Abstract

Objectives

To assess how long the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence's (NICE) Technology Appraisal Programme has taken to produce guidance and to determine independent predictors of time to guidance.

Design

Retrospective time to event (survival) analysis.

Setting

Technology Appraisal guidance produced by NICE.

Datasource

All appraisals referred to NICE by February 2010 were included, except those referred prior to 2001 and a number that were suspended.

Outcome measure

Duration from the start of an appraisal (when the scope document was released) until publication of guidance.

Results

Single Technology Appraisals (STAs) were published significantly faster than Multiple Technology Appraisals (MTAs) with median durations of 48.0 (IQR; 44.3–75.4) and 74.0 (IQR; 60.9–114.0) weeks, respectively (p <0.0001). Median time to publication exceeded published process timelines, even after adjusting for appeals. Results from the modelling suggest that STAs published guidance significantly faster than MTAs after adjusting for other covariates (by 36.2 weeks (95% CI −46.05 to −26.42 weeks)) and that appeals against provisional guidance significantly increased the time to publication (by 42.83 weeks (95% CI 35.50 to 50.17 weeks)). There was no evidence that STAs of cancer-related technologies took longer to complete compared with STAs of other technologies after adjusting for potentially confounding variables and only weak evidence suggesting that the time to produce guidance is increasing each year (by 1.40 weeks (95% CI −0.35 to 2.94 weeks)).

Conclusions

The results from this study suggest that the STA process has resulted in significantly faster guidance compared with the MTA process irrespective of the topic, but that these gains are lost if appeals are made against provisional guidance. While NICE processes continue to evolve over time, a trade-off might be that decisions take longer but at present there is no evidence of a significant increase in duration.

Keywords: Health Economics, Public Health, Statistics & Research Methods

Article summary.

Article focus

How long have National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence's Technology Appraisals taken to produce guidance?

What features of an appraisal independently predict the time to publication of guidance?

Key messages

The Single Technology Appraisal (STA) process has reduced the time to publication by about 36 weeks irrespective of the topic.

Appeals against final appraisal determinations have more than doubled the time it takes for STAs to conclude. No other factors were strongly predictive of the time to guidance.

No variables predicting the likelihood of an appeal were identified.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Use of time to event analysis is a significant improvement upon previous studies addressing the primary question.

Other factors might also independently predict the time to guidance, such as consideration of patient access schemes and the number of consultees on each appraisal.

Introduction

In England and Wales, the primary role of National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence's (NICE's) Centre for Health Technology Evaluation is to produce guidance on the appropriate use of technologies for the National Health Service (NHS). Prior to 2005 all appraisals were undertaken using its Multiple Technology Appraisal (MTA) process.1 However, following criticism of the slow production of guidance,2 3 NICE established the Single Technology Appraisal (STA) process in 2005 with the objective of producing faster guidance closer to the time of product launch.4 5 Both processes produce determinations intended to guide decisions on technology adoption. Both respond to the challenge of uncertainty which already exists (but has not previously been addressed) or which has been produced by the arrival of a novel technology or new evidence. MTAs and STAs are largely identical in structure (but not scheduling) with the exception of the subprocess which assesses the evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The substantive differences therein are first, the party responsible for the assessment, and second, the scope of the analysis. In MTA, independent reviewers produce a comparative analysis of technologies for an indication and manufacturers also submit assessments. However in STAs, manufacturers’ submissions are limited to the consideration of a single technology and the independent review is restricted to a critique of this submission. Precise details of both processes can be found elsewhere;1 6 STA adoption has been rapid, increasing from 13% of all technology appraisals in June 2008 to 43.4% by February 2010.

