Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to summarize recent literature on approaches to supporting healthy coping in diabetes, in two specific areas: 1) impact of different approaches to diabetes treatment on healthy coping; and 2) effectiveness of interventions specifically designed to support healthy coping.

Methods

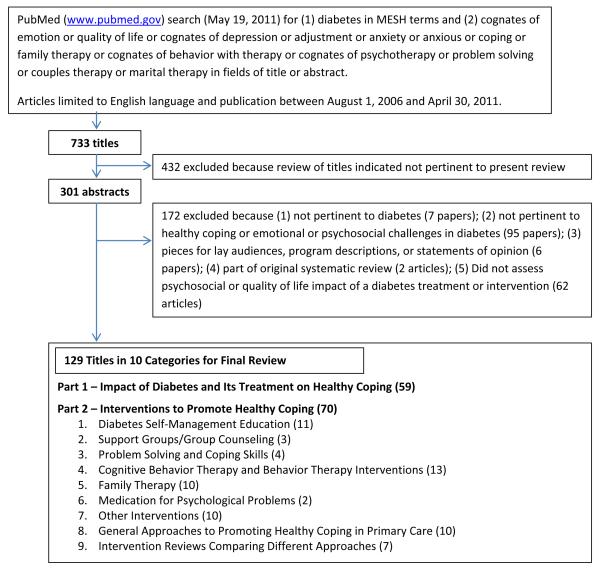

A PubMed search identified 129 articles published August 1, 2006 – April 30, 2011, addressing diabetes in relation to emotion, quality of life, depression, adjustment, anxiety, coping, family therapy, behavior therapy, psychotherapy, problem-solving, couples therapy, or marital therapy.

Results

Evidence suggests that treatment choice may significantly influence quality of life, with treatment intensification in response to poor metabolic control often improving quality of life. The recent literature provides support for a variety of healthy coping interventions in diverse populations, including diabetes self-management education, support groups, problem-solving approaches, and coping skills interventions for improving a range of outcomes, Cognitive Behavior Therapy and collaborative care for treating depression, and family therapy for improving coping in youths.

Conclusions

Healthy coping in diabetes has received substantial attention in the past five years. A variety of approaches show positive results. Research is needed to compare effectiveness of different approaches in different populations and determine how to overcome barriers to intervention dissemination and implementation.

In recognition of the wide range of coping challenges presented by diabetes across genetic, behavioral, family, social, community, organizational, and political contexts, the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) has identified healthy coping as one of the key AADE7™ Self-care Behaviors and defined it as the following:

“Health status and quality of life are affected by psychological and social factors. Psychological distress directly affects health and indirectly influences a person’s motivation to keep their diabetes in control. When motivation is dampened, the commitments required for effective self-care are difficult to maintain. When barriers seem insurmountable, good intentions alone cannot sustain the behavior. Coping becomes difficult and a person’s ability to self-manage their diabetes deteriorates.”

From this definition, it is clear that the construct of “healthy coping” includes a number of related but distinct domains of psychosocial outcomes. In addition to avoiding specific psychological problems such as depressive and anxiety disorders, high levels of perceived stress and other negative emotions, and diabetes-specific distress, healthy coping also involves positive attitudes toward diabetes and its treatment, positive relationships with others, and high perceived health-related quality of life (QOL). That is, healthy coping extends beyond the mere avoidance of psychiatric morbidity to encompass high levels of psychosocial functioning and a positive outlook on the illness and overall quality of life. Table 1 provides more detail on specific healthy coping domains that are commonly examined in the diabetes literature.

Table 1. Domains of healthy coping.

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| Depression | Disorder of mood characterized by feelings of sadness or emptiness, reduced interest in activities, sleep disturbances, loss of energy, difficulty concentrating or making decisions83 |

| Anxiety disorder | Disorders characterized by abnormal or inappropriate symptoms of anxiety (e.g., increased heart rate, tensed muscles, intense worry), such as generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder83 |

| Perceived stress | Degree to which individuals perceived different aspects of their lives as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming84 |

| Diabetes-specific distress | Negative emotional responses and perceived burden related to diabetes85, 86 |

| Positive attitudes and beliefs about the illness and treatment |

Psychological adjustment to diabetes;87 treatment satisfaction;88 |

| Positive relationships with others | High perceptions of general and diabetes-specific social support; family functioning |

| Health-related quality of life | Subjective evaluation of overall physical, mental, and social health and functioning |

As awareness of the inter-relationships between diabetes, its management, and these outcomes has grown, interest in intervening to facilitate healthy coping in diabetes patients has also expanded. The purpose of this paper is to systematically review literature on healthy coping in diabetes published in the past five years, with a focus on identifying evidence for effective interventions that has emerged since a prior review 1. Two questions within this broad topic area are addressed: 1) What are the effects of different diabetes treatment approaches on healthy coping outcomes? 2) What is the effect of different interventions designed to improve healthy coping on psychosocial and quality of life outcomes?

Methods

Search

Parallel with the multiple domains of healthy coping, intervention approaches for addressing these concerns in diabetes patients across the lifespan are diverse, and there are relatively few well-controlled studies of any single intervention approach. Thus, this review was designed to provide a broad appraisal of promising approaches for addressing an array of healthy coping issues. The review used systematic review procedures in specifying the terms and approach to searching for and abstracting data from articles, but narrative procedures in including articles without a priori criteria based on methods and design.

A PubMed search of the English-language literature published between August 1, 2006 and April 30, 2011 was performed. Combinations of diabetes with the terms emotion, quality of life, depression, adjustment, anxiety, anxious, coping, family therapy, behavior therapy, psychotherapy, problem solving, couples therapy, or marital therapy were used to identify relevant studies. Figure 1 provides details on search procedures and results.

Figure 1. Outline of Search of Healthy Coping in Diabetes Management, 2006 to 2011.

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts of articles meeting the above search criteria were reviewed as candidates for data abstraction. To be included in the final review, articles needed to report the effects of either a diabetes treatment or healthy coping intervention on at least one psychosocial and/or quality of life outcome. Retrospective and prospective studies were included, along with narrative or systematic review articles. All articles pertaining to T1DM or T2DM were included and there were no restrictions with regard to patient age. Articles aimed at lay audiences, statements of opinion, or descriptions of programs with no research component were excluded.

Data Abstraction

Articles meeting criteria were grouped into the two main questions targeted for review: 1) evidence describing the impact of diabetes treatments on healthy coping constructs; and 2) interventions to promote healthy coping. Articles were then further categorized according to intervention type (see Figure 1), abstracted independently by the authors, and incorporated into the Healthy Coping Evidence Table (available as an online Appendix). Abstracted data elements included study design, original research versus review of published studies, study objectives, sample size, healthy coping outcomes assessed, other outcomes assessed (e.g., HbA1c), and principal findings, including both significant and non-significant results. For all studies, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ (AACE) evidence ratings2 corresponding to their study designs were also determined.

Study Characteristics

As shown in Figure 1, 129 articles met criteria for inclusion, including 59 articles examining the effect of diabetes treatments on healthy coping domains and 70 articles examining the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions specifically designed to promote healthy coping. Cognitive behavior therapy, family therapy, diabetes self-management education, and primary care-based approaches were the most common intervention types; fewer articles were identified which focused on problem solving and coping skills, support groups or group counseling, and medication for psychological problems.

