Abstract

Objective

To investigate the impact in an aging society of the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake on hospitalisation for respiratory disease at the disaster base hospital.

Design

Descriptive and cross-sectional study.

Setting

Emergency care in Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital, a regional disaster base hospital in Miyagi, Japan.

Participants

322 emergency patients who were hospitalised for respiratory disease from 11 March to 9 May 2011, and 99 and 105 emergency patients who were hospitalised in the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010, respectively.

Main outcome measures

Description and comparison of patient characteristics and disease distribution in terms of age, time after the disaster and activities of daily living (ADL).

Results

1769 patients were admitted to our hospital during the study period (compared to 850 in 2009 and 1030 in 2010), among whom 322 were hospitalised for respiratory disease (compared to 99 in 2009 and 105 in 2010). Pneumonia (n=190, 59.0%) was the most frequent cause of admission for pulmonary disease, followed by acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AE-COPD) (n=53, 16.5%), asthma attacks (n=27, 8.4%) and progression of lung cancer (n=22, 6.8%). Compared with the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010, the increase in the absolute numbers of admissions was highest for pneumonia, followed by AE-COPD and asthma attacks. At hospitalisation, 195 patients were ‘dependent’ and 54 patients were ‘partially dependent’. Respiratory admissions accompanied by deterioration of ADL after the disaster were more frequent in elderly and female patients.

Conclusions

After the Great East Japan Earthquake, admissions for pneumonia and exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease in the elderly increased at the disaster base hospital.

Keywords: Geriatric Medicine, Accident & Emergency Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

The Great East Japan Earthquake affected one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world.

We describe how the disaster affected respiratory diseases in the worst affected area, which has one of the highest ratios of elderly people in Japan.

The study provides lessons for use after natural disasters in an aging society.

Key messages

After the earthquake and tsunami, admissions for pneumonia and exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease increased among the elderly.

Harsh conditions and poor activities of daily living status after the disaster may be associated with increased hospitalisation for respiratory diseases in elderly people.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We were able to obtain detailed patient data after a disaster.

We only studied hospitalised patients, but there were also numerous outpatients, many of whom died.

Introduction

On 11 March 2011, at 14:00 h Japanese time, the Pacific coast of Japan's Tohoku (north-eastern) region was struck by a huge earthquake (The Great East Japan Earthquake) measuring 9.0 on the Richter scale.1 The earthquake triggered a devastating tsunami which destroyed many towns and villages close to the sea. The epicentre was estimated to be about 70 km east of Oshika Peninsula in Miyagi Prefecture. Officially, over 19 000 people were killed or are missing and there were more than 550 000 refugees.2

Ishinomaki city, located on the Pacific coast of Honshu Island, lost the most victims in the disaster, with 3280 people killed and 669 still missing. A huge number of casualties, more than 10 000 patients in the first 30 days, were treated at Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital, a regional disaster base hospital in Ishinomaki which preserved its hospital function during and after the catastrophe.

Japan is one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world. In 2010, 23% of Japanese citizens were aged 65 or over,3 while 26.6% of people living in Ishinomaki city in the Tohoku region were aged 65 or over. Although several reports showed a significant association between age and death following the earthquake and tsunami,4–8 few reports have investigated the impact of a huge disaster on the elderly in an aging society.9 10

As respiratory diseases are common in the elderly, investigating the impact of the disaster on respiratory health will help elucidate the problems of an aging society. Thus, we carried out a retrospective descriptive and cross-sectional analysis of the medical and epidemiological data of patients requiring hospitalisation for respiratory disease after the Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent tsunami.

Methods

This study was a retrospective descriptive and cross-sectional analysis of data obtained from the medical records at Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital. We reviewed the medical records of patients admitted to the hospital for respiratory diseases during the first 60 days after the Great East Japan Earthquake, when the hospital only accepted emergency patients. We also reviewed the medical records of patients who required unscheduled hospitalisation for respiratory disease in the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010.

Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital has 402 inpatient beds and is located 4.5 km inland from the Pacific. It serves approximately 220 000 people (Ishinomaki City, Onagawa Town and Higashi-matsushima City) and was designated a regional disaster base hospital. It normally accepts most emergency respiratory patients in the region because it has a respiratory department and employs pulmonary specialists.

