Abstract

Aim:

To compare the antimicrobial efficacy of calcium hydroxide (CH), 2% chlorhexidine gel (CHX) and a combination of both, on obligate anaerobes, facultative anaerobes and Candida spp .

Materials and Methods:

90 single rooted permanent teeth were included in the study. After complete disinfection and access opening, the first microbiological pre-treatment sample (S1) was collected. After completion of instrumentation, a post-instumentation sample (S2) was taken and the teeth were divided into three groups: Group I: CH, Group II: 2% CHX, Group III: 2% CHX with CH. After 1 week, a post-medication sample (S3) was collected.

Results:

All three medicaments were effective in the elimination of obligate anaerobes. CHX and combination showed higher antimicrobial effect against facultative anaerobes and Candida spp. in comparison with CH. But there was no statistical significant difference between Group II and Group III.

Conclusion:

CHX with or without CH was more effective than CH alone against all the tested micro-organisms.

Keywords: Calcium hydroxide, chlorhexidine gel, facultative anaerobes, intracanal medicament, obligate anaerobes

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria and their products play a primary etiological role in the initiation and perpetuation of pulpo-periapicalpathosis.[1] Regardless of the files used, technique of instrumentation, type of irrigant used, antisepsis obtained from biomechanical preparation is temporary and partial.[2] Approximately 50% of the teeth still harbor bacteria even after thorough shaping and cleaning.[3]

Application of calcium hydroxide (CH) for a week has been shown to be reduce the microorganisms to negligible.[4] Chlorhexidine (CHX) has been shown to be more effective in eliminating CH-resistant microorganisms like E. faecalis inside dentinal tubules.[5] It has been demonstrated to attain 78% negative cultures after a 7 day application.[6] But it does not act as a physical barrier against microbial recolonization and has no detoxifying ability against endotoxins.[7]

Despite conflicting claims, no medicament appears to be ideal and significant variability exists in clinical dental practice regarding their use. So, a combination of the two medicaments has been used to check for a possible additive or synergistic effect.[8–11] Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess antibacterial effect of the three different intracanal medicaments against various microorganisms in in-vivo conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study cohort

79 patients with 90 single rooted teeth of the age range 15-50 years were selected for the study. Prior clearance of the protocol from the University Ethical Committee and informed consent from each patient were taken.

Criteria for inclusion/exclusion

Patients with non-contributory medical history, intact permanent teeth without any previous restoration, with a necrotic or infected pulp as diagnosed clinically and radiographically, with adequate coronal structure for proper isolation, temporization, and restoration were included in the study.

Patients with systemic conditions, acute periapical abscess, retreatment cases, patients on antibiotic therapy within 3 months, teeth with calcified canals, sinus opening, immature apex, internal or external resorption or periodontal pockets >5 mm and pregnant women were excluded.

Preparation of 2% CHX gel

CHX gel was prepared with 20% Chlorhexidinedigluconate solution (Sigma Aldrich, Bangalore) in a gel base of 1% Natrasol (Hydroxyethyl cellulose) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 20% Barium sulfate (Rolex Chemical Industries, Mumbai).[9]

First treatment session

Each tooth was anaesthetized and isolated with rubber dam followed by gross caries removal. It was then disinfected with 30% hydrogen peroxide and 5% iodine tincture for 60 seconds each and neutralized with 5% sodium thiosulfate.[12]

To ensure thorough disinfection, a disinfection sample (S0) was taken by flooding the tooth with thioglycollate broth (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt Limited, Mumbai) and absorbing the contents with paper points. Pulp chamber was opened and working length was estimated by an apex locator (Root ZX- J Morita MFG., Japan).

Pre-treatment sample (S1) was obtained by injecting thioglycollate broth into the root canal and circumferentially pumping a #10/15K- file (Mani Inc, Japan) 1 mm short of the working length. Working length was then confirmed with an intraraoralperiapical radiograph (IOPAR). A sterile paper point (Dentsply, Maillifer) was inserted for 60 seconds and immediately transferred to the transport media- thioglycollate broth with haemin and vitamin K. Three paper points were taken for each sample.

