Abstract

Objective

To examine the prevalence of key WHO breastfeeding indicators and identify determinants of suboptimal breastfeeding practices among children aged less than 24 months in Tanzania.

Design, setting and participants

Secondary analyses of cross-sectional data from the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey. The survey used a stratified two-stage cluster sample of 10 312 households from eight geographical zones of Tanzania. The sample consisted of 3112 children aged 0–23 months.

Main outcome measures

Outcome measures were factors significantly associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding, non-exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding in the first 6 months.

Results

Breastfeeding was initiated within the first hour of birth in 46.1% of mothers. In infants aged less than 6 months, the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was 49.9% but only 22.9% were exclusively breastfed at 4–5 months. Seventeen per cent of infants, less than 6 months of age, were ‘predominantly breastfed’. At 12–15 months, 94.0% of infants were still breastfed but the proportion decreased to 51.1% at 20–23 months of age. Multivariate analysis revealed that the risk of delayed initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h after birth was significantly higher among young mothers aged <24 years, uneducated and employed mothers from rural areas who delivered by caesarean section and those who delivered at home and were assisted by traditional birth attendants or relatives. The risk factors associated with non-exclusive breastfeeding, during the first 6 months, were lack of professional assistance at birth and residence in urban areas. The risk of predominant breastfeeding was significantly higher among infants from the Zanzibar geographical zone.

Conclusions

Early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding indicators were unsatisfactory and are below the national targets for Tanzania. To improve breastfeeding practices, national level programmes will be required, but with a focus on the target groups with suboptimal breastfeeding practices.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Determinants, Early initiation of breastfeeding, Exclusive breastfeeding, Predominant breastfeeding, Tanzania

Article summary.

Article focus

This paper aims to examine key WHO breastfeeding indicators in Tanzania and determine factors associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding, non-exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding practices in children aged 0–23 months.

Key messages

Prevalence of early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding indicators fell below national targets for Tanzania. A considerable proportion of infants less than 6 months were predominantly breastfed.

Children who live in the Northern, Southern zones and Zanzibar were at higher risk of sub-optimal\optimal breastfeeding practices than children in other geographical zones of Tanzania.

Young maternal age, lower maternal education, employment, home delivery and lack of professional assistance at birth were the main determinants of suboptimal breastfeeding practices in Tanzania.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main limitation was the cross-sectional nature of the survey, which limited inferences about causality from the analyses.

In addition, exclusive breastfeeding was based on a 24 h recall rather than a longer recall period, and this short recall may have missed some infants who were fed other liquids or foods prior to 24 h before the survey.

However, the use of a large nationally representative survey sample with a very high response rate (96.4%), appropriate statistical adjustments for survey design and modelling for confounding effects add strength to the validity of the findings. Furthermore, restricting the sample to only children less than 2 years who lived with their mothers helped ensure greater accuracy of information regarding breastfeeding practices.

Introduction

WHO1 infant-feeding guidelines recommend that all infants should be breastfed within 1 h after birth and exclusively breastfed from birth until 6 months of life. Thereafter, infants should be introduced to nutritionally adequate and safe complementary foods with continued breastfeeding for up to 2 years or beyond. In line with the WHO recommendations, Tanzania has been implementing a number of initiatives to improve infant-feeding practices, which include the National Strategy and Implementation Plan on Infant and Young Child Nutrition, the baby-friendly hospital initiatives and the training of health workers on infant-feeding skills. Despite these efforts, breastfeeding practices and especially early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding remain suboptimal in Tanzania.2

According to the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS) of 2010,2 breastfeeding was almost universal at 99% in all sociodemographic categories; however, early initiation of breastfeeding, within 1 h after birth, was reported by 46.1% of women who recently delivered a baby, whereas the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) was 50% among infants less than 6 months.2 This implies that a considerable proportion of infants aged less than 6 months are introduced to other liquids and solid foods before the recommended age of 6 months and thereby limit the full benefits of breastfeeding. Low adherence to optimal breastfeeding including exclusive breast feeding for the first 6 months and risk of diarrhoeal disease from contaminated complementary foods given to infants, well before 6 months of age, is believed to contribute to under nutrition observed in young children. For instance, the 2010 TDHS reported that 35% of children under-5 years of age were stunted while 21% were under weight indicating that undernutrition is a public health problem in Tanzania that needs to be addressed at a very early stage of infant's life.2