Data Synthesis

The evidence table describing studies within the two broad areas relevant to healthy coping in diabetes drove the organization of the narrative review accordingly: 1) effect of diabetes treatments on QOL and psychosocial outcomes; 2) evidence for the efficacy or effectiveness of healthy coping interventions in improving QOL and other psychosocial outcomes. Results summarized in the text below focus on articles reporting original research, with Tables 2 and 3 providing additional detail in two areas. Table 2 summarizes the large number of studies that examined the psychosocial and quality of life impacts of different methods of intensifying treatment in poorly controlled diabetes, while Table 3 summarizes original intervention research studies identified in the review. The complete Healthy Coping Evidence Table is available as an online Appendix.

Table 2. Key studies on the effects of treatment intensification with different types of therapies and regimens in adults with type 2 diabetes.

| Reference | Study Objectives and Methods |

Study Design | Sample Size | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best et al 2011(Best et al., 2011) | Compare once-weekly injections with exenatide to two different classes of OHAs (sitagliptin or pioglitazone) with regard to effects on QOL and psychological and clinical outcomes |

Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter clinical trial; poorly controlled adults with type 2 diabetes on metformin randomized to exenatide GLP-4 injectible) once weekly plus placebo oral capsule each morning, sitagliptin plus placebo once weekly injection, or pioglitazone plus placebo once weekly injection |

N = 491 | Addition of any of the three medications improved QOL and psychological outcomes. Greater improvements in weight-related QOL, general health utility, and treatment satisfaction were observed for exenatide once-weekly compared to one or both of the other treatments. |

| Peyrot et al 2008(Peyrot et al., 2008) | Compare diabetes-related distress and clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients using insulin with or without meal-time pramlintide (an amylin analog) |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study; type 2 patients using insulin glargine with or without OHAs were randomized to pramlintide or placebo |

N = 211 | Pramlintide use resulted in decreases in total diabetesrelated distress and regimen-related distress in those who were highly distressed at baseline. |

| Peyrot et al 2010(Peyrot et al., 2010) | Assess effect of adding mealtime pramlintide or rapid-acting insulin analog RAIA) to basal insulin therapy in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes |

Open-label, randomized, parallel group trial, stratified with regard to use of basal insulin prior to study enrollment |

N = 112 | Adding either pramlintide or RAIA at mealtime to basal insulin improved treatment satisfaction. Pramalintide also reduced diabetes distress and improved sleep quality, weight control, and appetite control; RAIA improved eating flexibility and perceived weight control. |

| Bode et al 2010(Bode et al., 2010) | Compare effect of adding a GLP-1 once daily medication (liraglutide) versus an OHA (glimepiride) to treatment regimen |

Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallelgroup, multi-center clinical trial; patients stratified by initial treatment with a single OHA vs. diet and exercise only and randomized to once-daily treatment with once-daily liraglutide (GLP- 1) 1.2 mg or 1.8 mg or glimepiride (sulfonylurea) |

N = 732 | Liraglutide produced more favorable improvements in health-related QOL and weight concerns compared to glimepiride, with much stronger effects at the higher dosage of 1.8 mg |

| Ushakova et al 2007(Ushakova et al., 2007) |

Compare glycemic control, weight gain, tolerability, and treatment satisfaction and QOL for 3 different regimens in insulin-naïve uncontrolled type 2 diabetes patients: 1) biphasic insulin aspart 30 alone, 2) biphasic insulin aspart 30 + metformin, and 3) OHA therapy alone |

Randomized, open-label, parallel-group, multicenter trial |

N = 308 | The insulin regimens improved QOL and treatment satisfaction similarly to a multiple drug oral regimen. |

| Lingvay et al 2009(Lingvay et al., 2009) | Compare triple therapy with OHA (metformin, pioglitazone, and glyburide) to twice-daily insulin plus metformin in newly diagnosed, adult type 2 diabetes patients. |

Open-label, randomized controlled trial |

N = 29 | There were no group differences in hypoglycemic events, weight gain, adherence, or changes in QOL, and social worries improved over time in both groups. All patients assigned to insulin reported satisfaction with insulin treatment and willingness to continue at 18 months follow-up. |

| Houlden et al 2007(Houlden et al., 2007) |

Assess effect of insulin glargine (basal insulin) initiation with no change in OHA therapy versus optimization of OHA therapy on QOL |

Randomized, controlled trial of adults aged 18-80 with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glucose control taking 0, 1, or two OHAs |

N = 366 | Addition of insulin glargine versus more OHAs had greater positive impact on treatment satisfaction and QOL. |

| Vinik et al 2007(Vinik & Zhang, 2007) | Compare effect of add-on insulin glargine versus rosiglitazone on healthrelated QOL in patients with type 2 diabetes already taking a sulfonylurea plus metformin |

24-week, multicenter, randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial |

N = 217 | Symptom distress, mood symptoms, ophthalmologic distress, fatigue distress, and general self-rated health improved more for the insulin glargine group. Adverse events were also less frequent in the insulin glargine group. |

Table 3. Summaries of Key Intervention Articles.

| Reference | Study Objectives and Methods | Study Design | Sample Size |

Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Self-Management Education | ||||

| Speight et al 2010(Speight et al., 2010) | Evaluate long-term (44-month follow-up) outcomes of Dose Adjustment for Normal Eating DAFNE), a structured education program in intensive insulin therapy for adults with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes |

Observational cohort study of all participants who were originally randomized to receive DAFNE immediately versus after a 6-month waitlist |

N = 104 | Improvements in QOL seen at 12 months follow-up were sustained at 44-months follow-up. Improvements in treatment satisfaction at 12-months followup decreased significantly at 44 months, but remained meaningfully higher than baseline levels. |

| Kempf et al 2010(Kempf et al., 2010) | Evaluate ROSSO-in-praxi, a structured 12-week motivation and education program focused on self-monitoring of blood glucose in 405 adults with type 2 diabetes |

Pre-post within-group comparison |

N = 405 | Mental health and depressive symptoms improved from preintervention to post-intervention. |

| Rossi et al 2010(Rossi et al., 2010) | Compare use of a Diabetes Interactive Diary (DID) to a structured carbohydrate counting education program |

Open-label, international, multicenter, randomized parallel-group trial; adults with type 1 diabetes were randomly assigned to DID versus carbohydrate counting education |

N = 130 | The DID group experienced greater improvements in treatment satisfaction and QOL, including greater dietary freedom, and duration of education required was also lower. |

| Bendik et al 2009(Bendik et al., 2009) | Evaluate training in flexible insulin therapy on psychological and metabolic outcomes in type 1 diabetes patients; intervention consisted of 7 weekly group sessions |

Pre-post within-group comparison of type 1 diabetes patients |

N = 45 | QOL, self-control, and diabetes knowledge all improved significantly. |

| Utz et al 2008(Utz et al., 2008) | Compare group versus individual culturally-tailored diabetes selfmanagement education in rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes |

Randomized trial; patients assigned to group or individual DSME/T |

N = 22 | There was a non-significant trend for greater improvements in empowerment, goal attainment, diet, and foot care for Group DSME/T. Both group and individual DSME/T improved goal attainment and self-care. |

| Lowe et al 2008(Lowe et al., 2008) | Evaluate intensive insulin management to help type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients match insulin dose to carbohydrate intake |

Pre-post within-group comparison; patients with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes assessed at 4- monhts and 12-months |

