Abstract

Objective

To estimate 12-month satisfaction and continuation rates of intrauterine device (IUD) and implant users enrolled in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and compare these measures to women using the oral contraceptive pills (OCPs).

Methods

We analyzed 12-month data from the first 5,087 participants enrolled in a prospective cohort study of women in the St. Louis region offered contraception at no cost for 3 years. The primary purpose of CHOICE is to promote the use of long-acting reversible contraception (IUDs and implants) and to reduce unintended pregnancies in our region. This analysis includes participants who received their baseline contraceptive method within 3 months of enrollment and who reached the 12-month follow-up phone survey time point (N=4,167).

Results

Sixty-eight percent of our participants chose a long-acting reversible contraception method (45% levonorgestrel intrauterine system, 10% copper IUD, and 13% subdermal implant), while 23% chose combined hormonal methods (11% OCPs, 10% vaginal ring, and 2% transdermal patch), and 8% chose depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Long-acting reversible contraception users had higher 12-month continuation rates (86%) than OCP users (55%). The two IUDs had the highest 12-month continuation rates: levonorgestrel intrauterine system (88%) and copper IUD (84%). Women using the implant also had very high rates of continuation at 1 year (83%). Satisfaction mirrored continuation: over 80% of users were satisfied with the IUD compared to 54% satisfied with OCPs.

Conclusion

IUDs and the subdermal implant have the highest rates of satisfaction and 12-month continuation. Given that long-acting reversible contraception methods have the highest contraceptive efficacy, these methods should be the first-line contraceptive methods offered to patients.

INTRODUCTION

Satisfaction and continuation rates of common forms of contraception in the United States are disappointing. According to the most recent National Survey of Family Growth, 28% of women taking contraceptives in the U.S. use the oral contraceptive pill (OCP).1 However, continuation rates for OCs are reported to be as low as 29% at 6 months.2 Rosenberg and Waugh found that women who discontinue OCs often do not begin a new contraceptive method or changed to less effective contraceptive options.3 The 6-month continuation rate for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) was recently found to be 36–48%,4 and studies cite a 12-month continuation rate as low as 23–28%.5,6 Contraceptive discontinuation will often result in unintended pregnancy.

Despite their proven safety, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness, long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (LARC; intrauterine device (IUDs) and the subdermal implant) are not widely used in the U.S. In fact, only 5.5% of women taking contraceptives between the ages of 15 - 44 years use the intrauterine device (IUD).1 Reasons for lack of use of these highly effective reversible methods include: women’s and provider’s knowledge of and attitudes toward the methods; practice patterns among providers; myths and misconceptions regarding the side effects of these methods; high initial cost, and, provider biases.7–11 LARC methods, however, are believed by many experts to have the highest continuation rates and high levels of satisfaction among all methods of contraception. However, longitudinal data assessing 12-month continuation rates and satisfaction of U.S. women using LARC methods are lacking.

The purpose of this analysis is to estimate the 12-month continuation and satisfaction rates of LARC method users in women enrolled in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, and compare these measures to women using the OCs: the most common form of reversible contraception used in the U.S. Our hypothesis was that women using LARC methods would have higher levels of satisfaction and higher continuation rates than women using OCs.

METHODS

The methodologic details of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project (CHOICE) have been previously described.12 A brief description of the project and the analytic approach for this report are described below. The CHOICE protocol was approved by the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office prior to the initiation of recruitment.

CHOICE is an observational cohort study developed to promote the use of LARC methods (specifically the subdermal implant and the intrauterine device) in the St. Louis region. Our primary objective is to provide no-cost contraception to a large number of women in our region in an effort to reduce unplanned pregnancies. To accomplish these objectives, we sought to remove two major barriers to LARC use: financial obstacles and lack of patient awareness of LARC method safety and efficacy. By increasing the acceptance and use of LARC, CHOICE seeks to reduce unintended pregnancy at the population level in our region.

CHOICE is a convenience sample of women in the St. Louis City and County. Participants are recruited from clinics serving women at high risk for unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as well as from the local community including college students, graduate students, and personnel affiliated with Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Recruitment occurs via general awareness about the CHOICE Project through medical providers, newspaper reports, study flyers, and word of mouth.

Inclusion criteria for CHOICE include: 1) age 14–45 years; 2) not currently using a contraceptive method or willing to start a new reversible contraceptive method (may have used the chosen method previously, but not their current method of contraception); 3) no desire to conceive for at least 12 months; 4) sexually active with a male partner (or an intent to be active in the next 6 months); 5) reside in or seek clinical services in designated recruitment sites in the St. Louis region; and 6) ability to consent in English or Spanish. Women were excluded if they had a hysterectomy or sterilization procedure or were unwilling to try a new method. Additional inclusion criteria for this analysis include participants who: 1) completed the 12-month follow-up survey or provided information that they discontinued their contraceptive method prior to the survey; and 2) received and initiated their baseline chosen method of contraception within 3 months of enrollment.