Canals were enlarged with rotary NiTi files-Protaper universal (Dentsply, Maillefer) with EDTA-RC prep (Premier Dental Products, Norrstown, PA) as a lubricant. After obtaining clearance from the university ethical committee, saline was used for irrigation with side-vented irrigation needles. Saline was used for irrigation to prevent bias caused by the activity of the irrigant itself. This was followed by collection of post-instrumentation sample (S2) in the same manner as (S1).

Samples were placed in a microtube containing 1.4 ml of transport media and transferred to laboratory for processing within 2 hours. After the second sampling, root canals were divided into three groups (n = 30) randomly:

Group I: Calcium hydroxide paste (RC Cal, Prime Dental, Mumbai)

Group II: 2% Chlorhexidinegluconate gel

Group III: 2% Chlorhexidinegluconate gel with calcium hydroxide (1:1)

Canals were dried with paper points followed by the application of medicaments. The extent and compactness of the fill was confirmed with an IOPAR. A double seal of Cavit-G (3M ESPE, United States) and glass ionomer cement (Ketac-Fil, 3M ESPE) was placed for 7 days.

Second treatment session

After prior anaesthesia, isolation, and disinfection, root canals were reinstrumented passively with H-files (Mani Inc, Japan) and irrigated with saline to remove the medicaments. 2 ml of 3% Tween 80 and 0.3% L α-lecithin each were used to neutralize the CHX, 2 ml 0.5% citric acid was used to neutralize CH, both of them were used to neutralize the combination over a period of 5 minutes.[8] This was followed by irrigation with 5 ml of sterile saline and collection of post-medication sample (S3) similar to the collection of (S1). Teeth were obturated by lateral condensation technique with AH Plus sealer (DentsplyDeTrey, Germany) and restored.

Microbiological procedure

Microbiological samples were pre-incubated for 30 minutes and shaken vigorously in a vortex mixture for 60 seconds. They were subjected to serial ten-fold dilution up to 1:104 in brain heart infusion broth under anaerobic conditions. 50 μl of undiluted sample and each of the three dilutions were inoculated in the culture media with 5.0 μg/ml haemin and 0.5 μg/ml menadione.

For obligate anaerobes supplemented blood agar, Bacteroides bile esculin agar (HiMedia) and Brewer anaerobic agar (HiMedia) were used for culture. The plates were incubated anaerobically in sealed jars with a gas mixture (10% H2, 10% CO2, and 80% N2). Separate selective media Actinomyces agar (HiMedia) and Sabouraud's Dextrose agar (HiMedia) with 100 μg/ml chloramphenicol were prepared for Actinomyces and Candida spp., respectively.

For facultative anaerobes, the same dilutions were inoculated on 5% sheep blood brain heart infusion agar, MacConkey's agar (HiMedia), and MitisSalivarious agar (MSA) (HiMedia). The first two media were incubated aerobically for 24-48 hours and MSA (5% CO2) for 48 hours.

All plates were counted for Colony Forming Units/ml (CFU/ml) after 7 and 14 days. The organisms were identified using gram-staining, catalase production, colony morphology on blood agar, and using biochemical identification kit- API (BioMerieux SA, France).

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed by SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA) software using the analysis of variance (ANOVA), Students paired “t” test and Tukey's (P < 0.05) test and Shaperio-Wilk W test. Since there are three groups, the ANOVA was used to find the significance, the multiple comparison test or pair wise comparison was done using the TUKEY post hoc test and Students paired “t” test was used for a comparison of mean between two samples of three groups.