STAs and MTAs should in theory take 43 and 60 weeks, respectively, to conclude in the absence of an appeal against the provisional guidance (more formally known as a ‘final appraisal determination’). A number of studies have attempted to assess whether the processes have met these targets and whether the STA process has resulted in faster guidance.7–9 For example, Ford et al8 suggest that the STA has reduced the time to produce guidance, but not for cancer-related technologies. O'Neill et al9 also suggest that the STA has reduced the average time to guidance, by approximately 1 year. However, both analyses are limited. First, Ford considers the time from product launch to guidance, rather than choosing a starting point on or after the point at which NICE assumes full control, and that is the date on which NICE is formally requested to appraise a technology by the Department of Health. NICE has only limited influence on the request date from the Department of Health. Second, the studies only include completed appraisals; no adjustments were made for ongoing, and potentially lengthy, assessments. This means that the results could be biased. Third, while Ford and O'Neill attempted to identify independent predictors of the time to guidance, none assessed these using formal statistical approaches for time to event data. Finally, no attempts were made to formally identify the individual contribution of each explanatory variable to the total time. The purpose of this study is to address all of these issues.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

All appraisals referred to NICE by February 2010 were considered for inclusion. However, MTAs prior to 2001 were excluded as they followed a different process to recent MTAs. Appraisals were also excluded (19 STAs and 7 MTAs) if they had been suspended or postponed following initial referral from the Department of Health but before NICE issued the final scope document.

Key dates, durations and data sources

Data for the analysis were taken from NICE's website. A small amount of missing data (comprised of 21 start dates, 6 suspension dates, 4 appeal announcement dates and 6 process types, ie, MTA or STA) was provided directly by NICE, on request. The ‘core’ appraisal time period was bounded as follows. Start dates were calculated for the majority of appraisals using the ‘final scope’ date, as this was the earliest consistently recorded time point available throughout the whole dataset. This date is also in line with when NICE ‘starts the clock’. The scope documents issued include information on the intervention(s) to be evaluated and the relevant comparator programmes. The time of scope document release can be viewed as a formal appraisal start date for the purposes of inviting and constructing evidenced based submissions. Where this date was unknown (for 1 STA and 6 MTAs), the start date was inferred using the ‘closing date for submissions to appraisal process by consultees’. This time point is scheduled to occur at week 9 in the STA process or week 14 for a MTA. Subtraction of the relevant number of weeks (9 or 14) allowed the start of the core process to be inferred.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using time to event (survival) analysis techniques with the ‘event’ being publication of guidance. Time to publication was initially assessed using Kaplan-Meier (KM) techniques, stratified by the parameter of interest (eg, STA/MTA process). Statistical significance was estimated using the log-rank test. The end (censor) date was taken to be the date final guidance was published, the date an appraisal was suspended or 13 February 2010 (the end of the data collection period), whichever occurred first. Rather than using Cox proportional hazard models to adjust KM results for multiple independent parameters, parametric techniques were instead used. This was because the latter is able to generate predictions of time to publication of guidance for censored events, and to provide direct estimations of the independent contribution of each predictive variable to the total time to guidance (ie, the marginal effect). For example, the number of weeks an appeal has added to the length of a MTA or STA can be calculated, all other factors held constant. A number of different parametric time to event models were fitted to the data including exponential, Weibull, lognormal, loglogistic, Gompertz and γ. The model that minimised Akaike's information criterion was selected for use. Sensitivity analysis was also used to assess the effect of using alternative parametric model forms. Additionally, logistic regression was used to assess whether a number of independent variables predicted the likelihood of an appeal. The proportion of appraisals completing within anticipated process times (43 and 60 weeks for STAs and MTAs) were assessed by assuming a binomial distribution. All analyses were undertaken using STATA V.12.

Choice of independent variables

The choice of appraisal process (STA or MTA) was an obvious parameter for inclusion, since STAs are designed to be shorter than MTAs. Other parameters were identified using the existing literature and consideration of the underlying processes. For example, it is logical that an appeal against provisional guidance could add substantially to the time it takes to publish final guidance. Other authors have also suggested that cancer appraisals are typically more complex and ‘controversial’, given that they tend to be associated with high incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, meaning they take longer to complete. NICE considers revising published appraisal guidance every 1–3 years. Given that in theory such revisions should be adding to an existing evidence base, it was suspected that these might take a shorter time to complete compared with other appraisals. O'Neill suggested that there was no evidence that appraisals are generally taking longer to complete, a so called ‘time-trend’. However, O'Neill also suggests that this conclusion should be revisited using more formal statistical approaches.