It is well established that optimal breastfeeding confers protective effects against gastrointestinal infections and improves child survival.3–5 A cohort study carried out in Ghana revealed that 22% of neonatal deaths could be prevented if all infants were put to the breast within the first hour of birth.4 It has also been reported that exclusive breastfeeding from birth and until 6 months of age has the potential to prevent 13% of all deaths among children, aged less than 5 years, annually in developing countries.6

Research investigating the factors associated with suboptimal breastfeeding practices has been conducted in developed and developing countries, including African countries, and shows that delayed initiation of breastfeeding after birth and not exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months were influenced by factors such as maternal age,7–9 maternal level of education,8–10 maternal employment status,10 11 maternal nutritional status,12 place of delivery,13 14 mode of delivery,15–17 area of residence,16 household wealth status10 and geographical differences.16 18 These factors have been documented to be either positively or negatively associated with breastfeeding practices, and the inconsistencies of the results found in different countries make it difficult to generalise the findings to all countries, hence the need to identify factors that are associated with breastfeeding practices in Tanzania.

This secondary data analysis of the 2010 TDHS aims to describe the prevalence of breastfeeding practices using the current WHO breastfeeding indicators,19 and to determine the factors associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding, non-exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding among children less than 24 months of age in Tanzania.

Methods

Data source

The present analysis was based on the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS),2 which was conducted from December 2009 to May 2010 by the National Bureau of Statistics and the Office of the Chief Government Statistician –Zanzibar in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. The 2010 TDHS is the eighth in a series of Demographic and Health Surveys conducted in Tanzania. The survey aimed to gather information about child mortality, nutrition, maternal and child health, as well as family planning and other reproductive health issues. The survey sample was designed to provide estimates for the entire country, for both urban and rural areas, which comprised of 26 regions from the Tanzania mainland and Zanzibar.

Survey design

The 2010 TDHS utilised a cross-sectional study design and a nationally representative survey sample was obtained using stratified two-stage random sampling.2 In the first stage, 475 clusters were selected from a list of enumeration areas from the 2002 Population and Housing Census.20 Eighteen clusters were selected in each region except Dar es Salaam, where 25 clusters were selected in the Mainland. In Zanzibar, 18 clusters were selected in each region for a total of 90 sample points. In the second stage, a complete household listing was carried out in each of the selected clusters. Twenty-two households were selected from each cluster in all regions except for Dar es Salaam where 16 households were systematically selected. A total of 10 300 households were selected for the sample, of which 10 176 were successfully interviewed, yielding a household response rate of 99%. From these households, 10 522 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) who were either permanent residents of the households in the 2010 TDHS sample or visitors present in the household on the night before the survey were interviewed. Face-to-face interviews were held with the sampled mothers using a structured questionnaire yielding an interview response rate of 96.4%. Comprehensive details regarding the sampling procedure and data collection tools are available in the 2010 TDHS report.2

Feeding indicators

There are fifteen indicators recommended by WHO19 21 for assessing infant and young child-feeding practices. The breastfeeding indicators reported in the survey include

‘Early initiation of breastfeeding: proportion of children born in the last 24 months who were put to the breast within 1 h of birth—this indicator is based on historical recall’.

‘Exclusive breastfeeding under 6 months: proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who were fed exclusively with breast milk—this indicator is based on mother's recall on feeds given to the infant on the previous day’,

‘Continued breastfeeding at 1 year: proportion of children 12–15 months of age who were fed breast milk’.

‘Continued breastfeeding at 2 years: proportion of children 20–23 months of age who were fed breast milk’.

‘Predominant breastfeeding: proportion of infants 0–5 months of age who were fed with breast milk from the mother (either directly or expressed) and certain liquids (water, water-based drinks and fruit juice) and ritual fluids. Infants who received non-human milk and food-based fluids were not included when computing the prevalence of this indicator’.

‘Children ever breastfed: proportion of children born in the last 24 months who were ever breastfed’.

‘Bottle feeding: proportion of children 0–23 months breastfeeding of age who are fed with a bottle’.

