Abstract

Objective

To explore characteristics associated with, and prevalence of, low health literacy in patients recruited to investigate the role of depression in patients on General Practice (GP) Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) registers (the Up-Beat UK study).

Design

Cross-sectional cohort. The health literacy measure was the Rapid Estimate of Health Literacy in Medicine (REALM). Univariable analyses identified characteristics associated with low health literacy and compared health service use between health literacy statuses. Those variables where there was a statistically significant/borderline significant difference between health literacy statuses were entered into a multivariable model.

Setting

16 General Practices in South London, UK.

Participants

Inclusion: patients >18 years, registered with a GP and on a GP CHD register. Exclusion: patients temporarily registered.

Primary outcome measure

REALM.

Results

Of the 803 Up-Beat cohort participants, 687 (85.55%) completed the REALM of whom 106 (15.43%) had low health literacy. Twenty-eight participants could not be included in the multivariable analysis due to missing predictor variable data, leaving a sample of 659. The variables remaining in the final model were age, gender, ethnicity, Indices of Multiple Deprivation score, years of education, employment; body mass index and alcohol intake, and anxiety scores (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale). Univariable analysis also showed that people with low health literacy may have more, and longer, practice nurse consultations than people with adequate health literacy.

Conclusions

There is a disadvantaged group of people on GP CHD registers with low health literacy. The multivariable model showed that patients with low health literacy have significantly higher anxiety levels than people with adequate health literacy. In addition, the univariable analyses show that such patients have more, and longer, consultations with practice nurses. We will collect 4-year longitudinal cohort data to explore the impact of health literacy in people on GP CHD registers and the impact of health literacy on health service use.

Keywords: Health literacy, Cardiovascular disease, Prevalence

Article summary.

Article focus

Identifying the prevalence and characteristics of people with coronary heart disease (CHD) and low health literacy on CHD General Practice (GP) registers in South London, UK.

Key messages

The characteristics of patients with low health literacy on UK GP CHD registers are similar to those seen in other long-term conditions in studies undertaken in other industrialised countries.

The prevalence of low health literacy to be close to that predicted from national general literacy levels at 15%.

People on GP CHD registers who have higher anxiety levels are more likely to have low health literacy than people with lower anxiety levels.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The data were collected within a prospective cohort study.

There was a wide range of sociodemographic data collected enabling characteristics of patients with low health literacy to be described.

The simultaneous collection of psychological and service use data enabled these to be compared between patients with low and adequate health literacy.

As a cross-sectional study this project cannot demonstrate causality or the impact of low health literacy over time.

The findings may underestimate the true picture; the 14.45% of participants who declined to do the Rapid Estimate of Health Literacy in Medicine (REALM) may have declined because of reading difficulties.

Our findings of more frequent, and longer, GP nurse consultations should be interpreted with caution; the above preliminary finding requires more detailed health economic analysis and interpretation.

The REALM, although highly correlated with tests of functional health and general literacy, is not itself a test of functional skills but of pronunciation.

Introduction

Health literacy ‘the cognitive and social skills that determine the motivation and ability of individuals to (access), understand and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health’1 is a social determinant of health.2 While associated with other social determinants, for example, ethnicity, income, education and sociodemographic status, it has an independent association with poor health.3 International comparisons of health literacy levels are hampered by differing national definitions; however, it is clear that health literacy is an important issue in many industrialised nations. The proportion of the population thought to be disadvantaged through low health literacy ranges from 19% in the USA4 to 55% in Canada.5 A recent survey of health literacy in Europe, where a common definition of health literacy was adopted, shows a range of health literacy skills between nations, with the proportion of the population having suboptimal health literacy skills ranging from 27.3% in the Netherlands to 61.4% in Bulgaria.6 There are no data on health literacy levels in England; however, the 2011 national skills survey has shown that 15% of the adult population (=5 million people) are ‘functionally illiterate’7 (ie, have insufficient literacy skills to achieve their potential in life and society8). It is reasonable to assume that a similar proportion also have low health literacy.