All potential participants in the CHOICE Project are read a standardized script regarding LARC methods, regardless of whether or not they enroll in the project.12 All enrolled participants receive standardized contraceptive counseling. During counseling, all reversible contraceptive methods are presented and their associated levels of effectiveness, common side effects, risks and benefits are described so that participants can make an informed decision. Each participant is provided reversible contraception at no cost for 3 years. After a comprehensive baseline interview and screening for sexually transmitted infections (Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Trichomonas vaginalis, syphilis, and HIV), we prospectively follow all participants. We conduct phone interviews at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months post enrollment using standardized survey instruments. Participants are compensated with a $10.00 gift card for every completed follow-up survey.

In the baseline and follow-up survey instruments, we collect comprehensive information on demographic characteristics, reproductive history including contraceptive experience, sexual behavior including number and gender of sexual partners, and incident STI. The baseline survey is administered face-to-face in a private setting by trained study staff. We used the following definitions in the survey: 1) public assistance (yes): if the participant responded that she currently receives food stamps, WIC, welfare, or unemployment; and 2) unintended pregnancy (yes): responded yes to “you wanted to be pregnant later or you didn’t want to be pregnant then or any time in the future” when asked about a previous pregnancy. Research staff also collects and records clinically relevant data, including complaints, complications, side effects, method expulsions and removals, pregnancies and outcomes from any problem visits or phone calls.

At each follow-up survey, participants were asked the question “are you still using the method?” If the participant answered “yes,” they would be further asked “did you ever stop using the method?” A participant was considered a “continuer” if she reported using her baseline method at the 3, 6 and 12-month survey without any temporary stop of one month or longer. We defined a “discontinuer” as those who reported not using the baseline method at any of the survey time points or reported any temporary stop of the method for one month or longer. For participants who failed to answer these questions, our method allocation log and pharmacy refill records were checked to confirm their status. We offered IUD replacement to women who experienced an expulsion (3.5%). When the IUD was replaced, and the participant was using the same method at 12 months, we considered this a “continuer.” If the participant elected NOT to have the same IUD replaced, she was considered a “discontinuer.” Participants who were lost to follow-up were censored at their last completed survey date. Satisfaction level was evaluated on the continuers at 12-month. Satisfaction was categorized in 3 levels: “very satisfied”, “somewhat satisfied,” and “not satisfied.” All participants who discontinued their method by 12 months were considered “not satisfied.” We grouped “very satisfied” and “somewhat satisfied” together as “satisfied” in the modeling (multivariable) stage of the analysis. We calculated 12-month continuation rates and also levels of satisfaction of all contraceptive methods. Individual methods were compared to oral contraceptive pill (OC) users, since OCs are the most commonly used reversible contraceptive method in the United States.1 We also grouped participants as LARC users and users of other contraceptive (non-LARC) methods in our analysis.

To describe demographic characteristics of the study participants, frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were used for appropriate data type. To compare these baseline covariates among different method users, chi-square and Fisher exact tests were performed when appropriate for categorical variables, as well as Student t-test for continuous normally distributed variables. Normality was assessed by evaluating the histogram of continuous variables. To compare the continuation among different method users, Kaplan - Meier survival curves were constructed to estimate the continuation rates, and Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the hazard rate ratios (HRR) between methods. Proportional hazard assumptions were checked by plotting the log-log of survival probability. For the purpose of comparing the satisfaction rates among different method users, Poisson regression models with robust error variance were used to estimate relative risk and 95% confidence intervals. This analytic approach provides an unbiased estimate of the relative risk when the outcome is common (greater than 10%).13 Effect modification was checked by including an interaction term between the method and the covariate of interest in the model. Effect modification was detected if the interaction term was statistically significant at the pre-specified alpha level. Confounding was defined as a greater than 10% relative change in the association between continuation/satisfaction and method choice with or without the covariate of interest in the model. Confounders were included in the final multivariable model. All analyses were performed using STATA 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The significance level alpha was set at 0.05. We decided a priori to do an analysis of continuation rates after 5,000 participants were recruited and followed for 12 months. This sample size gave us adequate power (> 90%) to detect a two-fold increase in discontinuation with OCs compared to LARC methods.

RESULTS

Of the first 5,087 women enrolled in CHOICE between August 2007 and December 2009, 4,936 reached their 12 month time point, and 4,167 met the inclusion criteria for this analysis. There were 3,016 women (72.4%) still using their baseline method at 12 months, 996 (23.9%) who discontinued, and 155 (3.7%) who were lost to follow-up. Table 1 presents the baseline demographic and reproductive characteristics of these 4,167 participants and the first 5,087 women enrolled into CHOICE. The characteristics of the subset are similar to the cohort overall. In our analytic sample, the mean age is 25 years; 47% are African American; 34% had a high school education or less; 33% receive public assistance; and 40% have trouble paying for basic necessities. Forty-eight percent are nulliparous, 66% experienced an unintended pregnancy, and 40% had an abortion.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Analysis Sample and Total CHOICE Population

| Sample (n=4,167) | CHOICE (N=5,087) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 25.2±5.7 | 25.2±5.7 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 1,967 (47.4) | 2,443 (48.3) |

| White | 1,874 (45.2) | 2,242 (44.3) |

| Others | 307 (7.4) | 376 (7.4) |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma or less | 1,424 (34.2) | 1,820 (35.8) |