WHO recommends that the EBF indicator be disaggregated for the following age groups: 0–1, 2–3, 4–5 and 0–3 months. Ever breastfed and early initiation of indicators were further disaggregated and reported for live births occurring 0–12, 12–23 and 0–23 months prior to interview. It should be noted that the EBF indicator defined above does not represent the percentage of infants who are exclusively breastfed at 6 months of age19 22 but rather the average prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding of children <6 months of age.

The breastfeeding indicators were examined by the individual level factors, which included mother's age, mother's body mass index measured by weight (kg)/height (m2), mother's literacy, mother's working status, mother's education, mother's marital status, partner's education, partner's occupation, birth order, birth interval, sex of child, age of child, perceived size of the baby, place of delivery, type of delivery assistance, number of antenatal clinic visits, timing of postnatal check-up, mode of delivery, mother's access to mass media; household level factors included household wealth index and mother's autonomy in household decision-making, and community level factors included place of residence and geographical zones. The household wealth index was calculated as a score of household assets weighted using the principal components analysis method.23

Early initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h of birth and exclusive breastfeeding were examined in multivariate analysis because their prevalence continues to be below the national target and WHO/UNICEF recommendation of 90% coverage.24 25 Early initiation of breastfeeding and EBF also play a vital role in protecting infants against diarrhoeal diseases, and reducing mortality among many infants in developing countries.26 The rates of ‘ever-breastfed’ and ‘continued breastfeeding’ were very high (>90%); hence, they were not included in multivariate analysis. The indicator for predominant breastfeeding was also included in multivariate analysis owing to its impact on increasing the risk of diarrhoeal and respiratory illness in infants.26 In addition, bottle feeding was not considered in this analysis because the prevalence was very low (4%).

Data analysis

Our analysis was restricted to the alive, youngest, last-born infants aged less than 24 months, living with their mothers (women's age 15–49 years) during the 2010 TDHS and the total weighted sample was 3112. The analysis of determinants of early breastfeeding initiation was based on the entire sample (3112 children) whereas those of exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding were based on 837 infants aged from 0–5 months. Non-exclusive breastfeeding (non-EBF) was expressed as a dichotomous variable with category 1 for non-EBF and category 0 for EBF. Delayed initiation of breastfeeding was expressed as a dichotomous variable with category 0 for early initiation of breastfeeding and category 1 for delayed initiation of breastfeeding. Predominant breastfeeding was expressed as a dichotomous variable with category 1 for predominant breastfeeding and category 0 for non predominant breastfeeding. These variables were examined against a set of independent variables (individual, household and community characteristics) in order to determine the prevalence and factors associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding, non-exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding indicators.

Analyses were performed using Stata V10.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). ‘Svy’ commands were used to allow for adjustments for cluster sampling design, sampling weights and the calculation of standard errors. The Taylor series linearisation method was used to estimate CIs around prevalence estimates. A χ2 test was used to test the significance of associations. Unadjusted and adjusted ORs (AOR) were calculated to estimate the strength of association between independent variables and three breastfeeding indicator outcomes: delayed initiation of breastfeeding, non-exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding. In our multivariate statistical modelling, we created an indicator variable for missing data and restricted our analysis to non-missing data. Multiple logistic regression using survey commands was conducted using stepwise backwards elimination of variables in order to determine the factors significantly associated with the outcome of breastfeeding indicators. The ORs with 95% CIs were calculated in order to assess the adjusted risk of independent variables, and only those with p<0.05 were retained in the final model. We did our backward stepwise model by adjusting for sampling weights and clusters. We double-checked our background elimination method by using the following procedure: (1) enter only variable with p value <0.20 in our backward elimination process; (2) tested backward elimination by also including all variables (all potential confounders) and (3) we tested for collinearity. The linear interpolation method was used to compute the median duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Note: in the present study, delayed initiation of breastfeeding refers to the proportion of children born in the last 24 months who were not put to the breast within 1 h of birth and non-exclusive breastfeeding refers to the proportion of infants aged 0–5 months who were not fed exclusively with breast milk.

