Abstract

The ammonia-oxidizing archaea have recently been recognized as a significant component of many microbial communities in the biosphere. Although the overall stoichiometry of archaeal chemoautotrophic growth via ammonia (NH3) oxidation to nitrite (NO2−) is superficially similar to the ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, genome sequence analyses point to a completely unique biochemistry. The only genomic signature linking the bacterial and archaeal biochemistries of NH3 oxidation is a highly divergent homolog of the ammonia monooxygenase (AMO). Although the presumptive product of the putative AMO is hydroxylamine (NH2OH), the absence of genes encoding a recognizable ammonia-oxidizing bacteria-like hydroxylamine oxidoreductase complex necessitates either a novel enzyme for the oxidation of NH2OH or an initial oxidation product other than NH2OH. We now show through combined physiological and stable isotope tracer analyses that NH2OH is both produced and consumed during the oxidation of NH3 to NO2− by Nitrosopumilus maritimus, that consumption is coupled to energy conversion, and that NH2OH is the most probable product of the archaeal AMO homolog. Thus, despite their deep phylogenetic divergence, initial oxidation of NH3 by bacteria and archaea appears mechanistically similar. They however diverge biochemically at the point of oxidation of NH2OH, the archaea possibly catalyzing NH2OH oxidation using a novel enzyme complex.

Microbial oxidation of ammonia (NH3) to nitrite (NO2−), the first step in nitrification, plays a central role in the global cycling of nitrogen. Recent studies have established that marine and terrestrial representatives of an abundant group of archaea, now classified as Thaumarchaeota, are autotrophic NH3 oxidizers (1–5). Despite increasing evidence that ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) generally outnumber ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB), and likely nitrify in most natural environments, very little is known about their physiology or supporting biochemistry (6, 7). Genome sequence analyses have pointed to a unique pathway for NH3 oxidation, likely using copper as a major redox active metal, and coupled to a variant of the hydroxypropionate/hydroxybutyrate cycle (8). However, the only genome sequence feature that associates the archaeal pathway for NH3 oxidation with that of the better characterized AOB is a divergent variant of the ammonia monooxygenase (AMO), which may or may not be a functional equivalent of the bacterial AMO. Thus, the supporting biochemistry of a biogeochemically significant group of microorganisms remains unresolved (8, 9).

Among the AOB, as represented by the model organism Nitrosomonas europaea, NH3 is first oxidized to hydroxylamine (NH2OH) by AMO, an enzyme composed of three subunits encoded by amoC, amoA, and amoB genes (7). NH2OH is subsequently oxidized to NO2− by the hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) (7), a heme-rich enzyme encoded by the hao gene (7). Of the four electrons released from the oxidation of NH2OH to NO2−, two are transferred to the terminal oxidase for respiratory purposes and two are transferred to AMO for further oxidation of NH3 (7). Although all available genome sequences for the AOA contain homologs of the bacterial AMO (amoB, amoC, and amoA), there are no obvious homologs of AOB-like HAO, or cytochromes c554 and cM552 critical for energy conversion in AOB (8–15). Thus, either the product of NH3 oxidation is not NH2OH or, alternatively, these phylogenetically deeply branching thaumarchaea use a novel biochemistry for NH2OH oxidation and electron transfer (8).

In an attempt to gain further insights into the biochemistry and physiology of these unique archaeal nitrifiers, we here investigated the role of NH2OH in Nitrosopumilus maritimus metabolism. These studies were complicated by the extremely oligotrophic character of this organism contributing to very low cell densities in culture (16). To overcome the challenge of working with low cell density cultures of N. maritimus, we established a method to concentrate cells on nylon membrane filters such that the cells remained competent for NH3-dependent NO2− formation and oxygen (O2) uptake. This method enabled us to carry out relatively short duration physiological studies and stable isotope tracer experiments directed at determining if N. maritimus can oxidize exogenous NH2OH to NO2− while consuming O2 and producing ATP, and if NH2OH is an intermediate in NH3 oxidation pathway of N. maritimus.

Results

N. maritimus Oxidizes NH2OH to NO2−.

The apparent lack of genes encoding a recognizable AOB-like HAO complex in the genome of N. maritimus has generated considerable interest in the pathway of NH3 oxidation in AOA (8). Because purification and direct biochemical characterization of AMO enzymes has thus far been unsuccessful, we aimed to determine if N. maritimus could convert NH2OH to NO2−. To determine if N. maritimus can oxidize NH2OH to NO2−, it was necessary to expose the N. maritimus cells to NH2OH in the absence of the NH4+ used to grow the culture. Hence, a technique was developed to concentrate the cells onto 0.2-µm pore size nylon membrane filters using a vacuum manifold system. The manifold system allowed simultaneous filtration of several liters of culture. In addition to concentrating the cells and separating them from residual NH4+ in the medium, the nylon membranes served as a solid support for convenient handling of concentrated cells in subsequent incubation assays. The membrane-associated N. maritimus cells actively oxidized NH3 for several hours.

