Abstract

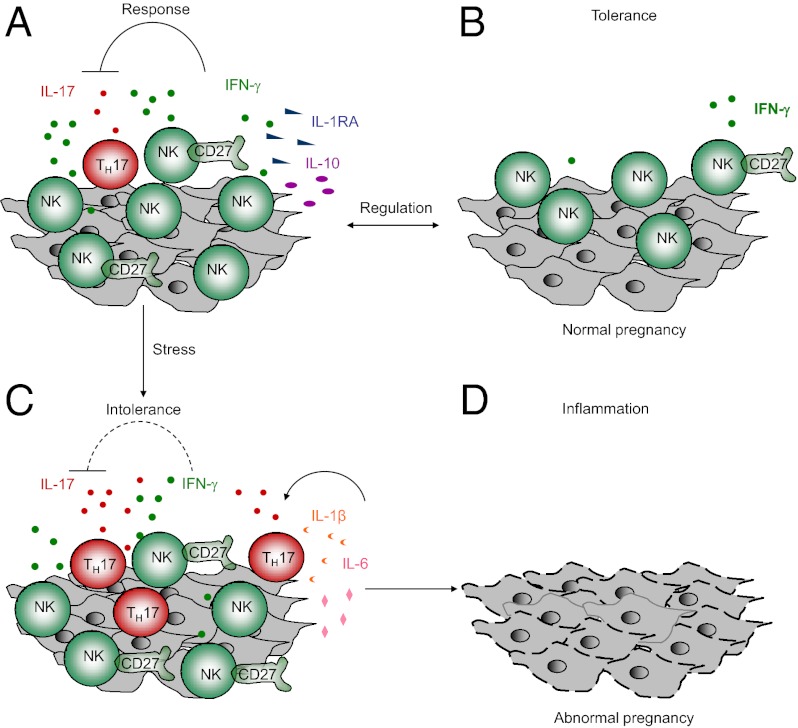

Natural killer (NK) cells accumulate at the maternal–fetal interface in large numbers, but their exact roles in successful pregnancy remain poorly defined. Here, we provide evidence that TH17 cells and local inflammation can occur at the maternal–fetal interface during natural allogenic pregnancies. We found that decidual NK cells promote immune tolerance and successful pregnancy by dampening inflammatory TH17 cells via IFN-γ secreted by the CD56brightCD27+ NK subset. This NK-cell–mediated regulatory response is lost in patients who experience recurrent spontaneous abortions, which results in a prominent TH17 response and extensive local inflammation. This local inflammatory response further affects the regulatory function of NK cells, leading to the eventual loss of maternal-fetal tolerance. Thus, our data identify NK cells as key regulatory cells at the maternal–fetal interface by suppressing TH17-mediated local inflammation.

Keywords: regulatory NK cells, fetomaternal tolerance

During pregnancy, allogeneic fetal cells invade the maternal decidua but they are protected from the maternal immune system. This invasion of extraembryonic trophoblasts does not harm gestation during normal pregnancy; it establishes tolerance at the maternal–fetal interface (1), (2), although the mechanism of such tolerance is not clear. In addition, inflammatory responses induced by a variety of mechanisms can result in embryo loss, but mild inflammation can be effectively controlled through regulatory mechanisms to maintain successful pregnancy (3). Thus, suppression of strong inflammatory responses is essential to ensure normal pregnancy (4, 5), although the mechanisms involved in regulating local inflammation without compromising overall maternal immunity during a successful pregnancy remain unknown.

Multiple mechanisms are potentially involved in promoting immune tolerance during pregnancy. For example, TH2 cytokine polarization (6–9), the expression of the Fas ligand on trophoblast cells (10), and the inhibition of complement activation (11) are crucial for ensuring tolerance at the maternal–fetal interface. In addition, a delicate balance exists between inhibitory (PD-L1, Stat3, and TGF-β1) and stimulatory (CD80 and CD86) signals during the establishment of immune privilege (12–18). Furthermore, studies have shown that galectin-1 (19) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (20) play pivotal roles in maternal–fetal tolerance. Several types of immune cells, such as CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, are also essential in the generation of maternal–fetal tolerance in mice and humans (7, 21–24). Furthermore, natural killer (NK) T cells and immature dendritic cells have been reported to promote the expansion of Treg cells that confer protection of the fetus (19).

Despite considerable progress, many questions remain unanswered. The most striking feature at the maternal–fetal interface is the accumulation of NK cells, which account for ∼60–90% of immune cells in the decidua in humans during early pregnancy (25–29) and are believed to be critical in maintaining immune balance (4, 5, 25, 26, 30–32). Recent evidence has also shown that decidual NK (dNK) cells play a key role in controlling trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling (33, 34). Although NK cells are an important cell type within the innate immune system and also act as sentinel cells in other models (35–37), their exact function at the maternal–fetal interface remains incompletely defined. Recent studies have reported that CD27, which belongs to the TNF receptor family, is an important marker in distinguishing different subsets of NK cells (38, 39). Based on the surface density of CD27 and CD11b, murine NK cells can be classified into four subsets that represent their different maturation stages (40). We previously demonstrated that the expression of CD27 and CD11b can also identify distinct populations of human NK cells (39). Interestingly, we found a large number of CD27+ NK cells in the deciduas; these cells are an important source of cytokines and show limited cytotoxicity. However, the functions of this subset of NK cells in maternal–fetal tolerance have not yet been identified.

Here, we studied the function of dNK cells in successful pregnancy and examined NK subsets, their distribution, and cytokine secretion profiles. We provide evidence that dNK cells possess a unique ability to maintain immune tolerance and suppress inflammation by antagonizing TH17 cells that exist in natural allogeneic pregnancies at the maternal–fetal interface. Moreover, the balance between NK cells and TH17 cells is lost in patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Our results suggest that NK cells serve as pivotal sentinel cells that control local inflammation and maintain tolerance at the maternal–fetal interface.

Results

Human CD56brightCD27+ NK Cells Preferentially Accumulate in the Decidua During the First Trimester.

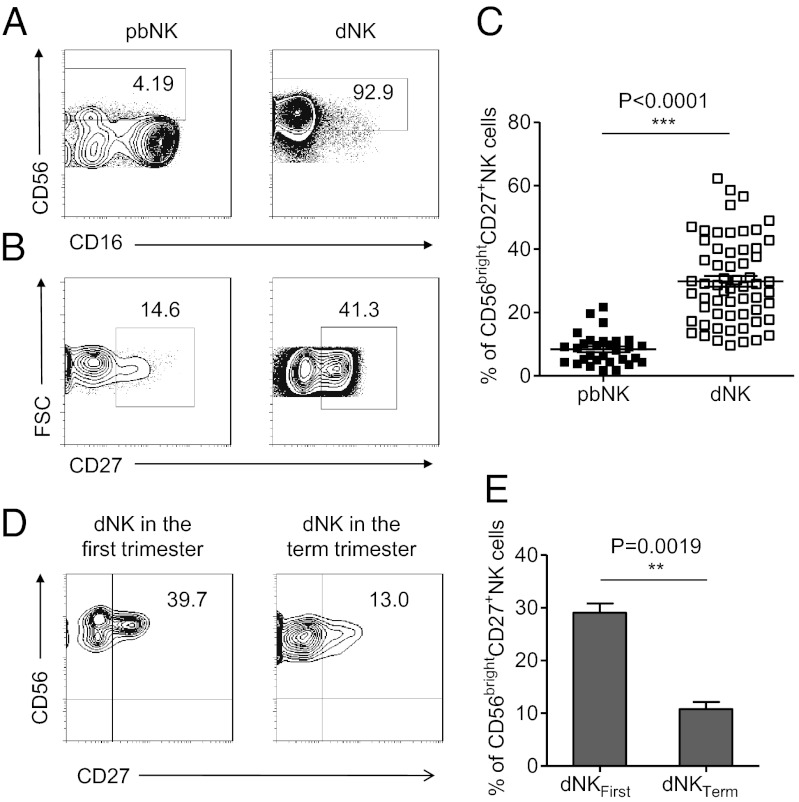

In contrast to NK cells in the peripheral blood, which accounted for a small fraction of the total lymphocytes (∼10%), NK cells were the dominant cell type in the decidua during normal pregnancy (∼70%) (4, 25, 33, 41). Interestingly, >90% of the NK cells in the decidua were CD56bright NK cells, whereas less than 10% of the peripheral NK cells were CD56bright NK cells (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

