Abstract

Background

A spinal osteoid osteoma is a rare benign tumor. The usual treatment involves complete curettage including the nidus. In the thoracic spine, conventional open surgical treatment usually carries relatively high surgical risks because of the close anatomic relationship to the spinal cord, nerve roots, and thoracic vessels, and pulmonary complications and postoperative pain.

Case Report

We report the case of a 16-year-old girl with a symptomatic osteoid osteoma at the T9 level whose lesion was currettaged using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) guided by a navigation system (VATS-NAV). There were no complications and the patient had immediate relief of the characteristic pain after surgery and was asymptomatic at 5 months’ followup.

Literature Review

Progressive advances in the technology of spinal surgery have evolved to offer greater safety and less morbidity for patients. The advent of minimally invasive surgery has expanded the indications for VATS for anterior spinal disorders. Spinal navigation systems have become useful tools allowing localization and excision of the nidus of osteoid osteomas with minimal bone resection and without radiation exposure.

Clinical Relevance

The VATS-NAV combination in our patient allowed accurate localization and guidance for complete excision of a spinal osteoid osteoma through a minimally invasive approach without compromising spinal stability.

Introduction

An osteoid osteoma is a benign skeletal neoplasm composed of osteoid and woven bone that accounts for approximately 12% of benign skeletal neoplasms arising in the cortex of long bones. The majority of osteoid osteomas occur in children and adolescents, with spinal involvement in 10% to 20% of cases [13]. The most commonly affected part of the vertebrae is the neural arch in 75% of cases of spinal osteoid osteomas, with 33% involving the lamina, 20% involving the articular facets, and 15% involving the pedicles [43]. Osteoid osteomas located in the thoracic spine and particularly involving the vertebral body are even rarer [19]. Although most patients with adolescent scoliosis have little or no pain, osteoid osteomas are the most common cause in 2/3 of patients with painful scoliosis [17]. Patients with a spinal osteoid osteoma usually are treated successfully nonoperatively [8], and spontaneous healing of an osteoid osteoma may still occur within 3 to 4 years [24, 31]. Surgery generally is recommended for patients who do not respond to treatment with antiinflammatory drugs or when the tumor results in neural compression with deficits [8, 24, 33, 45].

However, anterior spinal surgery is a major and invasive option for treating osteoid osteomas of the vertebral bodies. The anterior approach to the thoracic spine traditionally has been gained by a posterolateral thoracotomy or a thoracolumbar incision, according to the affected level. Although the approach allows adequate exposure for curettage, there is the potential for substantial postoperative morbidity, including pain and compromised pulmonary function [7, 16]. Technologic advancements in endoscopic surgery have revolutionized traditional surgical approaches [3]. To date, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) has become a key to minimally invasive or access surgical approaches for a wide variety of anterior lesions in the thoracic spine [11, 25, 26, 44]. Video-assisted thoracic surgery has been used to perform a thoracic discectomy, resection of a spinal tumor, removal of an ossified posterior longitudinal ligament, spinal fusion, fractures, corpectomy, and spinal deformities [22, 26, 28, 44].

Even with video-assisted surgery, concerns regarding violation of the spinal canal leading to potential harm to vascular, neural, and other vital structures have resulted in techniques to improve the accuracy of spinal procedures [23, 25]. Several groups [4, 12, 15, 42] have reported a spinal navigation system (NAV) provides precise localization of the anatomy structures and instruments with minimal radiation exposure. These studies suggest accuracy of approximately 95% and reliability to reduce the margin of error in spinal surgery, such as pedicle screw insertion and resection of a spinal tumor with minimal bone removal. The demands concerning accuracy and less morbidity of spinal procedures have led surgeons to combine these newer technologies with their previous surgical arsenal [12, 39].

Preoperative image-guided localization associated with VATS has been reported as a useful therapeutic tool in the management of thoracic disease [9, 10, 36]. Although combining these techniques is not a new concept, its use in spine surgery has not been reported. We report a case of osteoid osteoma curettage in the thoracic spine performed with VATS combined with NAV (VATS-NAV).