Low health literacy has greatest impact in complex health conditions when patients have to understand procedures, manage medication and attend multiple appointments. US studies have shown that adults with low health literacy have increased hospitalisations and greater emergency care use, lower use of preventative care such as mammography and vaccine uptake, poorer ability to demonstrate taking medications appropriately, poorer ability to interpret labels and health messages, and, among seniors, poorer overall health status and higher mortality.9 There is little research on low health literacy and coronary heart disease (CHD), prompting us to explore this within a longitudinal cohort of patients recruited to investigate the role of depression in patients on General Practice (GP) CHD registers.10 This short report presents initial findings on the prevalence and characteristics of people with CHD and low health literacy.

Method

The design, recruitment, power calculation and measures used in the Up-Beat cohort study are described elsewhere.10 The study was granted ethical approval by the Bexley and Greenwich Research Ethics Committee (REC Reference: 07/H0809/38).10 Health literacy was measured using the Rapid Estimate of Health Literacy in Medicine (REALM),11 a 66-item health word pronunciation test highly correlated with other measures of health literacy12 13 and widely used in research studies.3 The version of the REALM validated for use in the UK was used. This groups people into ‘low’ and ‘adequate’ health literacy with people with a score of <59 out of the possible 66 being considered to have low health literacy.14

Study design

A cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from the Up-Beat UK Cohort Study.10

Statistical analysis

Initial exploratory univariable analysis was undertaken to identify factors independently associated with low health literacy using χ² tests (categorical variables) and t tests (continuous variables). Multivariable regression analysis was then undertaken to identify those factors that remained significant when all those identified in the univariable analysis were considered together. Those characteristics where there was a statistically significant (p<0.05) or borderline significant difference between people with low and adequate health literacy were entered into the multivariable model; logistic regression was used to model predictors of low health literacy. The fit for the model was assessed by the C statistic (receiver operating characteristic curve) and the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit χ² test. Analyses were performed using Stata V.11.2.

Results

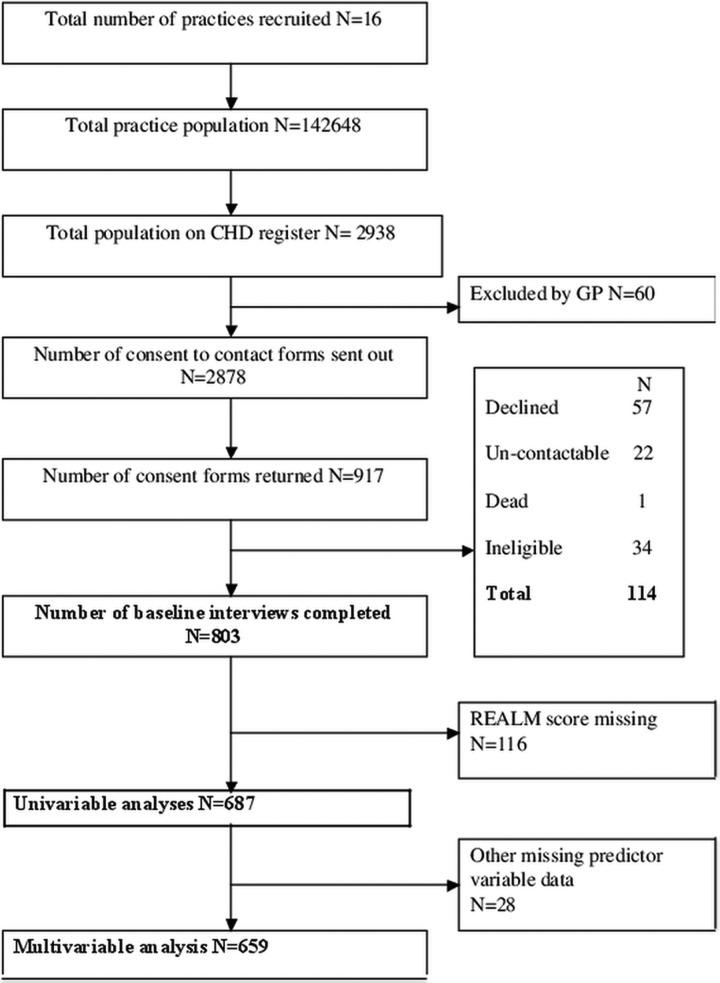

Cohort characteristics are detailed elsewhere.10 Cohort recruitment and a study flow diagram are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Exploring indicators of low health literacy in a cohort with symptomatic coronary heart disease. Study recruitment: consort diagram.