Results

Basic characteristics of the sample

Online supplementary table S1 shows the distribution of 3112 children aged less than 24 months according to individual-, household-level, and community-level characteristics. The majority of children lived in rural areas (79.7%). Many mothers (67.0%) had primary level education, and about 86% were employed in the last 12 months. Eighty-five per cent of the mothers were currently married, and their husband's occupation was dominated by agricultural activities (63.5%). Of all children, more than half (50.9%) were born in health facilities but a relatively low percentage of mothers delivered by caesarean section (5.1%). Most mothers (48.0%) were assisted by health professionals at delivery, and a high proportion of mothers were multiparous (80.4%). About 48% of mothers had made at least three antenatal clinic visits during pregnancy, and 31.4% had postnatal check-ups 41 days after birth. The gender of the children was nearly equally represented in the sample. Approximately one-quarter (22.6%) of the children were from poor families.

Breastfeeding indicators

Less than half of the mothers (46.1%) had initiated breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, whereas 98.5% reported they had ‘ever breastfed’ their infants (table 1). 49.9% of infants less than 6 months of age were exclusively breastfed, but the median duration for exclusive breastfeeding was only 2.6 months. Less than a quarter (16.8%) of infants below 6 months of age were predominantly breastfed. About 94% of the children were still breastfed at 12–15 months but the percentage decreased to 51.1% at 20–23 months of age. A few children (3.8%) were bottle-fed from birth to 23 months.

Table 1.

Prevalence of breastfeeding indicators among children aged less than 24 months in Tanzania

| Indicator | Size of subsample (weighted) | n (weighted) | Rate (%) | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early initiation of breastfeeding 0–23 months | 3112 | 1434 | 46.1 | (43.44 to 48.76) |

| Early initiation of breastfeeding 0–11 months | 1630 | 750 | 46.0 | (42.58 to 49.45) |

| Early initiation of breastfeeding 12–23 months | 1482 | 685 | 46.2 | (43.00 to 49.43) |

| Children ever breastfed 0–23 months | 3112 | 3065 | 98.5 | (97.68 to 99.00) |

| Children ever breastfed 0–11 months | 1630 | 1604 | 98.4 | (97.31 to 99.07) |

| Children ever breastfed 12–23 months | 1482 | 1461 | 98.6 | (97.63 to 99.11) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding 0–5 months | 837 | 418 | 49.9 | (45.65 to 54.15) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding 0–1 months | 245 | 197 | 80.7 | (74.13 to 85.94) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding 2–3 months | 299 | 153 | 51.1 | (44.38 to 57.80) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding 4–5 months | 293 | 67 | 22.9 | (17.69 to 29.10) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding 0–3 months | 544 | 350 | 64.4 | (58.82 to 69.66) |

| Predominant breastfeeding 0–5 months | 837 | 141 | 16.8 | (13.46 to 20.74) |

| Continued breastfeeding at 1 year | 524 | 492 | 94.0 | (91.02 to 96.09) |

| Continued breastfeeding at 2 years | 419 | 214 | 51.1 | (45.19 to 57.04) |

| Bottle feeding 0–23 months | 3112 | 200 | 3.8 | (2.97 to 4.97) |

| Bottle feeding 0–5 months | 837 | 39 | 4.7 | (3.06 to 7.17) |

| Bottle feeding 6–11 months | 793 | 43 | 5.4 | (3.75 to 7.73) |

| Bottle feeding 12–23 months | 1482 | 37 | 2.5 | (1.66 to 3.83) |

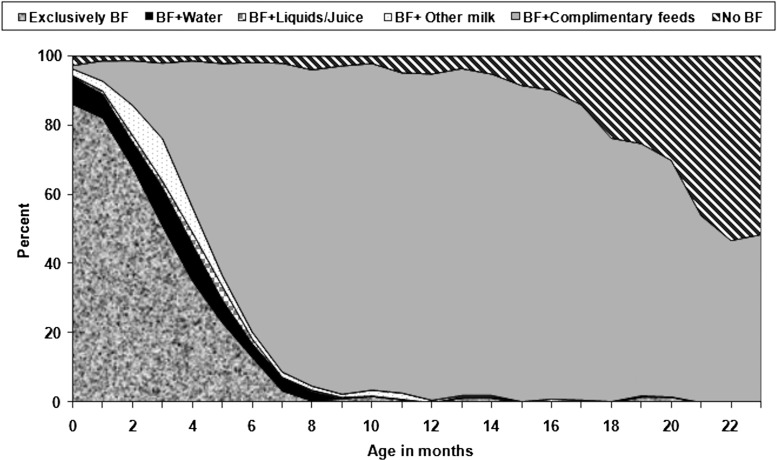

As shown in figure 1, prevalence of EBF was more than 86% at birth but declined rapidly with age to 23.1% at 6 months. At birth, 10.8% of infants were given breast milk plus other fluids, including water, juices or other milk.

