Abstract

Objective

The aim of this paper was to show that easily interpretable maps of local and national prescribing data, available from open sources, can be used to demonstrate meaningful variations in prescribing performance.

Design

The prescription dispensing data from the National Health Service (NHS) Information Centre for the medications metformin hydrochloride and methylphenidate were compared with reported incidence data for the conditions, diabetes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, respectively. The incidence data were obtained from the open source general practitioner (GP) Quality and Outcomes Framework. These data were mapped using the Ordnance Survey CodePoint Open data and the data tables stored in a PostGIS spatial database. Continuous maps of spending per person in England were then computed by using a smoothing algorithm and areas whose local spending is substantially (at least fourfold) and significantly (p<0.05) higher than the national average are then highlighted on the maps.

Setting

NHS data with analysis of primary care prescribing.

Population

England, UK.

Results

The spatial mapping demonstrates that several areas in England have substantially and significantly higher spending per person on metformin and methyphenidate. North Kent and the Wirral have substantially and significantly higher spending per child on methyphenidate.

Conclusions

It is possible, using open source data, to use statistical methods to distinguish chance fluctuations in prescribing from genuine differences in prescribing rates. The results can be interactively mapped at a fine spatial resolution down to individual GP practices in England. This process could be automated and reported in real time. This can inform decision-making and could enable earlier detection of emergent phenomena.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Primary Care, Spatio-temporal mapping

Article summary.

Article focus

Open source data were used to map prescribing in primary care in England.

Continuous maps of spending per person were computed and a smoothing algorithm applied.

Areas with significantly higher spending than the national average were identified for the medications methylphenidate and metformin.

Key messages

It is possible to produce easily interpretable maps of local and national prescribing data from open sources in England.

Statistical methods can be used to distinguish chance fluctuations in prescribing from genuine difference.

This mapping can go down a fine spatial resolution and has the potential to inform decision-making in real time.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first time these prescribing data have been mapped since the National Health Service (NHS) Information Centre made it freely available in September 2011.

This mapping has been entirely produced using open sources of data.

There is still a lag in the release of NHS data and this restricts the current opportunities for the early detection of emergent phenomena.

This means this is currently a snapshot spatial analysis and not a continuously updated spatio-temporal analysis.

There is currently no linkage of these data to other data streams, such as small area census data, but this is theoretically possible.

Introduction

On 14 December 2011, the National Health Service (NHS) Administrative Data Liaison Service announced the free availability of monthly prescription data by general practitioner (GP) practice throughout England. These data contain costing and item counts for all prescriptions aggregated by British National Formulary (BNF)1 code for each GP practice or clinic. Linking the prescription data to location, practice geodemographics and health statistics provides a useful tool for studying health trends and for routine surveillance.

To illustrate what can be done with the data, we first look at prescription rates of metformin hydrochloride (BNF code 060102) and compare with reported incidence of diabetes from another open health data source, the GP Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) data. We then map methylphenidate prescriptions (BNF code 0404000M0) and suggest that the pattern of spatial variations in prescribing policy for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication raises some questions about equity of access or consistency of diagnosis.

Methods

Data sources

The prescription dispensing data come from the NHS Information Centre web site (http://www.ic.nhs.uk/services/transparency/prescribing-by-gp-practice). In this paper we use the first month of released data, which covers prescriptions issued in September 2011. The data are supplied as one file with over 4 million rows in comma-separated value format. Each row gives the practice code, BNF code name and number, number of items dispensed, net ingredient cost (NIC) and actual cost. In this paper we use the NIC as our measure of the amount prescribed.

The addresses of the prescribing practices can be downloaded from the same site as the prescription data. This is another comma-separated value file with about 10 000 rows. The file gives the name and address of each practice together with the NHS practice code that links it to the prescription dispensing data file.

These two data sets are released under the Open Government license (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence).

The demographics of English GP practices can be downloaded from another Information Centre web site (https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/webview), in the section on GP practice data. The site states: ‘Copyright 2011 The NHS Information Centre (General and Personal Medical Services Statistics)’ but no exact license or usage requirements are obvious. The most recent data are for August 2010, and so we used these. Each practice record has the total number of registered people, a breakdown of that number into six age categories and a further division of those age categories into male and female numbers. These data include the same practice code as used in the prescription address data. However, linking these together only matches 8221 records because the remainder of the 10 000 or so prescription address data records are places such as specialist clinics, hospitals and out-of-hours services that do not have a registration system. Visual inspection of the non-matching records confirms this from the names of the unmatched records.

