Abstract

Background

Refeeding syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition characterised by severe intracellular electrolyte shifts, acute circulatory fluid overload and organ failure. The initial symptoms are non-specific but early clinical features are severely low-serum electrolyte concentrations of potassium, phosphate or magnesium. Risk factors for the syndrome include starvation, chronic alcoholism, anorexia nervosa and surgical interventions that require lengthy periods of fasting. The causes of the refeeding syndrome are excess or unbalanced enteral, parenteral or oral nutritional intake. Prevention of the syndrome includes identification of individuals at risk, controlled hypocaloric nutritional intake and supplementary electrolyte replacement.

Objective

To determine the occurrence of refeeding syndrome in adults commenced on artificial nutrition support.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Large, single site university teaching hospital. Recruitment period 2007–2009.

Participants

243 adults started on artificial nutrition support for the first time during that admission recruited from wards and intensive care.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcome: occurrence of the refeeding syndrome. Secondary outcome: analysis of the risk factors which predict the refeeding syndrome. Tertiary outcome: mortality due to refeeding syndrome and all-cause mortality.

Results

133 participants had one or more of the following risk factors: body mass index <16–18.5≥(kg/m2), unintentional weight loss >15% in the preceding 3–6 months, very little or no nutritional intake >10 days, history of alcohol or drug abuse and low baseline levels of serum potassium, phosphate or magnesium prior to recruitment. Poor nutritional intake for more than 10 days, weight loss >15% prior to recruitment and low-serum magnesium level at baseline predicted the refeeding syndrome with a sensitivity of 66.7%: specificity was >80% apart from weight loss of >15% which was 59.1%. Baseline low-serum magnesium was an independent predictor of the refeeding syndrome (p=0.021). Three participants (2% 3/243) developed severe electrolyte shifts, acute circulatory fluid overload and disturbance to organ function following artificial nutrition support and were diagnosed with refeeding syndrome. There were no deaths attributable to the refeeding syndrome, but (5.3% 13/243) participants died during the feeding period and (28% 68/243) died during hospital admission. Death of these participants was due to cerebrovascular accident, traumatic injury, respiratory failure, organ failure or end-of-life causes.

Conclusions

Refeeding syndrome was a rare, survivable phenomenon that occurred during hypocaloric nutrition support in participants identified at risk. Independent predictors for refeeding syndrome were starvation and baseline low-serum magnesium concentration. Intravenous carbohydrate infusion prior to artificial nutrition support may have precipitated the onset of the syndrome.

Keywords: Nutrition & Dietetics

Article summary.

Article focus

Hypothesis: the risk factors for refeeding syndrome are weak and cause unnecessary delay of nutrition.

Research question: which risk factors reliably predict development of the refeeding syndrome?

Key messages

The refeeding syndrome is a complex constellation of major characteristics which requires a multifacet diagnostic criteria.

The refeeding syndrome is a rare, survivable phenomena that can occur despite identification of risk and hypocaloric nutritional treatment.

Intravenous glucose infusion prior to artificial nutrition support can precipitate the refeeding syndrome.

Starvation is the most reliable predictor for onset of the syndrome.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The authors were not involved in the nutritional treatment, electrolyte supplementation or diagnosis of refeeding syndrome.

The diagnostic criteria provided unequivocal confirmation of the refeeding syndrome and omitted borderline results.

The main source of data loss was the excluded group which may potentially have contained participants who went on to develop the refeeding syndrome.

Introduction

Refeeding syndrome has been defined as severe fluid and electrolyte shift in malnourished patients during oral, enteral or parenteral refeeding.1 A key risk factor for the syndrome is starvation with early published reports being prisoners of war.2 In recent times, refeeding syndrome has been confirmed in hunger strikers, individuals with anorexia nervosa and chronic alcoholics. The modern definition of refeeding syndrome is life-threatening, severely low-serum electrolyte concentrations, fluid and electrolyte imbalance and disturbance of organ function resulting from over-rapid or unbalanced nutrition support.3 However, this definition is imprecise and lacks definitive electrolyte threshold values to confidently diagnose the refeeding syndrome.

The metabolic shift from starvation to feeding increases cellular uptake of glucose, potassium, phosphate and magnesium which lowers the serum concentration of these electrolytes.4 The early signs of the refeeding syndrome are non-specific but include severely low-serum electrolyte concentrations of serum phosphate, potassium and magnesium which, if untreated, can progress to acute circulatory fluid overload, respiratory compromise and cardiac failure.5 Severe hypophosphataemia has been described as the hallmark of the refeeding syndrome.

Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of refeeding syndrome advise identification of individuals at risk, controlled hypocaloric nutritional treatment and supplementary electrolytes.3 However, not all individuals with risk factors for refeeding syndrome develop symptoms during nutritional repletion.6 A potential consequence of adherence to these untested guidelines is the delay of adequate nutrition to undernourished individuals. We conducted a prospective cohort study to determine the occurrence of refeeding syndrome in adults started on artificial nutrition support. Refeeding syndrome was confirmed using a three-facet diagnostic criteria of defined severely low-serum electrolyte concentrations, acute circulatory fluid overload and organ dysfunction.

Methods

Study design

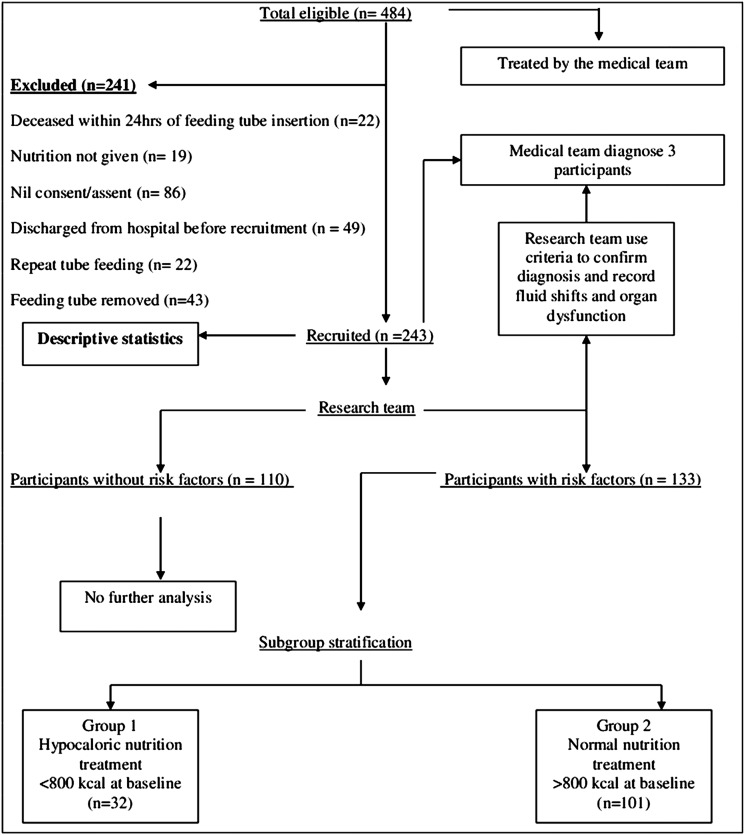

This was a prospective cohort study conducted at a large, single-site university teaching hospital. Criteria to determine risk of refeeding syndrome is displayed in table 1. The risk factors were body mass index <16 (kg/m2), unintentional weight loss >15% in the preceding 3–6 months, very little or no nutritional intake for more than 10 days and low levels of serum potassium, phosphate or magnesium prior to artificial nutrition support. The three-facet diagnostic criteria used by the research team to confirm refeeding syndrome is displayed in table 2. Each participant's medical team diagnosed the refeeding syndrome using serum electrolyte shifts and observed clinical complications of acute circulatory fluid overload and organ dysfunction. The medical teams documented this information in the participant's medical record as daily clinical observations and treatment. The research team used the participant's medical record to confirm that symptoms occurred from the onset of artificial nutrition support recording observations daily and serum electrolyte concentrations every third day from baseline. For each participant diagnosed with the refeeding syndrome, the research team compared the serum electrolyte concentrations, the acute circulatory fluid overload and organ dysfunction against the three-facet diagnostic criteria. All three facets of the diagnostic criteria were required by the research team to unequivocally confirm the diagnosis of refeeding syndrome. To avoid any potential bias, the authors were not involved in nutritional treatment, electrolyte supplementation or the initial diagnosis of refeeding syndrome during the study period. The schematic for participant exclusion, recruitment and analysis is displayed in figure 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for determination of refeeding syndrome risk3

| One of the following: | Two of the following: |

|---|---|

| BMI<16 (kg/m2) | BMI<18.5 (kg/m2) |

| Unintentional weight loss >15% in the preceding 3–6 months | Unintentional weight loss >10% in the preceding 3–6 months |

| Very little or no nutritional intake for more than 10 days | Very little or no nutritional intake for more than 5 days |

| Low levels of serum potassium, phosphate or magnesium prior to feed | History of alcohol or drug abuse |

Table 2.

