Abstract

The Retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor protein regulates multiple pathways that influence cell growth, and as a key regulatory node, its function is inactivated in most cancer cells. In addition to its canonical roles in cell cycle control, RB functions as a global repressor of RNA polymerase (Pol) III transcription. Indeed, Pol III transcripts accumulate in cancer cells and their heightened levels are implicated in accelerated growth associated with RB dysfunction. Herein we review the mechanisms of RB repression for the different types of Pol III genes. For type 1 and type 2 genes, RB represses transcription through direct contacts with the core transcription machinery, notably Brf1-TFIIIB, and inhibits preinitiation complex formation and Pol III recruitment. A contrasting model for type 3 gene repression indicates that RB regulation involves stable and simultaneous promoter association by RB, the general transcription machinery including SNAPc, and Pol III, suggesting that RB may impede Pol III promoter escape or elongation. Interestingly, analysis of published genomic association data for RB and Pol III revealed added regulatory complexity for Pol III genes both during active growth and during arrested growth associated with quiescence and senescence.

Keywords: RNA polymerase III, Retinoblastoma, transcription, repression, chromatin, cell cycle

1. Introduction - The Retinoblastoma Tumor Suppressor Protein

Mutations in the RB1 gene, encoding the Retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor protein were originally identified as culpable in a rare childhood eye tumor known as Retinoblastoma [1]. In early studies of retinoblastoma cell lines, tumor-associated mutations were correlated with either undetectable RB1 mRNA or mRNA of a decreased molecular size [2, 3], consistent with the loss of RB expression in these pediatric tumors. Subsequently, RB1 mutations were observed in other classes of cancers, especially small-cell lung carcinomas [4], wherein genetic lesions at the RB1 locus are as penetrant as in retinoblastoma (reviewed in [5]). These early studies suggested an important role for RB in prevention of adult-onset malignancies, and indeed, dysregulation of the RB pathway via direct mutation of RB or through indirect modulation of other regulatory components is so frequently observed as to be recognized as a hallmark of cancer [6, 7].

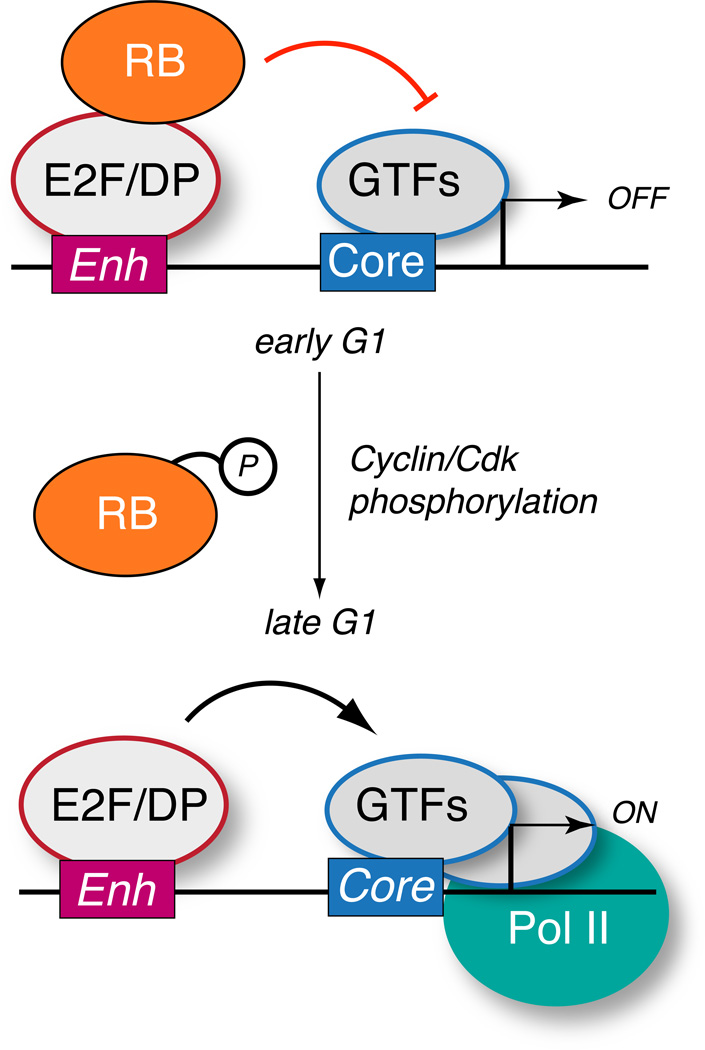

The function of RB in tumor suppression has been an actively pursued topic with early studies linking RB function to cell cycle control. RB is a 110 kDa protein which becomes phosphorylated when cells are rapidly cycling [8–11] and dephosphorylated in growth arrested cells [12]. Microinjection of recombinant RB into nocodazole-synchronized cells early in the G1 phase resulted in a pronounced G1 cell cycle block that was not observed when RB was injected in asynchronously growing cells [13]. These studies linked the changes in RB phosphorylation status to cell cycle control, a process centrally important to regulated proliferation. RB post-translational modification is facilitated by the cyclin dependent kinase (cdk) 4/ cyclin D and cdk2/cyclin E complexes, whose activities are important for G1 progression [14–16]. RB was found to associate with the E2F family of transcription factors and impede their function in RNA polymerase (Pol) II activation of cell cycle target genes [17–20]. A prevalent model emerged that RB prevents transcription of key genes required for DNA synthesis in early G1 and cyclin/cdk phosphorylation relieves RB repression (Figure 1). In addition to cell cycle control, RB is dephosphorylated as cells differentiate, implicating RB function in developmental processes [9]. RB also participates in regulation of apoptotic responses [21–23], and it is clear that RB governs multiple aspects of cell fate choices that are deregulated in tumorigenesis.

Figure 1. RB repression of cell cycle target genes is relieved by cyclin/cdk phosphorylation.

During early G1, RB can form stable complex at cell cycle target gene promoters through interactions with the E2F/DP transcriptional activator, interfering with transcriptional activation. Repression can be mediated via disruption of the general transcription factors (GTFs) or via recruitment of chromatin modifying factors. Later in G1, RB is phosphorylated by the cyclin D/cdk4 and cyclin E/cdk2 kinases to disrupt E2F interaction and relieve repression.

2. RNA polymerase III activity in cancer – The biosynthetic capacity hypothesis

The prevalent model for RB function in attenuating cancer progression attributes RB mutation with the loss of E2F repression and cell cycle control. However, this cell cycle-centric model does not account for a simple requirement that accelerated proliferation by cancer cells must also involve increased synthesis of cellular components to match their increased rate of division. In part, the requisite increased biosynthetic capacity for rapid proliferation is achieved by increased output by Pol III, which is responsible for the production of the 5S ribosomal (r) RNAs, all transfer (t) RNAs, and a multitude of other non-protein coding RNAs [24], many of which are involved in protein output (reviewed in [25, 26]. Many of these well established genes and some newly identified loci have been recently characterized as bona fide Pol III targets in mammalian cells in genomic ChIP-seq experiments [27–29] that further revealed a surprising complexity to Pol III regulation and function.