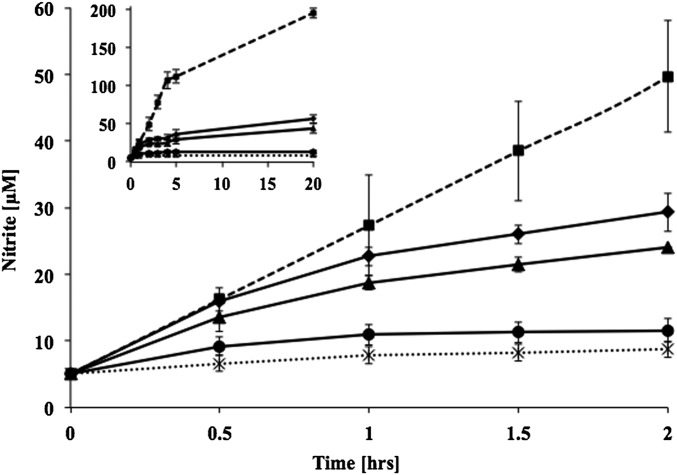

To investigate whether NH2OH can be oxidized by N. maritimus, a series of short-term NO2− accumulation assays was conducted, in which membrane-associated N. maritimus cells were exposed to various concentrations of NH2OH. Irrespective of the initial concentration of NH2OH (50–200 µM), N. maritimus oxidized ∼50 µM NH2OH to NO2− over 20 h (Fig. 1). During the first 30 min of exposure to 200 µM NH2OH, the rate of NH2OH-dependent NO2− production was equal to the rate of NH3-dependent NO2− production [0.19 ± 0.01 µmol/(min × mg protein)]. With longer incubation times, the rate of NH2OH oxidation decreased gradually and finally stopped after accumulation of ∼50 µM of NO2− (Fig. 1). Addition of 1 mM NH2OH led to a complete inhibition of the NO2− formation (Fig. 1), reflecting a toxicity at higher concentrations also observed for AOB (17). Attempts to grow N. maritimus on NH2OH as sole energy source failed as previously observed in N. europaea (18).

Fig. 1.

Accumulation of NO2− by N. maritimus. Determinations in the presence of 200 µM NH4+ (dashed lines, squares), 200 µM NH2OH (solid lines, diamonds), 50 µM NH2OH (solid lines, triangles), 1 mM NH2OH (solid lines, circles), and no substrate (dashed lines, crosses). Inset shows accumulation of NO2− after 20 h of incubation. Data are means of triplicates, with variation less than 10%. The experiment was repeated at least three times and produced similar results. Error bars represent SEM.

Acetylene (C2H2) (19) and allylthiourea (ATU) (20) are specific inhibitors of NH3 oxidation by AMO in AOB and AOA (19–21). In the present work, the ability of N. maritimus to oxidize NH3 or NH2OH in presence of either C2H2 or ATU was analyzed by monitoring NO2− accumulation. C2H2 (0.1%) was added to the headspace of sealed bottles containing membrane-attached N. maritimus cells in synthetic crenarchaeota medium (SCM) containing either NH4+ or NH2OH. C2H2 completely inhibited NH3-dependent NO2− accumulation but had no effect on NH2OH-dependent NO2− production (Fig. S1 A and B) as previously observed in N. europaea (19). Similarly, the addition of ATU also inhibited NH3-dependent NO2− production but did not inhibit NH2OH-dependent NO2− production (Fig. S1 A and B) (20). These results clearly indicate that N. maritimus can oxidize NH2OH and its oxidation is independent of the AMO activity (Fig. S1 A and B).

NH2OH Oxidation Is Coupled to O2 Uptake in N. maritimus.

