Background: Humoral immunity against the protease inhibitor serpin B13 is associated with partial protection from type 1 diabetes.

Results: Anti-serpin B13 antibodies up-regulate the cleavage of CD4 and CD19 molecules in lymphocytes residing in pancreatic islets and lymph nodes.

Conclusion: Antibodies prevent serpin B13 from neutralizing proteases, thereby impairing leukocyte function.

Significance: Enhancement of humoral immunity against serpin B13 should impede the progression of pathologic changes in type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: Antibodies, Autoimmunity, Diabetes, Protease, Serpin

Abstract

Secretion of anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies in young diabetes-prone nonobese diabetic mice is associated with reduced inflammation in pancreatic islets and a slower progression to autoimmune diabetes. Injection of these mice with a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against serpin B13 also leads to fewer inflammatory cells in the islets and more rapid recovery from recent-onset diabetes. The exact mechanism by which anti-serpin activity is protective remains unclear. We found that serpin B13 is expressed in the exocrine component of the mouse pancreas, including the ductal cells. We also found that anti-serpin B13 mAb blocked the inhibitory activity of serpin B13, thereby allowing partial preservation of the function of its target protease. Consistent with the hypothesis that anti-clade B serpin activity blocks the serpin from binding, exposure to exogenous anti-serpin B13 mAb or endogenous anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies resulted in cleavage of the surface molecules CD4 and CD19 in lymphocytes that accumulated in the pancreatic islets and pancreatic lymph nodes but not in the inguinal lymph nodes. This cleavage was inhibited by an E64 protease inhibitor. Consequently, T cells with the truncated form of CD4 secreted reduced levels of interferon-γ. We conclude that anti-serpin antibodies prevent serpin B13 from neutralizing proteases, thereby impairing leukocyte function and reducing the severity of autoimmune inflammation.

Introduction

The balance between proteases and their inhibitors is vital to the survival of multicellular organisms (1). Enhanced protease activity impacts negatively on homeostasis by up-regulating the cleavage of native proteins into short peptides and increasing their presentation to autoreactive T cells (2). Proteases can also influence many other processes, including tissue remodeling and resolution of inflammation (3, 4), suggesting that their activity is not always pathogenic. Given the critical role of protease activity during formation of autoimmune inflammation (2, 5, 6), it is not surprising that proteases are modulated by a number of inhibitors, including B clade molecules, also known as ov-serpins (7, 8). The inhibitory activity of these serpins may in turn be regulated. For example, the cofactor heparin markedly enhances the ability of ov-serpins SCCA-1 and SCCA-2 to neutralize their target protease (9).

Recently, we found that young diabetes-prone nonobese (NOD)2 mice (10, 11) secrete autoantibodies against a member of the clade B family called serpin B13 (12–14) and that this response is associated with protection from early-onset autoimmune diabetes (15). Because autoantibodies that interfere with enzyme cascade activities have been described in several pathologic conditions (16–19), we aimed to address whether anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies actively protect from autoimmune diabetes by regulating the balance between this serpin and its protease targets. Using a monoclonal antibody against serpin B13 as a model, we found that humoral activity against this serpin partially preserves the function of proteases and causes enhanced cleavage of lymphocyte surface molecules. Our data also show that it is likely that natural anti-serpin autoantibodies act in a fashion similar to that described for monoclonal antibody during months preceding the development of autoimmune diabetes. Ultimately, this response may interfere with the normal function of inflammatory cells in the pancreatic tissue and contribute to slower progression of pathologic changes in autoimmune diabetes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

The NOD/LtJ and BDC2.5 T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic NOD mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were used to study the effects of treatment with anti-serpin B13 monoclonal antibody (mAb). The University Committee on Animal Resources at the University of Rochester approved all mouse experiments.

Antibodies

FITC-conjugated mAbs were used against CD19 (clone 1D3) and the Vβ4 TCR chain (clone KT4); phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mAbs were used against B220 (clone RA3-6B2), CD4 (clone RM4-5), TCR (H57-597), and leukocyte common antigen (clone 30-F11) (BD Biosciences); and allophycocyanin-conjugated mAb was used against IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2). A mAb against serpin B13 (clone B29) was produced in our laboratory as described previously (15).

Reagents

Bis(carboxybenzyl-l-phenylalanyl-l-arginine amide))-rhodamine 110 was purchased from Invitrogen. E64, an irreversible, potent, and selective inhibitor of cysteine proteases, was obtained from Sigma. E64-d, a cell permeable inhibitor, was from Enzo Life Sciences. BDC2.5 mimotope (RTRPLWVRME) was synthesized at the Keck Facility of the Yale University School of Medicine. Recombinant mouse CD4 was from Sino Biological Inc. Purified mouse serpin B13 expressed in the baculovirus and Escherichia coli were obtained from GenScript. Purified keratin-19 was from Abcam.

Treatment of NOD/LtJ Mice with Anti-serpin B13 mAb and Protease Inhibitor

Four-week-old female NOD/LtJ mice were injected intravenously four times over a period of 10 days with anti-serpin B13 mAb (100 μg/injection). In addition, during the same period, some animals were also injected intraperitoneally with the protease inhibitor E64 at 10 mg/kg/day for several days (20). Control mice were treated with diluent (a sterilized PBS solution containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide) and control IgG. The solutions containing E64 or dimethyl sulfoxide were prepared immediately before use. Twenty-four hours after the last injection, the mice were killed, and cells from their lymphoid organs and pancreatic islets were subjected to FACS analysis.

Luminex Assay

Luminex-based technology was used to measure the serum-binding activity of serpin B13 exactly as described previously (15).

