Background: Calcium influx (ICRAC) is important for proper cell function.

Results: A novel STIM1 mutant increases ICRAC, Ca2+-dependently destabilizes Orai1, and alters clustering. A new mathematical model explains the phenotype.

Conclusion: The molecular kinetics of STIM1 and Orai1 are major determinants of ICRAC.

Significance: The diffusion trap model and alteration of Orai1 stability provide a tool for understanding ICRAC regulation.

Keywords: Calcium Channels, Calcium Imaging, Calcium Signaling, Glycosylation, Protein Degradation, Monte Carlo Simulation, Orai1, STIM1, TIRF, Diffusion Trap

Abstract

A drop of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ concentration triggers its Ca2+ ssensor protein stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) to oligomerize and accumulate within endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions where it activates Orai1 channels, providing store-operated Ca2+ entry. To elucidate the functional significance of N-glycosylation sites of STIM1, we created different mutations of asparagine-131 and asparagine-171. STIM1 NN/DQ resulted in a strong gain of function. Patch clamp, Total Internal Reflection Fluorescent (TIRF) microscopy, and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analyses revealed that expression of STIM1 DQ mutants increases the number of active Orai1 channels and the rate of STIM1 translocation to endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions with a decrease in current latency. Surprisingly, co-expression of STIM1 DQ decreased Orai1 protein, altering the STIM1:Orai1 stoichiometry. We describe a novel mathematical tool to delineate the effects of altered STIM1 or Orai1 diffusion parameters from stoichiometrical changes. The mutant uncovers a novel mechanism whereby “superactive” STIM1 DQ leads to altered oligomerization rate constants and to degradation of Orai1 with a change in stoichiometry of activator (STIM1) to effector (Orai1) ratio leading to altered Ca2+ homeostasis.

Introduction

Orai1 Ca2+ channels are important gateways for Ca2+ entry following receptor-mediated phospholipase C-dependent depletion of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-sensitive4 Ca2+ stores. Activation of T cells through binding and dimerization of T cell receptors with antigen-loaded major histocompatibility complexes of antigen presenting cells is one example of such a signal that results in phospholipase Cγ-mediated production of IP3 and diacylglycerol. The resulting inward Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current (ICRAC) controls not only ubiquitous cellular functions, e.g. proliferation and apoptosis, but also cell specific functions such as cytokine production or target cell killing (1–3). The importance of ICRAC for the immune response is highlighted by the severe combined immunodeficiency in patients and mice with defective store operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) (4–7). To initiate SOCE, the luminal domain of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized STIM1 proteins dissociate their EF-hand-bound Ca2+ ions in response to ER Ca2+ release, thereby initiating a conformational change, oligomerization, and subsequent movement to ER-PM junctions. The new conformation unfolds C-terminally localized coiled-coil regions of STIM1 and enables interaction of the C-terminal lysine-rich repeat with plasma membrane (PM) lipids. The thereby exposed interaction domain (named either CRAC activation domain (CAD), STIM1 Orai1-activating region (SOAR) or ORAI1-activating small fragment (OASF)) directly interact with and trap Orai1 channels (8–10), which are initially evenly distributed within the PM (11). The domains of clustered STIM1/Orai1 molecules are the sites of Ca2+ influx (12–14). The minimal requirement for activation are two STIM1 molecules bound per Orai1 tetramer; however, this stoichiometry results in channels with very low open probability (Po), whereas maximal Po is achieved with eight bound STIM1 proteins per Orai1 tetramer (15, 16). Failure to activate this Ca2+ entry pathway either by defective STIM1 molecules or by mutations in Orai1 proteins results in severe defects in immune cell function but also in defective skin, platelet, and neuronal functions, among others (5, 17, 18). More moderate physiological and pathophysiological changes in immune cell function occur during aging, but also in autoimmunity and cancer. One mechanism to alter immune cell function arises from the degree and pattern of glycosylation in immune cells (19, 20). Although many immune cell surface receptors show complex glycosylation patterns, one alternative target to affect immune cell function by changes in glycosylation may involve altering proteins that regulate SOCE. In this study, we investigate the individual contributions of altered glycosylation status of ICRAC-mediating proteins and of possibly glycosylation-independent functional changes of mutations within the sterile α motif (SAM) domain of STIM1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Orai1 Stable Cell Lines

An Orai1 stable cell line was generated by transfecting HEK293 or Jurkat E6.1 T cells with N-terminally HA-tagged Orai1. The expression vector pGK-Puro-MO70 (21) was modified by deleting Orai3 and the CITE-EGFP sequence. Orai1 coding sequence was amplified with the forward primer 3′-gggctcgaggccGCCACCATGCATCCGGAGCCCGC-5′ and the reverse primer 3′-gggctcgagTCAGGCATAGTGGCTGCCGG-5′, adding the HA tag and XhoI recognition site that has been used for cloning into the vector. Stable cells were selected using either 1 μg/ml puromycin (HEK) or 2 μg/ml (Jurkat).

Cell Culture

HEK293 cells were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator in minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin-streptomycin. HEK293 cells were passaged by treatment with trypsin/EDTA.

Constructs and Transfection

All hOrai and hStim constructs were subcloned into pCAGGS-IRES-GFP or pCAGGS-IRES-RFP. Tagged constructs were subcloned in pMAX (C) RFP, pMAX (C) GFP, or YFP (N) pEX vectors. Mutagenesis was performed by QuikChange PCR (Stratagene). Mutations in hOrai1 were conducted in the hOrai1-SmaI fragment subcloned in pBlue script. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. For transfection, the indicated amount of DNA (0.5 μg of Orai1 and 1.5 μg of STIM1 unless otherwise indicated) was electroporated into HEK293 cells with Nucleofactor II electroporator and kit V (Lonza). The cells were transfected according to the manufacturer's instructions and seeded 24 h before measurements. For biochemical methods, HEK293 cells were transfected at 70–80% confluency with corresponding plasmids using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science). The total sizes of Orai1 and Stim1 plasmids were 7070 and 8212 bp, respectively and the amounts of transfected DNA were converted into moles using an online conversion application.

Cell Surface Biotinylation

For detection of surface proteins, transfected cells were harvested after 48 h, washed twice with 10 ml of PBS phosphate buffered saline containing 1 mm MgCl2 and 0.5 mm CaCl2, pH 8) and incubated with NHS-Biotin (0.5 mg/ml) for 30 min at 4 °C. Unbound biotin was quenched with PBSB (PBS with 0.1% BSA, pH 8). Cells were harvested with 2 mm EDTA in PBS, pH 7.4, washed with PBS, and lysed in PBS containing 1% Triton, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.4, with freshly added protease inhibitors. Protein content of cell lysate was determined by the BCA method (Pierce). Cell lysates containing 1 mg of total protein were incubated with avidin beads (Pierce) on a rotating wheel at 4 °C for 3 h and then washed with lysis buffer containing 0.25 m NaCl to remove unbound protein. Alternatively, for more stringent conditions, avidin beads were washed with 1 mm urea and 7 m thiourea followed by a final 0.75 m NaCl wash. Biotinylated fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot.

Cell Lysates and Antibodies

For analysis of expression levels paralleling patch clamp analyses, transfected HEK293 cells were lysed after 24 h. Lysis buffer contained 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxcholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mm Tris, pH 8, supplemented with protease inhibitors. 50–75 μg of the total proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and proteins were electrotransferred on nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes. Immunoblots were probed with anti-Orai1 (Sigma; 1:2000), anti-STIM1 (BD Biosciences; 1:250 or 1:500), anti-HA (Roche Applied Science; 1:1000), anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling; 1:2000), or anti-γ-tubulin (Sigma; 1:1000) antibodies. Specificity of the anti-Orai1 antibody was also confirmed in native tissue using siRNA against Orai1 (22).