RESULTS

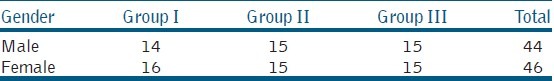

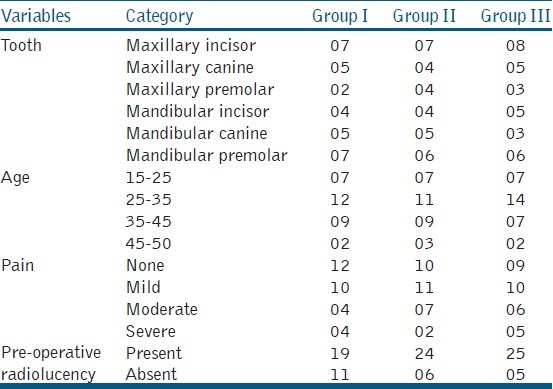

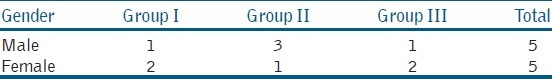

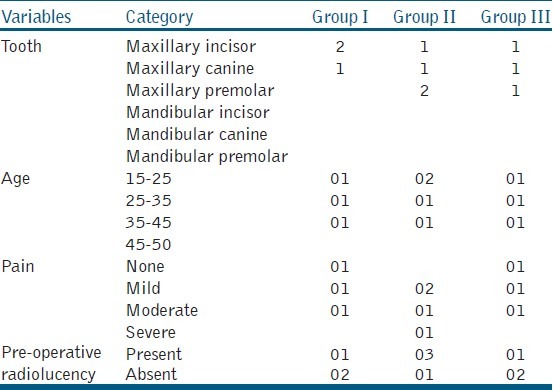

Data was normally distributed as tested using the Shaperio-Wilk W test. Tables 1 and 2 show gender-wise distribution and base line comparison (tooth, age, pain, and pre-operative radiolucency) of the groups involved in the study. Patient compliance was checked as follows, after 1 week when the patient reported for the second treatment session, the double seal was checked if the restoration was intact without any fracture. In none of the cases fracture could be detected. In the present study, 6 (S0) samples showed contamination and there were 4 drop-out cases which were excluded, so statistical analysis was carried out of 80 teeth. 6 (S-0) samples were excluded due to contamination (2 from Gp-I, 3 from Gp-II, and 1 from Gp-III) and 4 cases dropped out (1 from Gp-I, 1 from Gp-II, and 2 from Gp-III). Individual root canal yielded 3–9 bacterial species of which 64% were obligate anaerobes and 34% were Gram negative.

Table 1.

Gender-wise distribution

Table 2.

