Abstract

The pH 6 antigen (Psa) of Yersinia pestis consists of fimbriae that bind to two receptors: β1-linked galactosyl residues in glycosphingolipids and the phosphocholine group in phospholipids. Despite the ubiquitous presence of either moiety on the surface of many mammalian cells, Y. pestis appears to prefer interacting with certain types of human cells, such as macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells of the lung. The molecular mechanism of this apparent selectivity is not clear. Site-directed mutagenesis of the consensus choline-binding motif in the sequence of PsaA, the subunit of the Psa fimbrial homopolymer, identified residues that abolish galactosylceramide binding, phosphatidylcholine binding, or both. The crystal structure of PsaA in complex with both galactose and phosphocholine reveals separate receptor binding sites that share a common structural motif, thus suggesting a potential interaction between the two sites. Mutagenesis of this shared structural motif identified Tyr126, which is part of the choline-binding consensus sequence but is found in direct contact with the galactose in the structure of PsaA, important for both receptor binding. Thus, this structure depicts a fimbrial subunit that forms a polymeric adhesin with a unique arrangement of dual receptor binding sites. These findings move the field forward by providing insights into unique types of multiple receptor–ligand interactions and should steer research into the synthesis of dual receptor inhibitor molecules to slow down the rapid progression of plague.

Keywords: adhesin–receptor complex, adhesion, ligand binding, sugar binding, phosphocholine binding

Owing to a well-documented history of deadly pandemics that nearly disrupted human civilization over the last 1,500 years, plague is often mistaken as a disease of antiquity. Contrary to this view, plague is still a major public health concern with widespread epidemics and isolated cases occurring in many countries of the world (1). Yersinia pestis is the etiological agent of plague and thus classified as a category A bioterrorism agent. Several major virulence factors of Y. pestis are harbored on a 70-kb plasmid, pCD1, which encodes the Yersinia type III secretion system (T3SS) and the Yop effector proteins (Yops) (2). Adhesin-mediated binding of Y. pestis to host cells facilitates the insertion of the T3SS apparatus on to the host cells and subsequent Yops injection, which is critical to plague pathogenesis. The pH 6 antigen (Psa) of Y. pestis has been shown to be a key adhesin that facilitate Yops delivery, besides other adhesins such as Ail and Pla (3).

The Psa of Y. pestis is a surface homopolymer made of the structural subunit PsaA that is assembled via the chaperone-usher pathway (4). Psa belongs to the class of FGL (long F1-G1 loop) fimbriae and is a bacterial homopolymeric adhesin or polyadhesin (5). By contrast, the Afa/Dr and Saf polyadhesins of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica, respectively, all consist of a major multimeric adhesin and an additional tip-located invasin (4). In addition to Psa, the surface of Y. pestis also displays a homopolymeric structure known as the F1 capsule that is grouped with the FGL surface proteins and is assembled by the chaperone–usher pathway (4). However, the F1 polymer does not act as a polyadhesin but effectively inhibits phagocytosis (6, 7).

Psa is expressed under the conditions of low pH (5.0–6.7) and temperatures of 35–41 °C (8). Psa has been shown to agglutinate red blood cells (9) and, like F1, to inhibit phagocytosis by macrophages (10). A number of studies have also highlighted that Psa is expressed in vivo in infected tissues (11) and plays a key role in virulence of Y. pestis (12, 13). Recent studies have shown that the Psa antigen induces a robust immune response and induces significant albeit incomplete protection in a murine model of pneumonic plague (11). Psa has also been shown to mediate binding to cells, including human respiratory tract epithelial cells (7, 9), as well as to pulmonary surfactant (5), which coats the alveolar surface of lungs. Two major receptors that interact with Psa have been identified: β1-linked galactosyl residues in glycosphingolipids (14) and phosphatidylcholine (PC) present on alveolar epithelial cells (5).

Interestingly, many of the FGL-assembled structures are either not detectable by negative-stain electron microscopy (thus designated afimbrial or nonfimbrial adhesins) or appear as featureless electron-dense masses around the bacteria (4, 7). Only in some studies were a few of these structures visualized as bacterial extensions (15, 16) or as linear thin fimbriae (of ∼2–4 nm wide) that are mostly clumped together in small bundles (17, 18). However, a structural view at atomic resolution on the subunit PsaA, its assembly into a polyadhesin, and how the two receptors interact with the Psa fimbriae were absent. In fact, the lack of structural information on Psa and its low sequence similarity to known structures of FGL family members further aggravate the problem in defining the role of these two receptors in the infection process by Y. pestis. By using structural techniques, site-directed mutagenesis, and ligand binding assays, we identified amino acid residues that are involved in Psa binding to the two receptors. We mapped these residues to the structure of PsaA determined by X-ray crystallography in the presence of receptors. The role of these residues in the context of Psa binding to human cells is further demonstrated.

Results

Psa Shares a Consensus Motif with a Family of Bacterial Choline-Binding Proteins.