Consistent with their essential role in active growth, Pol III transcripts are frequently elevated in tumor cells [30–33], and many of these same cells exhibit defects in the RB pathway. Indeed, the RB tumor suppressor was shown to repress global Pol III transcription both in vitro and in vivo [34]. From these early studies, a biosynthetic capacity hypothesis was proposed that Pol III inhibition by tumor suppressors, including RB, limits cellular proliferation [34, 35]. Supporting the concept that Pol III activity is limiting to robust cancer proliferation, the forced reduction of Pol III activity in mouse xenograft assays could inhibit tumor formation [36]. An integral connection between enhanced Pol III activity and cellular dysfunction in human cancer is also suggested from the observation that scleroderma patients who exhibit autoantibodies against Pol III also are more likely to be diagnosed with some forms of cancer than similar patients who don’t express elevated Pol III antibodies [37]. These observations hint that Pol III levels or activity may be a prelude to clinically evident disease in a subset of cancer patients. Pol III-associated structures and activity may also serve as useful biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and disease staging as some Pol III transcripts are localized to nuclear structures termed perinucleolar compartments (PNC) [38], and increased PNC prevalence has been positively correlated with tumor progression and poor prognosis for patient survival [39–43]. While the function of the PNC remains enigmatic, these observations provide support of the hypothesis that increased steady state levels of Pol III transcripts are an important contributing factor in cancer progression.

3. RNA Polymerase III transcription during cell cycle progression

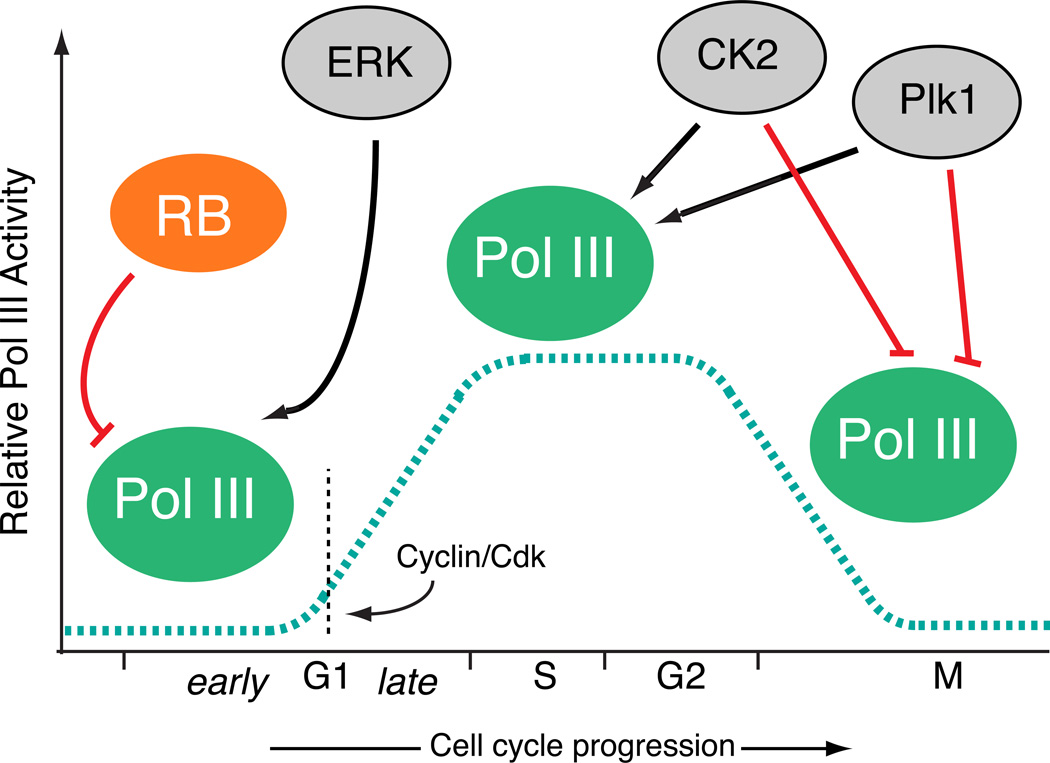

The products of Pol III target genes play essential roles in cell growth, and consequently they are often maintained at very high levels during periods of active proliferation. Many of these RNAs exhibit long half lives, and the combination of high steady state levels and long half lives has often lead to the assumption that these “housekeeping genes” are constitutively active. However, it has become clear that Pol III transcription is dynamically regulated both during development and throughout the cell cycle (Figure 2). The highest levels of Pol III activity are typically observed in late G1, S, and G2 phases and lowest levels prevalent during early G1 and M phases [44–48], as determined using extracts prepared from staged cells. While global Pol III activity fluctuates during the cell cycle, Pol III target genes exhibit distinct factor requirements, and its activity at specific loci is governed by stage-specific and gene-specific mechanisms, dependent upon underlying promoter structures, as described in more detail below.

Figure 2. Pol III activity is dynamically regulated during cell cycle progression.

During G0 and early G1, Pol III transcription is repressed by RB and its related family members, p107 and p130. Upon RB phosphorylation by cyclin/cdk, Pol III activity increases until peak activity is achieved during late G1 and S phases. In some contexts, Pol III activity increases in early G1 after serum stimulation via Ras activation and ERK stimulation of Brf1-TFIIIB in a process that precedes cyclin/cdk activation. The protein kinase CK2 and Polo-like kinase both exhibit positive and negative effects on Pol III transcription, stimulating activity in S phase but inhibiting activity during mitosis. The mechanism for Pol III regulation by each of these factors is different for the distinct types of Pol III genes, as dictated by underlying differences in promoter architecture and factors involved.