Information on date of admission, age, sex, diagnosis and place of residence was extracted from the medical records for the 2011 study period. We also investigated activities of daily living (ADL) before the earthquake and at hospitalisation. The number of unscheduled hospitalisations during the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010 were counted for comparison.

Pneumonia was defined as the presence of infiltrates on chest radiograph together with one or more of the following signs or symptoms: fever, cough, sputum production, breathlessness, pleuritic chest pain or signs consistent with pneumonia on auscultation.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchial asthma were determined according to spirometric data, patient self-report or physician diagnosis based on patient history, physical examination and radiological findings. An acute exacerbation of COPD (AE-COPD) was defined as an increase in or new onset of more than one symptom of COPD (cough, sputum, wheezing, dyspnoea or chest tightness) without pneumonia or pneumothorax. An attack of asthma was defined as wheeze or severe cough in asthma patients without pneumonia. Progression of lung cancer was defined as a requirement for admission for a lung cancer-associated condition such as dehydration, respiratory failure or uncontrolled pain. Obstructive pneumonia due to lung cancer was considered to be progression of lung cancer. Chest trauma and traumatopnea were deemed to be chest injury rather than respiratory disease.

ADL was assessed based on information provided by the patient, the patient's family or the patient's caregiver, and the patient classified into one of three categories: ‘independent’(living without particular support), ‘partially dependent’ (unable to leave home without support), ‘dependent’ (spending the day in bed or in a wheelchair and unable to move about independently). To investigate the impact of the disaster on ADL, we defined as ‘originally dependent’ those who were dependent or partially dependent before the disaster, and as ‘newly dependent’ those who became dependent or partially dependent after the disaster.

Data analysis

All data were entered into a personal computer and analysed using Microsoft Excel software. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP9 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A missing value in a medical record was treated as ‘unknown’. Results were given as means±SD for numerical variables and as proportions for categorical variables. To analyse sequential changes in the effects of the disaster, we divided the 60 days of the study period into six groups of 10-day bins. To investigate the risk of hospitalisation for respiratory disease after the earthquake and tsunami, we compared patient characteristics for the 2011 study period with the combined data for the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010. We used a two-sided Student t test for numerical variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