Criteria for confirmation of refeeding syndrome from the start of artificial nutrition support

| 1. Electrolytes | Severely low electrolyte concentrations4 |

| Potassium | <2.5 mmol/l* |

| Phosphate | <0.32 mmol/l |

| Magnesium | <0.5 mmol/l |

| 2. Peripheral oedema or acute circulatory fluid overload | |

| 3. Disturbance to organ function including respiratory failure, cardiac failure and pulmonary oedema |

*King's College Hospital: severely low-serum potassium concentration which required supplementation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing number of participants at each stage of the study and stratification.

Sample size

The sample size was estimated from the reported prevalence of the refeeding syndrome, defined as hypophosphataemia <0.4 mmol/l, to be 1–10%.7 8 A cohort of 240 would produce between 2 and 24 potential participants meeting the diagnostic criteria.

Participants

Participants, started on enteral or parenteral artificial nutrition support, were eligible to be recruited if they met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria was adults >18 years of age started on artificial nutrition support for the first time during that hospital admission. Exclusion criteria were previous artificial nutrition support during hospital admission, artificial nutrition support started at the previous institution, participants <18 years of age or failure to obtain consent/assent due to serious illness or lack of next of kin. Informed consent was obtained from participants or next of kin prior to enrolment. Study participation was for the duration of artificial nutrition support to a maximum of 15 consecutive days. All the participants were recruited within 48 h of commencement of artificial nutrition support with enteral or parenteral feeding. Energy prescriptions for each participant were estimated by the dietetic specialty who used basal metabolic rate and stress-related factors.9 The hospital nutrition policy for adults with risk factors for refeeding syndrome was 800 kcal/day or 50% of estimated adult energy requirements.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of interest in this study was the occurrence of refeeding syndrome. The secondary outcome was analysis of the risk factor at predicting refeeding syndrome. The tertiary outcome measure was mortality due to refeeding syndrome and all-cause mortality.

Data collection

Baseline serum electrolyte concentrations were recorded within 24 h of study enrolment, then every third day for a maximum of 15 days during the period of artificial nutrition support. Serum electrolytes were not recorded when artificial nutrition support was stopped. Serum electrolyte concentrations were obtained from the hospital electronic inpatient system (iSoft, V.1.0 Oxon, England). The normal hospital adult serum reference ranges were potassium 3.5–5 mmol/l, phosphate 0.8–1.4 mmol/l and magnesium 0.7–1.00 mmol/l. Body weight (kg) was measured using balance and digital scales accurate to within 0.1 kg (Seca, 22089 Hamburg, Germany) wearing light indoor clothing. Body weight was not recorded in participants who were sedated or unconscious. Height (m) was recorded using measured or recalled data as appropriate. Body mass index (kg/m2) and percentage weight loss (normal body weight—current body weight/normal body weight ×100) were calculated. To determine which participants had poor nutritional intake prior to artificial nutrition support, dietary caloric intake was calculated by a research assistant. Each participant was asked to recall their dietary food and fluid intake in the 10 days preceding recruitment into the study. Food portion sizes were estimated from a reference guide10 and total daily energy intake was calculated using a nutritional analysis software package, (Compeat, Oxon, England)11 If the participants were unable to provide a diet history, the next of kin was interviewed; failing this, retrospective food-intake records were used.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed on the entire cohort of 243 participants to obtain diagnostic data, electrolyte supplementation and caloric intake. Each participant was classified at risk or not at risk of refeeding syndrome as per the diagnostic criteria displayed in table 1. Sensitivity and specificity values for refeeding syndrome were calculated for the entire cohort of 243 participants. The precision of the sensitivity and specificity analysis was set at 70%. Predictor variables were transformed to binary categories representing whether or not refeeding syndrome had been diagnosed. The refeeding syndrome outcomes were analysed using Fisher's exact test at the p<0.05 level. A subgroup analysis of the 133 participants with risk factors for refeeding syndrome was performed to provide data on the secondary outcome measure of the study. This subgroup analysis stratified these 133 participants according to their baseline energy intake as Group 1 <800 kcal/day versus Group 2 >800 kcal/day (figure 1). This stratification of baseline energy intake allowed hypocaloric versus normal caloric intake to be analysed. There was no further analysis of the 110 participants without risk factors who did not develop symptoms of the syndrome. All data analysis was performed using SPSS V.17 (Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

