Abstract

Objective

To explore evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness outcomes.

Design

Systematic review.

Setting

A wide range of settings within primary and secondary care including hospitals and primary care centres.

Participants

A wide range of demographic groups and age groups.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

A broad range of patient safety and clinical effectiveness outcomes including mortality, physical symptoms, length of stay and adherence to treatment.

Results

This study, summarising evidence from 55 studies, indicates consistent positive associations between patient experience, patient safety and clinical effectiveness for a wide range of disease areas, settings, outcome measures and study designs. It demonstrates positive associations between patient experience and self-rated and objectively measured health outcomes; adherence to recommended clinical practice and medication; preventive care (such as health-promoting behaviour, use of screening services and immunisation); and resource use (such as hospitalisation, length of stay and primary-care visits). There is some evidence of positive associations between patient experience and measures of the technical quality of care and adverse events. Overall, it was more common to find positive associations between patient experience and patient safety and clinical effectiveness than no associations.

Conclusions

The data presented display that patient experience is positively associated with clinical effectiveness and patient safety, and support the case for the inclusion of patient experience as one of the central pillars of quality in healthcare. It supports the argument that the three dimensions of quality should be looked at as a group and not in isolation. Clinicians should resist sidelining patient experience as too subjective or mood-oriented, divorced from the ‘real’ clinical work of measuring safety and effectiveness.

Keywords: patient experience, Patient safety

Article summary.

Article focus

Should patient experience, as advocated by the Institute of Medicine and the NHS Outcomes Framework, be seen as one of the pillars of quality in healthcare alongside patient safety and clinical effectiveness?

What aspects of patient experience can be linked to clinical effectiveness and patient safety outcomes?

What evidence is available on the links between patient experience and clinical effectiveness and patient safety outcomes?

Key messages

The results show that patient experience is consistently positively associated with patient safety and clinical effectiveness across a wide range of disease areas, study designs, settings, population groups and outcome measures.

Patient experience is positively associated with self-rated and objectively measured health outcomes; adherence to recommended medication and treatments; preventative care such as use of screening services and immunisations; healthcare resource use such as hospitalisation and primary-care visits; technical quality-of-care delivery and adverse events.

This study supports the argument that patient experience, clinical effectiveness and patient safety are linked and should be looked at as a group.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study demonstrates an approach to designing a systematic review for the ‘catch-all’ term patient experience, and brings together evidence from a variety of sources that may otherwise remain dispersed.

This was a time-limited review and there is scope to expand this search based on the results and broaden the search terms to uncover further evidence.

Introduction

Patient experience is increasingly recognised as one of the three pillars of quality in healthcare alongside clinical effectiveness and patient safety.1 In the NHS, the measurement of patient experience data to identify strengths and weaknesses of healthcare delivery, drive-quality improvement, inform commissioning and promote patient choice is now mandatory.2–4 In addition to data on harm avoidance or success rates for treatments, providers are now assessed on aspects of care such as dignity and respect, compassion and involvement in care decisions.4 In England, these data are published in Quality Accounts and the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation payment framework which makes a proportion of care providers’ income conditional on the improvement in this domain.5

The inclusion of patient experience as a pillar of quality is often justified on grounds of its intrinsic value—that the expectation of humane, empathic care is requires no further justification. It is also justified on more utilitarian grounds as a means of improving patient safety and clinical effectiveness.6 7 For example, clear information, empathic, two-way communication and respect for patients’ beliefs and concerns could lead to patients being more informed and involved in decision-making and create an environment where patients are more willing to disclose information. Patients could have more ‘ownership’ of clinical decisions, entering a ‘therapeutic alliance’ with clinicians. This could support improved and more timely diagnosis, clinical decisions and advice and lead to fewer unnecessary referrals or diagnostic tests.8 9 Increased patient agency can encourage greater participation in personal care, compliance with medication, adherence to recommended treatment and monitoring of prescriptions and dose.9 10 Patients can be informed about what to expect from treatment and be motivated to report adverse events or complications and keep a list of their medical histories, allergies and current medications.11

Patients’ direct experience of care process through clinical encounters or as an observer (eg, as a patient on a hospital ward) can provide valuable insights into everyday care. Examples include attention to pain control, assistance with bathing or help with feeding, the environment (cleanliness, noise and physical safety) and coordination of care between professions or organisations. Given the organisational fragmentation of much of healthcare and the numerous services with which many patients interact, the measurement of patient experience may help provide a ‘whole-system’ perspective not readily available from more discrete patient safety and clinical effectiveness measures.11

Focusing on such utilitarian arguments, this study reviews evidence on links that have been demonstrated between patient experience and clinical effectiveness and patient safety.

Methods

Identifying variables relevant to patient experience

Patient experience is a term that encapsulates a number of dimensions, and in preliminary database searches, this phrase, on its own, uncovered a limited number of useful studies. To broaden and structure the search for evidence, identify search terms and provide a framework for analysis, it was necessary to identify what patient experience entails and outline potential mechanisms through which it is proposed to impact on safety and effectiveness. As such, we combined common elements from patient experience frameworks produced by The Institute of Medicine,1 Picker Institute12 and NICE.13

Table 1 delineates different dimensions of patient experience and distinguishes between ‘relational’ and ‘functional’ aspects.10 14 Relational aspects refer to interpersonal aspects of care—the ability of clinicians to empathise, respect the preferences of patients, include them in decision-making and provide information to enable self-care.10 It also refers to patients’ expectations that professionals will put their interest above other considerations and be honest and transparent when something goes wrong.8 15 Functional aspects relate to basic expectations about how care is delivered, such as attention to physical needs, timeliness of care, clean and safe environments, effective coordination between professionals, and continuity.

Table 1.