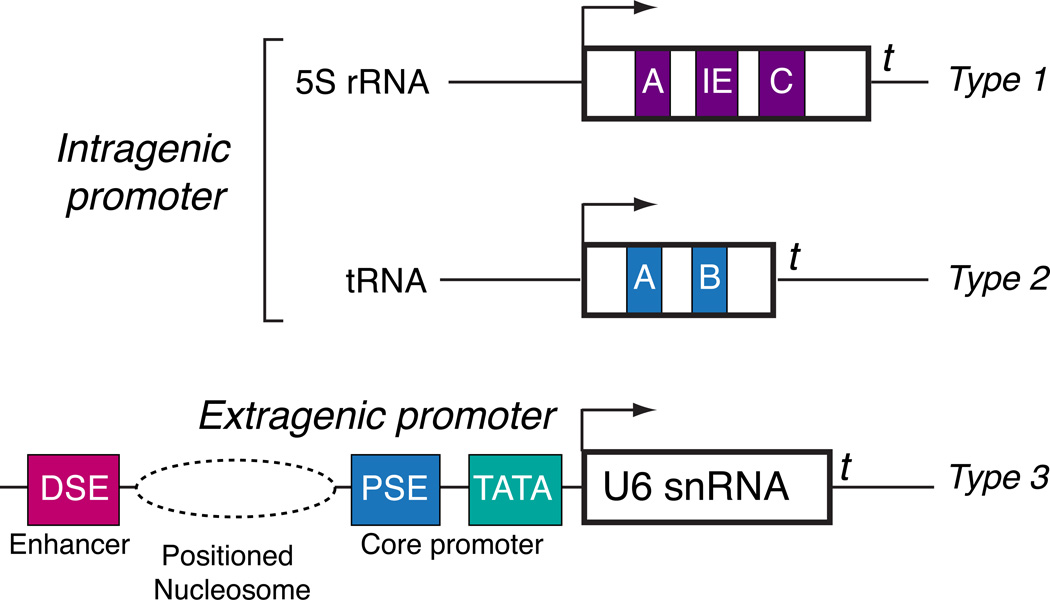

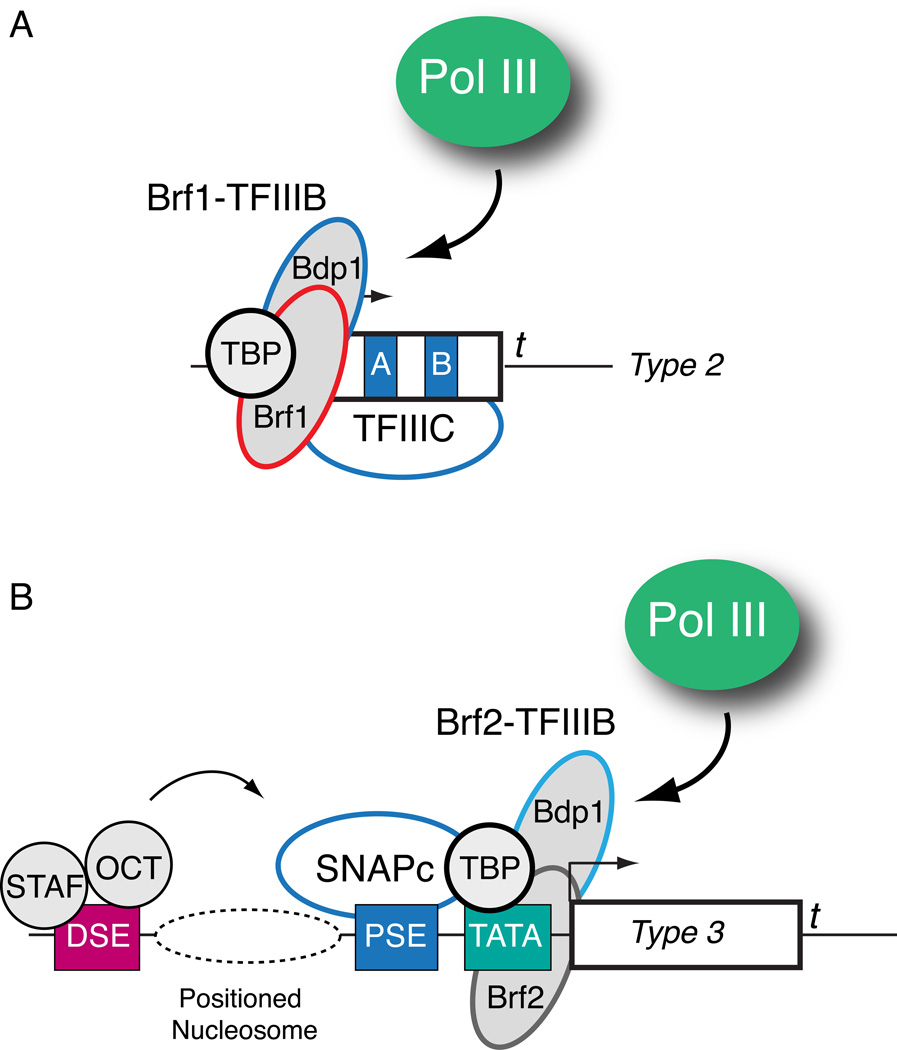

Pol III transcribed genes are grouped into three general types (Figure 3). Both type 1 (5S rRNA) and type 2 (tRNA) Pol III responsive genes contain intragenic promoter elements that recruit TFIIIA plus TFIIIC, or just TFIIIC, respectively (reviewed in [25, 26]). In both types, promoter recognition is followed by recruitment of the Brf1-TFIIIB complex, composed of the TATA box binding protein (TBP) [49–52], Brf1 [53–57], and Bdp1 [56, 58–60]. In contrast, Type 3 genes contain extragenic promoter elements, and promoter recognition is accomplished by a multiprotein complex called the small nuclear RNA activating protein complex (SNAPc) [61–66], also known as the PSE transcription factor (PTF) [67–70]. SNAPc cooperates for promoter recognition with a related but different TFIIIB complex that contains TBP and Bdp1, but Brf2 instead of Brf1 [56, 57, 71, 72]. Pol III is directly recruited by TFIIIB complexes [50, 73–75], and these complexes have emerged as the preeminent signaling nexus governing Pol III activity (Figure 4). Interestingly, both the protein kinase CK2 [48, 76–78] and the Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) [79] phosphorylate TFIIIB with both positive and negative roles in Pol III regulation, stimulating activity during interphase but inhibiting activity during mitosis. In both signaling pathways, TFIIIB phosphorylation disrupts Bdp1 chromatin association during mitosis with consequent diminished transcription [46, 80, 81]. One prediction is that CK2 can phosphorylate Bdp1 to affect global Pol III activity, while Plk1 phosphorylates Brf1 and affects only type 1 and 2 genes, providing regulatory flexibility within the Pol III network. CK2 can also phosphorylate SNAPc [82] and affect cooperative DNA binding by SNAPc and TBP [83, 84], but any contributions to type 3 gene regulation during cell cycle progression have not been established. In addition to regulated output during the S phase and M phase of the cell cycle, Pol III activity is generally low during early G1 phase. Interestingly, a robust increase in steady state B2 RNA levels was observed after serum stimulation [85], and this rapid elevation in endogenous B2 transcripts was sensitive to ERK kinase inhibition, linking increased Pol III output to the Ras pathway. Like the other kinase pathways described above, ERK can interact with and phosphorylate the Brf1 component of TFIIIB. However, the ERK docking site is absent in Brf2, suggesting that type 3 genes might respond differently to signaling through the Ras pathway

Figure 3. Pol III transcribes target genes with divergent promoter structures.

Both type 1 (5S rRNA) and type 2 (tRNA) genes exhibit intragenic promoter elements while type 3 genes contain extragenic promoter elements. Transcription from the U6-1 gene is stimulated by a nucleosome that is positioned between the enhancer and core promoter regions. In all cases, Pol III transcription is terminated at a string of thymidine residues (t).

Figure 4. Type 2 and type 3 genes utilize different but overlapping sets of factors for Pol III transcription.

(A) Schematic representation of the factors used for Pol III transcription from type 2 promoters. The A and B boxes within the intragenic promoter are recognized by the multiprotein TFIIIC complex. Promoter targeting of the Brf1-TFIIIB complex, composed of Br1, TBP, and Bdp1, is facilitated by communication between TFIIIC and Brf1-TFIIIB. The Bdp1 component of the Brf1-TFIIIB complex plays an important role in direct Pol III recruitment. (B) Schematic representation of the factors used for Pol III transcription from type 3 promoters. Core promoter recognition is accomplished by cooperative DNA binding by the multiprotein SNAP complex and a distinct Brf2-TFIIIB complex, composed of Brf2, TBP, and Bdp1. The juxtaposition of the PSE and TATA box dictates that these genes are transcribed by Pol III. DNA binding by SNAPc is also stimulated by the Oct-1 and STAF activator proteins with direct protein-protein contacts potentially enabled by DNA wrapping around a nucleosome positioned between the DSE and PSE.

4. Role of RB in RNA polymerase III transcription

Early observations suggested that Pol III activity is diminished in early G1 phase of the cell cycle, a period that correlates with increased RB activity [47, 86], and thus efforts were initiated to investigate the contribution of RB to Pol III regulation. From these pioneering studies, a clear role emerged for RB [34] and its related family members p107 and p130 [87]. The first report connecting RB regulation to Pol III transcription demonstrated that RB-deficient human Saos2 osteosarcoma cells support elevated Pol III transcription as compared to RBproficient U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Primary mouse fibroblasts deficient for RB also supported elevated Pol III transcription as compared to matched wild type MEFs in nuclear run-on assays, thus providing strong evidence that RB functions as a global repressor of Pol III activity in vivo [34]. Pol III transcription of an adenovirus VAI construct, a type 2 gene, could also be repressed by recombinant RB minimally containing the AB pocket and C-terminal domains. This observation was significant because previous studies on RB repression of E2F-mediated Pol II transcription demonstrated that these same regions were important for cell cycle control and tumor suppression [88–91]. In addition, the RB-related family members p107 and p130 were found to repress Pol III activity [87], and as these RB family members exhibit different activity profiles during cell cycle progression [92–94], these members might contribute to regulatory capability at distinct cell cycle stages [95] and in different tissue types.