A total of 484 participants were eligible to be recruited (figure 1). A total of 243 participants were recruited: median age 57 years (IQR 44.0–69.0), sex 130 (53.5%) men. There were 133 participants with risk factors for refeeding syndrome of which 68 were men. Recruitment locations were wards 153 (63.0%), high dependency unit 46 (18.9%) and intensive care 44 (18.1%) (table 3). In total, 212 (87.2%) participants received enteral; 23 (9.5%) participants parenteral; and 8 (3.3%) received enteral/parenteral tube feeding. There were 2615 total feed days, median duration 13 days (IQR 6–15). A total of 2765 serum electrolyte results were recorded, 1014 for potassium, 1006 for phosphate and 745 for magnesium. The total number of participants who received electrolyte supplementation were potassium 71, magnesium 52 and phosphate 49. Occurrence of moderate and severely low-serum electrolyte concentration with mortality is displayed in table 4. Mortality was not attributed to refeeding syndrome either during feeding (5.3%, 13/243) or hospital admission (28%, 68/243). Cause of death in these participants was due to underlying disease with mortality by location: ward 45/153, high dependency unit 14/46 and intensive care 9/44.

Table 3.

Cohort information, diagnostic data, supplementation totals and energy intake (n=243)

| Location |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Ward (n=153) | HDU (n=46) | ICU (n=44) |

| Male | 78 | 25 | 27 |

| Female | 75 | 21 | 17 |

| Age | |||

| Median | 62.0 | 53.0 | 52.5 |

| IQR | 47.0–73.0 | 39.0–67.5 | 41.0–61.7 |

| Diagnostic categories | |||

| Neurological | 39 | 20 | 16 |

| Respiratory | 6 | 5 | 2 |

| Trauma | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Medicine | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatology | 25 | 2 | 10 |

| Renal | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Pancreas | 9 | 0 | 1 |

| Gastroenterology | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| Cancer | 13 | 2 | 0 |

| Cardiovascular | 22 | 9 | 4 |

| Surgical | 7 | 1 | 5 |

| Sepsis | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Length of stay (days) | |||

| Median | 28.5 | 38.0 | 29.5 |

| IQR | 17.0–47.5 | 17.0–67.5 | 20.5–42.7 |

| Electrolyte supplementation totals | |||

| Potassium | 72 | 29 | 37 |

| Phosphate | 48 | 24 | 21 |

| Magnesium | 46 | 28 | 35 |

| B vitamin supplementation | |||

| Totals | 43 | 10 | 8 |

| Duration of artificial nutrition (days) | |||

| Median | 10.5 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| IQR | 5.0–15.0 | 9.5–15.0 | 12.3–15.0 |

| Energy intake kcal /day | |||

| Baseline | |||

| Median (IQR) | 675 (390–1300) | 690 (480–1000) | 760 (420–1124) |

| Day 3 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1113 (848–1600) | 1440 (1120–1606) | 1470 (1005–1809) |

| Day 6 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1547 (1094–1850) | 1500 (1292–1826) | 1370 (965–1750) |

| Day 9 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1500 (900–1877) | 1449 (960–1700) | 1590 (1200–1907) |

HDU, high dependency unit; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, IQR at 25th and 75th centiles.

Table 4.

Moderately and severely low-serum electrolyte values with mortality (total participants=243)

| Number of electrolyte values recorded | Number of moderately low values | Mortality | Number of severely low values | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium | <3.4 mmol/l | <2.5 mmol/l | ||

| Baseline (n 243) | 20 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Day 3 (n 226) | 22 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Day 6 (n 180) | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Day 9 (n 152) | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Phosphate | <0.5 mmol/l | <0.32 mmol/l | ||

| Baseline (n 243) | 7 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Day 3 (n 222) | 15 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Day 6 (n 177) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Day 9 (n 151) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Magnesium | <0.6 mmol/l | <0.5 mmol/l | ||

| Baseline (n 243) | 14 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Day 3 (n 164) | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Day 6 (n 132) | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Day 9 (n 112) | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

Normal hospital reference ranges potassium 3.5–5.0 mmol/l, phosphate 0.8–1.4 mmol/l and magnesium 0.7–1.00 mmol/l.