Figure 1.

Distribution of children by breastfeeding status according to age.

Breastfeeding indicators across individual-level, household-level, and community-level characteristics

As seen in online supplementary table S3, early initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth was significantly lower among mothers who delivered at home (34%); those who were not assisted by health professionals (32.7%); residing in rural areas (42.2%); those from poorest households (39.3%) and living in the Eastern zone (36.5%) and the Northern zone (39.3%). There was a significantly lower prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding among mothers who delivered by caesarean section (20.9%); those who did not have any postnatal check-ups (42.7%); mothers who did not have any autonomy in decision making (43.1%); mothers who were unable to read (38.9%) and those with poor access to mass media including radio (41.5%) and television (44.1%). In contrast, there was a higher prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h of birth among mothers from the richest households (62.9%); from the Central (52.1%), Southern Highland (53.0%) and the Western (51.4%) geographical zones; from urban areas (61.2%); who delivered at health facilities (57.7%); who were married to a husband not involved in agricultural activities (54.9%), and those who had a higher level of education (62.7%) and their partners had secondary and higher level of education (62%).

Exclusive breastfeeding of infants aged less than 6 months of age was significantly lower among mothers who had worked in the last 12 months (48.0%); mothers who resided in urban areas (40.3%); those from the richest households (37.0%) and those living in Zanzibar (10.4%). The proportion of infants who were exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life were observed to be higher among mothers from rural areas (52.2%) and those living in the Eastern (52.2%), Western (53.6%) and Southern (51.6%) geographical zones. The rates of predominant breastfeeding were not significantly different across individual-level, household-level and community-level factors.

Determinants of breastfeeding indicators

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs were calculated to estimate the effect of independent variables on three infant-feeding outcomes: delayed initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, non-exclusive breastfeeding and predominant breastfeeding. As seen in online supplementary table S4, the adjusted odds of delayed initiation of breastfeeding were significantly higher among infants whose mothers were aged less than 24 years, had a low level of education (no education/primary education), worked in the last 12 months, delivered their babies at home with assistance from an untrained provider (traditional birth attendants or relatives/other people) and those who were delivered by caesarean section. The odds of delayed initiation of breastfeeding were also higher for infants from rural compared with infants from urban areas. As compared with infants from the Western geographical zone, infants from Lake, Northern, Eastern and Zanzibar were at a higher risk of delayed initiation of breastfeeding within an hour after birth.

The odds of non-EBF were significantly higher in infants whose mothers were assisted by traditional birth attendants (TBA) at birth than infants of mothers who were assisted by health professionals. When type of delivery assistant was removed from the final model and replaced by place of delivery, we found that place of delivery was not significantly associated with non-EBF. Hence, type of delivery assistance was retained in the final model. The risk of non-EBF was also significantly higher for urban infants compared with their rural counterparts. As expected, increasing infant age was associated with significantly low rates of EBF. Infants from Zanzibar were at greater risk of non-EBF and predominant breastfeeding compared with infants from other geographical zones.

Discussion

This study found that less than half of the mothers had initiated breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, and that only half of the mothers exclusively breastfed their infants aged less than 6 months. Seventeen per cent of infants less than 6 months of age were predominately breastfed. We found that lower maternal education, younger maternal age, being employed, delivered at home, delivered by caesarian section, delivery assistance by untrained provider and residing in rural areas of Eastern, Lake, Northern and Zanzibar were determinants of delays in initiation of breastfeeding within first hour after birth. Similarly, delivery assistance by an untrained provider and residing in urban areas of Zanzibar were predictors of non-exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of infant's life. We have also identified the target groups of women who need more breastfeeding support that included young, uneducated, employed women <25 years, women from both rural and urban areas in the Eastern, Lake, Northern and Zanzibar geographical zones and women who also lacked proper care during and after birth.