Electrophysiology

Recordings were performed at room temperature in the tight seal whole cell configuration. Recording electrodes with a resistance of 2–3 MΩ were used and coated with Sigmacote. Pipette and cell capacitance were electronically compensated before each voltage ramp with an EPC-10 patch clamp amplifier controlled by Patchmaster software (HEKA). Series resistance was compensated to 85% for the transfected HEK293 cells. Immediately after establishing whole cell configuration, linear voltage ramps from −150 to +150 mV (50-ms duration) were applied every 2 s from a holding potential of 0 mV for the indicated time period. Membrane currents were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 2.9 kHz. For leak current correction, the ramp current before CRAC activation was subtracted. Voltages were corrected for a liquid junction potential of 10 mV in standard bath solution and of 17 mV for NMDG-containing solution. Currents were analyzed at −140 mV and 110 s after break-in, unless otherwise indicated. The currents were normalized to whole cell capacitance, and significant outliers (p < 0.05; Grubb's test) were excluded. The pipette solution for fast activation contained the following: 120 mm cesium glutamate, 3 mm MgCl2, 20 mm cesium BAPTA, 10 mm Hepes, and 0.05 mm IP3 (pH 7.2 with CsOH). The pipette solution for the passive depletion contained the following: 120 mm cesium aspartate, 8 mm NaCl, 10 mm EGTA, 3 mm MgCl2, and 10 Hepes (pH 7.2 with CsOH). Bath solution contained 120 mm NaCl, 10 mm tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA-Cl), 2 mm CaCl2 or 20 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm Hepes, and glucose (pH 7.2 with NaOH). Divalent free (DVF) bath solution contained the following: 120 mm NaCl, 10 mm TEA-Cl, 10 mm Hepes, 10 mm EDTA, and glucose (pH 7.2). Nominal Ca2+-free solution did not contain added CaCl2.

Apparent Open Probability Analysis and Nonstationary Noise Analysis

Normalized instantaneous tail currents for voltage steps to −100 mV after test pulses in the range of −160 to 80 mV were used to produce the apparent open probabilities (Po). To determine the amplitude of the instantaneous tail currents and to minimize the error caused by cell capacitance, tail currents were fitted with a single exponential function to the beginning of the −100 mV pulse. For noise analysis, DVF contained 155 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEDTA, 1 mm EDTA, and 10 mm Hepes (pH 7.2 with NMDG). For experiments examining the block of Na+ conducted ICRAC by Ca2+, CaCl2 was added to the divalent free solution at the appropriate amount calculated from MaxChelator software program. Protocol and analysis was used as described by Prakriya and Lewis (23).

Fluorescence-based Ca2+ Imaging

External solution contained 155 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm CaCl2 (unless otherwise indicated), 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 5 mm Hepes (pH 7.4 with NaOH). Stock solutions of thapsigargin (Tg) were prepared in Me2SO at a concentration of 1 mm. HEK293 cells grown in low density on 25-mm glass coverslips were loaded with 1 μm Fura 2-AM in minimum essential growth medium in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator for 20 min. All of the experiments were performed in a perfusion chamber with low volume and high solution exchange rate at room temperature. Images were analyzed with TILLVision software. The absolute intracellular Ca2+ concentration was estimated from the relation [Ca2+]i = K*(R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R) where the values of K, Rmin, and Rmax were determined from an in situ calibration of Fura 2-AM in HEK293 cells as described by Grynkiewicz et al. (24).

Evanescent Wave Imaging (TIRF)

HEK293 cells were split 24 h after transfection of 3 μg of YFP (N) STIM1 WT/DQ and 1 μg of Orai1 (C) RFP and seeded on 25-mm glass coverslips for 24 h before measurements. The external solution contained 155 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 5 mm Hepes (pH 7,4 with NaOH). A Leica AM TIRF MC system with a 100× 1.47 NA oil HCX PlanApo objective was used for recording fluorescence images. Excitation and analyses of YFP fluorescent proteins was achieved with a 488-nm laser and a GFP emission filter. Reflected light was collected with cooled electron multiplier charge coupled device camera (Andor iXon 885). Exposure time for YFP was 100 ms at 15% laser intensity. The penetration depth of the evanescent wave was set at 110 nm. To detect RFP, a 561-nm laser at 50% intensity and a RFP emission filter were used. Exposure time was set to 200 ms.

FRET Measurements

FRET measurements were performed in the TIRF plane with an exposure time of 200 ms and a penetration depth of 150 nm. Laser intensities between 25 and 35% were typically used. To detect the STIM1-Orai1 interaction, HEK293 cells were transfected with 3 μg of STIM1 WT/DQ (C) RFP and 1 μg of Orai1 (C) GFP; for the STIM1-STIM1 interaction, the cells were transfected with 1.5 μg of STIM1 WT/DQ (C) RFP, 1.5 μg of STIM1 WT/DQ (C) GFP, and 0.5 μg of Orai1. Stores were depleted incubating the cells for 10 min with 1 μm Tg. FRET was evaluated using the normalized FRET method of Van Rheenen et al. (38). FRET images were corrected for cross-talk, direct excitation, and background. Calibration values were obtained every day of measurements from cells expressing only the GFP- or RFP-labeled constructs. All of the experiments were performed at room temperature.

Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleach (FRAP)

Confocal imaging was performed on multibeam confocal scanner systems (VTinfinity-3; VisiTech Int., Sunderland, UK) using a 60× oil immersion objective. Images were acquired at room temperature in the 2 mm Ca2+ solution used for Ca2+ imaging. For monitoring recovery after stimulation, the cells were treated with 1 μm Tg in a Ca2+-free solution for 10 min before imaging in the same solution. To induce bleaching, the intensity of a 491-nm laser was set to 100% and directed to a predefined region within the cell for 7 s. Initial fluorescence and recovery after photobleach were measured by scanning across the bleached region at a laser intensity of 40% for 100 ms and a frequency of 1 Hz. Recovery was monitored over 5 min. After acquisition, the data were transferred into ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) for further processing. To correct for autobleaching effects, fluorescence intensity was integrated over a region overlaying the photobleached profile and a nonbleached control region. The changes in ratio between the two regions were plotted over time. The relative intensity before and immediately after photobleaching were set to 1 and 0, respectively. Time constants (τ) were calculated for each cell by fitting the resulting curve with an exponential function using Igor software (Wavemetrics).