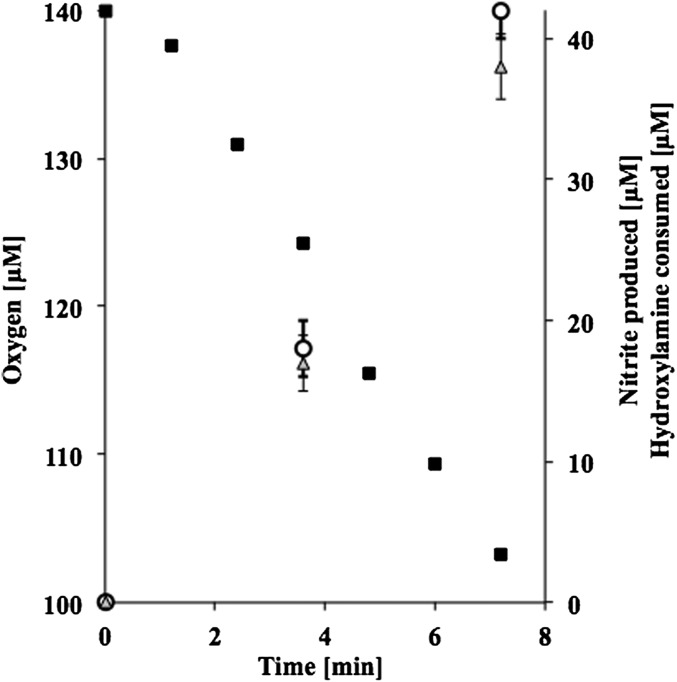

Further experiments were conducted to determine if oxidation of NH2OH to NO2− by N. maritimus is accompanied by consumption of a stoichiometric amount of O2. To test this, NH2OH consumption, O2 uptake, and NO2− accumulation were independently determined (Fig. 2). The rate of NH2OH-dependent O2 consumption by N. maritimus remained constant for 8 min at a rate of 0.20 ± 0.01 µmol O2/(min × mg protein) and the ratio of O2 consumed to NO2− produced was 1 ± 0.04 (Fig. 2). This stoichiometry is similar to that observed in AOB (22). By comparison, the rate of O2 consumption in the presence of NH4+ (200 µM) was 0.28 ± 0.03 µmol O2/(min × mg protein) and reflects the stoichiometry of 1 NH3:1.5 O2 previously reported for both the bacterial and archaeal oxidation of NH3 to NO2− (16, 23). Substrate depleted N. maritimus cells consumed only 0.003 ± 0.001 µmol O2 per minute per milligram protein. This endogenous rate of O2 uptake by N. maritimus was 50–100 times lower compared with the O2 uptake rate observed with NH3 or NH2OH and consequently provides a good measure of the O2 uptake rates observed during NH3 or NH2OH oxidation.

Fig. 2.

Stoichiometry of NH2OH oxidation in N. maritimus. O2 uptake (solid squares), NH2OH consumed (open circles), NO2− produced (gray triangles); Data are means of triplicates, with variation of less than 10%. Incubations were carried out for 8 min while the conditions were at optimum (i.e., the unavoidable degradation of NH2OH did not interfere with the stoichiometry). The experiment was repeated at least three times and produced similar results. Error bars represent SEM.

To evaluate the possibility that NO2− was produced from NH2OH before inhibition by C2H2 or ATU was maximal, NH3-dependent and NH2OH-dependent O2 consumption were studied in the presence of either C2H2 or ATU. Membrane-immobilized N. maritimus cells were treated with C2H2 for 2 h before placing them in the O2 electrode chamber. C2H2-exposed cells commenced respiring immediately after the addition of NH2OH (Fig. S2A). Similarly, ATU-inhibited N. maritimus cells immediately resumed O2 consumption upon addition of NH2OH (Fig. S2B). In agreement with previous observations (2), higher concentrations of ATU (2.5 mM) were required in our studies as well to completely stop NH3-dependent NO2− accumulation and O2 uptake in N. maritimus, whereas as little as 10 µM ATU concentrations inhibited NH3-dependent NO2− accumulation and O2 uptake in N. europaea (20). The fact that C2H2 or ATU did not inhibit NH2OH-dependent O2 uptake clearly indicates that NH2OH oxidation is not dependent on AMO (Fig. S2 A and B).

NH2OH Oxidation Is Coupled to ATP Production in N. maritimus.

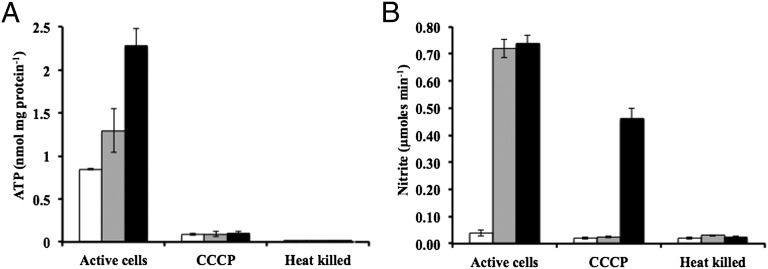

If NH2OH is an intermediate of NH3 oxidation in N. maritimus analogous to the AOB, then the oxidation of NH2OH should be coupled to the respiratory electron transfer chain and ultimately to the reduction of O2, and to ATP synthesis. Indeed, we demonstrated that NH2OH oxidation is coupled stoichiometrically (1:1) to reduction of O2 (see above), suggesting electron transfer from NH2OH to O2. Given the limited N. maritimus biomass available, direct measurement of electron transport or proton translocation in response to NH2OH was impossible. Thus, to confirm the metabolic coupling of NH2OH oxidation, we measured ATP levels and NO2− production rates in the presence of different substrates. Cellular ATP levels were measured following addition of SCM media containing either no substrate, NH4+, or NH2OH to membrane-immobilized N. maritimus cells. Cells incubated in the presence of NH2OH showed statistically significantly higher levels of ATP compared with cells incubated without substrate (P value 0.006). Furthermore, cells incubated with NH2OH showed statistically significantly higher ATP levels compared with cells incubated with NH4+ (P value 0.007) (Fig. 3A) although the NO2− produced in presence of either NH4+ or NH2OH is almost similar (Fig. 3B). Addition of either carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP), a well-characterized uncoupler of ATP synthesis, or use of heat-killed cells, prevented NH3-dependent or NH2OH-dependent increase in ATP levels in all treatments (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, CCCP addition diminished NO2− production from NH3, but not NO2− production from incubation with NH2OH (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that the respiratory reduction of O2 associated with NH2OH oxidation is coupled to ATP production in N. maritimus, as has been reported in N. europaea (24). Inhibition of NO2− production from NH3 by CCCP further suggests that analogous to the AOB, the oxidation of NH3 in N. maritimus by AMO also depends on input of electrons from electron carriers (7). Consistent with this dual sink of electrons in the NH3 oxidation metabolism, the cellular level of ATP is lower during incubation with NH4+ compared with incubations with NH2OH only (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