ELISA

The Quantikine immunoassay (R&D Systems) was used to measure IFN-γ concentration according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Preparation of CD4 T Cells and Antigen-presenting Cells

CD4 T cells were isolated by sorting as described in the legend to Fig. 5. T cell-depleted antigen-presenting cells were prepared by Ab-mediated complement lysis of NOD splenocytes. Briefly, spleen cells were depleted of erythrocytes by centrifugation on a lymphocyte separation medium (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and incubated first with a mixture of anti-Thy1 (Tyr-19), anti-CD8 (TIB-105), and anti-CD4 (GK1.5) mAbs and then with low-toxicity rabbit complement and 50 μg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma). The purity of the antigen-presenting cells was 90–95% as determined by staining with anti-MHC class II mAb.

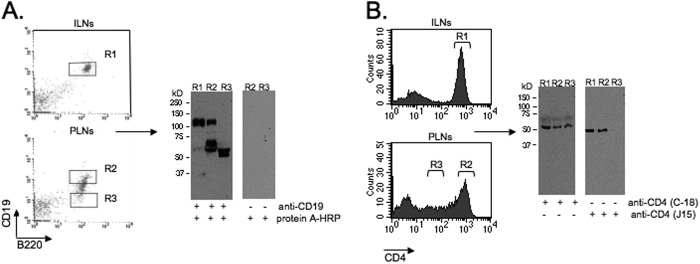

FIGURE 5.

Cleavage of CD4 and CD19 in the PLNs. Shown are the results from Western blot analysis of CD4 and CD19 in cells from inguinal lymph nodes (ILNs) and PLNs, sorted for the high (R1 and R2) and intermediate/low (R3) levels of these markers. The blots were stained with an anti-CD19 antibody that recognizes the cytoplasmic portion of the molecule (A) or two different anti-CD4 antibodies that recognize the intracellular (C-18) or extracellular (J15) portion of CD4 (B). The control blot (A, right panels) was stained with the secondary reagent only. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Immunochemistry

The pancreases were embedded in an optimal cutting temperature medium, instantly frozen in a dry ice/2-methylbutane bath, and then cut into 5-μm sections. To detect glucagon, tissue sections were stained with purified rabbit anti-mouse glucagon IgG (1:50; Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by a secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Invitrogen). To detect CD31, FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD31 mAb (1:100; BD Pharmingen) was used. To detect keratin-19, purified rabbit anti-mouse keratin-19 IgG (1:200; US Biological) was used, followed by a secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200). To detect serpin B13, purified mouse anti-serpin B13 mAb (1:1000; final concentration of 3 μg/ml) was used, followed by a secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Invitrogen). The sections were viewed through n Nikon Eclipse 50i immunofluorescence microscope fitted with a SPOT digital camera using the SPOT advanced program (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc.). The images were captured with a 20 × 0.5 NA or 10 × 0.25 NA objective and processed using Adobe Photoshop (version 7.0).

Western Blots

To verify the expression of His-tagged proteins, including clade B serpins, 293T cell transfectants were lysed in buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and a commercial protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics). Protein samples from precleared cell lysates were fractionated under reducing conditions on a 9% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad), blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk, and probed with rabbit anti-His6 antibody (1 μg/ml) or anti-serpin B13 mAb (1 μg/ml), followed by HRP-linked protein A (1:2000; Sigma) and goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:10,000; GE Healthcare), respectively. To determine the level of expression of CD19, B cells were isolated from the pancreatic lymph nodes (PLNs) and processed using methods similar to those used for 293T cell transfectants. The blots were stained with rabbit anti-CD19 polyclonal IgG (4 μg/ml; M-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by HRP-linked protein A (1:2000). To determine the level of expression of CD4, T cells were isolated from the PLNs by sorting and lysed as described above. The blots were then stained with two different antibodies against CD4: 1) C-18 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a goat polyclonal IgG (1:1000), followed by HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat polyclonal IgG (1:1000); and 2) J15 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), a rat monoclonal IgG, followed by goat anti-rat polyclonal IgG (1:10,000). The immunoblots were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences).

Measurement of Substrate Cleavage by Cathepsin

Cathepsin L (final dilution of 1:5000; Calbiochem) was incubated in an appropriate buffer (50 mm sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 4 mm DTT, and 1 mm EDTA) at 25 °C for 45 min either alone or in the presence of purified serpin B13 (final concentration of 1.5 μg/ml; GenScript). We also added anti-serpin B13 mAb or control IgG (final concentration of 10 ng/ml) to the two reaction mixtures. The cleavage by cathepsin L in vitro was determined by adding the fluorescent substrate (carboxybenzyl-Phe-Arg)2-rhodamine 110 (final concentration of 1 μm) and measuring its rate of hydrolysis over time using a FLUOstar OPTIMA microplate reader. The hydrolysis was followed by measuring the fluorescence of the cleaved substrate every 20 s for 20 min. The data are presented as -fold induction of the peak fluorescence value over the background with the substrate alone. To assay cathepsin-mediated hydrolysis in the tissue, the pancreases were digested using collagenase P/DNase I (Roche Applied Science) and homogenized using a VWRTM pellet mixer (VWR International) in the cell lysis buffer that was supplied with the cathepsin L activity assay kit (BioVision). The lysates were incubated with substrate labeled with amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin. The amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin cleaved by cathepsin L was read using a Synergy MX fluorescence microplate reader (BioTek) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 400 and 505 nm, respectively. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay in all samples to normalize that data.