| Some college | 1,772 (42.5) | 2,142 (42.1) |

| College degree or graduate school | 969 (23.3) | 1,123 (22.1) |

| Income per month | ||

| None | 686 (16.9) | 883 (17.8) |

| $1–800 | 1,308 (32.2) | 1,606 (32.4) |

| $801–1,600 | 1,225 (30.2) | 1,473 (29.7) |

| $1,601 or more | 837 (20.6) | 990 (20.0) |

| Body mass index | ||

| Underweight | 134 (3.2) | 151 (3.0) |

| Normal | 1,664(39.9) | 2,042 (40.1) |

| Overweight | 1,059 (25.4) | 1,295 (25.5) |

| Obese | 1,310 (31.4) | 1,599 (31.4) |

| Receiving public assistance | ||

| No | 2,785 (66.8) | 3,331 (65.5) |

| Yes | 1,382 (33.2) | 1,756(34.5) |

| Trouble paying for basic expenses | ||

| No | 2,496 (59.9) | 3,021 (59.4) |

| Yes | 1,671 (40.1) | 2,066 (40.6) |

| Insurance | ||

| None | 1,802 (43.6) | 2,203 (43.7) |

| Private | 1,865 (45.1) | 2,219 (44.0) |

| Public | 466 (11.3) | 624 (12.4) |

| Gravidity | ||

| 0 | 1,184 (28.4) | 1,428 (28.1) |

| 1 | 907 (21.8) | 1,095 (21.5) |

| 2 | 757 (18.2) | 913 (17.9) |

| 3 or higher | 1,319 (31.7) | 1,651 (32.5) |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 1,985 (47.6) | 2,377 (46.7) |

| 1 | 1,026 (24.6) | 1,256 (24.7) |

| 2 | 724 (17.4) | 901 (17.7) |

| 3 or higher | 432 (10.4) | 553 (10.9) |

| Unintended pregnancies | ||

| 0 | 1,408 (33.9) | 1,718 (33.9) |

| 1 | 1,159 (27.9) | 1,397 (27.5) |

| 2 | 704 (16.9) | 849 (16.7) |

| 3 or more | 885 (21.3) | 1,111 (21.9) |

| History of abortion | ||

| No | 2,518 (60.4) | 3,115 (61.2) |

| Yes | 1,649 (39.6) | 1,972 (38.8) |

| History of STI | ||

| No | 2,534 (60.8) | 3,067 (60.3) |

| Yes | 1,633 (39.2) | 2,020 (39.7) |

| Any current STI | ||

| No | 3,905 (93.7) | 4,736 (93.1) |

| Yes | 262 (6.3) | 351 (6.9) |

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Data are mean±standard deviation or n (%).

Table 2 provides the baseline characteristics of our sample population by contraceptive method. Among women enrolled, over two-thirds (68.3%; 95% confidence interval (CI) 66.9, 69.7) chose a long-acting reversible contraceptive method: 45% chose a levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), 10% chose a copper IUD, and 13% chose the etonogestrel subdermal implant. With regard to non-LARC methods, 8% chose DMPA, and 23% chose combined hormonal methods (11% OCPs, 10% vaginal ring, and 2% transdermal patch).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics by Contraceptive Method

| LNG-IUS (n=1,890) |

Copper-IUD (n=434) |

Implant (n=522) |

DMPA (n=313) |

OCs (n=478) |

Patch (n=99) |

Ring (n=431) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 25.9±5.6 | 28.1±6.3 | 23.2±5.9 | 24.6±6.1 | 23.8±5.1 | 24.1±4.2 | 24.1±4.4 | |

| Race | [lt].001 | |||||||

| African American | 898 (45.7) | 162 (8.2) | 270 (13.7) | 227 (11.5) | 193 (9.8) | 53 (2.7) | 164 (8.3) | |

| White | 857 (45.7) | 229 (12.2) | 211 (11.3) | 66 (3.5) | 245 (13.1) | 39 (2.1) | 227 (12.1) | |

| Others | 128 (41.7) | 41 (13.4) | 38 (12.4) | 19 (6.2) | 38 (12.4) | 7 (2.3) | 36 (11.7) | |

| Education | [lt].001 | |||||||

| High school diploma or less | 613 (43.0) | 125 (8.8) | 282 (19.8) | 162 (11.4) | 131 (9.2) | 30 (2.1) | 81 (5.7) | |

| Some college | 830 (46.8) | 181 (10.2) | 173 (9.8) | 118 (6.7) | 218 (12.3) | 47 (2.7) | 205 (11.6) | |

| College degree or graduate school | 446 (46.0) | 128 (13.2) | 67 (6.9) | 32 (3.3) | 129 (13.3) | 22 (2.3) | 145 (15.0) | |

| Income per month | [lt].001 | |||||||

| None | 269 (39.2) | 67 (9.8) | 141 (20.6) | 69 (10.1) | 78 (11.4) | 11 (1.6) | 51 (7.4) | |

| $1–800 | 542 (41.4) | 123 (9.4) | 182 (13.9) | 106 (8.1) | 166 (12.7) | 44 (3.4) | 145 (11.1) | |