ATP formation by N. maritimus. (A) ATP and (B) NO2− concentration in N. maritimus cells incubated in presence of either no substrate (white bars), 200 µM NH4+ (gray bars), or 200 µM NH2OH (black bars). Concentration of ATP and NO2− in heat-killed cells and cells treated with 100 µM CCCP for 20 min is also shown. The NO2− trace amounts detected in the controls are likely due to leaching of residual traces of NO2− in the nylon filters used to harvest N. maritimus cells. Error bars represent the SEM.

Generation of NH2OH from NH3.

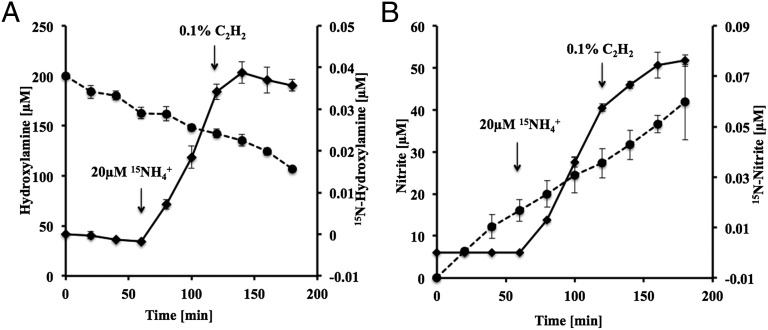

We used stable isotope tracer experiments to further establish that NH2OH is an intermediate in the NH3 oxidation pathway of N. maritimus. Membrane-immobilized cells were incubated with natural abundance NH4Cl and NH2OH (200 µM each). The 15N isotopic composition of NH2OH and accumulated NO2− were measured over time by isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IR-MS) following chemical conversion of NH2OH or NO2− to nitrous oxide (N2O) by iron acetate (FeAc) or sodium azide, respectively (25). NH2OH-derived N2O and N2O present in the control vials before chemical conversion of NH2OH to N2O were quantified by gas chromatography (GC). During 60 min of incubation, NO2− concentrations steadily increased and NH2OH concentrations decreased (Fig. 4 A and B). After addition of 20 µM 15NH4Cl, the relative abundance of 15N increased over time in the NH2OH and NO2− pools (Fig. 4 A and B). After 120 min, NH3 oxidizing activity was blocked by addition of C2H2. Accumulation of 15N stopped completely in the NH2OH pool within 20 min of C2H2 addition, indicating complete inhibition of metabolism of highly 15N-labeled NH3. In contrast, uptake and oxidation of then significantly 15N-enriched NH2OH pool continued, leading to further accumulation of 15NO2− at a lower rate (Fig. 4 A and B). Due to rapid decomposition of NH2OH in SCM media, we could not establish the mass and isotope balance among NH4+, NH2OH, and NO2− in our 15N experiments. Moreover, presence of high concentrations of NH2OH was toxic to N. maritimus and slowed down the rates of NH4+ oxidation and NO2−production.

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of N. maritimus NH2OH consumption and accumulation of 15N in a stable isotope tracer experiment. N. maritimus cells were incubated in the presence of 200 µM NH4Cl and 200 µM NH2OH. After 60 min (arrow) 20 µM 15NH4Cl (99.5% purity) was added to the cell suspension. After 120 min NH3-oxidation activity was blocked by addition of C2H2 (0.1%). (A) Consumption of NH2OH (dashed lines, filled circles) and accumulation of 15N in NH2OH pool (solid lines, filled diamonds). (B) Accumulation of NO2− (dashed lines, filled circles), 15N in NO2− pools (solid lines, filled diamonds).