Isolation of Islets and Pancreatic Tissue

Pancreatic islets were isolated using the collagenase/DNase I digestion method and handpicked under a stereomicroscope. Islet cell suspensions were obtained by treating the islets with Cellstripper buffer (Invitrogen catalog no. 25-056-Cl) for 5 min at 37 °C. We used 100 μl of tissue digest to analyze protease activity in the pancreas.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using the t test (see Figs. 2C and 6) and a one-way analysis of variance test (see Figs. 2B, 3, and 4 and supplemental Fig. S3). A p value <0.05 was used to indicate significance. Data are presented as means ± S.D.

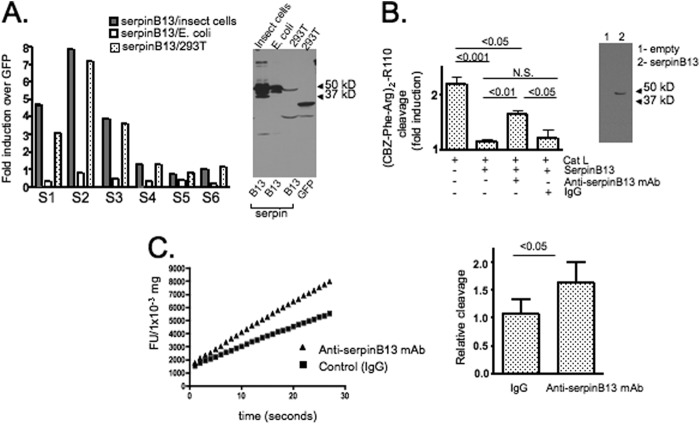

FIGURE 2.

Effect of anti-serpin B13 mAb on protease targets. A, serum-binding activity of serpin B13 in NOD mice isolated from different sources. Left panel, serum samples that were positive (S1–S3; n = 3) or negative (S4–S6; n = 3) for binding to serpin B13 produced in 293T cells were analyzed to determine the binding characteristics of this molecule produced in insect cells and E. coli as indicated. The assay was performed exactly as described previously (15), and data are expressed as -fold induction and represent the total -fold induction minus the -fold induction due to serum-binding activity in the presence of beads precoated with a control lysate (293T cells transfected with GFP). Luminex beads were loaded with 10–20 μg of purified protein or 1–2 ml of cell lysates. Right panel, Western blot analysis of purified proteins (0.5 μg of protein/lane in the first and second lanes) or cell lysates corresponding to 293T cells transfected with serpin B13 or GFP (50 μl of cell lysate/lane in the third and fourth lanes) that were used to perform the serum-binding activity assay depicted in the left panel. The blot was stained with anti-His6 polyclonal antibody. B, left panel, cleavage of the (carboxybenzyl-Phe-Arg)2-rhodamine 110 ((CBZ-Phe-Arg)2-R110) substrate by cathepsin L (Cat L) in the presence of serpin B13 produced in insects and anti-serpin B13 mAb as indicated. Data are expressed as -fold induction of maximum fluorescence over the background (which was measured in the presence of the substrate alone). The average of three experiments described is shown. Right panel, Western blot analysis of serpin B13 staining with mAb raised against mouse serpin B13. The lysates of 293T cells transfected with either an empty vector (lane 1) or mouse serpin B13 (lane 2) were analyzed. N.S., not significant. C, in vivo effect of anti-serpin B13 mAb on cathepsin L in the pancreases of female NOD mice treated with anti-serpin B13 mAb (n = 4) or control IgG (n = 4). Four-week-old animals were injected four times intravenously (100 μg/injection) over a 10-day period. Representative analysis is depicted in the left panel, and results from three independent experiments are summarized in the right panel. The error bars indicate S.D. FU, fluorescence units.

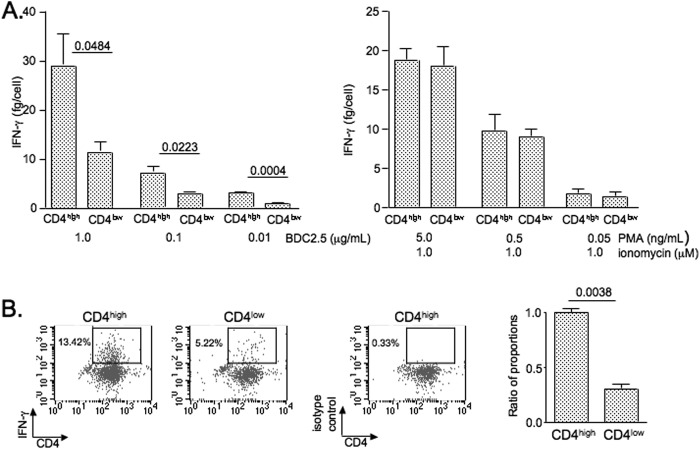

FIGURE 6.

Diminished secretion of IFN-γ in T cells with a cleaved form of the CD4 (CD4low) molecule. A, CD4high and CD4low T cells were isolated from the PLNs of BDC2.5 TCR transgenic NOD mice by sorting cells that positively stained with FITC-conjugated anti-Vβ4 TCR chain mAb (1:500) and PE-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb (1:800). The cells were then stimulated with different concentrations of the BDC2.5 mimotope in the presence of antigen-presenting cells (left panel) or phorbol esters (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)) and ionomycin (right panel). At 48 h after initiation of stimulation, the cells were counted, and culture supernatants were examined by ELISA for IFN-γ concentration. The average of three independent experiments described is shown. B, after stimulation for 72 h with the BDC2.5 mimotope-pulsed antigen-presenting cells, the cells were rested for 48 h and then restimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (10 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μm). The GolgiStop reagent was added during the last 8 h of secondary culture. The cytokine production was examined by intracellular staining of cells with allophycocyanin-conjugated mAb against IFN-γ (1:100). The data are representative of three independent experiments. The error bars indicate S.D.

