Abstract

Using cell fractionation and measurement of Fe(III)heme-pyridine, the antimalarial chloroquine (CQ) has been shown to cause a dose-dependent decrease in hemozoin and concomitant increase in toxic “free” heme in cultured Plasmodium falciparum that is directly correlated with parasite survival. Transmission electron microscopy techniques have further shown that heme is redistributed from the parasite digestive vacuole to the cytoplasm and that CQ disrupts hemozoin crystal growth, resulting in mosaic boundaries in the crystals formed in the parasite. Extension of the cell fractionation study to other drugs has shown that artesunate, amodiaquine, lumefantrine, mefloquine and quinine, all clinically important antimalarials, also inhibit hemozoin formation in the parasite cell, while the antifolate pyrimethamine and its combination with sulfadoxine do not. This study finally provides direct evidence in support of the hemozoin inhibition hypothesis for the mechanism of action of CQ and shows that other quinoline and related antimalarials inhibit cellular hemozoin formation.

During its pathogenic blood stage the malaria parasite faces the unique problem of disposing of vast quantities of toxic heme derived from the digestion of host hemoglobin.(1) It accomplishes this by crystallizing at least 95% as insoluble hemozoin.(2) Important antimalarial drugs are believed to inhibit this process. Heme has long been proposed to be the target of CQ and inhibition of the synthetic counterpart of hemozoin has been demonstrated many times,(3–9) but direct evidence of hemozoin inhibition with increased free heme in the parasite has never been conclusively demonstrated. The recent discovery of thousands of new antimalarially active compounds by high-throughput whole-cell screening has shifted priorities to the discovery of their targets and modes of action, which will doubtless include inhibition of hemozoin formation.(8, 10) Herein we show that CQ inhibits hemozoin formation, with a corresponding increase in free heme correlated with parasite death. We also demonstrate the effects of CQ on both cellular heme distribution in the malaria parasite and on the hemozoin crystal. The approach provides a basis for assaying parasite hemozoin inhibition in the presence of antimalarial compounds.

CQ-sensitive P. falciparum cells (D10 strain) grown in synchronous culture for 32 h are known to digest roughly 60% of host hemoglobin and have been reported to contain 58 ± 2 fg of Fe per cell.(2) When the parasites were exposed to increasing doses of CQ, or fixed doses (2.5 × IC50) of a number of other antimalarials over the 32 h growth period, somewhat surprisingly there was no statistically significant change in total cellular iron content in isolated trophozoites (Figure 1a). Total heme content of control, CQ-treated and pyrimethamine- or sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine- (SP-) treated cells was also unchanged. Owing to the overwhelming preponderance of hemoglobin-derived heme in trophozoite stage parasites, the total heme content was statistically indistinguishable from the total iron content (average values of 58 ± 7 fg/cell total Fe vs. 61 ± 7 fg/cell heme Fe for CQ-treated parasites, n = 6, P = 0.38). This agrees with previous evidence that at least 95% of the iron in untreated P. falciparum trophozoites is heme iron in the form of hemozoin.(2