| $801–1,600 | 612 (50.0) | 120 (9.8) | 125 (10.2) | 87 (7.1) | 135 (11.0) | 24 (2.0) | 122 (10.0) | |

| $1,601 or more | 424 (50.7) | 113 (13.5) | 68 (8.1) | 46 (5.5) | 75 (9.0) | 19 (2.3) | 92 (11.0) | |

| Body mass index | [lt].001 | |||||||

| Underweight | 42 (31.3) | 9 (6.7) | 14 (10.4) | 30 (22.4) | 19 (14.2) | 4 (3.0) | 16 (11.9) | |

| Normal | 680 (40.9) | 175 (10.5) | 188 (11.3) | 147 (8.8) | 238 (14.3) | 44 (2.6) | 192 (11.5) | |

| Overweight | 520 (49.1) | 107 (10.1) | 145 (13.7) | 55 (5.2) | 86 (8.1) | 27 (2.5) | 119 (11.2) | |

| Obese | 648 (49.5) | 143 (10.9) | 175 (13.4) | 81 (6.2) | 135 (10.3) | 24 (1.8) | 104 (7.9) | |

| Receiving public assistance | [lt].001 | |||||||

| No | 1,186 (42.6) | 293 (10.5) | 311 (11.2) | 189 (6.8) | 385 (13.8) | 72 (2.6) | 349 (12.5) | |

| Yes | 704 (50.9) | 141 (10.2) | 211 (15.3) | 124 (9.0) | 93 (6.7) | 27 (2.0) | 82 (5.9) | |

| Trouble paying for basic expenses | .002 | |||||||

| No | 1,131 (45.3) | 261 (10.5) | 311 (12.5) | 155 (6.2) | 300 (12.0) | 57 (2.3) | 281 (11.3) | |

| Yes | 759 (45.4) | 173 (10.4) | 211 (12.6) | 158 (9.5) | 178 (10.7) | 42 (2.5) | 150 (9.0) | |

| Insurance | [lt].001 | |||||||

| None | 787 (43.7) | 185 (10.3) | 218 (12.1) | 179 (9.9) | 211 (11.7) | 52 (2.9) | 170 (9.4) | |

| Private | 871 (46.7) | 202 (10.8) | 176 (9.4) | 102 (5.5) | 242 (13.0) | 38 (2.0) | 234 (12.5) | |

| Public | 227 (48.7) | 44 (9.4) | 117 (25.1) | 30 (6.4) | 22 (4.7) | 8 (1.7) | 18 (3.9) | |

| Gravidity | [lt].001 | |||||||

| 0 | 374 (31.6) | 96 (8.1) | 161 (13.6) | 78 (6.6) | 233 (19.7) | 30 (2.5) | 212 (17.9) | |

| 1 | 375 (41.3) | 64 (7.1) | 150 (16.5) | 76 (8.4) | 107 (11.8) | 29 (3.2) | 106 (11.7) | |

| 2 | 398 (52.6) | 84 (11.1) | 77 (10.2) | 53 (7.0) | 78 (10.3) | 16 (2.1) | 51 (6.7) | |

| 3 or higher | 743 (56.3) | 190 (14.4) | 134 (10.2) | 106 (8.0) | 60 (4.5) | 24 (1.8) | 62 (4.7) | |

| Parity | [lt].001 | |||||||

| 0 | 694 (35.0) | 159 (8.0) | 268 (13.5) | 153 (7.7) | 348 (17.5) | 58 (2.9) | 305 (15.4) | |

| 1 | 540 (52.6) | 102 (9.9) | 135 (13.2) | 65 (6.3) | 79 (7.7) | 24 (2.3) | 81 (7.9) | |

| 2 | 416 (57.5) | 97 (13.4) | 74 (10.2) | 53 (7.3) | 37 (5.1) | 14 (1.9) | 33 (4.6) | |

| 3 or higher | 240 (55.6) | 76 (17.6) | 45 (10.4) | 42 (9.7) | 14 (3.2) | 3 (0.7) | 12 (2.8) | |

| Unintended pregnancies | [lt].001 | |||||||

| 0 | 492 (34.9) | 122 (8.7) | 193 (13.7) | 97 (6.9) | 247 (17.5) | 32 (2.3) | 225 (16.0) | |

| 1 | 509 (43.9) | 100 (8.6) | 168 (14.5) | 97 (8.4) | 130 (11.2) | 34 (2.9) | 121 (10.4) | |

| 2 | 368 (52.3) | 84 (11.9) | 77 (10.9) | 54 (7.7) | 61 (8.7) | 15 (2.1) | 45 (6.4) | |

| 3 or more | 516 (58.3) | 127 (14.4) | 83 (9.4) | 63 (7.1) | 38 (4.3) | 18 (2.0) | 40 (4.5) | |

| History of abortion | [lt].001 | |||||||

| No | 1,087 (43.2) | 238 (9.5) | 355 (14.1) | 166 (6.6) | 321 (12.7) | 51 (2.0) | 300 (11.9) | |