A potential repression mechanism for type 1 and type 2 gene regulation, shown in Figure 5, was first established when it was observed that RB could co-purify with Brf1-TFIIIB, both in co-immunoprecipitation assays and in biochemical fractionation of Brf1-TFIIIB from transcriptionally active cell extracts [96, 97]. This connection had direct functional implications given the important role for the Brf1-TFIIIB complex in Pol III recruitment. Consistent with the notion that the RB-Brf1-TFIIIB connection is relevant, only the hypophosphorylated and active form of RB commonly observed in early G1 phase was found to associate with Brf1-TFIIIB [95]. In vitro, Brf1-TFIIIB activity became limiting upon RB addition to Pol III repression assays [96, 97], suggesting that this complex is the functional target for RB during repression. In addition to Brf1-TFIIIB, RB was observed to associate with both Brf1-TFIIIB and TFIIIC2 in one study [97], and a competitive equilibrium model of RB repression was proposed wherein RB disrupts communication between TFIIIC2 and Brf1-TFIIIB [97]. Both of these studies led to the model that RB represses Pol III transcription by disrupting key interactions among the basal transcription machinery [96, 97].

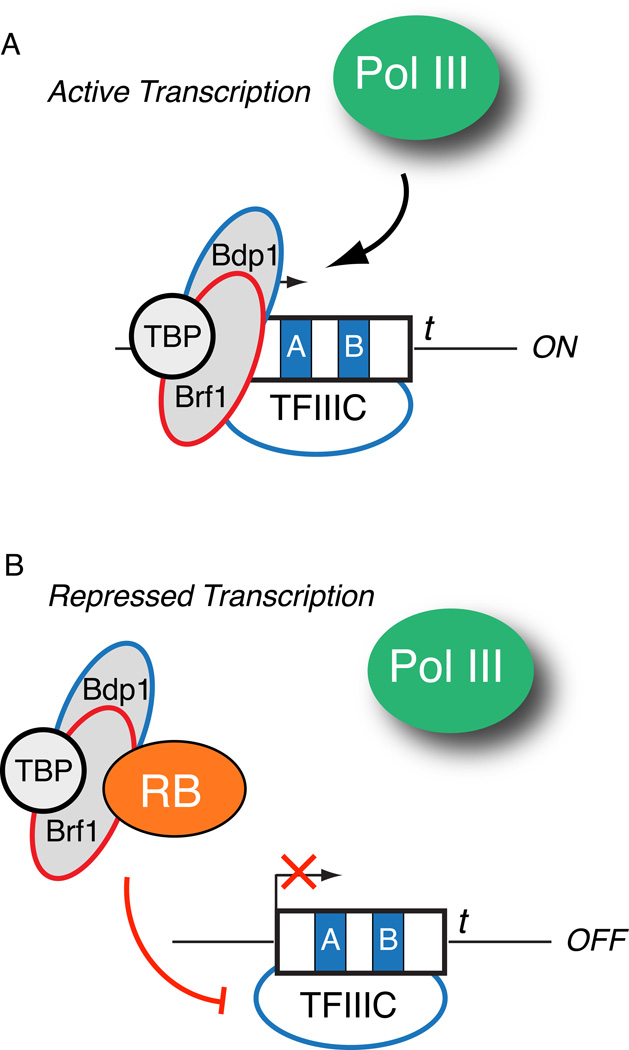

Figure 5. RB disrupts preinitiation complex assembly at type 2 genes to enact repression.

(A) Assembly of the TFIIIC/Brf1-TFIIIB preinitiation complex enables active Pol III transcription at type 2 genes. (B) RB interacts with the Brf1 component of the TFIIIB complex to prevent preinitiation complex assembly and Pol III recruitment. In vitro template commitment assays indicate that RB can also disrupt a preformed preinitiation complex in a possible hit and run mechanism.

During this initial period of RB experimentation for Pol III repression, concomitant studies of Pol II regulation had demonstrated that RB could inhibit cell cycle gene expression by stably associating with E2F at target gene promoters [98]. Some of these studies further indicated that RB directly disrupts preinitiation complex assembly involving TFIID and TFIIA on naked DNA templates [99]. An alternative mechanism involving chromatin modification was suggested from studies demonstrating that E2F/RB interacts with and recruits histone deacetylases (HDAC) [100–102] and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes [103, 104] to Pol II-transcribed target genes activated by E2F. In these studies, HDAC inactivation with trichostatin A also inhibited the RBmediated repression. RB was further demonstrated to co-purify with E2F-1, HDAC1 and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 with RB and DNMT1 cooperating to repress transcription of E2F-activated genes [105]. In this E2F model, RB repression involves chromatin regulation at both the DNA and histone levels. Interestingly, RB repression of Ad VAI gene expression by Pol III was not sensitive to HDAC inhibition with trichostatin A, suggesting that a similar chromatin-based repression mechanism might not be involved for type 2 genes. Results from template commitment assays instead suggested that recombinant RB could disrupt a pre-formed preinitiation complex and in coimmunoprecipitation studies RB impeded Brf1 association with TFIIIC and with Pol III, but not with another member of the TFIIIB complex, TBP [106]. These observations reinforced the concept that RB disrupts communication between members of the Pol III general transcription machinery to enact repression. In contrast with the prevalent RB-E2F model for repression of cell cycle genes, stable association by RB at a type 2 locus was not observed [107], suggesting that RB prevents pre-initiation complex assembly by blocking Brf1-TFIIIB loading, or in cases wherein the Brf1-TFIIIB/TFIIIC complex is formed, RB may utilize a tansient hit and run mechanism to disassemble Brf1-TFIIIB from the preinitiation complex.