Identifying aspects of patient experience and search terms

| Relational aspects | Functional aspects |

|---|---|

| Emotional and psychological support, relieving fear and anxiety, treated with respect, kindness, dignity, compassion, understanding | Effective treatment delivered by trusted professionals |

| Participation of patient in decisions and respect and understanding for beliefs, values, concerns, preferences and their understanding of their condition | Timely, tailored and expert management of physical symptoms |

| Involvement of, and support for family and carers in decisions | Attention to physical support needs and environmental needs (eg, clean, safe, comfortable environment) |

| Clear, comprehensible information and communication tailored to patient needs to support informed decisions (awareness of available options, risks and benefits of treatments) and enable self-care | Coordination and continuity of care; smooth transitions from one setting to another |

| Transparency, honesty, disclosure when something goes wrong |

Using these frameworks and discursive documents in this area of research9 10 16 17 as a guide, we identified words and phrases commonly used to denote aspects of patient experience, examples of which are listed in box 1.

Box 1. Search terms denoting patient experience.

Patient-centred care; patient engagement; clinical interaction; patient–clinician; clinician–patient; patient–doctor; doctor–patient; physician–patient; patient–physician; patient–provider; interpersonal treatment; physician discussion; trust in physician; empathy; compassion; respect; responsiveness; patient preferences; shared decision-making; therapeutic alliance; participation in decisions; decision-making; autonomy; caring; kindness; dignity; honesty; participation; right to decide; physical comfort; involvement (of family, carers, friends); emotional support; continuity (of care); smooth transition; emotional support.

These were combined with search terms representing patient safety and clinical effectiveness outcomes, hypothesised to be associated with patient experience in discursive literature. We searched for a broad range of outcome measures, including both self-rated and ‘objective’ measurements of health status, physical health and mental health and well-being, the use of preventive health services, compliance or adherence to health-promoting behaviour and resource use.

Combining these two sets of search terms in the EMBASE database, we identified 5323 papers whose abstracts were then reviewed. If deemed relevant, the full article was retrieved to assess whether it met the inclusion criteria.

Given concerns about the sole use of protocol-driven search strategies for complex evidence,18 for the full-text articles retrieved for review, we used a ‘snowballing’ approach to identify further studies. This involved sourcing further articles in these studies for assessment and using the ‘related articles’ function in the Pubmed database. We repeated this for new articles identified until the approach ceased to identify new studies.

Inclusion criteria, assessment of quality and categorisation of evidence

We included studies that measured associations between patients’ reporting of their experience and patient safety and clinical effectiveness outcomes. These included studies measuring associations between patient experience and safety or effectiveness outcomes either at a patient level (ie, data on both types of variables for the same patients) or at an organisational level (ie, associations between aggregated measures of patient experience and safety and effectiveness outcomes for the same type of organisation such as a hospital or primary-care practice).

We included studies where the variables denoting patient experience and patient safety and clinical effectiveness were measured in a credible way, through the use of validated tools. For patient experience variables, these include surveys covering several aspects of experience (such as Picker surveys and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey) and specific aspects (such as a ‘Working Alliance Scale’,19 Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale scale20 or Usual Provider Continuity index21). For patient safety and clinical effectiveness, these include, for example, generic health and quality of life surveys (such as Short-Form 36), disease-specific surveys (such as the Seattle Angina Questionnaire22), measures of the technical quality of care (such as the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA) score), reviews of medical records and care provider data.23 Details of the methods used to measure variables in each study are included in tables 5 and 6.

Table 5.

Individual studies

| Author | Type of study, sample size, country | Setting | Disease focus | Unit of analysis (patient (P) or org (O) | Patient experience focus and method used | Safety and effectiveness measure | Association demonstrated | Association not demonstrated | Assoc. Found vs NOT found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al48 | Cohort study, 236 patients, USA | Managed care organisation | 22 clinical conditions | P | Providers communication (The Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey and ‘Quality of care’) | Technical quality and patient global ratings (medical records and patient interviews) | None | Technical quality of care | 0/1 |

| Sequist et al24 | Cross-sectional study, 492 settings, USA | Primary care | Cervical, breast and colorectal cancer, chlamydia, cardiovascular conditions, asthma, diabetes | P | Doctor–patient communication, clinical team interactions, organisational features of care (The Ambulatory Care Experiences survey) | Clinical quality focusing on disease prevention, disease management and outcomes of care (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS)) | Cervical cancer, breast cancer and colorectal cancer screening, Chlamydia screening, Cholesterol screening (cardiac), LDL cholesterol testing (diabetes), eye exams (diabetes), HbA1c testing, nephropathy screening | Cholesterol management, HbA1c control, LDL cholesterol control, blood pressure control | 9/4 |

| Burgers et al55 | Survey, 8973 patients, Range | Range of settings | Chronic lung, mental health, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, arthritis, cancer | P | Coordination of care and overall experience (Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey) | Death score | Death score | None | 1/0 |

| Kaplan et al25 | Randomised control trial, 252 patients, USA | Range of settings | Ulcer disease, hypertension, diabetes, breast cancer | P | Physician–patient communication (assessment of audio tape and questionnaire) | Physiological measures taken at visit and patients’ self-rated health status survey. | Follow-up blood glucose and blood pressure, functional health status, self-reported health status. | None | 4/0 |

| Jha et al23 | Cross-sectional study, 2429 settings, USA | Hospital | Acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia complications from surgery | O | Patient communication with clinicians, experience of nursing services, discharge planning (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey) | Technical quality of care using Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA) score | Technical quality of care in AMI, congestive heart failure (CHF), pneumonia, surgical care | None | 4/0 |

| Rao et al47 | Cross-sectional study, 3487 patients, UK | Primary care | Hypertension, Influenza vaccination | P | Older patients’ experience of technical quality of care (General Practice Assessment survey) | Technical quality of care—(medical records) | None | Hypertension monitoring and control, influenza vaccination. | 0/3 |

| Meterko et al26 | Cohort study, 1858 patients, USA | Veteran Affairs Medical Centres | Acute myocardial infarction | P | Patient-centred care, access, courtesy, information, coordination, patient preferences, emotional support, family involvement, physical comfort (VA Survey of Healthcare Experiences of Patients (SHEP)) | Survival 1-year postdischarge | Survival 1-year post discharge | None | 1/0 |

| Vincent et al56 | Cohort survey 227 patients, UK | Range of settings | Varied | P | Accountability, explanation, standards of care, compensation (questionnaire) | Legal action | Legal action | None | 1/0 |