A dataset of postcodes with OSGB grid reference coordinates is available from the Ordnance Survey in their ‘CodePoint Open’ product (http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/oswebsite/products/code-point-open). The license states that it is free to view, download and use under OS OpenData terms. This data matches the postcodes in the prescribing address file once the postcodes in that file have had spaces removed. For example, the code LA1 4YF appears in the Ordnance Survey data as LA14YF, with no spaces.

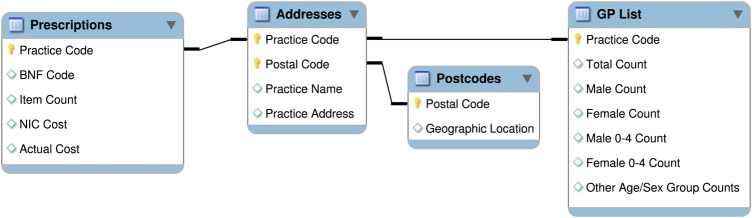

The data tables were stored in a PostGIS (http://www.postgis.org) spatial database for retrieval by GIS and statistical packages. An illustration of the database structure appears in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Database structure.

Smoothing the data

The data are based on point locations but we would like to produce continuous maps of spending per person over England. We use a smoothing algorithm whereby the value at some arbitrary location is the distance-weighted average of the spending per person at enough practices in the vicinity of that location to constitute a population of a given fixed size. We then compute this over all points on a grid over the land surface of England. SEs of the smoothed surface can also be computed (see online supplementary appendix).

The effect of this smoothing algorithm is similar to an adaptive-bandwidth kernel smoothing. In areas with a high density of practices, such as in a city, the gridded values only depend on practices within a small neighbourhood. In a sparse region the algorithm has to search over longer distances to find enough practices. The choice of population size can be made by minimising a statistical criterion such as cross-validated mean squared error, or be chosen pragmatically, for example, as a constant times the average registration size of a GP practice. We can also use the age and sex stratification of the GP list data to define a baseline population in a specific age and/or sex stratum of the population.

From our smoothed estimates and SEs we can map areas that are excessively high or low, where ‘excessively’ can be chosen as some multiple or fraction of the country-wide average rate. For example, using the values of 4 and 0.25, our maps show the one-sided p values for tests of the null hypotheses that the local rate is at most four times or at least a quarter of, respectively, the country-wide average. Areas with p values below the critical 0.05 level are then highlighted in red for high values and blue for low values.

Results

Diabetes

The QOF is an annual reward and incentive programme for all GP surgeries in England, which details practice achievement results (http://www.qof.ic.nhs.uk). In 2010/2011, QOF measured achievement against 134 indicators. The NHS Information Centre has made the information freely available and this provides easy access to comprehensive information on the pattern of chronic disease across over 54 million registered patients in England. These outcomes include the prevalence within practices for diabetes and are available for download from the NHS Information Centre website (https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/webview). The figures are published annually. For this study we use the data from October 2011. The practice code is included, so we can use the addresses and postcode tables described earlier to map point prevalence diabetes at approximate GP practice locations.

Metformin is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) as first-line treatment in obese individuals diagnosed with type 2 diabetes2 and appears in the database with BNF codes starting with 060102. This includes combination prescriptions with thiazolidinediones and other drugs. Table 1 shows the total item count and NIC spent on these drugs in the data. Because 99.8% of the prescriptions are for metformin hydrochloride on its own, we will use the total cost of that specific BNF code item (0601022B0). As a denominator for the population for each practice we use the total number of people registered from the demographic data.

Table 1.

Item count and net ingredient cost (NIC) for metformin preparations

| Name | Item count | NIC |

|---|---|---|

| Metformin hydrochloride | 1368136 | £6365177.23 |

| Metformin hydrochloride/vildagliptin | 7322 | £262662.61 |

| Metformin hydrochloride/sitagliptin | 5158 | £208765.35 |

| Metformin hydrochloride/pioglitazone | 19410 | £818763.55 |

| Metformin hydrochloride/rosiglitazone | 5 | £193.75 |

Investigation of the database shows only a relatively small amount of spending on metformin products from clinics without practice lists, not enough to materially affect the conclusions given here. Where two or more practice locations have the same post-code, we sum the spend and practice populations and compute a spend per person based on all the practices at that postcode. Similarly, for the prevalence outcome measure we can compute an overall prevalence at a location since the data contain the raw numerator and denominator values as well as the computed prevalence.