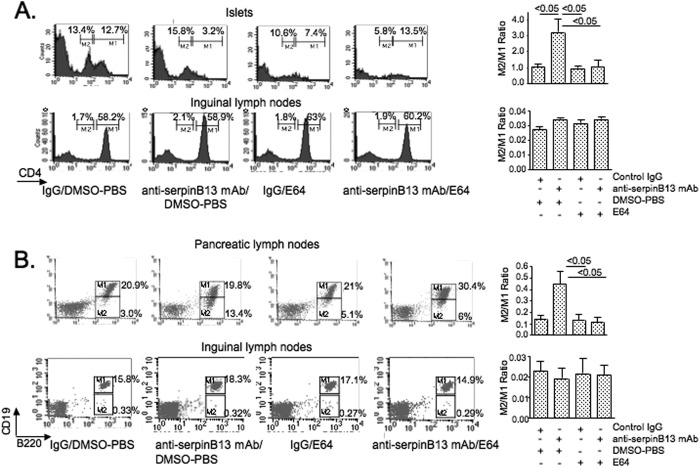

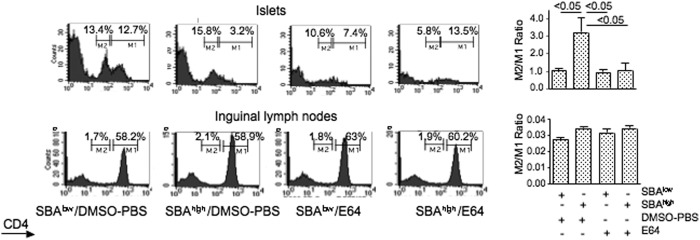

FIGURE 3.

Effect of anti-serpin B13 mAb on CD4 and CD19 in pancreas-associated lymphocytes. A, left panels, FACS analysis of CD4 expression in the islets and inguinal lymph nodes of NOD mice treated with control IgG (n = 4), anti-serpin B13 mAb (n = 4), the E64 protease inhibitor (n = 4), or both anti-serpin B13 and the E64 inhibitor (n = 4). Over a 10-day period, 4-week-old mice (prescreened for the low levels of anti-serpin autoantibodies) were injected four times intravenously with mAb or control IgG (100 μg/injection) and 10 times intraperitoneally with E64 (10 mg/kg) or diluent as indicated. Animals were killed, and cell suspensions obtained from their organs were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb at 1:800. This dilution of anti-CD4 mAb allowed us to distinguish between high (M1) and low (M2) rates of expression of CD4 in T cells. Right panels, the average of three experiments is shown. Data are expressed as the ratio between populations with low and high CD4 expression. B, left panels, FACS analysis of B220 and CD19 expression in the pancreatic and inguinal lymph nodes of NOD mice treated with anti-serpin B13 mAb and/or E64 (n = 8) exactly as described for A. Animals were killed, and their lymph nodes were stained with PE-conjugated anti-B220 mAb (1:200) and FITC-conjugated anti-CD19 mAb (1:100). The M1 and M2 regions depict high and low CD19 expressers, respectively. Right panels, the average of three experiments described is shown. Data are expressed as the ratio between populations with low versus high rates of CD19 expression. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of anti-serpin B13 natural autoantibodies on CD4 in the pancreas-associated lymphocytes. Left panels, analysis of CD4 expression in 4-week-old female NOD mice that had been prescreened for low (SBAlow) or high (SBAhigh) secretion of anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies and received either E64 or diluent (PBS) for 10 consecutive days exactly as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The animals were killed, and cell suspensions obtained from their organs were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD4 mAb at 1:800. This dilution of anti-CD4 mAb allowed us to distinguish between high (M1) and low (M2) rates of expression of CD4 in T cells. Each histogram was generated by examining four animals. Right panels, the average of three experiments described is shown. The data are expressed as the ratio between populations with low versus high rates of CD4 expression. The errors bars indicate S.D. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

RESULTS

Serpin B13 Is Expressed in the Pancreas

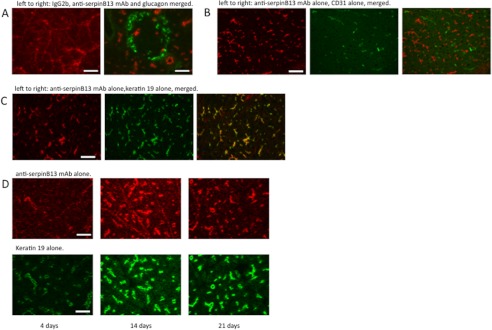

Previous analysis revealed that serpin B13 is expressed in the pancreas, although the exact tissue compartment in which it is likely to be found remained unclear (15). To identify this compartment, we stained frozen sections of NOD pancreatic tissue using a mAb that was produced in our laboratory (15). We found that a small amount of serpin B13 was expressed in the pancreatic islets (Fig. 1A), but a much larger amount was present in the exocrine pancreas. Specifically, keratin-19-positive ductal cells were more deeply stained with anti-serpin B13 mAb compared with the acini (Fig. 1, A–C). Of note, this pattern of staining did not appear to be due to the cross-reactivity of our anti-serpin mAb because it failed to stain purified keratin-19 (supplemental Fig. S1). We also observed a strong induction of serpin B13 in the pancreas during the first few weeks of life (Fig. 1D). This early expression pattern may be responsible, in part, for the generation of a humoral response to serpin B13 in young NOD mice (15).