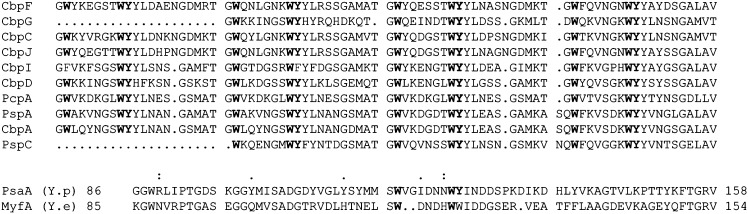

Previous studies carried out in our laboratory have identified that Psa binds in a dose–response fashion to PC, which is inhibited by choline or phosphocholine (PCho), indicating that Psa interacts with the choline head group in PC (5). PC is ubiquitously present as a major component of most eukaryotic membrane, whereas it is rarely present in prokaryotes (19). Choline, on the other hand, is encountered in the cell wall as a component of teichoic and lipoteichoic acids of a number of bacteria including many species of streptococci (20). A family of bacterial proteins, broadly called choline-binding proteins (CBPs), use choline binding as a strategy to get noncovalently anchored to the choline-containing gram-positive cell wall after being exported to the bacterial surface. Each choline-binding module consists of multiple tandem repeats of choline-binding motif made of 20-amino acid residues with a consensus sequence of W-6X-WY (21). Sequence comparison and alignment of PsaA with choline-binding repeats of CBP of pneumococci (Fig. 1) revealed that PsaA harbors a single copy of the same motif. Because each Psa fimbria is a bacterial surface organelle consisting of hundreds of polymerized PsaA subunits (17), it is conceivable that Psa could interact with choline molecules in a manner not too different from bacterial CBPs.

Fig. 1.

Sequence motif of dscPsaA. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of PsaA of Y. pestis and MyfA of Y. enterocolitica with those of the choline-binding motifs of Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 CBPs (21). Highly conserved residues of the motif are shown in bold. PCho and β1-linked galactose-binding residues of Psa are indicated by a period and a colon above the PsaA sequence, respectively.

To demonstrate experimentally that this choline-binding motif in PsaA is indeed involved in binding PC, we substituted key amino acids in and around the consensus W-6X-WY sequence of PsaA with alanine or other amino acids in some cases. Substituted variants of PsaA were expressed in the nonfimbriated E. coli SE5000 strain. The bacteria were then checked for total expression of PsaA, for fimbriation by heat extraction of exported and surface assembled Psa, and by agglutination with anti-Psa serum (Table 1). The bacteria were also evaluated for receptor binding by agglutination with liposomes containing PC or galactosylcerebroside (GC; Table 1). Substitution of the highly conserved tryptophan residue W118 or W125 in the putative choline-binding motif with alanine reduced PsaA detection and interfered with Psa fimbriation, suggesting protein misfolding that leads to cellular degradation and/or defective fimbrial biogenesis. Even though substitution with another hydrophobic residue (isoleucine) gave a comparable result, change to another aromatic residue (phenylalanine) restored fimbrial expression and binding to both receptors, suggesting that aromatic residues in these positions are essential not only for structural stability of PsaA and subsequent fimbrial biogenesis but also for receptor binding. Alanine substitutions of four residues between the two conserved tryptophan residues (V119, G120, D122, and N123) resulted in no detectable difference from the WT phenotype. By contrast, replacement of isoleucine I121 with alanine resulted in defective binding to PC. Surprisingly, two other substitutions (N124A and Y126A) affected GC, but not PC, recognition. The latter result indicated that the canonical choline-binding motif of PsaA includes residues that are exclusively required for recognition of the second receptor, GC. This finding was unanticipated, because previous biochemical studies suggested independent binding pockets for the two receptors (5). As expected, a mutant with double mutations I121A and N124A lost both binding properties. Mutants D122A and Y126A expressed Psa antigen on the bacterial surface that recognized at least one receptor, but the isolation of mutant Psa by heat extraction was less efficient or not possible, suggesting that the mutated proteins created new and stronger interactions with an anchored bacterial surface component.

Table 1.

Phenotypes and characterization of engineered psaA mutants*

| PsaA mutation | PsaA expression† | Psa on bacteria |

Binding ¶ |

HA titer|| | Suggested roles by structure/function analyses | ||

| Isolation‡ | Antigen§ | PC | GC | ||||

| WT** | + | + | + | + | + | 128 | |

| ΔpsaA | − | − | − | − | − | <1 | |

| R89A†† | + | + | + | + | − | 128 | Gal binding (2.9 Å)‡‡ |

| Y100A | + | + | + | − | + | <1 | PC binding |

| L111A | − | − | − | − | − | ND | Structural |

| Y112A | + | + | + | − | + | 8 | PC binding |

| W118A | +/− | − | − | − | − | ND | PC binding, structural |

| W118I | +/− | − | − | − | − | ND | PC binding, structural |

| I121A | + | + | + | − | + | 32 | Structural |

| D122A | + | — | + | + | + | 128 | In contact with Gal (2.5 Å)‡‡ |

| N124A | + | + | + | + | − | 128 | Gal binding |

| W125A | − | − | − | − | − | ND | PC binding, structural |

| W125I | − | − | − | − | − | ND | PC binding, structural |

| Y126A | + | +/− | + | + | − | <1 | Gal binding, two sites communication |

| N128A | + | + | + | + | + | ND | In contact with Gal (2.7 Å)‡‡ |

| L139A | − | − | − | − | − | ND | Structural |

| Y161A | ND | ND | + | + | + | ND | In contact with Gal (4.2 Å)‡‡ |

| F163A | ND | ND | + | + | + | ND | None |

| I121A,N124A§§ | + | + | + | − | − | <1 | |

| R89A,N124A | + | + | + | + | − | 128 | |

ND, not determined.