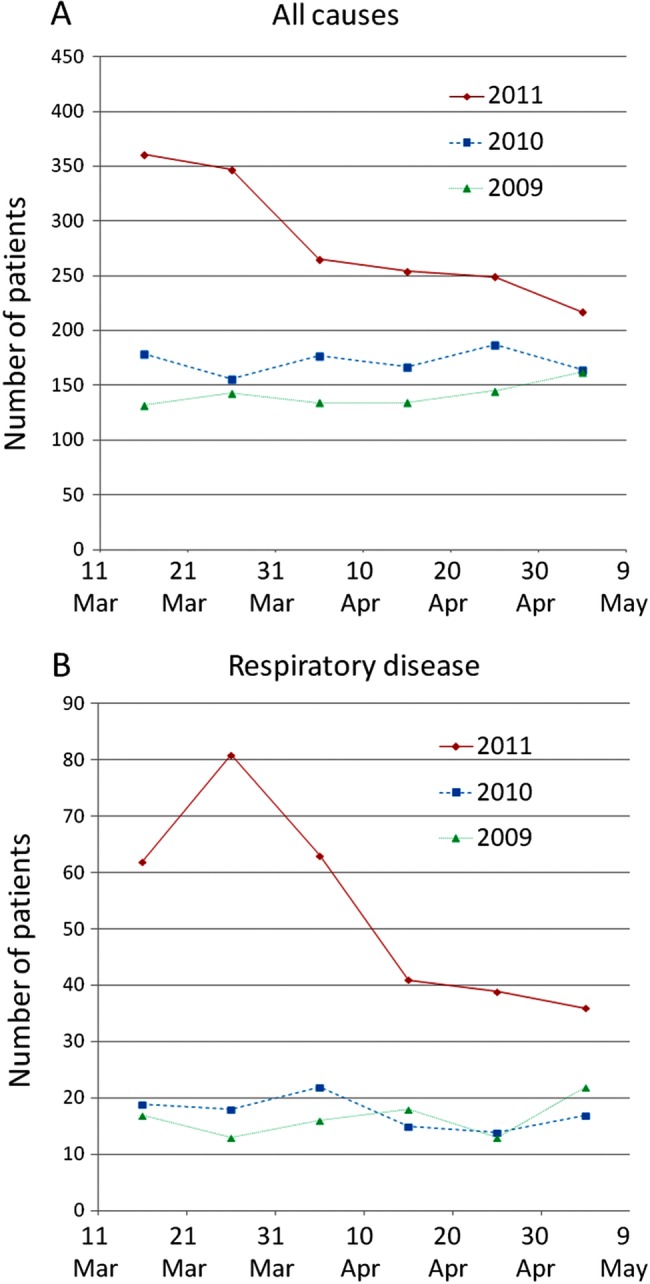

For the first 60 days following the earthquake, all scheduled admissions to Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital were cancelled and only emergency admissions were accepted. During this period, 1769 patients were admitted to the hospital, 322 of whom were hospitalised for respiratory disease. In the corresponding periods in 2009 and 2010, there were 850 (99 for respiratory disease) and 1030 (105 for respiratory disease) unscheduled admissions, respectively. Patients hospitalised for respiratory disease accounted for 18.2% of total admissions during the 2011 study period. This proportion was significantly higher than that in 2009 (11.6%; p<0.001) or 2010 (10.2%; p<0.001). While the number of admissions in 2011 was approximately twice that in 2009 or 2010, hospitalisation for respiratory disease in 2011 was three or more times greater than in 2009 or 2010. The overall number of hospitalisations peaked during the first 10 days, while the number of admissions for respiratory disease continued to increase for the first 20 days (figure 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Number of unscheduled admissions for all causes (A) and for respiratory disease (B) from 11 March to 9 May in 2009, 2010 and 2011, presented in 10-day bins.

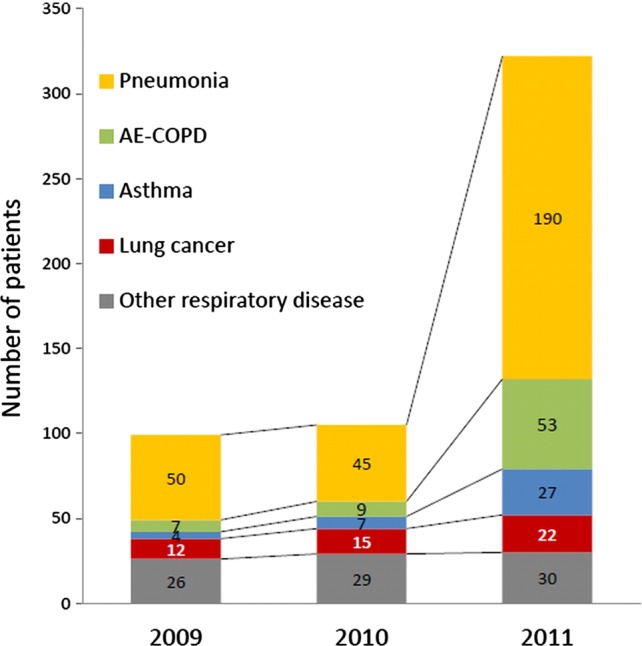

We compared the numbers and proportions of patients hospitalised for respiratory disease between 2011, 2010 and 2009 (figure 2). Pneumonia was the most frequent disease (n=190, 59.0%), followed by AE-COPD (n=53, 16.5%), asthma attacks (n=27, 8.4%) and progression of lung cancer (n=22, 6.8%). One case of AE-COPD and seven cases of asthma attacks were physician diagnoses. The category ‘others’ included pneumothorax, restrictive thoracic disease, pleural effusion, influenza, drowning, primary pulmonary hypertension, requirement for mechanical ventilation for neuromuscular disease, etc. One patient diagnosed with pneumonia who also had an asthma attack, and two patients with COPD exacerbated by pneumonia were treated for both conditions and counted as pneumonia. In comparison with the previous 2 years, the increase in the number of hospitalisations was greatest for pneumonia, followed by AE-COPD and asthma attacks. The numbers of hospitalisation for progression of lung cancer and for ‘others’ were similar to those in the previous 2 years. In 2011, 39.4% of patients were hospitalised from emergency shelters.