CD56brightCD27+ NK cells present in large numbers in human deciduas of the first trimester. (A) Representative density plots showing an analysis of CD56bright NK cells in gated CD56+CD3− NK cells isolated from peripheral blood (pbNK) and decidua in the first trimester (dNK). (B) Representative density plots showing an analysis of CD27+ NK cells in gated CD56bright pbNK and CD56bright dNK. (C) Percentages of CD56brightCD27+ NK cells in gated CD56bright pbNK and CD56bright dNK. n = 30 and 60 for pbNK and dNK, respectively. (D) Representative density plots showing an analysis of CD27 in gated CD56brightCD3− NK cells isolated from decidua in the first trimester and in the term trimester. (E) Percentages of CD56brightCD27+ NK cells in dNK in the first trimester and dNK in the term trimester. n = 62 and 6 for dNK in the first trimester and dNK in the term trimester, respectively. The data in C and E are presented as the means ± SEM.

Because CD27 expression is known to define specific subsets of NK cells (38–40), we compared the CD27 expression on CD56bright dNK cells to that on peripheral NK cells, and we found that a much higher proportion of dNK cells were CD56brightCD27+ NK cells (29.84 ± 1.713%) (Fig. 1 B and C). We then investigated the kinetics of NK cells accumulating at the maternal–fetal interface during pregnancy and confirmed that CD56brightCD27+ NK cells accumulated specifically during the first trimester. As the pregnancy progressed, the percentage of this CD56brightCD27+ subset decreased significantly in the first trimester compared with the subset in the term trimester (Fig. 1 D and E). Thus, the CD56brightCD27+ NK subset was well represented in the first trimester of pregnancy.

CD56brightCD27+ NK Cells Show Activated Phenotype and Are the Main Source of Cytokines.

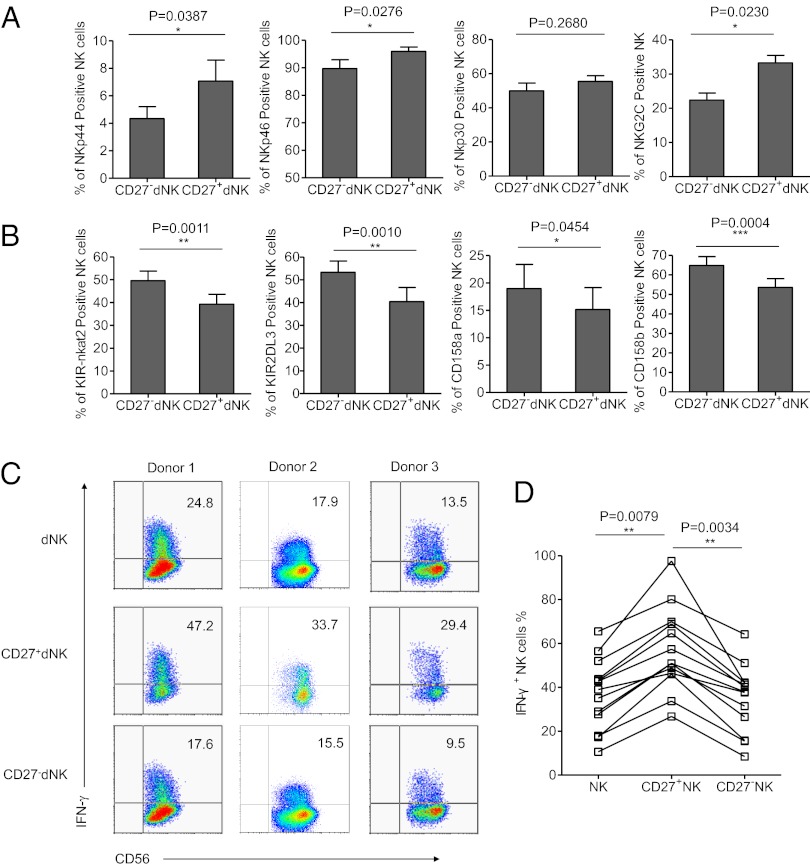

Due to the differential expression of activating and inhibitory receptors, NK cells are phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous (42, 43). We compared the phenotypes of the CD27+ dNK and CD27− dNK cells and found the CD27+ dNK subset to express fewer inhibitory receptors, such as CD158a, CD158b, KIR-nkat2, and KIR2DL3, and more activating receptors, such as NKp44, NKp46, and NKG2C. These findings indicate that the human CD27+ dNK cell subset displays a more activated phenotype than CD27− dNK cells (Fig. 2 A and B). Comparison of CD27+ dNK cells and CD27+ pbNK cells showed limited differences in the expression of NK receptors, suggesting that the CD27+ pbNK cells and CD27+ dNK cells were phenotypically similar, despite striking differences their relative abundance (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

CD56brightCD27+ NK are activated and are the main source of cytokines. (A and B) Percentage analyses of activating receptors and inhibitory receptors on gated CD27+CD56+CD3− dNK cells and CD27−CD56+CD3− dNK cells. n = 10 for KIR-nkat2, KIR2DL3, and NKG2C; 11 for NKp44, CD69, CD94, and NKG2A; 12 for NKp46; 13 for CD158a and CD158b; and 15 for NKp30. Data in A and B are presented as means ± SEM. (C) Representative density plots of IFN-γ expression on gated CD56+CD3−, CD27+CD56+CD3−, and CD27−CD56+CD3− dNK cells of the first trimester. (D) Percentages analyses of IFN-γ+ cells in dNK cells, CD27+ dNK cells, and CD27− dNK cells. n = 13 for each group.

Given that dNK cells are activated cells and lack significant cytotoxic activity (30, 44, 45), we hypothesized that their main function might be cytokine secretion. We sorted dNK cells using FACS and stimulated them with phorbol 12-myrstate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin in vitro; we found that IFN-γ was highly produced by dNK cells from multiple donors. Furthermore, the CD56brightCD27+ NK subset secreted much higher levels of IFN-γ than the CD27− subset. Approximately one-half of the CD27+ dNK cells (57.07 ± 5.301%) were IFN-γ–secreting cells (Fig. 2 C and D). Thus, the main source of IFN-γ was the CD56brightCD27+ dNK cell subset.

NK Cells Control TH17 Cells and Maintain Tolerance During Successful Allogeneic Pregnancy.

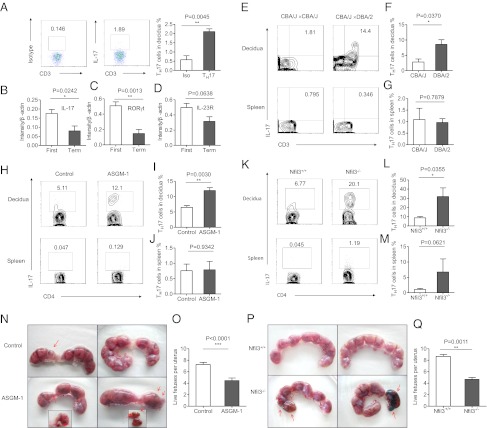

T cells are also present in the decidua, where they can recognize alloantigens and become inflammatory. Previous reports have shown that TH17 cells represent a barrier to the induction of tolerance in transplantation and pregnancy (17, 46, 47). To investigate the presence of TH17 cells, we first assayed the IL-17–producing T cells present in the decidua during different phases of pregnancy. Of the CD3+CD4+ T cells in the normal decidua during the first trimester, we found that 2.107 ± 0.1521% of these cells secreted IL-17 (Fig. 3A). We also found that the mRNA expression levels of TH17-related factors (IL-17, RORγt, and IL-23R) were higher in first-trimester decidual lymphocytes than in full-term lymphocytes (Fig. 3 B–D). Thus, a small population of TH17 cells exists during the first trimester of normal human pregnancy.