*E. coli SE5000 expressing the Y. pestis psaABC from a constitutive tetA promoter.

†PsaA expression in whole cell lysates (Western blot) using an antiserum to Psa (7).

‡Fimbriae were isolated from bacterial surfaces by heat extraction (7).

§Bacterial surface-exposed Psa antigen was detected bacterial seroagglutination (7).

¶Bacterial binding to liposomes carrying PC or GC (5).

||Hemagglutination by E. coli SE 5000 expressing WT and mutant variants of Psa (9).

**WT and mutants with the same phenotypes: Y100F, Y112F, M115A, M116A, W118F, V119A, G120A, N123A, and W125F.

††Arginine was replaced with an alanine at position 89 of PsaA.

‡‡Contact distance in Å.

§§Mutant with same phenotypes: ΔV119-N124::DNDH (V119-N124 substituted with the corresponding sequence of MyfA [DNDH]).

Crystal Structure of the in cis Donor-Strand Complemented Fimbrial Subunit PsaA in Complex with Galactose.

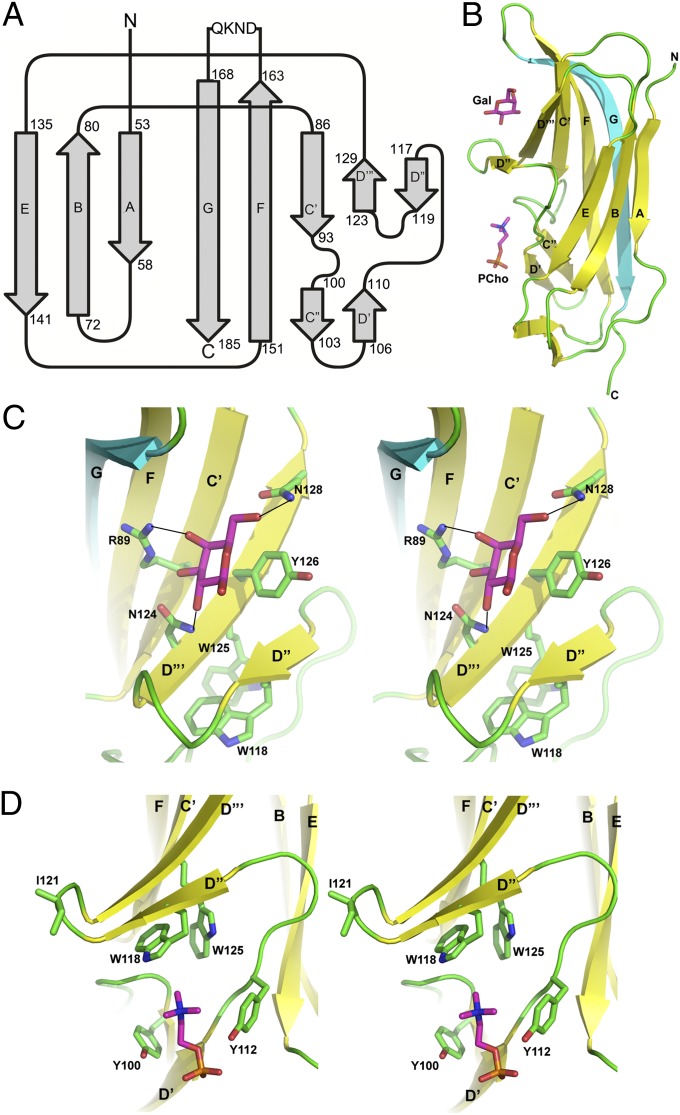

The crystal structure of donor-strand complemented fimbrial subunit PsaA (dscPsaA) in complex with galactose was determined and refined (Table S1). Similar to subunit structures of other fimbriae that are assembled by the usher–chaperone pathway (4) the structure of dscPsaA has a typical Ig fold of a seven-stranded β-sandwich (Fig. 2 A and B). During fimbria assembly, the last β-strand or G strand is provided by the N-terminal donor strand of an adjacent subunit in a mechanism dubbed the donor-strand complementation (DSC) (4). In dscPsaA, DSC is achieved by self-complementation through the C-terminally in cis–engineered donor strand (Fig. S1). Prominent features perhaps unique to PsaA are the structural motifs between β-strands C′ and E including β-strands C″, D′, D″, and D‴, as well as associated loops between the β-strands, which deviates significantly from other major fimbrial subunits with known structures (Fig. 2 A and B).

Fig. 2.

Crystal structures of dscPsaA in complex with receptors. (A) A topological diagram of dscPsaA structure. (B) Ribbon representation of the structure of the ternary complex of dscPsaA with bound galactose and phosphocholine. All β-strands are shown in yellow except for the donor strand, which is shown in cyan, and labeled. All loops connecting pairs of β-strands are shown in green coils. Bound receptor molecules are shown as stick models with carbon atoms colored in magenta, nitrogen in blue, phosphorus in yellow, and oxygen in red. (C) Stereoscopic pair showing details of the galactose-binding niche. The bound galactose molecule and residues important for its binding are given as stick models and labeled. Potential hydrogen bonds are drawn as black lines. (D) Stereoscopic pair showing details of the phosphocholine-binding pocket. Phosphocholine and residues involved in its binding are shown as stick models.