Case Report

A 16-year-old girl was referred to our hospital with a 9-month history of mild left thoracic scoliosis (Fig. 1) and persisting dorsal thoracic pain that did not respond to NSAIDs. There was no history of injury. Her neurologic examinations and laboratory data revealed no abnormalities. CT and bone scintigraphy suggested an osteoid osteoma at the T9 level (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

An AP view radiograph of the thoracic spine shows mild left scoliosis.

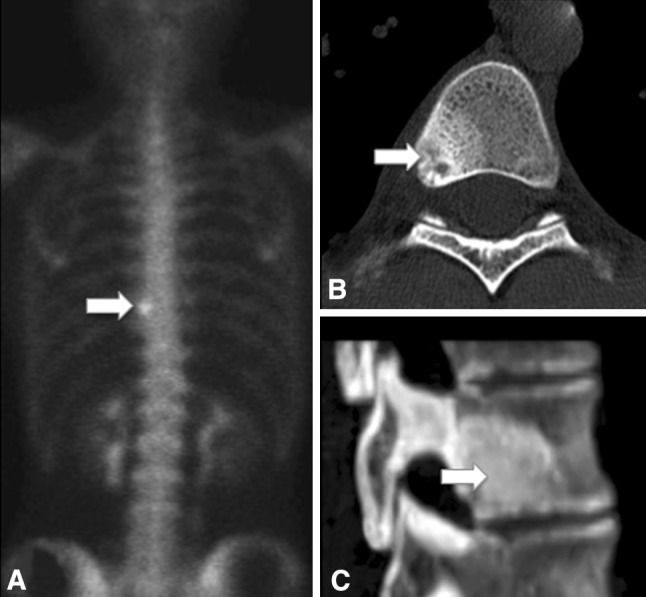

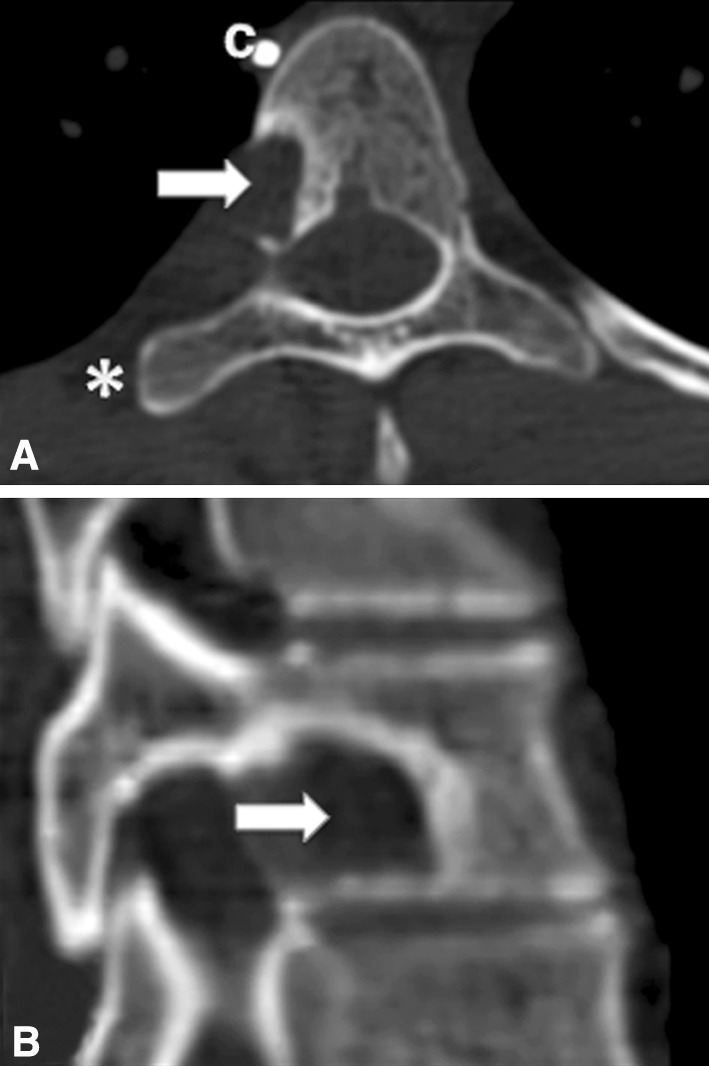

Fig. 2A–C.