This paper is one of the few reports from Africa, including Tanzania, which has described the prevalence of breastfeeding practices using the most recent nationally representative data from Tanzania, and the current WHO-recommended definitions for assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding indicators. The findings from this study will help guide health programmes to improve early initiation of breastfeeding, and exclusive breastfeeding in order to ensure young children in Tanzania receive the full benefits of appropriate breastfeeding practices including reduced morbidity and mortality.

The main strengths of this study include the use of a large nationally representative survey sample, with very high response rate to the survey interviews (96.4%), comprehensive data on standard infant-feeding indicators to identify factors associated with suboptimal breastfeeding practices in Tanzania, and appropriate sampling design in the analysis. Furthermore, we restricted the sample for children to only those who lived with their mothers to ensure greater accuracy of information regarding breastfeeding practices. The main limitation was the cross-sectional nature of the survey which limited inferences about causality from the analyses. In addition, EBF was based on a 24 h recall rather than a longer recall period, and this short recall may have missed some infants who were fed other liquids or foods prior to 24 h before the survey.

The prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding has declined from 59% in 200527 to 46% in 2010, highlighting the need to reverse this trend and to increase the percentage of initiating breastfeeding within 1 h of birth. Similarly, the prevalence of EBF in Tanzania was very low in comparison with other neighbouring African countries such as Uganda (60%),28 Zambia (61%)29 and Malawi (57%).30 A considerable proportion (17%) of infants less than 6 months were predominantly breastfed, suggesting a need for counselling mothers, caregivers and key family members on the risks associated with predominant feeding. This strategy would help to change their behaviour which ultimately improved EBF. In our analysis, we found a significant association between maternal young age (15–24 years) and delayed initiation of breastfeeding. This result is consistent with findings from India which showed that older mothers (≥35 years) were at lower risk of delayed initiation of breastfeeding compared with young mothers (AOR for older mothers ≥ 35 years= 0.72, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.02).13 We further explored this association with parity and found that most of the young mothers in Tanzania were first-time mothers, suggesting that they lacked knowledge or experience about appropriate breastfeeding practices. Hence, the need for health professionals and traditional birth attendants to provide adequate support to encourage young and first-time mothers to establish early initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h after giving birth.

Similar to the findings reported in India,13 we also found that women with higher levels of education had a reduced risk of delayed initiation of breastfeeding and this might be explained by their exposure to various sources of information and better knowledge about appropriate infant and young child feeding. The variations in the prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding across different geographical zones could be due to cultural differences and taboos about breastfeeding newborns with first breast milk (ie, colostrum) in different regions of Tanzania.31–33 A major concern is the very low prevalence of EBF in Lake and Zanzibar geographical zones. This could be due to inadequate knowledge among mothers and family members regarding benefits of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of infant's life and also existence of belief that breast milk alone is not sufficient to fulfil infant's hunger hence complement with other liquids/soft foods.31 Provision of adequate support and educating mothers and their families from these zones on the importance of giving initial breast milk to infants and EBF until 6 months may have a positive effect on improving rates of early initiation of breastfeeding and EBF and potentially reduce the risks of infections and death among newborns.4

In this study, rural infants had significantly higher risk of delayed initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h after birth compared with urban infants. This finding is in agreement with the previous studies from the Morogoro region in Tanzania31 and from Ethiopia.34 The difference in early initiation of breast feeding between rural and urban mothers might be explained by the high percentage of rural women who delivered at home (93%) assisted by TBAs and other people such as family members. These birth attendants may have had inadequate knowledge of the benefits of this feeding practise and thus failed to support mothers in initiating breastfeeding early. Furthermore, negative cultural beliefs about colostrum and lower level of education among rural mothers (88%) might also have contributed. Rural women may need more support to overcome barriers to early initiation of especially those living in the Eastern, Lake, Northern and Zanzibar geographical zones. On the other hand, mothers from urban areas were at greater risk of poor EBF practices than mothers from rural areas, possibly because of the demand to return to work after maternity leave11 since most of these urban mothers were in paid employment. Also, most mothers in urban areas were from families with higher socioeconomic status compared with rural areas and that may have facilitated access to breast milk substitutes. For example, data from a multilevel analysis of factors associated with non-EBF in nine East and Southeast Asian countries revealed that improved socioeconomic status both at individual levels and community levels was a negative factor for EBF.9