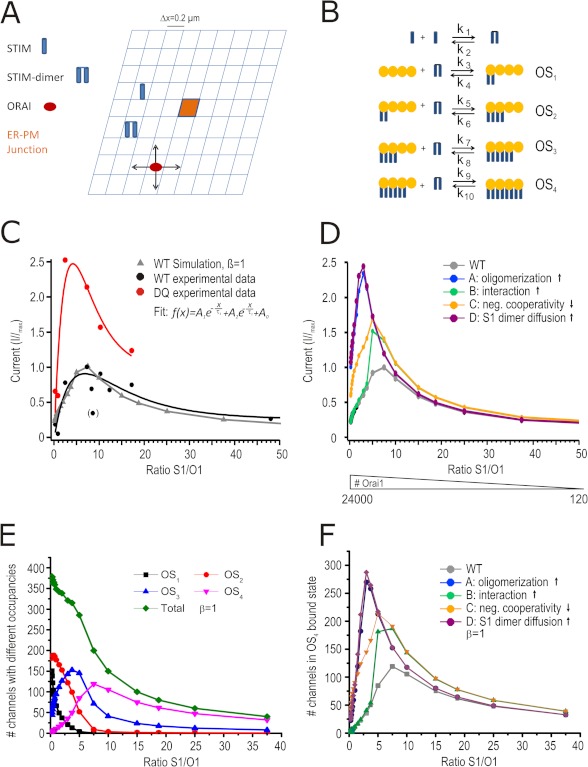

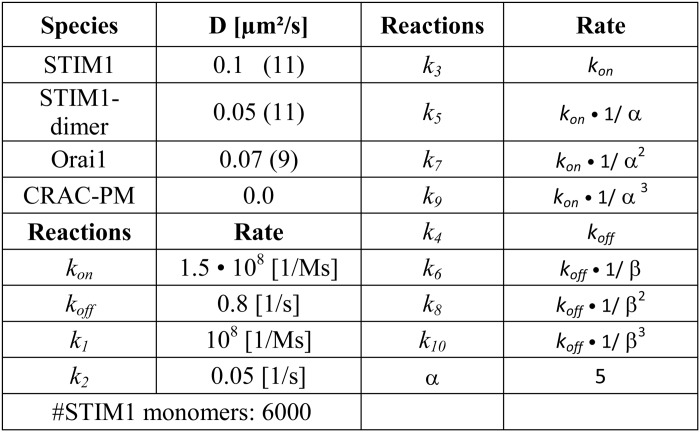

A Model to Describe CRAC Channel Activation by STIM1 WT and STIM1 Mutants

We describe STIM1-Orai1 interaction/oligomerization mathematically by the reaction scheme depicted in Fig. 6B and assume that all monomers/oligomers can diffuse within a two-dimensional area (Fig. 6A). The resulting reaction-diffusion system is studied by computer simulations based upon a two-dimensional Gillespie Monte Carlo Algorithm (25, 26). Because CRAC channel activation is a local process (11), we model a geometry of 15 × 15 grid cells, each describing an area of (0.2 μm)2, which represents the cell plasma membrane and the ER membrane at the same time. For the diffusion of STIM1 monomers, STIM1 dimers, and Orai1, we assume periodic boundary conditions and only at the grid cell right in the middle of our geometry (Plasma Membrane Junction; see Fig. 6A), STIM1 dimers can trap Orai1 and build up the four different CRAC channel states OS1, OS2, OS3, and OS4, consisting of one Orai1 tetramer and one to four STIM1 dimers. The STIM1 to Orai1 binding process is less probable the more STIM1 dimers are already bound to an Orai1 tetramer, which is controlled by the negative cooperativity factor α. The CRAC channel states defined in this way become more stable the more STIM1 dimers participate in forming the channel, which is quantified by the cooperativity factor β (16). Each of these four states contributes in a specific, predefined way to the total CRAC channel current, ICRAC = 0.001·OS1 + 0.025·OS2 + 0.275·OS3 + 1.0·OS4, modeling the experimentally observed graded channel currents (15, 16). The parameters (reaction rates and diffusion constants) of our model are shown in Table 1. In addition to the wild type, we model four different mutants, which differ by diffusion constants or reaction rates, to test which one fits best to the experimental results for STIM1 DQ mutants. Mutant A represents a stronger oligomerization of STIM1 monomers (10·k1(WT) = k1(A)), Mutant B represents a stronger STIM1 to Orai1 binding (10·ki(WT) = ki(B),i ∈ {3, 5, 7, 9}), Mutant C represents a decreased negative cooperativity of STIM1 to Orai1 binding (α(C) = 1.5 ≠ α(WT) = 5), and Mutant D represents faster STIM1 dimer diffusion (10·D2STIM1(WT) = D2STIM1(D)).

FIGURE 6.

STIM1 DQ phenotype can be simulated by a mathematical model. A, model geometry. The size of ER-PM junction is (0.2 μm)2. B, reaction scheme where OS(x) denotes one Orai1 tetramer with (x) STIM1 dimer bound with the corresponding reaction constants shown above the arrows. C, normalized stationary CD plotted against the STIM1/Orai1 ratio for measured STIM1 WT (black circles) and modeled (simulated) WT data (gray triangles) and for measured STIM1 DQ (red) normalized to measured WT maximum. D, normalized currents derived from the model plotted against S1/O1 ratio. The colors denote different STIM1 mutants (see text) normalized to Imax of model WT. The number of Orai1 entered into the model are noted below. E, number of channels with different occupancies plotted against S1/O1 ratio. F, number of OS4-bound channels for the different mutants plotted against S1/O1 ratio.

TABLE 1.

Model parameters

Numbers in parentheses denote a reference.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using TILL Vision (TILL Photonics), Igor Pro (Wavemetrics), LAS (Leica Application suite) Software 2.4.1, Leica FRET SE Wizard Software, Patchmaster and Fitmaster (HEKA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft). All of the values are given as the means ± S.E. The numbers of cells are given within bar graphs. In case data points were normally distributed, an unpaired two-sided Student's t test was applied. Significance was as follows: p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), or p < 0.001 (***).

RESULTS

Mutagenesis of STIM1 N-Glycosylation Sites Profoundly Alters ICRAC

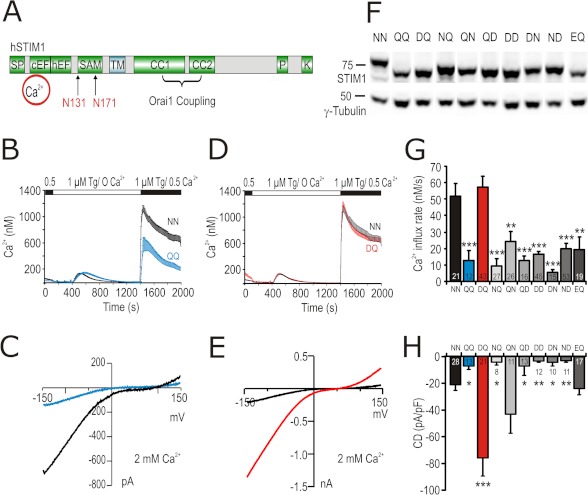

To control whether and how alterations of STIM1 and/or Orai1 N-glycosylation alter SOCE, we mutated the N-glycosylation site of Orai1 (Asn-223) and the potential luminal consensus sites for N-glycosylation in STIM1 (Asn-131 and Asn-171; Fig. 1A), which have been reported to be glycosylated in vivo (27). Mutation of the N-glycosylation site of Orai1 N223A did not lead to a significant change in current density (CD) when co-expressed with STIM1 in HEK293 cells (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). On the other hand, both Ca2+ influx and CD of the double mutant N131Q/N171Q (STIM1 QQ) were significantly smaller than wild type (STIM WT) (Fig. 1, B and C), consistent with work by Csutora et al. (28).

FIGURE 1.

Mutations in STIM1 N-glycosylation sites modulate ICRAC. A, schematic representation of structural domains in STIM1 protein showing the two N-glycosylation sites (Asn-131 and Asn-171) within the luminal EF-SAM domain. SF, signal peptide; cEF, canonical EF-hand Ca2+-binding region; hEF, hidden EF-hand Ca2+-binding region; TM, transmembrane domain; CC1 and CC2, coiled-coil regions; P, proline-rich domain; K, lysine-rich domain. B, average [Ca2+]i responses before and following store depletion by the addition of 1 μm Tg and readdition of indicated [Ca2+]o (SOCE) in cells co-transfected with Orai1 and STIM1 WT (NN, black trace) or STIM1 N131Q/N171Q (QQ, blue trace). C, exemplary current-voltage (I/V) plot of ICRAC from whole cell recordings in cells transfected as in B. D, SOCE of cells expressing Orai1 and STIM1 WT (NN, black trace) or STIM1 N131D/N171Q (DQ, red trace). E, exemplary (I/V) plot of ICRAC from whole cell recordings in cells transfected as in D. F, immune blot of total cell lysates from cells expressing Orai1 and STIM1 WT or the corresponding mutant indicated above the blot. Letters stand for single amino acid codes at positions 131 and 171, respectively. G, average of Ca2+ influx rates obtained from SOCE measurements in cells transfected as in F. H, CD extracted at 110 s and −140 mV from whole cell recordings in cells transfected as in F.