Base line comparison of the groups involved in the study

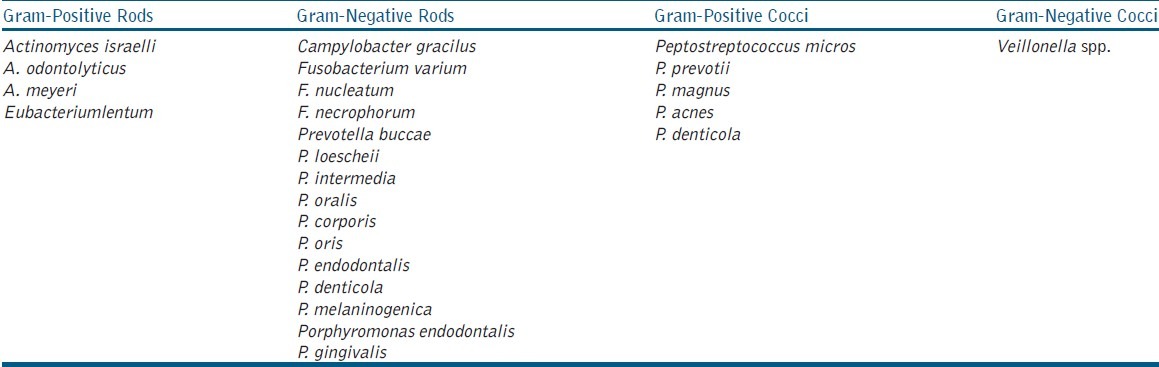

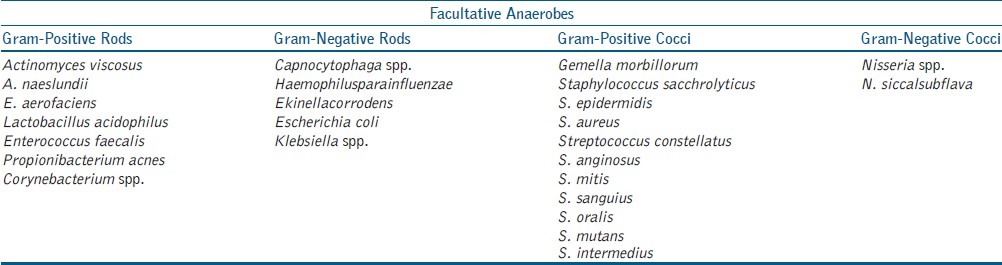

Bacterial genera isolated included Peptostreptococcus 48 (60%), Enterococcus 17 (21.25%), Staphylococcus 10 (12.5%), Streptococcus 47 (58.75%), Corynebacterium 4 (5%), Veillonella 8 (10%), Lactobacillus 8 (10%), Klebsiella 4 (5%), Fusobacterium 52 (65%), Porphyromonas 64 (80%), Prevotella 52 (75%), Actinomyces 7 (8.75%), Candida 16 (20%), Eubacterium 6 (7.5%) and Compylobacter 9 (11.2%). C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. crusei were the species isolated from Candida genera. The species identified have been tabulated in Table 3, Table 4 based on oxygen requirement, morphology, and Gram staining.

Table 3.

Obligate anaerobes isolated from 80 necrotic root canals

Table 4.

Facultative anaerobes isolated from 80 necrotic root canals

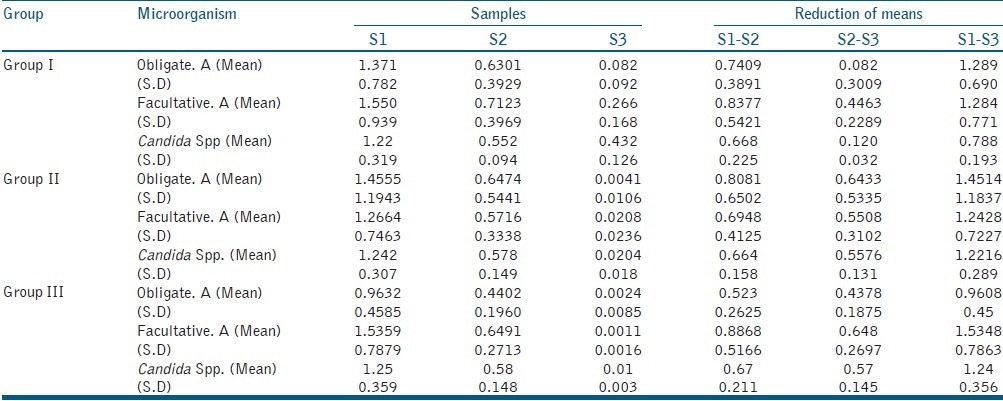

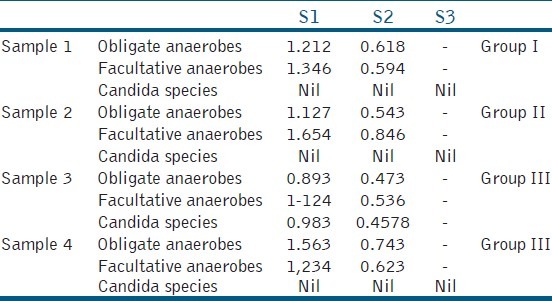

Total count of the microorganisms was expressed in CFU/ml after a log10 transformation to normalize the data. A comparison between the CFU/ml showed a clinically significant percentage reduction from S1 to S2 and S1 to S3 in all groups. Biomechanical preparation reduced the initial microbial load significantly [Table 5].

Table 5.