Fig. 3.

NK cells control TH17 cells in normal allogeneic pregnancy. (A) Representative density plots showing analysis of IL-17–secreting cells in gated CD3+CD4+ T cells in normal deciduas in the first trimester. (B) RNA levels of IL-17A expressions in decidual lymphocytes of the first trimester and the term trimester. n = 8 and 4, respectively. (C) RNA levels of RORγt expressions in decidual lymphocytes of the first trimester and the term trimester. n = 8 and 4, respectively. (D) RNA levels of IL-23R expressions in decidual lymphocytes of the first trimester and the term trimester. n = 8 and 4, respectively. (E) Representative density plots showing analysis of IL-17–secreting cells in gated CD3+ T cells in deciduas and spleen from allogeneic pregnant CBA/J females and syngeneic pregnant CBA/J females at gd 14.5. (F and G) Percentage analysis of IL-17+ cells in gated CD4+T cells from spleen and deciduas of allogeneic pregnant CBA/J females and syngeneic pregnant CBA/J females. n = 3 and 5 for allogeneic mating and syngeneic mating, respectively. (H) Representative density plots showing analysis of IL-17–secreting cells in gated CD4+ T cells in deciduas and spleen from allogeneic pregnant CBA/J females treated with PBS or anti–ASGM-1. NK cells were deleted by injecting 30 μL of ASGM-1 in 200 μL of PBS through the tail vein at gd 0.5, 4.5, and 8.5 each time. The control groups were injected with 200 μL of PBS at the same time point as anti–ASGM-1 injection. Both groups were euthanized at gd 14.5 to examination the IL-17+ expression and fetal resorption rate. (I and J) Percentage analysis of IL-17+ cells in gated CD4+T cells from spleen and deciduas of allogeneic pregnant CBA/J females with treatment of PBS or anti–ASGM-1. n = 5 for both groups. (K) Representative density plots showing analysis of IL-17–secreting cells in gated CD4+ T cells in deciduas and spleens from allogeneic pregnant Nfil3−/− females or Nfil3+/+ females. Both group were mated with BALB/c mice and killed at gd 14.5. (L and M) Percentage analysis of IL-17+ cells in gated CD4+ T cells from spleens and deciduas of allogeneic pregnant Nfil3−/− females or Nfil3+/+ females. n = 4 for both groups. (N and O) Representative picture of the number of embryos and live fetuses per uterus from allogeneic pregnant CBA/J females treated with PBS or anti–ASGM-1. (P and Q) Representative picture of the number of embryos and live fetus per uterus in allogeneic pregnant Nfil3−/− and Nfil3+/+ mice models.n = 4 for each group. The red arrows indicate embryos that were subject to hemorrhage, ischemia, and necrosis. The data in B–D, F, G, I, J, L, M, O, and Q are presented as the means ± SEM.

To determine whether these TH17 cells were induced following contact with allogeneic antigens, we examined the potential role of TH17 cells in spontaneous embryo loss using a mouse allogeneic pregnancy model. Allogeneic pregnant CBA/J × DBA/2 mice (CBA/J females mated with DBA/2 males) and syngeneic pregnant CBA/J × CBA/J mice were monitored simultaneously. Our data showed that the percentage of TH17 cells among the total CD4+ T decidual cells increased significantly in the allogeneic pregnant CBA/J × DBA/2 mice at gestational day (gd) 14.5, which suggested that maternal T cells can respond to allogeneic fetal antigens and that decidual T cells have the potential to become pathogenic TH17 cells. No differences were observed in the percentages of TH17 cells in the spleens of either group (Fig. 3 E–G). Thus, in the allogeneic pregnancy model, a small population of TH17 cells does exist at the maternal–fetal interface.

To examine whether NK cells play a role in regulating TH17 cells in vivo, we deleted NK cells in pregnant CBA/J mice (allogeneic mating) with anti-asialo GM-1 antibody (ASGM-1) (or PBS) at gd 0.5, 4.5, and 8.5. At gd 14.5, both groups were euthanized, and the deciduas and spleens from each group were collected and analyzed separately. The efficiency and specificity of NK depletion are shown in Fig. S2. The percentage of TH17 cells (IL-17A+CD4+CD3+T) in the deciduas was significantly increased in the NK-cell-depleted group (11.97 ± 0.9273%) compared with the control group (6.497 ± 0.5792%), suggesting a key role for NK cells in the suppression of TH17 cells during allogeneic pregnancy (Fig. 3 H and I). No significant differences were found in the spleen cells between the groups (Fig. 3J). We repeated the experiments in an allogeneic model in which Nfil3−/− females mated with BALB/c males, and Nfil3+/+ mice were used as controls. NK cells are absent in the Nfil3−/− mice. Both groups were euthanized at gd 14.5. The percentage of TH17 cells in the decidua of Nfil3−/− mice was significantly higher than that in the Nfil3+/+ control group, further demonstrating that NK cells control TH17 cells during allogeneic pregnancy (Fig. 3 K–M). Moreover, the number of live allogeneic fetuses per pregnancy decreased in both the CBA/J allogeneic mouse model following NK cell depletion and in Nfil3−/− mice, suggesting that without NK cells, TH17 cells may have induced and caused fetal loss (Fig. 3 N–Q).

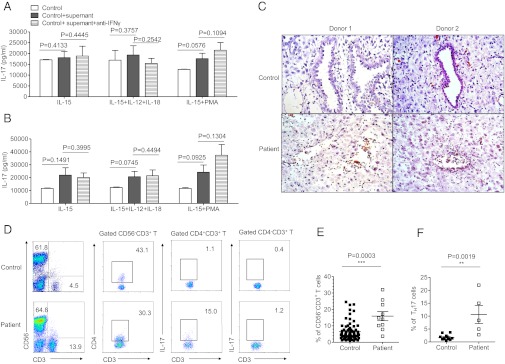

NK Cells Inhibit TH17 Cells Through an IFN-γ–Dependent Mechanism.