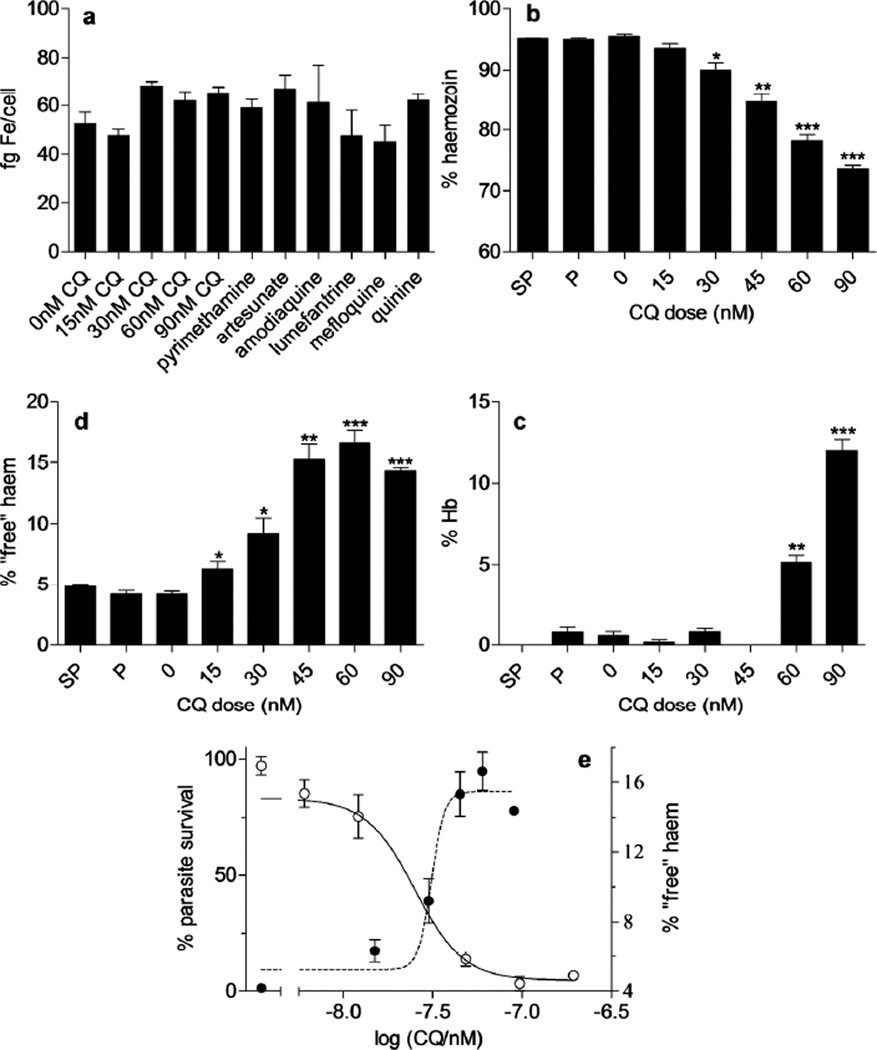

Figure 1.

Iron and heme species in untreated and drug-treated parasites. a Total Fe content of untreated and drug treated trophozoites exposed to varying concentrations of CQ, or other antimalarials at 2.5 times their respective IC50 values. Parasites were synchronized with sorbitol and cultured for 32 h with or without drug. Total iron was measured using the ferrozine method of Carter.(11) None of the measurements shown are significantly different from the control value, 0 nM CQ, (P > 0.05, n = 4, 4, 3, 7, 3, 5, 7, 3, 4, 4 and 4 respectively). Fraction of total heme present as b hemozoin (fraction 4), c “free” heme (fraction 3) and d Hb (fraction 2). Asterisks indicate statistical significance relative to control (2-tailed t-test): * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001, n = 3 except for pyrimethamine (P) where n = 6. e Parasite survival curve (open circles, left axis) determined using the lactate dehydrogenase assay of Makler et al.(12) and percentage “free” heme (closed circles, right axis) as a function of CQ dose.

To examine the effects of CQ on the fate of heme in the malaria parasite, a cell fractionation strategy was used (Figure 2). Exposure of P. falciparum to CQ caused a dose-dependent decrease in the fraction of total heme present as hemozoin. This decreased from 95% in untreated parasites to about 74% in CQ treated parasites at 90 nM CQ (Figure 1b). At higher doses, too few parasites survived to obtain reliable measurements. Nonetheless, the dose-dependent decrease is clearly demonstrated by the statistically significant decrease observed from 0 – 90 nM. A crucial point is that the decrease in the fraction of heme present as hemozoin was matched by a rise in both “free” heme and hemoglobin (Hb). The former corresponds to heme that can be solubilized by inclusion of 2% SDS and 5% v/v pyridine in the suspension medium and may be membrane associated. The statistically significant dose-dependent increase in Hb observed from 60 nM CQ onwards (Figure 1d) is in agreement with other studies that have provided evidence of undigested Hb in CQ-treated parasites either spectroscopically or using gel electrophoresis.(13, 14) Dose-dependent increase of “free” heme has previously been suggested in connection with a hypothesis of heme degradation in the parasite,(15) but its direct link to decreased hemozoin formation has never previously been demonstrated (Figure 1c). The dose-response curve for the increase in “free” heme fraction is tightly correlated with the parasite growth inhibition dose-response curve (Figure 1e), with “free” heme appearing before undigested Hb and strongly suggesting a causal link. By contrast, the antifolates pyrimethamine (P) and SP have no significant effect on hemozoin, “free” heme or Hb levels in the cell.