Because the determination of δ15N signatures of NH2OH and NO2− entailed a chemical conversion step affording the more stable N2O for subsequent stable isotope analysis, a series of controls were conducted to exclude other sources of 15N accumulation in the N2O pool. Neither NH4+ itself, nor N2H4 were found to yield N2O by the chemical conversion method used here, thus, ruling out a possible interference by NH4+ itself or a role of N2H4 in the N. maritimus metabolism. We further eliminated the possibility of generation of N2O in N. maritimus cell suspensions from chemical decomposition of unstable N species, such as nitric oxide (NO), nitroxyl (HNO), or nitrosyl (NO+), or their rapid reaction with added NH2OH. Although such chemical reactions cannot be completely excluded, their significance during our experiments must be negligible because N2O concentrations in the control vials did not increase over time, indicating no significant new production of N2O through either of these reactions. Thus, although NH2OH does not accumulate at measurable concentrations during normal growth of N. maritimus in culture, production and consumption of NH2OH during oxidation of NH3 remains the only plausible explanation for our observed results, indicating that NH2OH is an intermediate in the NH3 oxidation pathway of N. maritimus.

Discussion

The lack of an identifiable gene encoding HAO in the genome of N. maritimus (8) necessitates either a novel enzyme for the oxidation of NH2OH or, alternatively, an initial product of NH3 oxidation other than NH2OH (8). We earlier speculated that the immediate oxidation product of the archaeal variant of AMO might be a reactive N species, such as nitroxyl, instead of NH2OH (8). However, the data presented in this study now clearly implicate NH2OH as the immediate product of AMO, with properties similar to those previously observed in N. europaea (20). NO2− accumulation and O2 uptake during NH2OH oxidation by N. maritimus were stoichiometrically coupled (Fig. 2) and closely paralleled NH2OH disappearance and therefore fulfilled the expected 1:1 stoichiometry of NH2OH and O2 consumption. Metabolism of NH2OH was not inhibited by C2H2 or ATU, two well-characterized inhibitors of the bacterial AMO. Both archaeal and bacterial NH3 oxidation are inhibited by C2H2, a mechanism-based inactivator of NH3 oxidation in the AOB (Fig. S1A) (21, 26). As observed in AOB, C2H2 did not inactivate NH2OH oxidation in N. maritimus (Fig. S1A). Previously, C2H2 was shown to be a suicidal substrate for AMO in N. europaea and that protein synthesis was essential for recovery from C2H2 inactivation (19, 26). N. maritimus cells inactivated by C2H2 also require a recovery period, not showing any respiratory capacity until 60–90 min following NH4+ addition. In addition, the oxidation of NH2OH by N. maritimus remained virtually unaffected by concentrations of ATU, an inhibitor of the bacterial AMO, that completely inhibits AOB and AOA NH3 oxidation at the concentrations used in our experiments (Fig. S1B) (20). Thus, although the enzymes and metabolic pathway of AOA have not yet been characterized (8–12), we have now shown that N. maritimus is capable of oxidizing NH2OH in presence of C2H2 similar to N. europaea. Thus, we can also discard the possibility that C2H2 interferes with components other than the AMO protein in the AOA.

Having demonstrated that NH2OH can be oxidized to NO2− by N. maritimus, we then considered whether this oxidation provided a benefit to the cells. This is a necessary consequence of NH2OH serving as an intermediate in NH3 oxidation, because all electrons for respiration are derived from the oxidation of NH2OH. Indeed, a benefit was observed by marked ATP production in response to NH2OH addition relative to resting cells without substrate (Fig. 3A). Similar, but lower, ATP production coupled to oxidation of NH2OH was measured in N. europaea (24, 27). Although we have no explanation for this differential response, N. maritimus may maintain a slightly higher energy charge than that characterized for AOB.

Direct evidence that the oxidation of NH3 to NO2− by N. maritimus proceeds via NH2OH came from stable isotope tracer experiments in which 15NH2OH production was detected while N. maritimus was oxidizing 15NH3 (Fig. 4A). One possible caveat to this interpretation is that accumulation of 15NH2OH was measured by IR-MS after its conversion to 15N2O. Recent reports demonstrated that archaeal NH3 oxidation produces N2O (28) albeit no biochemical pathway for its production in AOA has been identified (29). Production of N2O either by N. maritimus itself or chemical reactions affording N2O in our growth media, e.g., through decomposition of NH2OH, could potentially yield N2O that would interfere with NH2OH isotopic analysis. We attempted to quantify N2O concentrations and isotopic composition in parallel in iron acetate-converted and -unconverted samples under identical conditions. However, N2O concentrations in the unconverted samples were too low and outside the calibration range of our IR-MS setup, even after increasing the injection volume 10-fold. We estimate the highest N2O concentration in any unconverted sample was 6–10 nM (median 7.75, SD 1.6, n = 9) and it neither increased nor decreased significantly over time. Albeit, we cannot state its isotopic composition with confidence, the measured δ15N of unconverted and converted samples were in a similar range throughout the experiments (−28.8 to + 66.3, and −32.7 to + 140.0 for NH2OH-derived and direct N2O, respectively). Thus, 15N accumulating in the N2O pool contributed a very minor fraction of 15N accumulating in the NH2OH pool. Previous studies demonstrate that N2O production during NH3 oxidation in enrichment culture from oceanic water samples, enrichments, and N. maritimus only contribute up to two parts per thousand of NO2− produced (29). A similar rate of N2O production by N. maritimus cells during our experiments would yield an estimated 70 nM N2O over the course of our entire experiments. Because the N2O concentrations in the unconverted samples were below detectable levels, we conclude that any direct N2O produced in our experiments would not affect the NH2OH isotopic analysis.