The risk of delayed initiation of breastfeeding in the first hour after birth was significantly higher among mothers who delivered at home compared with those who delivered at health facilities. Similarly, having a baby not delivered by a health professional was a significant predictor of non-EBF. This indicates the need to educate key family members and TBAs about the benefits of initial breast milk for the newborn so that they can encourage mothers who deliver at home to establish breast-feeding immediately after birth and EBF up to 6 months. Exclusive breastfeeding should also be promoted at health facilities during antenatal care visits and during deliveries; and at the community level through peer counselling support for EBF.35

Delivery by caesarean section was a risk factor for delayed initiation of breastfeeding in Tanzania. This finding is consistent with previous reports from India,13 Nepal36 and Sri Lanka.37 This association may be linked to the effects of anaesthesia delaying the onset of lactation and some baby-unfriendly postoperative-care practices.38 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies that examined influence of caesarean delivered on early breastfeeding showed that caesarean delivery has a significant adverse association with early breastfeeding.17 Appropriate guidelines for caesarean deliveries are needed to minimise delays in initiation of breastfeeding. Prospective mothers and health workers should be informed about the negative association between prelabour caesarean delivery and breastfeeding and the implications for infant well-being.17

Our analysis showed a negative association between maternal working status and early initiation of breastfeeding 1 h after birth. However, our subanalysis to examine the relationship between maternal working status and area of residence found that, most working mothers (68.6%) resided in rural areas than in urban areas (12.5%), and they had higher risk of delayed initiation of breastfeeding within 1 h after birth, as discussed earlier. We also found that the prevalence of EBF decreased with increasing age of the child. This finding was in conformity with other secondary analyses of demographic and health surveys conducted in Nigeria,18 India,13 Bangladesh,39 Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines and Timor-Leste, and Vietnam9 and Malawi14 which have also reported a declining prevalence of EBF as the age of the child increased.

Conclusions

The prevalence of breastfeeding indicators regarding early initiation of breastfeeding and EBF were below the nationaltargets (90% coverage)40 and improvement is needed, for infants, to gain the full benefits of breastfeeding and help the country achieve the Millennium Development Goal for reduction of infant mortality from 51 deaths per 1000 births in 2010 to 38 deaths per 1000 live births by the year 2015.2 The improvement of breastfeeding practices will require national level programmes with a focus on target groups with suboptimal breastfeeding practices including young, uneducated mothers who deliver at home assisted by untrained health personnel, and those who deliver by caesarean section. Further research is recommended to investigate why early initiation of breastfeeding is decreasing in Tanzania.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Australian Agency for International Development for sponsoring the MPhil fellowship for RV.