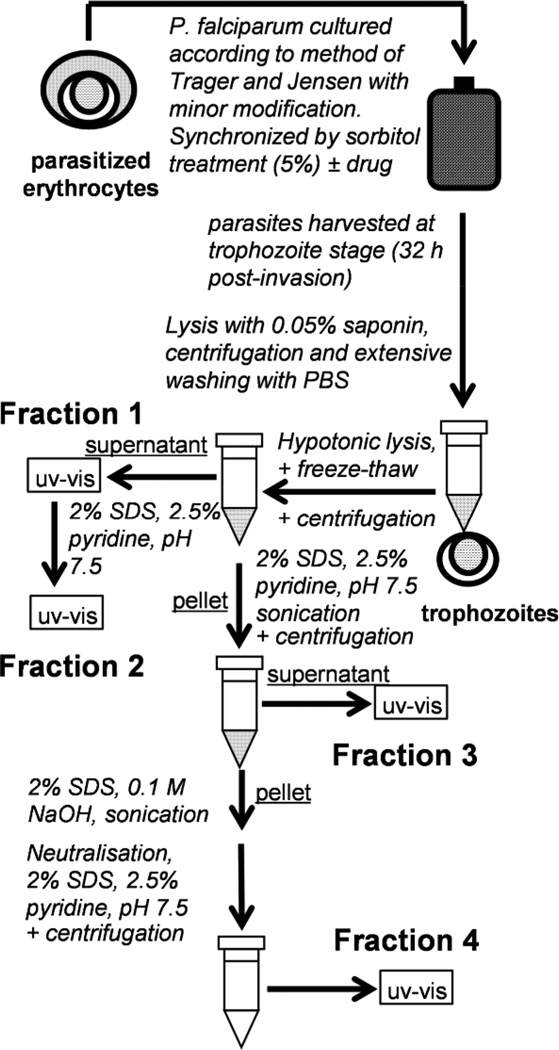

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of the strategy for measuring heme species in different cellular fractions. Parasites were cultured according to the method of Trager and Jensen.(16) The spectrum of fraction 1 was characteristic of Hb. The heme content of the remaining fractions were then measured using 2% SDS and 2.5% pyridine to form a heme-pyridine complex (based on a reported method for heme quantification).(17)

