Abstract

The first demonstrated example of a regulatory function for a bacterial hemerythrin (Bhr) domain is reported. Bhrs have a characteristic sequence motif providing ligand residues for a type of non-heme diiron site that is known to bind O2 and undergo autoxidation. The amino acid sequence encoded by the gene, VC1216, from Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. N16961 contains an N-terminal Bhr domain connected to a C-terminal domain characteristic of bacterial di-guanylate cyclases (DGCs) that catalyze formation of cyclic di-(3′,5′)-guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) from GTP. This protein, Vc Bhr-DGC, was found to contain two tightly bound non-heme iron atoms per protein monomer. The as-isolated protein showed the spectroscopic signatures of oxo/dicarboxylato-bridged non-heme diferric sites of previously characterized Bhr domains. The diiron site was capable of cycling between diferric and diferrous forms, the latter of which was stable only under anaerobic conditions, undergoing rapid autoxidation upon exposure to air. Vc Bhr-DGC showed approximately 10-times higher DGC activity in the diferrous relative to the diferric form. The level of intracellular c-di-GMP is known to regulate biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. The higher DGC activity of the diferrous Vc Bhr-DGC is consistent with induction of biofilm formation in low dioxygen environments. The non-heme diiron cofactor in the Bhr domain thus represents an alternative to heme or flavin for redox and/or diatomic gas sensing and regulation of DGC activity.

Cyclic di-(3′,5′)-guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) is a ubiquitous bacterial “second messenger”, regulating processes such as biofilm formation, motility and virulence.1–5 A prime exemplar is Vibrio choleraeEL, the causative agent of human epidemic cholera. Biofilm formation facilitates survival of V. cholerae and is positively controlled by c-di-GMP levels.6–8 By contrast, lower c-di-GMP levels promote motility and virulence of V. cholerae.9–11

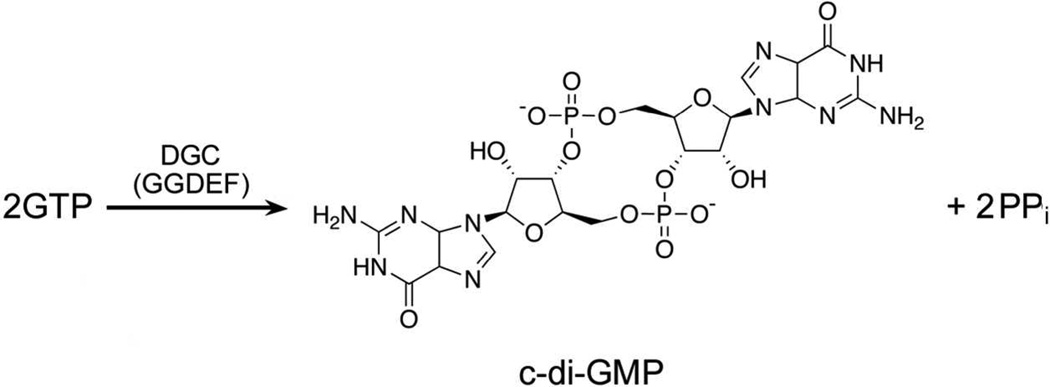

C-di-GMP formation is catalyzed by di-guanylate cyclases (DGCs), which convert two GTPs into one c-di-GMP and two inorganic pyrophosphates (PPi), as shown in Scheme 1. DGCs are often referred to as GGDEF proteins due to their characteristic active site sequence motif. Many bacteria contain multiple genes encoding GGDEF proteins.12

Scheme 1.

Most DGCs are chimeric proteins containing a GGDEF domain and at least one additional domain which regulates DGC activity.3,12–14 Phosphorylation of a response regulator receiver domain or changes in quaternary structure have been implicated in regulating activities of some DGCs.3,13,15,16 Activities of other chimeric DGCs are known to be regulated by redox changes of heme- or flavin-containing domains.17–20 Two full-length chimeric DGCs have been structurally characterized.15,16,21 Their minimum functional units consist of homodimers in which two GGDEF domains directly contact each other with the active sites spanning subunit interfaces. GGDEF domains in DGCs also typically contain non-competitive product inhibition sites having a characteristic RXXD sequence motif.

At least 40 genes in a wide variety of bacteria encode chimeric proteins containing a DGC domain and a second domain with a sequence characteristic of a class of non-heme diiron proteins called bacterial hemerythrin (Bhr).22,23 Bhrs contain a characteristic sequence motif found in a class of invertebrate non-heme diiron O2-binding proteins called hemerythrin (Hr).24,25 Xiong et al. isolated and characterized the first example of a Bhr domain, DcrH-Hr, as a soluble protein derived from a much larger transmembrane protein referred to as Desulfovibrio chemoreceptor protein H (DcrH).26 The DcrH-Hr X-ray crystal structure was subsequently solved in the diferric, diferrous and mixed-valent forms.27,28 The DcrH-Hr structure closely resembles those of invertebrate Hrs, featuring a four-helix bundle protein backbone surrounding an oxo,dicarboxylato-bridged diiron site with terminal His ligands. The diferrous DcrH-Hr formed the expected O2 adduct, but this adduct underwent relatively rapid autoxidation to the diferric form (t1/2 < 1 min at room temperature vs ~20 hr for invertebrate Hrs).26,28 Two other Bhrs were subsequently isolated and characterized;29–32 they both contained diiron sites with spectroscopic and redox properties very similar to those of DcrH-Hr. Hundreds of Bhr homologues have now been identified in bacterial genomes.22,23 Approximately 25% of these homologues occur in putative chimeric proteins in which the Bhr sequence is connected to another functional domain,23 including the aforementioned Bhr-DGCs.

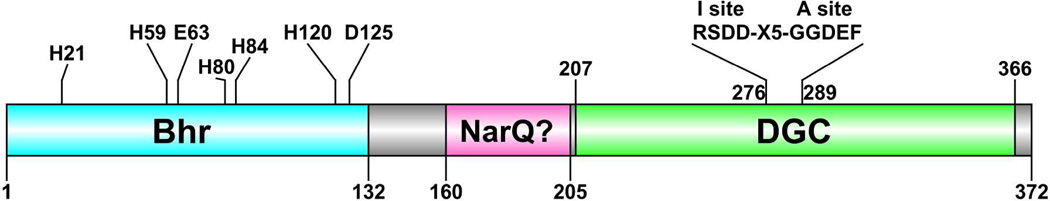

V. choleraeEL contains a gene (VC1216), encoding a chimeric Bhr-DGC, hereafter referred to as Vc Bhr-DGC. The domain structure inferred from the sequence is diagrammed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Annotated domains and sequence motifs for the 372-residue Vc Bhr-DGC encoded by VC1216. Predicted iron ligand residues are indicated in the Bhr domain. Predicted active (A site) and inhibitory (I site) sequence motifs are indicated in the DGC domain. NarQ? refers to provisional annotation as homologous to sequences in nitrate/nitrite sensor proteins. The residue-132 C-terminal limit of the Bhr domain is from Bailly et al.23 Sequence limits for the other domains are those listed at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/15641229?report=graph.