Calculation of the difference Fourier revealed a prominent feature that was unambiguously identified as the bound galactose molecule (Fig. 2C). In all of the structures reported here, the galactose moiety is found identically residing in a shallow surface niche bound by residues from β-strands C′, D″, and D‴ and associated loops (Figs. 2C and S2). The structure of the complex reveals that the galactose-binding niche bears similarity to that of type C carbohydrate-binding module (CBM), which is classified as CBMs binding optimally to mono, di-, or trisaccharides (22). Like all CBMs, the side chain of the aromatic residue Y126 from the strand D‴ plays a critical role as a hydrophobic platform to “mirror” the pyranose ring of galactose through a carbohydrate–π interaction (Fig. 2C), which is commonly observed in structures of carbohydrate–CBM complexes (22, 23). Despite a low IC50 (∼40 mM) of galactose toward PsaA, the binding site was shown to be specific for the galactose moiety (5). The bound galactose is surrounded by side chains from residues R89, N124, and N128, likely forming hydrogen bonds to the sugar (Fig. 2C). In particular, residue N128 provides its amide group to forms a hydrogen bond (2.7 Å) with the hydroxyl oxygen of the galactose at C6 position and presumably determines the binding preference for hexoses over pentoses in this pocket. Discrimination against other hexoses such as glucose and mannose is provided by R89 and N124, whose side chains interact with hydroxyl groups from carbon atoms C2, C3, and C4 of the bound galactose (Fig. 2C).

Interestingly, the difference Fourier map also revealed a large piece of electron density located in a hydrophobic surface depression near the sugar binding niche, which is delimited at one end by the twin tryptophan residues of the consensus choline-binding motif W-6X-WY. This density can be best fitted with the protease inhibitor 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF) that was used during protein purification (Fig. S3). Unlike PCho that has a quaternary amine group, the AEBSF possesses a terminal amino group that is pointing toward the twin tryptophan residues. In the absence of the protease inhibitor, the purified dscPsaA crystallized into a different crystal form with the symmetry of space group P65 (Table S1). Unexpectedly, the AEBSF site remained occupied by the imidazole ring of a histidine residue from the hexahistidine tag of a neighboring molecule.

We also determined the structure of dscPsaA cocrystallized with the disaccharide lactose (Table S1). Not surprisingly, the galactosyl moiety of the lactose was found binding to the dscPsaA in exactly the same manner as it was found in the galactose bound structures, whereas the glucose moiety stayed outside the binding niche, making no apparent contacts with the protein (Fig. S2). This structure further confirmed the specificity of PsaA toward binding of the galactosyl moiety. More importantly, this result suggests that PsaA most probably only recognize the galactosyl moiety located at the tip of a polysaccharide.

Crystal Structure of the Ternary Complex of dscPsaA, Galactose, and Phosphocholine.

The presence of the AEBSF binding site nearby the carbohydrate-binding niche inspired us to crystallize the dscPsaA, galactose, and PCho ternary complex. The complex crystal, obtained in the presence of 10 mM PCho, diffracted X-rays to 2.3 Å. As expected, the difference Fourier map gave excellent density for the bound galactose. Most importantly, the difference map also revealed a piece of extra density with a shape resembling that of PCho in the same site previously occupied by AEBSF.

The PCho site and the galactose-binding niche are separated by the D″-D‴ hairpin. In other words, the D″-D‴ hairpin contributes to both galactose and PCho binding (Figs. 2B and 3A). Compared with the galactose-binding niche, the PCho binding site is considerably more hydrophobic, and it is surrounded, in addition to the twin tryptophan residues W118 and W125, by predominately hydrophobic residues such as G99, Y100, Y112, and G110 (Fig. 2D). Similar to the binding of various cholines to their respective receptors, both natural and synthetic (24, 25), the binding of PCho to PsaA is mediated by the “aromatic guidance” mechanism, in which the positively charged quaternary ammonium group from PCho is trapped by an aromatic ring system made of side chains from residues W118, W125, and Y112 via the characteristic cation–π interaction (Fig. 2D). Additionally, one of the oxygen atoms of the phosphate group is likely hydrogen bonded to the amide nitrogen of G110 (3 Å), providing additional interaction. Thus, the cation–π interaction, although relatively weak, forms the structural basis for the specificity of Psa toward PC (26, 27).