Because substitution of an asparagine to a glutamine within the NX(S/T) consensus glycosylation motif does not support the secondary structure of an Asx turn, which is necessary for recognition by oligosaccharyltransferases, we mutated Asn-131 to Asp, which, while not being a substrate for oligosaccharyltransferases, still supports the secondary structure of the Asx turn (29). In contrast to the smaller currents measured with STIM1 QQ, STIM1 DQ mutants, when co-expressed with Orai1, resulted in a strong gain of function in patch clamp recordings displaying a highly significant, ∼4-fold increase in CD (Fig. 1, E and H). In Ca2+ imaging experiments, however, STIM1 DQ mutants showed little effect on the amount of Ca2+ entry in 0.5 mm [Ca2+]o (Fig. 1, D and G), likely because of saturation of Ca2+ signals, which is seen if global Ca2+ signals are approaching the micromolar range (30). Reducing [Ca2+]o uncovers the phenotype of the STIM1 DQ mutant showing an increase in both the influx rate (supplemental Fig. S1D) and the peak [Ca2+]i after Ca2+ readdition (supplemental Fig. S1E). In addition, co-expression of STIM1 DQ resulted in an increase in the basal free [Ca2+] (supplemental Fig. S1F) and decreased peak amplitude of the Tg-induced [Ca2+] release (supplemental Fig. S1G). Thus, Ca2+ entry through store-operated channels is significantly increased in the STIM1 DQ mutant, consistent with the patch clamp data in Fig. 1E. In HEK cells with no co-expression of Orai1, neither STIM1 WT nor STIM1 DQ elicited significant inward currents (CD after 110 s: STIM1 WT −0.36 ± 0.46 pA/pF and STIM1 DQ 0.16 ± 0.14 pA/pF; not significant), suggesting that HEK cells contain little endogenous Orai1. The phenotype resulting from the STIM1 DQ mutation is specific because no other tested Asn-131 and Asn-171 mutant combination was able to mimic this effect (Fig. 1, G and H), although each mutant protein is expressed and shows the expected shifts to nonglycosylated or hemi-glycosylated MW (Fig. 1F). Inclusion of a different acidic residue at position 131 (N131E/N171Q (EQ)) did not increase Ca2+ entry above STIM1 WT either (Fig. 1, G and H). Analysis of the different NN site mutants implies that it is not the lack of glycosylation per se but possibly the association with the particular structure of the STIM1 DQ mutant EF-SAM domain that is responsible for the increased current size.

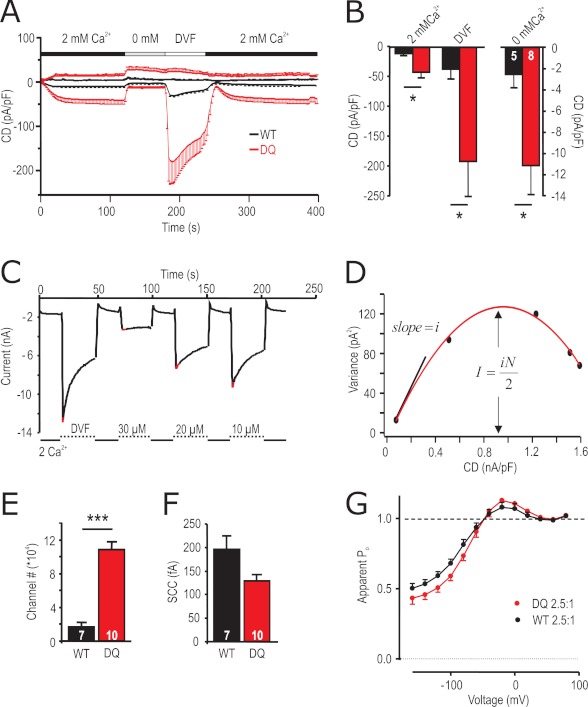

Biophysical Properties of STIM1 DQ

To investigate whether and how the strong gain of function mutant STIM1 DQ alters biophysical properties of the STIM1/Orai1 (S1/O1)-mediated currents, we measured CD in 2 mm [Ca2+]o, in nominally free [Ca2+]o and under DVF conditions (Fig. 2A). Both Ca2+ and Na+ (DVF) inward currents are significantly increased upon co-expression of STIM1 DQ (Fig. 2B). The underlying current-voltage (I/V) relationships (Fig. 1E and supplemental Fig. S2, D and E) show enhanced outward currents at positive potentials, although the traces superimpose with STIM1 WT/Orai1 currents when normalized, indicating that STIM1 DQ/Orai1 selectivity is not significantly different from the STIM1 WT/Orai1. To address the underlying mechanism of increased currents, we performed noise analysis on STIM1 WT/Orai1 and STIM1 DQ/Orai1 channel complexes. Currents were recorded under DVF conditions and after the addition of different μm amounts of external Ca2+ to decrease Po (23). Current variance was determined at the maximal current upon switching to DVF (± μm Ca2+) bath solution (Fig. 2C; see “Experimental Procedures” for detail) and plotted as a function of CD (Fig. 2D). The data were fitted by a parabolic function, and analyses of the initial slope and of the peak of the parabola showed that co-expression of STIM1 DQ resulted in a ∼ 6-fold increase in the number of active channels, whereas the single channel currents were slightly, but not significantly, smaller (Fig. 2, E and F). Open probabilities corresponding to the maximal measured CD derived from the x intercepts (Po = 1; Fig. 2D) were ∼0.75 for STIM1 WT and ∼0.78 for STIM1 DQ. To compare Ca2+-dependent inactivation and potentiation of ICRAC mediated by STIM1 WT/Orai1 and STIM1 DQ/Orai1 over the entire voltage range, we constructed apparent Po curves from normalized tail currents at −100 mV as previously described (31, 32). Transfected with similar S1/O1 DNA ratios, STIM1 WT and STIM1 DQ currents showed both potentiation (points above dashed line corresponding to the apparent Po at 80 mV, set to unity) and inactivation (points below dashed line) in 10 mm [Ca2+]o (Fig. 2G). Although the level of potentiation was the same, inactivation was slightly more pronounced for STIM1 DQ current, compared with STIM1 WT. Thus, the increased macroscopic CD with co-expression of STIM1 DQ arises from an increased number of active channels.

FIGURE 2.

Biophysical properties of STIM1 DQ-mediated Orai1 currents. A, average CD over time recorded from cells expressing Orai1 and STIM1 WT (black) or STIM1 DQ (red) extracted at +80 and −140 mV. Solution changes are indicated. B, averaged maximal inward CD for currents recorded in A in the different indicated external solutions. C, for noise analysis, currents were extracted at −120 mV in 2 mm [Ca2+] bath or in either DVF or in Mg2+-free bath with the indicated added [Ca2+]. D, current variance was extracted at indicated (red) time points in C and plotted against the CD. The red line indicates the fit using a parabolic function. E, number of channels as extracted from the maximum of the fit in D. F, single channel current (SCC) as extracted from the initial slope indicated in D. G, apparent measured open probability (Po) of Orai1 channels as a function of the applied voltage. The cells were held at 0 mV in a 2 mm Ca2+-containing solution and steps of 20 mV were applied from −160 to +80 mV over 100 ms followed by a step voltage to −100 mV. Boltzman equation was used to normalize the maximum tail current after each voltage step (see “Experimental Procedures”).

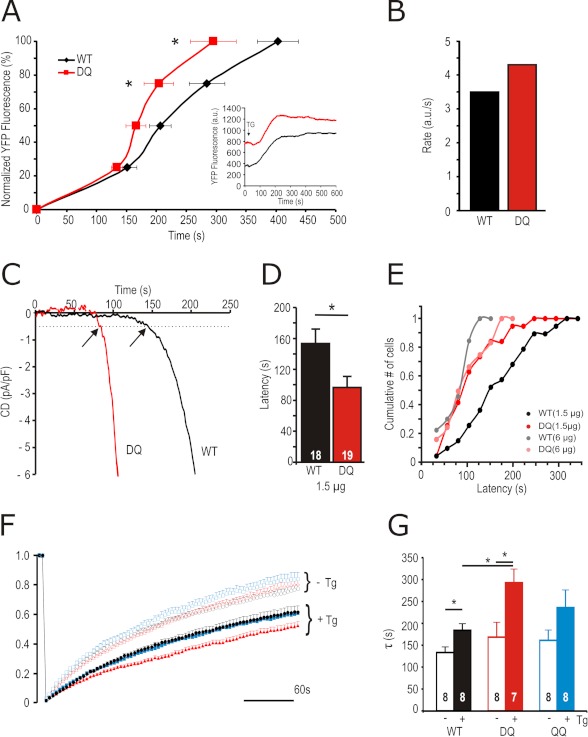

STIM1 DQ Shows Increased Rates of Translocation, Decreased Latencies with Little Change in Diffusion Parameters