The seven predicted diiron ligand residues shown in Figure 1 are conserved in all known invertebrate Hrs and the vast majority of Bhr sequences.24,27,33,34 This conservation also extends to hydrophobic residues which line the O2 binding pocket in invertebrate Hrs. An in vivo connection of Vc Bhr-DGC to iron is supported by the observation that, among the ~40 V. choleraeEL genes encoding GGDEF domain proteins, VC1216 is the only one whose transcription was found to be down-regulated under iron-depleted growth conditions.35 VC1216 transcription was also found to be upregulated in response to increased c-di-GMP levels.36 An obvious inference from the diiron site and reversible O2 binding of invertebrate Hrs is that Bhr domains function as allosteric O2 or redox sensors. However, no full-length chimeric protein containing a Bhr domain has been isolated or characterized up to now. Here we report characterization of the full-length Vc Bhr-DGC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and General Procedures

Reagents and buffers were the highest grade commercially available. All reagents, protein, and media solutions were prepared using water purified with a Millipore ultrapurification system to a resistivity of 18 MΩ to minimize trace metal ion contamination. C-di-GMP was purchased from Axxora, LLC (Farmingdale, NY) and GTP from Epicentre® Biotechnologies (Madison, WI). An E. coli strain for expression of a His-tagged tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease S219V variant was obtained from Addgene, and the protease was expressed, isolated and purified as described in Supporting Information.

Cloning

The VC1216 gene was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA of V. choleraeEL and cloned into the NcoI/SalI sites of the plasmid, pAG8H (kindly provided by P. John Hart). pAG8H is derived from pkM26537,38 and encodes an N-terminal 8x-His tag followed by a TEV protease cleavage sequence. The residues added to the N-terminus of the expressed protein are: MDHHHHHHHHASENLYFQGA. (The pAG8H plasmid map is shown in Figure S1). The nucleotide sequence of the VC1216 gene in pAG8H was confirmed by sequencing at the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio Nucleic Acids Core Facility.

Protein Overexpression

pAG8H containing the VC1216 gene was heat-shock transformed into BL21(DE3)/pLysE and plated on Luria Bertani (LB)/agar containing 100 micrograms ampicillin (amp) and 35 micrograms chloramphenicol (Cm) per mL. Individual colonies were used to inoculate 100-mL LB/amp/Cm starter cultures, which were incubated overnight at 37 °C. The starter cultures were used to inoculate 1-L volumes of LB/amp/Cm, and these cultures were grown to an O.D. of 1.0 with shaking at 37 °C. The temperature of the cultures was then reduced to 23 °C, 100 mg FeSO4/L was added, and protein overexpression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactoside. The cultures were grown overnight at 23 °C and cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C. The cell paste was frozen and stored at −80 °C.

Protein isolation and purification

The buffer used for all protein isolation and purification steps was 50 mM MOPS, 0.25 M NaCl pH 7.3. Thawed cell paste were suspended in buffer and lysed by sonication on ice. Cell debris was removed was by centrifugation, and the overexpressed protein was purified by passing the supernatant over a 10-mL HisPure Cobalt Resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), washing the loaded column with buffer, then eluting with an imidazole gradient (0–250 mM imidazole in buffer). The purest fractions, as determined by 12% SDS-PAGE, were pooled and concentrated at 4 °C with a Millipore Ultrafree 15 concentrator with a 30-kDa cutoff. The purified protein was exchanged into 50 mM MOPS, 20% glycerol pH 7.3 using the same concentrator, then stored at −20 °C. In some preparations the 8x-His tag was removed from the purified Vc Bhr-DGC by incubation with His-tagged TEV protease (1 mg protease per 50 mg Vc Bhr-DGC) overnight at 4 °C in 50 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, 1 mM citrate, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol pH 7.5. The His-tagged TEV protease was then separated from the tag-free Vc Bhr-DGC using the HisPure cobalt column, as described above. The tag-free Vc Bhr-DGC, which eluted in the flow-through, was buffer exchanged as described above.

Reduction and Reoxidation of the Diiron Site in Vc Bhr-DGC

Anaerobic stock solutions of sodium dithionite in buffer were freshly prepared under an N2 atmosphere in an anaerobic glove box (Vacuum Atmospheres Co.). Anaerobic solutions of as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC at 150 µM (monomer basis) in 800 µl of 50 mM MOPS, 5% glycerol pH 7.3 were prepared in rubber septum/screw-capped quartz cuvettes (1-cm pathlength, Starna Scientific) by repeated cycles of evacuation and flushing of the headspace with N2 gas through a syringe needle connected to a vacuum line. Reduction of the Vc Bhr-DGC was achieved by addition of 1 equivalent of sodium dithionite from the concentrated stock solution via gas tight syringe. Autoxidation of the dithionite-reduced protein was achieved by repeated withdrawal and return of the solution between the cuvette and a pipette under an aerobic atmosphere.

DGC Activity Assays

DGC activity was determined by following the rate of production of c-di-GMP using an HPLC (Dionex Ultimate 3000). Either the as-isolated or dithionite-reduced protein in 250 µL of assay buffer (500 µM GTP, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 250 mM NaCl in 50 mM MOPS buffer pH 7.3 and 10% (v/v) glycerol) was incubated at 37 °C. Protein concentrations in the assay mixtures are listed in the Figure 8 legend.

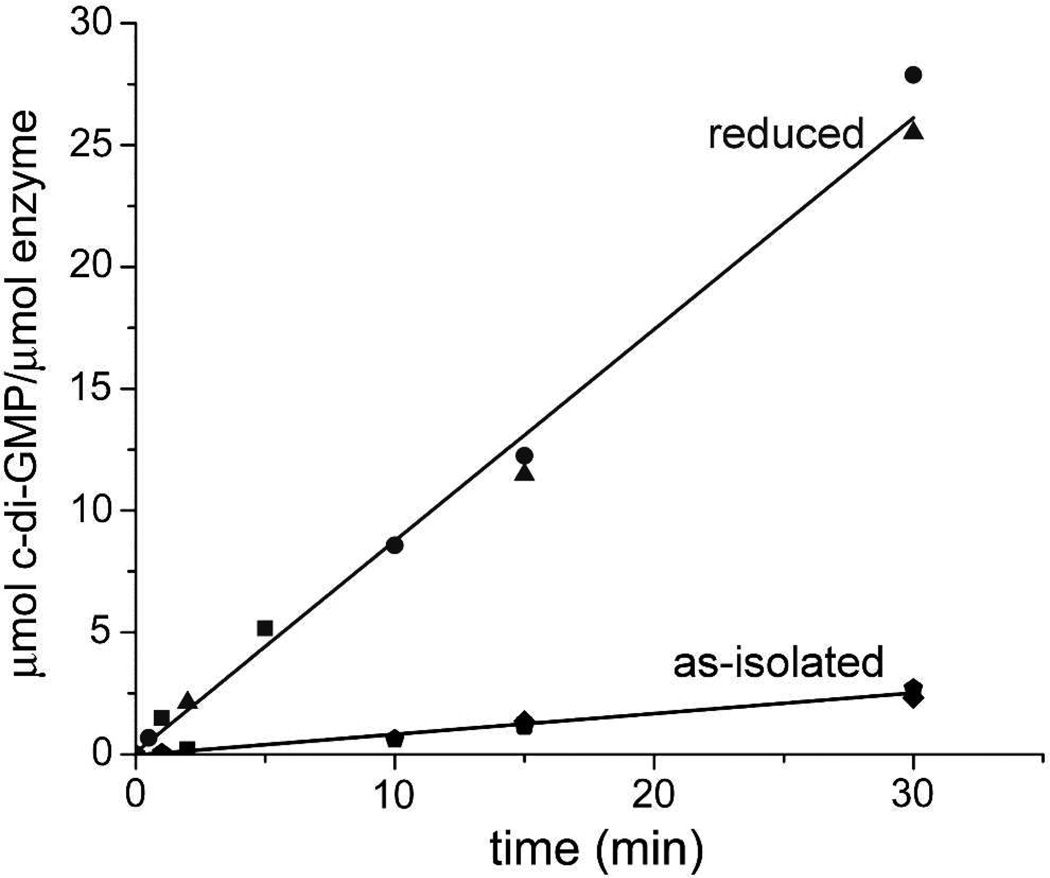

Figure 8.