Figure 2.

Number and proportion of patients hospitalised for respiratory disease pooled from 11 March to 9 May in 2009, 2010 and 2011. AE-COPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

To investigate the disease-specific effect of the earthquake, the age and sex of each patient with a particular disease were compared between the study period in 2011 and the corresponding periods in the previous 2 years. The mean age of patients hospitalised for respiratory disease was significantly higher in 2011 than in the preceding 2 years (75.7±12.5 vs 73.2±13.4 years old; p=0.03). There were fewer males in 2011 compared to the previous 2 years (59.6% in 2011, 67.2% in 2010 and 2009; p=0.08). Specifically, pneumonia patients and AE-COPD patients were significantly older in 2011 compared to 2010 and 2009 (pneumonia patients were 77.6±11.8 vs 74.3±12.8 years old; p=0.03, while AE-COPD patients were 76.0±8.7 vs 69.5±15.9 years old; p=0.03). Significantly more males had AE-COPD (81.1% vs 50.0%; p=0.01), but significantly fewer had asthma attacks in 2011 compared with 2010 and 2009 (18.5% vs 54.6%; p=0.03).

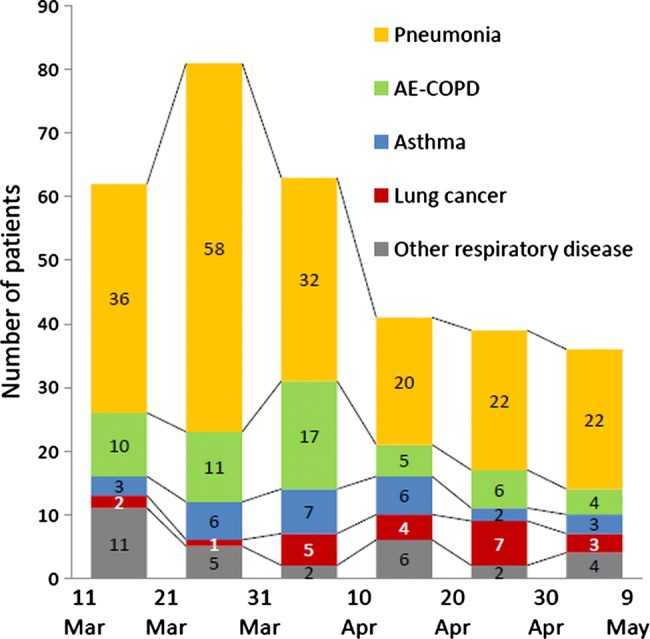

The numbers of admissions for the main respiratory diseases for each 10-day bin during the study period are shown in figure 3. Pneumonia peaked during the second 10-day bin, AE-COPD and asthma attacks peaked during the third 10-day bin and progression of lung cancer peaked in the fifth 10-day bin.

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients hospitalised for respiratory disease after the Great East Japan Earthquake from 11 March to 9 May in 2011, presented in 10-day bins. AE-COPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