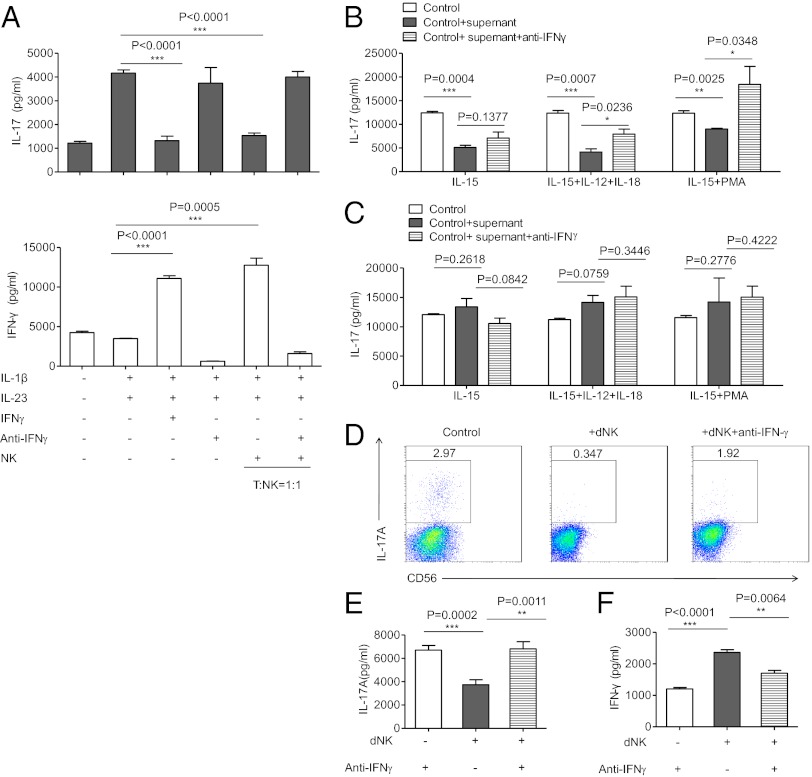

Given the finding that CD56brightCD27+ dNK cells readily secrete high levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 2 C and D) and that IFN-γ can inhibit the polarization of TH17 cells in mouse models (48, 49), we hypothesized that dNK cells may control TH17 cell polarization at least in part through the production of IFN-γ. First, we evaluated the effect of IFN-γ on human TH17 cell differentiation in vitro. We cultured freshly isolated CD4+ peripheral T lymphocytes with or without the recombinant cytokines necessary for TH17 polarization, and we then quantified the production of IL-17 and IFN-γ by ELISA. In medium supplemented with IL-1β and IL-23, a TH17 phenotype was induced, as indicated by the production of IL-17A. Similar to the results obtained in mice (48, 49), the expansion of human TH17 cells was inhibited by the addition of IFN-γ and was reinduced when IFN-γ was neutralized, which suggests that IFN-γ inhibits TH17 differentiation in humans. Second, we evaluated the effect of IFN-γ produced by activated NK cells on human TH17 cell expansion. We obtained activated NK cells by isolating peripheral NK cells from human donors and then preactivated them for 12 h with IL-12 to induce IFN-γ expression. These NK cells were then added to the TH17 polarization system, and we found that TH17 cell differentiation was inhibited when NK cells were added but was reinduced when IFN-γ was inhibited (Fig. 4A and Fig. S3). These data show that activated human NK cells down-regulate TH17 differentiation through the production of IFN-γ.

Fig. 4.

NK cells inhibit TH17 cells through an IFN-γ–dependent mechanism. (A) ELISA of IL-17A and IFN-γ in cell-free supernatants of cultured T cells. The data are representative of five experiments. CD4+T cells were cultured for 6 d in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in complete RPMI medium 1640 and were activated with TH17 expansion condition. Purified NK cells from the same human donor were preactivated by IL-12 (100 U/mL). Culture supernatants were collected after 6 d of culturing and analyzed by ELISA. (B) ELISA of IL-17A in cell-free supernatants of cultured T cells with supernatant from dNK cells. The data are representative of three experiments. CD56+CD3− dNK cells and non-NK mononuclear cells were separated and cultured in different conditions for 60 h. The supernatant from each culturing was collected and added into the system of TH17 expansion. After 6 d of culturing, each supernatant of the TH17 system was collected and the IL-17 concentration was quantified by ELISA. (C) ELISA of IL-17A in cell-free supernatants of cultured T cells with supernatant from non-NK decidual mononuclear cells. (D) Representative density plots of IL-17A expression in a TH17 expansion system in gated CD56−CD4+T cells. Purified dNK cells from the first trimester were added to the TH17 expansion system at a ratio of dNK:T = 5:1. Cells were collected after 6 d of culturing and recultured under monensin (10 μg/mL), ionomycin (1 μg/mL), and PMA (50 ng/mL) for 4 h in complete RPMI medium 1640. Then, cells were collected for intracellular cytokine staining for IL-17A. (E and F) ELISA of IL-17A and IFN-γ in cell-free supernatants of the cultured dNK-T system. Supernatants were collected after 6 d of culturing. The data are representative of six experiments. The data are presented as the means ± SEM.

To verify whether the dNK-cell–derived IFN-γ acts directly on TH17 cells, we obtained the deciduas from first-trimester normal pregnancies, sorted CD56+CD3− dNK cells, and cultured these cells under different conditions for 60 h. Then, the supernatant from each culture was collected and added to the TH17 polarization system. After 6 d of culture, the supernatants were collected, and the concentrations of IL-17 were quantified by ELISA. We found that the supernatants from normal dNK cells inhibited TH17 expansion. In contrast, the supernatants from non-NK cells did not (Fig. 4 B and C). Furthermore, we also purified dNK cells and added them directly into TH17 induction cultures. After 6 d of coculturing, the cells were briefly stimulated with ionomycin (1 μg/mL) and PMA (50 ng/mL) in the presence of monensin (10 μg/mL) for 4 h, followed by intracellular cytokine staining for IL-17A. The supernatant from the culture system was also collected and analyzed by ELISA. Our data showed that dNK cells strongly inhibited development of TH17 cells. The addition of neutralizing anti–IFN-γ was able to rescue the inhibition of TH17 induction (Fig. 4 D–F). Collectively, these results indicate that dNK cells directly antagonize TH17 cells through an IFN-γ–dependent mechanism.

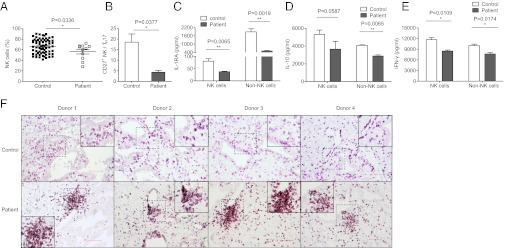

NK Cells Are Altered and Fail to Inhibit TH17 Cells in Patients with Recurrent Abortions.

We obtained decidual tissues from patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions and assessed whether there were changes in the NK cells. We observed that the percentage of NK cells decreased significantly in the deciduas of these patients (56.34 ± 4.379%) compared with the deciduas from healthy pregnancies (66.06 ± 1.673%) (Fig. 5A). Given that the CD27+ NK subsets were the main source of IFN-γ in normal pregnancies and inhibited TH17 expansion (Figs. 2 and 3), we then investigated the ratio of CD27+ NK cells to TH17 cells and observed that this ratio was significantly decreased in this pathological state (Fig. 5B). We further investigated additional cytokines, such as IL-10 and IL-1RA, which are secreted by dNK cells. NK cells from normal deciduas secrete large amounts of IL-10, which is the key cytokine responsible for suppressing TH17 cells (50). IL-1RA, which is a natural inhibitor of proinflammatory IL-1β, has also been found in the supernatants of normal dNK cells. However, the expression of these three cytokines (IL-1RA, IL-10, and IFN-γ) was significantly decreased in the dNK cells of patients who aborted (Fig. 5 C–E), suggesting that the regulation of NK cells in patients with recurrent abortions is impaired. To identify the distribution of dNK cells in this pathological state, we analyzed CD56+ cells by immunohistochemistry. The NK cells in normal deciduas were consistently uniformly distributed, whereas these cells were concentrated in the deciduas of patients who aborted (Fig. 5F). These results suggest that NK cells are abnormal in the deciduas of patients who aborted; we observed not only different percentages of NK cells and levels of cytokine secretion but also abnormal localization of NK cells in these decidual tissues.

Fig. 5.

NK cells are abnormal in recurrent spontaneous abortion. (A) Percentages analysis of CD56+CD3− dNK cells from normal decidua and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion. n = 67 and 11 for normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion, respectively. (B) Percentages analysis of the ratio between CD27+CD56+CD3− dNK cells and TH17 cells from normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion. n = 9 and 4, respectively. (C–E) ELISAs of IL-1RA, IL-10, and IFN-γ in cell-free supernatants of cultured dNK cells and decidual non-NK mononuclear cells. Decidual NK cells and non-NK cells were cultured in the presence of IL-15 (10 ng/mL) for 60 h in 96-well flat-bottomed plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in complete RPMI medium 1640. Data in A–E are presented as means ± SEM. (F) Immunohistochemistry for CD56+ cells in paraffin sections of normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Dashed squares indicate matching areas that contain CD56+ cell clusters in each row that were magnified in the other frames and presented in the corner insets. (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

We demonstrated that the supernatants from normal dNK cells inhibited TH17 expansion through an IFN-γ–dependent mechanism. (Fig. 4 B–F and Fig. S3). To verify the direct regulatory role of dNK cells in the pathological state, we next collected the supernatants from dNK cell and decidual non-NK mononuclear cell cultures from patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions under different cytokine conditions and added them to the TH17 cell polarization system. In contrast to normal NK cells, the supernatants from the abnormal NK cells did not effectively suppress the expansion of TH17 cells (Fig. 6 A and B). These data suggest that NK cells from patients who aborted are abnormal and no longer inhibit TH17 cells.