Bacterial count (CFU/ml × 105) at - S1, S2, S3 stages and reduction in mean of Group I, Group II and Group III of obligate anaerobes (Obligate. A), facultative anaerobes (Facultative. A) and Candida Spp. (Standard deviation‑SD)

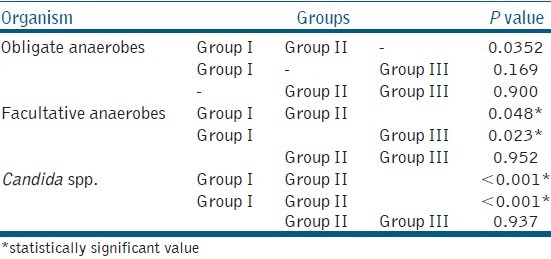

Students paired “t” test was used to check microbial reduction between S1, S2, and S3 samples. Comparing CFU/ml of facultative anaerobes and Candida spp. in the groups, ANOVA showed non-homogeneity among groups. “Tukeys” test [Table 6] showed a significant difference (P < 0.05) between Group I with Group II and Group III but not (P > 0.05) between Group II and Group III.

Table 6.

Multiple Comparisons of obligate anaerobes, facultative anaerobes and Candida spp. among the three groups using Tukeys Test. (*statistically significant value)

Comparing the groups of obligate anaerobes, the ANOVA test showed homogeneity among all the groups. Tukeys’ test [Table 6] showed a non-significant (P > 0.05) difference between the groups.

Drop out analysis

Drop out cases were statistically similar with respect to age in all three groups (P = 1.000). Gender of drop out cases was statistically similar in three groups studied (P = 1.000) [Table 7]. Pain distribution was not statistically significant in three groups (P = 0.931). Pre-operative radiolucency on drop out cases was statistically similar in three groups (P= 0.57). Overall, the baseline characteristics of drop out cases were not changed significantly, hence the characteristics of design is unchanged due to dropout as per the drop out analysis. Therefore, the results presented excluding drop did not produce any bias on outcome variable [Tables 8 and 9].

Table 7.

Gender details of the 10 drop out cases

Table 8.

Details of the 10 drop out cases

Table 9.

Details of the 4 drop out cases of the 10 excluded cases. The 6S(0) Samples which showed contamination were not subjected to further microbiological testing so they are not present in the table

DISCUSSION

Primary endodontic infections are dominated by obligate anaerobes, whereas facultative anaerobes and Candida spp. are frequently encountered in secondary endodontic infections. This could have been the reason for the low isolation rate of Candida spp. (19%) and E. faecalis (21%) in the present study. So the conclusions drawn about Candida have to be evaluated with caution.

In the inclusion criteria to reduce the variation in results only asymptomatic teeth were included, teeth with acute clinical signs or with sinus tracts were excluded, as they have greater bacterial concentration. Additionally, the periapical exudate seeping into the root canal between treatment sessions can result in increased bacterial counts at the second session.[13] Teeth with coronal restoration were also excluded because the bacteria at the restoration margins can cause contamination during the medication period.[12]

A negative control group with no medication was not included due to ethical concerns. Medicaments were applied for 7 days so that their complete antimicrobial effect could be obtained as reported in previous studies.[4,14]

The presence of false-positive and negative cultures makes the results obtained from bacterial cultures questionable.[15] False-positive results can occur because of salivary leakage, contamination during sampling, clinical/laboratory handling. To avoid this sterility check sample (S0) were taken. False-negative results can occur due to carry-over effect of the medicaments used during therapy, so they were inactivated before acquiring the post-medication samples by suitable agents.[15]

Percentage reduction with CH was 95% and 82% for obligate and facultative anaerobes respectively and 61% for Candida spp. Its higher antimicrobial activity against obligate anaerobes has been reported previously in many studies[4,13] which have attributed it to the lethal effects of hydroxyl ions on bacterial cells that disrupts the established nutritional relationships. Its lower efficacy against facultative anaerobes has also been shown previously.[16,17] Gomes et al.[9] found facultative anaerobes like E. faecalis showed the smallest inhibition zone against CH while strict anaerobes showed the largest. De Souza et al.[18] have also reported a reduction of most species initially detected but found a modest increase in some species like A. actinomycetemcomitans after medication with CH. Similarly Waltimo et al.[17] found that Candida spp. showed either equally high or higher resistance to CH than E. faecalis.