The isotopic signature of N2O produced by AOA strongly indicated that it is a product of NH3 oxidation and not from reduction of NO2− (28). In addition, C2H2 (∼10%) is known to inhibit N2O reductase but not nitrite reductase (NirK) or nitrous oxide reductase (NOR) activities of nitrifier denitrification pathways in AOB (30, 31). In our 15N tracer experiments, the decline of NH2OH-derived 15N2O accumulation after addition of 0.1% C2H2, indicated that the 15N2O is derived from oxidation of 15NH3 and not from reduction of 15NO2− (Fig. 4A). We also note the formal possibility that exogenously added NH2OH could be converted chemically or biologically forming short-lived nitrogen radicals, such as nitroxyl (HNO•), nitrogen monoxide (NO•), or nitrosyl (NO+), all of which under O2 limitation could undergo further reactions yielding N2O to varying degrees (32). N2O generation can also result from biological or chemical conversion of NO2− and NH2OH into N2O (33). However, a role of such cross-reactions involving NH2OH itself as well as nitrogen-free radicals can also be ruled out because addition of C2H2 stops further accumulation of 15N2O in total N2O pool. Together, these results clearly demonstrate that NH2OH is a product of NH3 oxidation in N. maritimus.

We are thus left with a unique enzyme system for the oxidation of NH2OH in the AOA. All data now implicate a variety of unusual proteins, rather than the c-type cytochrome system of NH2OH oxidation and respiration in the AOB, comprising the remaining oxidative and energy-harvesting steps in the AOA. Apart from providing additional support for the role of a unique biochemistry in global nitrification, continued characterization of this pathway may point to environmental factors, such as specific trace metal availability, limiting or promoting nitrification in different marine and terrestrial provinces.

Methods

Culture Conditions and Cell Harvesting.

All physiological experiments were carried out with N. maritimus strain SCM1 in Hepes-buffered synthetic crenarchaeota medium (SCM) prepared as described (16). C2H2 was produced from barium carbide (BaC2) as described by Hyman and Arp (34). Other reagents, such as NH4Cl, NH2OH, and ATU were research-grade products and were obtained from Sigma. N. maritimus cells were grown to midlog phase (∼550–650 µM NO2− accumulated) and were concentrated by filtration onto nylon membrane filters (Whatman; 47 mm diameter, 0.2 µm pore size; 7402-004) using a vacuum manifold system at 600 mm Hg pressure. The N. maritimus cells harvested in this fashion actively metabolized NH3 for at least 8 h, enabling short-term assays to be conducted. Multiple liters of N. maritimus cultures could be filtered simultaneously and the nylon membranes with concentrated cells served as solid support for the experimental incubations. The N. maritimus cells on the nylon membranes were incubated in SCM with either NH4+ or NH2OH added as a substrate.

NH3- and NH2OH-Dependent O2 Uptake Measurements.

Rates of NH3 and NH2OH-dependent O2 uptake of the N. maritimus cells adsorbed onto the nylon membrane filters were measured with a Clark-type O2 electrode (Yellow Springs Instrument) mounted in an all-glass, water-jacketed reaction vessel (18 mL volume) and operated at 30 °C. All measurements were carried out in NH4+-free SCM media with added NH4+ or NH2OH (200 µM each).

Determination of NH2OH, NO2−, N2O and Protein Concentration.

NH2OH in SCM was oxidized to nitrous oxide (N2O) by the addition of Fe (III) as described (25) and with a minor modification. In our study, the FeAc reagent consisted of 8% (wt/vol) colloidal iron oxide and 6% (vol/vol) glacial acetic acid. This modification adjusted the pH of the sample below 1.4 and assured complete conversion of NH2OH to N2O. The FeAc reagent (1 mL) was injected into 20 mL amber glass serum bottles sealed with Teflon caps containing 2 mL of sample and the bottles were mixed thoroughly. After 1 h incubation at 30 °C, saturated NaCl solution (1 mL) was injected into the sealed bottles to displace the N2O in the liquid phase into the headspace. The bottles were then flash frozen on dry ice and stored upside down until further analysis. The N2O gas in the headspace was measured by gas chromatography using a thermal conductivity detector. Samples were analyzed before and after incubation with FeAc reagent to determine if any N2O accumulated during NH2OH oxidation before incubation with FeAc reagent. The conversion of NH2OH to N2O proceeded in a 2:1 stoichiometry and was above 95% in a concentration range of 1 µM to 1 mM NH2OH. Neither NH4+ nor NO2− interfered with the conversion and quantification of NH2OH.

NO2− concentration was determined with the Griess reagent (sulfanilamide and N-naphthylethylenediamine) as described (35). The rate of NO2− accumulation has been shown previously to be proportional to the density of N. maritimus cell culture (16) and was used as an indicator of growth stages.