Fig. 6.

Abnormal NK cells fail to inhibit TH17 cells in recurrent spontaneous abortion. (A) ELISA of IL-17A in cell-free supernatants of cultured T cells with supernatant from dNK cells of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Data are representative of three experiments. CD56+CD3− dNK cells and non-NK mononuclear cells were separated from patients of recurrent spontaneous abortion and cultured in different conditions for 60 h. The supernatant from each culturing was collected and added into the system of TH17 expansion. After 6 d of culturing, each supernatant of the TH17 system was collected and quantified for IL-17 concentration by ELISA. (B) ELISA of IL-17A in cell-free supernatants of cultured T cells with supernatant from non-NK mononuclear cells of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Data are representative of three experiments. (C) H&E staining for deciduas of normal deciduas and recurrent spontaneous abortion. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (D) Representative density plots showing analysis of CD56 and CD3 expressions in lymphocytes, analysis of CD4 and CD3 expression in gated CD56−CD3+ T cells, and analysis of IL-17 expression in gated CD4+CD3+ T cells and CD4−CD3+ T cells isolated from normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion. (E) Percentages of CD56−CD3+ Tcells of lymphocytes isolated from normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion. n = 72 and 10 for normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion, respectively. (F) Percentages of IL-17–secreting cells in the gated CD4+ T cells isolated from normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion. n = 9 and 5 for normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion, respectively. The data in A, B, E, and F are presented as means ± SEM.

To further confirm the NK cell impairment, we obtained decidual tissues from patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions. In the deciduas of patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions, tissue inflammation was obvious, and the endometrial glands were disrupted and infiltrated by inflammatory cells (Fig. 6C). We also found that the proportion of T cells was significantly increased in the deciduas of patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions (15.91 ± 2.761%) compared with those in patients with normal pregnancies (6.500 ± 0.6407%) (Fig. 6 D and E). We then determined whether TH17 cells were altered in the deciduas of patients with abnormal pregnancies. FACS analysis demonstrated that there were increased proportions of IL-17–secreting CD4+ T cells in the deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion patients (10.64 ± 3.510%) compared with those with normal pregnancies (1.707 ± 0.3891%) (Fig. 6F). Importantly, the TH17 cells were the main source of IL-17 among the total T cells, and we found that CD4−CD3+ T cells secreted very little IL-17 (Fig. 6D). Thus, during recurrent spontaneous abortions, increased numbers of TH17 cells and impaired NK cells are present in the decidual tissues.

Expanded TH17 Cells in Decidual Tissues Cause Fetal Loss.

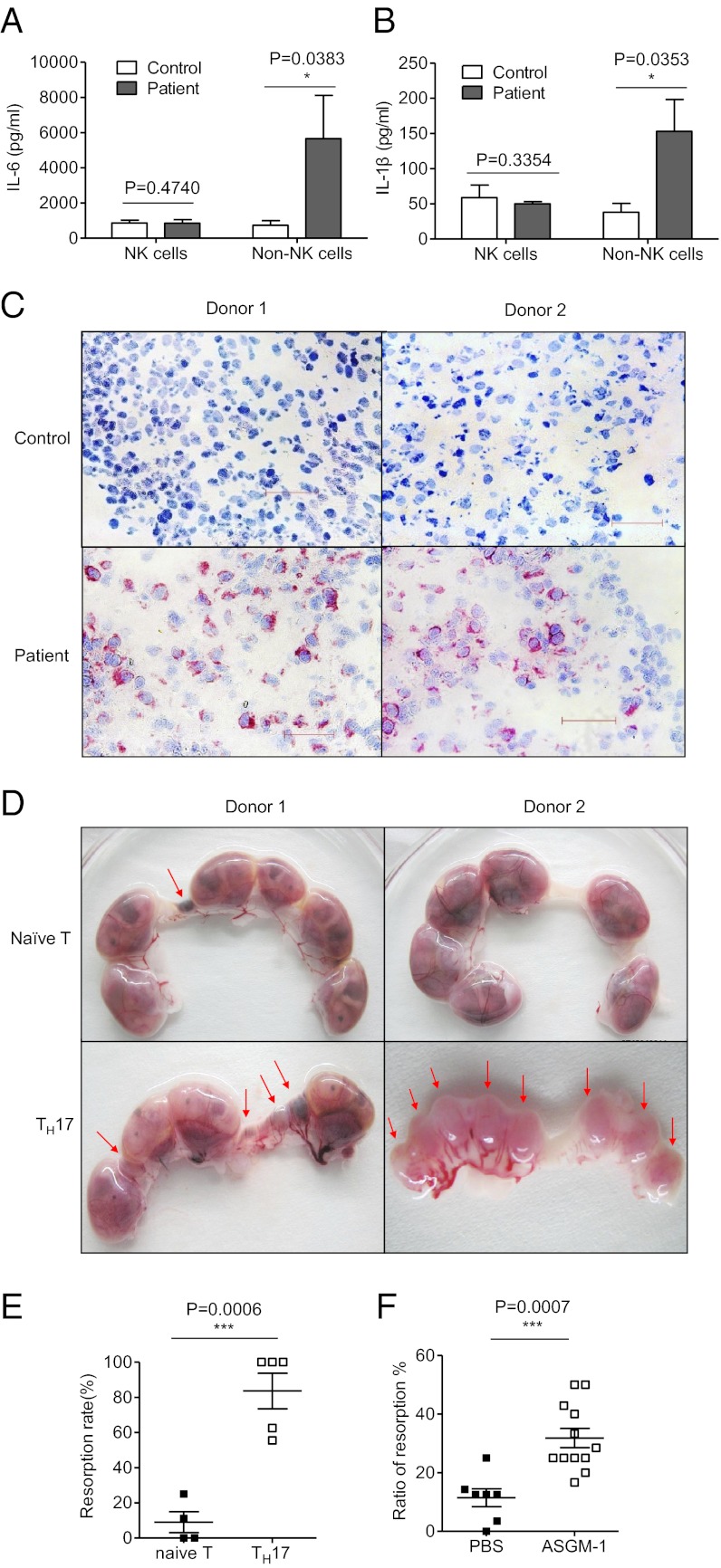

To gain additional insight into the underlying mechanisms, we isolated dNK cells and decidual non-NK mononuclear cells from patients with recurrent abortions and examined the production of a panel of inflammatory cytokines. The secretion of IL-6 and IL-1β was extremely low. However, the non-NK cells from the deciduas of patients who aborted produced high levels of IL-6 and IL-1β (Fig. 7 A and B). Furthermore, using an antibody specific for IL-17, we found that the decidual tissues of patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions were infiltrated by much higher levels of IL-17+ cells (Fig. 7C). The expression of IL-1 and IL-6, cytokines that support the development TH17 cells by non-NK cells in the decidua, suggests extensive local inflammation, which may further affect the function of dNK cells.

Fig. 7.