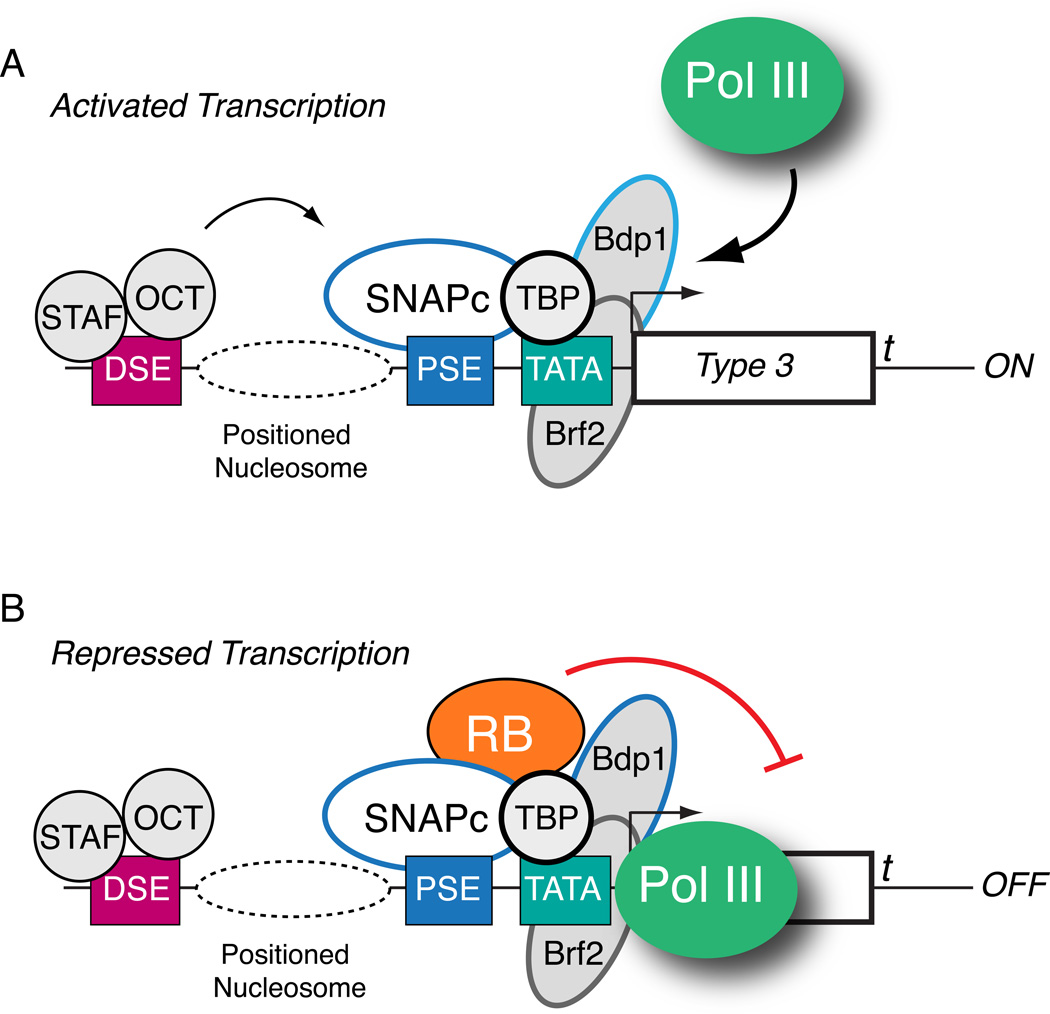

Although RB represses Pol III globally [34], distinct factors are involved in Pol III transcription of the divergent type 3 target genes, and consequently a different repression mechanism is employed to regulate expression of genes within this category [108]. Most notably, RB was observed to stably associate with the endogenous RNU6-1 locus in RB proficient cells [107]. Thus, a model involving a simple hit and run mechanism was not supported, but rather, RB repression more closely resembled some aspects of the E2F model that require substantial RB residency at target promoters. Robust protein-protein interactions between RB and two components of SNAPc, SNAP43 and SNAP50, and with TBP were observed in vitro, suggesting that promoter targeting involves multiple contacts within the preinitiation complex. Both promoter targeting and general transcription factor interactions with RB were reliant upon the AB pocket domain and C terminal region. In these studies, RB did not interact with Brf2 in vitro. Thus, RB-TFIIIB interactions may be more critical for type 1 and type 2 gene repression than for type 3 genes. Nonetheless, TBP activity was limiting during RB repression assays in vitro [108] and it remains possible that Brf2-TFIIIB plays an important role in RB repression. Interestingly, RB association with the RNU6-1 locus was detected simultaneously with components of SNAPc and Pol III [107], a phenomenon that was also observed using a U6-1 reporter gene in vitro, suggesting that RB does not necessarily disrupt preinitiation complex assembly. A model was proposed that RB inhibits Pol III promoter escape or elongation during repression of type 3 genes (Figure 6).

Figure 6. RB forms a stable association with SNAPc, TBP, and Pol III at type 3 genes during repression.

(A) Protein contacts from the Oct-1 and STAF activators stimulate preinitiation complex assembly by SNAPc and Brf2-TFIIIB during activated Pol III transcription. (B) RB can interact with multiple subunits within the preinitiation complex, including SNAP43, SNAP50, and TBP to form a stable association at the promoter along with Pol III. In this model, stable promoter binding by RB inhibits Pol III promoter escape or elongation, either directly or through effects on chromatin structure at both the histone and DNA levels.

5. Genome-wide analyses of RB and RNA polymerase III

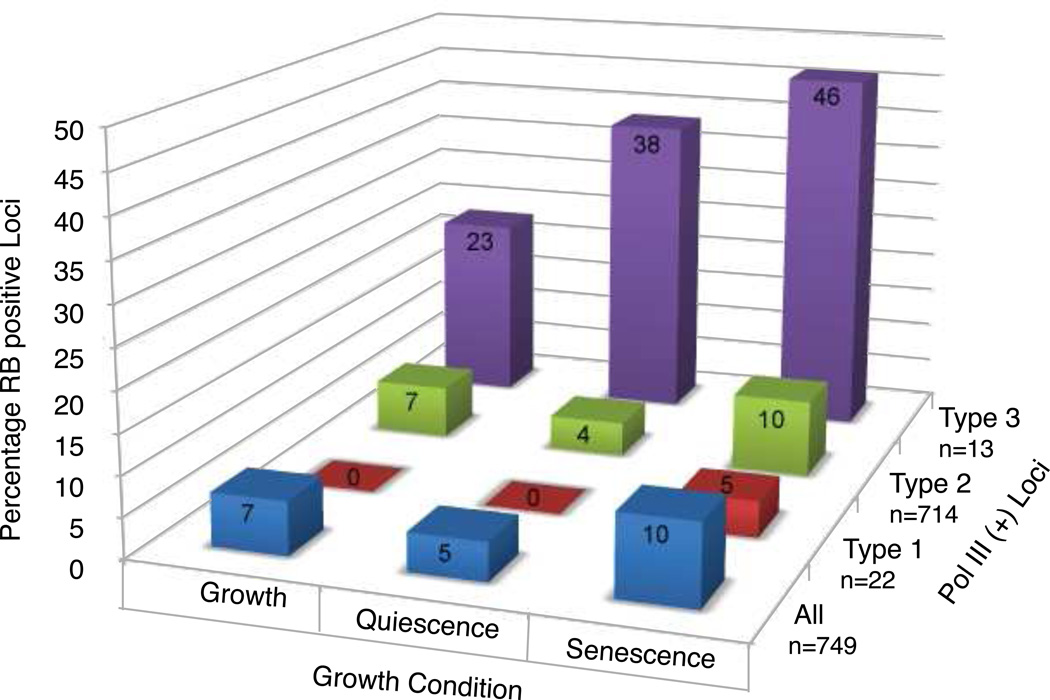

To better understand the relationship between global Pol III regulation and RB function in tumor suppression, we compared the outcomes of ChIP-Seq experiments that examined genomic association by Pol III [27] and RB during active proliferation and growth arrest in human IMR90 fibroblasts [109]. As shown in Figure 7, RB was detected at both type 2 and 3 Pol III genes in actively growing cells. RB was found to associate with more type 3 genes during arrested growth, both during quiescence induced by serum starvation and senescence induced by stable expression of a transgene expressing dominant active Ras. Interestingly, increased RB association at all three types of genes was noted during senescence. As induction of senescence represents a major mechanism for tumor suppression by RB, these observations are consistent with Pol III repression contributing to key cancer prevention networks.

Figure 7. Genome-wide analysis of RB association at Pol III transcribed genes.

Chip-Seq data describing the association by RB at genomic targets during active and arrested growth (quiescence, senescence) in human IMR90 fibroblasts [109] was compared to that observed for Pol III [27] with the percentage of RB positive genes for each gene type indicated. Type 3 genes exhibited the greatest percentage of members that were associated with RB, whereas the greatest number of RB positive loci was observed for type 2 genes. The fold enrichment observed for RB positive loci is shown in the supplemental table S2.