| Yes | 803 (48.7) | 196 (11.9) | 167 (10.1) | 147 (8.9) | 157 (9.5) | 48 (2.9) | 131 (7.9) | |

| History of STI | [lt].001 | |||||||

| No | 1,111 (43.8) | 259 (10.2) | 326 (12.9) | 171 (6.7) | 336 (13.3) | 63 (2.5) | 268 (10.6) | |

| Yes | 779 (47.7) | 175 (10.7) | 196 (12.0) | 142 (8.7) | 142 (8.7) | 36 (2.2) | 163 (10.0) | |

| Any current STI | [lt].001 | |||||||

| No | 1,777 (45.5) | 420 (10.8) | 473 (12.1) | 278 (7.1) | 448 (11.5) | 94 (2.4) | 415 (10.6) | |

| Yes | 113 (43.1) | 14 (5.3) | 49 (18.7) | 35 (13.4) | 30 (11.5) | 5 (1.9) | 16 (6.1) |

LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system; IUD, intrauterine device; DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; OCs, oral contraceptives; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Data are mean±standard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

The baseline demographic and reproductive characteristics stratified by LARC and non-LARC methods can be found in Table 3. Compared to other contraceptive method users, LARC users were older, less educated, have higher BMI, were more likely to rely on public assistance, and have public insurance. They were also more likely to have higher parity, a greater number of unintended pregnancies and abortions, and a history of STI.

Table 3.

Baseline Demographic and Reproductive Characteristics of Users of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive and Non--Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods

| Non--Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods (n=1,321) |

Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods (n=2,846) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 24.1±5.1 | 25.8±5.9 | [lt].001 |

| Race | .535 | ||

| African American | 637 (48.5) | 1,330 (46.9) | |

| White | 577 (43.9) | 1,297 (45.8) | |

| Others | 100 (7.6) | 207 (7.3) | |

| Education | .004 | ||

| High school diploma or less | 404 (30.6) | 1,020 (35.9) | |

| Some college | 588 (44.5) | 1,184(41.6) | |

| College degree or graduate school | 328 (24.8) | 641 (22.5) | |

| Income per month | .001 | ||

| None | 209 (16.5) | 477(17.1) | |

| $1–800 | 461 (36.3) | 847 (30.4) | |

| $801–1,600 | 368 (29.0) | 857 (30.8) | |

| $1,601 or more | 232 (18.3) | 605 (21.7) | |

| Body mass index | [lt].001 | ||

| Underweight | 69 (5.2) | 65 (2.3) | |

| Normal | 621 (47.0) | 1,043 (36.6) | |

| Overweight | 287 (21.7) | 772 (27.1) | |

| Obese | 344 (26.0) | 966 (33.9) | |

| Receiving public assistance | [lt].001 | ||

| No | 995 (75.3) | 1,790 (62.9) | |

| Yes | 326 (24.7) | 1,056 (37.1) | |

| Trouble paying for basic expenses | .906 | ||

| No | 793 (60.0) | 1,703 (59.8) | |

| Yes | 528 (40.0) | 1,143 (40.2) | |

| Insurance | [lt].001 | ||

| None | 612 (46.9) | 1,190 (42.1) | |

| Private | 616 (47.2) | 1,249 (44.2) | |

| Public | 78 (6.0) | 388 (13.7) | |

| Gravidity | [lt].001 | ||

| 0 | 553 (41.9) | 631 (22.2) | |

| 1 | 318 (24.1) | 589(20.7) | |

| 2 | 198 (15.0) | 559 (19.6) | |

| 3 or higher | 252 (19.1) | 1,067 (37.5) | |

| Parity | [lt].001 | ||

| 0 | 864 (65.4) | 1,121 (39.4) | |

| 1 | 249 (18.8) | 777(27.3) | |

| 2 | 137 (10.4) | 587 (20.6) | |

| 3 or higher | 71 (5.4) | 361 (12.7) | |

| Unintended pregnancies | [lt].001 | ||

| 0 | 601 (45.6) | 807 (28.4) | |

| 1 | 382 (29.0) | 777 (27.4) | |

| 2 | 175 (13.3) | 529 (18.6) | |

| 3 or more | 159 (12.1) | 726 (25.6) | |

| History of abortion | .007 | ||

| No | 838 (63.4) | 1,680 (59.0) | |

| Yes | 483 (36.6) | 1,166 (41.0) | |

| History of STI | .018 | ||

| No | 838 (63.4) | 1,696 (59.6) | |

| Yes | 483 (36.6) | 1,150 (40.4) | |

| Any current STI | .687 | ||

| No | 1,235 (93.5) | 2,670 (93.8) | |

| Yes | 86 (6.5) | 176 (6.2) |

STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Data are mean±standard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Continuation rates for LARC methods ranged from 83 – 88%, with the highest continuation rate for the LNG-IUS (88%) and copper IUD (84%). Women using the implant also had very high rates of continuation at one year (83%). The difference in 12-month continuation rates between IUDs and the implant was not statistically significant (HRR=1.23; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.97, 1.58), or clinically significant (87% versus 83%, respectively). Twelve-month continuation rates for non-LARC methods were as follows: 57% DMPA, 55% OCs, 54% ring, and 49% patch. There were no significant difference in continuation between these non-LARC methods.