The results of the univariable and multivariable analyses are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics by health literacy

| Health literacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate | Low | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | Univariable analysis N=687 | Multivariable analysis N=659 | ||

| p Value* | Adjusted odds of having low health literacy (p values) | ||||

| Total | 581 (84.57) | 106 (15.43) | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 397 (68.33) | 87 (82.08) | 0.004 | 0.32 (<0.001) | |

| Female | 184 (31.67) | 19 (17.92) | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 524 (90.19) | 81 (76.42) | <0.001 | 3.12 (<0.001) | |

| Other | 57 (9.81) | 25 (23.58) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | |||||

| Years | 71.14 (10.41) | 68.92 (11.84) | 0.049 | 1.00 (0.873) | |

| Index of multiple deprivation score, mean (SD) | |||||

| Range 0–100 | 18.34 (13.84) | 24.37 (13.24) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.072) | |

| Time in education, mean (SD) | |||||

| Years | 12.01 (3.40) | 10.92 (2.46) | <0.001† | 0.84 (0.001) | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Unemployed/student | 14 (2.42) | 10 (9.52) | 0.001 | 0.138 | |

| Paid employment | 117 (20.21) | 18 (17.14) | 0.31 | ||

| Retired/housewife | 448 (77.37) | 77 (73.33) | 0.34 | ||

| Lifestyle characteristics | |||||

| Alcohol intake (units) | |||||

| Does not drink | 136 (23.45) | 44 (41.90) | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| 1–10 | 289 (49.83) | 44 (41.90) | 0.48 | ||

| 11–20 | 87 (15.00) | 9 (8.57) | 0.34 | ||

| Greater than 21 | 68 (11.72) | 8 (7.62) | 0.24 | ||

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight/normal | 145 (25.62) | 15 (14.29) | 0.024 | 0.027 | |

| Overweight | 250 (44.17) | 48 (45.71) | 2.38 | ||

| Obese | 171 (30.21) | 42 (40.00) | 2.50 | ||

| Mental health | |||||

| Depression score, mean (SD) | 2.86 (3.14) | 4.28 (3.76) | <0.001† | ||

| Anxiety score, mean (SD) | 4.39 (4.13) | 6.35 (5.18) | <0.001† | 1.08 (0.002) | |

| Health utilisation in the 6 months prior to baseline | |||||

| Number of practice nurse visits, mean (SD) | 0.89 (1.85) | 1.33 (2.21) | 0.008‡ | ||

| Duration of practice nurse visit, mean (SD) | 4.98 (7.05) | 6.98 (8.30) | 0.008‡ | ||

| All other service use variables§ | 0.120¶–0.793** | ||||

*p Value from t test for continuous variables and χ²-tests for categorical variables.

†Unequal variances t test used.

‡Wilcoxon rank sum test.

§Number of accident and emergency visits, day hospital and inpatient admissions (days), outpatient visits, general practice visits (number and duration), district nurse visits (number and duration), other medical visits (number and duration), other care-based visits (number and duration) and informal care visits number.

¶Number of accident and emergency visits.

**Other care-based visits (duration).

BMI, body mass index.

Of the 803 cohort participants 687 (85.55%) completed the REALM questionnaire. The 116 non-responders were excluded from the analyses. Non-responders lived in more socioeconomically deprived areas and had received fewer years of education than those who completed the REALM. There was no difference in ethnicity (responders vs non-responders).

Of the 687 participants who completed the REALM, 106 (15.43%) had low health literacy. For the multivariable analysis 28 patients could not be included due to missing predictor variable data, leaving a total sample of 659.

Exploratory univariable analyses showed that people with low health literacy were more likely to be male, from a non-white ethnic group, live in a more deprived area, have spent fewer years in education, and were less likely to be employed. Age was borderline significant with people with low health literacy being slightly younger than people with adequate health literacy (difference in mean age between groups 2.22 years).

The variables remaining in the final multivariable model were age, gender, ethnicity (white versus other), Indices of Multiple Deprivation score, years of education, employment; body mass index and alcohol intake, and anxiety scores (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)).15 There was an 8% increase in the odds of low health literacy for every single unit increase in the anxiety score on HADS (range 0–21).