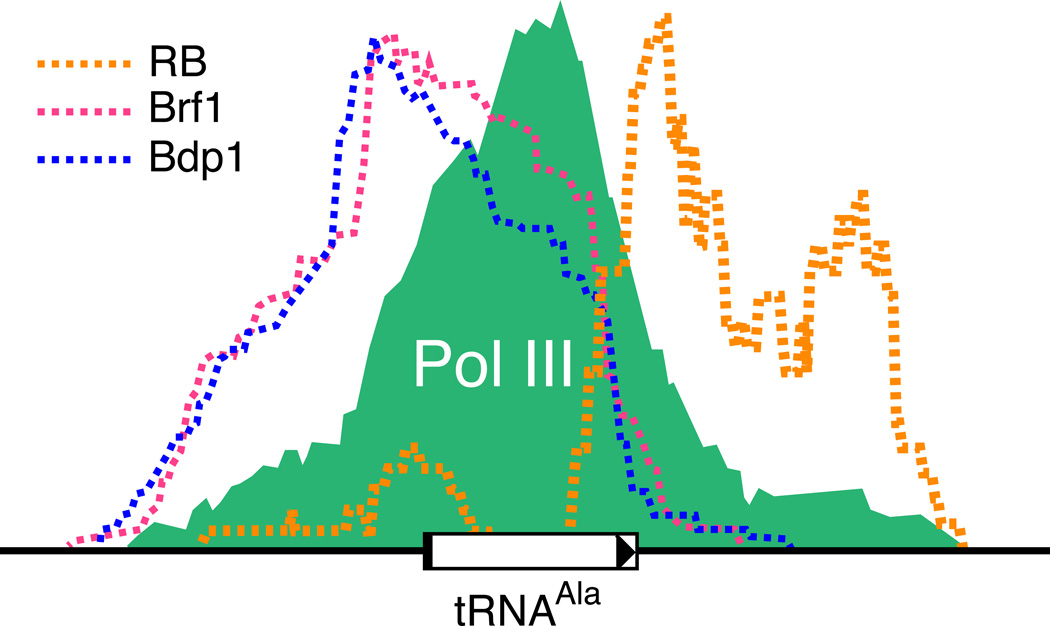

Surprisingly, the type 2 gene category contained numerically the greatest number of loci that were associated with RB, a unexpected outcome based on a repression model wherein RB primarily blocks preiniation complex assembly, as noted above. A closer examination of the relative peak positions for RB and Pol III shows that RB was bound remarkably close to the locations occupied by Pol III at some of these sites, consistent with an intimate relationship between RB and the Pol III machinery (Figure 8). In some cases, a single RB peak was observed at a locus that harbors a cluster of tRNA genes, raising the possibility that RB may extend its reach to multiple genes. It should be noted that the functional significance of RB binding at these loci has not been experimentally tested, nor has the binding of RB and Pol III at these loci been determined contemporaneously, such as through sequential ChIP assays. One likely possibility is that RB association at some type 2 genes is fortuitous, and is due to its binding at other nearby target genes, as has been observed for other Pol II factors [28, 110]. Indeed, the position of the RB peaks relative to Pol III was variable among type 2 genes with RB located upstream from the transcription start site in some examples, but downstream from the termination site in others (Supplemental Table S1). The variable positioning of these peaks indicates that an association between RB and other factors besides Brf1-TFIIIB likely underlies RB recruitment to these sites. At this time, whether the tethering of RB to neighboring Pol II-transcribed genes can influence expression of a proximally located Pol III gene is uncertain. In an alternative interpretation of this data, stable RB association at type 2 loci is direclty relevant to Pol III regulation and could be an important component of the repression mechanism. Indeed, not all tRNA genes are equivalently bound by Pol III, even within an amino acid isotype family, a property that is evolutionarily conserved [111], and thus, RB might be recruited only to tRNA genes that are poised for Pol III transcription. In this case, RB might fine tune Pol III transcript levels via regulation of only select targets within each category depending upon the growth conditions and gene utilization by the Pol III machinery.

Figure 8. RB can associate with local but variable locations at type 2 genes.

Schematic representation of the relative peak positions for Brf1 (dashed red), Bdp1 (dashed blue), Pol III (green), and RB (dashed orange). In this example of a tRNAVal gene, the RB peak was located downstream of the termination site. In other cases, the peak of RB sequence reads was located upstream and adjacently to the peak locations for Brf1 and Bdp1 (not shown). In some examples of clustered tRNA genes, RB associated with only a single member (not shown).

As noted for type 2 genes, RB also resided at some, but not all, type 3 genes in actively growing cells with RB residency observed at an increased number of loci during growth arrest. This observation is additionally consistent with a role for RB in regulation of some type 3 genes during regular cell cycle progression. Surprisingly, RB did not associate with all members within a gene family, best exemplified by the U6 gene family, which contains five actively transcribed members [112], but with only two of these exhibiting RB association. The identity of type 3 genes considered in this analysis and their RB status is shown in Table 1. Some type 3 genes did not exhibit RB association under any conditions, even though these putative RB targets harbored SNAPc and TBP (data not shown), which were previously suggested as critical for RB recruitment [107]. In vitro repression assays suggest that at least one of these candidates that lacked RB association, the Y1 gene, was sensitive to RB expression during transient transfection but repression was not as robust as other type 3 genes that were positive for RB in vivo [107]. The significance of these different binding patterns for RB repression remains to be determined, but nonetheless raises the possibility that RB may utilize different mechanisms for repression of genes within a particular family. Whether these RB negative type 3 genes are simply not targeted for repression at all or instead are repressed by a mechanism whereby RB inhibits stable PIC formation but does not reside at the loci, reminiscent of that proposed for type 1 and type 2 gene regulation, is unknown.

Table 1.

Comparison of RB and Pol III occupancy at type 3 genes.

| Type 3 Pol III+ Genes |

Condition |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | Quiescence | Senescence | ||

| 7SK | + | + | + |  |

| RNaseP | + | + | + | |

| U6ATAC | + | + | + | |

| MRP | − | + | + | |

| U6-1 | − | + | + | |

| U6-2 | − | − | + | |

| U6-7 | − | − | − |  |

| U6-8 | − | − | − | |

| U6-9 | − | − | − | |

| Y1 | − | − | − | |

| Y3 | − | − | − | |

| Y4 | − | − | − | |

| Y5 | − | − | − | |

As with the type 2 genes, the peak locations for type 3 RB positive genes and the Pol III apparatus suggest an intimate relationship between the repressor and the basal apparatus, and is consistent with previous ChIP assays that examined RB binding at the RNU6-1 locus in human RB proficient cells [107]. Nonetheless, in those studies, RB was observed to co-occupy the RNU6-1 core promoter with SNAPc and TBP, and thus it is surprising that the peak of RB binding at type 3 loci in IMR90 fibroblasts was not within the core promoter but rather was variably located within the enhancer regions (Figure 9). Thus, one question remains as to how RB can establish contacts with the preinitiation complex from this distal location. It was previously demonstrated that the U6-1 promoter harbors a nucleosome positioned between the PSE and the DSE that is important for activated Pol III transcription [113]. DNA wrapping around the nucleosome juxtaposes the activator, Oct1, and its target, the core transcription factor, SNAPc [113–115]. In this scenario, RB positioned distally to the nucleosome would similarly be brought into position to its targets within the core machinery by DNA wrapping. Consistent with the involvement of chromatinmodifying factors in RB regulation of Pol II transcription, RB expression by transient transfection facilitated DNMT1 recruitment to the RNU6-1 locus [116], suggesting that this and other chromatin modifying factors contribute to Pol III regulation during tumor suppression, a topic for future efforts. Together, these studies have uncovered an unanticipated diversity of RB tumor suppressor function in the control of Pol III.