| Agoritsas et al57 | Cohort patient survey, 1518 patients, Switzerland | Hospital | Varied | P | Global rating of care and respect and dignity questions (Picker survey) | Patient reports of undesirable events (survey) | Neglect of important information by healthcare staff, pain control, needless repetition of a test, being handled with roughness | None | 4/0 |

| Flocke et al37 | Cross-sectional study, 2889 patients, USA | Primary care | Varied | P | Interpersonal communication, physician's knowledge of patient, coordination (Components of Primary Care Instrument (CPCI)) | Use of preventive care services (screening, health habit counselling services, immunisation services) | Screening, health habit counselling, immunisation | None | 3/0 |

| Jackson, J. et al58 | Quantitative cohort study 500 patients, USA | General medicine walk-in clinic | Varied | P | Patient satisfaction (Research and Development (RAND) 9-item survey) | Functional status (Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-6)), symptom resolution, (RAND 9-item survey), follow-up visits | Symptom resolution, repeat visits, functional status | None | 3/0 |

| Clark et al41 | Randomised control trial 731 patients, USA | Range of settings | Asthma | P | Patient experience of physician communication (patient interviews and Likert scale) | Emergency department visits, hospitalisations, office phone calls and visits, urgent office visits (survey+medical chart review of 6% of patients to verify responses) | Number of office visits, emergency visits, urgent office visits, phone calls, hospitalisations | None | 5/0 |

| Raiz et al20 | Quantitative cohort study, 357 patients, USA | Primary care | Renal transplant | P | Patient faith in doctor (Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale (MHLC)) | Medication compliance | Remembering medications, taking medications as prescribed | None | 2/0 |

| Kahn et al32 | Cohort study, 881 patients, USA | Hospitals | Breast cancer | P | Level of physician support, participation in decision-making and information on side effects (survey) | Medication adherence | Ongoing tamoxifen use | None | 1/0 |

| Plomondon et al22 | Cohort study, 1815 patients, USA | Hospital | Myocardial infarction | P | Satisfaction with explanations from their doctor, overall satisfaction with treatment (Seattle Angina questionnaire) | Presence of angina (Seattle Angina Questionnaire) | Presence of angina | None | 1/0 |

| Fuertes et al19 | Survey, 152 patients, USA | Hospital | Neurology | P | Physician–patient communication, physician–patient working alliance, empathy, multicultural competence (questionnaire) | Adherence to medical treatment (adherence Self-Efficacy Scale and Medical Outcome Study (MOS) adherence scale) | Adherence to treatment | None | 1/0 |

| Lewis et al31 | Qualitative cohort study, 191 patients, USA | Primary care | Pain | P | Doctor–patient communication (survey) | Medication adherence (Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ)) | Use of prescribed opioid medications | None | 1/0 |

| Safran et al59 | Cross-sectional study, 7204 patients, USA | Primary care | Varied | P | Accessibility, continuity, integration, clinical interaction, interpersonal aspects, trust (The Primary Care Assessment Survey) | Adherence to physician's advice, health status, health outcomes (Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), Behavioural risk factor survey) | Adherence, health status | Health outcomes | 2/1 |

| Alamo et al60 | Randomised study, 81, Spain | Primary care | Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP), fibromyalgia | P | Patient-centreed-care (‘Gatha-Res questionnaire’ and follow-up phone call) | Pain (Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) anxiety (Oldberg scale of anxiety and depression (GHQ)) | Anxiety, number of tender points (pain) | Pain, pain intensity, pain as a problem, number of associated symptoms, depression, physical mobility, social isolation, emotional reaction, sleep | 2/10 |

| Fan et al61 | Survey, 21 689 patients, USA | Primary care | Cardiac care, diabetes, congestive obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) | P | Communication skills and humanistic qualities of primary care physician (Seattle Outpatient Satisfaction Survey) | Physical and emotional aspects, coping ability and symptom burden for angina, COPD and diabetes (Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ), Obstructive Lung Disease Questionnaire (SOLDQ), Diabetes Questionnaire (SDQ)) | Patient ability to deal with all 3 diseases, education for diabetes patients, angina stability, physical limitation due to angina | Self-reported physical limitation for angina and COPD, symptom burden for diabetes, complications for diabetes | 7/4 |

| O'Malley et al38 | Cross-sectional study, 961 patients, USA | Primary care | Varied | P | Patient trust (survey) | Use of preventive care services | Blood pressure measurement, height and weight measurement, cholesterol check, papanicolaou test (pap) tests, breast cancer screening, colorectal cancer screening, discussion of diet, discussion on depression | None | 8/0 |

| Little et al62 | Survey, 865 patients, UK | Primary care | varied | P | Patient centredness (Survey) | Enablement, symptom burden, resource use | Enablement, symptom burden, referrals | Re-attendance, investigations | 3/2 |

| Levinson et al63 | Qualitative cohort study, 124 physicians, USA | Primary care | Varied | P | Physician–patient communication (assessment of audiotape) | Malpractice | Malpractice claims | None | 1/0 |

| Carcaise-Edinboro and Bradley39 | Cross sectional study, 8488 patients, USA | Primary care | Colorectal cancer | P | Patient-provider communication (Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey) | Colorectal Cancer screening, fecal occult blood testing and colonoscopy (Medical Expenditure Panel Survey) | CRC screening, fecal occult blood testing, colonoscopy | None | 3/0 |

| Schneider et al33 | Cross-sectional analysis study, 554 patients, USA | Primary care | HIV | P | Physician–patient relationship (survey) | Adherence (survey) | Adherence to antiretroviral therapy | None | 1/0 |

| Schoenthaler et al34 | Cross-sectional study, 439 patients, USA | Primary care | Hypertension | P | Patients’ perceptions of providers’ communication (survey) | Medication adherence (Morisky self-report measure) | Medication adherence | None | 1/0 |

| Slatore et al64 | Cross-sectional study, 342 patients, USA | Range of settings | COPD | P | Patient–clinician communication (Quality of communication questionnaire (QOC)) | Self-reported breathing problem confidence and general self-rated health (survey) | Confidence in dealing with breathing problems | Self-rated health | 1/1 |