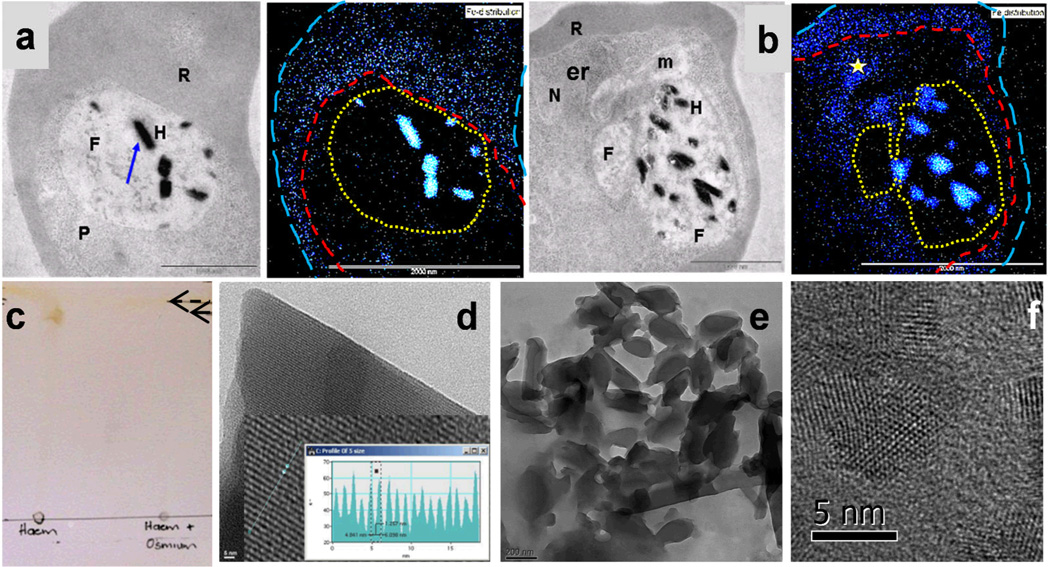

The effect of CQ on the distribution of iron within the parasite was examined with electron spectroscopic imaging (ESI) using electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) (Figure 3a and b). Control parasites contained very little iron relative to red blood cell (RBC) cytoplasm in the merozoite or ring stages (not shown), but a great deal of hemozoin iron at the trophozoite stage (Figure 3a), as expected. In accordance with previous studies,(2) and heme measurements described above, iron concentrations in the rest of the parasite were very much lower than in the RBC cytoplasm (Figure 3a). When parasites were exposed to 30, 60 or 120 nM CQ, no change was observed at either the merozoite or ring stages (not shown). At 30 nM CQ a dramatic increase in cytoplasmic iron concentration could be seen at the trophozoite stage in a region of the malaria parasite that may correspond to the endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 3b). Surprisingly, there was no increase in iron in the digestive vacuole (DV) and hemozoin crystals were still sharply delineated. Since chemical fixation was used in preparing samples, it is important to consider whether iron may have been redistributed. Three lines of evidence strongly argue against this. Firstly, the control experiments with untreated trophozoites (Figure 3a), as well as images of merozoites and ring-stage parasites (not shown), unequivocally demonstrated that neither Hb iron, nor hemozoin iron is mobilized during fixation. A sharp delineation was seen between RBC cytoplasm and the parasite and sharp edges to the hemozoin signal were observed. This is in agreement with the observation of minimal non-hemozoin iron in untreated trophozoites at 32 h. Secondly, in treated parasites there was a sharp iron concentration gradient between the parasite cytoplasm and DV (Figure 3b). If iron had diffused out of the DV during processing this ought to have resulted in a uniform distribution at equilibrium, especially since the parasites are dead throughout exposure to fixing solvents, so no pH or energy gradients are expected between different compartments. Thirdly, OsO4 fixes heme. This is confirmed by thin layer chromatography which showed that hemin (Cl-Fe(III)protoporphyrin IX) is immobilized following exposure to OsO4 (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