Using the criteria in table 2 the research team confirmed the diagnosis of refeeding syndrome in three participants, asymptomatic electrolyte depletion in two participants and the remaining 238 participants did not develop symptoms. Poor nutritional intake for more than 10 days, weight loss >15% prior to recruitment and a low-serum magnesium level at baseline had sensitivity values of 66.7%. By contrast, all specificity values were high (>80%) apart from weight loss >15%, which had a specificity of 59.1%. Low baseline serum magnesium (p=0.021) independently predicted refeeding syndrome: other independent variables were not significantly associated. The pre-existing risk factors for refeeding syndrome within groups one and two are displayed in table 5. Characteristics of the three participants diagnosed with refeeding syndrome are displayed in table 6. Number of participants in the two risk groups that received electrolyte supplementation is displayed in table 7.

Table 5.

Malnutrition profiles of the two groups

| Risk factors | Group 1 Hypocaloric nutrition <800 kcal/day at baseline (n=32) | Group 2 Normal nutrition >800 kcal at baseline (n=101) | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI<(16 kg/m2) | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| BMI<(14 kg/m2) | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Weight loss >15% | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| within the previous 3–6 months | |||

| Poor nutritional intake >10 days | 20 | 15 | 35 |

| Low baseline serum electrolyte concentrations | |||

| Potassium <3.5 mmol/l | 14 | 6 | 20 |

| Phosphate <0.8 mmol/l | 20 | 14 | 34 |

| Magnesium <0.7 mmol/l | 11 | 10 | 21 |

Figures are totals within each group.

Table 6.

Characteristics of the three participants confirmed with refeeding syndrome

| Participant x | Participant y | Participant z | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48 | 23 | 31 |

| Diagnostic group | Trauma | Gastroenterology | Hepatology |

| Chronic condition | Alcoholism | Malnutrition | Alcoholism |

| Route of artificial nutrition support | Enteral | Enteral | Enteral |

| Baseline received energy (kcal/day) | 800 | 294 | 325 |

| Baseline energy (kcal/kg) | 12.7 | 6.3 | 8.1 |

| Potassium replacement | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Phosphate replacement | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Magnesium replacement | No | No | Yes |

| Body weight/kg | 63 | 47 | 40 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20 | 16 | 16 |

| Intravenous carbohydrate | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Survival outcome | Survived | Survived | Survived |

BMI, body mass index.

Table 7.

Number of participants in the two risk groups that received electrolyte supplementation

| Group 1 Hypocaloric nutrition <800 kcal/day at baseline (n=32) | Group 2 Normal nutrition >800 kcal at baseline (n=101) | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| Potassium | 28 | 22 |

| Phosphate | 21 | 19 |

| Magnesium | 20 | 20 |

| Day 3 | ||

| Potassium | 8 | 34 |

| Phosphate | 6 | 30 |

| Magnesium | 5 | 32 |

| Day 6 | ||

| Potassium | 8 | 34 |

| Phosphate | 5 | 30 |

| Magnesium | 7 | 32 |

| Day 9 | ||

| Potassium | 4 | 27 |

| Phosphate | 5 | 22 |

| Magnesium | 3 | 21 |

Participant diagnosed with refeeding syndrome

A 48-year-old woman presented with confusion, bilateral leg weakness, alcohol withdrawal, poor nutritional intake with repeat vomiting for 7 days, C2 fracture, translocation at C2/3 and high urinary ketones. The participant received two intravenous doses of standard vitamins B and C formulation in 0.9% NaCl followed by 100 mg oral thiamine. On day 2, the patient received 1 litre of intravenous potassium chloride and 2 litres of 5% glucose followed by enteral tube feeding. On day 3, serum phosphate was recorded at 0.33 mol/l and 50 mmol/l intravenous phosphate in 500 ml was infused over 12 h. On day 4, the participant developed peripheral oedema with tachycardia and was transferred to the intensive care unit due to respiratory failure and acute circulatory fluid overload.