(A) A bone scan shows focal increased tracer uptake (arrow) of the T9 vertebral body. (B) Axial and (C) sagittal CT scans of the spine show a nidus (12 mm × 10 mm × 8 mm) and its surrounding sclerosis (arrow).

As nonoperative treatment was ineffective, we planned lesion curettage using VATS-NAV. The patient received general anesthesia and was placed in the left lateral decubitus position. Once the T9 level was identified under fluoroscopic control, entry points were drawn on the skin for performing a four-portal technique. The spinous process of the T9 vertebra was identified and marked on the skin for the transoperative attachment of the dynamic tracking device of the navigation-read instrument (Fig. 3). The navigation system we used was StealthStation® (Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN, USA).

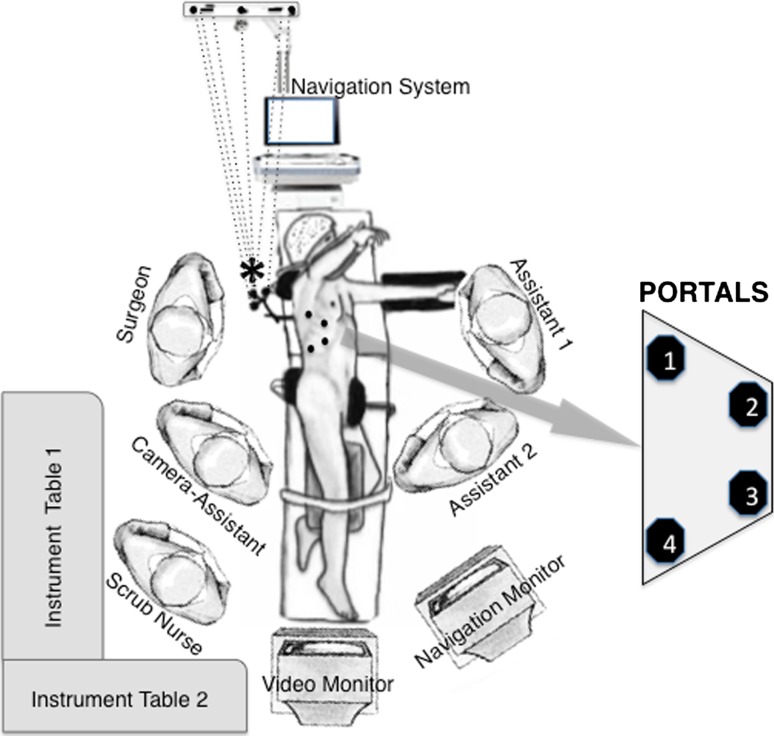

Fig. 3.

The intraoperative setup of the VATS-NAV procedure is shown in this diagram. The dynamic tracking device of the navigation-read instrument is attached to the T9 spinous process (*). The dots represent the location of the portals.

We then checked the location of the nidus and planned the entry point and projection of a hole toward the lesion (Fig. 4). To access the spinal canal and vertebral body, the rib head and proximal 3 cm of the ribs of the target lesion were removed. Using a 3-mm high-speed diamond burr, total nidus curettage was completed (Fig. 5). The surgical time was 60 minutes and the total time in the operating room was 90 minutes.

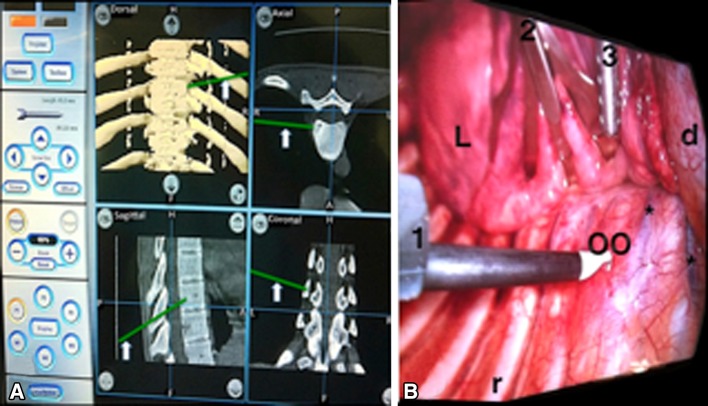

Fig. 4A–B.