| Lee and Lin65 | Cohort study, 480 patients, Taiwan | Range of settings | Type 2 diabetes | P | Trust in physicians (survey) | Self-efficacy, adherence, health outcomes (Multidimensional Diabetes Questionnaire and 12-Item Short-Form Health survey (SF-12)) | Physical HRQoL, mental HRQoL, body mass index HbA1c, triglycerides, complications, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, adherence | None | 9/0 |

| Heisler et al35 | Survey, 1314 patients, USA | Primary care | Diabetes | P | Physician communication, physician interaction styles, participatory decision-making (Questionnaire) | Disease management (surveys and national databases) | Overall self-management, diabetes diet, medication compliance, exercise, blood glucose monitoring, foot care. | Exercise | 6/1 |

| Lee and Lin66 | Cohort study, 614 patients, Taiwan | Range of settings | Type 2 diabetes | P | Patients’ perceptions of support, autonomy, trust, satisfaction (Healthcare Climate Questionnaire and Autonomy Preference Index (API)) | Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1C) (medical records) Physical and mental health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (SF-12) | Physical HRQoL, mental HRQoL | Information preference interaction, HbA1C | 2/2 |

| Kennedy A. et al67 | Randomised control trial, 700 patients, UK | Hospital | Inflammatory bowel Disease | P | Patient-centred-care (interviews) | Resource use, self-rated physical and mental health, enablement (patient diaries, questionnaires, medical records) | Ability to cope with condition, symptom relapses, hospital visits, appointments made | Physical functioning, role limitations, social functioning, mental health, energy/vitality, pain, general health perception, anxiety, number of relapses, number of medically-defined relapses, average relapse duration, frequency of GP visits, delay before starting treatment | 4/13 |

| Stewart et al42 | Observational cohort study, 315 patients, Canada | Primary care | General | P | Patient-centred communication (assessment of audiotape and Patient-Centred Communication Score tool) | Discomfort (VAS) symptom severity severity (Visual Analogue Scale), Health Status (Short Form-36 SF-36) Quality of care provision (chart review by doctors) | Symptom discomfort and concern, self-reported health, diagnostic tests, referrals and visits to the family physician | None | 5/2 |

| Kinnersley et al68 | Observational study, 143 patients, UK | Primary care | Varied | P | Patient-centredness (assessment of audiotape and questionnaires) | Symptom resolution, resolution of concerns, functional health status (Questionnaire) | None | Resolution of symptoms, resolution of concerns, functional health status | 0/3 |

| Solberg et al51 | Survey, 3109 patients, USA | Primary care—multispecialty group | Varied | P | Patient experience of errors (survey) | Review of errors (chart audits and physician reviewer judgements) | None | None | 1/0 |

| Isaac et al6 | Cross-sectional study, 927 hospitals, USA | Hospital | Acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia complications from surgery. | O | General patient experiences (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey (HCAHPS)) | Processes of care (Health Quality Alliance (HQA) database) and patient safety indicators | Decubitus ulcer rates, infections, processes of care for pneumonia, CHF and myocardial infarctions, surgical composites, hemorrage, respiratory failure, DVT, pulmonary embolism, sepsis | Failure to rescue | 11/1 |

| Glickman et al27 | Cohort study, 3562 patients, USA | Hospital | Acute myocardial infarction | P | Patient satisfaction (Press-Ganey survey) | Adherence to practice guidelines, outcomes (CRUSADE quality improvement registry). | Inpatient mortality, composite clinical measures, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) survival | None | 3/0 |

| Fremont et al69 | Survey, 1346 patients, USA | Hospital | Cardiac | P | Patient-centred care (Picker survey) | Processes of care, functional health status, cardiac symptoms (Medical Outcomes Study questionnaire, London School of Hygiene measures for cardiac symptoms) | Overall health, chest pain, patient reported general physical and mental health status | Mental health, shortness of breath | 5/2 |

| Riley et al70 | Survey, 506 patients, Canada | Hospital | Cardiac care—acute coronary | P | Continuity of care (The Heart Continuity of Care Questionnaire, Medical Outcome Study Social Support Survey, Illness Perception Questionnaire) | Participation in cardiac rehabilitation, perception of illness, functional capacity (Duke Activity Status Index (DASI)) | Cardiac rehabilitation participation, perceptions of illness consequences | None | 2/0 |

| Weingart et al49 | Cohort study, 228 patients, USA | Hospital | Varied | P | Patient experience of adverse events (interviews) | Adverse events (mMedical records and patient interviews) | Adverse events | None | 1/0 |

| Weissman et al50 | Survey, 998 patients, USA | Hospital | Varied | P | Patient experience of adverse events (interviews) | Adverse events (medical records) | Adverse events | None | 1/0 |

HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Table 6.

Systematic reviews

| Authors | Time span and studies meeting inclusion criteria | Healthcare setting | Disease areas covered | Unit of analysis | Patient experience focus (and measurement methods) | Safety and effectiveness measure—association demonstrated - | Safety and effectiveness measure—association not demonstrated | Assocs found vs not found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blasi et al71 | 1974–1998, 4 of 25 | Range of settings | Asthma, hypertension, cancer, insomnia, menopause, obesity, tonsillitis | P | Provider behaviour and communication (grading of consultations) | Health status, symptom improvement, treatment effectiveness, fear of injection, anxiety, ratings of pain, number of doctor visits, pain, speed of recovery | Comfort, recovery time, return visits | 9/3 |

| Drotar29 | 1998–2008, 4 of 22 | Range of settings | Asthma, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, epilepsy, inflammatory bowel disease, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis | P | Physician and staff behaviour (surveys, interviews, medical records) | Treatment adherence, compliance, office visits, phone calls, hospitalisations | Medication adherence | 5/1 |

| Hall et al72 | 1990–2009, 10 of 14 | Range of settings | Brain injury, musculoskeletal conditions, cardiac conditions, trauma, back, neck and shoulder pain | P | Therapist-patient relationship, therapeutic alliance (surveys, audio/video taped session) | Adherence, employment status, physical training, therapeutic success, perceived effect of treatment, pain, physical function, depression, general health status, attendance, floor-bench lifts, global assessment scores, ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), mobility | Weekly physical training, disability, productivity, depression, functional status, adherence | 18/6 |