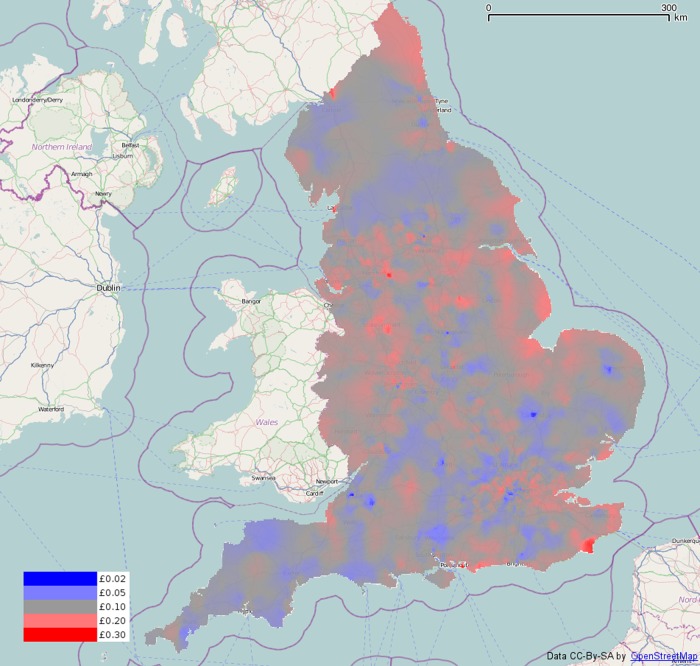

Figure 2 shows the spending per person smoothed over England using the previously described smoothing algorithm, overlaid on OpenStreetMap base data (http://www.openstreetmap.org). A population size of 100 000 was used to compute the weighted averages at each grid point. One outlying practice was found with more than 50 times the maximum spend per person of any other practice and was removed from the data.

Figure 2.

Smoothed metformin spending (net ingredient cost per person) over the whole of England.

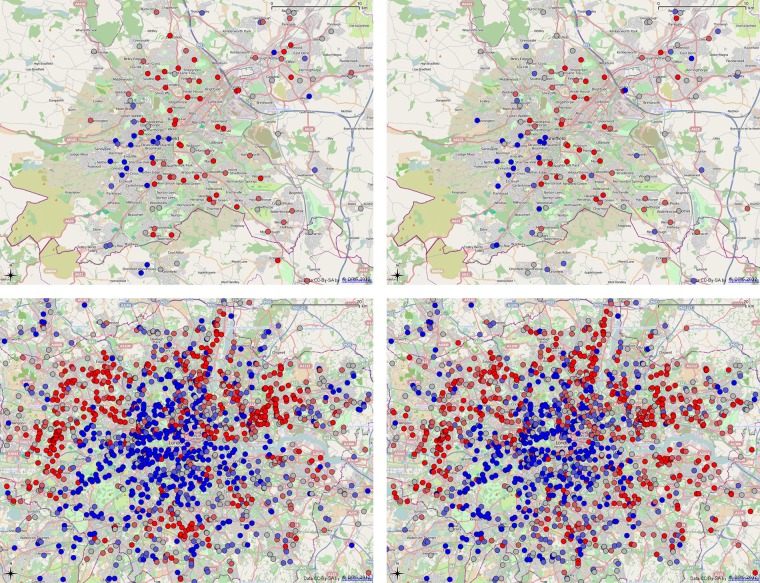

As an initial comparison of the spending data and the prevalence values we can plot point maps of the practice locations coloured according to the value. Figure 3 shows two areas, Sheffield and London, with the points coloured by categorising the points into five quintiles. The highest fifth of all points are coloured bright red, the lowest fifth are bright blue. The intermediate quintiles are coloured dull red, grey and dull blue. This serves to highlight the extreme values. Inspection of the maps in a desktop mapping package, Quantum GIS (http://www.qgis.org) showed the expected correspondence of both measures over the whole country.

Figure 3.

Diabetes prevalence (left) and metformin spending (net ingredient cost per person, right) in Sheffield (top) and London (bottom). Points are colour coded by quintiles: from bright blue (lowest), through dull blue, grey, dull red and bright red (highest).