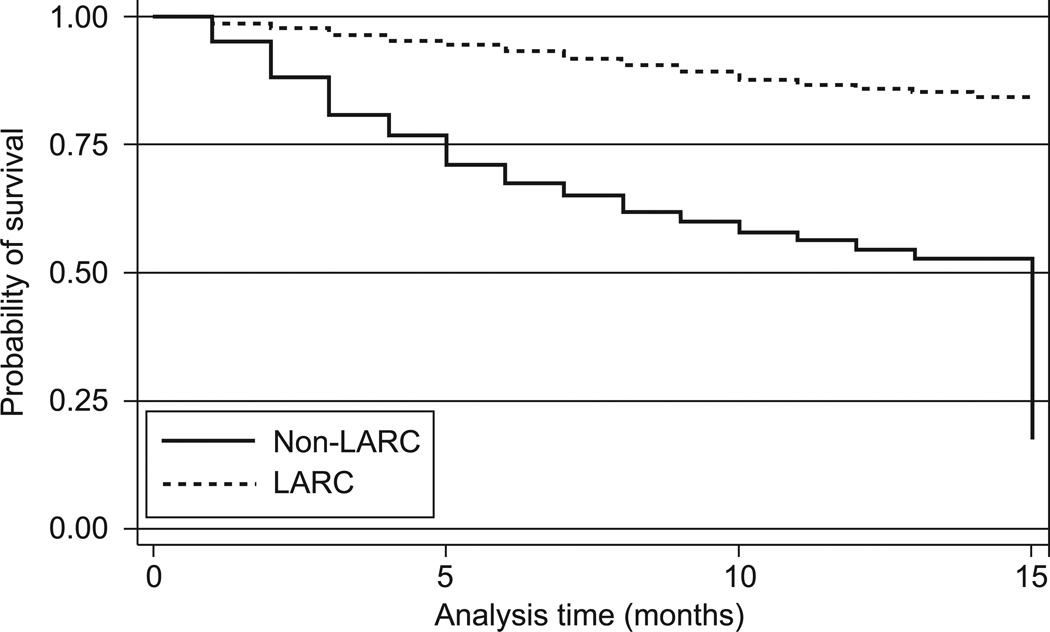

For our survival analysis, we focused on discontinuation of contraceptive methods. Compared to LARC users, non-LARC users were more likely to discontinue the use of their method at 12 months (45.3% versus 13.8%; HRR=4.11, 95% CI 3.61, 4.68; Table 4 and Figure 1). OC users had higher 12-month discontinuation rates than LARC users (HRR=4.13, 95% CI 3.48, 4.89). More specifically, OC users had higher discontinuation rates than both IUDs and the implant (IUDs: HRR=4.30, 95% CI 3.60, 5.14; implant: HRR=3.49, 95% CI 2.70, 4.50). The most common reason for discontinuation of either IUD was bleeding and/or cramping; 14% of all copper IUD users and 5% of all LNG-IUS users reported discontinuing the method for these reasons. Additionally 3% of LNG-IUS users reported discontinuation of the method due to side effects such as acne and weight change. The most common reason for discontinuation of the implant was unpredictable bleeding (10%).

Table 4.

Continuation and Satisfaction at 12 Months by Contraceptive Method

| Starting n | Continuation (%) | n* | Very Satisfied | Somewhat Satisfied | Not Satisfied | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNG-IUS | 1,890 | 87.5 | 1,809 | 1,274 (70.4) | 277 (15.3) | 258 (14.3) |

| Copper IUD | 434 | 84.0 | 407 | 267 (65.6) | 59 (14.5) | 81 (19.9) |

| Implant | 522 | 83.3 | 493 | 270 (54.8) | 118 (23.9) | 105 (21.3) |

| DMPA | 313 | 56.5 | 300 | 127 (42.3) | 35 (11.7) | 138 (46.0) |

| OCs | 478 | 55.1 | 461 | 189 (41.0) | 58 (12.6) | 214 (46.4) |

| Patch | 99 | 49.1 | 97 | 34 (35.1) | 9 (9.3) | 54 (55.7) |

| Ring | 431 | 54.2 | 423 | 197 (46.6) | 26 (6.1) | 200 (47.3) |

| Long-acting reversible contraceptive | 2,846 | 86.2 | 2,709 | 1,811 (66.9) | 454 (16.8) | 444 (16.4) |

| Non--long-acting reversible contraceptive | 1,321 | 54.7 | 1,281 | 547 (42.7) | 128 (10.0) | 606 (47.3) |

LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system; IUD, intrauterine device; DMPA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; OC, oral contraceptive.

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Number is different because participants were loss to follow-up or did not answer satisfaction question.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curve estimating continuation rates for long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) compared with non–long-acting reversible contraception methods.