For these reasons, the following independent variables were included in the time to event analysis and logistic regression analysis: review of an existing appraisal (yes/no), drug (yes/no), cancer-related topic (yes/no), whether an appeal on the final appraisal determination (yes/no), calendar year of appraisal start (2001–2010) and an interaction term between STA and cancer to test whether there was a difference between cancer-related and remaining STAs.

Other parameters were considered for inclusion, some of which had previously been studied. These included consideration of patient access schemes, guidance that ultimately restricted the use of a technology and the number of groups (consultees) who were formally engaged with an appraisal. However, such parameters were rejected from the final model because of difficulties in consistently collecting this evidence. For example, a number of patient access schemes have been submitted to NICE, but only more recently has this become a formal part of NICE's appraisal processes.

The basic tested hypothesis was that none of the parameters independently predicted the time to publication of guidance.

Results

Data were collected on 196 appraisals, 80 STAs and 116 MTAs that started between 2001 and 2010 (table 1). All but one STA appraised the use of drugs, and almost 40% of all appraisals were cancer related. Approximately half of the STAs had been published (39/80) by the time of analysis, as had 84% (97/116) of the MTAs. Over 20% (45/196) of the appraisals included at least one appeal and 15% (29/196) were reviews of existing guidance.

Table 1.

Appraisals included in the analysis (n =196)

| Variable | STA | MTA |

|---|---|---|

| N | 80 | 116 |

| Guidance published* | 39 | 97 |

| Appraisal suspended* | 8 | 14 |

| Appraisal of a drug or drugs | 79 | 73 |

| Appraisal cancer-related | 47 | 29 |

| At least one appeal† | 9 | 36 |

| Review | 3 | 26 |

*At the time the analysis was undertaken.

†Appeals are made by consultees (often the producer of the technology) against final appraisal determinations, that is, NICE's provisional guidance.

MTA, Multiple Technology Appraisal; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; STA, Single Technology Appraisal.

The estimates of process length for completed STAs (published on time: 9/39=23%, p = 0.001) and MTAs (19/97=20%, p<0.001) exceeded NICE's timetabled targets of 43 and 60 weeks, respectively, with the corresponding median times of 45.4 (IQR 43.3–55.9) and 69.6 weeks (IQR 60.9–111.1). The proportion of appraisals from both processes continued to exceed published timelines after removing appraisals containing appeals (p <0.01 in both instances), although the median times were much closer to target levels (STA median 44.8 weeks, IQR 42.3–48.0; MTA median 61.6 weeks, IQR 57.7–71.1).

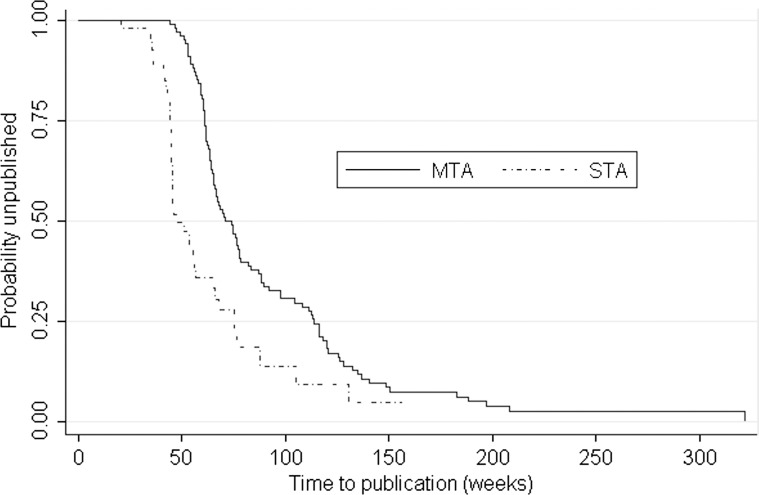

Results from the KM analysis showed that production of guidance was significantly faster for STAs than for MTAs; the median time to guidance was 48.0 weeks (IQR 44.3–75.4) and 74 weeks (IQR; 60.9–114.0) for the STA and MTA processes, respectively, (p value<0.0001, figure 1). Further stratified analysis (table 2) suggested that appeals significantly extended the time to guidance for both MTAs and STAs (p <0.001), and that cancer-related STAs were significantly longer compared with non-cancer STAs (p=0.02). None of the remaining comparisons were statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier time to event estimate of time to publication of guidance.