To further investigate how an approximately equally expressed STIM1 mutant results in an increased number of active Orai1 channels, we investigated cluster formation rates of YFP-tagged STIM1 WT or STIM1 DQ and Orai1-RFP at a molar DNA transfection ratio of 2.5 S1/O1 by TIRF microscopy. Increases in YFP-STIM1 fluorescence at ER-PM junctions were recorded after store depletion with Tg and normalized to the maximum. Fig. 3A shows that STIM1 DQ reaches maximal fluorescence values significantly earlier than STIM1 WT. The inset plots fluorescence at a calibrated field depth of 110 nm versus time and shows that a higher amount of STIM1 DQ is already present close to the PM, as can also be seen by surface biotinylation experiments (see below). When fitted with a Hill function, STIM1 DQ shows an increased rate of clustering when compared with wild type (Fig. 3B). Congruent to the increased rate of cluster formation seen in TIRF, co-expression of STIM1 DQ mutants with Orai1 resulted in decreased latency of current activation when recorded in conditions of passive store depletion (Fig. 3, C and D). This decrease in latency can also be achieved by increasing the amount of transfected STIM1 WT DNA (6 versus 1.5 μg), whereas increasing the amount of transfected STIM1 DQ DNA does not lead to a further shift in the cumulative latencies histogram (Fig. 3E). Using a combined TIRF-FRET approach where FRET was analyzed after cluster formation, we were unable to detect differences in the interaction between STIM1 DQ and Orai1 (nFRET STIM1 WT-RFP with Orai1-GFP: 0.3 ± 0.025, n = 93 clusters, 10 cells; STIM1 DQ-RFP with Orai1-GFP: 0.299 ± 0.03, n = 88 clusters, 10 cells) or in the interaction between STIM1 WT and STIM1 DQ (nFRET WT-WT: 0.217 ± 0.03, n = 60 clusters, 9 cells, nFRET DQ-DQ: 0.200 ± 0.02, n = 59 clusters, 10 cells). This suggests that neither does STIM1 DQ interact more tightly with Orai1, nor do STIM1 DQ molecules homomultimerize more strongly than STIM1 WT. To investigate whether the increased rate of cluster formation is due to an increased diffusion of STIM1 DQ monomers or oligomers, we performed FRAP experiments.

FIGURE 3.

STIM1 DQ shows faster translocation to PM, activation kinetics, and altered diffusion following stimulation. A, traces of normalized (% of maximum) YFP fluorescence at the TIRF plane over time in cells expressing YFP-STIM1 WT (black) or STIM1 DQ (red) and Orai1-RFP. The inset shows the absolute change in fluorescence over time. B, rate of increase of YFP-fluorescence in cells measured in A, as calculated from fitting the averaged traces with a Hill function. C, exemplary traces showing kinetics of current development initiated by passive depletion in cells expressing Orai1 and STIM1 WT (black) or STIM1 DQ (red). The arrows indicate latencies defined as the time point when current size reaches 0.5 pA/pF. D, average latencies of STIM1 WT (black) and STIM1 DQ (red) measured in C. E, cumulative number of cells activated within time segments of 25 s obtained from recordings from cells transfected as in C or with 6 μg of STIM1 WT (gray) or STIM1 DQ (pink). F, traces showing YFP-STIM1 fluorescence recovery after photobleaching over time in cells expressing YFP-STIM1 WT (black circles), STIM1 DQ (red triangles), or STIM1 QQ (blue squares) with (closed) or without (open) pretreatment with Tg (see “Experimental Procedures” for analysis). G, average time constants (τ) of YFP fluorescence recovery from cells measured in F.

Fig. 3F shows the time course of recovery of bleached YFP-STIM1 WT in unstimulated or Tg-treated cells. In the absence of Tg, neither STIM1 DQ nor STIM1 QQ show differences in the time constants of recovery (Fig. 3G), indicating that basal diffusion is not affected. With Tg pretreatment, recovery is slowed because of diffusion of larger oligomers. Here, STIM1 DQ shows a small but significant (1.6-fold) prolongation of the time constant of the oligomer diffusion process (Fig. 3, F and G). Together these results point to the fact that the increased current densities recorded with STIM1 DQ may be due to enhanced kinetics of activation and not because of a change in the STIM1-Orai1 interaction.

STIM1 DQ Mutants Lead to a Prominent Loss of Orai1 Protein

To assess whether this increased number of active channels is paralleled by increased Orai1 or STIM1 protein expression, we performed Western blot analysis. Levels of STIM1 protein were on average not significantly altered when STIM1 WT, STIM1 DQ, or STIM1 QQ was co-expressed with Orai1 (see also Fig. 1F). Surprisingly, co-expression of STIM1 DQ led to a significant decrease in the amount of Orai1 protein in total cell lysates (Fig. 4A), which was not detected when STIM1 QQ was co-expressed, nor when any of the other investigated STIM1 mutants were co-expressed (supplemental Fig. S2C). Fig. 4A (right panel) shows average STIM1:Orai1 protein ratios normalized to the STIM1 WT:Orai1 ratio from nine independent experiments. Whereas co-expression of STIM1 DQ leads to an ∼3-fold increase in the STIM1:Orai1 protein ratio, co-expression of STIM1 QQ even leads to a small decrease in protein ratio (Fig. 4A). To investigate whether Orai1 protein is also decreased at the PM, we used both HA-tagged STIM1 and HA-tagged Orai1 constructs and performed biotinylation experiments to enrich PM resident proteins or PM resident-associated proteins. Fig. 4B shows that in the absence of streptavidin (SA) beads (−) total Orai1 protein is decreased upon co-expression of STIM1 DQ. In the SA retained fraction (+), a small amount of total STIM1 is bound (1.5% of total protein for wild type and 6% for STIM1 DQ; 0.55% and 0.8% after stringent urea wash; blot not shown). As expected, Orai1 is more abundant at the PM with ∼40% of total Orai1 retained by SA (STIM1 WT). The amount of PM-localized (SA-retained) Orai1 is also significantly reduced upon co-expression of STIM1 DQ, where this fraction now represents only ∼10% of its total input. By normalizing the amount of total STIM1 dimers to Orai1 tetramers in the PM, we find an overall ∼4-fold increase in the number of STIM1 dimers available for each Orai1 tetramer (Fig. 4B, right panel). An increased STIM1:Orai1 ratio is likely to result in a larger fraction of fully functional channels on the plasma membrane and a significant reduction in the number of silent channels formed by Orai1 tetramers with just one or two STIM1 dimers bound (16), thus possibly explaining the increased CD seen with STIM1 DQ. To also test ratio effects in a more native system, we investigated SOCE of Jurkat T cells after down-regulating Orai1 using siRNA or by recording from stably Orai1 overexpressing Jurkat T cells. Supplemental Fig. S3 shows that down-regulation and up-regulation of Orai1 reduce Ca2+ influx, confirming that a change in STIM1:Orai1 ratio indeed influences SOCE.

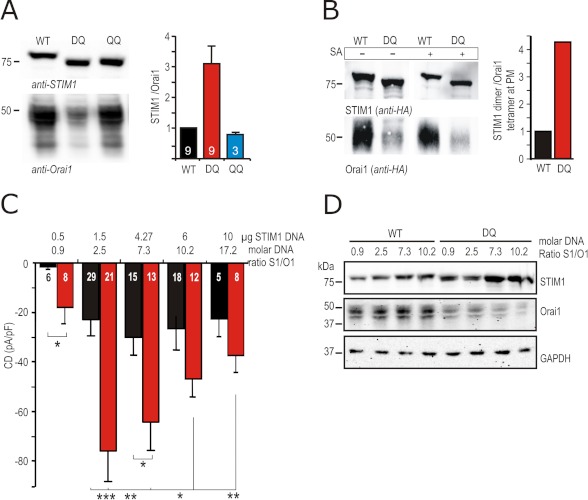

FIGURE 4.