(A) The NAV monitor shows the pointer (arrow) on the osteoid osteoma of the T9 vertebral body. (B) A VATS view shows a congruent image with NAV. 1 = working channel; 2 retractor channel; 3 = suction/irrigation channel; L = lung; d = diaphragm; r = rib; OO = osteoid osteoma; * = segmental vessels.

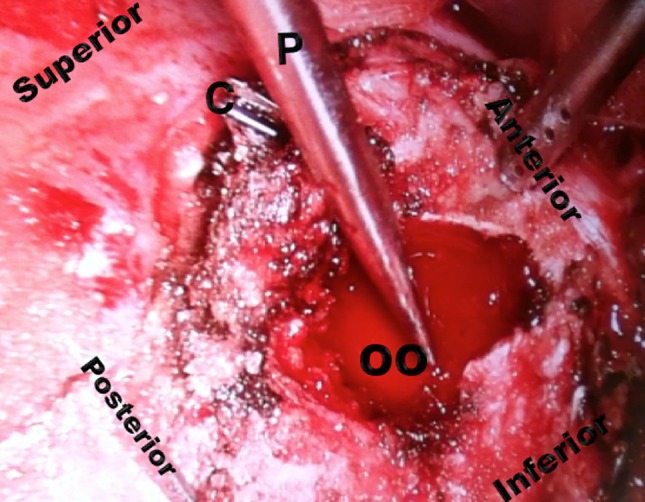

Fig. 5.

A postoperative VATS view of the osteoid osteoma after total nidus curettage is shown. C = vascular clip; P = pointer of NAV; OO = osteoid osteoma.

The patient reported immediate complete relief of preoperative pain and required only mild analgesics for postoperative pain related to the chest drain. On the second postoperative day, the chest drain was removed and the patient was discharged from the intensive care unit after review of a chest radiograph. She was allowed early mobilization without walking aids and received respiratory physiotherapy during hospitalization. The patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. She had improvement of scoliosis and was free of symptoms 5 months after treatment. CT scans at that time showed complete removal of the nidus without spinal instability (Fig. 6). Histologic examination revealed the typical structures for an osteoid osteoma.

Fig. 6A–B.

(A) Axial and (B) sagittal CT scans of the T9 vertebral body show the nidus curettage (arrow). C = vascular clip; * = removed rib.

Discussion

Patients with an osteoid osteoma can be treated successfully nonoperatively, and spontaneous healing of an osteoid osteoma may occur. However, some patients cannot tolerate such long-term nonoperative treatment. If nonoperative treatment fails, the subsequent alternative would be surgery. Currently percutaneous radiofrequency ablation is the minimally invasive surgery recommended if the site of the osteoid osteoma permits [29], as in an osteoid osteoma located in the extremities. However, an osteoid osteoma located in the posterior arch, pedicle, or posterior wall of the vertebral body carries a high surgical risk of neurovascular damage (thermal damage) because the target is close to the spinal cord, nerve roots, and arteries [34]. For this reason, we selected surgical resection of the nidus using VATS-NAV for our patient.

VATS allows for access to anterior spinal lesions using minimally invasive principles. The literature suggests VATS can be performed with the same accuracy and completeness as is possible with the conventional open approach but through much smaller skin and muscle incisions [6]. This procedure is associated with less postoperative pain, better cosmesis, earlier return to normal activity, and lower perioperative morbidity such as blood loss and pulmonary complications [3]. The disadvantages of the thoracoscopic approach are the steep learning curve [25], keeping up with evolving surgical technique and instrumentation, and higher costs [41].

Numerous studies have described the use of video-assisted surgery in the management of spinal tumors [1, 18, 23, 27, 37], however we found few studies regarding primary tumors of the spine. Mori et al. [28] in 2011 described en bloc extirpation for an osteoid osteoma of a thoracic vertebral body through a thoracoscopic approach (without NAV). Our experience with endoscopic excision of spinal osteoid osteomas was reported [2, 14], but we had not yet used the NAV system.