Another participant, a 23-year-old woman, with Crohn's disease and subtotal bowel colectomy presented with frontal occipital headaches radiating to the neck with a history of nausea, vomiting and weight loss of 26 kg. At day 117 of admission, a nasogastric tube was inserted owing to poor nutritional intake. Nutrition was stopped within 2 h owing to vomiting and abdominal pain. The participant collapsed 24 h later due to hypotension, hypothermia, dehydration and pseudobowel obstruction. The participant was transferred to the high-dependency unit for fluid resuscitation. Intravenous 10% glucose was started, and a 16 French wide bore nasogastric tube was inserted for gastric drainage. On day 2, serum electrolytes levels were potassium 3.2 mmol/l, phosphate 0.26 mmol/l and magnesium 0.55 mmol/l. Intravenous phosphate replacement was started with 50 mmol/l phosphate in 500 ml. The participant was transferred to the intensive care unit, intubated and started on haemofiltration owing to multiorgan failure.

Another participant, a 31-year-old woman, with decompensated liver cirrhosis secondary to alcohol, with existing chronic pancreatitis and opiate dependency with a weekly alcohol intake of 56 units was admitted to the hepatology unit with abdominal pain, vomiting and dehydration. Usual body weight was 48 kg; admission dry weight was 40 kg. The participant received a standard formulation of vitamins B and C followed by 1 litre of 5% glucose containing 20 mmol/l KCl. Oral thiamine 100 mg and oral vitamin B compound were prescribed. The participant had a nasogastric tube inserted for artificial nutrition support. On day 3, serum electrolytes were potassium 2.5 mmol/l, phosphate 0.37 mmol/l and magnesium 0.56 mmol/l. The participant developed acute circulatory fluid overload and symptoms of tachycardia and pneumonia. The participant was given 50 mmol/l intravenous phosphate in 500 ml infused over 12 h in 1 litre of 5% glucose, 25 mmol magnesium and a repeat intravenous dose of a standard vitamin B and C formulation.

Discussion

This study applied a three facet diagnostic criteria to confirm the occurrence of refeeding syndrome in adults started on artificial nutrition support. This unequivocal clinical diagnostic criteria comprised of defined severe serum electrolyte concentrations, acute circulatory fluid overload and organ dysfunction. These symptoms occurred within 72 h of hypocaloric artificial nutrition support in three participants identified at risk. Two participants developed respiratory failure and multiorgan failure and required admission to the intensive care unit while the third participant, who developed acute circulatory fluid overload and tachycardia, was treated on the ward. The survival of these three participants represents advances in the medical management of severely malnourished individuals compared with the fatal outcome of early reports.2 5 This study does not support previous reports that refeeding syndrome can be prevented by identification of risk and treatment with hypocaloric feeding. In this study, refeeding syndrome occurred in three participants who had been identified at risk and treated with hypocaloric feeding. Risk factors distinct to the three refeeding syndrome participants were a history of starvation and baseline low-serum magnesium concentration. Two of the three participants received an intravenous dose of standard vitamins B and C formulation, prior to artificial nutrition support which may have prevented Wernicke's encephalopathy. The small number of participants diagnosed with refeeding syndrome in this study may have been due to the medical teams having a policy of early electrolyte replacement. However, we suspect that the most compelling reason for the low occurrence of refeeding syndrome, in this study, was that starvation was a characteristic of only three participants. The analysis of the two subgroups showed strikingly similar malnutrition profiles but substantially different energy intakes. We interpret this to suggest that for the refeeding syndrome to occur a risk factor was required. The compelling risk factor of the three diagnosed participants was starvation. This interpretation is supported by the analysis of those participants who reported a short period of fasting, prior to artificial nutrition support, and experienced moderate falls in their serum electrolyte concentrations.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution. The study was not designed to assess the mechanism of the refeeding syndrome. The strengths of the study were standardised diagnostic criteria, risk factor analysis and comparison of the hypocaloric and normal caloric nutrition groups. The results have limited external validity due to the inherent bias of narrow selection criteria. This selection bias effect and exclusion of participants who were able to take oral nutritional intake may explain the low occurrence of the refeeding syndrome recorded in the study population. A large number of potentially eligible participants could not be recruited due to difficulty in obtaining consent. A further reduction in potential participants was death within 24 h of commencing artificial nutrition support. The causes of death in these participants were due to their underlying medical condition of cerebrovascular accident, traumatic injury, respiratory failure due to degenerative neurological disease, organ failure or end-of-life causes. Since death occurred within 24 h of starting artificial nutrition support, we cannot exclude complications of refeeding syndrome as a contributing factor. Confusion, communication impairment and cognitive problems due to refeeding syndrome may also explain why a large number of severely ill individuals refused participation in this cohort study. Equally valid is the possibility that these severely ill individuals refused participation due to the limited benefit inclusion in this study would provide.