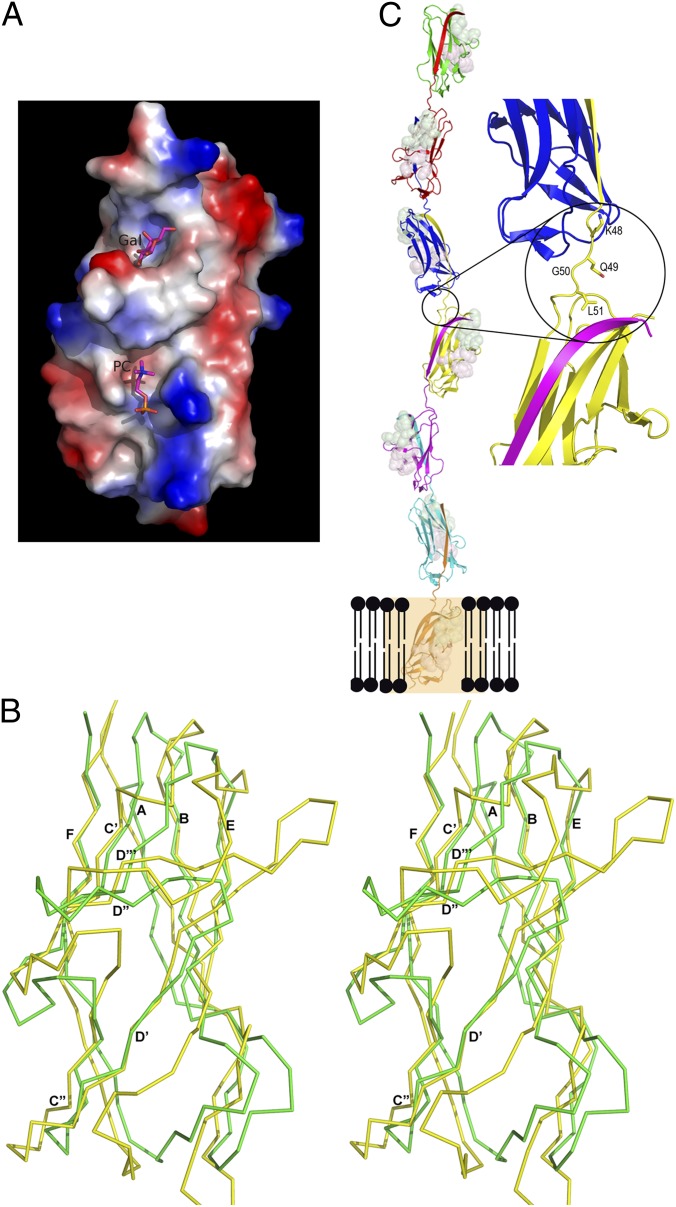

Fig. 3.

Structural analysis of PsaA, its alignment with Cfa1 pilin, and functional implications. (A) Electrostatic potential surface of dscPsaA. The red and blue surfaces represent negative and positive potentials, respectively. White surface indicates a hydrophobic surface. Bound receptors are shown as stick models with the same color codes as in Fig. 2. (B) Structural alignment of dscPsaA and Caf1 pilin in the FGL family, showing as Cα tracing in green and yellow, respectively. (C) Model of Psa polyadhesin based on the structure of the F1 fimbriae (32). Seven subunits are shown, in which residues interacting with galactose are drawn as sphere models in light green and those interacting with PCho are colored in pink. Magnified portion shows the linkage between two neighboring subunits.

Interactions Between Galactose and Phosphocholine Binding Sites Revealed by Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

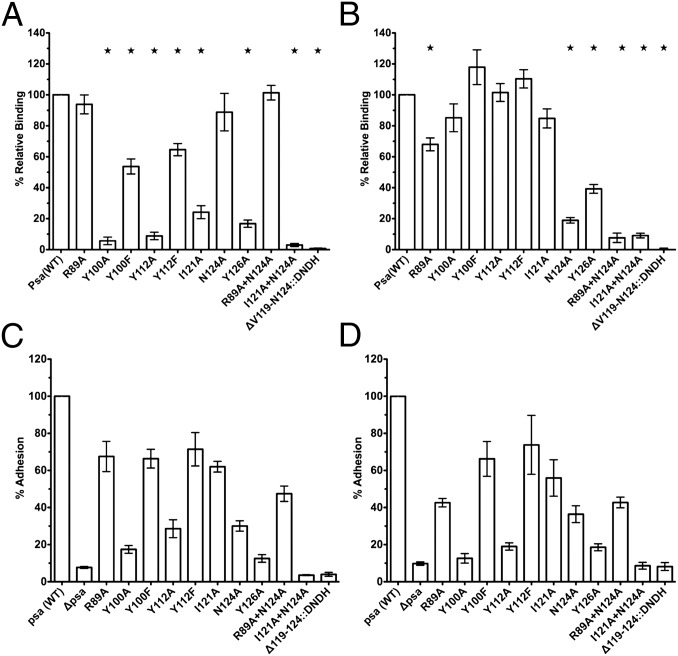

The consensus choline-binding motif in PsaA (Fig. 1) includes a conserved aromatic residue Y126, which, in the structure of CBP from bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (PDB: 2XBM), contributes to the choline-binding site of the preceding motif. The crystal structure of dscPsaA reveals instead that Y126 is an integral constituent of the galactose-binding site, providing direct contact with the bound galactose via the pyranose ring–π interaction (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, E. coli expressing mutant Y126A Psa fimbriae lost binding not only to GC, but also to PC immobilized on a solid surface (Table 1; Fig. 4 A and B). This mutation also abrogated hemagglutination activity of Psa fimbriae (Table 1). More importantly, the same observation extends to binding of the Y126A mutant to both lung epithelial–derived A549 and murine macrophage line RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 4 C and D). Thus, there exists structural and biochemical evidence to suggest a functional linkage between the sugar and choline binding sites in PsaA. Consistent with this view, residues R89 and N124 also play a role in GC binding as mutations of these two residues reduce binding of GC to varying degrees (Fig. 4 A and B). Expectedly, the reduction of galactose binding in these mutants also affected their binding to PC, which was indeed observed in the binding assay to A549 and RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 4 C and D).

Fig. 4.