N = 137 | The program improved diabetesrelated QOL and problem-solving skills. |

| Nansel et al 2007(Nansel et al., 2007) | Assess outcomes of a diabetes self-management education utilizing a “diabetes personal trainer” (i.e., trained nonprofessionals) in youth with type 1 diabetes |

Randomized, controlled trial; adolescents with type 1 diabetes assigned to personal trainer intervention or usual care |

N = 81 | There was no significant effect of the personal trainer intervention on QOL or adherence. |

| Tang et al 2010(Tang et al., 2010) | Evaluate a empowerment-based diabetes self-management support intervention delivered in a weekly group format |

Control-intervention time series design; African Americans with type 2 diabetes first participated in a 6-month control period with weekly educational newsletters and then 6-month intervention |

N = 77 | No effect of the intervention was observed for diabetes-specific QOL, empowerment, or adherence. |

| Bastiaens et al 2009(Bastiaens et al., 2009) | Implement and evaluate a group self-management education program in primary care for adults with type 2 diabetes |

Pilot study; pre-post within-group comparison |

N = 44 | Diabetes-related emotional distress was reduced at 12- months post-intervention, but this improvement was not sustained at 18-month follow-up. |

| Support Groups and Group Counseling | ||||

| Chaveepojnkamjorn et al 2009(Chaveepojnkamjorn et al., 2009) |

Evaluate a 16-week self-help group program for adults with type 2 diabetes; intervention focused on building good relationships, diabetes self-management knowledge and skill, selfmonitoring, motivation in self-care, sharing experiences among group members, and improvement of training skills for group leaders as well as group structure. |

Multicenter randomized, controlled trial; adult patients at 7 health care centers in Thailand assigned to self-help group program or control group receiving diabetes services |

N = 146 | All four domains of QOL that were assessed (physical health, psychological, social relationships, and environment) improved in the self-help group compared to the control group at 12-week and 24-week follow-up. |

| Heisler et al 2010(Heisler et al., 2010) | Compare a reciprocal peersupport RPS) program with supplemental group sessions to nurse case management (NCM) plus 1.5 hour-education session in older male veterans with poorly controlled diabetes |

Randomized controlled trial; patients assigned to RPS or NCM |

N = 244 | Perceived diabetes social support improved significantly more in the RPS group compared to NCM, and more RPS patients initiated insulin therapy. No significant differences in diabetes-specific distress. |

| Comellas et al 2010(Comellas et al., 2010) | Evaluate peer-led community discussion circles integrating selfmanagement support with discussion of information and skills through storytelling and exercises |

Pre-post within-group comparison of urban, minority adults with diabetes |

N = 17 | Improved some aspects of wellbeing, including feeling more active and vigorous at program completion. |

| Problem-Solving and Coping Skills | ||||

| Amoako et al 2008(Amoako & Skelly, 2007; Amoako et al., 2008) |

Evaluate a 4-week problemsolving and cognitive reframing telephone intervention in older African American women with diabetes |

Randomized, controlled trial; older African American assigned to the intervention or usual care |

N = 68 | The intervention increased participation in exercise, psychosocial adjustment, problem-solving, and uncertainty compared to usual care. |

| Gregg et al 2007(Gregg et al., 2007) | Compare acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a coping skills intervention plus diabetes education to diabetes education alone |

Randomized, controlled trial; adults with type 2 diabetes assigned to ACT plus education or education alone |

N = 81 | After 3 months, the ACT group showed increased use of acceptance and mindfulness coping strategies and improved diabetes self-care. Changes in acceptance coping and self-care mediated the effect of ACT on glycemic control. |

| Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (CBT) and Behavior Therapy | ||||

| Van Bastelaar et al 2011 (van Bastelaar et al., 2011) |

Evaluate a web-based CBT intervention for adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes |

Randomized controlled trial; adult patients with elevated depressive symptoms assigned to web-based intervention or wait-list control |

N = 255 | The web-based CBT intervention group experienced greater reductions in depressive symptoms and diabetes-specific emotional distress. |

| Ismail et al 2010(Ismail et al., 2010) | Compare effects of motivational enhancement therapy (MET) plus CBT to MET alone and usual care |

Three-arm parallel randomized controlled trial of adults with inadequately controlled diabetes |

N = 344 | There was no significant effect of either MET plus CBT or MET alone compared to usual care on depression or QOL. |

| Lehmkuhl et al 2010(Lehmkuhl et al., 2010) | Evaluate a Telehealth Behavioral Therapy (TBT) for youths with type 1 diabetes and a parent/caregiver |

Randomized controlled trial; child-parent dyads randomized to 12-week TBT or waitlist control |

N = 32 | Youth perception of unsupportive behaviors increased and perception of caring parental behaviors decreased in the TBT vs. control group. |

| Amsberg et al 2009(Amsberg et al., 2009) | Evaluate CBT intervention delivered in a combined group/individual format |

Randomized controlled trial; adults with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes assigned to intervention or control group |

N = 94 | The CBT group experienced greater improvements in wellbeing, diabetes-related distress, perceived stress, anxiety, and depression. |

| Snoek et al 2008(Snoek et al., 2008) | Compare CBT delivered in a group format to blood-glucose awareness training (BGAT) in adults with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes, and examine whether effects varied by baseline depression |

Randomized trial; adults assigned to CBT or BGAT |

N = 86 | Both CBT and BGAT improved depressive symptoms at 12- month follow-up. |

| Salamon et al 2010(Salamon et al., 2010) | Evaluate a 1-hour CBT-based intervention with 3 weekly followup phone calls in adolescents with type 1 diabetes; intervention focused on cognitive restructuring and problem-solving training |

Pre-post within-group evaluation; adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes |

N = 10 | Pre-post differences in diabetes- related stress and concerns about self-care in social situations were not significant, but there was a trend toward improvement in concerns about self-care in social situations. |

| Monaghan et al 2011(Monaghan et al., 2011) | Evaluate feasibility and initial efficacy of a telephone intervention based on social cognitive theory and incorporating cognitive-behavioral techniques for parents of young children with type 1 diabetes |

Randomized trial treatment vs. waitlist control group); Initial analyses were for prepost changes in the 14 parents assigned to the initial treatment group |

N = 14 | Parenting stress and perceived social support improved for parents after participating in the intervention. |

| Family Therapy | ||||

| Harris et al 2009(Harris et al., 2009) | Evaluate a 10-session, homebased Behavioral Family Systems Therapy (BFST) for adolescents with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes |

Pre-post evaluation with normative outcome comparison using data from adolescents with poor diabetes control included in a previous study |

N = 58 | The BFST intervention decreased diabetes-related family conflict by 1/3 to 1/2 of a standard deviation, and general family conflict decreased from 1/3 to 3/4 of a standard deviation. |

| Nansel et al 2009(Nansel et al., 2009) | Evaluate the feasibility of a family problem-solving behavioral intervention (WE*CAN) delivered by non-medical “Health Advisors” |

Randomized, controlled trial; families of children with type 1 diabetes were randomized to the family problem-solving intervention or usual care |

N = 122 | The intervention demonstrated good feasibility. No significant changes were observed in QOL, parent-child conflict, or family responsibility sharing, but study was not powered for outcome analysis. |

| Ellis et al(D. Ellis et al., 2008; D. A. Ellis, Naar-King, Templin, Frey, & Cunningham, 2007; D. A. Ellis, Templin, et al., 2007; D. A. Ellis, Yopp, et al., 2007) |

