Abstract

Aim:

This experimental study was designed to focus on the effects of bleaching on toothbrush abrasion in three types of composites with different filler size.

Materials and Methods:

Forty eight disks were prepared from three types of composite and divided into 6 groups. In the first three groups the abrasion test was done. The remaining groups were bleached and the abrasion test was performed. The weight of the samples before and after abrasion was measured. Statistical analysis was done with one-way ANOVA and Duncan test.

Results:

There was a significant difference in abrasion of composites with different filler size (P < 0.05). The most amount of abrasion was observed in Z100 after being bleached. An increase in abrasion was noticed in all three types of tested composite after bleaching.

Conclusion:

According to the findings, it is suggested to use a nano filled resin composite for restoration if the bleaching treatment is required.

Keywords: Bleaching, carbamide peroxide, resin composite, toothbrush abrasion

INTRODUCTION

Many products and different techniques have been presented since introducing the first commercial product for bleaching. Although there have been a lot of advances in this field, there are still vague points and unanswered questions on tooth bleaching.[1]

For the time, two basic bleaching techniques include in-office (professional) and home bleaching technique. Since introducing home bleaching technique by Haywood and Hayman in 1989, this type of treatment called the attention of dentists and patients because of clinical efficiency and the ease of the work.[2] This procedure, mostly done with carbamide peroxide, is usually considered safe and ideal.[2,3] It also has some privileges: Patients can use it by themselves, less time is necessary to be spent at the clinic; it is characterized by more safety, fewer side effects and fewer expenses.[4]

However, despite all the claims that this technique has no side effects, this treatment is expected to have some effects on different substrates in the mouth because of its chemical nature.[5] Some of the researchers have reported some changes in enamel after the use of bleaching materials including deionization,[6] the increase of superficial roughness,[7] greater accumulation of bacteria and a change in hardness and color.[8]

There are controversies in the results of the studies on the effect of bleaching on restorative materials. Some studies showed no effects for bleaching on dental materials (such as resin composite, glass ionomer or luting cements).[9] However, some other studies showed side effects for bleaching materials. The reactions influencing resin composite restorations may be increase of superficial roughness, change of color, presence of cleft, changes in micro hardness and consequently increase of micro leakage.[9,10] Change in superficial morphology, physical and chemical properties of the resin composites can be mentioned as other effects of bleaching on resin composite.[11]

However, there have been lots of detailed studies on micro hardness and superficial roughness. There are few reports on the effect of the bleaching materials on the abrasion behavior of composites. The aim of the present study was to research the effect of a bleaching material on tooth brush abrasion in three different resin composites with different filler size.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty eight disks were fabricated of three different types of resin composites; Z100 (3M, USA), Z250 (3M, USA) and Suprim (3M, USA).

To produce composite samples, a cylindrical mold (diameter 10 mm, height 6 mm) was filled with resin composite. The mold was compacted on both sides by two glass slabs and the composite was light cured on each side (top and bottom) for 40 seconds with the intensity of 400 mv/cm2 by QTH light curing device (Astralis 7, Vivadent, Liechtenstein). Samples were polished by silicon carbide paper (800 grit) to eliminate the resin-rich surface. The bottom surface of each sample was marked by a round bur. Samples stored in distilled water at 37°C for two weeks. Each sample was weighed at the level of 10-4 gram with a precise scale (CR200, ANS, Japan) for 3 times. The average was considered as the weight of the sample as the baseline weight.

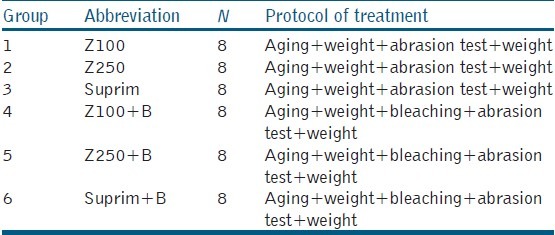

Sixteen disks were made from each of the resin composites (totally 48 disks). These samples randomly divided into 6 groups as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental groups

The samples of the control groups (groups 1, 2 and 3) were exposed to simulated brushing procedure. The samples of the testing groups (groups 4, 5 and 6) were exposed to home bleaching treatment and then transferred to tooth brush simulator machine.

