Abstract

Mandibular premolars have earned the reputation for having aberrant anatomy. The literature is replete with reports of extra canals in mandibular first premolars, but reports about the incidence of extra roots in these teeth are quite rare. This paper attempts at explaining a rare case of successful endodontic management of a four-rooted mandibular first premolar with diagnostic, interoperative and postoperative radiographic records along with a substantial data on the incidence of extra roots in these teeth. The standard method of radiographic appraisal was maintained as the criteria for determining the presence of extra roots.

Keywords: Anomalies, diagnosis, mandibular first premolar, root canal morphology

INTRODUCTION

A thorough understanding of root canal anatomy and morphology is required for achieving high levels of success in endodontic treatment. Failure to recognize variations in root or root canal anatomy can result in the unsuccessful endodontic treatment. Hence, it is imperative that the clinician be well informed and alerted to the commonest possible variations. Hoen and Pink in their analysis on teeth requiring re-treatment, found a 42% incidence of missed roots or canals.[1]

Mandibular premolars have earned the reputation for having the most aberrant anatomy. Numerous reports of root canal variations in these teeth have been reported in the literature.[2,3] Vertucci in his series of studies conducted on extracted teeth, reported 2.5% incidence of a second canal.[4] Zilich and Dawson reported 11.7% occurrence of two canals and 0.4% of three canals.[5] In the case of mandibular first premolars, it is normally a single-rooted tooth. The frequency of occurrence of two roots is 1.8% while three roots are reported to be present in 0.2%of cases. In single-rooted mandibular first premolars, two or more canals are found in 23.2% of cases.[6] These anatomic abnormalities are additional challenges, which begin at the case assessment and involve all operative stages, including access cavity design, localization, cleaning, and shaping of the root canal system. Although preoperative radiography gives a two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional object, precise interpretation can reveal external and anatomic details that suggest the presence of extra canals or roots.

The purpose of this clinical report is to describe an anatomic abnormality that was detected during routine root canal treatment in a mandibular first premolar.

CASE REPORT

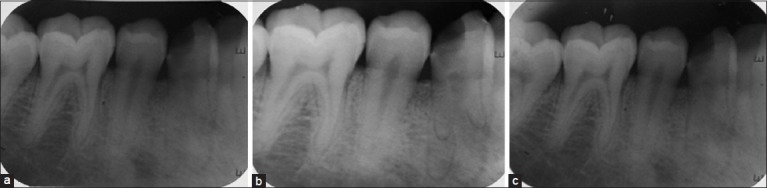

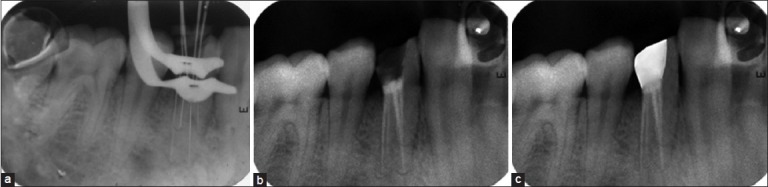

A 24-year-old male patient came to a private dental clinic with pain in the left lower back tooth. On intraoral clinical examination, there was a decayed 34. An intraoral periapical radiograph was advised. On radiographic examination preoperative radiograph revealed radiolucency involving pulp with respect to 34 [Figure 1a]. Diagnosis of acute irreversible pulpitis was made. Also IOPA revealed 34 having four roots. To confirm the presence of four roots two more radiographs one with distal angulation and the other with mesial angulation were taken [Figure 1b, and c]. Access was gained to the pulp chamber after administration of local anesthesia (2% Lignocaine with 1:100000 epinephrine), under rubber dam isolation. To gain sufficient access to the canals, the conventional access opening was modified into one that was wider. Orifice location was not easy as the coronal pulp chamber was unusually long. After careful inspection, four canal orifices were located and patency was ascertained using a small size K-file (Kerr, Orange, California). Mesiobuccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual, and distolingual canals were identified. Working length was established with the use of apex locator (Root ZX, J. Morita Inc.) Then the working length radiograph was taken and measured Figure 2a].

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative intraoral periapical radiograph (straight angulation) (b) Preoperative intraoral periapical radiograph (mesial angulation) (c) Preoperative intraoral periapical radiograph (distal angulation)

Figure 2.

(a) Working length radiograph (b) Postobturation radiograph (c) Recall radiograph 1-year postoperatively

The canals were cleaned and shaped with hand K-files and nickel titanium rotary ProTaper files (Dentsply Maillefer, Switzerland). The canals were sequentially irrigated using 5.25% Sodium hypochlorite and 17% EDTA during the cleaning and shaping procedure. The canals were thoroughly dried and obturation was done using F2 Pro Taper Gutta-percha and AH Plus sealer (Dentsply, Maillefer, Switzerland).