Protein concentrations of N. maritimus cells adsorbed onto the filter were determined with the micro BCA protein assay kit from Pierce after protein solubilization at 60 °C for 60 min.

ATP Measurements.

For ATP measurements, the N. maritimus cultures were grown to midlog phase and filtered using the manifold setup. The filters carrying the N. maritimus cells were immersed in NH4+-free SCM in a serum vial capped with a gray-butyl rubber stopper. The bottles were purged with argon gas and cells were allowed to incubate for 2 h to deplete their endogenous ATP levels, allowing detection of newly synthesized ATP upon addition of the substrates. After 2 h of anaerobic treatment, identical filter pieces were cut and distributed into wells of a white 96-well assay plates (White w/lid, tissue culture-treated; BD Biosciences). The plate wells contained O2-saturated SCM with (i) no substrate, (ii) 200 µM NH4+, or (iii) 200 µM NH2OH. ATP accumulation was measured over a time course using a commercial kit based on the luciferase enzyme activity (BactTiter Glo; Promega). To detect ATP generation, 100 µL of the reagent was added per well, incubated 5 min, and the bioluminescence was measured with a multifunction plate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan) with 1-s integration and 10-ms settle time. Statistical differences in ATP values between NH2OH and NH4+ or no substrate were evaluated using Student’s t test. An appropriate ATP standard curve was used to estimate the concentration of ATP in the samples. Samples for NO2− determination were collected before addition of ATP reagent and analyzed as described above.

Detection of NH2OH Formation in N. maritimus Cells.

Natural abundance NH4Cl and NH2OH (200 µM each) were added to SCM containing N. maritimus cells adsorbed onto the nylon membrane filters. The bottles were incubated in the dark at 30 °C. Samples were taken at 20-min intervals for determination of NO2−, N2O concentrations, and isotopic compositions of NH2OH and NO2−. A total of 20 µM 15NH4Cl (Cambridge Isotopes; 99 atom % 15N) was added at 60-min time point and 0.1% C2H2 was added at 120-min time point. NO2− concentration was determined by Griess reagent as described above.

Total NH2OH was determined by GC-thermal conductivity detector (TCD) after conversion to N2O as described above. Isotopic composition of N2O was determined using a continuous flow ThermoFinnigan DeltaPlus stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo) coupled to a Precon (Thermo) and Gasbench II (Thermo) relative to N2O and NO3− standards as described previously (36, 37). Even though the δ15N/14N in N2O pools and the AT% 15N/14N increased during incubations, the rapid disappearance of NH2OH caused the µM 15N-NH2OH concentrations to decrease over time. Hence µM 15N-NH2OH concentrations were calculated from AT % excess 15N/14N values. The AT % excess 15N and µM concentrations of 15NH2OH are calculated as defined below:

i) AT % 15N excess in a sample = AT % 15N in labeled NH2OH pool of sample – AT % natural abundance 15N in unlabeled NH2OH pool at the beginning of the experiment; and

ii) µM 15N-NH2OH = (µM total NH2OH)/(AT % 15N excess in a sample × 100).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Myrold for valuable discussion on the stable isotope tracer experiment results. This work was funded by the US Department of Agriculture (Grant 2005-35319), by the Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station, and by the National Science Foundation (MCB-0604448 and MCB-0920741).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1214272110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Ingalls AE, Könneke M, Stahl DA. Cultivation of a thermophilic ammonia oxidizing archaeon synthesizing crenarchaeol. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10(3):810–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatzenpichler R, et al. A moderately thermophilic ammonia-oxidizing crenarchaeote from a hot spring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(6):2134–2139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708857105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Könneke M, et al. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature. 2005;437(7058):543–546. doi: 10.1038/nature03911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehtovirta-Morley LE, Stoecker K, Vilcinskas A, Prosser JI, Nicol GW. Cultivation of an obligate acidophilic ammonia oxidizer from a nitrifying acid soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(38):15892–15897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107196108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tourna M, et al. Nitrososphaera viennensis, an ammonia oxidizing archaeon from soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(20):8420–8425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013488108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arp DJCPS, Chain PS, Klotz MG. The impact of genome analyses on our understanding of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:503–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arp DJ, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Hommes NG. Molecular biology and biochemistry of ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas europaea. Arch Microbiol. 2002;178(4):250–255. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker CB, et al. Nitrosopumilus maritimus genome reveals unique mechanisms for nitrification and autotrophy in globally distributed marine crenarchaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(19):8818–8823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913533107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallam SJ, et al. Genomic analysis of the uncultivated marine crenarchaeote Cenarchaeum symbiosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(48):18296–18301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blainey PC, Mosier AC, Potanina A, Francis CA, Quake SR. Genome of a low-salinity ammonia-oxidizing archaeon determined by single-cell and metagenomic analysis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e16626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nunoura T, et al. Insights into the evolution of Archaea and eukaryotic protein modifier systems revealed by the genome of a novel archaeal group. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(8):3204–3223. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spang A, et al. Distinct gene set in two different lineages of ammonia-oxidizing archaea supports the phylum Thaumarchaeota. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18(8):331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim BK, et al. Genome sequence of an ammonia-oxidizing soil archaeon, “Candidatus Nitrosoarchaeum koreensis” MY1. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(19):5539–5540. doi: 10.1128/JB.05717-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosier AC, Allen EE, Kim M, Ferriera S, Francis CA. Genome sequence of “Candidatus Nitrosopumilus salaria” BD31, an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from the San Francisco Bay estuary. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(8):2121–2122. doi: 10.1128/JB.00013-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosier AC, Allen EE, Kim M, Ferriera S, Francis CA. Genome sequence of “Candidatus Nitrosoarchaeum limnia” BG20, a low-salinity ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from the San Francisco Bay estuary. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(8):2119–2120. doi: 10.1128/JB.00007-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martens-Habbena W, Berube PM, Urakawa H, de la Torre JR, Stahl DA. Ammonia oxidation kinetics determine niche separation of nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria. Nature. 2009;461(7266):976–979. doi: 10.1038/nature08465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lees H. Hydroxylamine as in intermediate in nitrification. Nature. 1952;169:156–157. [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Bruijn P, Van de Graaf AA, Jetten MSM, Robertson LA, Kuenen JG (1995) Growth of Nitrosomonas europaea on hydroxylamine. FEMS Microbiol Lett 125(2–3):179–184.