Evaluate Multisystemic Therapy MST) for adolescents with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes, and examine family composition (twoversus one-parent families) as a moderator of treatment effects |

Randomized, controlled trial; adolescents assigned to MST or control |

N = 127 | There was evidence for improved family relationships in two-parent families but not single-parent families. |

| Wysocki et al(Wysocki et al., 2007; Wysocki et al., 2006; Wysocki et al., 2008) |

Compare Behavioral Family Systems Therapy (BFST) intervention to an Educational Support (ES) group in families of adolescents with diabetes |

Randomized, controlled trial; families assigned to BFST, ES, or usual care |

N = 104 | At treatment end, those receiving BFST had improved family conflict and adherence compared to those receiving ES or usual care, with greater effects in adolescents with very poor initial metabolic control. BFST also resulted in greater improvements in family interaction and problem-solving relative to both ES and usual care. |

| Medications | ||||

| Echeverry et al 2009(Echeverry et al., 2009) | Compare sertraline versus placebo for treatment of depression in low-income Hispanic and African American patients with diabetes |

6-month randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial |

N = 87 | Depressive symptoms, QOL, and pain all improved in both the sertraline and placebo groups, with no significant differences between groups. |

| Williams et al 2007(Williams et al., 2007) | Examine effect of sertraline maintenance therapy on time-torecurrence of major depressive disorder in younger versus older adults with diabetes |

52-week follow-up of patients achieving depression recovery after participating in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial |

N = 152 | In younger patients, sertraline yielded significantly greater protection against depression recurrence than placebo, but there was no difference in recurrence for older patients treated with sertraline versus placebo. |

| Other Interventions | ||||

| Beever et al 2010(Beever, 2010) | Evaluate effect of 3-times weekly, 20-minute far-infrared sauna treatments on QOL in adults with type 2 diabetes |

Pre-post within-group comparison |

Physical health, general health, social functioning, stress, and fatigue improved from preintervention to post-intervention. |

|

| Skoro-Kondza et al 2009(Skoro-Kondza et al., 2009) | Evaluate community-based yoga classes for adults with type 2 diabetes |

Randomized trial; adults with type 2 diabetes (not on insulin) were randomized to participate in twice-weekly, 90- minute yoga classes for 12 weeks or waitlist control group |

N = 59 | The rate of ineligible patients was high, largely due to insulin treatment or contraindications to yoga (e.g., ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease), as was the rate of refusal due to lack of interest. The attendance rate at class was 50%. Intent-to-treat analyses showed no significant effects on QOL or self-efficacy. |

| Simson et al 2008(Simson et al., 2008) | Evaluate a supportive psychotherapy intervention with adult diabetes patients with lower extremity ulcers and co-morbid depression |

Randomized, controlled trial; adult inpatients with diabetes, lower extremity ulcers, and co-morbid depression were assigned to supportive psychotherapy or standard medical care |

N = 30 | Symptoms of anxiety and depression and diabetes-related distress decreased in the intervention group, but not the control group. |

| Menard et al 2007(Menard et al., 2007) | Evaluate effect of intensive multitherapy, consisting of monthly visits including individual and group DSME/T, intensive selfcare regimens for SMBG, diet, and exercise, 2 inter-visit phone calls for therapy adjustments, motivational support, and feedback, initiation/intensification of medication/insulin therapy if needed |

Randomized, controlled trial; French adult patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes and co-morbid hypertension and dyslipidemia assigned to intervention or standard medical care |

N = 72 | QOL was improved in the intervention group relative to control, along with knowledge and self-management behavior. No significant changes in attitudes about diabetes. |

| Benhamou et al 2007(Benhamou et al., 2007) | Evaluate a Web-based telemedicine intervention using cellular phones and short message service (SMS; i.e. texting) compared to usual care in adults with type 1 diabetes |

Bicenter, open-label, randomized, two-period, crossover 12-month study; adults with type 1 diabetes on pump therapy assigned to intervention or waitlist control |

N = 30 | QOL improved significantly more in the intervention group, and 76% of patients felt that the quality of their medical care was higher during the intervention period. |

| Approaches in Primary Care | ||||

| Ell et al 2010(Ell, Aranda, et al., 2010) | Compare effectiveness of collaborative depression care versus usual primary care in older versus younger adults with chronic physical illnesses, including diabetes, cancer, and others |

Pooled, intent-to-treat analyses of three randomized controlled trials of collaborative depression care consisting of choice of first-line depression therapy (psychotherapy, medication or both) and a structured algorithm for stepped care |

N = 1,081 |

Both younger and older patients experienced a significant improvement in depressive symptoms and major depression rates at 6-month follow-up, with no difference in effectiveness by age group. |

| Katon et al 2008(Katon et al., 2008) | Evaluate the 5-year effects of the Pathways depression collaborative care intervention versus usual primary care on total health care costs |

Randomized controlled trial at 9 HMO primary care practices; adults with diabetes and depression assigned to nurse depression intervention consisting of education about depression, behavioral activation, and choice of starting with antidepressant medication or problemsolving therapy in primary care + stepped care as needed |

N = 329 | There was a trend for reduced 5- year mean total medical costs in intervention patients (along with improved depression outcomes). The greatest cost reductions were seen in patients with most severe physical co-morbidity. |

| Simon et al 2007(Simon et al., 2007) | Evaluate cost and costeffectiveness of the Pathways depression collaborative care intervention versus usual primary care |

Randomized controlled trial at 9 HMO primary care practices; adults with diabetes and depression assigned to nurse depression intervention consisting of education about depression, behavioral activation, and choice of starting with antidepressant medication or problemsolving therapy in primary care + stepped care as needed |

N = 329 | The Pathways intervention increased days free from depression and led to savings in outpatient health services costs. Both contribute to an estimated 952 saved per patient treated with the Pathways intervention. |

| Ell et al 2010(Ell, Katon, et al., 2010) | Evaluate effectiveness of a socioculturally adapted collaborative care intervention in 387 lowincome, predominantly Hispanic adults with diabetes and depression at two public safetynet clinics |

Randomized, controlled trial; low-income, primary Hispanic adults with diabetes and depression assigned to collaborative care (initial choice of problem-solving therapy or medication or both, plus stepped care as needed) or enhanced usual care (primary care plus educational pamphlets and community resource list) |

N = 387 | Participants receiving collaborative care experienced greater improvements in depressive symptoms, diabetes symptoms, anxiety, emotional, physical, and pain-related functioning, disability, and social stressors. |

| Knight et al 2008(D. E. Knight et al., 2008) | Evaluate feasibility of screening for depression and usefulness of this screening for identifying undiagnosed and undertreated depression using a student pharmacist at ta pharmacistmanaged diabetes care clinic for underserved, low-income, inner city adult diabetes patients |

Cross-sectional study; patients attending a diabetes care clinic were screened for depression by a student pharmacist who then abstracted additional information from their chart |

N = 45 | The student pharmacist’s screening suggested that 75% of patients with previously diagnosed depression were being inadequately treated, and 48% of patients with no prior depression diagnosis had significant depressive symptoms. |

| Goss et al 2010(Goss et al., 2010) | Evaluate a new, interdisciplinary model of rural pediatric diabetes care called RADICAL, which involved a co-located team of pediatrician, diabetes educator, and mental health nurse who regularly meets to discuss each patient’s care, provided proactive child and family emotional support, and actively attempts to match insulin regimens with the patient’s lifestyle |