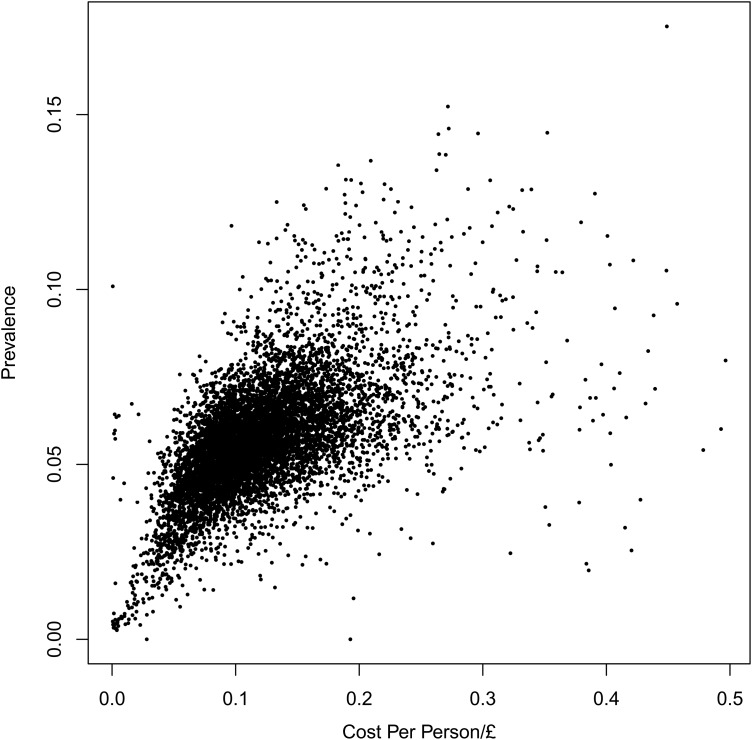

Figure 4 is a scatterplot of the metformin cost per person against the prevalence for the 8111 GP practices. To improve the clarity of the plot, 20 outlying points (with cost per-person values between £0.50 and £2.50) have been excluded. The correlation coefficient for this scatterplot is 0.49.

Figure 4.

Metformin spending (net ingredient cost per person) against prevalence for the 8111 general practitioner practices in England.

We can use the quintile classification used for colouring the map points to get another assessment of how well the metformin spending correlates with the reported prevalence. We compute a table of the difference in quintile classification for each GP practice where we have both measures. This tells us how many quintiles are exactly the same, and how many are one, two, three or four categories different in each direction. In table 2, we show the number (out of 8111) of practices in each category and the corresponding proportion.

Table 2.

Table of net ingredient cost (NIC) quintile minus prevalence quintile

| Difference | –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Number | 29 | 209 | 663 | 1628 | 3193 | 1456 | 648 | 217 | 68 |

| Proportion | 0.004 | 0.026 | 0.082 | 0.201 | 0.394 | 0.180 | 0.080 | 0.027 | 0.008 |

Positive (negative) differences correspond to practices whose NIC falls in a higher (lower) quintile than their reported prevalence.

Table 2 shows that about 80% of the practices are in either the same or adjacent quintile categories. Note that the four left-most columns of table 2 come from practices where the quintile of the cost from the dispensing database is less than the quintile from the QOF prevalence report, while the four right-most columns are where dispensing cost is in a higher quintile than the prevalence quintile.

ADHD and methylphenidate

Methylphenidate is licensed in the UK for the treatment of ADHD and is also recommended by NICE.3 Treatment with methylphenidate is usually initiated by specialists with ongoing prescriptions on a shared-care basis with general practice. Prescriptions of methylphenidate appear in the database with the BNF code of 0404000M0. This combines standard-release non-proprietary and proprietary (Ritalin) medication as well as more expensive modified-release versions.