In accordance with previous studies,[19,20] CHX alone showed strong antimicrobial activity and reduced the obligate anaerobes, facultative anaerobes and Candida spp. to 95%, 97%, and 8% respectively in this study. This has been explained by its mechanism of action, as it increases membrane permeability leading to leakage of low molecular weight ions like potassium ions and phosphorus ions at low concentration and precipitation of cytoplasmic contents at a higher concentration. In an in vivo study[8] involving primary teeth, CHX, both with and without CH, was found to be more effective against E. faecalis than CH alone. Similarly, Ercan et al. found a higher reduction with C. albicans after a 7 day application.[21]

As reported in earlier studies[10,22] combination medicament was found to be equally effective against all tested microorganisms showing a reduction in the range of 98-99% and maximum number of negative cultures in the S3 samples. Although no additional advantage of the combination statistically could be found but neither a decrease in the antimicrobial efficacy was seen as previously reported.[23] Nevertheless, many studies have demonstrated that CHX gel alone has a greater antimicrobial effect than the combination.[5,23] These differences might be due to the vast variation between the in vivo and in vitro conditions as most of these studies were in vitro conditions.

For any intracanal medicament to exert its full biological effect, placement both in sufficient quantity and close proximity of apical region to allow its diffusion into critical areas is of prime importance.[24] The higher reduction found in this study could be possibly because of better compaction of the medicaments due to their radiopacity which allowed evaluation of both the above-mentioned criteria.

Previous in vivo studies on intracanal medicaments have either concentrated on a specific microorganism[8] or have taken total count of bacteria into consideration.[25] The relevance of this randomized clinical trial study can be related to the in vivo condition where it was carried out, which allowed multifactorial events like symbiosis and antagonism among bacteria that determine the efficacy of medicaments to be evaluated.

