences in use were found across geographical areas of the U.S (Table 3). Rates of utilization increased substantially in the Northeast (from 2.7% in 2002 to 4.6% in 2008 with much of the spike coming in the last year). In contrast, the West maintained a consistently lower rate of utilization, with no increase in recent years (1.2 % in 1996, 2.2% in 2002, and 1.6% in 2008).

As stimulants, though constituting the first line pharmacological treatment of ADHD, are not the only medications available for children with this disorder, the pediatric use of other commonly prescribed ADHD medications was estimated using the MEPS database for most recent years. In 2007/2008, the mean use of clonidine and guanfacine combined was 0.3% (95% C.I. 0.2–0.4) overall, 0.6% (95% C.I. 0.3–0.8) in 6–12 year olds, and 0.3% (95% C.I. 0.1–0.5) in 13–18 year olds. Most (80.2%, 95% C.I. 67.1–93.3) of the clonidine/guanfacine users also used stimulants during the previous 12 months (though not necessarily concurrently). The mean use of atomoxetine in 2007/2008 was 0.6% (95% C.I. 0.4–0.7) overall, 0.8% (95% C.I. 0.5–1.1) in 6–12 year olds, and 0.8% (95% C.I. 0.5–1.0) in 13–18 year olds. One-third of these users (32.7%; 95% C.I. 67.1–93.3) also used stimulants during the year. Atomoxetine use was 0.9% (95% C.I. 0.7–1.0) in 2004/2005, which was significantly higher than in 2007/2008 (t=2.44, p=.015).

Discussion

These data, which are based on a nationally representative survey, show that the pediatric use of stimulants has continued to grow at the same pace since the mid-1990s. This relatively slow growth is in sharp contrast to the rapid increase that occurred between the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. However, the overall growth rate for children under age 19 mask important changes that have occurred within different age groups. In particular, stimulant use increased among 13–18 year olds in the period 2002–2008, with use rates converging with those of 6–12 year olds. In contrast, use has declined in preschoolers.

Children from racial and ethnic minority groups have increased the use of stimulants, which, however, remains lower than among non-Hispanic White children. In addition, while females tend to use more stimulants now than ten years ago, boys still retain a 3-fold higher utilization rate, which is consistent with the higher prevalence of ADHD in males (6–8). Finally, significant differences by U.S. geographical location persist, with the West having significantly lower use.

If one compares these estimated rates of utilization of stimulant medication with the estimated prevalence of the ADHD diagnosis in the community (6–8), it appears that most children diagnosed with ADHD are not treated with stimulants. This may not be unexpected when considering that about half of those diagnosed present only with mild symptoms (6–8), and that other treatments, including both psychosocial and non-stimulant medications, are available. In the absence of biological markers for ADHD, the validity of community diagnoses is uncertain, and the MEPS database does not allow diagnostic validity to be examined, even though it represents an ecologically valid estimate of the prevalence of community diagnoses. In any case, the data show that stimulant use is higher in children with significant functional impairment, as indicated by the Columbia Impairment Scale (Tables 3 and 4), further supporting the notion that these medications tend to be prescribed for the more severe forms of the disorder.

The significant increase in stimulant utilization among racial and ethnic minorities and low income families indicates an increased recognition of ADHD and acceptance of its pharmacological treatment also by the groups where disparities in mental health services have traditionally existed. But the persistence of differences in use among racial and ethnic groups also indicates that social and cultural factors continue to play a significant role in ADHD treatment utilization. Parents of Hispanic and African American children are less likely to report ADHD than parents of white children, and these differences were not accounted for by health or socioeconomic variables, such as birthweight, income, or insurance coverage (17).

The continuous, steep increase in stimulant utilization among adolescents likely reflects the recent realization that ADHD tends to persist in puberty, causing significant functional impairment (18, 19). Data from the U.K. document a steep increase in ADHD medication prescribing for youth over the years 1999–2006, thus indicating that this phenomenon is not limited to the U.S. (20). The increasing use in this age group does little to assuage the concerns raised about the potential for misuse and diversion of these medications (11).

An age group in which use has remained extremely low, and has actually declined over the twelve-year period 1996–2008, is that of the preschoolers (Table 2). In early 2000, much concern was raised about use of stimulants by young children (21). Subsequently, a controlled clinical trial showed that methylphenidate is effective in preschoolers with ADHD, but also causes more adverse effects than in school-age children (22). These data indicate that, in clinical practice, stimulants are seldom used in children under age 6, and the trend has been towards even lower use.

The significant differences in use across geographical areas of the U.S. are consistent with previous reports (24), and document a substantial variability in the approach to ADHD, which likely reflects differences in treatment preferences across the country that deserve further inquiry. Differences in health care organization and delivery in the West compared with the rest of the U.S. may account for some of the observed discrepancy. However, the lower use of stimulant medication in the West does not seem to be paralleled by a lower pediatric use of other psychiatric medications, such as antidepressants (25).