Rates of c-di-GMP production for as-isolated and dithionite-reduced Vc Bhr-DGC. Assay conditions are described in Materials and Methods. Micromolar enzyme concentrations (protein monomer basis) are for reduced: 6.25 (circles), 10 (triangles), and 64 (squares); for as-isolated: 6.25 (diamonds), 74 (pentagons) and 100 (squares).

Fifty-microliter aliquots were removed periodically, and the enzyme was inactivated by heating the samples for 5 min at 100 °C. The samples were cooled on ice, and precipitates were removed by centrifugation. The supernatants were filtered through Spin-X UF concentrators with a 30-kDa nominal molecular weight cutoff (Corning). Ten to twenty microliters of the filtrates were injected onto a C18 analytical reverse phase HPLC column (Dionex) equilibrated with 92% 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 6.0 and 8% methanol (v/v) and eluted with solution having the same composition as used for equilibration. Eluted substrate and products were detected by absorbance at 254 nm and quantitated by peak areas calibrated to commercially available standards.

Assays of the reduced (diferrous) protein, prepared as described above, were carried out under anaerobic conditions. Two hundred microliters of a two-fold-concentrated assay buffer was made anaerobic under an N2 atmosphere in a rubber septum/screw-capped quartz cuvette. Two hundred microliters of the anaerobic reduced enzyme solution in 50 mM MOPS pH 7.3 + 5% glycerol was transferred via gas tight syringe to the anaerobic two-fold concentrated assay solution, incubated at 37 °C and analyzed as described above.

Native Protein Size and Homogeneity

Native protein molecular weights were determined using size exclusion chromatography on a Superose 6 10/30 column (GE Healthcare). The column was calibrated using protein standards (Sigma). Non-denaturing PAGE was conducted as for SDS-PAGE but without SDS and using 10 % gels.

UV/Vis Absorption Spectroscopy

UV−vis absorption spectra were recorded on an Ocean Optics USB 2000 spectrophotometer in screw-capped 1-cm pathlength quartz cuvettes containing an N2 atmosphere, when necessary.

Iron/Protein Mol Ratios

Protein concentrations were determined via the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Iron concentrations were determined via a standard ferrozine assay.39

Congo Red Plate Assay

Biofilm precursor formation in E. coli induced by Vc Bhr-DGC was determined using the Congo Red Plate assay.15 BL21(DE3)/pLysE cultures containing either the empty vector (pAG8H) or the vector with the inserted VC1216 were grown overnight at 37 °C in LB/amp/Cm. Congo red plates were prepared by adding 5 micrograms of Congo red, 100 micrograms amp, 35 micrograms Cm, and 0–1 mM IPTG to 20 mL of sterilized LB/agar. Five-microliter aliquots of the overnight cultures were spotted onto the plates, which were then incubated overnight at room temperature.

RESULTS

Homology Structural Modeling

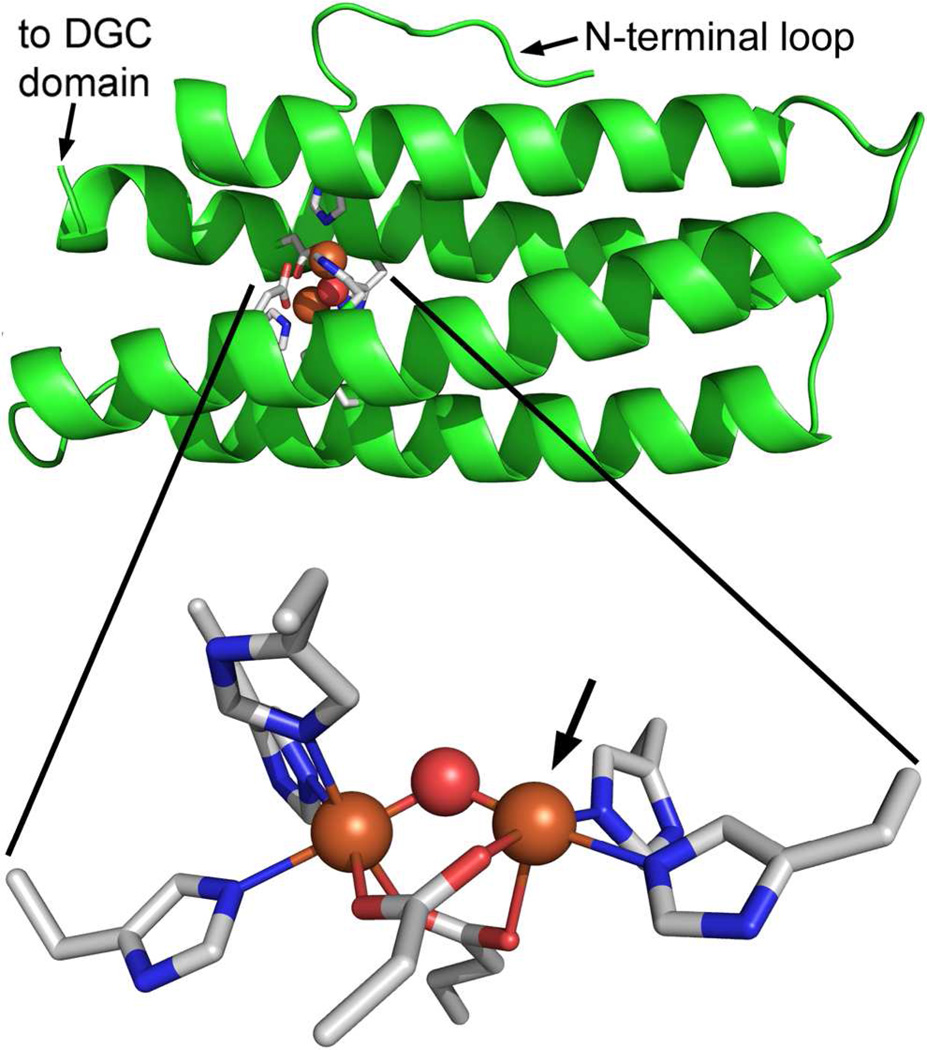

Figure 2 depicts a homology structural model of the Bhr domain of Vc Bhr-DGC (Vc Bhr) built using the SWISS-MODEL web server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/),40 when the Vc Bhr-DGC amino acid sequence was submitted. The server chose the DcrH-Hr azide adduct structure (PDB ID 2avk) as template. Since heteroatoms were not modeled by the server, the coordinates of the irons, bridging solvent and coordinated azide from the template structure were added to the modeled Vc Bhr coordinates. No further adjustments were made of any atomic coordinates in either the modeled Vc Bhr domain or the 2avk diiron site. The resulting Vc Bhr domain model, shown in Figure 2 and Figure S2, is essentially isostructural with that of DcrH-Hr, including positionings of the iron ligand residues. In invertebrate Hrs dioxygen binds end-on to the five-coordinate iron indicated by the arrow in Figure 2, and azide is known to bind to this iron in the diferric site of Hrs and Bhrs.24,27 Figure S2 depicts a view of the same Vc Bhr model highlighting the conserved hydrophobic pocket residues surrounding the coordinated azide atoms from the 2avk coordinates. Despite the fact that the iron, bridging solvent, and azide atoms were not included in the modeling of the Vc Bhr domain structure, no steric clashes were observed between these added heteroatoms and the modeled protein atoms. The SWISS-MODEL server also generated a structural model of residues 193–371 of Vc Bhr-DGC, which essentially comprises the annotated Vc DGC domain shown in Figure 1. This Vc DGC domain model, shown in Figure S3, was generated from the structure of another DGC, PleD.21. The SWISS-MODEL server did not return a model for residues 133–193, which lie between the Bhr and DGC domains shown in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Homology structural model of the Bhr domain (residues 3–133) in Vc Bhr-DGC generated using the DcrH-Hr diferric-azido structure (PDB entry 2avk) as template. The modeled protein backbone is shown in green cartoon mode, and modeled iron ligand side chains in CPK-colored stick mode. Iron atoms and bridging oxo from 2avk coordinates are shown as orange and red spheres, respectively. The azide atoms are omitted for clarity. Arrow indicates the azide coordination position. Images were generated in PyMOL (Delano Scientific LLC).