Prominent TH17 cells in decidua cause severe fetal loss. (A and B) ELISA of IL-6 and IL-1β in cell-free supernatants of cultured dNK cells and decidual non-NK mononuclear cells. Decidual NK cells and non-NK cells were cultured in the presence of IL-15 (10 ng/mL) for 60 h in 96-well flat-bottomed plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in complete RPMI medium 1640. (C) Immunohistochemistry for IL-17A in cryostat sections of normal deciduas and deciduas of recurrent spontaneous abortion followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (D) Representative picture of embryos from naïve T-cell–transferred mice and TH17-cell–transferred mice. Naïve T cells were sorted from C57BL/6 female mice and transferred directly via the tail vein at 1 × 106 per mouse or induced into TH17 cells under conditions for TH17 cell polarization. After 6 d of culturing, these cells were collected and transferred via the tail vein at 1 × 106 per mouse. (E) Analysis of the resorption rate between the naïve T-transferred group and the TH17-transferred group. n = 4 and 5, respectively. (F) Percentage analysis of the resorption rate with or without NK depletion in allogeneic pregnant CBA/J models. n = 7 and 12 for the PBS group and NK-depletion group, respectively. The data in A, B, E, and F are presented as the means ± SEM.

To determine whether there is a relationship between increased frequencies of TH17 cells and fetal loss in vivo, we performed the following experiments using a mouse model. First, naïve T cells were sorted from the spleens of C57BL/6 mice and adoptively transferred into pregnant mice at gd 7.5. In a different group, the sorted naïve T cells were induced to develop into TH17 cells for 6 d and then adoptively transferred into pregnant mice at gd 7.5. The two groups of pregnant mice were euthanized at gd 14.5, and the fetal conditions were examined. We observed that the group with adoptively transferred TH17 cells suffered significant fetal loss; the rate of fetal loss was 83.60 ± 10.10%, which was significantly higher than that of the group that received nonpolarized naïve T cells (Fig. 7 D and E). Experiments using naïve T cells and TH17 cells from EGFP mice further confirmed that TH17 cells could reach to deciduas and be detected even 7 d after passive transferring (Fig. S4). Thus, TH17 cells are highly pathogenic during pregnancy. Moreover, the number of live fetuses per pregnancy decreased in the CBA/J allogeneic pregnant mice following NK cell depletion, which was associated with an increased fetus absorption rate, suggesting that without the regulation of NK cells, TH17 cells expanded and caused fetal loss (Figs. 7F and 3 N and O).

Discussion

One striking feature of normal pregnancy is that a large population of NK cells accumulates at the maternal–fetal interface (26–28). However, the exact immune function of these NK cells remains incompletely defined. Our results demonstrate that dNK cells maintain immune tolerance by antagonizing TH17 cells. IFN-γ is closely involved in this effect, and the main source of IFN-γ is confined to the CD56brightCD27+ dNK subset. Importantly, the inhibition of TH17 cells by these NK cells is contingent upon the absence of local inflammation. We have provided evidence that this regulatory process is critical for successful pregnancy and that NK cells play a key role in the control of local inflammation to ensure optimal fetal development at the maternal–fetal interface.

NK cells are both phenotypically and functionally diverse (42), and they have been shown to have many regulatory functions. TGF-β–secreting NK3 cells down-regulate T-cell activity and play a key role in inhibiting the development of diabetes (51). The recently identified NK22 cells also have important regulatory functions in mucosal immunity (52). Several elegant experiments have revealed that human dNK cells can control trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling by secreting an array of angiogenic factors, chemokines, and cytokines (33, 34, 53). NK cells in the murine decidua have also been shown to be more cytotoxic during episodes of severe inflammation (54). These studies, as well as our previous report (39), have revealed the versatility, complexity, and tissue specificity of NK cells. However, the specific immune function related to the accumulation of dNK cells remains unclear.

Here, we provide evidence that the CD56brightCD27+ NK subset accumulates at the human maternal–fetal interface and plays a key role in controlling local inflammation. In fact, in natural allogenic pregnancies, mild inflammation and low levels of TH17 cells can be developed at the maternal–fetal interface. Our results indicate that one of the functions of NK cells at the maternal–fetal interface is to inhibit local inflammation and maintain immune balance. Additionally, the distribution of this subset differed between the peripheral blood and the decidua, demonstrating that NK cells are tissue-specific and heterogeneous. Moreover, we observed IFN-γ secretion by NK cells and found that IFN-γ could down-regulate human TH17 cell expansion, as demonstrated in mice (48, 49). However, the effects of IFN-γ are complex; results from mice have shown that IFN-γ produced by dNK cells also contributes to the remodeling of decidual arteries (55). The IFN-γ produced by dNK cells has also been shown to be involved in the cross-talk between NK and CD14+ cells in human decidua and the induction of Tregs (30). Furthermore, we revealed that high levels of IL-10, which also has a key role in suppressing TH17 cells, are secreted by normal dNK cells (50). The effects of these cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-1RA, may be synergistic in regulating TH17 cells and maintaining tolerance during pregnancy.

The phenotype of NK cells can be altered during episodes of severe inflammation. We selected recurrent spontaneous abortions as a model of a pathogenic state. Severe stress, viral infection, and autoimmune disorders may also cause abnormal pregnancy and inflammation (3, 5). We found that the percentages of dNK cells and the ratios of CD56brightCD27+ NK cells to TH17 cells decreased, the regulatory cytokines IFN-γ and IL-10 were impaired, and the inhibition of inflammation was lost in this pathological state. One possible explanation for this finding is that dNK cells have increased cytotoxicity toward inflammatory cells (54) but impaired regulatory capacity; another possibility is that after prolonged overactivation, NK cells may be immunodepleted and adopt an abnormal phenotype. It should be noted that during severe inflammation other cells in the decidua besides NK cells may also contribute to the loss of fetal tolerance via different mechanisms. Treg cells are known to mediate maternal tolerance through IL-10 (56), which decreased significantly in specimens from spontaneous abortion (57). Furthermore, uterine DC from mice with high abortion rates displayed decreased expression of IL-10 compared with that from mice with a low incidence of fetal rejection (58). Alternatively, activated macrophages or M2 macrophages also exert an immunosuppressive phenotype via the production of IL-10 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity (59). It would be interesting to determine how NK cells interact with such regulatory cell types during successful pregnancy in future studies.

We also present evidence for a direct relationship between TH17 cells and fetal loss. TH17 cells participate in inflammatory infiltration in patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions (60); this finding is important because TH17 cells represent a critical lineage of proinflammatory T-helper cells involved in autoimmune disease development (48, 49, 60, 61) and have been recognized as a barrier to the induction of tolerance in transplantation and pregnancy (17, 46). We also show that redundant TH17 cells directly cause fetal loss in vivo, which suggests that pregnancy pathologies may be affected by treatments targeting TH17 cells. We further show that increased levels of IL-6 and IL-1β induced an inflammatory microenvironment in the deciduas of patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions that may promote the expansion and recruitment of TH17 cells. These observations provide important clues for the pathogenesis of abnormal pregnancies and could be useful in further clinical research.

Our data suggest a model that during normal pregnancy dNK cells act as sentinel cells to control local inflammation, which is critical for maintaining tolerance at the fetal–maternal interface. However, this regulatory mechanism has limits, because NK cells can become altered by the inflammatory environment in that the non-NK cells in the decidua secrete high levels of IL-1β and IL-6, which promote the expansion and recruitment of TH17 cells. If inflammation is beyond the control of NK cells, tolerance is lost. These findings suggest a delicate role for dNK cells and the existence of a critical balance between dNK cells and other decidual cells and immune cells, such as DCs (62) and Treg cells (7, 21, 23, 56, 57, 63), in both physiological responses and pathological responses.

In summary, our data demonstrate that dNK cells can act as sentinel cells to prevent local inflammation and maintain successful pregnancy at the human maternal–fetal interface. We have shown that without NK cells, TH17 cells significantly contribute to decidual inflammation and abnormal pregnancies, and therefore NK cells seem to maintain fetal–maternal tolerance by suppressing the induction of TH17 cells. However, this role can be compromised in the presence of abnormal inflammation, which leads to the loss of TH17 cell control and ultimately to the loss of tolerance. These findings may have important clinical implications.

Materials and Methods

Human Samples and Cell Isolation.