Several methodological limitations must be taken into account when interpreting these data. Self-report surveys such as the MEPS rely on the responders’ ability and willingness to accurately recall information. Recall and reporting biases could result in under reporting and consequently underestimating use. While the MEPS is designed to make nationally representative estimates using probability-based sampling, the adjustments made for non-response may not completely eliminate the potential for non-response bias. The MEPS does not include sufficient information for determining the validity of the reported diagnosis of ADHD. Yet, the validity of the MEPS data is supported by their consistency with data on drug expenditures from other sources (26). Another limitation is the lack of detail and statistical power in the database regarding non-stimulants or the combined use of medications in children, a practice that has become increasingly common (27). However, based on available data, it appears that the proportion of atomoxetine users is small and has decreased, while most children using clonidine or guanfacine are also prescribed stimulants.

In conclusion, these data document an overall slow and constant increase over the last 12 years in stimulant medication utilization by children in the U.S., but with a steep growth in adolescents, no statistically significant change in children age 6–12 years, and a decline in preschoolers. Important variations in use related to racial/ethnic background and geographical location persist, thus indicating substantial heterogeneity in the approach to ADHD in the community.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Disclosure: The opinions and assertions contained in this report are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute of Mental Health, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Samuel H. Zuvekas, Center for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 540 Gaither Road, Rockville, MD 20850

Benedetto Vitiello, Email: bvitiell@mail.nih.gov, Division of Services and Intervention Research, National Institute of Mental Health, 6001 Executive Blvd., Bethesda, MD 20892-9633, Phone: 301-443-4283, Fax: 301-443-4045

References

- 1.Zito JM, Safer DJ, DosReis S, Gardner JF, Magder L, Soeken K, Boles M, Lynch F, Riddle MA. Psychotropic practice patterns for youth: a 10-year perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(1):17–25. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pliszka S AACAP Workgroup on Quality Issues. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894–921. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Marcus SC, Jensen PS. National trends in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Jun;160(6):1071–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuvekas SH, Vitiello B, Norquist NS. Recent trends in stimulant medication use among U.S. children. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:579–585. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheffler RM, Hinshaw SP, Modrek S, Levine P. The global market for ADHD medications. Health Affairs. 2007;26:450–457. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disability: United States, 2004–2006. National Center for Health Statistics. [access verified March 9, 2011];Vital Health Stat. 2008 10(237) DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 2008-1565. (Available at Website: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/Sr10_237.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visser SN, Bitsko RH, Danileson ML, Perou R. Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children – United States, 2003 and 2007. MMWR. 2010;59(44):1439–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swanson JM, Volkow ND. Psychopharmacology: concepts and opinions about the use of stimulant medications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50:180–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanson JM, Volkow ND. Increasing use of stimulants warns of potential abuse. Nature. 2008;453:586. doi: 10.1038/453586a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, Sgambati S, Rotrosen J, Sawtelle R, Utzinger L, Fusillo S. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):21–31. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Rizzo J. Racial and ethnic disparities in use of psychotherapy: evidence from US national survey data. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:364–372. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:848–856. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moeller JF, Stagnitti MN, Horan E, Ward P, Kieffer N, Hock E. Outpatient prescription drugs; data collection and editing in the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (HC-010A) Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. MEPS Methodology Report No. 12. AHRQ Pub. No. 01-0002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stagnitti MN, Beauregard K, Solis A. Methodology Report No 23. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Nov, 2008. Design, Methods, and Field Results of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Medical Provider Component (MEPS MPC)—2006 Calendar Year Data. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bird H, Schwab-Stone M, Andrews H, et al. Global measures of impairment for epidemiologic and clinical use with children and adolescents. J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1996;6:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD and LD in young school-age children: parental reports in the National Health Interview Survey. Public Health Reports. 2005;120:383–392. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SS, Lahey BB, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Few preschool boys and girls with ADHD are well-adjusted during adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008 Apr;36(3):373–83. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilens TE, Spencer TJ. Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(5):97–109. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy S, Asherson P, Coghill D, Hollis C, Murray M, Potts L, Sayal K, de Soysa R, Taylor E, Williams T, Wong ICK. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: treatment discontinuation in adolescents and young adults. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:273–277. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA. 2000;283:1025–1030. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenhill LL, Abikoff H, Chuang S, Cooper T, Cunningham C, Davies M, Ghuman J, Kollins S, McCracken JT, McGough J, Posner K, Riddle MA, Skrobala A, Swanson A, Vitiello B, Wigal S, Wigal T. Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1284–1293. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000235077.32661.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox ER, Motheral BR, Henderson RR, Mager D. Geographic variation in the prevalence of stimulant medication use among children 5 to 14 years old: results from a commercially insured US sample. Pediatrics. 2003;111:237–243. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vitiello B, Zuvekas S, Norquist DG. National estimates of antidepressant medication use among U.S. children in 1997–2002. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:271–279. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000192249.61271.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sing M, Banthin JS, Selden TM, Cowan CA, Keehan SP. Reconciling Medical Expenditure Estimates from the MEPS and NHEA. Health Care Financing Rev. 2002;28 (1):25–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]