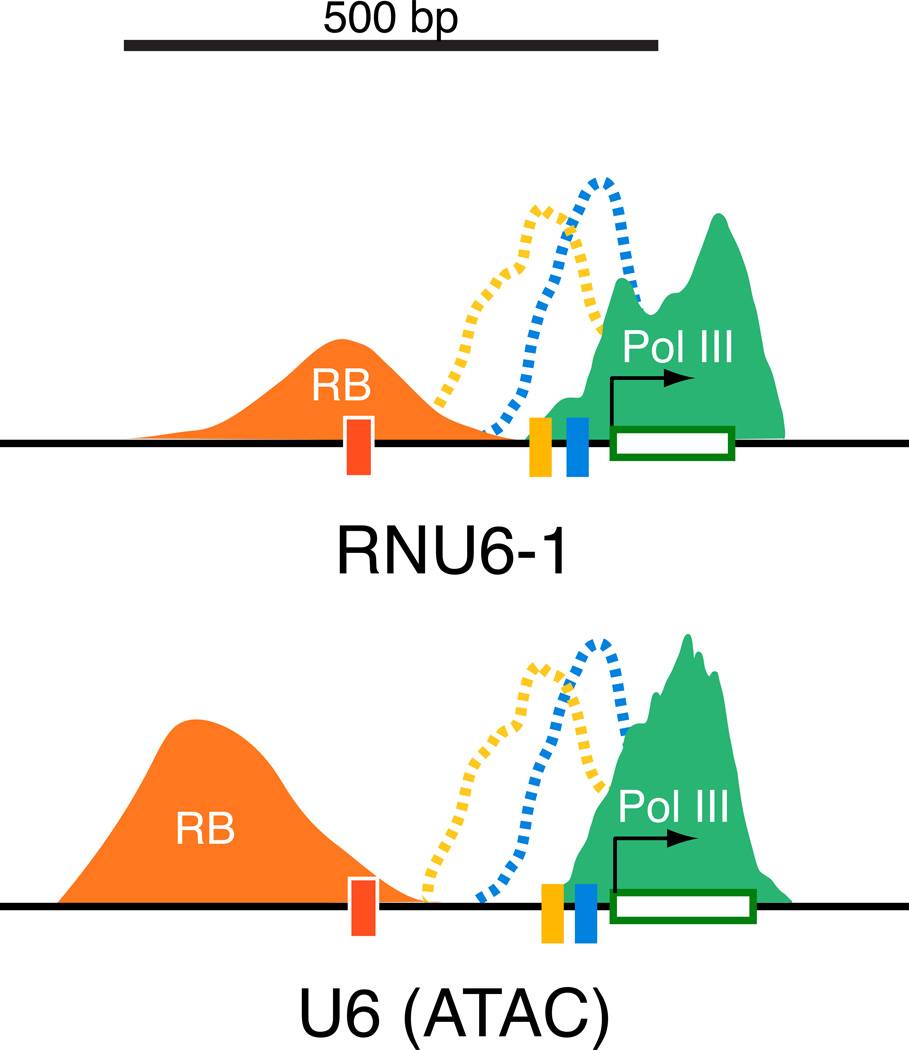

Figure 9. RB associates at variable locations within the enhancer regions of type 3 genes.