FIGURE 1.

Expression of serpin B13 in the pancreas. Shown is the costaining of frozen pancreatic sections obtained from 6-week-old NOD mouse with anti-serpin B13 mAb and antibodies directed against glucagon (A), CD31 (B), and keratin-19 (C). Staining with the isotype control IgG2b failed to produce the pattern seen with anti-serpin B13 mAb (A, left panel). D, time course of serpin B13 expression at a young age. Pancreases from 4-, 14-, and 21-day-old NOD mice were stained with mAbs against serpin B13 (upper panels) and keratin-19 (lower panels). Scale bars = 50 μm (A and D) and 100 μm (B and C).

Anti-serpin B13 mAb Influences Protease(s) in the Pancreatic Tissue

We hypothesized that anti-serpin B13 autoantibody might influence the development of pathologic changes in the islets directly by binding to serpin B13 and by changing the ability of proteases to cleave their substrates. Initial support for this hypothesis was provided through our finding that the serpin B13 produced in 293T or insect cells was a better target for autoantibodies than the serpin B13 purified from bacteria (Fig. 2A). Although the concentration of serpin B13 in the 293T cell lysate appeared to be much lower compared with the purified serpin B13 (Fig. 2A, right panel), we adjusted for this difference during loading of the Luminex beads with antigen by using a larger volume of the cell lysate, i.e. 2 ml versus 100 μl of the purified form. Together, the data shown in Fig. 2A suggest that anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies mainly recognize properly folded or post-translationally modified epitopes and thus may neutralize the inhibitory effect of ov-serpins on their protease targets. Consistent with this finding, we determined that, in vitro, anti-serpin B13 mAb partially prevented cathepsin L-mediated cleavage of the fluorescent substrate (carboxybenzyl-Phe-Arg)2-rhodamine 110 from inhibition by serpin B13 that was produced in inset cells (Fig. 2B).

To gain additional insight into the effect of anti-serpin activity on proteases in vivo, we injected young NOD mice with anti-serpin B13 mAb and analyzed the function of cathepsin L in pancreatic tissue. Consistently with the in vitro observations, we found that cathepsin L was enhanced in the pancreases of mice that received anti-serpin B13 mAb (Fig. 2C).

Both Monoclonal Antibody and Natural Autoantibodies against Serpin B13 Up-regulate Cleavage of Lymphocyte Surface Molecules in the Pancreas

It is possible that enhanced proteolysis results in injury to leukocytes accumulating in the endocrine compartment of the pancreas and helps limit the inflammatory response in that compartment. Therefore, we looked for markers of antibody-enhanced proteolysis that could explain reduced inflammation. The initial in vitro screen revealed that exposure of mouse splenocytes to cathepsin L resulted in a partial or complete loss (due to the cleavage) of several important surface lymphocyte markers, including CD4 and CD19, but had only a minimal effect on other surface molecules (supplemental Fig. S2). This provided a rationale to study the expression profiles of CD4 and CD19 in greater detail in NOD mice treated with anti-serpin B13 mAb. We found that a broad spectrum of expression of CD4 and CD19 exists in both the islets and PLNs and that anti-serpin B13 mAb exposure caused a significant shift that favored cells expressing low-to-intermediate amounts of these markers. However, this shift was abolished in animals that received anti-serpin B13 mAb in the presence of the protease inhibitor E64 (Fig. 3, A and B), which maintained its blocking activity under the experimental conditions used (supplemental Fig. S3). These changes were observed in the pancreas and PLNs but not in the distant lymphoid organs (e.g. inguinal lymph nodes). Together, these data suggest that the protease activity is important for anti-serpin antibodies to cause the shift toward cells expressing low levels of CD4 and CD19.

It is possible that the effects of anti-serpin B13 mAb do not exactly reflect the effects of elevated levels of natural anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies. To address this problem, we compared NOD mice with distinct levels of anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies. We found that young animals with high levels of endogenous anti-serpin B13 autoantibodies (SBAhigh) had a markedly reduced population of islet-associated CD4high cells compared with animals with low levels of these autoantibodies (SBAlow). The number of islet-associated CD4high cells did not decrease, however, in SBAhigh mice that received the protease inhibitor E64 (Fig. 4). This observation suggests that natural anti-serpin autoantibodies regulate proteases in vivo in a fashion similar to that described for anti-serpin B13 mAb.

To verify that the considerably reduced levels of CD19 on the cell surface are a sign of degradation, we performed a Western blot analysis of CD19 in B220+/CD19+ B cells isolated from inguinal lymph nodes and from PLN B cells expressing either high or low amounts of CD19. The B220+/CD19+ B cells isolated from the inguinal lymph nodes (R1) expressed only the non-degraded form of CD19, whereas the B220+/CD19+ B cells isolated from the PLNs (R2) contained both the degraded and non-degraded (cleaved) forms of CD19. The B220+/CD19low cells from the PLNs (R3) had no intact CD19 molecules; in fact, CD19 molecules were quantitatively and qualitatively more severely degraded in the B220+/CD19low cells compared with the B220+/CD19high cells (Fig. 5A). We also isolated T cells from the PLNs based on their limited expression of CD4 (R3). These cells underwent Western blot analysis and then staining with one antibody that recognizes an extracellular domain of CD4 and another that recognizes an intracellular domain of CD4 (Fig. 5B). The extracellular domain was not detected in the isolated T cells (R3), but the stain for the intracellular domain was positive, indicating that these cells do express CD4. Thus, our findings demonstrate that B220+/CD19low B cells and CD4low T cells accumulate in the PLNs and pancreatic islets in response to anti-serpin B13 antibody-induced augmentation of proteases and increased cleavage of the extracellular portion of CD19 and CD4.