For brushing step, samples were put in acrylic holders. The acrylic bases were transferred to toothbrush simulator machine. A toothpaste (Crest Complete, Crest, Germany) and water in proportion of one to four was mixed and poured into the machine so that the mixture would cover the samples for 1 cm.

Head of a toothbrush (Classic, Jordan, Malaysia) with a medium coarseness was adjusted over the sample in the jig of the toothbrush simulator machine. The radius of the movement of the toothbrush was 15 mm with a forward and backward motion. The force applied during brushing-test was 300 grams (the weight of the toothbrush and the jig together). The jig moved with the speed of 190 strokes per minute and totally 6000 strokes were performed for each sample.

Then the samples were taken out of the machine, washed with distilled water and dried with absorbing paper. The final weight of the samples was recorded as the same of the baseline.

The samples in groups 4, 5 and 6 received the bleaching treatment. The samples were exposed to carbamide peroxide gel (Opalescence 15%, Ultradent, USA) by a soft tray for 8 hours per day for two weeks in a dark environment, with a temperature of 37°C. Between each bleaching trial the samples rinsed and remained stored in distilled water.

After bleaching, samples were washed with distilled water and dried with blotting paper and were weighed 3 times like the control groups, abraded by simulated tooth brushing machine and then samples were dried by blotting with a paper and the weigh was recorded as the final one.

The weight loss of the each sample before and after being placed in toothbrush simulator machine was considered as a scale for abrasion of composite. The acquired data were analyzed statistically with one-way ANOVA and Duncan tests.

RESULTS

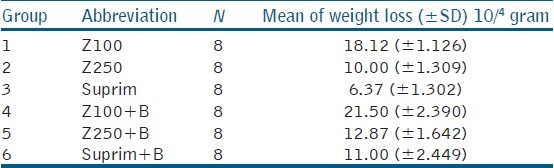

Data for all the experimental groups have been shown in Table 2. According to these data, the maximum abrasion happened in group 4 (Z100 + B) and the least in group 3 (Suprim).

Table 2.

The descriptive data of experimental groups

There was no in reaction between composite type and bleaching variables according to ANOVA and these variables didn’t affect each other mutually (P > 0.05). So the effect of each factor was studied separately. There was a statistical difference between groups (Z100, Z250, Suprim). (P = 0.00) which means the type of composite had a significant effect on abrasion.

On the other hand there was a statistically difference between the bleached groups and non-bleached groups (P = 0.00). This means that bleaching also had a great effect on abrasion.

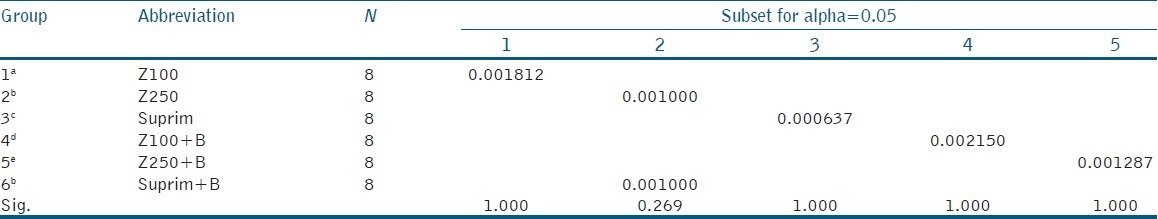

Duncan test was used for comparison among the groups [Table 3]. According to this test, it was observed that there was a significant difference among the groups except group 2 (Z250) and group 6 (Suprim + B).

Table 3.

Duncan test for comparison among the groups

The results showed that the use of bleaching material effectively increased the abrasion of resin composites. This effect was observed in composites with different fillers.