Physical, Spectroscopic and Redox Characterization of Vc Bhr-DGC

The overexpressed recombinant Vc Bhr-DGC containing an N-terminal His tag was isolated and purified from E. coli cell lysates by a standard one-step His-tag affinity column protocol. The spectroscopic properties and DGC activity of Vc Bhr-DGC (see below) were stable for several weeks in buffer containing 20% glycerol at −20 °C and for at least several hours during manipulations at room temperature. Results reported here are for protein solutions used within 24 hours of thawing and storage on ice. TEV protease cleavage of the N-terminal His tag did not affect stability, activity or oligomeric state of Vc Bhr-DGC. The results reported here are for the His-tagged protein. Vc Bhr-DGC migrated as a single homogeneous species in native PAGE gels (Figure S4), and as predominantly a homodimer on an analytical size exclusion column (~85 kDa vs ~45 kDa calculated for the His-tagged protein monomer, see Figure S5). Minor and variable portions of larger oligomeric species were also sometimes present. These higher molecular weight species did not show a single uniform size and are presumably artifacts, since their proportions tended to increase with increasing protein concentration, extended storage or in the absence of glycerol. The specific c-di-GMP activities of these higher molecular weight fractions were similar to that of the as-isolated homodimer, indicating that this oligomerization is not due to denaturation. Analyses of multiple preparations of purified Vc Bhr-DGC either with or without the His tag yielded 2.0 ± 0.2 iron/protein monomer, as expected for a diiron site in the Bhr domain. Based on the characterized proteins containing the GGDEF-X5-RXXD motif, no metal binding sites other than for Mg2+ are expected in the DGC domain.

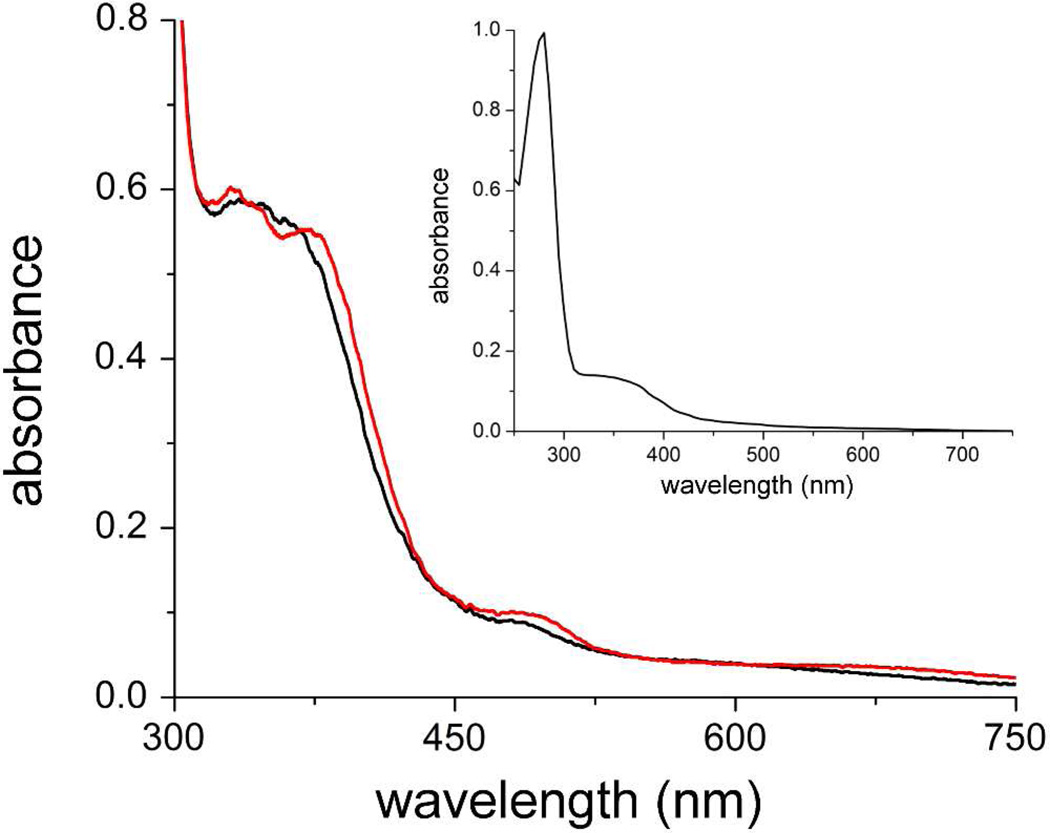

Figure 3 shows UV-vis absorption spectra of Vc Bhr-DGC. The relatively intense spectral features between 300 and 400 nm (ε335 nm = 6600 M−1cm−1 per diiron site) and weaker shoulder at ~490 nm are characteristic of the oxo/dicarboxylato-bridged diferric sites in Hrs and Bhrs shown in Figure 2.24,26 The small changes in spectral features following dialysis of the as-isolated protein to remove salt and imidazole are most likely to due removal of chloride, which is known to bind to diferric sites of Hr and Bhr proteins at the coordination position indicated by the arrow in Figure 2.27,41 Addition of excess phosphate, GTP or c-di-GMP did not affect the absorption spectra of the as-isolated protein. Despite the presence of the characteristic inhibitory site sequence motif (Figure 1), which tightly binds c-di-GMP in some other DGCs,13,16 the as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC contained no bound c-di-GMP, as monitored by either the absorption spectrum of the protein in the 250–280-nm region (Figure 3) or by HPLC analysis of washings from the heat-denatured protein. Solutions of as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC that had been incubated with excess c-di-GMP followed by dialysis against buffer also showed no retention of c-di-GMP by the protein.

Figure 3.

UV-vis absorption spectra of ~90 µM as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC in 250 mM NaCl 125 mM imidazole in 50 mM MOPS + 20% (v/v) glycerol pH 7.3 (red trace) or after dialysis against 50 mM MOP + 20% (v/v) glycerol pH 7.3 to remove NaCl and imidazole (black trace). Inset shows the spectrum of the dialyzed protein including the 280-nm region.