In general, the intent of NAV is to improve the accuracy of spine surgery. Studies comparing conventional and computer navigation techniques have shown the superior accuracy of this technology [39]. However, few studies [4, 12, 15, 42] document the accuracy of NAV for spinal tumors. Publications concerning primary tumors are even rarer; to date, three papers have reported a total of 12 patients with spinal osteoid osteomas treated with the assistance of NAV [20, 32, 40]. Assaker et al. [5] reported two cases of image-guided endoscopic spine surgery but not for tumors.

Traditionally curative treatment of a spinal osteoid osteoma could be performed using VATS after initial fluoroscopic guidance. However intraoperative localization of the nidus is often difficult. A wide surgical resection of the bony structure is required to ensure removal of the nidus [35, 38]. Therefore, the NAV system may guide intraoperative nidus resection with good accuracy, resulting in complete intralesional excision without sacrificing more bone than necessary thus resulting in instability of the spine [30]. Intraoperative CT guidance or iso-C three-dimensional intraoperative spinal navigation in our patient could have provided the ability to resect a lesion [21, 32], but with much more radiation exposure than with the NAV system that required only initial fluoroscopic localization of the vertebral target. The surgery also could have been performed using VATS alone. However, we do not believe the endoscopic view from VATS alone is adequate to delineate safely the tumor margins and its relationship with some adjacent structures. We found NAV provided adequate orientation to the surgeon with sufficient accuracy on the anatomic landmarks that were identified preoperatively with the NAV system workstation (Fig. 4). It facilitated precise planning of the curettage and the surgical vector to the targeted small and subcortical lesion at the T9 level. It also helped to define the tumor margins, limits of curettage, and the adjacent spinal canal. Moreover, the NAV system has other advantages over conventional fluoroscopic guidance such as three-dimensional (3-D) visualization of structures, the spatial relationship between instruments and anatomy in real-time, and especially, no radiation exposure.

Curative treatment of a spinal osteoid osteoma can be performed with VATS after initial fluoroscopic guidance. However intraoperative localization of the nidus is often difficult. A wide surgical resection of the bony structure is mandatory to ensure removal of the nidus. Therefore, the NAV system may guide intraoperative nidus resection with good accuracy resulting in complete intralesional excision without sacrificing more bone than necessary. An intraoperative CT in this case could present the same result, but with much more radiation exposure than the NAV system with only initial fluoroscopic localization of the vertebral target.

However, caution is needed concerning NAV. First, accurate and reliable navigation requires a low system error and high rate of congruence between the patient’s preoperative 3-D images and the surgical anatomy. The frame of reference has to be attached to the vertebra in such a manner that the vertebra and the frame became one rigid body. The site of attachment may be the pedicle or spinous process of the vertebra. Obviously, attachment to the pedicle is more rigid than attachment to the spinous process, as reported previously [5]. We chose the spinous process because the osteoid osteoma covered the pedicle area on the right side and because of the lateral decubitus position of the patient. Moreover, we usually prefer to attach the frame of reference to the spinous process because usually a pedicle attachment takes time to transfer the patient from the radiology department to the operating room, as reported previously [5]. The time needed for performing VATS-NAV in the anterior thoracic spine in our patient was approximately 2 hours, which is comparable to the time for the open procedure when performed by the same surgical team.

The second problem is that tracking of optical array devices can be obscured or displaced by surgeons and/or instruments during the procedure. If any displacement occurs during image acquisition or surgery, the whole procedure can become useless and even dangerous if the surgeon is not aware of this displacement. This also could lengthen the time of surgical procedures. During our patient’s surgery, displacement of the frame of reference attached to the T9 spinous process occurred twice. However, we did not spend much surgical time adjusting the images for the NAV. Moreover, this surgery is not totally blinded, as seen in pedicle screw insertion, because of the real-time video endoscopic view.