Changes in binding properties of WT and variant Psa. Binding of WT and substituted variants of Psa to PC (A) or GC (B) was evaluated by ELISA. The data are expressed as mean percent adhesion relative to the WT ± SE of three values and represent one of three reproducible experiments. *P < 0.05. Adhesion of E. coli SE 5000 expressing WT and substituted variants of Psa to A549 cells (C) or RAW 264.7 cells (D). Adhesion assays were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Adherence percentages were calculated as the numbers of cell-associated bacteria divided by the total numbers of inoculated bacteria × 100 and were expressed as percent adhesion relative to the WT value (mean ± SE of three paired values that represent one of three reproducible experiments). All of the shown strains expressing mutated Psa bound significantly less well to both cell lines than the bacteria expressing WT Psa (P < 0.05).

Because the choline-binding motif is a large part of the D″-D‴ hairpin, it is conceivable that mutations introduced to residues in this hairpin would affect binding of either receptor. This effect was precisely observed for residue I121 that is located at the very tip of the D″-D‴ hairpin and has no contacts with either bound Gal or PCho, yet its mutation led to the loss of binding to PC (Fig. 4A). The variant with double mutations of I121A and N124A resulted in the loss of binding to both GC and PC, further supporting the importance of D″-D‴ hairpin for receptor binding.

Discussion

Phospholipid Binding in Psa.

The Psa polyadhesin has two known cellular receptors; both are abundantly present in mammalian cell membranes (5). Variable binding properties for different cells are most likely modulated by relative receptor densities, length and hydroxylation of the fatty acid chains, and types and densities of neighboring membrane lipids and glycoproteins (28). The importance of an intact choline-binding motif to preserve PsaA’s choline-binding ability and specificity was demonstrated by our mutagenesis experiment in MyfA, a subunit equivalent to PsaA for Yersinia enterocolitica, which features an incomplete choline-binding motif (W-4X-WY) (Fig. 1). Substituting the choline-binding motif in PsaA with the corresponding shorter one of MyfA abrogated binding to both receptors (Table 1).

The crystal structure of PsaA readily explains the phenotypes of mutations introduced to the aromatic residues W118, W125, Y112, and Y100 in the choline-binding motif (Table 1). Even though these residues participate in the formation of a hydrophobic pocket for binding to PC as seen in crystal structures, only the tyrosine residues (Y100 and Y112, along with Y126) but not the two tryptophan residues could be substituted with alanine without affecting PsaA fimbriation, because the latter two residues also confer a structural role to the stability of the subunit. This point is further demonstrated by substituting the two tryptophan residues with phenylalanine, which affect neither fimbriation nor binding (Table 1). Moreover, the fact that any alanine substitutions to those residues essentially abolished PC binding, whereas phenylalanine substitutions preserved significant binding ability, confirmed the importance of the aromatic guidance mechanism for PCho binding (Table 1). Quantitative measurements showed that substitutions of Y100 or Y112 with a phenylalanine preserved nearly 60–70% of PC binding (Fig. 4A). Thus, binding was maintained despite the absence of interactions between the phosphate group of PC and the hydroxyl groups of the two tyrosine residues, in agreement with the prior observation that only the choline group is important for binding (5).

E. coli expressing any of the Psa variants with a substitution in PsaA that impaired binding to PC, GC, or both were evaluated for their agglutinating properties with sheep red blood cells (RBCs). Noticeably, only the bacteria with Psa variants that were impaired in binding to PC were deficient in hemagglutinating activity (Table 1). Bacteria expressing the Psa variant with the corresponding shorter MyfA (W-4X-WY) substitution for the choline-binding motif did not agglutinate RBCs, consistent with the nonhemagglutinating phenotype described for the Myf fimbriae (15). Taken together, our data indicated that the hemagglutinating property of Psa is due to its specificity for cholines on RBCs.

Binding of β1-Galactosyl Moiety of Glycosphingolipid.

Earlier studies showed that the Psa–PC and Psa–GC interactions were independent of each other (5). Galactose and lactose interfered only with the Psa–GC interaction but not with the Psa–PC interaction, whereas monomeric or polymeric PCho disturbed only Psa binding to PC but not to GC. These results indicated that Psa fimbriae use separate domains for binding of its two receptors, which is confirmed by our crystal structure of the ternary complex of dscPsaA, galactose, and PCho. More significantly, the crystal structure found that the two receptor-binding sites share a common structural motif, the D″-D‴ hairpin, which contains the choline-binding motif W-6X-WY. Moreover, residue Y126 of the motif is in fact part of the galactose-binding niche in direct contact with the bound sugar. The juxtaposing location of the two binding pockets is consistent with mutagenesis results, which identified residues required mainly for either one or both receptor–PsaA interactions.

The close proximity of the two receptor-binding sites suggests likely interaction between the two, which has thus far received limited experimental support. Supporting evidence came from the Y126A mutation that leads to the loss of binding not only to GC but also to PC. The affinity of the galactosyl moiety as indicated by IC50 (∼40 mM) is considerably lower than that for choline (∼4 mM), suggesting a secondary role of the sugar binding in the attachment of host cells. Moreover, mutations introduced to residues (N124A and R89A) that interfere with sugar binding, but not the PC binding (Fig. 4 A and B), demonstrated significantly reduced efficiency to binding of macrophage and lung-derived cells (Fig. 4 C and D). However, no significant conformational change could be observed to the choline-binding site in the presence or absence of the occupant in the choline-binding site. The presence of galactose did not produce a synergistic effect on the affinity of PC binding to dscPsaA, as measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Fig. S4). Nevertheless, it remains possible that undetected weak interactions between the two binding sites in a subunit are amplified in the polymeric fimbrial structure and that Psa binding to GC primes its binding to PC.