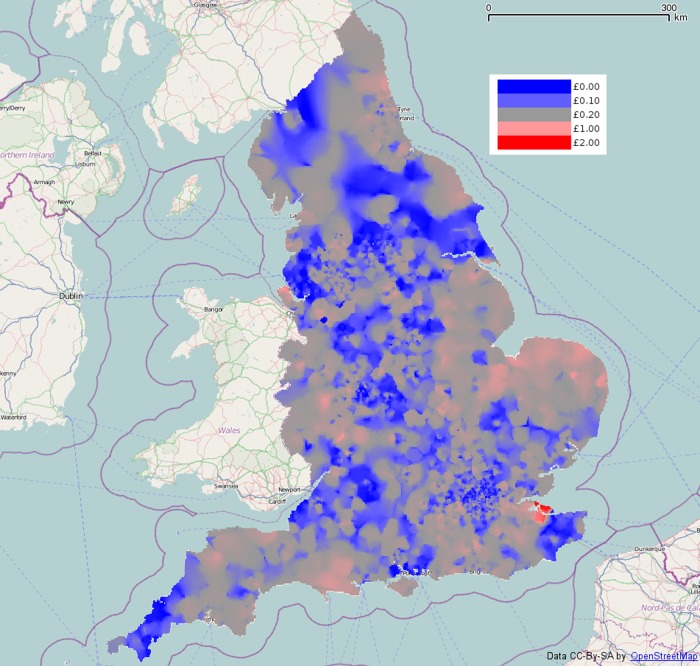

The total spending in England is just under £2 million on a total GP-registered population of 55 million adults (£0.035 per person) or 10 million children (£0.20 per under-14). Figure 5 is a map of smoothed methylphenidate spend per child, using an included population of 10 000 children aged 14 or below in the smoothing algorithm. The map is coloured so that grey is the national average, while blue and red are below and above the national average, respectively.

Figure 5.

Smoothed methylphenidate spending (net ingredient cost per child) over the whole of England.

This map shows a few high spots, the highest being in north Kent. Figure 6 shows areas significantly above four times the national average in red. The area in north Kent is above this threshold, as is a small area on the Wirral peninsula, and a tiny area in Norwich. Nowhere on the map is significantly below one-quarter of the national average rate.

Figure 6.

Areas whose smoothed methylphenidate spending (net ingredient cost per child) is significantly above four times the national average (p=0.05).

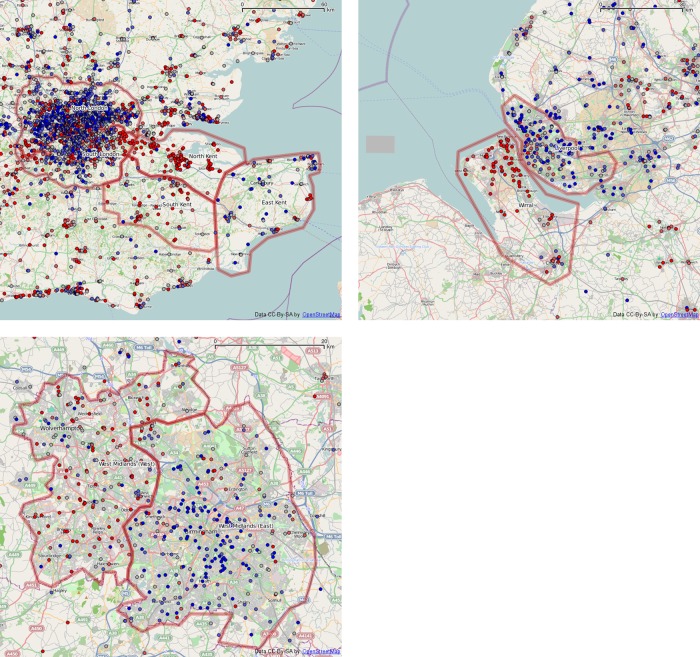

It is possible that substantial spending on methylphenidate comes from specialist clinics rather than GPs with a registered list. Without a measure of the size of these clinics we cannot work out how many children are being served. However, we can aggregate spending from all sources within regions and compare across regions. Table 3 shows the top 10 spending locations for practices with and without registered lists. This shows that we cannot neglect the spending from the clinics in any assessment of the geographic spending pattern. In each part of figure 7 we show points coloured by methylphenidate spending per child on each GP register. Overlaid on each map are some ad hoc regions within which we can find the total spend from both GP practices with registration lists and from clinics without registers. As a denominator we can take the total number of children or people registered to GPs in those regions, and then produce the spend per child or per person within each region.

Table 3.