The diagnosis of only three participants limited the statistical analyses that we could perform which excluded regression analyses. The low occurrence of refeeding syndrome may have been due to the medical teams taking preventative actions such as early electrolyte replacement. Severely low electrolyte concentrations may be interpreted as too low to confirm the syndrome. However, the serum electrolyte concentrations were obtained from a review of the evidence to enable an unequivocal diagnosis of the refeeding syndrome. This discreet approach was taken to avoid falsely diagnosing participants with single, abnormal electrolyte concentrations. While the review of evidence was consistent for severely low-serum electrolyte concentrations, the authors identified a lack of consensus on the electrolyte concentration values to diagnose the syndrome. To avoid bias, the authors were not involved in nutritional treatment, electrolyte supplementation or initial diagnosis of the syndrome.

Interpretation

Occurrence of serum phosphate <0.5 mmol/l in this study was 3% on day 1 and 6% on day 3 which was higher than that reported in the adult hospital population of 0.2–2%.7 8 12 13 The higher occurrence of hypophosphataemia in this study may have been due to the cohort containing participants recruited from the high dependency and intensive care units. Very few participants developed severe electrolyte shifts, although moderate serum concentrations of potassium, phosphate and magnesium occurred. The interpretation of moderate electrolyte shifts, without symptoms of the syndrome, was cellular uptake of electrolytes in response to nutritional input. The subgroup analysis identified many participants with risk factors for the syndrome. Hypocaloric nutritional treatment may have prevented refeeding syndrome in some of these participants. However, the subgroup analysis revealed that one group received more energy sooner and for longer but did not develop symptoms. Applying the diagnostic criteria in table 2 revealed the risk factors3 to be weak predictors of the syndrome.

The impact of intravenous glucose infusion, without adequate and repeated electrolyte replacement in the three diagnosed participants, cannot be under estimated. In starved individuals gluconeogenesis is the predominant metabolic pathway for energy production. Infusion of intravenous glucose potentially suppressed gluconeogenesis which caused a switch to glycolysis in these three participants. This switch caused insulin to be released causing rapid cellular uptake of serum phosphate, potassium and magnesium electrolytes. We propose that the initial infusion of glucose in the three starved participants potentially triggered the metabolic sequence that resulted in development of the syndrome. Hypocaloric feeding failed to prevent refeeding syndrome in these three participants for one important reason, it continued the input of simple carbohydrates causing more insulin to be released. This explanation is supported by other studies where intravenous glucose infusion was attributed to hypophosphataemia of <0.7 mmol/l14 which progressed to respiratory failure at serum phosphate concentration 0.2–0.36 mmol/l.15–17 The results of the present study indicate that glucose infusion should be avoided in starved individuals who require fluid and nutritional treatment. The finding that intravenous glucose infusion in starved individuals may initiate the refeeding syndrome requires further research. A potential hypothesis to be tested is that electrolyte replacement strategies are more effective at preventing the syndrome than caloric restriction.

Comparison with other studies

The era of hypercaloric feeding in cachectic individuals was associated with cardiac abnormalities,18 respiratory failure and death.5 Two decades later, controlled hypocaloric nutritional treatment and electrolyte supplementation prevented refeeding syndrome in eight prisoners who had been on hunger strike for 43 days.19 Under controlled conditions, hypocaloric nutritional treatment and intravenous phosphate containing 25 mmol/l over 12 h with effervescent oral phosphate (16 mmol) twice daily prevented serious complications associated with refeeding syndrome in a 30-year-old man who endured 44 days of self-imposed starvation.20 Refeeding syndrome was prevented in 29 anorexia nervosa participants given 500–2000 mg phosphate daily.21 The energy prescription was 1900 kcal at day 1 and 2200 kcal at day 3 yet moderate hypophosphataemia (0.31–0.8 mmol/l) did not occur. These varied studies reflect increased awareness of the syndrome where serious complications and mortality can be avoided.22 23 In the present study, refeeding syndrome was a rare, survivable phenomenon that occurred in starved individuals who crucially were identified at risk and treated with hypocaloric nutrition.24 However, intravenous glucose infusion prior to artificial nutrition support may have triggered the onset of refeeding syndrome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Charlotte Ellerton, Sheetal Gohil, Catherine Fleuret, Jessica Zubek, Sharon Wheelock, Joanna Lam, Abigail Wilson and Lucy Diamond for participant recruitment and the medical and nursing staff who completed the enteral and parenteral feeding charts.