Structural and Functional Role of the D″-D‴ Hairpin Insertion.

A unique feature of PsaA is its D″-D‴ hairpin that contains the choline-binding motif; it is located roughly midway between the two receptor binding sites, serving as a barrier segregating the two sites. This feature provides a structural basis for the existence of two biochemically observed, independent receptor-binding domains. The crystal structure of dscPsaA bears no similarity to any choline-binding proteins with known structures. Even the highly conserved choline-binding motif is by no means conserved with respect to the position and orientation of side chains of conserved residues. Namely, superposition of bound choline moieties between dscPsaA and other choline binding proteins does not bring conserved tryptophan and tyrosine residues into alignment, suggesting a very distant evolutionary relationship between Yersinia PsaA and the streptococcal CBPs.

Members of FGL fimbriae such as Psa, F1, Saf, and Afa/Dr display either amorphous, capsule-like morphologies, or flexible polyadhesins, some consisting of a polymerized single type of adhesive subunits (4). Although sharing similar overall structures, the subunits from these fimbriae present functionally distinct characteristics. The main difference seems to be in the highly variable D strands of the adhesin subunits, which are consensus receptor-binding sites in poly-adhesion fimbriae (4, 29). The D″-D‴ hairpin motif presents a feature unique to Psa fimbriae, a longer D″-D″′ hairpin that can be seen clearly by aligning PsaA with other known structures among the FGL family fimbriae such as Caf1 and DraE. Caf1 and DraE are more similar to each other than to PsaA; PsaA has a longer D″-D‴ hairpin, whereas Caf1 and DraE each has a longer C″-D′ loop (Fig. 3B; Fig. S5).

Model for Polyadhesin Binding to Host Cells.

Based on the dscPsaA structure of the ternary complex, a putative model for Psa fimbriae can be built (Fig. 3C). Unlike rod-shaped fimbriae such as CFA/I, where the connection between the two major subunits CfaB is a single proline residue (30), the intersubunit connection for a Psa fimbria has four residues (48-KGQL-51) that makes it very flexible and allows simultaneous binding by a number of subunits to available receptors, as previously described with polymeric inhibitors (5). Additive fimbrial binding to the two cell receptors (5) suggested simultaneous binding to both receptors, consistent with the subunit crystal structure with its two receptors. That different fimbrial filaments bind different receptors is unlikely, because of the 10-fold higher affinity of Psa for PC than for GC (5).

The two binding sites of Psa share a common character of very weak binding to their respective receptors, implying a selective mechanism when subunits are polymerized. Conceivably, the binding avidity depends on the presence and distribution of both receptors on cell membranes and on the average size of the Psa fimbriae, as well as the number of fimbriae per cell for bacterial binding. Psa might first encounter and bind to galactose residues that decorate glycolipid or glycoprotein on cell membranes from a greater distance than PCho before binding with greater avidity to PC. Whether shear forces enhance the binding of Psa, as described for some other fimbriae, remains to be determined (4).

Materials and Methods

Psa-Expressing Bacteria and psaA Mutagenesis.

Recombinant Psa was expressed on the nonfimbriated E. coli host strain SE5000 (MC4100 recA56 Fim–) from plasmid pGS1, and psaA site-directed mutants were constructed by fusion PCR (Table S2) as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Isolation of Psa Fimbriae: Binding and Agglutination Assays.

The isolation of Psa fimbriae, binding, and agglutination assays were described previously (5, 7, 9), with slight modifications given as part of SI Materials and Methods.

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of in cis dscPsaA for Structure Analysis.

An in cis donor-strand complemented monomeric psaA (dscpsaA) construct with a His-tag was created by PCR (Table S2) using pGS1 as a template to create pET-22b::dsc18psaA(his)6 for the expression and purification of a stable dscPsaA protein, using a previously described strategy (31), as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Crystallization, Structure Determination, Refinement for dscPsaA Structures, and ITC.

Details of crystallization and ITC procedures are given in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline staff of the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) at Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory for assistance in data collection. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant AI076695, a University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation grant, and Research Initiative Funds from the University of Pennsylvania Veterinary Center for Infectious Disease (to D.M.S.); and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and by a grant from the Trans NIH/Food and Drug Administration Intramural Biodefense Program (to D.X.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 4F8L (AEBSF adduct of dscPsaA in complex with galactose); 4F8N (dscPsaA in complex with galactose and phosphocholine); 4F8O (AEBSF adduct of dscPsaA in complex with lactose); and 4F8P (dscPsaA in complex with galactose)].