Table 2.

Results of Kaplan-Meier analysis (weeks), log-rank tests of equality of survivor functions

| MTA, n=116 |

STA, n=80 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strata | N | Median (IQR) | p Value | N | Median (IQR) | p Value |

| Cancer | 23 | 66.5 (60.6–111.1) | 18 | 57.0 (42.3–87.9) | ||

| No cancer | 74 | 74.0 (61.4–116.1) | 0.43 | 21 | 45.4 (44.7–55.7) | 0.02 |

| Review | 17 | 68.4 (61.4–111.1) | 1 | 44.1 (N/A) | ||

| Non-review | 80 | 74.0 (60.9–116.4) | 0.65 | 38 | 51.0 (44.7–75.4) | 0.18 |

| Drug | 59 | 77.6 (62.4–116.3) | 39 | 48.0 (44.3–75.4) | ||

| Non-drug | 38 | 66.6 (57.7–91.8) | 0.11 | 0 | N/A | - |

| Appeal* | 35 | 116.1 (91.9–136.9) | 7 | 76.7 (65.0–105.3) | ||

| No appeal | 62 | 61.6 (57.7–71.1) | <0.001 | 32 | 44.9 (42.3–48.0) | <0.001 |

*Indicates at least one appeal.

MTA, Multiple Technology Appraisal; N indicates observed events; N/A, not applicable; STA, Single Technology Appraisal.

Results from the multivariate parametric modelling suggested that the loglogistic model was the most appropriate to use. STA and appeals were shown to be associated with faster and slower times to guidance, respectively, (table 3). None of the remaining variables were significantly associated with the time to guidance although there was weak evidence of a yearly increase in the time it has taken to publish guidance (1.40 weeks (95% CI −0.35 to 2.94 weeks)). Sensitivity analysis using different distributional forms had negligible effects on the results. None of the covariates were found to be predictive of the likelihood of an appeal (data not shown).

Table 3.

Results from the loglogistic modelling

| Variable | Coefficient | 95% CI | p Value | Marginal effect (weeks)‡ | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STA* | −0.49 | −0.62 to −0.36 | <0.001 | −36.2 | −46.05 to −26.42 |

| Cancer* | −0.03 | −0.002 to 0.04 | 0.60 | −2.06 | −9.80 to 5.70 |

| STA × cancer | 0.13 | −0.05 to 0.30 | 0.15 | 9.23 | −3.36 to 21.81 |

| Drug* | 0.08 | −0.01 to 0.20 | 0.08 | 6.10 | −0.75 to 12.87 |

| Review* | −0.04 | −0.12 to 0.07 | 0.43 | −3.26 | −11.39 to 4.87 |

| Ever an appeal* | 0.60 | 0.50 to 0.67 | <0.001 | 42.83 | 35.50 to 50.17 |

| Year started† | 0.02 | −0.002 to 0.04 | 0.073 | 1.40 | −0.35 to 2.94 |

| Ln_γ | −2.06 | −2.20 to −1.91 | <0.001 | − | − |

Log likelihood=2.23; constant=4.04.

*Yes=1, no=0.

†Where values range between (200)1 and (20)10.

‡Indicates the independent contribution to the median to time to publication; values less than 0 indicate that variables are associated with a shorter time to guidance.