Limitations of the present study are that, it did not conform to the CONSORT guidelines, which would have helped in making the groups more comparable and minimize the chances of bias as well as limit confounders. A randomized control trial was not possible in this study design because for a true randomization, a sampling frame (a complete list of eligible subjects) was needed. In this study, the authors followed “alternate group allocation,” which means that each subject recruited in the study had equal chances of being selected in any of the groups. Thus, this eliminated the bias.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitation of this study, CH showed limited efficacy against facultative anaerobes and Candida spp. but was effective against obligate anaerobes, whereas CHX and combination were effective against all tested microorganisms. Further research is warranted using better qualitative and quantitative isolation methods of microorganisms and alternate intracanal medicaments should be tested against individual root canal microorganism.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gomes BP, Ferraz CC, Garrido FD, Rosalen PL, Zaia AA, Teixeira FB, et al. Microbial susceptibility to calcium hydroxide pastes and their vehicles. J Endod. 2002;28:758–61. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soares JA, Leonardo MR, da Silva LA, Tanomaru Filho M, Ito IY. Elimination of intracanal infection in dog's teeth with induced periapical lesions after rotary instrumentation: Influence of different calcium hydroxide pastes. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006;14:172–7. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572006000300005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bystrom A, Sundqvist G. Bacteriologic evaluation of the efficacy of mechanical root canal instrumentation in endodontic therapy. Scand J Dent Res. 1981;89:321–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1981.tb01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjogren U, Figdor D, Spangberg L, Sundqvist G. The antimicrobial effect of calcium hydroxide as a short-term intracanal dressing. Int Endod J. 1991;24:119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1991.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siren EK, Haapasalo MP, Waltimo TM, Orstavik D. In vitro antibacterial effect of calcium hydroxide combined with chlorhexidine or iodine potassium iodide on Enterococcus faecalis. Eur J Oral Sci. 2004;112:326–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbosa CA, Goncalves RB, Siqueira JF, Jr, De Uzeda M. Evaluation of the antibacterial activities of calcium hydroxide, chlorhexidine, and camphorated paramonochlorophenol as intracanal medicament. A clinical and laboratory study. J Endod. 1997;23:297–300. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buck RA, Cai J, Eleazer PD, Staat RH, Hurst HE. Detoxification of endotoxin by endodontic irrigants and calcium hydroxide. J Endod. 2001;27:325–7. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oncag O, Cogulu D, Uzel A. Efficacy of various intracanal medicaments against Enterococcus Faecalis in primary teeth: An in vivo study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;30:233–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomes BP, Vianna ME, Sena NT, Zaia AA, Ferraz CC, de Souza Filho FJ. In vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of calcium hydroxide combined with chlorhexidine gel used as intracanal medicament. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Endod. 2006;102:544–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podbielski A, Spahr A, Haller B. Additive antimicrobial activity of calcium hydroxide and chlorhexidine on common endodontic bacterial pathogens. J Endod. 2003;29:340–5. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zerella JA, Fouad AF, Spangberg LS. Effectiveness of a calcium hydroxide and chlorhexidinedigluconate mixture as disinfectant during retreatment of failed endodontic cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:756–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moller AJ. Microbiological examination of root canals and periapical tissues of human teeth: Methodological studies. Odontol Tidskr. 1966;74:1–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orstavik D, Kerekes K, Molven O. Effects of extensive apical reaming and calcium hydroxide dressing on bacterial infection during treatment of apical periodontitis: A pilot study. Int Endod J. 1991;24:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1991.tb00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenet BJ, Komorowski R, Wu XY, Huang J, Grad H, Lawrence HP, et al. Antimicrobial substantivity of bovine root dentin exposed to different chlorhexidine delivery vehicles. J Endod. 2000;26:652–5. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamany A, Spangberg LS. An effective method of inactivating chlorhexidine. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:617–20. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.122346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans M, Davies JK, Sundqvist G, Figdor D. Mechanism involved in the resistance of E.Faecalis to calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J. 2002;35:221–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waltimo TM, Orstavik D, Sirén EK, Haapasalo MP. In vitro susceptibility of Candida albicans to four disinfectants and their combinations. Int Endod J. 1999;32:421–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Souza CA, Teles RP, Souto R, Chaves MA, Colombo AP. Endodontic therapy associated with calcium hydroxide as an intracanal dressing: Microbiologic evaluation by the checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization technique. J Endod. 2005;31:79–83. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000133157.60731.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rocas IN, Lopes HP, Magalhaes FA, de Uzeda M. Elimination of Candida albicans infection of the radicular dentin by Intracanal Medications. J Endod. 2003;29:501–4. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Souza-Filho FJ, Soares AJ, Vianna ME, Zaia AA, Ferraz CC, Gomes BP. Antimicrobial effect and pH of chlorhexidine gel and calcium hydroxide alone and associated with other materials. Braz Dent J. 2008;19:28–33. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402008000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ercan E, Dalli M, Dülgergil CT. In vitro assessment of the effectiveness of chlorhexidine gel and calcium hydroxide paste with chlorhexidine against Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:e27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basrani B, Tjaderhane L, Santos JM, Pascon E, Grad H, Lawrence HP, et al. Efficacy of chlorhexidine- and calcium hydroxide–containing medicaments against Enterococcus faecalis in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:618–24. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haenni S, Schmidlin PR, Mueller B, Sener B, Zehnder M. Chemical and antimicrobial properties of calcium hydroxide mixed with irrigating solutions. Int Endod J. 2003;36:100–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomes BP, Ferraz CC, Vianna ME, Rosalen PL, Zaia AA, Teixeira FB, et al. In vitro Antimicrobial activity of calcium hydroxide pastes and their vehicles against selected microorganisms. Braz Dent J. 2002;13:155–61. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402002000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paquette L, Legner M, Fillery ED, Friedman S. Antibacterial efficacy of chlorhexidinegluconateintracanal medication in vivo. J Endod. 2007;33:788–95. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]