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1212431110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Stenseth NC, et al. Plague: Past, present, and future. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viboud GI, Bliska JB. Yersinia outer proteins: Role in modulation of host cell signaling responses and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:69–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felek S, Tsang TM, Krukonis ES. Three Yersinia pestis adhesins facilitate Yop delivery to eukaryotic cells and contribute to plague virulence. Infect Immun. 2010;78(10):4134–4150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00167-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zavialov A, Zav’yalova G, Korpela T, Zav’yalov V. FGL chaperone-assembled fimbrial polyadhesins: anti-immune armament of Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007;31(4):478–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galván EM, Chen H, Schifferli DM. The Psa fimbriae of Yersinia pestis interact with phosphatidylcholine on alveolar epithelial cells and pulmonary surfactant. Infect Immun. 2007;75(3):1272–1279. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01153-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Y, Rosqvist R, Forsberg A. Role of fraction 1 antigen of Yersinia pestis in inhibition of phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 2002;70(3):1453–1460. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1453-1460.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu F, Chen H, Galván EM, Lasaro MA, Schifferli DM. Effects of Psa and F1 on the adhesive and invasive interactions of Yersinia pestis with human respiratory tract epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74(10):5636–5644. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00612-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Efraim S, Aronson M, Bichowsky-Slomnicki L. New antigenic component of Pasteurella pestis formed under specified conditions of pH and temperature. J Bacteriol. 1961;81(5):704–714. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.704-714.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Merriam JJ, Mueller JP, Isberg RR. The psa locus is responsible for thermoinducible binding of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis to cultured cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64(7):2483–2489. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2483-2489.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang XZ, Lindler LE. The pH 6 antigen is an antiphagocytic factor produced by Yersinia pestis independent of Yersinia outer proteins and capsule antigen. Infect Immun. 2004;72(12):7212–7219. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7212-7219.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galván EM, Nair MK, Chen H, Del Piero F, Schifferli DM. Biosafety level 2 model of pneumonic plague and protection studies with F1 and Psa. Infect Immun. 2010;78(8):3443–3453. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00382-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cathelyn JS, Crosby SD, Lathem WW, Goldman WE, Miller VL. RovA, a global regulator of Yersinia pestis, specifically required for bubonic plague. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(36):13514–13519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603456103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindler LE, Klempner MS, Straley SC. Yersinia pestis pH 6 antigen: Genetic, biochemical, and virulence characterization of a protein involved in the pathogenesis of bubonic plague. Infect Immun. 1990;58(8):2569–2577. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2569-2577.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payne D, Tatham D, Williamson ED, Titball RW. The pH 6 antigen of Yersinia pestis binds to beta1-linked galactosyl residues in glycosphingolipids. Infect Immun. 1998;66(9):4545–4548. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4545-4548.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iriarte M, et al. The Myf fibrillae of Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9(3):507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runco LM, Myrczek S, Bliska JB, Thanassi DG. Biogenesis of the fraction 1 capsule and analysis of the ultrastructure of Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(9):3381–3385. doi: 10.1128/JB.01840-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindler LE, Tall BD. Yersinia pestis pH 6 antigen forms fimbriae and is induced by intracellular association with macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8(2):311–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salih O, Remaut H, Waksman G, Orlova EV. Structural analysis of the Saf pilus by electron microscopy and image processing. J Mol Biol. 2008;379(1):174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arondel V, Benning C, Somerville CR. Isolation and functional expression in Escherichia coli of a gene encoding phosphatidylethanolamine methyltransferase (EC 2.1.1.17) from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(21):16002–16008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilpper-Bälz R, Wenzig P, Schleifer KH. Molecular relationships and classification of some viridans streptococci as Streptococcus oralis and emended description of Streptococcus oralis (Bridge and Sneath 1982) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35(4):482–488. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakenbeck R, Madhour A, Denapaite D, Brückner R. Versatility of choline metabolism and choline-binding proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae and commensal streptococci. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33(3):572–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boraston AB, Bolam DN, Gilbert HJ, Davies GJ. Carbohydrate-binding modules: Fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem J. 2004;382(Pt 3):769–781. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laughrey ZR, Kiehna SE, Riemen AJ, Waters ML. Carbohydrate-pi interactions: What are they worth? J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(44):14625–14633. doi: 10.1021/ja803960x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dougherty DA, Stauffer DA. Acetylcholine binding by a synthetic receptor: implications for biological recognition. Science. 1990;250(4987):1558–1560. doi: 10.1126/science.2274786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hermoso JA, et al. Insights into pneumococcal pathogenesis from the crystal structure of the modular teichoic acid phosphorylcholine esterase Pce. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12(6):533–538. doi: 10.1038/nsmb940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padlan EA, Davies DR, Rudikoff S, Potter M. Structural basis for the specificity of phosphorylcholine-binding immunoglobulins. Immunochemistry. 1976;13(11):945–949. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(76)90239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wah DA, Fernández-Tornero C, Sanz L, Romero A, Calvete JJ. Sperm coating mechanism from the 1.8 A crystal structure of PDC-109-phosphorylcholine complex. Structure. 2002;10(4):505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlsson K-A. Animal glycosphingolipids as membrane attachment sites for bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:309–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Molle I, et al. Chloroplasts assemble the major subunit FaeG of Escherichia coli F4 (K88) fimbriae to strand-swapped dimers. J Mol Biol. 2007;368(3):791–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li YF, et al. Structure of CFA/I fimbriae from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(26):10793–10798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812843106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole ST, et al. Donor strand complementation governs intersubunit interaction of fimbriae of the alternate chaperone pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63(5):1372–1384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zavialov AV, et al. Structure and biogenesis of the capsular F1 antigen from Yersinia pestis: preserved folding energy drives fiber formation. Cell. 2003;113(5):587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.