T Cells with the Cleaved Form of CD4 Secrete Less IFN-γ Compared with T Cells Expressing the Intact CD4 Molecule

To determine the significance of changes that are caused by anti-serpin B13 antibodies in lymphocytes, we isolated CD4low and CD4high T cells from the PLNs of BDC2.5 TCR transgenic NOD mice and compared these two cell populations for their ability to secrete cytokines. We focused on IFN-γ because this cytokine was heavily implicated in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes (21). We found that during both the primary and secondary stimulation with an antigenic peptide, T cells with the truncated form of CD4 produced significantly less IFN-γ compared with T cells expressing normal levels of the CD4 molecule (Fig. 6, A, left panel, and B). This defect was not observed during stimulation (Fig. 6A, right panel), which does not require CD4.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated the existence of a novel antibody that recognizes and inhibits the protease inhibitor serpin B13 in the setting of autoimmune diabetes. This antibody leads to marked histological changes in the composition of the inflammatory infiltrate in the pancreatic islets of NOD mice and ultimately contributes to a better clinical outcome (15). In this study, we found that serpin B13 is expressed mainly in the exocrine portion of the pancreas, most notably in the epithelial lining of the pancreatic ducts. This pattern of expression suggests that the protease targets of serpin B13 (e.g. cathepsins L and K) are also expressed in this tissue compartment. Although this possibility was not addressed in this study, it is supported by reports from other studies in which the expression of cathepsin K was detected in the bronchial and bile duct epithelial cells and in the urothelia (22, 23).

The features of the protective mechanism of anti-serpin antibody are the inhibition of serpin B13 and the consequent maintenance of the limited function of its protease targets, which in turn facilitate the cleavage of cell-surface molecules expressed in lymphocytes, including the extracellular domains of CD4 and CD19. Our conclusion that proteases mediate a serpin B13 antibody-induced shift toward cells expressing low levels of CD4 and CD19 stems from observations that the protease inhibitor E64 prevented this change. On the other hand, the E64 inhibitor failed to decrease the number of CD4low and CD19low expressers in the absence of anti-serpin antibodies (Figs. 3 and 4). A possible explanation for this is that, in our experimental system, serpin B13 and E64 may have competed for the same, relatively limited pool of extracellular cysteine proteases. According to this model, NOD mice with very low levels of endogenous anti-serpin autoantibodies would have sufficient levels of functional serpin B13 to block most of the target proteases; thus, the inhibitory effect of E64 would not have been seen under these conditions. Consequently, disengagement of serpin molecules with endogenous autoantibodies (or a mAb) would increase access of E64 to protease targets and allow for a better demonstration of its inhibitory properties.

It is likely that molecules other than CD4 and CD19 are also cleaved by anti-serpin B13 antibody-enhanced proteases. Consistent with this hypothesis are other studies in which the investigators demonstrated that 1) administration of exogenous hydrolytic enzymes can lead to a partial resolution of inflammation (3, 4), 2) proteolytic enzymes can impair the function of many different cell-surface molecules expressed in inflammatory cells (24), and 3) the expression of CD25 in regulatory T cells is markedly reduced at the site of inflammation (25, 26). Of note, other autoantibodies have been found to be associated with protection from type 1 diabetes (27–29), although the exact molecular events following their mode of action have not been determined.

It should be noted that anti-clade B serpin autoantibodies may slow down development of the autoimmune form of diabetes by other mechanisms. For example, an anti-serpin autoantibody-mediated up-regulation of proteases may lead to pancreatic islet tissue injury, followed by the compensatory regeneration of islet tissue, de novo formation of islets, or both (30). Support for this hypothesis has been provided through the observations that cathepsin K (31) and cathepsin L (32, 33) play important roles in tissue remodeling and that the expression of transcription factors associated with the differentiation of pancreatic islets is increased in NOD mice treated with anti-serpin B13 mAb (data not shown). Another possibility for protective mechanisms that are delivered by anti-serpin antibodies may involve 1) induction of neonatal β-cell apoptosis and immunological tolerance to molecules released from dying cells (34) and 2) generation of the biologically active form of transforming growth factor-β, which is responsible for generating regulatory T cells with anti-inflammatory properties (35).

In addition to the evidence presented in this study that the preservation of proteases in the pancreas helps to keep inflammation in check and in another study that the cathepsin L gene belongs to a group of the 100 “protective genes” in NOD mice (36), it has been demonstrated that down-regulation of proteases using chemical inhibitors (37, 38), genetic knock-out techniques (39, 40), or natural serpin inhibitors (41, 42) can block inflammation in the pancreatic islets of NOD mice. We would like to argue that by using a mAb against serpin B13 and the E64 inhibitor, which has limited cell permeability, we were able to explore primarily the role of extracellular proteases in the regulation of inflammation, despite the fact that protease targets of serpin B13 (e.g. cathepsins L and K) are located mainly in the lysosomal and endosomal vesicles. There is ample evidence that these cathepsins can be secreted to process proteins in the extracellular matrix, where they can promote tissue remodeling (43, 44). Cathepsin L can be active at a close-to-neutral pH, and both hypoxia and acidification that are associated with inflammation can increase the stability of proteases. By contrast, the proteases manipulated in other studies may have been both extracellular and intracellular (37, 38), and the manipulation of those proteases may have affected multiple tissues over extended periods of time (39, 40). As for α1-antitrypsin (41, 42), this serpin neutralizes proteases other than those regulated by serpin B13; thus, its anti-diabetic effect may reflect the inhibition of additional proteases.