DISCUSSION

The effects of bleaching treatments on enamel have been studied before. Many unfavorable side effects have been reported such as the reduction of micro-hardness,[8] increase in enamel micro porosities, enamel surface erosion and enamel attrition in the long term.[12] One report also points out, even after 6 hours if the teeth are in contact with different types of bleaching, they will be ready for abrasion against brushing.[13]

There are several studies on the effects of bleaching procedure on restorative materials. Bleaching factors affecting the results of the study include: pH, the concentration of the acid, temperature, time of the exposure and number of times the materials have been used.[14]

Because of the extensive range of bleaching pH (3.67-11.13), it is expected that bleaching material with more acidity might cause more reduction in micro hardness of restorative materials.[13]

The effects of low concentration of carbamide peroxide on surface micro hardness of dental composites have been controversial. In some studies softening of the composites after home bleaching has been mentioned.[9,15] Hanning et al. found that the reduction of the hardness happened not only in surface layers but also in deep layers of composite resins[11] while other studies didn’t show changes in hardness after home bleaching gels application[16] and even some studies showed the increase of superficial hardness.[17]

It seems that the reduction of hardness and composite resins softening are the outcomes of free radicals which are created as the result of carbamide peroxide breakdown and has caused a crack in the chain of polymer.[16]

On the other hand it has been specified that in low concentration of carbamide peroxide, the release of low amount of free radicals causes the increase of surface polymerization and lead to increase of surface hardness.[17] It seems that the low concentration of carbamide peroxide causes increase of surface hardness but if the amount of hydrogen peroxide exceeds certain level, the same free radicals will cause the analysis of molecular joining and reduction of the surface hardness.

There are other reasons that justify varied acquired data in different studies such as differences in experimental methodologies, the bleaching agents applied and restorative materials used.[18] The repetition of bleaching agent application causes different results in different studies too.

Recently, Freire et al. claimed that the refrigerated home bleaching gels showed higher pH. They concluded that the bleaching agents’ storage temperature affects their pH.[19]

Dogan showed that the use of home bleaching agents causes more changes in hardness and roughness, compared to office bleaching.[20] This study also justified the result by longer contact time between home bleach materials and the surface of resin composite.

Another factor which has been studied in recent researches is the parameter of solubility. It has been said that if bleaching products had solubility similar to those of resin matrix, chemical softening of restorative materials could occurred. BISGMA and UDMA resin monomers might be soften by chemicals with solubility parameters in the range of 1.82 × 10-4 to 2.97 × 10-4J/m3.[21]

Findings of our study confirm the results of Atali and Topbasi study.[22] They evaluated the effect of three bleaching products on hardness and surface roughness of four types of composites (Hybrid, Nanohybrid, Nanosuperfilled, Silorane base). In this study nanohaybrid composites also showed the least reduction of hardness and surface roughness.

In another study by Mujdeci and Gokay,[23] it was shown that the bleaching agent has an unfavorable effect on micro hardness of Grandio (Nanohybrid resin composite). These findings correspond with our knowledge of abrasion. The existence of small particles in nano composite and the effect of micro protection can also be an explanation for the results.

According to the findings of our study, the nanofilled composite has been the most resistant to abrasion. Of course, it must be noticed that we can’t reach the final conclusion with a test on only one type of composite and repetition of the test with other kinds of composites is required for that. We can offer a stronger remark only after obtaining more similar findings. Furthermore, we should point out that in vitro studies have some limitations to show clinical conditions. These studies have shown that the concentration of peroxide reduces during oral application.[18] While in this study the bleaching agents had not been thinned or buffered during bleaching process.

It has been mentioned that in the presence of saliva a protective layer is formed on the surface of restorative materials and this could change the effects of bleaching materials.[24] In some studies it has been noticed that the materials existing in saliva may act as an accelerator in carbamide peroxide. According to these findings we cannot ignore the effect of saliva on bleaching agent. So it is recommended that next studies be designed in ways that simulate in vivo conditions.

Meanwhile, it should be kept in mind that keeping samples in water, itself causes some changes in the interface between filler and matrix which can be effective in the results of this study.[25]

Therefore, considering all the limitations within this study we can say if bleaching treatment is necessary after restoration treatment preferably, we had better choose nanofilled composite as our first priority.

Destructive effects of bleaching materials on the abrasion of composites in the mouth may come to its lowest level by polishing after the bleaching. So the damaged composite surface may be eliminated and replaced by a suitable surface. The efficiency of this suggestion must be confirmed through controlled studies.