Footnotes

Contributors: AR was responsible for the conception, design, initiation and overall co-ordination of the study: AR drafted the paper, was responsible for its intellectual content, interpretation and analysis of the results. KW was involved in the design of the study, interpretation of results and writing the manuscript. NS conducted statistical analysis, interpretation of results and editing of the manuscript. DR and LG assisted with data collection and interpretation of the results: AR is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethical approval: King's College Hospital Research Ethics Committee (06/Q0703/131).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Solomon SM, Kirby DF. The refeeding syndrome: a review. JPEN 1990;14:90–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnitker MA, Mattman PE, Bliss TL. A clinical study of malnutrition in Japanese prisoners of war. Ann Intern Med 1951;35:69–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Nutrition support in adults. National Collaborating Center for Acute Care. London, The Royal Surgeons of England [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crook MA, Hally V, Panteli JV. The importance of the refeeding syndrome. Nutrition 2001;17:632–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinsier RL, Krumdieck CL. Death resulting from overzealous total parenteral nutrition: The refeeding syndrome revisited. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:393–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeki S, Culkin A, Gabe SM, et al. Refeeding hypophosphataemia is more common in enteral than parenteral feeding in adult patients. Clin Nutr 2011;30:365–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaganski M, Levy S, Koren-Morag N, et al. Hypophosphataemia in the elderly is associated with the refeeding syndrome and reduced survival. J Intern Med 2005;257:461–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flesher ME, Archer KA, Leslie BD, et al. Assessing the metabolic and clinical consequences of early enteral feeding in the malnourished patient. JPEN 2005;29:108–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schofield WN, Schofield C, James WPT. Basal metabolic rate. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr 1985;39:1–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawley H. Food portion sizes. London: HMSO, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compeat, Nutrition Systems, Oxon,

- 12.King AL, Sica DA, Miller G, et al. Severe hypophosphataemia in a general hospital population. South Med J 1987;80:831–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman M, Zemlin AE, Meyer WP, et al. Hypophosphataemia at a large academic hospital in south Africa. J Clin Pathol 2008;61:1104–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betro MG, Pain RW. Hypophosphataemia and hyperphosphataemia in a hospital population. BMJ 1972;1:273–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillou PJ, Morgan DB, Hill GL. Hypophosphataemia: a complication of innocuous glucose saline. Lancet 1976;308:710–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel U, Sriram K. Acute respiratory failure due to refeeding syndrome and hypophosphataemia induced by hypocaloric enteral nutrition. Nutrition 2009;25:364–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown EL, Jenkins BA Gwynne. A case of respiratory failure complicated by acute hypophosphataemia. Anaesthesia 1980;35:42–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heymsfield SB, Bethel RA, Ansley JD, et al. Cardiac abnormalities in cachectic patients before and during nutritional repletion. Am Heart J 1978;95:584–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faintuch J, Soriano FG, Ladeira JP, et al. Refeeding procedures after 43 days of total fasting. Nutrition 2001;17:100–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korbonitis M, Blaine D, Elia M, et al. Metabolic and hormonal changes during the refeeding period of prolonged fasting. Eur J Endocrinol 2007;157:157–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitelaw M, Gilbertson H, Lam PY, et al. Does aggressive refeeding in hospitalized adolescents with anorexia nervosa result in increased hypophosphataemia? J Adolescent Health 2010;46:577–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cumming AD, Farquhar JR, Bouchier A. Refeeding hypophosphataemia in anorexia nevosa and alcoholism. BMJ 1987;295:490–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terlevich A, Hearing SD, Woltersdorf WW, et al. Refeeding syndrome: effective and safe treatment with Phosphates Polyfusor. Aliment Pharm Therap 2003;7:1325–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ 2008;336:1495–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.