Progressive advances in the technology of spinal surgery have evolved to offer fewer adverse events and less morbidity for patients. We believe VATS-NAV allows spinal operations to be performed in less time with less morbidity, and minimizes the hazards of radiation for the surgeon, patient, and operating room staff. VATS-NAV provided real and virtual images of the targeted lesion and positioning of the instruments in real time. Further prospective and comprehensive studies may confirm our initial impressions regarding the VATS-NAV combination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carlo Piovani for help in acquiring the images in this work.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the reporting of this case report, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Al-Sayyad MJ, Crawford AH, Wolf RK. Early experiences with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: our first 70 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:1945–1951; discussion 1952. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Amendola L, Cappuccio M, Boriani L, Gasbarrini A. Endoscopic excision of C2 osteoid osteoma: a technical case report. Eur Spine J. 2012 Aug 7. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Anand N, Regan JJ. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for thoracic disc disease: classification and outcome study of 100 consecutive cases with a 2-year minimum follow-up period. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:871–879. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Arand M, Schempf M, Hebold D, Teller S, Kinzl L, Gebhard F. [Precision of navigation-assisted surgery of the thoracic and lumbar spine][in German] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:899–906. doi: 10.1007/s00113-003-0687-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assaker R, Reyns N, Pertruzon B, Lejeune JP. Image-guided endoscopic spine surgery: Part II. Clinical applications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1711–1718. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Bomback DA, Charles G, Widmann R, Boachie-Adjei O. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery compared with thoracotomy: early and late follow-up of radiographical and functional outcome. Spine J. 2007;7:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burd TA, Pawelek L, Lenke LG. Upper extremity functional assessment after anterior spinal fusion via thoracotomy for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: prospective study of twenty-five patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Burn SC, Ansorge O, Zeller R, Drake JM. Management of osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma of the spine in childhood. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:434–438. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.PEDS08450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Chen L, Qiang G, Chen Z, Jing J, Xiong S. Using an image-guided navigation system for localization of small pulmonary nodules before thoracoscopic surgery: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1883–1886. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W, Chen L, Yang S, Chen Z, Qian G, Zhang S, Jing J. A novel technique for localization of small pulmonary nodules. Chest. 2007;131:1526–1531. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford AH. Anterior surgery in the thoracic and lumbar spine: endoscopic techniques in children. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Torre-Gutierrez M, Martinez-Quinones JV, Escobar-Solis R, de la Torre-Gutierrez S. [Spinal neuronavigation: our experience][in Spanish] Neurocirugia (Astur). 2001;12:490–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlemann R. Imaging and differential diagnosis of primary bone tumors and tumor-like lesions of the spine. Eur J Radiol. 2006;58:48–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasbarrini A, Cappuccio M, Bandiera S, Amendola L, van Urk P, Boriani S. Osteoid osteoma of the mobile spine: surgical outcomes in 81 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:2089–2093. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Gebhard F, Weidner A, Liener UC, Stockle U, Arand M. Navigation at the spine. Injury. 2004;35(suppl 1):S-A35–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Graham EJ, Lenke LG, Lowe TG, Betz RR, Bridwell KH, Kong Y, Blanke K. Prospective pulmonary function evaluation following open thoracotomy for anterior spinal fusion in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2319–2325. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Janin Y, Epstein JA, Carras R, Khan A. Osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas of the spine. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:31–38. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kan P, Schmidt MH. Minimally invasive thoracoscopic approach for anterior decompression and stabilization of metastatic spine disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:E8. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/25/8/E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kan P, Schmidt MH. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma of the spine. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendoff D, Hufner T, Citak M, Geerling J, Mossinger E, Bastian L, Krettek C. Navigated Iso-C3D-based percutaneous osteoid osteoma resection: a preliminary clinical report. Comput Aided Surg. 2005;10:157–163. doi: 10.3109/10929080500229868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan SA, Thulkar S, Shivanand G, Kumar A, Varshney MK, Yadav CS, Rastogi S, Sharma DN. Computed tomography-guided radiofrequency ablation of osteoid osteomas. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2008;16:179–181. doi: 10.1177/230949900801600210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JS, Lee SH, Seong JY, Kim KH, Jung B. Video-assisted thoracoscopic removal of ossified posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) in the thoracic spine: a case report. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2010;53:138–141. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SJ, Sohn MJ, Ryoo JY, Kim YS, Whang CJ. Clinical analysis of video-assisted thoracoscopic spinal surgery in the thoracic or thoracolumbar spinal pathologies. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2007;42:293–299. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2007.42.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kneisl JS, Simon MA. Medical management compared with operative treatment for osteoid-osteoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu GK, Kit WH. Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery for spinal conditions. Neurol India. 2005;53:489–498. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.16939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lonner BS, Auerbach JD, Estreicher M, Milby AH, Kean KE, Panagopoulos G, Chang D. Video-assisted anterior thoracoscopic spinal fusion versus posterior spinal fusion: a comparative study utilizing the SRS-22 outcome instrument. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:193–198. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.McLain RF. Spinal cord decompression: an endoscopically assisted approach for metastatic tumors. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:482–487. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori K, Imai S, Saruhashi Y, Matsusue Y. Thoracoscopic en bloc extirpation for subperiosteal osteoid osteoma of thoracic vertebral body: a rare variety and its therapeutic consideration. Spine J. 2011;11:e13–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motamedi D, Learch TJ, Ishimitsu DN, Motamedi K, Katz MD, Brien EW, Menendez L. Thermal ablation of osteoid osteoma: overview and step-by-step guide. Radiographics. 2009;29:2127–2141. doi: 10.1148/rg.297095081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagashima H, Nishi T, Yamane K, Tanida A. Case report: osteoid osteoma of the C2 pedicle: surgical technique using a navigation system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:283–288. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0958-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann D, Dorn U. Osteoid osteoma of the dens axis. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(suppl 3):271–274. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0332-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajasekaran S, Kamath V, Shetty AP. Intraoperative iso-C three-dimensional navigation in excision of spinal osteoid osteomas. Spine (Phila PA 1976). 2008;33:E25–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ropper AE, Cahill KS, Hanna JW, McCarthy EF, Gokaslan ZL, Chi JH. Primary vertebral tumors: a review of epidemiologic, histological, and imaging findings: Part I. Benign tumors. Neurosurgery. 2011;69:1171–1180. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31822b8107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Torriani M, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Osteoid osteoma: percutaneous treatment with radiofrequency energy. Radiology. 2003;229:171–175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291021053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaffer V, Wegener B, Durr HR. Classical surgical resection of osteoid osteoma of the cervical spine. Acta Chir Belg. 2010;110:603–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spirn PW, Shah RM, Steiner RM, Greenfield AL, Salazar AM, Liu JB. Image-guided localization for video-assisted thoracic surgery. J Thorac Imaging. 1997;12:285–292. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.St Clair SF, McLain RF. Posterolateral spinal cord decompression in patients with metastasis: an endoscopic assisted approach. Surg Technol Int. 2006;15:257–263. [PubMed]