Discussion

The results from this analysis show that NICE's STA process produced much faster guidance to the NHS compared with the MTA process, by about 36 weeks. But appeals against provisional guidance, when they occurred, more than offset this gain. The results from the KM analysis suggested that cancer-related STAs were longer than non-cancer STAs. However, the difference was no longer statistically significant when adjustments were made for other variables. The evidence that each year appraisal length is independently increasing is weak at best (increase of 1.40 weeks (95% CI −0.35 to 2.94 weeks)). Variables indicating whether a technology was a drug or a review of existing guidance were not predictive of the time to guidance.

How does this compare with other studies?

The percentages of MTAs and STAs completing within timetabled targets are consistent with those reported by O'Neill et al.9 While the estimates of STA duration were also similar, the time taken to produce MTAs was not; O'Neill and colleagues stated an average duration of about 100 weeks whereas our unadjusted estimate was nearer to 74 weeks indicating a much smaller difference between the two process types. It is possible that methodological differences could explain these findings. For example, MTAs appraise the use of more than one technology. O'Neill considered each technology within a MTA to represent a discrete decision, thus an appraisal with three recommendations was effectively taken to be equivalent to three appraisals. In this study each appraisal was taken to represent a single event irrespective of the number of recommendations it contained. However, irrespective of the best approach, it should be noted that NICE clearly states published timelines represent a minimum amount of time to publication and that the median times were within 2 weeks of target levels when appraisals containing appeals were removed from our analysis.

O'Neill et al9 reported that STAs were substantially faster than MTAs. The unadjusted analysis of Ford et al8 also suggests that STAs have reduced the time to guidance compared with MTAs, but not for STAs of cancer-related technologies. We agree with the general finding that the STA has significantly reduced the time to guidance. However, while our unadjusted KM analysis also suggests STAs of cancer-related technologies were slower to complete compared with their non-cancer related counterparts, the difference was no longer significant when adjustments were made for other variables, including appeals.

Both O'Neill and Ford include analyses that estimate the time between product launch and production of guidance by NICE, presumably because a specific objective of the STA process is to minimise this time period. However, our analysis used the point at which NICE issued its final scope as the appraisal starting point. We elected not to use the time of product launch for a number of reasons. First, the date is difficult to measure accurately and specifically, as there is no readily available source of indication-specific license dates. Second, the time from product launch to start of the NICE process is largely outside of NICE's control. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the duration derived from the use of the launch date often has little meaning. For example, guidance on the use of vinorelbine for advanced breast cancer (TA 54)10 was published in 2002, whereas its marketing authorisation was issued in 1997, 2 years before NICE existed.

O'Neill et al cautiously stated that there was no evidence that either the STA or MTA have increased in length over time. We agree with this conclusion.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this analysis compared with previous studies is that it uses formal time to event analysis techniques to assess the time to publication of guidance. In doing so, adjustments are made for potentially confounding variables and estimates of the marginal contribution of each variable to the total time are generated. This said, there are a number of limitations. First, the start of each appraisal was taken to be the time at which consultees are formally invited to submit evidence, set as the time at which the final scope document is issued. An alternative viewpoint could be that since NICE consults on scope documents, appraisals in some senses start about 3 months earlier, even though there is no guarantee during the consultation that the appraisal will proceed. While including this extra time would increase the median time to guidance, it is unlikely to alter the predictive value of the explanatory variables. Second, no account was taken of interruptions that were outside of NICE's control, such as public holidays or publication embargos during general elections; the latter can be lengthy. Third, MTAs usually result in guidance that relates to the use of more than one technology. In this analysis all appraisals have been treated as equal, in so much that no account has been made of the number of technologies being appraised. However, it is conceivable that one MTA of (say) three technologies could be shorter, in terms of calendar time, than three separate STAs. This could mean that comparisons of the two processes should be treated with some caution. Fourth, there is a potential issue of endogeneity in the statistical analysis since it is possible that appeals are at least partly a result of the other independent variables. While this cannot be completely ruled out, none of the examined variables were independently predictive of an appeal, thus we think this issue is unlikely to be important. Lastly, although it is likely that other variables may be related to the time to guidance, there are challenges in quantifying them. One such example is the number or mix of consultees, which could reflect the complexity/level of interest in a particular area. We could not find a reliable method of quantifying this potential predictor of time to guidance; patient groups often produce joint submissions, and only the product manufacturer is officially a consultee in a STA.