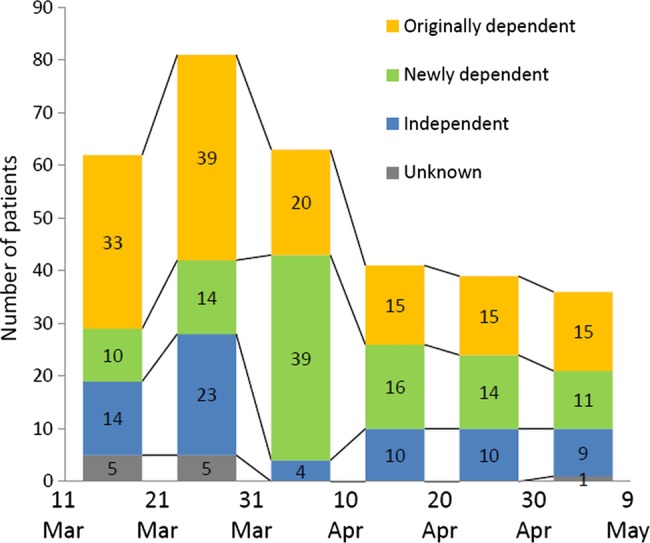

Next, we investigated ADL status at hospitalisation and before the disaster among patients admitted during the 2011 study period. Because of the confused situation after the disaster, ADL status was not recorded in 11 patients. At hospitalisation, 195 patients (60.5%) were ‘dependent’ and 54 patients (16.7%) were ‘partially dependent’. However, before the earthquake, only 86 patients (26.7%) were ‘dependent’ and 51 patients (15.8%) were ‘partially dependent’. To investigate the impact of ADL status and its deterioration on time of admission for pulmonary disease after the disaster, we counted the number of patients who were ‘originally dependent’, ‘newly dependent’ or ‘independent throughout’ in each of the 10-day bins (figure 4). Throughout the study period, the majority of patients were dependent or partially dependent. In the first 20 days, the majority of admissions were for ‘originally dependent’ patients. After 30 days, there was a sharp increase in ‘newly dependent’ patients, as assessed by ADL status. Independent patients were mainly hospitalised during the first 20 days. Table 1 shows the relationship between ADL category (‘independent throughout’, ‘newly dependent’ and ‘originally dependent’) and patient age, sex and diagnosis. The ratio of each disease was calculated for each category. Eleven patients whose ADL status was not completely recorded were excluded from the analysis. Young and male patients were more frequent in the order ‘independent’, ‘newly dependent’ and ‘originally dependent’. Patient diagnosis, proportion of pneumonia and progression of lung cancer increased in the same order, while the proportion of AE-COPD and asthma decreased.

Figure 4.

Influence of the disaster on activities of daily living status and its deterioration in patients hospitalised for respiratory disease from 11 March to 9 May in 2011, presented in 10-day bins.

Table 1.

Relationship between activities of daily living (ADL) and patient characteristics and respiratory disease

| Independent (n=70) | Newly dependent (n=104) | Originally dependent (n=137) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.9±15.1 | 73.1±11.2 | 80.3±10.5 |

| Male | 49 (70.0) | 63 (60.6) | 69 (50.4) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Pneumonia | 31 (44.3) | 59 (56.7) | 94 (68.6) |

| AE-COPD | 17 (24.3) | 17 (16.4) | 15 (11.0) |

| Asthma | 11 (15.7) | 11 (10.6) | 5 (3.7) |

| Lung cancer | 3 (4.3) | 6 (5.8) | 12 (8.8) |

| Others | 8 (11.4) | 11 (8.0) | 11 (8.0) |

AE-COPD, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Data are mean±SD for numerical variables and number (%) for categorical variables.

Discussion

Summary

In this retrospective descriptive and cross-sectional study, we found a substantial increase in the proportion of elderly patients hospitalised for respiratory disease after the earthquake and tsunami. Pneumonia, AE-COPD and asthma attacks were more common after the earthquake. The mean age of patients hospitalised for respiratory disease was significantly higher than that in the corresponding periods in the previous 2 years. The majority of patients had poor ADL status and many experienced deterioration in ADL status after the earthquake.

Effect on respiratory disease

Previous reports on the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake showed an initial increase in patients with injury and a subsequent increase in patients with respiratory disease, especially pneumonia.11–13 Similarly, our observation showed a marked increase in pneumonia patients, although there was no initial increase in patients with serious injury as the majority of victims drowned and heavily injured patients were not usually transferred to hospital.

The epidemiology of respiratory disease varies depending on the situation. For instance, after the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake and subsequent tsunami, the number of lower respiratory infections in Ache rapidly increased and then sharply declined during the second week.14 However, after the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake, the number of patients hospitalised for pneumonia increased gradually and remained high for over 2 months9 10 as pneumonia develops more slowly. In the Sumatra-Andaman earthquake, many cases of pneumonia resulted from aspiration of tsunami-water in near-drowning events (‘tsunami lung’).15 16 On the other hand, in the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake, numerous, mostly elderly patients staying in the unhealthy conditions of shelters developed pneumonia (‘shelter pneumonia’).17 In this earthquake and tsunami, we experienced few cases of pneumonia directly caused by aspiration of tsunami-water. A few patients came from the field, but most were from shelters, their own or relative's homes, other hospitals or nursing homes. Their mean age was significantly higher than in 2009 or 2010. Therefore, we regarded most of the pneumonia treated as ‘shelter pneumonia’. We were unable to carry out bacteriological tests for 14 days after the earthquake due to a shortage of water, fuel and manpower. Most pneumonias were considered ‘aspiration pneumonia acquired in a nursing home’ because of the patients’ ADL status.