STIM1 DQ mutant down-regulates Orai1 protein and expression of different STIM1:Orai1 DNA ratios cannot mimic the STIM1 DQ phenotype. A, left panel, immune blot of lysates of cells expressing Orai1 and STIM1 WT/DQ/QQ. Detection with anti-STIM1 or anti-Orai1 antibodies. The right panel represents the quantification of STIM1 to Orai1 protein ratios obtained from several experiments, each normalized to the WT ratio of the corresponding experiment. B, left panel, immune blot of surface expressed (biotinylated) proteins in HEK cells expressing HA-tagged Orai1 and STIM1 WT or STIM1 DQ. 50 μg of protein (5% of total) was loaded in lanes 1 and 2; lanes 3 and 4 show the entire SA-retained fraction. Detection was done with anti-HA antibody. The quantification shown in the right panel was done as follows: (total input STIM1 a.u./2)/(SA retained Orai1 a.u./4). The ratio of STIM1 DQ was normalized to WT. C, CD measured and extracted as in Fig. 1H from cells transfected with 0.5 μg of Orai1 and different DNA amounts of STIM1 (μg of STIM1) WT (black) or STIM1 DQ (red) at molar ratios shown above the bar graphs. D, immune blot of lysates of cells transfected as in C; detection with anti-STIM1, anti-Orai1, and anti-GAPDH antibodies.

Altered STIM1:Orai1 Stoichiometry Alone Does Not Mimic STIM1 DQ Mutants

To test whether STIM1 DQ leads to an increase in CD solely by altering the ratio of STIM1 to Orai1, we transfected increasing amounts of STIM1 WT DNA or decreased amounts of Orai1 DNA and measured maximal IP3-induced CD (Fig. 4C and supplemental Fig. S2A). With the assumption that the molar DNA ratios approximate translated protein ratios, we varied the amount of transfected DNA of both STIM1 WT and STIM1 DQ while keeping Orai1 constant at 0.5 μg (0.1 pmol) transfected DNA. An S1/O1 suboptimal molar DNA ratio of 0.9 resulted in very small currents, whereas ratios of 2.5 or above reached saturated CDs (Fig. 4C). Within the tested DNA ratios, co-transfection at a suboptimal molar ratio of 0.9 already leads to a significant CD increase in STIM1 DQ-expressing cells. Increasing the molar ratio to 2.5 increases STIM1 WT/Orai1 CD to approximately those reached by STIM1 DQ/Orai1 at 0.9; however, STIM1 DQ peaks to a now 3–4-fold increased CD of −76 ± 12 pA/pF. Increasing STIM1 DQ above 1.5 μg (0.28 pmol) leads to a decreasing CDs, whereas STIM1 WT-mediated currents show very little decrease. At very high STIM1 concentrations (6 μg, 1.1 pmol) or above (10 μg, 1.9 pmol), the differences between STIM1 WT and mutant CDs become nonsignificant, although protein ratio differences still exist (see supplemental Fig. S2B). IP3-induced STIM1 WT-mediated CDs were unable to reach those measured with the 2.5 molar ratio of STIM1 DQ. Even at a very small molar DNA ratio of 0.3 S1/O1 co-expression of STIM1 DQ resulted in a significant ∼4-fold increase in CD (−5.4 ± 1.6 pA/pF STIM1 WT versus −19.6 ± 4.3 pA/pF for STIM1 DQ; p < 0.01).

Corresponding protein ratios to Fig. 4C were analyzed 24 h after transfection. Fig. 4D shows an exemplary Western blot of STIM1 and Orai1 protein transfected at different molar DNA ratios. Orai1 protein appears as double bands because of different complex glycosylation states, similar to Orai1 of Jurkat T cells (tunicamycin- and Peptide: N-glycosidase F (PNGaseF)-sensitive, endoglycosidase H-resistant (EndoH); see supplemental Fig. S1C). Even at low amounts of transfected STIM1 DNA, co-transfection of STIM1 DQ leads to a decrease in the amount of Orai1 protein, whereas GAPDH is not affected. Averaging the STIM1:Orai1 ratios of several experiments (supplemental Fig. S2B), it becomes apparent that STIM1 DQ leads to an increased STIM1:Orai1 ratio with all transfected DNA ratios. The inability of different STIM1 WT to Orai1 ratios to produce similarly enhanced current densities even at corresponding protein ratios (compare protein ratios and CD of STIM1 WT at a molar DNA ratio of 7.3 with STIM1 DQ at a molar DNA ratio of 2.5, or of STIM1 DQ at 0.9 with STIM1 WT at 2.5). Supplemental Fig. S2B suggests that the altered kinetic parameters (Fig. 3) of STIM1 DQ are an important determinant of its strong gain of function phenotype.

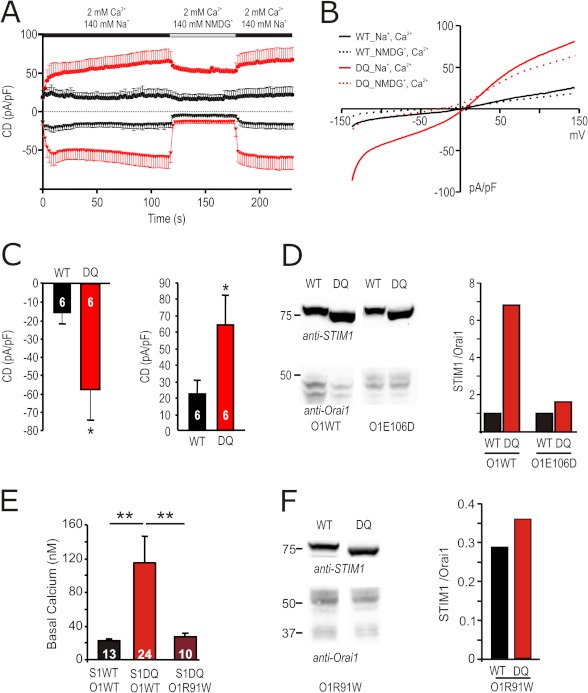

To separate effects on kinetics from effects on stoichiometry, as well as to address a possible mechanism for the STIM1 DQ-induced reduction in Orai1 protein, we co-transfected STIM1 WT or STIM1 DQ with the pore mutant of Orai1 E106D (33). Orai1 E106D mutants show IP3-induced currents, but because of mutation of the selectivity filter, they lack Ca2+ selectivity. Fig. 5A shows that STIM1 DQ also amplifies Orai1 E106D currents. Replacement of Na+ in the bath with NMDG abolished inward currents, confirming that those are carried by Na+. Fig. 5B shows the corresponding I/V relationships. At a molar DNA transfection ratio of 2.5, co-expression of STIM1 DQ also shows a ∼4-fold significant increase of the inward CD (Fig. 5, A and C). However, Orai1 E106 protein levels are not reduced upon co-expression of STIM1 DQ (Fig. 5D) demonstrating that 1) the phenotype of STIM1 DQ does not solely depend on changes in the STIM1:Orai1 stoichiometry and 2) the reduction of Orai1 protein levels by STIM1 DQ requires Ca2+ influx through Orai1. To confirm that the increased basal [Ca2+]i seen upon co-expression of STIM1 DQ (see also supplemental Fig. S1F) is the underlying cause of decreased Orai1 protein, we also co-expressed STIM1 DQ with the nonfunctional Orai1 R91W. This mutant neither increased basal [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5E) nor changed the amount of Orai1 seen on Western blots (Fig. 5F). We have also used a stable Orai1-expressing HEK cell line (HEKO1) and transiently transfected either STIM1 WT or STIM1 DQ. STIM1 DQ again induced a ∼4-fold increase in current density (supplemental Fig. S2F) with little change in protein ratio (supplemental Fig. S2G), confirming that the phenotype can be detected independent of a major change in protein ratio.

FIGURE 5.

The Orai1 pore mutant E106D is amplified by, but largely protected against, STIM1 DQ-induced degradation. A, traces showing average CD over time recorded from cells transfected with 0.5 μg of Orai1 E106D and 1.5 μg of STIM1 WT (black) or STIM1 DQ (red) extracted at +120 and −140 mV. External solution was changed as shown in the bar above the traces. B, corresponding I/V plots from cells measured in A, extracted in Na+-containing (110 s, solid lines) and NMDG-containing (140 s, dotted lines) solution. C, CD in cells recorded in A, extracted in the Na+-containing solution after 110 s at −140 mV (left panel) or +120 mV (right panel). D, immune blot of lysates of cells transfected as in A or with 0.5 μg of Orai1WT together with 1.5 μg of STIM1WT or STIM1 DQ (left panel). Detection was done with the indicated antibodies, and STIM1/Orai1 protein ratios are quantified in the right panel. E, basal [Ca2+]i in cells transfected either with 0.5 μg of Orai1 WT or Orai1 R91W and 1.5 μg of STIM1 WT or STIM1 DQ as indicated below ([Ca2+]o 2 mm). F, immune blot of lysates of cells transfected as in E. Detection was done with the indicated antibodies, and STIM1/Orai1 protein ratios are quantified in the right panel.