Top 10 methylphenidate dispensers by net ingredient cost (NIC), with and without a register

| Sources with a register (mostly general practices) | Sources without a register (mostly clinics) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NIC (£) | Location | NIC (£) | Location |

| 3671.96 | The OM Medical Centre, Kent | 7929.60 | The Child Health Unit, Essex |

| 3456.41 | St. Georges Medical Centre, Kent | 4398.76 | Community Paediatricians, Coventry |

| 3233.68 | Wensum Valley Medical Practice, Norfolk | 3437.39 | CAMHS Gulson Clinic, London |

| 2762.95 | Vida Healthcare, Norfolk | 3379.84 | CAMHS, Chesterfield |

| 2640.42 | Coastal Medical Group, Lewes | 3020.84 | CAMHS Whitestone Clinic, Warwickshire |

| 2598.96 | Dr Wilczynski & Partners, Northamptonshire | 2814.99 | CAMHS, West Lancashire |

| 2547.77 | The Chestnuts Surgery, Kent | 2445.07 | Children's Centre, Middlesex |

| 2430.84 | Mantgani AB & Partners, Wirral | 2229.33 | Community Paediatricians, Worcestershire |

| 2415.55 | Woodlands Family Practice, Kent | 2060.11 | CAMHS, Worcester, Worcestershire |

| 2342.61 | St. James Medical Practice, Norfolk | 1752.52 | Drug Clinic (Sch), Birkenhead |

Figure 7.

Methylphenidate spending (net ingredient cost per child) in selected regions. Points are colour coded by quintiles: from bright blue (lowest), through dull blue, grey, dull red and bright red (highest).

As well as comparing parts of Kent and parts of Merseyside, where the two most extreme prescribing rates are locates, we examine divisions of the two most populated areas of England, namely London and the West Midlands. A visual inspection of the West Midlands shows some increased spending in the western area, but London does not show any comparably simple geographical trend. The table of spending computed from all GP and non-GP sources for these regions will show if those non-GP sources make a substantial contribution to overall spending here. Table 4 shows the spending per child and per person in those regions as well as the England-wide average. The highly increased spending in North Kent and the Wirral is still evident compared with nearby regions, even with the added non-GP spending. A preliminary analysis of the October 2011 data shows similar behaviour to the September 2011 data.

Table 4.

Regional methylphenidate spending (net ingredient cost, NIC) per child and per person, by region

| Region | Per child (£) | Per person (£) |

|---|---|---|

| North Kent | 0.724 | 0.133 |

| South Kent | 0.322 | 0.157 |

| East Kent | 0.118 | 0.020 |

| Wirral | 0.604 | 0.099 |

| Liverpool | 0.074 | 0.012 |

| West Midlands (West) | 0.304 | 0.054 |

| West Midlands (East) | 0.074 | 0.015 |

| London (North) | 0.117 | 0.021 |

| London (South) | 0.170 | 0.030 |

| England average | 0.207 | 0.035 |

Discussion

We have shown that the newly released data can be used to produce maps of prescribing data across England. These maps can reveal geographical variations in prescribing patterns that are not immediately apparent and may be clinically significant. Spatial analysis has been used in Taiwan to demonstrate the heterogeneity of cardiovascular drug prescribing but this was at a coarser spatial resolution (over 352 townships).4 It also focused on testing for departure from spatial homogeneity of prescribing rates, rather than on estimation of relative rates, but it was able to pick up a clear disparity between northern and southern regions. An analysis in the USA looked at geographic variation in prescribing decisions in diabetes.5 It was conducted at the level of hospital referral region (n=306) and used regression models to investigate the relationships between prescribing rates and sociodemographic risk factors such as ethnicity, gender and income.

The strength of this analysis is that it shows how a statistical method can be used to distinguish chance fluctuations from genuine differences in prescribing rates. Interactive mapping of the results can be accomplished and analysis can be automated, hence conducted and reported in real-time. The data from this analysis are comprehensive, and at fine (individual GP practice-level) spatial resolution across all of England.

The major limitations of the data are that they are only available at a monthly time resolution and that there is an 11-week time-lag in the release of the data. The results presented here can therefore only provide a snap-shot spatial analysis rather than a continuously updated spatio-temporal analysis. There is no automatic linkage to other relevant data-streams, for example, NHS111 or small-area census data, but linkage to these is straightforward in principle.

Methyphenidate is not the only medication that can be used for ADHD. NICE have suggested atomoxetine and dexamfetamine are options medical professionals may wish to consider in more complex cases. Methylphenidate is prescribed much more frequently than the other recommended medications for ADHD. Our initial investigations showed that the data for atomoxetine and dexamfetamine are dominated by GPs with zero prescriptions. Preliminary investigation at the regions of interest shows some spatial patterns that match those for methyphenidate; but the small numbers make formal analysis problematic. In addition, methylphenidate may also be used in other conditions and it is an unlicensed treatment option in narcolepsy. It is not possible to match diagnoses to medications in these datasets and this should be recognised as a limitation in the interpretation of the results.