Cases of AE-COPD were also significantly increased. COPD was one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases, especially in the elderly. It is well known that interruption of treatment for chronic disease frequently exacerbates the patient's condition, as after a natural disaster.14 18–20 Many patients lost their drugs in the tsunami, and therefore disruption of regular medication may partly account for the increase in AE-COPD admissions. Also, the weather was sunny and windy from the end of March and dust from the tsunami sludge was an important component of particulate air pollution and may have contributed to the significant rise in the number of admissions for AE-COPD.

Although asthma was also a common chronic respiratory disease and had the same precipitating cause as COPD, asthma attacks did not increase as much as AE-COPD, perhaps because of two important differences between the two conditions. First, COPD patients were generally older than those with asthma and so the baseline health status of COPD patients was poorer than that of those with asthma.21 As a result, COPD patients required more frequent hospitalisation. In our study, the mean age of AE-COPD patients was higher than that of those experiencing asthma attacks. Second, bacterial respiratory infection affects patients with COPD more than those with asthma.22 In the aftermath of the earthquake, poorer hygiene and overcrowding in shelters would have increased the risk of respiratory bacterial infection resulting in AE-COPD.

Hospitalisation for lung cancer related symptoms increased only slightly and actually declined as a proportion of total admissions for respiratory diseases. The mean age of lung cancer patients was similar to that in the previous 2 years. Maeda et al23 also reported that no increase in lung cancer related hospitalisation was observed after the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake. As lung cancer progression may be influenced less by the environment than by growth of the cancer, the disaster would not impact on lung cancer immediately. Although the interruption of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy would have worsened prognosis, this cannot be confirmed during our study period.

Effect on ADL status

In the acute phase following the disaster, patients with poor ADL status, especially those ‘originally dependent’, were hospitalised for pulmonary diseases, typically pneumonia, although substantial numbers of patients with good ADL status were also hospitalised. After 3 weeks, there was a sharp increase in ‘newly dependent’ patients whose ADL status had deteriorated. It was reported that physical disability was an independent risk factor for death in the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake and the 1999 Taiwan earthquake.9 10 However, those reports investigated mortality in the acute phase, not hospitalisation in the subacute or chronic phases. After the earthquake and tsunami, one in four Ishinomaki residents moved into shelters, many of which were also flooded by the tsunami. They lacked water and food and lived in unheated and overcrowded conditions, with many sleeping on the floor. As a result, the elderly had restricted consumption of food and water, and kept still in a small space, resulting in deterioration in their ADL status. In addition, scarcity of water worsened oral hygiene. Poor functional status and loss of oral hygiene were the major risk factor for pneumonia,24–27 especially in the elderly, many of whom were subsequently hospitalised for ‘shelter pneumonia’. Also, poor oral hygiene induces swallowing dysfunction28 which could be a risk factor for COPD exacerbation29 and may explain why AE-COPD increased especially in the elderly.

Effect on an aging society

According to the report of the Japanese government, in the Great East Japan earthquake 93% of deaths occurred as a result of drowning and over 60% of these victims were over 60 years of age. Many previous studies have noted that the elderly are at greater risk of death after earthquakes; however, the proportion of elderly people killed in this earthquake and tsunami was extremely high compared to other similar disasters.4–8 Comparable findings were reported only for 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake and the 2004 mid-Niigata earthquake, both in Japan.12 17 Moreover, 90.8% of patients hospitalised for respiratory disease after the earthquake in our study were over 60 years of age. These results suggest that the elderly are vulnerable immediately and also for a while after earthquakes.

In the 1999 Taiwan earthquake, the 2003 heat waves in the Czech Republic, and the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake, subsequent decreased mortality in the affected areas was the result of the large number of direct deaths caused by the disasters among vulnerable populations such as the elderly or children,5 30 31 the so-called ‘harvesting effect’. However, our observation suggests that, in an aging society, a disaster not only directly kills the vulnerable but also produces a new vulnerable population. Previous reports demonstrated that a prolonged harmful effect on mental health and slow psychological recovery were seen more frequently in the elderly than in young people.32–35 Therefore, we should provide long-term care to the elderly after a disaster.