TEM images of control and treated parasitized RBCs with iron distribution (blue) measured by ESI using EELS. a Untreated trophozoites show negligible Fe except for the strong signal from hemozoin (e.g. crystal marked by arrow). On the other hand, Fe is readily detected in the RBC cytoplasm. Note the sharp gradient in Fe signal between RBC and parasite and at the edges of hemozoin crystals indicating that Fe distribution is not affected by fixation. b Parasites treated with 30 nM CQ clearly exhibit iron in the parasite cytoplasm at the trophozoite stage, especially concentrated in regions such as that indicated by the star. Note the low Fe signal in the DV apart from hemozoin. Since almost all Fe in both control and treated parasites is present as heme species, this Fe distribution can be attributed to the heme distribution. Furthermore, since there is little Hb present in trophozoites treated with 30 nM CQ, the heme present in the parasite cytoplasm is probably the “free” heme fraction. RBCs delineated by long blue dashes, parasite by short red dashes and DV by yellow dots in the ESI images. Samples were prepared as described in a previous report.(2) (c) A thin layer chromatogram run in acetone shows that heme is completely immobilized by OsO4 treatment. Similar results were seen in ethanol and aqueous ethanol (not shown). (d) Extracted, untreated hemozoin crystals are highly ordered, with uniform diffraction fringes throughout the crystals. An enlargement of the crystal is shown in inset in which the fringes can be more clearly seen. A measurement of intensity along the blue line in the enlargement permits measurement of the lattice spacing which corresponds closely to that expected for the {100} face of hemozoin (12.57 Å).(18) (e) Extracted hemozoin crystals from parasites treated with 30 nM CQ are less uniform. (f) Grain boundaries are clearly visible at 60 nM CQ. In (a) and (b) R = RBC, P = parasite, F = DV, H = hemozoin, N = probable nucleus, m = mitochondrion and er = possible endoplasmic reticulum. In (c) the solvent front is marked by a dashed arrow and the position of the hemin spot by a solid arrow. Scale bars in d and e are 5 nm and 200 nm, respectively. See Supporting Information.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of hemozoin crystals extracted from control parasites (Figure 3d) revealed that they consisted of single, highly ordered crystals as evidenced by uniform fringes corresponding to the {100} face of the crystal. By contrast, extracted hemozoin crystals from parasites treated with 30 nM CQ were found to be less uniform in external shape (Figure 3e) and at 60 nM CQ there is clear evidence of multiple small crystallites with discernible interfaces between them (grain boundaries) which could be seen at high magnification, demonstrating directly that CQ disrupts the process of hemozoin crystallization in the parasite (Figure 3f).