The post-endodontic permanent restoration was completed with composite (3M ESPE Dental Products, St Paul, MN) [Figure 2b]. The patient was reviewed after a month and was found to be asymptomatic. A 1-year recall radiograph showed satisfactory healing and was advised to get this tooth crowned [Figure 2c].

DISCUSSION

The presence of extra roots or canals in mandibular premolars is undoubtedly an endodontic challenge. Clearly, these findings are clinically important as in a study at the University of Washington assessing the results of endodontic therapy, the mandibular first and second premolars showed failure rates of 11.45% and 4.54%, respectively.[7] Conceivably, these findings could be due to the complex root canal anatomy of a large number of these teeth. A wide range of opinions are reported in the literature regarding the number of root canals, but there are very few reports on the variations in the numbers of roots that occur in mandibular premolars.[8,9] Accurate preoperative radiographs, straight and angled, using parallel technique are essential in providing clues as to the number of roots that exist.[10] Optimum opening of the access cavity is absolutely necessary. Despite the existence of complicated dental anatomy, shaping outcomes with nickel–titanium instruments are mostly predictable.[11] Cautious use of rotary or hand nickel–titanium files prepares the canals to a predetermined shape.

There are many reports regarding four root canals in mandibular second premolar[12–14] and five-canaled mandibular second premolar[15] but four canals in mandibular first premolar is hard to find in the published literature. These discussions also validate an important consideration that must not be overlooked, that is, the anatomic position of the mental foramen and the neurovascular structures that pass through it, in close proximity to the apices of the mandibular first and second premolars. There are reports in the literature, of flare-ups in mandibular first and second premolars with associated paresthesia of the inferior alveolar and mental nerves.[16,17] The failure to recognize the presence of extra root or canals can often lead to acute flare-ups during treatment and subsequent failure of endodontic therapy.

CONCLUSION

Successful and predictable endodontic treatment requires knowledge of biology, physiology, and root canal anatomy. The clinician should be astute enough to identify the presence of unusual numbers of roots and their morphology. Teeth with extra roots and/or canals pose a particular challenge. A thorough knowledge of root canal anatomy and its variations, careful interpretation of the radiograph, close clinical inspection of the floor of the chamber, and proper modification of access opening are essential for a successful treatment outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoen MM, Pink FE. Contemporary endodontic retreatments: An analysis based on clinical treatment findings. J Endod. 2002;28:834–6. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vertucci FJ. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:589–99. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerekes K, Tronstad L. Morphometric observations on root canals of human premolars. J Endod. 1977;3:74–9. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(77)80019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vertucci FJ. Root canal morphology of mandibular premolars. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;97:47–50. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zilich R, Dowson J. Root canal morphology of mandibular first and second premolars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;36:738–44. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(73)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingle JI, Simon JH, Machatou P, Bogaerts P. Textbook of Endodontics. 5th ed. Hamilton Ontario, Canada: BC Deker Inc; 2002. Outcome of endodontic treatment and re-treatment; p. 751. Chapter 13. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingle JI, Simon JH, Machatou P, Bogaerts P. Textbook of Endodontics. 5th ed. Ontario, Canada: BC Deker Inc; 2002. Outcome of endodontic treatment and re-treatment; pp. 748–50. Chapter 13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goswami M, Chandra S, Chandra S, Singh S. Mandibular premolar with two roots. J Endod. 1997;23:187. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shapira Y, Delivanis P. Multiple-rooted mandibular second premolars. J Endod. 1982;8:231–2. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(82)80360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silha RE. Paralleling long cone techic. Dent Radiogr Photogr. 1968;41:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters OA. Current challenges and concepts in the preparation of root canal systems: A review. J Endod. 2004;30:559–67. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000129039.59003.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farmakis ET. Four-rooted mandibular second premolar. Aust Endod J. 2008;34:126–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2007.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holtzman L. Root canal treatment of mandibular second premolar with four root canals: A case report. Int Endod J. 1998;31:364–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1998.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sachdeva GS, Ballal S, Gopikrishna V, Kandaswamy D. Endodontic management of a mandibular second premolar with four roots and four root canals with the aid of spiral computed tomography: A case report. J Endod. 2008;34:104–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macri E, Zmener O. Five canals in a mandibular second premolar. J Endod. 2000;26:304–5. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200005000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glassman GD. Flare-up with associated parasthesia of a mandibularsecond premolar with three root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:110–3. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prakash R, Nandini S, Ballal S, Kumar SN, Kandaswamy D. Two-rooted mandibular second premolars: Case report and survey Indian. J Dent Res. 2008;19:70–3. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.38936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]