- 38.Sukan A, Kabatas S, Cansever T, Yilmaz C, Demiralay E, Altinors N. Osteoid osteoma in the thorasic spine. Turk Neurosurg. 2009;19:288–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tjardes T, Shafizadeh S, Rixen D, Paffrath T, Bouillon B, Steinhausen ES, Baethis H. Image-guided spine surgery: state of the art and future directions. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:25–45. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Royen BJ, Baayen JC, Pijpers R, Noske DP, Schakenraad D, Wuisman PI. Osteoid osteoma of the spine: a novel technique using combined computer-assisted and gamma probe-guided high-speed intralesional drill excision. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:369–373. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Van Schil P. Cost analysis of video-assisted thoracic surgery versus thoracotomy: critical review. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:735–738. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang DJ, Yang J, Zhao JZ, Zhao YL. [Application of computer-assistant neuronavigation in spinal operation][in Chinese] Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2004;84:1554–1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells RG, Miller JH, Sty JR. Scintigraphic patterns in osteoid osteoma and spondylolysis. Clin Nucl Med. 1987;12:39–44. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198701000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yanni DS, Connery C, Perin NI. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery combined with a tubular retractor system for minimally invasive thoracic discectomy. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(1 suppl operative):138–143; discussion 143. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Zileli M, Cagli S, Basdemir G, Ersahin Y. Osteoid osteomas and osteoblastomas of the spine. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]