Implications for policy and practice

Our observations suggest two important targets for reducing hospitalisation for respiratory disease after a major disaster in an aging society: interrupted chronic respiratory disease treatment and deterioration in ADL status. Interruption of treatment for chronic respiratory disease could be prevented if a few days’ stored drug supply were available. This would necessitate a storage system containing regional prescription data for each drug and personal medication data. Telemedicine systems or web-based patient data storage systems might be useful. Prevention of deterioration in ADL status is also important. Elderly people are potentially vulnerable and their ADL status can easily deteriorate. In our study, living in shelters for more than 3 weeks resulted in deterioration in ADL status and hospitalisation for respiratory diseases. Therefore, we propose that the elderly should be evacuated from disaster areas as quickly as possible.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

Our study has two important strengths. First, the Great East Japan Earthquake affected one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world.3 As the proportion of elderly people continues to increase in both developed and developing countries, there is an urgent need for information on and analysis of aging societies. The findings of our study are applicable to natural disasters worldwide. Secondly, we were able to obtain detailed information on patient demographics, diagnosis and ADL status in a catastrophic situation. This was because our hospital continued to function and maintained its electronic medical record systems and laboratory systems, despite a devastating earthquake and tsunami which severely affected most other medical facilities, and because staff in our hospital had received earthquake training and had recorded our experiences as memos or on digital recorders for analysis for disaster medicine.

Our study was conducted in a single centre. This might be a weakness of our study, but our hospital was the only functional hospital after the disaster in the Ishinomaki medical zone which experienced over 30% of the total fatalities in this earthquake. Also, it was the only hospital in the medical zone with a department of respiratory medicine and pulmonary specialists, and previously had accepted most seriously ill patients with pulmonary disease who needed hospitalisation. Therefore, we think our study accurately describes the impact of the earthquake on pulmonary diseases and explains what happened in a hospital directly affected by the earthquake.2 However, it is also weakness of our study that we only analysed hospitalised patients as there were also numerous outpatients, many of whom died. These events will be analysed in a future report. Another weakness is that a cross-sectional study cannot elucidate a causal relationship. Finally, we did not clearly define conditions for hospitalisation. Because of the destruction of the normal healthcare system and poor hygiene outside the hospital, we admitted some patients who normally would have been treated in an outpatient setting. However, this was a real situation after a devastating disaster.