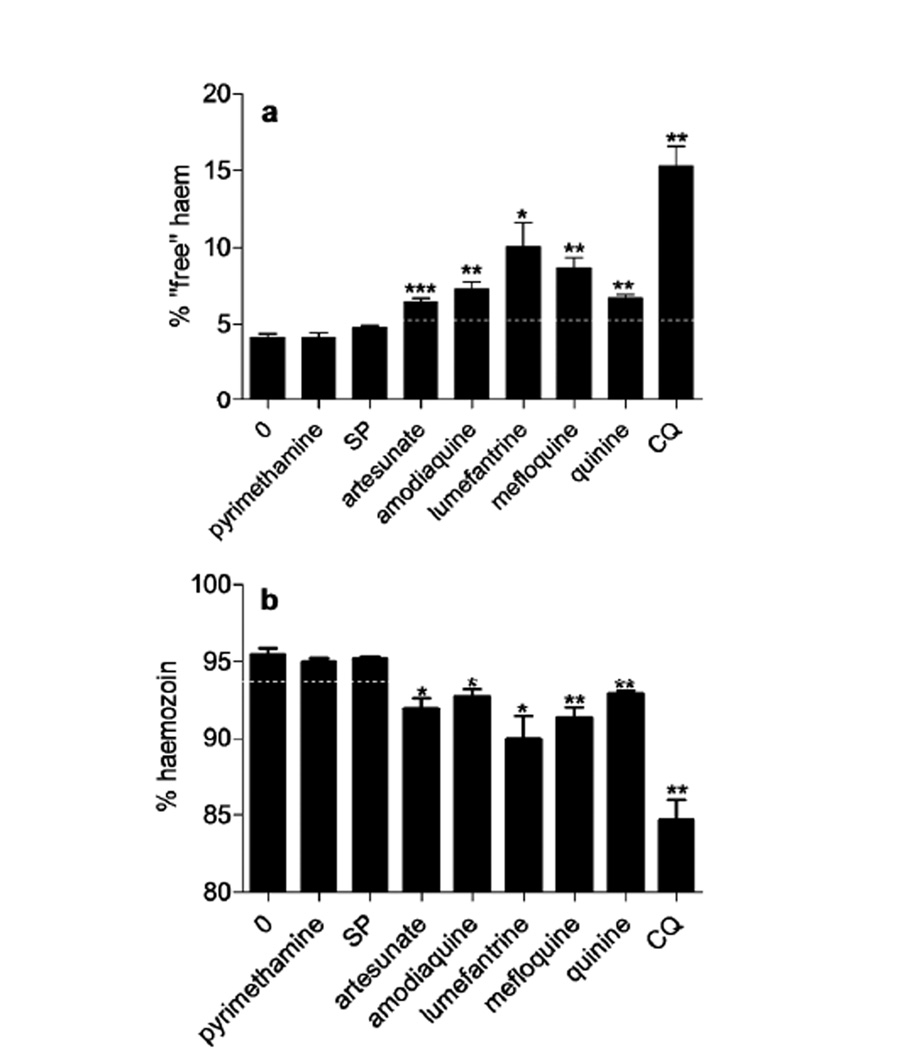

As an initial measure of the effect of other antimalarials on hemozoin formation, the relative quantities of hemozoin and “free” heme in parasites exposed to artesunate, amodiaquine, lumefantrine, mefloquine and quinine at 2.5 times their IC50 values after 32 h exposure was examined. While all of these drugs had no significant effect on total iron content of the parasite, they all caused a statistically significant decrease in hemozoin and increase in “free” heme concentration (Figure 4). All have been claimed to inhibit β-hematin formation in the past.(5, 19, 20) The claim is controversial for artesunate,(21, 22) but the current experiment clearly shows that it does indeed cause a decrease in hemozoin formation and corresponding increase in free heme in the D10 strain of P. falciparum. Interestingly, with the exception of lumefantrine, the increase in “free” heme and decrease in hemozoin upon exposure to drug is significantly less than that for CQ at 2.5 × IC50. This either indicates multiple modes of action of these drugs or differences in toxicity of heme-drug complexes, with these complexes all being more toxic to the parasite. It must be emphasized that more detailed dose-dependence investigations are required to substantiate the mechanism of action of these drugs.

Figure 4.

Effects of single doses of antimalarial drugs on: a “free” heme; and b hemozoin in purified trophozoites cultured in synchrony after 32 h exposure. Drugs were present at 2.5 times their respective IC50 values (except CQ which was present at 45 nM and SP present at 2.5 times the IC50 of pyrimethamine and with 16 mol equivalents of sulfadoxine relative to pyrimethamine). Asterisks indicate statistical significance relative to untreated control (2-tailed t-test): * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001, n = 3 except for artesunate (n = 5), mefloquine (n = 5) and pyrimethamine (labeled P on the graph) (n = 7). The white dotted lines represent three standard deviations in the control values.

These measurements constitute the first direct evidence that CQ actually inhibits hemozoin formation in the malaria cell, with a resulting dose-dependent build-up of “free” heme in a manner closely matching parasite survival. This confirms the proposed mechanism of action of CQ and establishes a benchmark for validation of hemozoin inhibition for other antimalarial compounds. Indeed, measurement of “free” heme and hemozoin at fixed dose provides an initial screen which may be adapted to higher throughput in the near future. Such a test would complement well established genomic, proteomic and metabolomic methods of investigating the effects of antimalarially active compounds on the malaria parasite. It will give a more complete picture of drug effects and be an important tool in the rational choice of compounds for future drug development.

The observation that iron is found in the parasite cytoplasm and not in the DV upon treatment of P. falciparum with CQ is contrary to the long-held assumption that CQ treatment causes an increase in free Fe(III)heme concentration in the DV. However, the low pH of the DV favors the uncharged protonation state of Fe(III)heme and this hydrophobic species is known to enter lipid environments.(23) It is therefore likely that it simply diffuses out of the DV and is deprotonated on encountering the parasite cytoplasm to form an anionic species. This form of Fe(III)heme still tends to interact with membranes,(24) and hence apparently becomes associated with various membranous structures in the parasite cytoplasm, possibly the endoplasmic reticulum. It may be that it is destabilization of organelle membranes in the cell that leads to parasite death, possibly through multiple effects, including, but not limited to disruption of membrane trafficking, ion homeostasis and small molecule transport. This observation merits further investigation.