CONCLUSION

According to the result of this study bleaching caused increase of abrasion in all kinds of used composites. Among the composites studied (Z100, Z250, Suprim) there was a significant difference in abrasion. The most amount of abrasion was observed in Z100 (Microhybrid composite). The least amount of abrasion noticed in Suprim (Nanofilled composite).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the Research Council of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was supported by the Research Council of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenwall L. Bleaching techniques in restorative dentistry. London, United kingdom: Martin Dunitz Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haywood VB, Heymann HO. Night guard vital bleaching. Quintessence Int. 1989;20:173–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haywood VB, Heymann HO. Night guard vital bleaching: How safe is it? Quintessence Int. 1991;22:515–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haywood VB. History, safety, and effectiveness of current bleaching techniques and applications of the night guard vital bleaching technique. Quintessence Int. 1992;23:471–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurgan S, Yalcin F. The effect of 2 different bleaching regimens on the surface roughness and hardness of tooth-colored restorative materials. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:e83–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegedus C, Bistey T, Flora-Nagy E, Keszthelyi G, Jenei A. An atomic force microscopy study on the effect of bleaching agents on enamel surface. J Dent. 1999;27:509–15. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moraes RR, Marimon JL, Schneider LF, Correr Sobrinho L, Camacho GB, Bueno M. Carbamide peroxide bleaching agents: Effects on surface roughness of enamel, composite and porcelain. Clin Oral Investig. 2006;10:23–8. doi: 10.1007/s00784-005-0016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basting RT, Rodrigues Junior AL, Serra MC. The effect of 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching material on micro hardness of sound and demineralized enamel and dentin in situ. Oper Dent. 2001;26:531–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swift EJ., Jr Restorative considerations with vital tooth bleaching. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128(Suppl):60S–4S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey SJ, Swift EJ., Jr Effects of home bleaching products on composite resins. Quintessence Int. 1992;23:489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannig C, Duong S, Becker K, Brunner E, Kahler E, Attin T. Effect of bleaching on subsurface micro-hardness of composite and a polyacid modified composite. Dent Mater. 2007;23:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Murr J, Ruel D, St-Georges AJ. Effects of external bleaching on restorative materials: A review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shannon H, Spencer P, Gross K, Tira D. Characterization of enamel exposed to 10% carbamide peroxide bleaching agents. Quintessence Int. 1993;24:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price RB, Sedarous M, Hiltz GS. The pH of tooth-whitening products. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:421–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malkondu Ö, Yurdagüven H, Say EC, Kazazoğlu E, Soyman M. Effect of bleaching on micro hardness of esthetic restorative materials. Oper Dent. 2011;36:177–86. doi: 10.2341/10-078-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Godoy F, Garcia-Godoy A. Effect of bleaching gels on the surface roughness, hardness, and micromorphology of composites. Gen Dent. 2002;50:247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campos I, Briso AL, Pimenta LA, Ambrosano G. Effects of bleaching with carbamide peroxide gels on micro hardness of restoration materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2003;15:175–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2003.tb00187.x. discussion 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCracken MS, Haywood VB. Demineralization effects of 10 percent carbamide peroxide. J Dent. 1996;24:395–8. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(95)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freire A, Archegas LR, de Souza EM, Vieira S. Effect of storage temperature on pH of in-office and at-home dental bleaching agents. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2009;22:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dogan A, Ozcelik S, Dogan OM, Hubbezoglu I, Cakmak M, Bolayir G. Effect of bleaching on roughness of dental composite resins. J Adhes. 2008;84:897–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu W, Toth EE, Moffa JF, Elison JA. Subsurface damage layer of in vivo worn dental composites restorations. J Dent Res. 1984;63:675–80. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630051401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atali PY, Topbasi FB. The effect of different bleaching methods on the surface roughness and hardness of resin composites. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2011;3:10–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mujdeci A, Gokay O. Effect of bleaching agents on the microhardness of tooth-colored restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95:286–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima DA, De Alexandre RS, Martins AC, Aguiar FH, Ambrosano GM, Lovadino JR. Effect of curing lights and bleaching agents on physical properties of a hybrid composite resin. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2008;20:266–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2008.00190.x. discussion 274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakki A, Cilli R, Mondelli RF, Kalachandra S, Pereira JC. Influence of pH environment on polymer based dental material properties. J Dent. 2005;33:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]