In conclusion, anti-clade B serpin antibodies induced under inflammatory conditions can fine-tune the balance between proteases and their inhibitors in damaged tissue and may thus contribute to homeostatic events that subdue the early stages of inflammation. If so, the protocols designed to enhance humoral immunity against clade B serpins should impede the progression of pathologic changes that occur in autoimmune diabetes and in other forms of inflammatory disease.

This work was supported by a Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center grant (to J. C.) and a Translational and Interdisciplinary Research pilot grant from Yale University (to J. C. and O. H.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- NOD

- nonobese

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- PE

- phycoerythrin

- PLN

- pancreatic lymph node.

REFERENCES

- 1. Luke C. J., Pak S. C., Askew Y. S., Naviglia T. L., Askew D. J., Nobar S. M., Vetica A. C., Long O. S., Watkins S. C., Stolz D. B., Barstead R. J., Moulder G. L., Brömme D., Silverman G. A. (2007) An intracellular serpin regulates necrosis by inhibiting the induction and sequelae of lysosomal injury. Cell 130, 1108–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Casciola-Rosen L., Andrade F., Ulanet D., Wong W. B., Rosen A. (1999) Cleavage by granzyme B is strongly predictive of autoantigen status. Implications for initiation of autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 190, 815–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Targoni O. S., Tary-Lehmann M., Lehmann P. V. (1999) Prevention of murine EAE by oral hydrolytic enzyme treatment. J. Autoimmun. 12, 191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wiest-Ladenburger U., Richter W., Moeller P., Boehm B. O. (1997) Protease treatment delays diabetes onset in diabetes-prone nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. Int. J. Immunother. 13, 75–78 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asagiri M., Hirai T., Kunigami T., Kamano S., Gober H.-J., Okamoto K., Nishikawa K., Latz E., Golenbock D. T., Aoki K., Ohya K., Imai Y., Morishita Y., Miyazono K., Kato S., Saftig P., Takayanagi H. (2008) Cathepsin K-dependent Toll-like receptor 9 signaling revealed in experimental arthritis. Science 319, 624–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reinhold D., Bank U., Täger M., Ansorge S., Wrenger S., Thielitz A., Lendeckel U., Faust J., Neubert K., Brocke S. (2008) DP1V/CD26, APN/CD13 and related enzymes as regulators of T cell immunity: implication for experimental encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Front. Biosci. 13, 2356–2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Irving J. A., Pike R. N., Lesk A. M., Whisstock J. C. (2000) Phylogeny of the serpin superfamily: implications of patterns of amino acid sequences for structure and function. Genome Res. 10, 1845–1864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silverman G. A., Whisstock J. C., Askew D. J., Pak S. C., Luke C. J., Cataltepe S., Irving J. A., Bird P. I. (2004) Human clade B serpins (ov-serpins) belong to a cohort of evolutionary dispersed intracellular proteinase inhibitor clades that protect cells from promiscuous proteolysis. Cell, Mol. Life Sci. 61, 301–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Higgins W. J., Fox D. M., Kowalski P. S., Nielsen J. E., Worrall D. M. (2010) Heparin enhances serpin inhibition of the cysteine protease cathepsin L. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3722–3729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anderson M. S., Bluestone J. A. (2005) The NOD mouse: a model of immune dysregulation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23, 447–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Solomon M., Sarvetnick N. (2004) The pathogenesis of diabetes in the NOD mouse. Adv. Immunol. 84, 239–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakashima T., Pak S. C., Silverman G. A., Spring P. M., Frederick M. J., Clayman G. L. (2000) Genomic cloning, mapping, structure and promoter analysis of HEADPIN, a serpin which is down-regulated in head and neck cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1492, 441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Welss T., Sun J., Irving J. A., Blum R., Smith A. I., Whisstock J. C., Pike R. N., von Mikecz A., Ruzicka T., Bird P. I., Abts H. F. (2003) Hurpin is a selective inhibitor of lysosomal cathepsin L and protects keratinocytes from ultraviolet-induced apoptosis. Biochemistry 42, 7381–7389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jayakumar A., Kang Y., Frederick M. J., Pak S. C., Henderson Y., Holton P. R., Mitsudo K., Silverman G. A., EL-Naggar A. K., Brömme D., Clayman G. L. (2003) Inhibition of the cysteine proteinases cathepsins K and L by the serpin headpin (SERPIN B13): a kinetic analysis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 409, 367–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Czyzyk J., Henegariu O., Preston-Hurlburt P., Baldzizhar R., Fedorchuk C., Esplugues E., Bottomly K., Gorus F. K., Herold K., Flavell R. A. (2012) Enhanced anti-serpin antibody activity inhibits autoimmune inflammation in type 1 diabetes. J. Immunol. 188, 6319–6327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spitzer R. E. (1969) Serum C3 lytic system in patients with glomerulonephritis. Science 164, 436–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gawryl M. S., Hoyer L. W. (1982) Inactivation of factor VIII coagulant activity by two different types of human antibodies. Blood 60, 1103–1109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alsenz J., Bork K., Loos M. (1987) Autoantibody-mediated acquired deficiency of C1 inhibitor. N. Engl. J. Med. 316, 1360–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jackson J., Sim R. B., Whelan A., Feighery C. (1986) An IgG autoantibody, which inactivates C1-inhibitor. Nature 323, 722–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshifuji H., Umehara H., Maruyama H., Itoh M., Tanaka M., Kawabata D., Fujii T., Mimori T. (2005) Amelioration of experimental arthritis by a calpain-inhibitory compound: regulation of cytokine production by E64 in vivo and in vitro. Int. Immunol. 