Satisfaction rates for LARC and non-LARC methods are also shown in Table 4. These rates mirror the continuation rates. This is not unexpected, given that all discontinuers were considered “not satisfied” with their method. Satisfaction was highest for IUDs with over 80% satisfied, of which 66–70% reported being very satisfied. Satisfaction with the implant was also quite high with 79% satisfied, of which 55% reported being very satisfied. Comparing LARC and non-LARC methods, we see that 84% of participants were satisfied with their LARC method at 12-months, compared to 53% of participants using non-LARC methods (RR=1.59; 95% CI 1.50, 1.68).

In the Cox proportional hazard model and the Poisson regression model, we evaluated a number of potential confounders that we believed could be associated with both the contraceptive method and continuation/satisfaction. Race/ethnicity, educational level, parity, body mass index (BMI), income, markers of socioeconomic status, and histories of unintended pregnancy, abortion, or STI were assessed, but none of these variables made a significant (> 10%) change on the effect estimate. Thus, we present unadjusted hazard rate ratios and relative risks. Interestingly, when we evaluated continuation rates and satisfaction within each LARC method stratified by age, the continuation of the LNG-IUS and implants did not vary by age. In women over 20 years of age, 12-month continuation rates were 88% for LNG-IUS and 85% for the implant. This was very similar to the continuation rates in women age 20 years and younger (85% LNG-IUS and 80% implant). However, compared to women over 20 years of age using the copper IUD, the copper IUD users younger than 21 years of age had a higher discontinuation rate (28% vs. 15%, HR=2.10, 95% CI 1.11, 4.02).

DISCUSSION

In the U.S., there are 6 million pregnancies that occur each year, approximately half are unintended.14 Among women who experience an unintended pregnancy, half report using a contraceptive method in the month when the pregnancy occurred.15,16 Because most women use a contraceptive method with adherence requirements, the majority of pregnancies result from incorrect or inconsistent method use rather than from method failure.17 In order to reduce the number of unintended pregnancies in the U.S., clinicians should be offering the most effective methods of contraception to women as first-line options. LARC methods, including the IUD and the subdermal implant are the most effective methods, forgettable, and not user-dependent. Thus, their “typical use” effectiveness is almost equal to “ideal” effectiveness.

Of the first 4,167 women completing their first 12 months of follow-up in the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, we found that LARC methods have the highest continuation rates and highest levels of satisfaction. Among IUD users, there was higher uptake of the LNG-IUS; however there was little difference in the rates of continuation and satisfaction between the LNG-IUS and the copper IUD. We are unsure why participants were four times more likely to choose LNG-IUS than the copper IUD. The LNG-IUS has non-contraceptive indications, such as improvement of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea, which the copper IUD does not.18 However, both IUDs are highly effective and well tolerated. Other possible reasons for this observed ratio is the direct-to-consumer advertising for the LNG-IUS, and “word of mouth” referrals to the project of women who are pleased and satisfied with LNG-IUS use. We also believe there may be a provider bias in favor of the LNG-IUS. Some providers consider the lighter menstrual flow and reduced dysmenorrhea characteristic of the LNG-IUS to be beneficial and subsequently may influence patient choice. Our finding of similar continuation rates for LNG-IUS and copper IUD are in contrast to some published studies. Godfrey et al. performed a multicenter, randomized, controlled, participant-blinded pilot study of 23 adolescents aged 14–18 years assigned to the copper IUD or LNG-IUS.19 In this study, the 6-month continuation rates were 75% for the LNG-IUS and 45% for the copper IUD – this continuation rate for the copper IUD is in marked contrast to ours. When we stratified our findings by age (< 21 years versus ≥ 21 years), we did find that younger women using the copper IUD were more likely to discontinue compared to older women; however, the younger women’s continuation rate of 72% was still substantially higher than the Godfrey study. This finding was not observed in users of the LNG-IUS. The Godfrey study only included adolescents, and was limited by its small sample size. Additionally, participants randomized to a contraceptive method may be less likely to be satisfied, thus impacting continuation rates.

Suhonen et al. conducted a multicenter, randomized study of 200 women aged 18–25 years assigned to LNG-IUS or OCs. These investigators noted a 12-month continuation rate of 80% for LNG-IUS, compared to 73% for OCs.20 Our findings are very similar, although we had a higher continuation rate for the LNG-IUS, and a much lower continuation rates for OCs. Other studies have also noted high continuation rates for IUDs, in both young women and women of all ages.21

Our continuation rates for all reversible methods of contraception are similar to those quoted by Trussel.21 In our study, women were considered “continuers” as long as they did not stop their method for 4 weeks or longer. This likely overestimated our continuation rate since women who stopped and then restarted a method in the same month would still be considered “continuers” despite potentially being at risk for pregnancy. Lapses in contraceptive use may be due to switching between methods or temporary discontinuation due to an expired prescription, difficulty getting to the pharmacy or healthcare provider, method dissatisfaction, or side effects.16,17 However, even if we overestimated the continuation of non-LARC methods, we can clearly see that the continuation rates are much higher among the LARC methods.