Pre-post evaluation of children under 21 years old with type 1 diabetes |

N = 61 | The RADICAL model resulted in increased patient satisfaction and elimination of a previously documented rural-urban disparity in patient QOL. |

| Jones et al 2006 (Jones, Turvey, Torner, & Doebbeling, 2006) |

Compare receipt of adequate antidepressant dosing and duration of therapy in veterans with versus without diabetes |

Retrospective cohort study of patients of a Midwestern Veterans Affairs facility, including those with co-morbid diabetes |

N = 2,332 |

In depressed veterans, dosing of antidepressants was adequate but treatment duration often fell short. A diabetes diagnosis did not adversely affect antidepressant treatment quality. |

Results

Part 1: Impact of Diabetes Treatments on Quality of Life

A total of 45 original research studies and 14 review articles were identified that examined psychosocial and QOL outcomes of different diabetes treatment approaches. One of the most active areas of research suggests mostly, but not entirely,3 positive effects of continuous subcutaneous insulin injection (CSII; i.e., insulin pump therapy) relative to multiple daily injections (MDI) on treatment satisfaction, emotional health, and QOL in youth with T1DM diabetes,4-9 their parents,5, 10-12 and adults with T1DM.13, 14 Although only the Opipari-Arrigan study involving preschoolers with T1DM and their parents11 used a randomized controlled design, the remaining observational studies have the advantage of increased generalizability to real-world shared decision-making about treatments (i.e., for patients who elect to use the pump, coping and QOL tends to improve). Insulin pump use in T2DM has been studied much less frequently. One study15 showed improved QOL and treatment satisfaction in patients switching from injections to CSII, but no effect in patients previously taking oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) only; another study16 reported no overall QOL differences for CSII versus MDI. Other treatment advances such as inhaled insulin,17, 18 continuous glucose monitoring,19-21 continuous intraperitoneal insulin infusion,22 pancreatic-kidney23 and islet cell24 transplantation, and supplemental metformin therapy25 in T1DM, have demonstrated positive QOL impacts, but small numbers of studies and observational designs prohibit any firm conclusions.

Another active area has been how to intensify treatment in T2DM in a way that maximizes QOL when initial lifestyle changes and OHAs fail to adequately control blood glucose. As evidenced by studies listed in Table 126-33 – all of which consisted of randomized controlled trials – treatment intensification in patients with poor glycemic control (e.g., >9.0%) typically improves both QOL and treatment satisfaction. In addition, there appears to be evidence of greater benefits when insulin or newer injectable agents (glucagon-like peptide (GLP) agonists and analogues, amylin analogues) are added to the patient’s medication regimen, versus adding another OHA (e.g., adding sitagliptin or pioglitazone to metformin only). This research, along with studies documenting high prevalence of side effects associated with OHAs,34, 35 suggest that insulin, and particularly insulin analogues,36-38 or other injectable agents, may be preferred over complex OHA regimens in T2DM patients.

Part 2: Interventions to Promote Healthy Coping

Table 2 summarizes key original research studies published in the past five years that evaluate interventions in terms of their effects on QOL and/or other psychosocial outcomes.

Several studies were identified that found diabetes self-management education to improve QOL39-42 and other psychosocial and emotional outcomes, such as depressive symptoms43 and treatment satisfaction,42 although in some cases, beneficial healthy coping effects were short-lived44 or not observed.45, 46 It is notable that of the five interventions in this category demonstrating positive effects, four focused on self-managing insulin in conjunction with diet for insulin-dependent and primarily T1DM patients.39-42 The only intervention targeted at patients with T2DM showing positive effects focused on self-monitoring of blood glucose and patient motivation, but did not employ a randomized, controlled design.43 This pattern of results suggests that QOL and other psychosocial outcomes in T2DM may require more intensive or coping-focused efforts beyond DSME.

Several studies suggested promising effects of adult patients’ participation in diabetes support groups in diverse settings, including two well-designed, randomized, controlled trials.47, 48 In the first trial, improved QOL in four domains (physical health, psychological health, social participation, and environment) was observed among Thai patients participating in a 16-week self-help group.47 In the second trial, improved perceptions of social support and willingness to initiate insulin were observed among male veterans participating in a reciprocal peer support program with supplemental group sessions, although diabetes-related distress was not significantly different across groups.48 Finally, a small pilot study demonstrated improved activity and vigor levels in urban, minority adults participating in peer-led community discussion circles, although did not elicit significant changes in other aspects of well-being.49 The diversity of the patient populations across these three studies suggest that the use of peer support may be a strategy that is potentially robust across patient subgroups, at least among adults. However, the few peer support studies identified overall, the lack of studies in youth with diabetes, and heterogeneity in the specific psychosocial outcomes assessed highlight the need for more research to understand the full potential of peer support in facilitating healthy coping.

Recent studies also provide evidence for the efficacy of problem-solving and coping skills interventions when delivered to adults with T2DM. A four-week problem-solving and cognitive reframing telephone-based intervention for older African American women was found to improve psychosocial adjustment and problem-solving, reduce uncertainty, and increase participation in physical activity in one randomized controlled trial.50, 51 Another intervention found that increasing one’s use of acceptance and mindfulness coping strategies improved diabetes self-care.52 These studies suggest that an emphasis on problem-solving may benefit psychosocial outcomes in addition to self-care behavior and glycemic control, although more studies evaluating a common set of healthy coping outcomes are again needed in this area as well.

There has been substantial interest in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), including several studies suggesting effectiveness of CBT-based interventions on depressive symptoms and diabetes-related stress, when delivered via novel formats, such as the internet and/or telephone.53-55 However, evidence from recent trials is mixed, with some suggestion of less favorable results when delivered to youth and/or youth-parent dyads54, 56 compared to parents alone55 or adult patients.53, 57-59 In addition, one recent randomized trial of group CBT suggests that CBT may be most helpful for patients who are experiencing higher versus lower levels of depressive symptoms.57 A recent review of interventions for individuals with diabetes and depression also noted the greatest improvements in depression for CBT compared to other psychotherapeutic or pharmacological approaches.60

Several studies of family therapy approaches applied to youth with T1DM and their families have produced good evidence of positive initial impacts on family conflict61, 62 and interaction,63 adherence,62 and problem-solving63. The methodological quality of these studies was high, with three of these four studies utilizing randomized, controlled designs comparing family therapy to usual care and/or education support. No family therapy interventions were identified for adults with either T1DM or T2DM, a major oversight in the literature.

Additional evidence for the efficacy of sertraline in reducing depressive symptoms among adult patients, as well as improving QOL and pain, was found in one randomized, double-blind, controlled trial with low-income minority patients with diabetes and co-morbid depression.64 However, another trial65 of the ability of sertraline to prevent recurrence of major depressive disorder in diabetes patients achieving initial depression recovery found evidence of efficacy only in younger patients, suggesting that non-medication approaches with older adults may be more appropriate. A notable gap in the literature is the absence of studies examining the use of antidepressant medication in conjunction with or in comparison to other non-pharmaceutical, guideline-recommended66 depression therapies (e.g., CBT, problem-solving therapy).