17, 1327–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sarvetnick N., Liggitt D., Pitts S. L., Hansen S. E., Stewart T. A. (1988) Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus induced in transgenic mice by ectopic expression of class II MHC and interferon-γ. Cell 52, 773–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bühling F., Gerber A., Häckel C., Krüger S., Köhnlein T., Brömme D., Reinhold D., Ansorge S., Welte T. (1999) Expression of cathepsin K in lung epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 20, 612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haeckel C., Krueger S., Buehling F., Broemme D., Franke K., Schuetze A., Roese I., Roessner A. (1999) Expression of cathepsin K in the human embryo and fetus. Dev. Dyn. 216, 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roep B. O., van den Engel N. K., van Halteren A. G., Duinkerken G., Martin S. (2002) Modulation of autoimmunity to β-cell antigens by proteases. Diabetologia 45, 686–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang Q., Adams J. Y., Penaranda C., Melli K., Piaggio E., Sgouroudis E., Piccirillo C. A., Salomon B. L., Bluestone J. A. (2008) Central role of defective interleukin-2 production in the triggering of islet autoimmune destruction. Immunity 28, 687–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lazarski C. A., Hughson A., Sojka D. K., Fowell D. J. (2008) Regulating Treg cells at sites of inflammation. Immunity 29, 511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. She J.-X., Ellis T. M., Wilson S. B., Wasserfall C. H., Marron M., Reimsneider S., Kent S. C., Hafler D. A., Neuberg D. S., Muir A., Strominger J. L., Atkinson M. A. (1999) Heterophile antibodies segregate in families and are associated with protection from type 1 diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 8116–8119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Menard V., Jacobs H., Jun H.-S., Yoon J.-W., Kim S. W. (1999) Anti-GAD monoclonal antibody delays the onset of diabetes mellitus in NOD mice. Pharm. Res. 16, 1059–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koczwara K., Bonifacio E., Ziegler A.-G. (2004) Transmission of maternal islet antibodies and risk of autoimmune diabetes in offspring of mothers with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 53, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miralles F., Battelino T., Czernichow P., Scharfmann R. (1998) TGF-β plays a key role in morphogenesis of the pancreatic islets of Langerhans by controlling the activity of the matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2. J. Cell Biol. 143, 827–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boyce B. F., Xing L., Yao Z., Shakespeare W. C., Wang Y., Metcalf C. A., 3rd, Sundaramoorthi R., Dalgarno D. C., Iuliucci J. D., Sawyer T. K. (2006) Future anti-catabolic therapeutic targets in bone disease. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1068, 447–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Afonso S., Romagnano L., Babiarz B. (1997) The expression and function of cystatin C and cathepsin B and cathepsin L during mouse embryo implantation and placentation. Development 124, 3415–3425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Robker R. L. (2000) Progesterone-related genes in the ovulation process: ADAMTS-1 and cathepsin L proteases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4689–4694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hugues S., Mougneau E., Ferlin W., Jeske D., Hofman P., Homann D., Beaudoin L., Schrike C., Von Herrath M., Lehuen A., Glaichenhaus N. (2002) Tolerance to islet antigens and prevention from diabetes induced by limited apoptosis of pancreatic β cells. Immunity 16, 169–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pesu M., Watford W. T., Wei L., Xu L., Fuss I., Strober W., Andersson J., Shevach E. M., Quezado M., Bouladoux N., Roebroek A., Belkaid Y., Creemers J., O'Shea J. J. (2008) TGF T-cell-expressed proprotein convertase furin is essential for maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance. Nature 455, 246–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu W., Wojtkiewicz G., Weissleder R., Benoist C., Mathis D. (2012) Early window of diabetes determinism in NOD mice, dependent on the complement receptor CRIg, identified by noninvasive imaging. Nat. Immunol. 13, 361–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ishimaru N., Arakaki R., Katunuma N., Hayashi Y. (2004) Critical role of cathepsin-inhibitors for autoantigen processing and autoimmunity. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 44, 309–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamada A., Ishimaru N., Arakaki R., Katunuma N., Hayashi Y. (2010) Cathepsin L inhibition prevents murine autoimmune diabetes via suppression of CD8+ T cell activity. PloS ONE 5, e12894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maehr R., Mintern J. D., Herman A. E., Lennon-Duménil A.-M., Mathis D., Benoist C., Ploegh H. L. (2005) Cathepsin L is essential for onset of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2934–2943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hsing L. C., Kirk E. A., McMillen T. S., Hsiao S. H., Caldwell M., Houston B., Rudensky A. Y., LeBoeuf R. C. (2010) Roles of cathepsin S, L, and B in insulitis and diabetes in the NOD mouse. J Autoimmun. 34, 96–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu Y., Tang M., Wasserfall C., Kou Z., Campbell-Thompson M., Gardemann T., Crawford J., Atkinson M., Song S. (2006) α1-Antitrypsin gene therapy modulates cellular immunity and efficiently prevents type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 17, 625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Koulmanda M., Bhasin M., Hoffman L., Fan Z., Qipo A., Shi H., Bonner-Weir S., Putheti P., Degauque N., Libermann T. A., Auchincloss H., Jr., Flier J. S., Strom T. B. (2008) Curative and β cell regenerative effects of α1-antitrypsin treatment in autoimmune diabetic NOD mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16242–16247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reiser J., Adair B., Reinheckel T. (2010) Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3421–3431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dickinson D. P. (2002) Cysteine peptidases of mammal: their biological roles and potential effects in the oral cavity and other tissues in health and disease. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 13, 238–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]