It has also been suggested that the scale of the evidence base could act as a predictor of duration. However, the conceptual nature of any such relationship is not clear. One hypothesis could be that where there exists only a small number of trials, the time to guidance would be shorter. However, Ford et al8 suggest an alternative hypothesis. They suggest that a limited evidence base can produce uncertainties in cost-effectiveness data, causing problems in setting start/stop prescribing rules. Such a ‘challenge to the appraisal committee’ could result in a request for further information and consequential delays, that is, increased time to guidance. The question of whether such an association exists would be best answered using a range of qualitative and quantitative methods and goes beyond the scope of this study.

Concerns have previously been raised about the variable quality of manufacturer submissions to the STA process5 and cost-effectiveness estimates generated by manufacturers are often more favourable than those provided by independent academic groups.11 This analysis says nothing about the quality of submissions. But we would suggest that any potential short comings with the STA process are not necessarily confined to the independence of the health technology assessment (HTA) dossier; rather they are arguably equally or more likely to reflect restricted scopes, in terms of comparator technologies, and the relative immaturity of the evidence base, as STAs are increasingly aligned with a product's launch. Whether or not this is true, there remains an important debate to be had about the speed of HTA production, the potential trade-off in terms of comprehensiveness of the compiled evidence base, and whether policy recommendations are materially affected.

Conclusion and recommendation

In summary, the evidence suggests that despite the incorporation of more detailed methods and processes over the past decade, the time it has taken NICE to produce guidance over the past decade has not independently increased. The introduction of the STA process has resulted in the production of significantly faster guidance to the NHS, irrespective of the clinical topic. However, appeals when they occur can significantly extend this time. We therefore recommend that where possible, efforts be made to develop working practices and processes which can reduce the need for such appeals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Nina Pinwill, Associate Director at NICE, advised on appraisal processes and the selection of time points suitable for analysis. Pinwill also provided the missing data described in the text.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM conceived the idea of the study; SC and AM were responsible for its design. SC collected, processed and analysed the data initially. SC and AM undertook the subsequent analysis and produced the tables and graph. SC, AM and FR contributed to the interpretation of the results. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by SC and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. All authors approved the final version of the paper to be published. AM is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. It was conducted as part of an MSc degree at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The BMJ Open publication fee has been paid by LSHTM.

Competing interests: SC has no relationship with NICE. AM is a current member of one of NICE's Technology Appraisal Committee's and its Technology Appraisals’ Decision Support Unit. FR is a member of NICE International, a not-for-profit consultancy service within NICE. FR, SC and AM have no other non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of any associated organisation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guide to the multiple technology appraisal process. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayor S. NICE to issue faster guidance to the NHS. BMJ 2005;331:110116282390 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haycox A. Does ‘NICE blight’ exist, and if so, why?. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:987–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NICE Guide to the single technology appraisal process. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wailoo A, Pickstone C. A review of the NICE Single Technology Appraisal process. Sheffield: School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield (Decision Support Unit), 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guide to the single technology appraisal process. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barham L. Single Technology Appraisals by NICE—are they delivering faster guidance to the NHS? Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:1037–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford JA, Waugh N, Sharma P, et al. NICE guidance: a comparative study of the introduction of the single technology appraisal process and comparison with guidance from Scottish Medicines Consortium. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Neill P, Devlin N, Puig-Peiro R. Time trends in NICE HTA decisions. In: OHE Consulting report. London: Office of Health Economics, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guidance on the use of vinorelbine for the treatment of advanced breast cancer. Technology Appraisal Guidance 2002 01/01/2012); http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA54 (accessed 3 Jan 2012).

- 11.Miners AH, Garau M, Fidan D, et al. Comparing estimates of cost effectiveness submitted to the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) by different organisations: retrospective study. BMJ 2005;330:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.