Decidua samples from normal pregnancies (n = 285) were obtained from elective pregnancy terminations. Twenty-five deciduas from abnormal pregnancies were obtained from patients with recurrent spontaneous abortions (Table S1). Genetic or anatomical causes for abortions were excluded. The normal and abnormal samples were aged between 6 and 12 wk of gestation. Twenty term decidua samples were collected after normal delivery. All of the decidua samples were collected from the Anhui Provincial Hospital. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared from buffy coats obtained from healthy donors (Blood Center of Anhui Province) by centrifugation through Ficoll. Before surgery, informed consent was obtained from each patient. Ethical approvals were obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Science and Technology of China. Isolation of decidua samples is discussed in SI Materials and Methods.

Murine Models of Pregnancy.

Male and female C57BL/6 mice, male DBA/2, female EGFP C57BL/6 mice (8–10 wk old) were purchased from the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Science. Male and female CBA/J mice (8 wk old) were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. Nfil3−/− mice (without NK cells) were a generous gift from Tak Wah Mak (University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada). All animals were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. All of the experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the National Guidelines for Animal Use in Research (China), and permission was obtained from the ethics committee at the University of Science and Technology of China. Allogeneic CBA/J × DBA/2 mating combinations were established as follows: female CBA/J mice were mated in natural cycling with male DBA/2 mice. The allogeneic Nfil3−/− × BALB/c mating combinations were established as follows: female Nfil3−/− or Nfil3+/+ mice were mated in natural cycling with male BALB/c mice. Syngeneic CBA/J × CBA/J mating combinations were established in an identical manner. For the TH17 cell transfer assay, syngeneic C57BL/6 × C57BL/6 mating combinations were established. Detection of a vaginal plug was chosen to indicate day 0.5 of gestation. For the NK depletion assay, allogeneic CBA/J × DBA/2 mating combinations were established, and then the pregnant CBA/J mice were injected with 30 μL of anti–ASGM-1 (BD Biosciences) in 200 μL of PBS through the tail vein at gd 0.5, 4.5, and 8.5. Control animals were injected with 200 μL of PBS. Both groups were euthanized at 14.5 to examine the IL-17 expression and fetal resorption rate.

Induction of Human TH17 Cells and the Effect of NK Cells.

The CD4+ T cells were isolated from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy donors by magnetic bead depletion of CD19+, CD14+, CD56+, CD16+, CD36+, CD123+, CD8+, T-cell receptor-γ and T-cell receptor-δ-positive and glycophorin A-positive cells (CD4+T Cell Isolation Kit II; Miltenyi Biotec). The T cells were cultured for 6 d in 96-well round-bottom plates (Costar) at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in complete RPMI medium 1640. The cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (5 μg/mL; BD Biosciences) and anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL; BD Biosciences) antibodies. Human IL-23 (25 ng/mL; EBioscience), IL-1β (25 ng/mL; Peprotech), anti–IL-4(10 μg/mL; Peprotech), anti–IFN-γ (10 μg/mL; R&D Systems), and/or IFN-γ (100 ng/mL; Peprotech) were added at the start of the culture. The culture supernatants were collected after 6 d and analyzed by ELISA. To determine the effect of NK cells on TH17 expansion, the NK cells were isolated from the same human donor as the CD4+ T cells and were preactivated with IL-12 (100 U/mL), which was produced by our laboratory, for 12 h before they were added to the culture system at different ratios.

Decidual NK Cell Culturing.

Human dNK cells and non-NK mononuclear cells were cultured in the presence of IL-15 (10 ng/mL; Peprotech) for 60 h in 96-well flat-bottom plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in complete RPMI medium 1640. The supernatants from dNK cells and non-NK cells were collected and used for the ELISA analysis to detect IL-1β, IL-6, IL-1RA, IL-10, and IFN-γ. For the assays to determine the effects of dNK cells on the expansion of human TH17 cells, dNK cells and non-NK mononuclear cells were cultured under the following conditions: (i) IL-15 (10 ng/mL; Peprotech); (ii) IL-15 (10 ng/mL; Peprotech), IL-12 (100 U/mL, made by our laboratory), and IL-18 (50 ng/mL; Peprotech); and (iii) IL-15 (10 ng/mL; Peprotech) and low-dose PMA (10−7 M; Sigma). The cells were incubated for 60 h in 96-well flat-bottom plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in complete RPMI medium 1640. On the second day of TH17 cell culture, the supernatants from the dNK cells or non-NK mononuclear cells under different conditions were added into the TH17 cell expansion at a dose of 20 μL/well. Then, the supernatants from the TH17 cell cultures were collected after 6 d of culturing and analyzed by ELISA for IL-17.

Passive Transfer of TH17 Cells in Vivo.

Naïve CD4+T cells were isolated from the spleens of virgin female C57BL/6 mice by magnetic bead depletion of CD8a-, CD45R-, CD11b-, CD25-, CD49b-, TCRγ/δ-, and Ter-119-positive cells and then by the positive selection of CD62L+ cells (CD4+ CD62L+ T Cell Isolation Kit II; Miltenyi Biotec). In the control group, 1 × 106 naïve CD4+ T cells were resuspended in 200 μL of PBS and injected via the tail vein into pregnant C57BL/6 females on day 7.5 of gestation. In the TH17 cell transfer group, naïve CD4+ T cells were first incubated under conditions to induce polarization of the TH17 cells. The cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (5 μg/mL; BD Biosciences) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/mL; BD Biosciences) antibodies. Mouse TGF-β (2 ng/mL), IL-6 (20 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), anti-mouse–IFN-γ (10 μg/mL), and anti-mouse–IL-4 (10 μg/mL), all purchased from R&D Systems, were added to stimulate the differentiation of the TH17 cells for 6 d. The polarized cells were collected, and 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in 200 μL of PBS and then injected via the tail vein into each pregnant C57BL/6 female on day 7.5 of gestation. The recipient mice of both groups were killed on day 14.5 of gestation, and the uteri were examined for the number of healthy and resorbing embryos.

Quantitation of Embryo Resorption and Live Fetuses per Uterus.

On day 14.5 of gestation, the pregnant mice were killed and the uteri were examined for the resorption rate of the embryos. Resorbing embryos at this stage of gestation are subject to hemorrhage, ischemia, and necrosis and become smaller and darker than the larger, viable, pink, healthy embryos. The resorbing rate was calculated as follows: % resorbing rate = the number of resorbed embryos/the number of resorbed embryos and healthy embryos × 100. Live fetus per uterus was calculated as follows: Live fetus per uterus = the number of all fetuses per uterus − the number of resorbed embryos.

Statistical Analyses.

We used paired two-tailed t tests (difference between two groups) or unpaired two-tailed t tests to determine statistical significance (P < 0.05 was considered significantly different).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of China 973 Basic Science Project Grants 2013CB530506, 2009CB522403, and 2012CB519004 and Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81202367, 31021061, and 30730084.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Author Summary on page 818 (volume 110, number 3).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1206322110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sacks GP, Studena K, Sargent K, Redman CW. Normal pregnancy and preeclampsia both produce inflammatory changes in peripheral blood leukocytes akin to those of sepsis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trowsdale J, Betz AG. Mother’s little helpers: Mechanisms of maternal-fetal tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(3):241–246. doi: 10.1038/ni1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stillerman KP, Mattison DR, Giudice LC, Woodruff TJ. 2008. Environmental exposures and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A review of the science. Reprod Sci 15(7):631–650. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Sargent IL, Borzychowski AM, Redman CW. NK cells and human pregnancy—An inflammatory view. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(9):399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karimi K, Arck PC. Keepers of pregnancy in the turnstile of the environment. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(3):339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piccinni MP, et al. Defective production of both leukemia inhibitory factor and type 2 T-helper cytokines by decidual T cells in unexplained recurrent abortions. Nat Med. 1998;4(9):1020–1024. doi: 10.1038/2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mjösberg J, Berg G, Jenmalm MC, Ernerudh J. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and T helper 1, T helper 2, and T helper 17 cells in human early pregnancy decidua. Biol Reprod. 2010;82(4):698–705. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito S, et al. Quantitative analysis of peripheral blood Th0, Th1, Th2 and the Th1:Th2 cell ratio during normal human pregnancy and preeclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117(3):550–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin H, Mosmann TR, Guilbert L, Tuntipopipat S, Wegmann TG. Synthesis of T helper 2-type cytokines at the maternal-fetal interface. J Immunol. 1993;151(9):4562–4573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makrigiannakis A, et al. Corticotropin-releasing hormone promotes blastocyst implantation and early maternal tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(11):1018–1024. doi: 10.1038/ni719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu C, et al. 2000. A critical role for murine complement regulator crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science 287(5452):498–501.