- 19.Hyman MR, Wood PM. Suicidal inactivation and labelling of ammonia mono-oxygenase by acetylene. Biochem J. 1985;227(3):719–725. doi: 10.1042/bj2270719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hofman T, Lees H. The biochemistry of the nitrifying organisms. IV. The respiration and intermediary metabolism of Nitrosomonas. Biochem J. 1953;54(4):579–583. doi: 10.1042/bj0540579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Offre P, Prosser JI, Nicol GW. Growth of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in soil microcosms is inhibited by acetylene. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;70(1):99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Böttcher S, Koops H-P. Growth of lithotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria on hydroxylamine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;122:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basant Bhandari DJDN. Ammonia and O2 uptake in relation to proton translocation in cells of Nitrosomonas europaea. Arch Microbiol. 1979;122(3):249–255. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramaiah A, Nicholas DJ. The synthesis of Atp and the incorporation of 32p by cell-free preparations from Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964;86:459–465. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(64)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butler JH, Gordon LI. Rates of nitrous oxide production in the oxidation of hydroxylamine by iron(II1) Inorg Chem. 1986;25:4573–4577. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyman MR, Arp DJ. 14C2H2- and 14CO2-labeling studies of the de novo synthesis of polypeptides by Nitrosomonas europaea during recovery from acetylene and light inactivation of ammonia monooxygenase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(3):1534–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frijlink MJ, Abee T, Laanbroek HJ, de Boer W, Konings WN. The bioenergetics of ammonia and hydroxylamine oxidation in Nitrosomonas europaea at acid and alkaline pH. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157(2):194–199. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santoro AE, Buchwald C, McIlvin MR, Casciotti KL. Isotopic signature of N(2)O produced by marine ammonia-oxidizing archaea. Science. 2011;333(6047):1282–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.1208239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Löscher CRKA, Könneke M, LaRoche J, Bange HW, Schmitz HW. Production of oceanic nitrous oxide by ammonia-oxidizing archaea. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:2419–2429. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berg P, L Klemedtsson, Rosswall T (1982) Inhibitory effect of low partial pressures of acetylene on nitrification. Soil Biol Biochem 14(3):301–303.

- 31.Bateman EJ, Baggs EM. Contributions of nitrification and denitrification to N2O emissions from soils at different water-filled pore space. Biol Fertil Soils. 2005;41(6):379–388. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moir JW, Crossman LC, Spiro S, Richardson DJ. The purification of ammonia monooxygenase from Paracoccus denitrificans. FEBS Lett. 1996;387(1):71–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hooper AB, Terry KR. Hydroxylamine oxidoreductase of Nitrosomonas. Production of nitric oxide from hydroxylamine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;571(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(79)90220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hyman MR, Arp DJ. The small-scale production of [U-14C]acetylene from Ba14CO3: Application to labeling of ammonia monooxygenase in autotrophic nitrifying bacteria. Anal Biochem. 1990;190(2):348–353. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90206-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hageman RH, Hucklesby DP. Nitrate reductase in higher plants. Methods Enzymol. 1971;23:491–503. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sansone FJ, Popp BN, Rust TM. 1997. Stable carbon isotopic analysis of low-level methane in water and gas. Anal Chem (69):40–44.

- 37.Sigman DM, et al. A bacterial method for the nitrogen isotopic analysis of nitrate in seawater and freshwater. Anal Chem. 2001;73(17):4145–4153. doi: 10.1021/ac010088e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.