A Diffusion Trap Model Can Describe ICRAC Activation by STIM1 WT and Mutants

To further delineate relative contributions of altered kinetics and/or changes in stoichiometry of Orai1 and STIM1 and to aid analysis of many more mutants, we assumed a Gillespie-Monte Carlo algorithm to simulate a two-dimensional diffusion reaction system describing a local hot spot (ER-PM Junction) of interaction (Fig. 6A). Based on the reaction scheme shown in Fig. 6B and parameters shown in Table 1 and assuming an optimal binding stoichiometry of eight STIM1s per tetramer of Orai1 (for details see “Experimental Procedures” and Ref. 16), the model (Fig. 6C, triangles) predicts maximal ICRAC steady state currents at a total input ratio of 7.5 STIM1:Orai1 (tetramer), with declining currents at higher Orai1 concentrations (lower S1/O1 ratios). Fig. 6C shows that the measured normalized CD (black circles) of the different DNA transfection ratios of STIM1 WT correspond with the model data (triangles), whereas measured values for STIM1 DQ mutants (red circles), normalized to the maximal measured STIM1 WT values, show a much steeper and increased current/ratio relationship. Given the finding that STIM1 DQ mutants translocate faster, we now modeled different STIM1 mutant scenarios by assuming: 1) increased STIM1 oligomerization rate (k1, mutant A), 2) increased STIM1-Orai1 interaction (mutant B), 3) decreased negative cooperativity of ON rates (mutant C), or 4) increased STIM1 dimer diffusion (mutant D). Fig. 6D plots the simulated currents versus the STIM1/Orai1 ratios of these mutants compared with STIM1 WT, showing that a sole increased STIM1-Orai1 interaction (mutant B) or decrease in negative cooperativity (mutant C) would not sufficiently describe the measured STIM1 DQ mutant, whereas increased oligomerization (mutant A) or increased dimer diffusion (mutant D) is able to mimic the phenotype of the STIM1 DQ mutant. To better demonstrate why changes in the mutant parameters affect current size, Fig. 6E shows how the overall WT channel ensemble is a sum of channels with different occupancy states. If, as shown in Fig. 6F, a mutant increases the relative contribution of OS4 (high conducting), current size will increase despite similar numbers of total Orai1 or STIM1 proteins.

Given the fact that unstimulated STIM1 DQ did not show altered recovery rates in FRAP experiments (Fig. 3, F and G) and that Tg-induced dimer/oligomer recovery showed decreased recovery time constants for STIM1 DQ, our data indicate that an increased rate of oligomerization (increased k1: mutant A; see Fig. 6, D and F), in conjunction with a shift in STIM1:Orai1 stoichiometry underlies the STIM1 DQ mutant phenotype.

DISCUSSION

We set out to investigate a potential role of N-linked glycosylation for the physiological function of STIM1. Both glycosylation sites are localized within the SAM domain, with the first site (Asn-131) immediately prior to the initial SAM domain α helix (α6) and the second site (Asn-171) localized at the beginning of the short internal SAM domain α9 helix (34). Although mutation of a conserved tryptophan adjacent to Asn-131, namely W132R, had little effect on the quaternary structure and oligomerization of the EF SAM domain, mutation of T172R, adjacent to Asn-171, led to persistent EF-SAM aggregation (34). In contrast to earlier work, which showed either reduced STIM1 function upon mutation of the consensus glycosylation site asparagines to glutamines N131Q/N171Q (28) or an unaltered endogenous SOCE (35), we were able to show that prevention of glycosylation does not reduce function per se and that a particular mutant combination, namely N131D/N171Q (DQ), instead created a strong gain of function mutant. In comparison with the α9 helix destabilizing mutation T172R, which leads to constitutive activation combined with Tg insensitivity of Mn2+ quench rates (34), STIM1 DQ mutants display Tg sensitivity, do not show constitutive currents in patch clamp recordings, and thus do not lead to permanently activated Orai1 channels. However, Tg-induced store depletion in 0 Ca2+ results in more rapid cluster formation consistent with decreased latencies of passively depleted store-operated currents (Fig. 3, C and D). Increased localization of STIM1 DQ near the PM (Fig. 3A, inset), together with higher basal [Ca2+]i (Fig. 5E and supplemental Fig. S1F), suggests that a partial destabilization of the EF-SAM domain may ease the transition from the “open” (Ca2+-bound) to the “closed” (Ca2+-depleted) state of the molecule (34, 36), thereby increasing the rate of oligomerization k1 (Fig. 6B). This may lead to transient and random openings of co-expressed Orai1 channels, triggering their Ca2+-dependent degradation. A functional but non-Ca2+-conducting Orai1 mutant (Orai1 E106D), as well as the nonfunctional R91W mutant, which can still interact with STIM1, is largely protected from protein degradation (Fig. 5, D and F), resembling the effects seen with a GOF mutation in TRPML3 (37). Quantitative RT-PCR data showed no difference in the Orai1 transcript levels upon co-expression of STIM1 WT or STIM1 DQ, indicating that regulation of Orai1 protein is a post-transcriptional effect. The STIM1 DQ-induced reduction of Orai1 protein could enable a shift toward an optimized STIM1:Orai1 stoichiometry, which would have a large impact on current size at suboptimal STIM1:Orai1 ratios, yielding too many low conducting channel states. However, we were unable to titrate STIM1 WT and Orai1 levels such that IP3-induced CD of STIM1 DQ co-expression could be mimicked. Although increasing the amount of transfected STIM1 WT can lead to comparable STIM1:Orai1 protein ratios (compare WT at 7.3 with STIM1 DQ at 2.5 ratio; supplemental Fig. S2B), this does not lead to similarly increased CD (Fig. 4C), pointing to an additional effect of STIM1 DQ. Analyses of Orai1 E106D mutants or of the Orai1 stable cell line, which do not show reduced protein ratios upon co-expression of STIM1 DQ (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S2, F and G), further proves that STIM1 DQ is able to enhance Orai1 currents by an alternative mechanism. The enhanced translocation rate of STIM1 DQ toward the PM suggests enhanced oligomerization rates or possibly increased STIM1 dimer diffusion and fits well with previous data of other mutants that destabilize the EF SAM domain (36). Indeed, when we applied different predictions about oligomerization and altered diffusion rates into a diffusion trap model of STIM1-Orai1 interaction, we were able to simulate increases in current size by an enhanced STIM1 oligomerization rate or diffusion (mutant A, D), which will be due to an increased relative contribution of channels in the OS4 occupied state (one Orai1 tetramer with four STIM1 dimers bound; see Fig. 6B). FRAP analysis (Fig. 3, F and G) indicates that unstimulated recovery rates are similar for STIM1 WT and STIM1 DQ, whereas oligomerized STIM1 DQ molecules show decreased FRAP recovery rates, suggesting larger STIM1 DQ complexes. The increase in the number of channels in STIM1 DQ as determined by noise analyses (Fig. 2E) can thus be best explained by enhanced STIM1 DQ oligomerization with a possible minor contribution of a stoichiometric shift. In addition to the ratio aspect introduced in the model proposed by Hoover and Lewis (16), our model accounts for local aspects with respect to diffusion properties of STIM1 and Orai1 and is therefore also able to include time-dependent components of ICRAC. Regulation of Orai1 protein stability by its interacting partner STIM1 represents an additional novel Ca2+-dependent mechanism, which may lead to increased or decreased ICRAC depending on the STIM1:Orai1 ratio, and thus has broad implications for many cell types.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Peter Lipp and Lars Kaestner for the use of the confocal microscope; Dr. Markus Hoth and members of the lab for suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript; and Bettina Strauss, Andrea Armbrüster, and Gertrud Schwär for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB894, Project A2 (to B. A. N. and C. P.), NI671/3-1 to B. A. N., Emmy Noether Program 1478/5-1 (to C. P.), and funds from HOMFORexcellent (to D. A.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- STIM