- 12.Zhu XY, et al. Blockade of CD86 signaling facilitates a Th2 bias at the maternal-fetal interface and expands peripheral CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells to rescue abortion-prone fetuses. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(2):338–345. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guleria I, et al. A critical role for the programmed death ligand 1 in fetomaternal tolerance. J Exp Med. 2005;202(2):231–237. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poehlmann TG, et al. The possible role of the Jak/STAT pathway in lymphocytes at the fetomaternal interface. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;89:26–35. doi: 10.1159/000087907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayatollahi M, Geramizadeh B, Samsami A. Transforming growth factor beta-1 influence on fetal allografts during pregnancy. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(10):4603–4604. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Xiao X, Liu WT, Demirci G, Li XC. Inhibitory receptors of the immune system: Functions and therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6(6):407–414. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Addio F, et al. The link between the PDL1 costimulatory pathway and Th17 in fetomaternal tolerance. J Immunol. 2011;187(9):4530–4541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YJ, Park SJ, Broxmeyer HE. Phagocytosis, a potential mechanism for myeloid-derived suppressor cell regulation of CD8+ T cell function mediated through programmed cell death-1 and programmed cell death-1 ligand interaction. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2291–2301. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blois SM, et al. A pivotal role for galectin-1 in fetomaternal tolerance. Nat Med. 2007;13(12):1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nm1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munn DH, et al. 1998. Prevention of allogeneic fetal rejection by tryptophan catabolism. Science 281(5380):1191–1193.

- 21.Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, Sansom DM, Drayson MT. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112(1):38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tilburgs T, et al. Fetal-maternal HLA-C mismatch is associated with decidual T cell activation and induction of functional T regulatory cells. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;82(2):148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tilburgs T, et al. Evidence for a selective migration of fetus-specific CD4+CD25bright regulatory T cells from the peripheral blood to the decidua in human pregnancy. J Immunol. 2008;180(8):5737–5745. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn KH, Lacoursiere DY, Cui L, Bui J, Parast MM. The unique pathophysiology of early-onset severe preeclampsia: Role of decidual T regulatory cells. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;91(1-2):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karimi K, Blois SM, Arck PC. The upside of natural killers. Nat Med. 2008;14(11):1184–1185. doi: 10.1038/nm1108-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koopman LA, et al. Human decidual natural killer cells are a unique NK cell subset with immunomodulatory potential. J Exp Med. 2003;198(8):1201–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moffett A, Loke C. Immunology of placentation in eutherian mammals. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(8):584–594. doi: 10.1038/nri1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson H. Reproductive immunology: Immunity’s pregnant pause. Nature. 2002;420(6913):265–266. doi: 10.1038/420265a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moffett-King A. Natural killer cells and pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(9):656–663. doi: 10.1038/nri886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vacca P, Moretta L, Moretta A, Mingari MC. Origin, phenotype and function of human natural killer cells in pregnancy. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(11):517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabiasco J, et al. 2006. Human decidual NK cells: Unique phenotype and functional properties–A review. Placenta 27(Suppl A):S34–39.

- 32.Nakashima A, Shima T, Inada K, Ito M, Saito S. The balance of the immune system between T cells and NK cells in miscarriage. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67(4):304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2012.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanna J, et al. Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat Med. 2006;12(9):1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/nm1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalkunte SS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor C facilitates immune tolerance and endovascular activity of human uterine NK cells at the maternal-fetal interface. J Immunol. 2009;182(7):4085–4092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mignini F, Traini E, Tomassoni D, Vitali M, Streccioni V. Leucocyte subset redistribution in a human model of physical stress. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2008;30(8):720–731. doi: 10.1080/07420520802572333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans DL, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and substance P antagonist enhancement of natural killer cell innate immunity in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(9):899–905. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azpiroz A, De Miguel Z, Fano E, Vegas O. Relations between different coping strategies for social stress, tumor development and neuroendocrine and immune activity in male mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(5):690–698. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vossen MT, et al. CD27 defines phenotypically and functionally different human NK cell subsets. J Immunol. 2008;180(6):3739–3745. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fu B, et al. CD11b and CD27 reflect distinct population and functional specialization in human natural killer cells. Immunology. 2011;133(3):350–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiossone L, et al. Maturation of mouse NK cells is a 4-stage developmental program. Blood. 2009;113(22):5488–5496. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-187179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Bouteiller P, Piccinni MP. Human NK cells in pregnant uterus: why there? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59(5):401–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McQueen KL, Parham P. Variable receptors controlling activation and inhibition of NK cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14(5):615–621. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manaster I, et al. Endometrial NK cells are special immature cells that await pregnancy. J Immunol. 2008;181(3):1869–1876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kopcow HD, et al. Human decidual NK cells form immature activating synapses and are not cytotoxic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15563–15568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507835102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mingari MC, Ponte M, Cantoni C, Moretta L. Natural killer cells in pregnancy: How do they avoid attacking fetal tissues? Immunologist. 1999;7(4):107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan X, et al. A novel role of CD4 Th17 cells in mediating cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy. J Exp Med. 2008;205(13):3133–3144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang WJ, et al. The deregulation of regulatory T cells on interleukin-17-producing T helper cells in patients with unexplained early recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(10):2591–2596. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park H, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(11):1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huber S, et al. Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3⁻ and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34(4):554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou R, Wei H, Tian Z. NK3-like NK cells are involved in protective effect of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid on type 1 diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2007;178(4):2141–2147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vivier E, Spits H, Cupedo T. Interleukin-22-producing innate immune cells: New players in mucosal immunity and tissue repair? Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(4):229–234. doi: 10.1038/nri2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bilinski MJ, et al. Uterine NK cells in murine pregnancy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16(2):218–226. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy SP, Fast LD, Hanna NN, Sharma S. Uterine NK cells mediate inflammation-induced fetal demise in IL-10-null mice. J Immunol. 2005;175(6):4084–4090. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashkar AA, Di Santo JP, Croy BA. Interferon gamma contributes to initiation of uterine vascular modification, decidual integrity, and uterine natural killer cell maturation during normal murine pregnancy. J Exp Med. 2000;192(2):259–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aluvihare VR, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(3):266–271. doi: 10.1038/ni1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sasaki Y, et al. Decidual and peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in early pregnancy subjects and spontaneous abortion cases. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10(5):347–353. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blois S, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1/LFA-1 cross talk is a proximate mediator capable of disrupting immune integration and tolerance mechanism at the feto-maternal interface in murine pregnancies. J Immunol. 2005;174(4):1820–1829. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagamatsu T, Schust DJ. The immunomodulatory roles of macrophages at the maternal-fetal interface. Reprod Sci. 2010;17(3):209–218. doi: 10.1177/1933719109349962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang WJ, et al. Increased prevalence of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in peripheral blood and decidua in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion patients. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;84(2):164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saito S, Nakashima A, Shima T, Ito M. Th1/Th2/Th17 and regulatory T-cell paradigm in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63(6):601–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Degli-Esposti MA, Smyth MJ. Close encounters of different kinds: dendritic cells and NK cells take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(2):112–124. doi: 10.1038/nri1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kallikourdis M, Andersen KG, Welch KA, Betz AG. Alloantigen-enhanced accumulation of CCR5+ ‘effector’ regulatory T cells in the gravid uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(2):594–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604268104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]