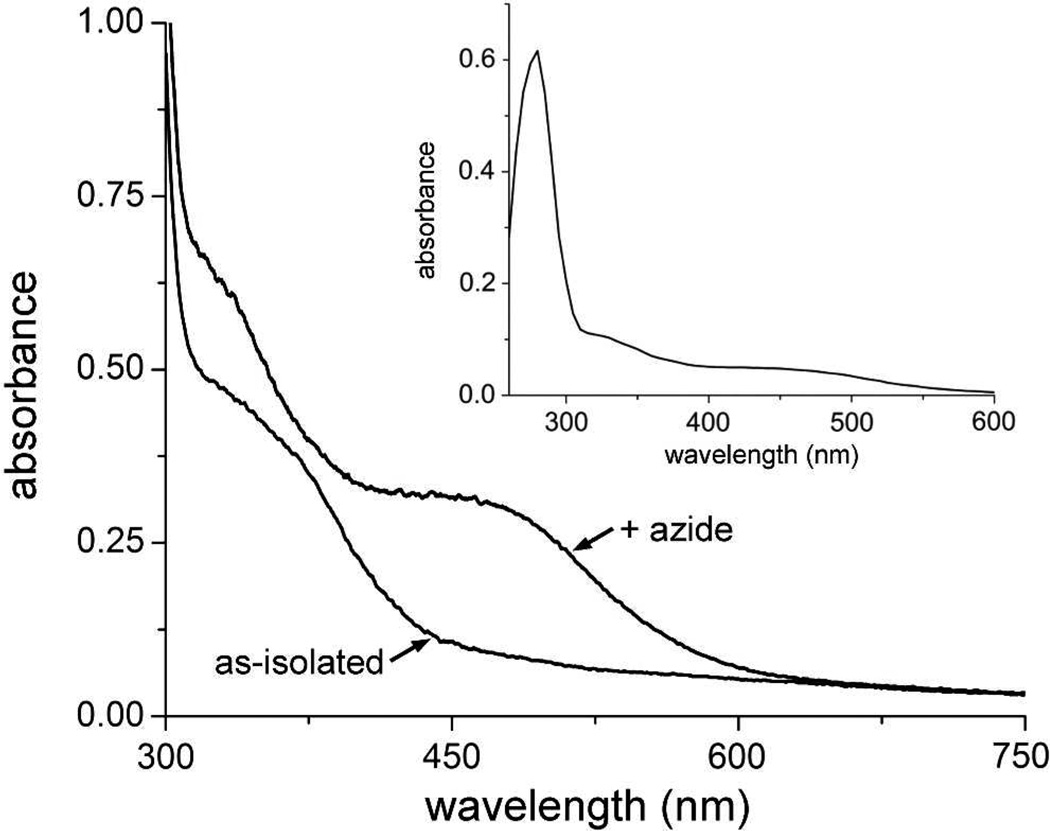

The absorption spectrum resulting from addition of excess azide to the as-isolated protein (Figure 4) closely resembles that of the azide adduct of diferric Hr and DcrH-Hr,26 in which azide binds end-on to the five-coordinate iron, as shown in Figure S2.27 This result demonstrates that the same iron to which O2 and azide bind in Hrs and Bhrs is accessible to coordination in the diiron site of Vc Bhr-DGC.

Figure 4.

UV-vis absorption spectra of as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC in 50 mM MOPS, 10% glycerol pH 7.3 and after addition of sodium azide to a final concentration of 50 mM. Inset shows the spectrum of the protein + azide including the 280 nm region. The azide-containing sample was incubated at 4 °C for 4 hours prior to recording the spectrum.

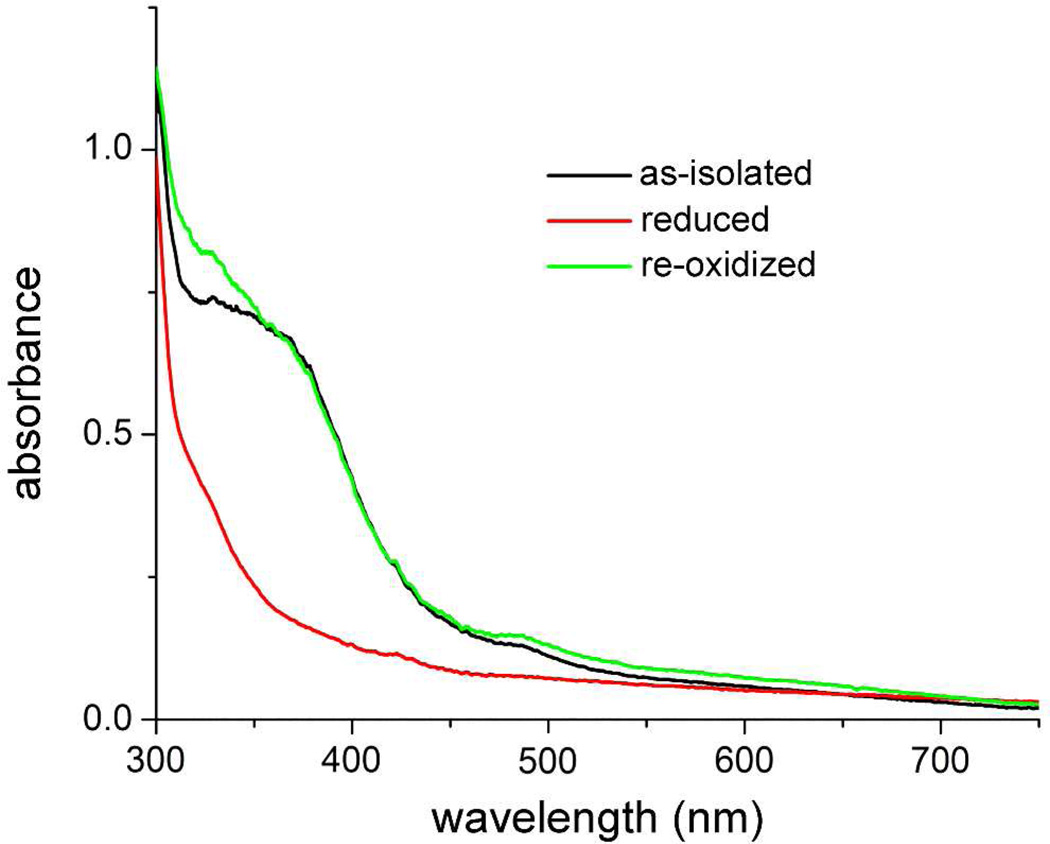

Figure 5 shows the absorption spectra resulting from redox cycling the diiron site in Vc Bhr-DGC. Reduction of the diferric to the diferrous site in the as-isolated protein with a slight excess of sodium dithionite was complete within ~3 hrs under anaerobic conditions at room temperature, as monitored by the decrease in absorbance at 350 nm. Autoxidation of the dithionite-reduced protein to the diferric form was rapid (< 1 min) upon manual mixing with air. The UV-vis absorption spectrum of the air-reoxidized protein (Figure 5) shows no indication of the characteristic O2 adduct of Hrs and Bhrs, which would be evident from its distinctive 500-nm absorption feature.24,26,28 The more weakly absorbing shoulder at ~490 nm together with the more intense features between 300 and 400 nm in Figure 5 is identical to that of the as-isolated protein in Figure 3 and, as noted above, is characteristic of diferric Hrs/Bhrs.

Figure 5.

UV-vis absorption spectra obtained upon redox cycling of Vc Bhr-DGC in 50 mM MOPS, 10% glycerol pH 7.3. A solution of the as-isolated protein (black trace) was reduced anaerobically with ~1 equivalent of sodium dithionite, then incubated for three hours anaerobically before recording the spectrum (red trace). This reduced sample was then re-oxidized by exposure to air, and the spectrum was recorded again (green trace).