| Stevenson et al73 | 1991–2000, 7 of 134 | Range of settings | Hypertension, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, ovarian cancer, epilepsy, hyperlipidaemia | P | Doctor–patient communication (surveys) | Self-reported adherence, blood pressure control, general physician practice visits, hospitalisations, emergency room visits for children with asthma, quality of life for COPD patients, oral contraceptive adherence, adherence to antiepileptic drugs, pain control following gynaecological surgery, adherence to medication for depression | Length of visits to doctor for asthma patients, health status and use of healthcare services for epilepsy patients, adherence to Niacin and bile acid sequestrant therapy | 9/5 |

| Saultz and Lochner44 | 1967–2002, 41 studies | Range of settings | Varied | P | Continuity of care —ongoing relationship between individual doctor and patient (surveys, continuity of care index) | Hospitalisation rate, hospital readmission, length of stay, influenza immunisation, preventive care, antibiotic compliance, intensive care unit days, Neonatal morbidity, Apgar score, Birth weight, rates and timeliness of childhood immunisations, health-related quality of life, recommended diabetes care measures, glucose control, PAP tests, mammogram rate, breast exams, surgical operation rates, hypertension control, presence of depression, relationship problems, adverse events in hospitalsed patients, degree of patient enablement, rheumatic fever incidence | Diabetes (HbA1C, lipid control, blood pressure control, presence of diabetic complications), blood glucose control, functional ability of elderly patients, compliance with antibiotic therapy, well-child visits, blood pressure checks in women, pregnancy complications, newborn mortality, immunization rates, NICU admissions, Apgar scores, caesarean rate, length of labour, indications for tonsillectomy | 51/30 |

| Hall, Roter and Katz74 | Meta-analysis 41 studies | Range of settings | Varied | P | Clinician–patient communication (surveys, interviews, observations, assessment of video or audio) | Compliance (with 4 variables of PE), recall/understanding (with 4 variables of PE) | Compliance (with 1 variable of PE), recall/understanding (with 1 variable of PE) | 8/2 |

| Jackson, C. et al 40 | 1984–2008, 3 of 17 | Range of settings | Inflammatory bowel disease | P | Trust in physician, Patient–physician agreement, adequacy information (surveys) | Adherence to treatment | Compliance | 2/1 |

| Sans-Coralles et al43 | 1984–2005, 9 of 20 | Primary care | No specific disease focus | P | Continuity of care, coordination of care, consultation time, doctor–patient relationship (validated tools in these different domains) | Hospital admissions, length of stay, compliance, recovery from discomfort, emotional health, diagnostic tests, referrals, quality of care for asthma, diabetes and angina, symptom burden, receipt of preventive services | Enablement | 13/1 |

| Hsiao and Boult45 | 1984–2003, 3 of 14 | Primary care | No specific disease focus | P | Continuity with physician (surveys, interviews, medical records, chart reviews) | Hospitalisations for all conditions and ambulatory care-sensitive conditions, odds of hospitalisation(2), healthcare costs(2), emergency department visits, emergent hospital admissions(2), length of stay, diabetes recognition, mental health(2), pain, perception of health, well-being, BMI, triglyceride concentrations, recovery, clinical outcomes, self-reported health | Acute ambulatory care-sensitive conditions, mobility, pain, emotion, activities of daily living, smoking, BMI, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, self-reported health, glycaemic control, diabetes control, frequency of hypoglycaemic reactions, blood sugar, weight | 21/15 |

| Arbuthnott et al30 | Meta analysis, 1955–2007, All 48 studies included | Range of settings | Asthma, bacterial infection, flbromyalgia, diabetes, renal disease, hypertension, congestive heart failure, inflammatory bowel disease, breast cancer, HIV and tuberculosis | P | Physician–patient collaboration (Observation, surveys) | Medication adherence, behavioural adherence | Appointment adherence | 2/1 |

| Stewart75 | 1983–1993, 21 studies | Range of settings | Peptic ulcers, breast cancer, diabetes, hypertension, headache, coronary artery disease, gingivitis, tuberculosis, prostate cancer | P | Physician–patient communication (surveys, evaluation of audio- or videotape recording) | Peptic ulcer physical limitation, blood glucose levels, blood pressure, headache resolution, physician evaluation of symptom resolution for coronary artery disease, gingivitis and tuberculosis, anxiety level in gynaecological care, radiation therapy, breast cancer care, functional status following radiation therapy for prostate cancer, anxiety after radiation therapy, pain levels and hospital length of stay after intra-abdominal surgery, physical and psychological complaints in breast cancer care | Details not included | 16/5 |

| Zolnierek and DiMatteo28 | Meta analysis 1949–2008, 127 studies | Range of settings | No specific disease focus | P | Physician–patient communication (observation, surveys) | Adherence to treatment recommended by clinician | Adherence (2 observational studies) | 125/2 |

| Beck et al76 | 1975–2000, 5 of 14 | Primary care | No specific disease focus | P | Physician–patient communication (observation, evaluation of audio and video tapes) | Compliance with doctors’ advice, blood pressure, pill count | None | 10/0 |

| Cabana and Lee21 | 1966–2002, 7 of 18 | Range of settings | Rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy, breast cancer, cervical cancer, diabetes | P | Continuity of care (validated measures of continuity eg, SCOC) | Hospitalisations, length of stay, emergency department visits, intensive care days, preventive medicine visits, drug or alcohol abuse, outpatient attendance, glucose control for adults with diabetes | None | 18/5 |

| Richards et al77 | 1997–2002, 2 of 33 | Range of settings | Psoriasis | P | Patient's perception of care, satisfaction, interpersonal skills (surveys, interviews) | Treatment adherence, medication use | None | 2/0 |

BMI, body mass index.

We included studies where the sample size of patients or organisations appeared sufficiently large to conduct a meaningful statistical analysis (excluding studies with fewer than 50 subjects). When extracting data relevant to our study from systematic reviews, we selected only those studies that met these criteria.