Footnotes

Contributors: RV designed the study, performed the analysis and prepared the manuscript; SKB provided advice on study design, and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content; KEA provided advice on study design, data-analysis and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content; and MJD provided advice on study design and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The ethics approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Appendices to the extended report are available in English.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (Tanzania) and ICF Macro Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. NBS and ICF Macro. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO collaborative study team on the role of breastfeeding on the revention of infant mortality Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries. A pooled analysis. Lancet 2000;355:451–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmond K, Zandoh C, Quigley MA, et al. Delay breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics 2006;117:e380–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edmond KM, Kirkwood BR, Amega-Etego S, et al. Effect of early infant feeding practices on infection-specific neonatal mortality: ana investigation of causal links with observational data from Ghana. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1126–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, et al. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 2003;362:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melina T, Maria S, Antonis G, et al. Breastfeeding in Athens, Greece: factors associated with its initiation and duration. J Ped Gastr Nutr 2006;43:379–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lande B, Andersen LF, Baerug A, et al. Infant feeding practices and associated factors in the first six months of life: the Norwegian infant nutrition survey. Acta Paediatr 2003;92:152–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senarath U, Dibley MJ, Agho KE. Factors associated with nonexclusive breastfeeding in 5 East and Southeast Asian countries: a multilevel analysis. J Hum Lact 2010;26:248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amir L, Donath S. Socioeconomic status and rates of breastfeeding in Australia: evidence from three recent national health surveys. Med J Aust 2008;189:254–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakati A, Binns C, Stevenson M. The effect of work status on exclusive breastfeeding in Nairobi. Asia Pac J Public Health 2001;14:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Smith MG, Dobre MA, et al. Maternal obesity and breastfeeding practices among white and black women. Obesity 2009;18:175–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel A, Badhoniya N, Khadse S, et al. Infant and young child feeding indicators and determinants of poor feeding practices in India: secondary data analysis of National Family Health Survey 2005–06. Food Nutr Bull 2010;31:314–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaahtera M, Kulmala T, Hietanen A, et al. Breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices in rural Malawi. Acta Paediatr 2001;90:328–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauck YL, Fenwick J, Dhaliwal SS, et al. A Western Australian survey of breastfeeding initiation, prevalence and early cessation patterns. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:260–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dibley MJ, Roy SK, Senarath U, et al. Across-country comparisons of selected infant and young child feeding indicators and associated factors in four South Asian countries. Food Nutr Bull 2010;31:366–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prior E, Santhakumaran S, Gale C, et al. Breastfeeding after caesarean delivery:a systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:1113–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agho KE, Dibley MJ, Odiase JI, et al. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:2–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Part I: Definitions. Conclusion of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington, DC, USA, 2008

- 20.National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Tanzania 2002-population and housing census.Dar es Salaam; 2002, General Report [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Part 3 Country Profile. Geneva: WHO Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agampodi SB, Agampodi TC, Silva A. Exclusive breastfeeding in Sri Lanka: problems of interpretation of reported rates. Int Breastfeed J 2009;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gwatkin DR, Rutstein S, Johnson K, et al. Socioeconomic differences in health, nutrition and poverty. Washington, DC: HNP/Poverty Thematic Group of the World Bank, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre. Tanzania national strategy on infant and young child nutrition. Ministry of Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO/UNICEF Global action plan for prevention and control of pneumonia (GAPP). 2009. http://www.unicef.org/media/files/GAPP3_web.pdf (accessed 14 March 2012)

- 26.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, et al. Martenal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancent 2008;371:243–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Tanzania and ORC Macro Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2004–05. National Bureau of Statistics and ORC Macro Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) Macro International Inc Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Calverton, MD: UBOS and Macro International Inc, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Central Statistical Office (CSO), Ministry of Health (MOH), Macro International . Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Calverton, MD: CSO and Macro International Inc, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Statistical Office (NSO) and ORC Macro Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Calverton, MD: NSO and ORC Macro, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirima R, Greiner T, Kylberg E, et al. Exclusive breast-feeding is rarely practised in rural and urban Morogoro, Tanzania. Public Health Nutr 2001;4:147–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sellen DW. Infant and young child feeing practices among African pastoralist. J Biosoc Sci 1998;30:481–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agnasson I, Mpello A, GunnLaugsson G, et al. Infant feeding practices during the first six moths of life in a rural area of Tanzania. East Afr Med J 2001;4:9–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setegn T, Gerbaba M, Belachew T. Determinants of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers in Goba Woreda, South East Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tylleskar T, Jackson D, Meda N, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding promotion by peer counselors in sub-Saharan Africa (PROMISE-EBF): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:420–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandey S, Tiwari K, Senarath U, et al. Determinants of infant and young child feeding practices in Nepal: secondary data analysis of Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Food Nutr Bull 2010;31:334–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senarath U, Dibley MJ, Godakandage SSP, et al. Determinants of infant and young child feeding practices in Sri Lanka: secondary data analysis of Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Food Nutr Bull 2010;31:352–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathews MK. The relationship between maternal labour analgesia and delay in initiation of breastfeeding in healthy neonates in the early neonatal period. Midwifery 1989;5:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mihrshahi S, Kabir I, Roy SK, et al. Determinants of infant and young child feeding practices in Bangladesh: secondary data analysis of Demographic Health Survey 2004. Food Nutr Bull 2010;31:295–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ministry of Health Tanzania and Tanzania Food and Nutrition Centre. Tanzania national strategy on infanta and young child nutrition implementation plan. Ministry of Health, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2004:6 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.