DGC Activity of Vc Bhr-DGC

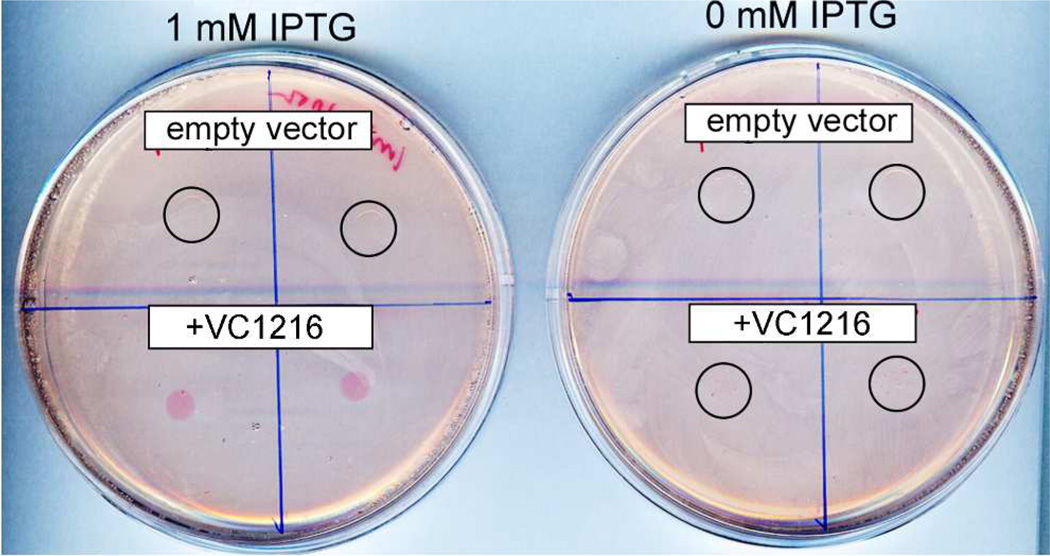

Figure 6 shows the results of a qualitative phenotypic assay for induction of cellulose production by c-di-GMP in E. coli.15 Cellulose production is a precursor to biofilm formation. The dye, Congo Red, binds to the cellulose coating on the plated bacterial colonies. The red-colored colonies thus indicate intracellular DGC activity. As shown in Figure 6, red colonies were observed only when the expression plasmid contained the Vc Bhr-DGC gene (VC1216), and only when expression of the gene was induced by IPTG in the agar. A magnified view of the image in Figure 6 (shown in Figure S6) also revealed some red spots within the two “0 mM IPTG”/+VC1216” colonies but no red spots in any of the “empty vector” colonies. This result demonstrates that Vc Bhr-DGC has intracellular DGC activity.

Figure 6.

Congo Red plate assay for DGC activity. Each quadrant of the LB/ampicillin/±IPTG agar plates was spotted with a 100-microliter aliquot of cultures of E. coli BL21(DE3) that had been transformed with either the parent expression plasmid, pAG8H, (upper two quadrants, labeled “empty vector”), or pAG8H containing the Vc Bhr-DGC gene (lower two quadrants, labeled “+VC1216”). The plates were then incubated for 72 hrs at 37 °C. Colonies showing no visible Congo Red stain in this view are circled. The circled colonies are better visualized in the magnified image (Figure S6).

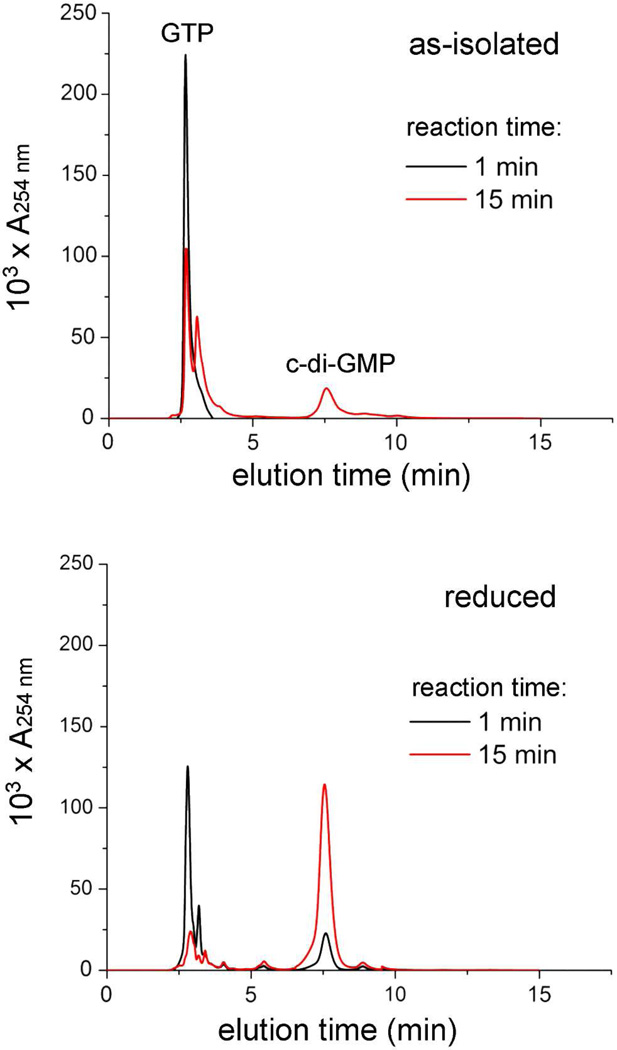

HPLC activity assays (Figure 7), conducted similarly to that described for other DGCs,16,18 showed that the as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC catalyzes consumption of GTP and simultaneous production of c-di-GMP, i.e., as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC has DGC activity. As-isolated fractions containing higher-molecular-weight oligomers showed no difference in specific activity. Addition of excess sodium azide (100 mM) to the as-isolated homodimeric Vc Bhr-DGC and incubation for 4 hrs at 4 °C prior to addition of the protein to the assay mixture (resulting in 12 mM azide in the assay mixture) had no effect on the activity compared to the as-isolated protein. The dithionite-reduced protein, assayed under anaerobic conditions showed a significantly higher DGC activity. Three sets of HPLC activity assays were conducted for both the as-isolated protein and the dithionite-reduced protein. The data are plotted in Figure 8. Linear regression analyses for the three data sets gave specific activities of 0.77 ± 0.01 for the reduced (diferrous) protein and 0.073 ± 0.007 µmol c-di-GMP/min-µmol enzyme (monomer basis) for the as-isolated (diferric) protein. The air-reoxidized protein reverted to the lower activity of the as-isolated protein. HPLC assays starting with c-di-GMP rather than GTP showed no evidence for c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity of the as-isolated protein.

Figure 7.

HPLC traces showing production of c-di-GMP and consumption of GTP. Assay and HPLC and conditions are described in Materials and Methods. The Vc Bhr-DGC concentrations were 74 µM and 64 µM (monomer basis) for the as-isolated and reduced proteins, respectively.

DISCUSSION

When considering the functional context of Bhr domains, we think it is important to distinguish Hrs/Bhrs from other protein sequences that have been included in the so-called “hemerythrin superfamily”.42–48 Inclusion of these other sequences is typically based on superficial structural homologies to other proteins that contain histidine/carboxylate-ligated non-heme diiron sites. Hr/Bhr diiron sites can be distinguished from these others by the following combination of structural features:22–25,27,28 i) the canonical seven-residue Hr/Bhr diiron binding sequence motif shown in Figure 1, ii) the residues lining the exogenous molecule binding pocket shown in Figure S2, and iii) the diiron coordination sphere shown in Figure 2, consisting of one six- and one five-coordinate iron center with a solvento/bis(1,3-carboxylato) bridging structure combined with five His as the only endogenous terminal ligands. This Hr/Bhr diiron site structure is the only type within the annotated “hemerythrin superfamily” that has been demonstrated to reversibly bind O2 (at the five-coordinate iron indicated by the arrow in Figure 2). Hr/Bhr sequences and diiron site structures are also distinct from those of the “ferritin superfamily”,49,50 which typically function in iron storage or as oxygenase/hydroxylases.