Other promising intervention approaches identified in the past five years via relatively small pilot studies include supportive psychotherapy for adults with co-morbid depression;67 intensive multi-therapy for improving QOL and self-care behavior;68 telemedicine support using short-messaging service (i.e., texting) for improving QOL;69 and far-infrared sauna treatments for improving physical health, general health, social functioning, stress, and fatigue.70 Larger, randomized trials of these approaches are warranted. There has also been interest in the utility of yoga classes for improving QOL, but one randomized trial found difficulties in implementing such classes and no impact on QOL.71

There has been considerable interest in developing and evaluating approaches to support healthy coping in the delivery of primary care; for example, collaborative care interventions for co-morbid depression in diabetes patients. Recent findings support the long-term maintenance of effects of collaborative care on depression,72, 73 and its effectiveness when applied to both younger and older patients,74 as well as in public safety-net clinics serving primarily low-income, Hispanic adults with diabetes.75 Other research supports the utility of the RADICAL model for eliminating rural-urban disparities in QOL among pediatric diabetes patients, which implements a co-located team consisting of a pediatrician, diabetes educator, and mental health nurse who meets regularly to discuss each patients’ care and provide preference-matched therapy and emotional support to children and their families.76 Additional research has demonstrated the feasibility of employing pharmacy students in a pharmacist-managed diabetes clinic to improve the identification of co-morbid depression in diabetes patients.77 Thus, innovative care models which integrate mental health care into traditional diabetes care settings appear to be a feasible and effective way of supporting healthy coping across different patient populations.

Discussion, Conclusions, and Implications

Findings from studies published in the past five years, and particularly the recent proliferation of articles examining psychosocial impacts of different diabetes treatments, suggest growing appreciation within the medical and research communities of the complex relationships between diabetes treatment, psychosocial factors, and metabolic control, and the importance of explicitly considering quality of life impacts when treating diabetes patients. The findings are also encouraging in that they suggest that there is much that diabetes educators and other health care providers can do to improve coping, emotional health, and QOL in their patients:

Treatment intensification in response to poor metabolic control often improves both clinical and quality-of-life outcomes.

Type of diabetes treatment may have a large impact on QOL and other psychosocial outcomes, suggesting that regimen changes in light of high levels of distress and/or low health-related QOL should be considered and discussed with patients. A wide range of instruments are available for assessing psychosocial and QOL impacts of diabetes and its treatment, as described previously.1.

Use of CSII in T1DM and other intensive therapies in diabetes generally, as well as earlier initiation of insulin and/or minimizing complexity of OHA regimens in T2DM diabetes specifically, can elicit improved emotional health and QOL.

A variety of intervention approaches for enhancing healthy coping continue to show positive results, providing educators and program planners an opportunity to choose and implement options based on the needs and preferences of their patients and available resources.

With regard to the treatment of co-morbid depression, CBT and collaborative care interventions have elicited some of the strongest supportive evidence for effectiveness in real-world settings.

From these conclusions, a broad pattern emerges of considerable importance. It seems now well established that, for a range of tactics and approaches to enhancing quality of diabetes care, better control of diabetes leads to better quality of life. Given the normality of multiple comorbidities in diabetes, clinicians may be hesitant to complicate regimens in a manner that adds too great a burden on patients. Also, it has long been recognized that adherence is compromised by complexity of treatment regimens.78 Nevertheless, it appears that enhancing the intensity of treatment when glycemic control is poor is typically associated not so much with greater experienced burden and distress but with feeling better.

Research Gaps

As the number and heterogeneity of medical treatments for controlling blood glucose in diabetes continues to expand, there remains an ongoing need for research comparing the effect of these different options on healthy coping outcomes. This research should examine the possibility that psychosocial and quality of life impacts of different treatments may vary across sub-populations, reflecting the different needs and unique circumstance of these groups. For example, the impacts of treatment intensification on quality of life among older, frail adults with multiple comorbidities may be very different than among those in their 40s or 50s whose principal medical problem is diabetes. Thus, there is a need for additional research comparing the effect of different diabetes treatment regimens on healthy coping outcomes in the growing population of older, frail diabetes patients with multiple co-morbidities. This is of critical importance given that in older, frail patients, given that medication-related problems, adverse events, and risk of hypoglycemia are much more common and minimizing treatment burden for patients and caregivers is of greater concern compared to intense glycemic control.79-81

As noted above, a number of diverse intervention approaches to directly targeting coping outcomes in diabetes patients have at least preliminary evidence supporting their efficacy and/or effectiveness. The downside of these multiple options is that diabetes educators may be uncertain as to which options may produce the best outcomes in their patient populations. There is a need to conduct head-to-head comparisons of different approaches identified in this review for directly targeting coping outcomes in diabetes with varying amounts of evidence for efficacy and effectiveness. In addition, some approaches have very good evidence in specific sub-populations (e.g., family therapy for youth with T1DM) but have been virtually untested in other populations where they may be similar useful (e.g., older patients with reduced functional independence). Future research should examine the feasibility and effectiveness of adapting such approaches for use with a broader range of patient populations.

Finally, there is a continued need1 for greater dissemination of approaches identified as efficacious or effective in a particular setting. The greatest challenge remains how to practically translate interventions into routine care so that more patients can benefit. More research into large-scale dissemination methods as well as intervention toolkits and guides is sorely needed. Among existing resources is “Healthy Coping in Diabetes: A Guide for Program Development and Implementation82. It and other materials developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Diabetes Initiative (http://diabetesnpo.im.wustl.edu/), as well as professional and patient-education materials of the American Association of Diabetes Educators and American Diabetes Association, may be especially helpful for those in the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding: Support was provided by the Health Innovation Program and the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR), grant UL1TR000427 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, and the Peers for Progress of the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation (Dr. Fisher). Additional funding for this project was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from The Wisconsin Partnership Program and the Centennial Scholars Program. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States government, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Wisconsin, or the University of North Carolina.