Conclusion

The Great East Japan earthquake and subsequent tsunami affected one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world. After the disaster, pneumonia, COPD exacerbation and asthma attacks associated with low ADL status in the elderly significantly contributed to the increase in hospitalisation for pulmonary diseases. These observations should be used when planning emergency medical management for disasters in a progressive but rapidly aging society.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the relief teams and volunteers from Japan and abroad for their help and support. We also thank the doctors, nurses and other employees in Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: SY was responsible for study design and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. MH, SK, HS, ST and MY were responsible for the collection and interpretation of the data. KN drafted the statistical analysis section of the manuscript, and provided suggestions on public health and epidemiology. MH, SK and MY were responsible for study design and revised the draft manuscript. SY, MH, SK, HS, ST and MY treated the patients. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The ethics review committee of Japanese Red Cross Ishinomaki Hospital approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.McCurry J. Japan: the aftermath. Lancet 2011;377:1061–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Police Agency Damage situation and police countermeasures. http://www.npa.go.jp/archive/keibi/biki/index_e.htm (accessed 29 Dec 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamiya N, Noguchi H, Nishi A, et al. Population ageing and wellbeing: lessons from Japan's long-term care insurance policy. Lancet 2011;378:1183–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang NJ, Shih YT, Shih FY, et al. Disaster epidemiology and medical response in the Chi-Chi earthquake in Taiwan. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:549–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan CC, Lin YP, Chen HH, et al. A population-based study on the immediate and prolonged effects of the 1999 Taiwan earthquake on mortality. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13:502–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishikiori N, Abe T, Costa DG, et al. Who died as a result of the tsunami? Risk factors of mortality among internally displaced persons in Sri Lanka: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Public Health 2006;6:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rofi A, Doocy S, Robinson C. Tsunami mortality and displacement in Aceh province, Indonesia. Disasters 2006;30:340–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doocy S, Rofi A, Moodie C, et al. Tsunami mortality in Aceh Province, Indonesia. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:273–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou YJ, Huang N, Lee CH, et al. Who is at risk of death in an earthquake? Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:688–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osaki Y, Minowa M. Factors associated with earthquake deaths in the great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake, 1995. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:153–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takakura R, Himeno S, Kanayama Y, et al. Follow-up after the Hanshin-Awaji earthquake: diverse influences on pneumonia, bronchial asthma, peptic ulcer and diabetes mellitus. Intern Med 1997;36:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka H, Oda J, Iwai A, et al. Morbidity and mortality of hospitalized patients after the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake. Am J Emerg Med 1999;17:186–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuoka T, Yoshioka T, Oda J, et al. The impact of a catastrophic earthquake on morbidity rates for various illnesses. Public Health 2000;114:249–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guha-Sapir D, van Panhuis WG. Health impact of the 2004 Andaman Nicobar earthquake and tsunami in Indonesia. Prehosp Disaster Med 2009;24:493–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chierakul W, Winothai W, Wattanawaitunechai C, et al. Melioidosis in 6 tsunami survivors in southern Thailand. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:982–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potera C. In disaster's wake: tsunami lung. Environ Health Perspect 2005;113:A734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanida N. What happened to elderly people in the great Hanshin earthquake. BMJ 1996;313:1133–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guha-Sapir D, van Panhuis WG, Lagoutte J. Short communication: patterns of chronic and acute diseases after natural disasters—a study from the International Committee of the Red Cross field hospital in Banda Aceh after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Trop Med Int Health 2007;12:1338–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller AC, Arquilla B. Chronic diseases and natural hazards: impact of disasters on diabetic, renal, and cardiac patients. Prehosp Disaster Med 2008;23:185–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomita K, Hasegawa Y, Watanabe M, et al. The Totton-Ken Seibu earthquake and exacerbation of asthma in adults. J Med Invest 2005;52:80–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soriano JB, Davis KJ, Coleman B, et al. The proportional Venn diagram of obstructive lung disease: two approximations from the United States and the United Kingdom. Chest 2003;124:474–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pauwels RA. Similarities and differences in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2004;1:73–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda H, Nakagawa M, Yokoyama M. Hospital admissions for respiratory diseases in the aftermath of the great Hanshin earthquake(Article in Japanese). Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi 1996;34:164–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, et al. Microbiology of severe aspiration pneumonia in institutionalized elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:1650–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loeb MB, Becker M, Eady A, et al. Interventions to prevent aspiration pneumonia in older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1018–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langmore SE, Skarupski KA, Park PS, et al. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia in nursing home residents. Dysphagia 2002;17:298–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terpenning MS, Taylor GW, Lopatin DE, et al. Aspiration pneumonia: dental and oral risk factors in an older veteran population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:557–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshino A, Ebihara T, Ebihara S, et al. Daily oral care and risk factors for pneumonia among elderly nursing home patients. JAMA 2001;286:2235–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi S, Kubo H, Yanai M. Impairment of swallowing in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishikiori N, Abe T, Costa DG, et al. Timing of mortality among internally displaced persons due to the tsunami in Sri Lanka: cross sectional household survey. BMJ 2006;332:334–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kysely J, Kriz B. Decreased impacts of the 2003 heat waves on mortality in the Czech Republic: an improved response? Int J Biometeorol 2008;52:733–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyabe S, Shioiri T, Kuwabara H, et al. Impaired psychological recovery in the elderly after the Niigata-Chuetsu Earthquake in Japan: a population-based study. BMC Public Health 2006;6:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seplaki CL, Goldman N, Weinstein M, et al. Before and after the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake: traumatic events and depressive symptoms in an older population. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:3121–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ueki A, Morita Y, Miyoshi K. Changes in symptoms after the great Hanshin Earthquake in patients with dementia(Article in Japanese). Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 1996;33:573–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maeda K, Kakigi T. Manifestation of the symptoms in demented patients after the Great Hanshin Earthquake in Japan(Article in Japanese). Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 1996;98:320–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.