We then searched the studies’ results for positive associations (where a better patient experience is associated with safer or more effective care), negative associations (where a better patient experience is associated with less safe or less effective care) and no associations. Associations refer to cases where one measure of patient experience (typically an overall rating of patient experience for a care provider) has a statistically significant association with one or more clinical effectiveness or patient safety variable. If a study showed associations between several aspects of patient experience that appeared to be closely related (eg, ‘listening’, ‘empathy’, or ‘respect’) and an aspect of effectiveness or safety, this was counted as one association found. This was to avoid exaggerating the weight of the evidence by ‘over counting’ associations.

Two main types of studies emerged in the search—those focusing on interventions to improve aspects of patient experience and those exploring associations between patient experience variables and patient safety and clinical effectiveness variables. To manage the scope of this time-limited review, we decided to restrict analysis of the large number of interventions to the evidence contained within systematic reviews.

Results

Overall, the evidence indicates positive associations between patient experience and patient safety and clinical effectiveness that appear consistent across a range of disease areas, study designs, settings, population groups and outcome measures. Positive associations found outweigh ‘no associations’ by 429–127. Of the four studies where ‘no associations’ outweigh positive associations, there is no suggestion that these are methodologically superior. Negative associations were rare. Of the 40 individual studies assessed in table 5 negative associations (between patient experience of clinical team interactions and continuity of care and separate assessment of the quality of clinical care) were found in only one study.24

Table 2 shows surveys to be the predominant method used to measure variables for individual studies (figure 1).

Table 2.

Methods used to measure variables

| Number of studies | |

|---|---|

| Patient experience variables | |

| Survey | 31 |

| Interviews | 2 |

| Medical records | 1 |

| Effectiveness and safety variables | |

| Survey for self-rated healthcare | 12 |

| Other survey | 14 |

| Medical records | 3 |

| Data-monitoring quality of care delivery (eg, audit, HQA, HEDIS) | 3 |

| Care provider outcome data | 3 |

| Physical examination | 1 |

| Patient interviews | 2 |

HQA, Hospital Quality Alliance; HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set.

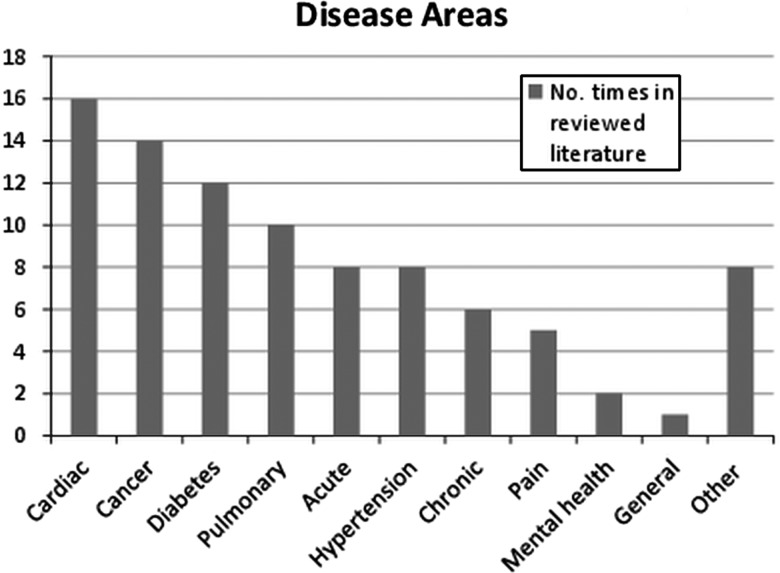

Figure 1.

Outlines the disease areas covered.

Table 3 presents the frequency of positive associations and ‘no associations’ categorised by type of outcomes (for 378 of the 556 cases where sufficient information was available to categorise). These include objectively measured health outcomes (eg, ‘mortality’, ‘blood glucose levels’, ‘infections’, ‘medical errors’); self-reported health and well-being outcomes (eg, ‘health status’, ‘functional ability’ ‘quality of life’, ‘anxiety’); adherence to recommended treatment and use of preventive care services likely to improve health outcomes (eg, ‘medication compliance’, ‘adherence to treatment’ and screening for a variety of conditions); outcomes related to healthcare resource use (eg, ‘hospitalisations’, ‘hospital readmission’, ‘emergency department use’, ‘primary care visits’); errors or adverse events and measures of the technical quality of care.

Table 3.

Associations categorised by type of outcome

| Objective’ health outcomes | Self-reported health and wellbeing | Adherence to treatment (including medication) | Preventive care | Healthcare resource use | Adverse events | Technical quality of care | All categories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of positive associations found | 29 | 61 | 152 | 24 | 31 | 7 | 8 | 312 |

| ‘No associations’ | 11 | 36 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 66 |

Table 4 shows associations categorised by type of care provider (for the subset of studies focusing on one setting) and for studies focused on chronic conditions.

Table 4.

Weight of evidence by provider and for chronic conditions

| Weight of evidence by provider and for chronic conditions | Associations found | No of associations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary care | 110 | 48 |

| Hospital | 43 | 17 |

| Chronic conditions | 53 | 9 |

Tables 5 and 6 present details of all studies identified, specifying the analytical focus of each study, methods to measure variables and positive associations and ‘no asscoiations’ found.

Discussion

Overall, the evidence indicates associations between patient experience, clinical effectiveness and patient safety that appear consistent across a range of disease areas, study designs and settings.

As table 3 indicates, the evidence shows positive associations found outweigh those not found for both self-assessment of physical health and mental health (61 vs 36) and ‘objective’ measures of health outcomes (eg, where measures are taken by a clinician or by reviewing medical records) (29 vs 11). For objective measures, one study25 shows positive associations for ulcer disease, hypertension and breast cancer. Two studies on myocardial infarction show positive associations with survival 1 year after discharge26 and inpatient mortality.27 Objective measurement is less frequently explored than self-rated health and is an area that could benefit from further research.