METHODS

Trophozoites were isolated by saponin lysis, diluted to 1 ml, counted using a hemocytometer and then stored at −80 °C. For measurements, samples were thawed and divided into three 200 µl aliquots, to which 100 µl of water was added before sonication (5 min). HEPES buffer, 100 µl 0.02 M, pH 7.5 and 100 µl water was added and the sample centrifuged. The uv-visible spectrum of the supernatant was recorded and then 100 µl of 4% SDS added the mixture, sonicated and incubated at room temperature (30 min). 100 µl of 0.3 M NaCl and 100 µl of 25% pyridine (v/v) were added and the solution diluted to 1 ml. The uv-visible spectrum (fraction 2) was recorded. 100 µl of water was added to the pellet, followed by 100 µl of 4% SDS. After vortexing, the solution was sonicated and incubated (30 min) at room temperature. 100 µl 0.2 M HEPES pH 7.5, 100 µl 0.3 M NaCl and 100 µl 25% pyridine were added and the sample centrifuged. The supernatant was diluted to 1 ml with water. The uv-visible spectrum was recorded (fraction 3). The remaining pellet was treated with 100 µl of water and 100 µl of 0.3 M NaOH, vortexed, sonicated (60 min) and incubated (30 min) at room temperature. 100 µl 0.2 M HEPES pH 7.5, 100 µl 0.3 M HCl and 100 µl 25% pyridine were added and the supernatant was diluted to 1 ml. The uv-visible spectrum was recorded (fraction 4). Where necessary this fraction was diluted. Percentages of the three heme species (fractions 2 – 4) were determined from the absorbance values (see Supporting Information). Total heme in each sample was quantified using a standard curve.

For TEM parasites from synchronous cultures were enriched by percoll density gradient centrifugation, fixed with 5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4, 10 min, room temperature). Following a PBS wash, the cells were re-suspended in 1 ml 2.5% (v/v) of glutaraldehyde in PBS and left at 4°C overnight for further fixation. The samples were post-fixed with 1% OsO4 in PBS for 1 h, washed twice with distilled water and suspended in 1% agarose. Samples were then cut into 1 mm cubes and dehydrated with aqueous ethanol (30% — 95% for 5 min, 2 × 100% ethanol for 10 min) and twice with acetone (10 min). Acetone was gradually replaced with Spurr’s epoxy resin over two days and allowed to harden (16 h, 60°C). Blocks were trimmed and cut into ultrathin sections with a Reichert Ultracut S ultratome using diamond knives and picked up on 200 mesh square copper grids. The copper grids were then stained with 1% uranyl acetate and 1% lead citrate and washed thoroughly with distilled water.