- stromal interaction molecule

- SOCE

- store-operated calcium entry

- CRAC

- calcium release-activated calcium

- Tg

- thapsigargin

- CD

- current density

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- PM

- plasma membrane

- TIRF

- Total Internal Reflection Fluorescent

- FRAP

- fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- SAM

- sterile α motif

- NMDG

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

- DVF

- divalent free

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein

- SA

- streptavidin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Rao A. (2010) Molecular basis of calcium signaling in lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 491–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maul-Pavicic A., Chiang S. C., Rensing-Ehl A., Jessen B., Fauriat C., Wood S. M., Sjöqvist S., Hufnagel M., Schulze I., Bass T., Schamel W. W., Fuchs S., Pircher H., McCarl C. A., Mikoshiba K., Schwarz K., Feske S., Bryceson Y. T., Ehl S. (2011) ORAI1-mediated calcium influx is required for human cytotoxic lymphocyte degranulation and target cell lysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3324–3329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qu B., Al-Ansary D., Kummerow C., Hoth M., Schwarz E. C. (2011) ORAI-mediated calcium influx in T cell proliferation, apoptosis and tolerance. Cell Calcium 50, 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S. H., Tanasa B., Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Daly M., Rao A. (2006) A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441, 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Oh-Hora M., Hogan P. G., Lamperti E. D., Yamashita M., Gelinas C., Neems D. S., Sasaki Y., Feske S., Prakriya M., Rajewsky K., Rao A. (2008) Hair loss and defective T- and B-cell function in mice lacking ORAI1. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 5209–5222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vig M., DeHaven W. I., Bird G. S., Billingsley J. M., Wang H., Rao P. E., Hutchings A. B., Jouvin M. H., Putney J. W., Kinet J. P. (2008) Defective mast cell effector functions in mice lacking the CRACM1 pore subunit of store-operated calcium release-activated calcium channels. Nat. Immunol. 9, 89–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oh-Hora M., Yamashita M., Hogan P. G., Sharma S., Lamperti E., Chung W., Prakriya M., Feske S., Rao A. (2008) Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 9, 432–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muik M., Fahrner M., Derler I., Schindl R., Bergsmann J., Frischauf I., Groschner K., Romanin C. (2009) A cytosolic homomerization and a modulatory domain within STIM1 C terminus determine coupling to ORAI1 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8421–8426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park C. Y., Hoover P. J., Mullins F. M., Bachhawat P., Covington E. D., Raunser S., Walz T., Garcia K. C., Dolmetsch R. E., Lewis R. S. (2009) STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell 136, 876–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yuan J. P., Zeng W., Dorwart M. R., Choi Y. J., Worley P. F., Muallem S. (2009) SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 337–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liou J., Fivaz M., Inoue T., Meyer T. (2007) Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9301–9306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luik R. M., Wu M. M., Buchanan J., Lewis R. S. (2006) The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry. Local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J. Cell Biol. 174, 815–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lioudyno M. I., Kozak J. A., Penna A., Safrina O., Zhang S. L., Sen D., Roos J., Stauderman K. A., Cahalan M. D. (2008) Orai1 and STIM1 move to the immunological synapse and are up-regulated during T cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2011–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quintana A., Pasche M., Junker C., Al-Ansary D., Rieger H., Kummerow C., Nuñez L., Villalobos C., Meraner P., Becherer U., Rettig J., Niemeyer B. A., Hoth M. (2011) Calcium microdomains at the immunological synapse. How ORAI channels, mitochondria and calcium pumps generate local calcium signals for efficient T-cell activation. EMBO J. 30, 3895–3912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li Z., Liu L., Deng Y., Ji W., Du W., Xu P., Chen L., Xu T. (2011) Graded activation of CRAC channel by binding of different numbers of STIM1 to Orai1 subunits. Cell Res. 21, 305–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoover P. J., Lewis R. S. (2011) Stoichiometric requirements for trapping and gating of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels by stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13299–13304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Varga-Szabo D., Braun A., Kleinschnitz C., Bender M., Pleines I., Pham M., Renné T., Stoll G., Nieswandt B. (2008) The calcium sensor STIM1 is an essential mediator of arterial thrombosis and ischemic brain infarction. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1583–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feske S. (2011) Immunodeficiency due to defects in store-operated calcium entry. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1238, 74–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marth J. D., Grewal P. K. (2008) Mammalian glycosylation in immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 874–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sperandio M., Gleissner C. A., Ley K. (2009) Glycosylation in immune cell trafficking. Immunol. Rev. 230, 97–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Feske S., Cruz-Guilloty F., Oh-hora M., Neems D. S., Hogan P. G., Rao A. (2007) Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16232–16243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stanisz H., Stark A., Kilch T., Schwarz E. C., Müller C. S., Peinelt C., Hoth M., Niemeyer B. A., Vogt T., Bogeski I. (2012) ORAI1 Ca2+ channels control endothelin-1-induced mitogenesis and melanogenesis in primary human melanocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 1443–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prakriya M., Lewis R. S. (2006) Regulation of CRAC channel activity by recruitment of silent channels to a high open-probability gating mode. J. Gen. Physiol. 128, 373–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gillespie D. T. (1976) A general method for numerically simulating the stochastic time evolution of coupled chemical reactions. J. Comput. Phys. 22, 403–434 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gibson M. A., Bruck J. (2000) Efficient exact stochastic simulation of chemical systems with many species and many channels. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 1876–1889 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Williams R. T., Senior P. V., Van Stekelenburg L., Layton J. E., Smith P. J., Dziadek M. A. (2002) Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), a transmembrane protein with growth suppressor activity, contains an extracellular SAM domain modified by N-linked glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1596, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Csutora P., Peter K., Kilic H., Park K. M., Zarayskiy V., Gwozdz T., Bolotina V. M. (2008) Novel role for STIM1 as a trigger for calcium influx factor production. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14524–14531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Imperiali B., Hendrickson T. L. (1995) Asparagine-linked glycosylation. Specificity and function of oligosaccharyl transferase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 3, 1565–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoth M., Fanger C. M., Lewis R. S. (1997) Mitochondrial regulation of store-operated calcium signaling in T lymphocytes. J. Cell Biol. 137, 633–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scrimgeour N., Litjens T., Ma L., Barritt G. J., Rychkov G. Y. (2009) Properties of Orai1 mediated store-operated current depend on the expression levels of STIM1 and Orai1 proteins. J. Physiol. 587, 2903–2918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scrimgeour N. R., Wilson D. P., Rychkov G. Y. (2012) Glu106 in the Orai1 pore contributes to fast Ca2+-dependent inactivation and pH dependence of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) current. Biochem. J. 441, 743–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vig M., Beck A., Billingsley J. M., Lis A., Parvez S., Peinelt C., Koomoa D. L., Soboloff J., Gill D. L., Fleig A., Kinet J. P., Penner R. (2006) CRACM1 multimers form the ion-selective pore of the CRAC channel. Curr. Biol. 16, 2073–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stathopulos P. B., Zheng L., Li G. Y., Plevin M. J., Ikura M. (2008) Structural and mechanistic insights into STIM1-mediated initiation of store-operated calcium entry. Cell 135, 110–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mignen O., Thompson J. L., Shuttleworth T. J. (2007) STIM1 regulates Ca2+ entry via arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels without store depletion or translocation to the plasma membrane. J. Physiol. 579, 703–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zheng L., Stathopulos P. B., Schindl R., Li G. Y., Romanin C., Ikura M. (2011) Auto-inhibitory role of the EF-SAM domain of STIM proteins in store-operated calcium entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1337–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim H. J., Li Q., Tjon-Kon-Sang S., So I., Kiselyov K., Soyombo A. A., Muallem S. (2008) A novel mode of TRPML3 regulation by extracytosolic pH absent in the varitint-waddler phenotype. EMBO J. 27, 1197–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Rheenen J., Langeslag M., Jalink K. (2004) Biophys. J. 86, 2517–2529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]