Service use analysis (univariable only) showed that people with low health literacy had significantly more, and longer, GP nurse consultations than people with adequate health literacy, but other service use showed no differences between groups.

Discussion

Key findings

This study confirms that the characteristics of patients with low health literacy on UK GP CHD registers are similar to those seen in other long-term conditions in studies undertaken in other industrialised countries (ie, membership of a minority ethnic group, socioeconomic deprivation, fewer years in education and lower income9). In contrast to other studies,3–6 the patients with low health literacy in our study were slightly younger than the patients with adequate health literacy, although the difference between groups was small and should be interpreted with caution. We found that the prevalence of low health literacy to be close to that predicted from national general literacy levels.7

In addition, people on GP CHD registers who have higher anxiety levels are more likely to have low health literacy than people with lower anxiety levels. This persists in the multivariable model, indicating an association over and above that already known to exist between anxiety and low socioeconomic status.16 17 This may reflect the findings of Ussher et al18 that CHD patients with low health literacy have increased difficulty in understanding information, less knowledge of heart problems and increased discomfort about asking for explanations. The finding in the univariable analysis that patients with low health literacy had more contact with practice nurses but not with other health services requires further investigation.

Summary

Our findings indicate that there is a disadvantaged group of people on GP CHD registers who have low health literacy in addition to other sociodemographic barriers to health. A new finding is that these people have significantly higher anxiety levels than people with adequate health literacy.

Next steps

Our possible finding that people on GP CHD registers with lower health literacy consulted practice nurses more frequently will inform future Up-Beat pilot interventions10 and our longitudinal cohort data will enable us to explore the impact of low health literacy on patients on GP CHD registers, and on their health service use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the 16 South London practices who participated in the UPBEAT-UK study.

Footnotes

Contributors: GPR led on development of the research idea, contributed to interpretation of result and led on writing the paper. AM and SH collected research data and contributed to interpretation of results and writing the paper. RP led on statistical analysis of the data and interpretation of the results. PW conducted additional statistical analysis and contributed to the paper. AM and ATT codeveloped the UPBEAT cohort study in which the study is sited, contributed to the research idea, contributed to interpretation of results and writing the paper. AS contributed to the project design, analysis of results and writing the paper. PW contributed to the research idea, interpretation of the results and writing the paper.

Funding: This report/article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0606-1048). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: AT is partly employed by the NIHR Institute of Psychiatry and South London and Maudsley Foundation Trust Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre.

Ethics approval: Bexley and Greenwich Research Ethics Committee (REC Reference: 07/H0809/38).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nutbeam D. Health Promotion Glossary. Health Promotion International 1998;13:349–64 [Google Scholar]

- 2.CSDH Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008, Final report of the commission on Social Determinants of Health [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, et al. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:175–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd RE. Health literacy skills of U.S. adults. Am J Health Behav 2007;31(Suppl 1):S8–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rootman I, Gordon-El-Bihbety D. A vision for a health literate Canada. Ottowa: Canadian Public Health Association; 2008, Report of the expert panel on health literacy [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle G, Cafferkey K, Fullam J. European Health Literacy Survey (HLSEU) Executive Summary. Dublin: University College Dublin, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skills for life survey: headline findings. London: Department for Business Innovations and Skills; 2011, Research report no: 57 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moser C. A fresh start: the report of the working party on literacy and numeracy. London: Department for Education and Employment, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Rockville, MD 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tylee A, Ashworth M, Barley E, et al. Up-Beat UK: a programme of research into the relationship between coronary heart disease and depression in primary care patients. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993;25:391–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, et al. The Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA): a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10:537–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz Wet al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3:514–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim SY, Reid F, Shaw A, et al. Validation of a health literacy screening tool (REALM) in a UK population with coronary heart disease. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:449–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967;6:278–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff BC, Santiago CD, Wadsworth ME. Poverty and involuntary engagement stress responses: examining the link to anxiety and aggression within low-income families. Anxiety Stress Coping 2009;22:309–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Najman JM, Hayatbakhsh MR, Clavarino A, et al. Family poverty over the early life course and recurrent adolescent and young adult anxiety and depression: a longitudinal study. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1719–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ussher M, Ibrahim S, Reid Fet al. Psychosocial correlates of health literacy among older patients with coronary heart disease. J Health Commun 2010;15:788–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.