Vc Bhr-DGC is, to our knowledge, the first characterized example of a full-length chimeric protein containing a Bhr domain and the first demonstrated regulatory function for a Bhr domain. The as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC contains two tightly bound iron atoms per subunit and exhibits the spectroscopic and redox characteristics expected for oxo/dicarboxylato-bridged non-heme diiron sites. The specific DGC activities of Vc Bhr-DGC on an active site basis, 0.073 min−1 (as-isolated) or 0.77 min−1 (reduced), are within the range reported for some other DGCs.16,20,21 While we have not yet undertaken detailed kinetics studies, we presume the 500 µM GTP used in our activity assays is well above a saturating substrate level (as is the case for the other characterized DGCs). Under these conditions the most notable functional observation from our results is that Vc Bhr-DGC is ~10-times more active as a DGC when the Bhr domain is in the diferrous relative to the diferric form.

Our results are consistent with the previously proposed notion26,27 that any regulatory function of Bhr domains most likely originates from interactions of dioxygen or other exogenous redox active small molecules with the five-coordinate iron shown in Figure 2 and associated ferrous/ferric redox interconversions. The reactions of diferrous (deoxy) Hrs and Bhrs with O2 consist of reversible O2 binding to the deoxy form and autoxidative conversion of the O2-bound (oxy) form to the diferric (met) form. These two processes are typically formulated to occur consecutively according to equation 1:24

| (1) |

For invertebrate Hrs, the autoxidative conversion of the oxy to the met form is much slower than the reversible deoxy/oxy interconversion.24 For the characterized Bhrs, on the other hand, the oxy form has been found to be a transient intermediate between the deoxy and met forms.26,28,30 Based on the crystal structure of the Bhr domain of DcrH (DcrH-Hr), the more rapid autoxidation was attributed to a “substrate channel” not found in invertebrate Hrs, which promotes solvent access to the O2 binding pocket.27

In the case of Vc Bhr-DGC, autoxidation of the deoxy to the met form occurred essentially quantitatively within 1 minute of manual mixing the deoxy protein solution with air at room temperature. The putative oxy intermediate was not detected under these conditions.a Azide binding to the diferric site did not significantly affect DGC activity of the as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC, which indicates that exogenous small molecule binding to the diferric site is, by itself, not an allosteric trigger. These results implicate autoxidative diferrous/diferric (deoxy/met) redox interconversion as an allosteric regulatory trigger in Vc Bhr-DGC, as previously suggested for DcrH.27 Comparisons of the diferric and diferrous DcrH-Hr crystal structures led to the proposal that the diiron site redox changes are allosterically transmitted via changes in flexibility of the N-terminal loop in the Bhr domain. The Bhr domain of DcrH is at the C-terminal end of the full-length protein, whereas the Bhr domain of Vc Bhr-DGC is at the N-terminal end (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). In fact, there are several examples of both N- and C-terminal Bhr domains in putative Bhr-DGC chimeric proteins. While redox of cysteine residues could conceivably participate in allosteric transmission of redox changes, neither the Bhr domain nor the interdomain region (including NarQ? in Figure 1) of Vc Bhr-DGC contains any cysteine residues.

Vc Bhr-DGC was isolated predominantly as a homodimer, which is the minimum functional oligomer in the other characterized DGCs.13,15,16,18,21 The other known redox-regulated chimeric DGCs contain either heme or flavin-binding domains.17–20 The nature of the structural changes at the DGC domains that are allosterically induced by the heme or flavin redox changes has, to our knowledge, not been established. Our results also do not clarify this issue for Bhr domains. The SWISS-MODEL web server returned only disconnected Bhr and DGC domain models of Vc Bhr-DGC (Figure 2, Figure S2, and Figure S3). No structural model was returned for the relatively short NarQ? domain (Figure 1), which is provisionally annotated as homologous to sequences in nitrate/nitrite sensor proteins. Millimolar levels of nitrite or nitrate had little or no effect on DGC activity of the as-isolated Vc Bhr-DGC (data not shown).

V. cholerae cycles between the in vivo environment of its human host and ex vivo aquatic environments.6 Given our results, Vc Bhr-DGC could be significantly more active as a DGC in highly reducing or anaerobic environments and rapidly convert to a much less active form upon exposure to an aerobic environment. This behavior is consistent with a previous suggestion that Vc Bhr-DGC (VC1216) is involved in positively regulating biofilm formation in low-dioxygen environments.51 Bhr thus represents an alternative redox and/or diatomic gas-sensing regulatory domain for DGCs that uses a non-heme oxo/carboxylato-bridged diiron cofactor rather than flavin or heme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (D.M.K., Jr., GM040388 and (K.E.K., AI43486).

ABBREVIATIONS

- c-di-GMP

cyclic di-(3′,5′)-guanosine monophosphate

- V. choleraeET

Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. N16961

- Hr

invertebrate Hr

- Bhr

bacterial hemerythrin

- DGC

diguanylate cyclase

- Vc Bhr-DGC

V. choleraeET VC1216 protein containing Bhr and DGC domains

- Vc Bhr

Bhr domain from Vc Bhr-DGC

- DcrH

Desulfovibrio chemoreceptor protein H

- DcrH-Hr

Bhr domain protein derived from DcrH

- Amp

ampicillin

- Cm

chloramphenicol

- LB

Luria-Bertani

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside

Footnotes

ADDITIONAL NOTES

Rapid kinetics studies are in progress to detect a possible transient dioxygen adduct (Miner, K., Kurtz, D. M., Jr.).