Our study found a 12-month continuation rate of 82% for the subdermal implant, which was higher than we expected. The medical literature is limited, but reported 12-month continuation rates ranged from 68 – 78%. A multicenter clinical trial of 330 women using the implant for 2 years noted a 12-month continuation rate of 68%,22 while a multicenter observational study of 417 women noted a 78% continuation rate at 12-months.23 Wong and colleagues performed an observational cohort study of 211 subdermal implant users and 228 IUD users, and noted a 6-month continuation rate of 83% for the implant and an 89% continuation rate for the IUD.24 As in our study, these investigators found that IUD users were more satisfied than implant users (74% versus 58%, p=0.002).

The strengths of our study include its prospective design, large sample size, and low rate of loss to follow-up at 12 months. Limitations include a convenience sample, inclusion criterion that specified that participants must be willing to try and initiate a new contraceptive method, and lack of randomization. The convenience sample, inclusion criteria, and regional recruitment may limit the generalizability of our study. Since participants are not randomly assigned a contraceptive method, their baseline expectations of a contraceptive method may be different. We did not believe we could ethically randomize patients to a method of contraception, and randomization may adversely impact continuation which was one of our primary outcomes. We required that participants try a new contraceptive method so that we could better compare new IUD or implant users with new users of other methods. The question of how to define continuation in this study was a challenge – we had many participants who stopped and restarted their method. Women who stopped their method for 4 weeks or greater were defined as discontinuers; however, women who temporarily discontinued their method within a 4 week period were counted as ”continuers.” The inclusion of these women as continuers may overestimate the continuation rate and bias our results toward the null; however, it does provide a conservative estimate of the effect size.

In conclusion, LARC methods have the highest rates of user satisfaction and continuation of all reversible contraceptive methods. Because they are also the most effective reversible methods of contraception, they should be the methods of choice (first-line option) for women trying to avoid an unintended pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project is funded by an Anonymous Foundation. This research was also supported in part by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Women’s Health Research (K24 HD01298), by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR024992), K12HD001459 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD); and by Grant Number KL2RR024994 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Eisenberg receives research funding from an anonymous foundation, the Society of Family Planning, and an ACOG/Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals award for research in long-acting reversible contraception. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of Contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2010:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilliam ML, Neustadt A, Kozloski M, Mistretta S, Tilmon S, Godfrey E. Adherence and acceptability of the contraceptive ring compared with the pill among students: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;115:503–510. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cf45dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg MJ, Waugh MS. Oral contraceptive discontinuation: a prospective evaluation of frequency and reasons. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:577–582. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Picardo C, Ferreri S. Pharmacist-administered subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2010;82:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sangi-Haghpeykar H, et al. Experiences of injectable contraceptive users in an urban setting. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(2):227–333. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westfall JM, Main DS, Barnard L. Continuation rates among injectable contraceptive users. Family Plann Perspect. 1996;28(6):275–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming KL, Sokoloff A, Raine TR. Attitudes and beliefs about the intrauterine device among teenagers and young women. Contraception. 2010;82:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madden T, Allsworth JE, Hladky KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Intrauterine contraception in St. Louis: a survey of obstetrician and gynecologists' knowledge and attitudes. Contraception. 2010;81(2):112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hladky KJ, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Knowledge of intrauterine contraception: a population-based survey of St. Louis area women. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318202b4c9. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dehlendorf C, Ruskin R, Grumbach K, Vittinghoff E, Bibbins-Domingo K, Schillinger D, Steinauer J. Recommendations for intrauterine contraception: a randomized trial of the effects of patients’ race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:319.e1–319.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster DG. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):446–451. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Aug;203(2):115.e1–115.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 May 15;157(10):940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RK, et al. Occasional Report. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2006. Repeat abortion in the United States; p. No 29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in the rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 – 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(2):90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frost JJ, Darroch JE. Factors associated with contraceptive choice and inconsistent method use, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008 Jun;40(2):94–104. doi: 10.1363/4009408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreau C, Cleland K, Trussell J. Contraceptive discontinuation attributed to method dissatisfaction in the United States. Contraception. 2007;76(4):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser IS. Non-contraceptive health benefits of intrauterine hormonal system. Contraception. 2010;82:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godfrey EM, Memmel LM, Neustadt A, Shah M, Nicosia A, Moorthie M, Gilliam M. Intrauterine contraception for adolescents aged 14–18 years: a multicenter randomized pilot study of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system compared to the Copper T 380A. Contraception. 2010 Feb;81(2):123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suhonen S, Haukkamaa M, Jakobsson T, Rauramo I. Clinical performance of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and oral contraceptives in young nulliparous women: a comparative study. Contraception. 2004;69:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trussell J. Contraceptive efficacy. In: Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Stewart FH, Kowal D, editors. Contraceptive technology. 19th revised. New York: Ardent Media; 2007. p. 759. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funk S. Safety and efficacy of Implanon, a single-rod implantable contraceptive containing etonogestrel. Funk S et al. Contraception. 2005;71:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flores JB, Balderas ML, Bonilla MC, Vazquez-Estrada L. Clinical experience and acceptability of the etonogestrel subdermal contraceptive implant. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005 Sep;90(3):228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong RC, Bell RJ, Thunuguntla K, McNamee K, Vollenhoven B. Implanon users are less likely to be satisfied with their contraception after 6 months than IUD users. Contraception. 2009;80:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]