Evidence is strong in the case of adherence to recommended medical treatment. A meta-analysis included in this study showed positive associations between the quality of clinician–patient communications and adherence to medical treatment in 125 of 127 studies analysed and showed the odds of patient adherence was 1.62 times higher where physicians had communication training.28 Regarding compliance with medication, positive associations found to outweigh those not found.20 29–35 A review of interventions to increase adherence to medication (not included in this study) showed communication of information, good provider–patient relationships and patients’ agreement with the need for treatment as common determinants of effectiveness.36 There is evidence of better use of preventive services, such as screening services in diabetes, colorectal, breast and cervical cancer; cholesterol testing and immunisation.24 25 37–39 There is also evidence of impacts on resource use of primary and secondary care (such as hospitalisations, readmissions and primary care visits).21 29 40–45

For studies exploring associations between patient experience and technical quality of care measured by other means, the evidence is mixed. Two studies in acute care showed positive associations between overall ratings of patient experience and ratings of the technical quality of care (using HQA measures) for myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia and complications from surgery.23 46 Another found an association with adherence to clinical guidelines for acute myocardial infarction.27 A similar study in primary care found positive associations between patient experience of processes and measurement of care quality (from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) system measuring care quality for disease prevention and management in chronic conditions).24 However, two other studies found no associations between patients’ ratings and ratings based on an assessment of medical records.47 48

Some studies show positive associations between patients’ perspective or observations of processes of care and the safety of care recorded through other means. Isaac46 found positive associations between ratings of patient experience and six patient-safety indicators (decubitus ulcer; failure to rescue; infections due to medical care; postoperative haemorrhage, respiratory failure, pulmonary embolism and sepsis). Two studies examining evidence for patients’ ability to identify medical errors or adverse events in hospital showed positive associations between patients’ accounts of their experience of adverse events and the documentation of events in medical records.49 50 But another study shows only 2% of patient-reported errors were classified by medical reviewers as ‘real clinical medical errors’ with most ‘reclassified’ by clinicians as ‘misunderstandings’ or ‘behaviour or communication problems’.51 Overall, there is less evidence available on safety compared to effectiveness and this should be a priority for future research in this area.

Research from other studies not included in this review support these findings. For example, research on ‘decision aids’ to ensure that patients are well informed about their treatments, and that decisions reflect the preferences of patients indicates that patient engagement has a beneficial impact on outcomes. For example, awareness of the risks of surgical procedures resulted in a 23% reduction in surgical interventions and better functional status.52 Another review showed that provision of good information and emotional support are associated with better recovery from surgery and heart attacks.53

Study strengths and limitations

This review builds on other studies9 10 16 17 exploring links between these three domains. This study also demonstrates an approach to designing a systematic search for evidence for the ‘catch-all’ term patient experience, bringing together evidence from a variety of sources that may otherwise remain dispersed. This approach can be used or adapted for further research in this area.

This was a time-limited review and there is scope to expand this search, based on our results. There may be scope to broaden the search terms and this may uncover further evidence. The first search was confined to one database and the review focused primarily on peer-reviewed literature excluding grey literature. To manage the scope of this review, we restricted the analysis of interventions to improve patient experience to evidence within systematic reviews. While we used some quality criteria to filter studies (including the use of validated tools to measure experience, safety and effectiveness outcomes and sample size), with more time a more detailed formal quality assessment may have added value to the study. Although all positive associations included in the study are statistically significant, the strength of associations vary. Because of time constraints and the heterogeneity of measures used, we did not systematically compare the strengths of positive associations in different studies, but this may be an area for future work. There may also be scope to explore whether future research in this area could go beyond the counting of associations in this study through, for example, meta-analysis. As always, there may be a publication bias in favour of studies showing positive associations between patient experience variables and safety and effectiveness outcomes.54 In addition, 28 of the 40 individual studies assessed were conducted in the USA and caution is needed about their applicability to other healthcare systems.

Conclusion

The inclusion of patient experience as one of the pillars of quality is partly justified on the grounds that patient experience data, robustly collected and analysed, may help highlight strengths and weaknesses in effectiveness and safety and that focusing on improving patient experience will increase the likelihood of improvements in the other two domains.3

The evidence collated in this study demonstrates positive associations between patient experience and the other two domains of quality. Because associations do not entail causality, this does not necessarily prove that improvements in patient experience will cause improvements in the other two domains. However, the weight of evidence across different areas of healthcare indicates that patient experience is clinically important. There is also some evidence to suggest that patients can be used as partners in identifying poor and unsafe practice and help enhance effectiveness and safety. This supports the argument that the three dimensions of quality should be looked at as a group and not in isolation. Clinicians should resist sidelining patient experience measures as too subjective or mood-orientated, divorced from the ‘real’ clinical work of measuring and delivering patient safety and clinical effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work thank Mandy Wearne at NHS Northwest who commissioned this work and provided comments on earlier drafts, We are also grateful to Jocelyn Cornwell who provided comments on an early draft of this article. This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) programme for North West London. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors: CD and DB conceived of the study and were responsible for the design and search strategy. CD and LL were responsible for conducting the search. CD and LL conducted the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. Derek Bell provided input into the data analysis and interpretation. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by CD then circulated among all authors for critical revision. All authors helped to evolve analysis plans, interpret data and critically revise successive drafts of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black N, Jenkinson C. Measuring patients experiences and outcomes. BMJ 2009;339:202–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health Liberating the NHS:transparency in outcomes—a framework for the NHS: Department of Health, 2010

- 4.Darzi A. High quality care for all—NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. Department of Health, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health Using the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) payment framework, 2008

- 6.Berwick DM. What ‘patient-centered’ should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff 2009;28:w555–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Street RL, Makoul G, Arora NK, et al. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Ed Couns 2009;74:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thom DH, Hall MA, Pawlson LG. Measuring patients’ trust in physicians when assessing quality of care. Health Aff 2004;23:124–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:76–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulter A. Engaging patients in healthcare. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rathert C, Huddleston N, Pak Y. Acute care patients discuss the patient role in patient safety. Health Care Manag Rev 2011;36:134–44 10.1097/HMR.0b013e318208cd31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picker Institute Patient experience surveys: the rationale Picker Institute Europe, Oxford, 2008

- 13.NICE Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services. Manchester: NICE, 2011

- 14.Iles V, Vaughan Smith J. Working in health care could be one of the most satisfying jobs in the world—why doesn't it feel like that?, 2009

- 15.López L, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, et al. Disclosure of hospital adverse events and its association with patients’ ratings of the quality of care. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1888–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, et al. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract 1998;47:213–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Good for Health, good for business: the case for measuring patient experience of care: The Center for Health Care Quality at the George Washington University Medical Center, Washington DC.