Supporting Information

Procedure for isolation and purification of TEV protease, pAG8H plasmid map, Bhr domain model showing ligand binding pocket side chains, DGC domain model, images of SDS-PAGE and native PAGE gels, analytical size exclusion chromatogram, magnified image of Congo Red plate assay. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Romling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Dow JM. Cyclic di-GMP signaling in bacteria: recent advances and new puzzles. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:8327–8334. doi: 10.1128/JB.01079-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe AJ, Visick KL, editors. The second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sondermann H, Shikuma NJ, Yildiz FH. You've come a long way: c-di- GMP signaling. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012;15:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yildiz FH, Visick KL. Vibrio biofilms: so much the same yet so different. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waters CA, Lu WY, Rabinowitz JD, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:2527–2536. doi: 10.1128/JB.01756-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate regulates Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:5873–5882. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5873-5882.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim B, Beyhan S, Meir J, Yildiz FH. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;60:331–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamayo R, Schild S, Pratt JT, Camili A. Role of cyclic di-GMP during El tor biotype Vibrio cholerae infection: characterization of the in vivo-induced cyclic di- GMP phosphodiesterase CdpA. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:1617–1627. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01337-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seshasayee ASN, Fraser GM, Luscombe NM. Comparative genomics of cyclic-di-GMP signalling in bacteria: post-translational regulation and catalytic activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5970–5981. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D, Hunt JF, Schirmer T. Making, breaking, and sensing of cyclic-di- GMP: structural, thermodynamic and evolutionary principles. In: Wolfe AJ, Visick KL, editors. The second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2010. pp. 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levi A, Folcher M, Jenal U, Shuman HA. Cyclic diguanylate signaling proteins control intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila. MBio. 2011;2:e00316–e00310. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00316-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De N, Pirruccello M, Krasteva PV, Bae N, Raghavan RV, Sondermann H. Phosphorylation-independent regulation of the diguanylate cyclase WspR. PLos Biol. 2008;6:601–617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De N, Navarro MVAS, Raghavan RV, Sondermann H. Determinants for the activation and autoinhibition of the diguanylate cyclase response regulator WspR. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;393:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuckerman JR, Gonzalez G, Sousa EHS, Wan XH, Saito JA, Alam M, Gilles-Gonzalez MA. An oxygen-sensing diguanylate cyclase and phosphodiesterase couple for c-di-GMP control. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9764–9774. doi: 10.1021/bi901409g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi YN, Rao F, Luo Z, Liang ZX. A flavin cofactor-binding PAS domain regulates c-di-GMP synthesis in AxDGC2 from Acetobacter xylinum. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10275–10285. doi: 10.1021/bi901121w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawai H, Yoshioka S, Uchida T, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Ishimori K, Aono S. Molecular oxygen regulates the enzymatic activity of a heme-containing diguanylate cyclase (HemDGC) for the synthesis of cyclic di-GMP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitanishi K, Kobayashi K, Kawamura Y, Ishigami I, Ogura T, Nakajima K, Igarashi J, Tanaka A, Shimizu T. Important roles of Tyr43 at the putative heme distal side in the oxygen recognition and stability of the Fe(II)-O2 complex of YddV, a globin-coupled heme-based oxygen sensor diguanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10381–10393. doi: 10.1021/bi100733q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wassmann P, Chan C, Paul R, Beck A, Heerklotz H, Jenal U, Schirmer T. Structure of BeF3 −-modified response regulator PleD: Implications for diguanylate cyclase activation, catalysis, and feedback inhibition. Structure. 2007;15:915–927. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.French CE, Bell JML, Ward FB. Diversity and distribution of hemerythrin-like proteins in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;279:131–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailly X, Vanin S, Chabasse C, Mizuguchi K, Vinogradov SN. A phylogenomic profile of hemerythrins, the nonheme diiron binding respiratory proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurtz DM., Jr . Dioxygen-binding proteins. In: McCleverty JA, Meyer TJ, editors. Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II. Oxford, U.K.: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 229–260. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanin S, Negrisolo E, Bailly X, Bubacco L, Beltramini M, Salvato B. Molecular evolution and phylogeny of sipunculan hemerythrins. J. Mol. Evol. 2006;62:32–41. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong J, Kurtz DM, Jr, Ai J, Sanders-Loehr J. A hemerythrin-like domain in a bacterial chemotaxis protein. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5117–5125. doi: 10.1021/bi992796o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isaza CE, Silaghi-Dumitrescu R, Iyer RB, Kurtz DM, J R, Chan MK. Structural basis for O2 sensing by the hemerythrin-like domain of a bacterial chemotaxis protein: Substrate tunnel and fluxional N terminus. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9023–9031. doi: 10.1021/bi0607812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onoda A, Okamoto Y, Sugimoto H, Shiro Y, Hayashi T. Crystal structure and spectroscopic studies of a stable mixed-valent state of the hemerythrin-like domain of a bacterial chemotaxis protein. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:4892–4899. doi: 10.1021/ic2001267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou S, Saw JH, Lee KS, Freitas TA, Belisle C, Kawarabayasi Y, Donachie SP, Pikina A, Galperin MY, Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Omelchenko MV, Sorokin A, Wolf YI, Li QX, Keum YS, Campbell S, Denery J, Aizawa S, Shibata S, Malahoff A, Alam M. Genome sequence of the deep-sea gamma-proteobacterium Idiomarina loihiensis reveals amino acid fermentation as a source of carbon and energy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:18036–16041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407638102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kao WC, Wang VCC, Huang YC, Yu SSF, Chang TC, Chan SI. Isolation, purification and characterization of hemerythrin from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:1607–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlsen OA, Ramsevik L, Bruseth LJ, Larsen O, Brenner A, Berven FS, Jensen HB, Lillehaug JR. Characterization of a prokaryotic haemerythrin from the methanotrophic bacterium Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) FEBS J. 2005;272:2428–2440. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen KHC, Wu HH, Ke SF, Rao YT, Tu CM, Chen YP, Kuei KH, Chen YS, Wang VCC, Kao WC, Chan SI. Bacteriohemerythrin bolsters the activity of the particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) in Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath) J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;111:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiong J, Phillips RS, Kurtz DM, Jr, Jin S, Ai J, Sanders-Loehr J. The O2 binding pocket of myohemerythrin: role of a conserved leucine. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8526–8536. doi: 10.1021/bi9929397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farmer CS, Kurtz DM, Jr, Phillips RS, Ai J, Sanders-Loehr J. A leucine residue ‘gates’ solvent but not O2 access to the binding pocket of Phascolopsis gouldii hemerythrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:17043–17050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mey AR, Wyckoff EE, Kanukurthy V, Fisher CR, Payne SM. Iron and fur regulation in Vibrio cholerae and the role of Fur in virulence. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:8167–8178. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8167-8178.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beyhan S, Tischler AD, Camilli A, Yildiz FH. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:3600–3613. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3600-3613.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melcher K. Errata to: "A modular set of prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression vectors,". Anal. Biochem. 2000;282:266–266. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4383. (vol 277, pg 109, 2000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melcher K. A modular set of prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression vectors. Anal. Biochem. 2000;277:109–120. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stookey LL. Ferrozine - a new spectrophotometric reagent for iron. Anal. Chem. 1970;42:779–781. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farmer CS, Kurtz DM, Jr, Liu ZJ, Wang BC, Rose J, Ai J, Sanders-Loehr J. The crystal structures of Phascolopsis gouldii wild type and L98Y methemerythrins: structural and functional alterations of the O2 binding pocket. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2001;6:418–429. doi: 10.1007/s007750100218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strube K, de Vries S, Cramm R. Formation of a dinitrosyl iron complex by NorA, a nitric oxide-binding di-iron protein from Ralstonia eutropha H16. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:20292–20300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Justino M, Baptista J, Saraiva L. Di-iron proteins of the Ric family are involved in iron-sulfur cluster repair. Biometals. 2009;22:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vashisht AA, Zumbrennen KB, Huang XH, Powers DN, Durazo A, Sun DH, Bhaskaran N, Persson A, Uhlen M, Sangfelt O, Spruck C, Leibold EA, Wohlschlegel JA. Control of iron homeostasis by an iron-regulated ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2009;326:718–721. doi: 10.1126/science.1176333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salahudeen AA, Thompson JW, Ruiz JC, Ma HW, Kinch LN, Li QM, Grishin NV, Bruick RK. An E3 ligase possessing an iron-responsive hemerythrin domain is a regulator of iron homeostasis. Science. 2009;326:722–726. doi: 10.1126/science.1176326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padmaja N, Rajaram H, Apte SK. A novel hemerythrin DNase from the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp strain PCC7120. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;505:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Traverso ME, Subramanian P, Davydov R, Hoffman BM, Stemmler TL, Rosenzweig AC. Identification of a hemerythrin-like domain in a P-1B-type transport ATPase. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7060–7068. doi: 10.1021/bi100866b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson JW, Salahudeen AA, Chollangi S, Ruiz JC, Brautigam CA, Makris TM, Lipscomb JD, Tomchick DR, Bruick RK. Structural and molecular characterization of iron-sensing hemerythrin-like domain within F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 5 (FBXL5) J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:7357–7365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrews SC. The ferritin-like superfamily: evolution of the biological iron storeman from a rubrerythrin-like ancestor. Bba-Gen Subjects. 2010;1800:691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundin D, Poole AM, Sjoberg BM, Hogbom M. Use of structural phylogenetic networks for classification of the ferritin-like superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:20565–20575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.367458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karatan E, Duncan TR, Watnick PI. NspS, a predicted polyamine sensor, mediates activation of Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation by norspermidine. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7434–7443. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7434-7443.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.