There are some limitations in the GP patient age breakdown with groups being split into ages 0–4 and 5–14. We have mapped these two groups together. While methylphenidate does not have a license for use in children under age 6 it is still used. The data provide a good approximation of a young population but we are limited by the age categories and they do not provide information on prescribing in older adolescents and adulthood.

Data relating to all aspects of healthcare systems are now routinely collected and stored electronically, but all-too-rarely analysed. This represents a lost opportunity because in any complex system, continuous monitoring of performance is key to process improvement.6 Analysing health-related outcomes in real time can provide early identification of anomalies in the overall pattern of variation while distinguishing between chance fluctuations and genuine differences in system performance. This, in turn, can inform decision-making, either to allocate resources in order to deal with an acute problem, or to address systemic weaknesses.

Our results show how modern statistical methods can be used to convert spatially resolved prescribing data into easily interpretable maps of local and national variations in the underlying prescribing rates of individual prescription items or groups of clinically related items. Often, statistically significant variations in prescribing rates can be at least partly explained by geographical variations in known risk factors for particular conditions. The simple smoothing method described here can then be extended to a semiparametric regression model7 that decomposes the observed prescribing rate at any location into a multiple regression term with the known risk factors as covariates, a term for unexplained spatial variation that may warrant further investigation, and a spatially unstructured residual.

The government is to be congratulated for making publicly available the data required for this analysis. The value of the data would, however, be greatly increased if future releases could be made more frequently and more quickly. The current frequency is monthly, while the data relating to September 2011 were released almost 11 weeks later, on 14 December. Increasing the frequency from monthly to weekly, and reducing the delay between the end of each reporting period and the release of the corresponding data, would enable earlier detection of emergent phenomena, such as localised outbreaks of food-borne disease or seasonal influenza epidemics.

A single week's data might be too sparse in themselves to detect more than the most obvious variations in underlying prescribing rates. However, the same statistical modelling principles that we have used here to smooth out chance geographical variations in prescribing rates by discounting spatially referenced information according to increasing distance from the location of interest could be applied to smooth out chance temporal variations by discounting past information according to its age. In some contexts, a further increase in frequency to daily releases would be even better; we have previously demonstrated this in using daily records of calls to NHS Direct for real-time syndromic surveillance.8 9 In the current context, the natural rhythms of the working week make it harder to argue that daily reporting of prescription rates would generally be any more informative of the incidence or prevalence of related health conditions than would weekly reporting.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PD, BR, EL and BT were all involved in the initial conception of the study. BR and BT ran the statistical analysis and performed the mapping of the data. PJD wrote the initial draft and all authors contributed to the subsequent and final drafts. PJD is the guarantor.

Funding: This was funded by Medical Research Grant. Details of funding: Medical Research Council grant G0-02153 awarded to Peter J. Diggle and Barry Rowlingson.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This study uses only publicly available data. All the data used in this study are available from open sources and these are detailed in the article text.

References

- 1.Joint Formulary Committee British National Formulary. 62nd edn. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2011. ISBN 085369981X. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Type 2 diabetes: newer agents for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes, 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG87ShortGuideline (accessed 1 February 2012).

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder—diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults, 2009. http://www.nice.org.uk/CG072 (accessed 1 February 2012). [PubMed]

- 4.Cheng CL, Chen YC, Liu TM, et al. Using spatial analysis to demonstrate the heterogeneity of the cardiovascular drug-prescribing pattern in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2011;11:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sargen MR, Hoffstad OJ, Wiebe DJ, et al. Geographic variations in pharmacotherapy decisions for U.S. medicare enrollees with diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2012;26:301–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deming WE. Out of the crisis. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ. Generalized additive models. London: Chapman & Hall, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diggle P, Rowlingson B, Su T. Point process methodology for on-line spatio-temporal disease surveillance. Environmetrics 2005;16:423–34 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diggle P, Knorr-Held L, Rowlingson B, et al. On-line monitoring of public health surveillance data. In: Brookmyer R, Stroud DF, eds. Monitoring the health of populations: statistical principles and methods for public health surveillance. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:233–66 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.