- 18.Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ 2005;331:1064–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuertes J, Boylan L, Fontanella J. Behavioral indices in medical care outcome: the working alliance, Adherence, and related factors. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:80–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raiz LR, Kilty KM, Henry ML, et al. Medication compliance following renal transplantation. Transplantation 1999;68:51–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabana M, Jee S. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J Fam Pract 2004;53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plomondon M, Magid D, Masoudi F, et al. Association between angina and treatment satisfaction after myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, et al. Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1921–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sequist , et al. Quality Monitoring of Physicians: Linking Patients’ Experiences of Care to Clinical Quality and Outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care 1989;27(3 Suppl):S110–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meterko M, Wright S, Lin H, et al. Mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the influences of patient-centered care and evidence-based medicine. Health Serv Res 2010;45(5p1):1188–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:188–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zolnierek HKB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2009;47:826–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drotar D. Physician behavior in the care of pediatric chronic illness: association with health outcomes and treatment adherence. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009;30:246–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arbuthnott A, Sharpe D. The effect of physician-patient collaboration on patient adherence in non-psychiatric medicine. Patient Ed Couns 2009;77:60–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis ET, Combs A, Trafton JA. Reasons for under-use of prescribed opioid medications by patients in pain. Pain Med 2010;11:861–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahn KL, Schneider EC, Malin JL, et al. Patient centered experiences in breast cancer: predicting long-term adherence to tamoxifen use. Med Care 2007;45:431–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE, et al. National quality monitoring of medicare health plans: the relationship between enrollees’ reports and the quality of clinical care. Med Care 2001;39:1313–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoenthaler A, Chaplin WF, Allegrante JP, et al. Provider communication effects medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Patient Ed Couns 2009;75:185–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, et al. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:243–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flocke SA, Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ. The association of attributes of primary care with the delivery of clinical preventive services. Med Care 1998;36:AS21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, et al. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med 2004;38:777–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carcaise-Edinboro P, Bradley CJ. Influence of patient-provider communication on colorectal cancer screening. Med Care 2008;46:738–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, et al. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:525–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark NM, Cabana MD, Nan B, et al. The clinician-patient partnership paradigm: outcomes associated with physician communication behavior. Clin Pediatr 2008;47:49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart M, Brown J, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 2000;49:796–804 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sans-Corrales M, Pujol-Ribera E, Gené-Badia J, et al. Family medicine attributes related to satisfaction, health and costs. Fam Pract 2006;23:308–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:159–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsiao C-J, Boult C. Effects of quality on outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. A J Med Qual 2008;23:302–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isaac T, Zaslavsky AM, Cleary PD, et al. The relationship between patients’ perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv Res 2010;45:1024–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao M, Clarke A, Sanderson C, et al. Patients’ own assessments of quality of primary care compared with objective records based measures of technical quality of care: cross sectional study. BMJ 2006;333:19–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang JT, Hays RD, Shekelle PG, et al. Patients’ global ratings of their health care are not associated with the technical quality of their care. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:635–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, et al. What can hospitalized patients tell us about adverse events? Learning from patient-reported incidents. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:830–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Weingart SN, et al. Comparing patient-reported hospital adverse events with medical record review: do patients know something that hospitals do not? Ann Intern Med 2008;149:100–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Averbeck BM, et al. Can patient safety be measured by surveys of patient experiences? Jt Comm J QualPatient Saf 2008;34:266–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2009(3):CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mumford E, Schlesinger HJ, Glass GV. The effect of psychological intervention on recovery from surgery and heart attacks: an analysis of the literature. Am J Public Health 1982;72:141–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Begg C, Berlin J.N.J. Publication bias: a problem in interpreting medical data. J R Stat SocSer A 1988;151 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burgers JS, Voerman GE, Grol R, et al. Quality and coordination of care for patients with multiple conditions: results from an international survey of patient experience. Eval Health Prof 2010;33:343–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vincent C. Understanding and responding to adverse events. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1051–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agoritsas T, Bovier PA, Perneger TV. Patient reports of undesirable events during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:922–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jackson JL, Chamberlin J, Kroenke K. Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:609–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Safran DG, Miller W, Beckman H. Organizational dimensions of relationhip-centred care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;21:S9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alamo MMo, Moral RR, Pérula de Torres LA. Evaluation of a patient-centred approach in generalized musculoskeletal chronic pain/fibromyalgia patients in primary care. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fan VS, Reiber GE, Diehr P, et al. Functional status and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:452–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ 2001;323:908–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA 1997;277:553–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Slatore , Christopher G, Cecere , et al. Patient-clinician communication: associations with important health outcomes among veterans with COPD. Northbrook, ETATS-UNIS: American College of Chest Physicians, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee Y-Y, Lin JL. The effects of trust in physician on self-efficacy, adherence and diabetes outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2009;68: 1060–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee Y-Y, Lin JL. Do patient autonomy preferences matter? Linking patient-centered care to patient-physician relationships and health outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1811–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kennedy A, Nelson E, Reeves D, et al. A randomised controlled trial to assess the impact of a package comprising a patient-orientated, evidence-based self-help guidebook and patient-centred consultations on disease management and satisfaction in inflammatory bowel disease. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England) 2003;7:iii, 1–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kinnersley P, Stott N, Peters TJ, et al. The patient-centredness of consultations and outcome in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:711–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fremont A, Cleary P, Hargraves J, et al. Patient-centered processes of care and long-term outcomes of myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:800–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riley DL, Stewart DE, Grace SL. Continuity of cardiac care: cardiac rehabilitation participation and other correlates. Int J Cardiol 2007;119:326–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blasi ZD, Harkness E, Ernst E, et al. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2001;357:757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, et al. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: a systematic review. Phys Ther 2010;90:1099–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stevenson FA, Cox K, Britten N, et al. A systematic review of the research on communication between patients and health care professionals about medicines: the consequences for concordance. Health Expect 2004;7:235–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care 1988;26:657–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J 1995;152:1423–33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Famy Pract 2002;15:25–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Richards HL, Fortune DG, Griffiths CEM. Adherence to treatment in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:370–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.