References

- 1.Fisher EB, Thorpe CT, Devellis BM, Devellis RF. Healthy coping, negative emotions, and diabetes management: A systematic review and appraisal. Diabetes Educ. 2007 Nov-Dec;33(6):1080–1103. doi: 10.1177/0145721707309808. discussion 1104-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siminoff LA, Gordon NH, Silverman P, Budd T, Ravdin PM. A decision aid to assist in adjuvant therapy choices for breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006 Nov;15(11):1001–1013. doi: 10.1002/pon.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu YP, Graves MM, Roberts MC, Mitchell AC. Is insulin pump therapy better than injection for adolescents with diabetes? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010 Aug;89(2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortina S, Repaske DR, Hood KK. Sociodemographic and psychosocial factors associated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010 Aug;11(5):337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller-Godeffroy E, Treichel S, Wagner VM. Investigation of quality of life and family burden issues during insulin pump therapy in children with Type 1 diabetes mellitus--a large-scale multicentre pilot study. Diabet Med. 2009 May;26(5):493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juliusson PB, Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Sovik O. The impact of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion on health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Acta Paediatr. 2006 Nov;95(11):1481–1487. doi: 10.1080/08035250600774114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofer SE, Heidtmann B, Raile K, et al. Discontinuation of insulin pump treatment in children, adolescents, and young adults. A multicenter analysis based on the DPV database in Germany and Austria. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010 Mar;11(2):116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cogen FR, Henderson C, Hansen JA, Streisand R. Pediatric quality of life in transitioning to the insulin pump: does prior regimen make a difference? Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007 Nov;46(9):777–779. doi: 10.1177/0009922807303224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight S, Northam E, Donath S, et al. Improvements in cognition, mood and behaviour following commencement of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. Diabetologia. 2009 Feb;52(2):193–198. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson V. Experiences of parents of young people with diabetes using insulin pump therapy. Paediatr Nurs. 2008 Mar;20(2):14–18. doi: 10.7748/paed2008.03.20.2.14.c6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opipari-Arrigan L, Fredericks EM, Burkhart N, Dale L, Hodge M, Foster C. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion benefits quality of life in preschool-age children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007 Dec;8(6):377–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingerski LM, Laffel L, Drotar D, Repaske D, Hood KK. Correlates of glycemic control and quality of life outcomes in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010 Dec;11(8):563–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheidegger U, Allemann S, Scheidegger K, Diem P. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy: effects on quality of life. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007 Aug 25;137(33-34):476–482. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todres L, Keen S, Kerr D. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion in Type 1 diabetes: patient experiences of ‘living with a machine’. Diabet Med. 2010 Oct;27(10):1201–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin RR, Peyrot M, Chen X, Frias JP. Patient-reported outcomes from a 16-week open-label, multicenter study of insulin pump therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010 Nov;12(11):901–906. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurkova E, Cap J, Ziakova K. Quality of life and treatment satisfaction in the context of diabetes self-management education. Int J Nurs Pract. 2009 Apr;15(2):91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Satisfaction and quality of life with premeal inhaled versus injected insulin in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007 Jun;30(6):1399–1405. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee IT, Liu HC, Liau YJ, Lee WJ, Huang CN, Sheu WH. Improvement in health-related quality of life, independent of fasting glucose concentration, via insulin pen device in diabetic patients. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009 Aug;15(4):699–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cemeroglu AP, Stone R, Kleis L, Racine MS, Postellon DC, Wood MA. Use of a real-time continuous glucose monitoring system in children and young adults on insulin pump therapy: patients’ and caregivers’ perception of benefit. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010 May;11(3):182–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halford J, Harris C. Determining clinical and psychological benefits and barriers with continuous glucose monitoring therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010 Mar;12(3):201–205. doi: 10.1089/dia.2009.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fritschi C, Quinn L, Penckofer S, Surdyk PM. Continuous glucose monitoring: the experience of women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010 Mar-Apr;36(2):250–257. doi: 10.1177/0145721709355835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Logtenberg SJ, Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, Groenier KH, Gans RO, Bilo HJ. Health-related quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and costs associated with intraperitoneal versus subcutaneous insulin administration in type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jun;33(6):1169–1172. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isla Pera P, Moncho Vasallo J, Torras Rabasa A, Oppenheimer Salinas F, Fernandez Cruz Perez L, Ricart Brulles MJ. Quality of life in simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2009 Sep-Oct;23(5):600–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tharavanij T, Betancourt A, Messinger S, et al. Improved long-term health-related quality of life after islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2008 Nov 15;86(9):1161–1167. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818a7f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moon RJ, Bascombe LA, Holt RI. The addition of metformin in type 1 diabetes improves insulin sensitivity, diabetic control, body composition and patient well-being. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007 Jan;9(1):143–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Best JH, Rubin RR, Peyrot M, et al. Weight-related quality of life, health utility, psychological well-being, and satisfaction with exenatide once weekly compared with sitagliptin or pioglitazone after 26 weeks of treatment. Diabetes Care. 2011 Feb;34(2):314–319. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Polonsky WH. Diabetes distress and its association with clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with pramlintide as an adjunct to insulin therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2008 Dec;10(6):461–466. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Polonsky WH, Best JH. Patient reported outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes on basal insulin randomized to addition of mealtime pramlintide or rapid-acting insulin analogs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010 May;26(5):1047–1054. doi: 10.1185/03007991003634759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bode BW, Testa MA, Magwire M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment with the human GLP-1 analogue liraglutide or glimepiride in monotherapy: results from a randomized controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010 Jul;12(7):604–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ushakova O, Sokolovskaya V, Morozova A, et al. Comparison of biphasic insulin aspart 30 given three times daily or twice daily in combination with metformin versus oral antidiabetic drugs alone in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a 16-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial conducted in russia. Clin Ther. 2007 Nov;29(11):2374–2384. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lingvay I, Legendre JL, Kaloyanova PF, Zhang S, Adams-Huet B, Raskin P. Insulin-based versus triple oral therapy for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: which is better? Diabetes Care. 2009 Oct;32(10):1789–1795. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houlden R, Ross S, Harris S, Yale JF, Sauriol L, Gerstein HC. Treatment satisfaction and quality of life using an early insulinization strategy with insulin glargine compared to an adjusted oral therapy in the management of Type 2 diabetes: the Canadian INSIGHT Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007 Nov;78(2):254–258. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vinik AI, Zhang Q. Adding insulin glargine versus rosiglitazone: health-related quality-of-life impact in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007 Apr;30(4):795–800. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Florez H, Luo J, Castillo-Florez S, et al. Impact of metformin-induced gastrointestinal symptoms on quality of life and adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med. 2010 Mar;122(2):112–120. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.03.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollack MF, Purayidathil FW, Bolge SC, Williams SA. Patient-reported tolerability issues with oral antidiabetic agents: Associations with adherence; treatment satisfaction and health-related quality of life. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010 Feb;87(2):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masuda H, Sakamoto M, Irie J, et al. Comparison of twice-daily injections of biphasic insulin lispro and basal-bolus therapy: glycaemic control and quality-of-life of insulin-naive type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008 Dec;10(12):1261–1265. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishii H, Anderson JH, Jr., Yamamura A, Takeuchi M, Ikeda I. Improvement of glycemic control and quality-of-life by insulin lispro therapy: Assessing benefits by ITR-QOL questionnaires. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008 Aug;81(2):169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada S, Watanabe M, Kitaoka A, et al. Switching from premixed human insulin to premixed insulin lispro: a prospective study comparing the effects on glucose control and quality of life. Intern Med. 2007;46(18):1513–1517. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe J, Linjawi S, Mensch M, James K, Attia J. Flexible eating and flexible insulin dosing in patients with diabetes: Results of an intensive self-management course. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008 Jun;80(3):439–443. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bendik CF, Keller U, Moriconi N, et al. Training in flexible intensive insulin therapy improves quality of life, decreases the risk of hypoglycaemia and ameliorates poor metabolic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009 Mar;83(3):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Di Bartolo P, et al. Diabetes Interactive Diary: a new telemedicine system enabling flexible diet and insulin therapy while improving quality of life: an open-label, international, multicenter, randomized study. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jan;33(1):109–115. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speight J, Amiel SA, Bradley C, et al. Long-term biomedical and psychosocial outcomes following DAFNE (Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating) structured education to promote intensive insulin therapy in adults with sub-optimally controlled Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010 Jul;89(1):22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kempf K, Kruse J, Martin S. ROSSO-in-praxi: a self-monitoring of blood glucose-structured 12-week lifestyle intervention significantly improves glucometabolic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010 Jul;12(7):547–553. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bastiaens H, Sunaert P, Wens J, et al. Supporting diabetes self-management in primary care: pilot-study of a group-based programme focusing on diet and exercise. Prim Care Diabetes. 2009 May;3(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nansel TR, Iannotti RJ, Simons-Morton BG, et al. Diabetes personal trainer outcomes: short-term and 1-year outcomes of a diabetes personal trainer intervention among youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007 Oct;30(10):2471–2477. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang TS, Funnell MM, Brown MB, Kurlander JE. Self-management support in “real-world” settings: an empowerment-based intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010 May;79(2):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chaveepojnkamjorn W, Pichainarong N, Schelp FP, Mahaweerawat U. A randomized controlled trial to improve the quality of life of type 2 diabetic patients using a self-help group program. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009 Jan;40(1):169–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heisler M, Vijan S, Makki F, Piette JD. Diabetes control with reciprocal peer support versus nurse care management: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Oct 19;153(8):507–515. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Comellas M, Walker EA, Movsas S, Merkin S, Zonszein J, Strelnick H. Training community health promoters to implement diabetes self-management support programs for urban minority adults. Diabetes Educ. 2010 Jan-Feb;36(1):141–151. doi: 10.1177/0145721709354606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amoako E, Skelly AH. Managing uncertainty in diabetes: an intervention for older African American women. Ethn Dis. Summer. 2007;17(3):515–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amoako E, Skelly AH, Rossen EK. Outcomes of an intervention to reduce uncertainty among African American women with diabetes. West J Nurs Res. 2008 Dec;30(8):928–942. doi: 10.1177/0193945908320465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007 Apr;75(2):336–343. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Bastelaar KM, Pouwer F, Cuijpers P, Riper H, Snoek FJ. Web-based depression treatment for type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011 Feb;34(2):320–325. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salamon KS, Hains AA, Fleischman KM, Davies WH, Kichler J. Improving adherence in social situations for adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM): a pilot study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010 Apr;4(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monaghan M, Hilliard ME, Cogen FR, Streisand R. Supporting parents of very young children with type 1 diabetes: results from a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 Feb;82(2):271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lehmkuhl HD, Storch EA, Cammarata C, et al. Telehealth behavior therapy for the management of type 1 diabetes in adolescents. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010 Jan;4(1):199–208. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snoek FJ, van der Ven NC, Twisk JW, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) compared with blood glucose awareness training (BGAT) in poorly controlled Type 1 diabetic patients: long-term effects on HbA moderated by depression. A randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2008 Nov;25(11):1337–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Bastelaar KM, Pouwer F, Cuijpers P, Twisk JW, Snoek FJ. Web-based cognitive behavioural therapy (W-CBT) for diabetes patients with co-morbid depression: design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amsberg S, Anderbro T, Wredling R, et al. A cognitive behavior therapy-based intervention among poorly controlled adult type 1 diabetes patients--a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2009 Oct;77(1):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Nuyen J, Stoop C, et al. Effect of interventions for major depressive disorder and significant depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010 Jul-Aug;32(4):380–395. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harris MA, Freeman KA, Beers M. Family therapy for adolescents with poorly controlled diabetes: initial test of clinical significance. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 Nov-Dec;34(10):1097–1107. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wysocki T, Harris MA, Buckloh LM, et al. Effects of behavioral family systems therapy for diabetes on adolescents’ family relationships, treatment adherence, and metabolic control. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006 Oct;31(9):928–938. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wysocki T, Harris MA, Buckloh LM, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of Behavioral Family Systems Therapy for Diabetes: maintenance and generalization of effects on parent-adolescent communication. Behav Ther. 2008 Mar;39(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Echeverry D, Duran P, Bonds C, Lee M, Davidson MB. Effect of pharmacological treatment of depression on A1C and quality of life in low-income Hispanics and African Americans with diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009 Dec;32(12):2156–2160. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Williams MM, Clouse RE, Nix BD, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in prevention of depression recurrence in older versus younger adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007 Apr;30(4):801–806. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi BCK, Pak AWP. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 2. Promotors, barriers, and strategies of enhancement. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(6):E224–E232. doi: 10.25011/cim.v30i6.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simson U, Nawarotzky U, Friese G, et al. Psychotherapy intervention to reduce depressive symptoms in patients with diabetic foot syndrome. Diabet Med. 2008 Feb;25(2):206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Menard J, Payette H, Dubuc N, Baillargeon JP, Maheux P, Ardilouze JL. Quality of life in type 2 diabetes patients under intensive multitherapy. Diabetes Metab. 2007 Feb;33(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Benhamou PY, Melki V, Boizel R, et al. One-year efficacy and safety of Web-based follow-up using cellular phone in type 1 diabetic patients under insulin pump therapy: the PumpNet study. Diabetes Metab. 2007 Jun;33(3):220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beever R. The effects of repeated thermal therapy on quality of life in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. J Altern Complement Med. 2010 Jun;16(6):677–681. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Skoro-Kondza L, Tai SS, Gadelrab R, Drincevic D, Greenhalgh T. Community based yoga classes for type 2 diabetes: an exploratory randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski PS. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008 Jun;31(6):1155–1159. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;64(1):65–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ell K, Aranda MP, Xie B, Lee PJ, Chou CP. Collaborative depression treatment in older and younger adults with physical illness: pooled comparative analysis of three randomized clinical trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;18(6):520–530. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010 Apr;33(4):706–713. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goss PW, Paterson MA, Renalson J. A ‘radical’ new rural model for pediatric diabetes care. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010 Aug;11(5):296–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knight DE, Draeger RW, Heaton PC, Patel NC. Pharmacist screening for depression among patients with diabetes in an urban primary care setting. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008 Jul-Aug;48(4):518–521. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.World Health Organization . Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 79.California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatrics Society Panel on Improving Care for Elders with Diabetes Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 May;51(5):S265–S280. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.51.5s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care. 2011 Jan;34(Suppl 1):S11–61. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Feil DG, Rajan M, Soroka O, Tseng CL, Miller DR, Pogach LM. Risk of hypoglycemia in older veterans with dementia and cognitive impairment: implications for practice and policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011 Dec;59(12):2263–2272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fisher EB, Thorpe C, Brownson CA, et al. Healthy Coping in Diabetes: A Guide for Program Development and Implementation. Diabetes Initiative National Program Office (NPO); Princeton, NJ: Aug, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 83.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:386–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995 Jun;18(6):754–760. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005 Mar;28(3):626–631. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Welch G, Dunn SM, Beeney LJ. The ATT39: A measure of psychological adjustment to diabetes. In: Bradley C, editor. Handbook of Psychology and Diabetes. Harwood Academic Publishers; Chur, Switzerland: 1994. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Campbell WH, Anderson WK, Burckart GJ, et al. Institutional and faculty roles and responsibilities in the emerging environment of university-wide interdisciplinary research structures: Report of the 2001-2002 Research and Graduate Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002 Win66:28s–33s. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Utz SW, Williams IC, Jones R, et al. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008 Sep-Oct;34(5):854–865. doi: 10.1177/0145721708323642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ismail K, Maissi E, Thomas S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy and motivational interviewing for people with Type 1 diabetes mellitus with persistent sub-optimal glycaemic control: a Diabetes and Psychological Therapies (ADaPT) study. Health Technol Assess. 2010 May;14(22):1–101. iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta14220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nansel TR, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM, et al. A multisite trial of a clinic-integrated intervention for promoting family management of pediatric type 1 diabetes: feasibility and design. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009 Apr;10(2):105–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ellis DA, Yopp J, Templin T, et al. Family mediators and moderators of treatment outcomes among youths with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007 Mar;32(2):194–205. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ellis D, Naar-King S, Templin T, et al. Multisystemic therapy for adolescents with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes: reduced diabetic ketoacidosis admissions and related costs over 24 months. Diabetes Care. 2008 Sep;31(9):1746–1747. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]