TEM and electron spectroscopic imaging (ESI) were performed on a LEO 912 OMEGA transmission electron microscope using a slit width of 18 eV on a Tiedtz charge-coupled-devise camera (1024 × 1024 pixels) and processed with analySIS software from Soft Imaging System using a two window difference method. Images were recorded at energies before the Fe L3 absorption edge (658 eV and 688 eV) and the third was centered at 718 eV. The background image was then extrapolating from the data at 658 eV and 688 eV and subtracted from the image collected at 718 eV (see Supporting Information).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank B.T. Sewell and M. Jaffer, Electron Microscope Unit, University of Cape Town for helpful suggestions and assistance with the electron microscopy. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa, the National Research Foundation, the South African Malaria Initiative and in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grant 1R01AI083145-04. The opinions expressed do not represent those of the funding agencies involved.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tilley L, Dixon MWA, Kirk K. The Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cell. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011;43:839–842. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan TJ, Combrinck JM, Egan J, Hearne GR, Marques HM, Ntenteni S, Sewell BT, Smith PJ, Taylor D, van Schalkwyk DA, Walden JC. Fate of haem iron in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. J. 2002;365:343–347. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou AC, Chevli R, Fitch CD. Ferriprotoporphyrin IX fulfills the criteria for identification as the chloroquine receptor of malaria parasites. Biochemistry. 1980;19:1543–1549. doi: 10.1021/bi00549a600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slater AFG, Cerami A. Inhibition by chloroquine of a novel haem polymerase enzyme activity in malaria trophozoites. Nature. 1992;355:167–169. doi: 10.1038/355167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan TJ, Ross DC, Adams PA. Quinoline anti-malarial drugs inhibit spontaneous formation of b-haematin (malaria pigment) FEBS Lett. 1994;352:54–57. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan DJ, Gluzman IY, Russell DG, Goldberg DE. On the molecular mechanism of chloroquine's antimalarial action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11865–11870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rush MA, Baniecki ML, Mazitschek R, Cortese JF, Wiegand R, Clardy J, Wirth DF. Colorimetric high-throughput screen for detection of heme crystallization inhibitors. Antimicr. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2564–2568. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01466-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guiguemde WA, Shelat AA, Bouck D, Duffy S, Crowther GJ, Davis PH, Smithson DC, Connelly M, Clark J, Zhu F, Jiménez-Díaz MB, Martinez MS, Wilson EB, Tripathi AK, Gut J, Sharlow ER, Bathhurst I, El Mazouni F, Fowble JW, Forquer I, McGinley PL, Castro S, Angulo-Barturen I, Ferrer S, Rosenthal PJ, DeRisi JL, Sullivan DJ, Lazo JS, Roos DS, Riscoe MK, Phillips MA, Rathod PK, Van Voorhis WC, Avery VM, Guy RK. Chemical genetics of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2010;465:311–315. doi: 10.1038/nature09099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandlin RD, Carter MD, Lee PJ, Auschwitz JM, Leed SE, Johnson JD, Wright DW. Use of the NP-40 detergent-mediated assay in discovery of inhibitors of b-hematin crystallization. Antimicr. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3363–3369. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00121-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamo F-J, Sanz LM, Vidal J, de Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera J-L, Vanderwall DE, Green DVS, Kumar V, Hasan S, Brown JR, Peishoff CE, Cardon LR, Garcia-Bustos JF. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature. 2010;465:305–312. doi: 10.1038/nature09107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter P. Spectrophotometric determination of serum iron at the submicrogram level with a new reagent (ferrozine) Anal. Biochem. 1971;40:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makler MT, Ries JM, Williams JA, Bancroft JE, Piper RC, Gibbins BL, Hinrichs DJ. Parasite lactate dehydrogenase as an assay for Plasmodium falciparum drug sensitivity. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993;48:739–741. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krugliak M, Zhang F, Ginsburg H. Intraerythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum utilizes only a fraction of the amino acids derived from the digestion of host cell cytosol for the biosynthesis of its proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2002;119:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts L, Egan TJ, Joiner K, Hoppe HC. Differential effects of quinoline qntimalarials on endocytosis in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicr. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1840–1842. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01478-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginsburg H, Famin O, Zhang F, Krugliak M. Inhibition of glutathione-dependent degradation of heme by chloroquine and amodiaquine as a possible basis for their antimalarial mode of action. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;56:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ncokazi KK, Egan TJ. A colorimetric high-throughput b-hematin inhibition screening assay for use in the search for antimalarial compounds. Anal. Biochem. 2005;338:306–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagola S, Stephens PW, Bohle DS, Kosar AD, Madsen SK. The structure of malaria pigment (b-haematin) Nature. 2000;404:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorn A, Vippagunta SR, Matile H, Jaquet C, Vennerstrom JL, Ridley RG. An assessment of drug-haematin binding as a mechanism for inhibition of haematin polymerisation by quinoline antimalarials. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;55:727–736. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loup C, Lelievre J, Benoit-Vical F, Meunier B. Trioxaquines and heme-artemisinin adducts inhibit the in vitro formation of hemozoin better than chloroquine. Antimicr. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3768–3770. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckstein-Ludwig U, Webb RJ, van Goethem IDA, East JM, Lee AG, Kimura M, O'Neill PM, Bray PG, Ward SA, Krishna S. Artemesinins target the SERCA of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2003;424:957–961. doi: 10.1038/nature01813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes RK, Monti D, Taramelli D, Basilico N, Parapini S. Artemisinin antimalarials do not inhibit hemozoin formation. Antimicr. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1175. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.1175.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoang AN, Sandlin RD, Omar A, Egan TJ, Wright DW. The neutral lipid composition present in the digestive vacuole of Plasmodium falciparum concentrates heme and mediates β-hematin formation with an unusually low activation energy. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10107–10116. doi: 10.1021/bi101397u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt TH, Frezzatti WA, Schreier S. Hemin-induced lipid membrane disorder and increased permeability: a molecular model for the mechanism of cell lysis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;307:96–103. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.