Schematic representation of relative peak positions for RB (orange) and Pol III (green) at the RNU6 (ATAC) and RNU6-1 loci. The dashed lines indicate the relative peak positions for SNAP45 (yellow) and Bdp1 (blue) that was observed at the RNU6 (ATAC) loci. In this experiment, association by SNAPc and TFIIIB at the RNU6-1 locus were not observed (106) and these peaks are included solely for reference.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table S1. Fold enrichment scores for RB positive loci.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from Michigan State University Gene Expression in Development and Disease initiative and the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM079098).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Knudson AG., Jr Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WH, Bookstein R, Hong F, Young LJ, Shew JY, Lee EY. Human retinoblastoma susceptibility gene: cloning, identification, and sequence. Science. 1987;235:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.3823889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee WH, Shew JY, Hong FD, Sery TW, Donoso LA, Young LJ, Bookstein R, Lee EY. The retinoblastoma susceptibility gene encodes a nuclear phosphoprotein associated with DNA binding activity. Nature. 1987;329:642–645. doi: 10.1038/329642a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horowitz JM, Park SH, Bogenmann E, Cheng JC, Yandell DW, Kaye FJ, Minna JD, Dryja TP, Weinberg RA. Frequent inactivation of the retinoblastoma anti-oncogene is restricted to a subset of human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2775–2779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wikenheiser-Brokamp KA. Retinoblastoma regulatory pathway in lung cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:783–793. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchkovich K, Duffy LA, Harlow E. The retinoblastoma protein is phosphorylated during specific phases of the cell cycle. Cell. 1989;58:1097–1105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen PL, Scully P, Shew JY, Wang JY, Lee WH. Phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma gene product is modulated during the cell cycle and cellular differentiation. Cell. 1989;58:1193–1198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90517-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeCaprio JA, Ludlow JW, Lynch D, Furukawa Y, Griffin J, Piwnica-Worms H, Huang CM, Livingston DM. The product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene has properties of a cell cycle regulatory element. Cell. 1989;58:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mihara K, Cao XR, Yen A, Chandler S, Driscoll B, Murphree AL, T'Ang A, Fung YK. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of phosphorylation of the human retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1989;246:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.2588006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludlow JW, Shon J, Pipas JM, Livingston DM, DeCaprio JA. The retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product undergoes cell cycle-dependent dephosphorylation and binding to and release from SV40 large T. Cell. 1990;60:387–396. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90590-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodrich DW, Wang NP, Qian YW, Lee EY, Lee WH. The retinoblastoma gene product regulates progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Cell. 1991;67:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90181-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ewen ME, Sluss HK, Sherr CJ, Matsushime H, Kato J, Livingston DM. Functional interactions of the retinoblastoma protein with mammalian D- type cyclins. Cell. 1993;73:487–497. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90136-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert SW, Ewen ME, Sherr CJ. Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes Dev. 1993;7:331–342. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dynlacht BD, Flores O, Lees JA, Harlow E. Differential regulation of E2F transactivation by cyclin/cdk2 complexes. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1772–1786. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagchi S, Weinmann R, Raychaudhuri P. The retinoblastoma protein copurifies with E2F-I, an E1A-regulated inhibitor of the transcription factor E2F. Cell. 1991;65:1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90558-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao L, Faha B, Dembski M, Tsai LH, Harlow E, Dyson N. Independent binding of the retinoblastoma protein and p107 to the transcription factor E2F. Nature. 1992;355:176–179. doi: 10.1038/355176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chellappan SP, Hiebert S, Mudryj M, Horowitz JM, Nevins JR. The E2F transcription factor is a cellular target for the RB protein. Cell. 1991;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90557-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiebert SW, Chellappan SP, Horowitz JM, Nevins JR. The interaction of RB with E2F coincides with an inhibition of the transcriptional activity of E2F. Genes Dev. 1992;6:177–185. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zacksenhaus E, Jiang Z, Chung D, Marth JD, Phillips RA, Gallie BL. pRb controls proliferation, differentiation, and death of skeletal muscle cells and other lineages during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3051–3064. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Guo K, Wills KN, Walsh K. Rb functions to inhibit apoptosis during myocyte differentiation. Cancer Res. 1997;57:351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh JK, Chan FS, O'Connor DJ, Mittnacht S, Zhong S, Lu X. RB regulates the stability and the apoptotic function of p53 via MDM2. Mol Cell. 1999;3:181–193. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jawdekar GW, Henry RW. Transcriptional regulation of human small nuclear RNA genes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dumay-Odelot H, Durrieu-Gaillard S, Da Silva D, Roeder RG, Teichmann M. Cell growth- and differentiation-dependent regulation of RNA polymerase III transcription. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3687–3699. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.18.13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schramm L, Hernandez N. Recruitment of RNA polymerase III to its target promoters. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2593–2620. doi: 10.1101/gad.1018902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canella D, Praz V, Reina JH, Cousin P, Hernandez N. Defining the RNA polymerase III transcriptome: Genome-wide localization of the RNA polymerase III transcription machinery in human cells. Genome Res. 2010;20:710–721. doi: 10.1101/gr.101337.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moqtaderi Z, Wang J, Raha D, White RJ, Snyder M, Weng Z, Struhl K. Genomic binding profiles of functionally distinct RNA polymerase III transcription complexes in human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:635–640. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canella D, Bernasconi D, Gilardi F, LeMartelot G, Migliavacca E, Praz V, Cousin P, Delorenzi M, Hernandez N. A multiplicity of factors contributes to selective RNA polymerase III occupancy of a subset of RNA polymerase III genes in mouse liver. Genome Res. 2012;22:666–680. doi: 10.1101/gr.130286.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh K, Carey M, Saragosti S, Botchan M. Expression of enhanced levels of small RNA polymerase III transcripts encoded by the B2 repeats in simian virus 40-transformed mouse cells. Nature. 1985;314:553–556. doi: 10.1038/314553a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carey MF, Singh K, Botchan M, Cozzarelli NR. Induction of specific transcription by RNA polymerase III in transformed cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3068–3076. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.9.3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White RJ, Stott D, Rigby PW. Regulation of RNA polymerase III transcription in response to Simian virus 40 transformation. Embo J. 1990;9:3713–3721. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White RJ. RNA polymerase III transcription and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:3208–3216. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White RJ, Trouche D, Martin K, Jackson SP, Kouzarides T. Repression of RNA polymerase III transcription by the retinoblastoma protein. Nature. 1996;382:88–90. doi: 10.1038/382088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nasmyth K. Retinoblastoma protein. Another role rolls in. Nature. 1996;382:28–29. doi: 10.1038/382028a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson SA, Dubeau L, Johnson DL. Enhanced RNA polymerase IIIdependent transcription is required for oncogenic transformation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19184–19191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802872200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah AA, Rosen A, Hummers L, Wigley F, Casciola-Rosen L. Close temporal relationship between onset of cancer and scleroderma in patients with RNA polymerase I/III antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2787–2795. doi: 10.1002/art.27549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Politz JC, Pederson T, Huang S. RNA polymerase III transcripts and the PTB protein are essential for the integrity of the perinucleolar compartment. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2425–2435. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kamath RV, Thor AD, Wang C, Edgerton SM, Slusarczyk A, Leary DJ, Wang J, Wiley EL, Jovanovic B, Wu Q, Nayar R, Kovarik P, Shi F, Huang S. Perinucleolar compartment prevalence has an independent prognostic value for breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:246–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kopp K, Huang S. Perinucleolar compartment and transformation. J Cell Biochem. 2005;95:217–225. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slusarczyk A, Kamath R, Wang C, Anchel D, Pollock C, Lewandowska MA, Fitzpatrick T, Bazett-Jones DP, Huang S. Structure and function of the perinucleolar compartment in cancer cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2010;75:599–605. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norton JT, Pollock CB, Wang C, Schink JC, Kim JJ, Huang S. Perinucleolar compartment prevalence is a phenotypic pancancer marker of malignancy. Cancer. 2008;113:861–869. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norton JT, Wang C, Gjidoda A, Henry RW, Huang S. The perinucleolar compartment is directly associated with DNA. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4090–4101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807255200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson LF, Abelson HT, Green H, Penman S. Changes in RNA in relation to growth of the fibroblast. I. Amounts of mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA in resting and growing cells. Cell. 1974;1:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mauck JC, Green H. Regulation of pre-transfer RNA synthesis during transition from resting to growing state. Cell. 1974;3:171–177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gottesfeld JM, Wolf VJ, Dang T, Forbes DJ, Hartl P. Mitotic repression of RNA polymerase III transcription in vitro mediated by phosphorylation of a TFIIIB component. Science. 1994;263:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.8272869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White RJ, Gottlieb TM, Downes CS, Jackson SP. Cell cycle regulation of RNA polymerase III transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6653–6662. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu P, Samudre K, Wu S, Sun Y, Hernandez N. CK2 phosphorylation of Bdp1 executes cell cycle-specific RNA polymerase III transcription repression. Mol Cell. 2004;16:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simmen KA, Bernues J, Lewis JD, Mattaj IW. Cofractionation of the TATA-binding protein with the RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIB. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5889–5898. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.22.5889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kassavetis GA, Joazeiro CA, Pisano M, Geiduschek EP, Colbert T, Hahn S, Blanco JA. The role of the TATA-binding protein in the assembly and function of the multisubunit yeast RNA polymerase III transcription factor, TFIIIB. Cell. 1992;71:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90399-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lobo SM, Tanaka M, Sullivan ML, Hernandez N. A TBP complex essential for transcription from TATA-less but not TATA- containing RNA polymerase III promoters is part of the TFIIIB fraction. Cell. 1992;71:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90397-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taggart AK, Fisher TS, Pugh BF. The TATA-binding protein and associated factors are components of pol III transcription factor TFIIIB. Cell. 1992;71:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90396-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buratowski S, Zhou H. A suppressor of TBP mutations encodes an RNA polymerase III transcription factor with homology to TFIIB. Cell. 1992;71:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90351-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colbert T, Hahn S. A yeast TFIIB-related factor involved in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1940–1949. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopez-De-Leon A, Librizzi M, Puglia K, Willis IM. PCF4 encodes an RNA polymerase III transcription factor with homology to TFIIB. Cell. 1992;71:211–220. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90350-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schramm L, Pendergrast PS, Sun Y, Hernandez N. Different human TFIIIB activities direct RNA polymerase III transcription from TATA-containing and TATA-less promoters. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2650–2663. doi: 10.1101/gad.836400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teichmann M, Wang Z, Roeder RG. A stable complex of a novel transcription factor IIB- related factor, human TFIIIB50, and associated proteins mediate selective transcription by RNA polymerase III of genes with upstream promoter elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14200–14205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kassavetis GA, Nguyen ST, Kobayashi R, Kumar A, Geiduschek EP, Pisano M. Cloning, expression, and function of TFC5, the gene encoding the B" component of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9786–9790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roberts S, Miller SJ, Lane WS, Lee S, Hahn S. Cloning and functional characterization of the gene encoding the TFIIIB90 subunit of RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14903–14909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruth J, Conesa C, Dieci G, Lefebvre O, Dusterhoft A, Ottonello S, Sentenac A. A suppressor of mutations in the class III transcription system encodes a component of yeast TFIIIB. Embo J. 1996;15:1941–1949. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sadowski CL, Henry RW, Lobo SM, Hernandez N. Targeting TBP to a non-TATA box cis-regulatory element: a TBP-containing complex activates transcription from snRNA promoters through the PSE. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1535–1548. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henry RW, Sadowski CL, Kobayashi R, Hernandez N. A TBP-TAF complex required for transcription of human snRNA genes by RNA polymerase II and III. Nature. 1995;374:653–656. doi: 10.1038/374653a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sadowski CL, Henry RW, Kobayashi R, Hernandez N. The SNAP45 subunit of the small nuclear RNA (snRNA) activating protein complex is required for RNA polymerase II and III snRNA gene transcription and interacts with the TATA box binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4289–4293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Henry RW, Ma B, Sadowski CL, Kobayashi R, Hernandez N. Cloning and characterization of SNAP50, a subunit of the snRNA- activating protein complex SNAPc. Embo J. 1996;15:7129–7136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Henry RW, Mittal V, Ma B, Kobayashi R, Hernandez N. SNAP19 mediates the assembly of a functional core promoter complex (SNAPc) shared by RNA polymerases II and III. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2664–2672. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wong MW, Henry RW, Ma B, Kobayashi R, Klages N, Matthias P, Strubin M, Hernandez N. The large subunit of basal transcription factor SNAPc is a Myb domain protein that interacts with Oct-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:368–377. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy S, Yoon JB, Gerster T, Roeder RG. Oct-1 and Oct-2 potentiate functional interactions of a transcription factor with the proximal sequence element of small nuclear RNA genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3247–3261. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoon JB, Murphy S, Bai L, Wang Z, Roeder RG. Proximal sequence element-binding transcription factor (PTF) is a multisubunit complex required for transcription of both RNA polymerase II- and RNA polymerase III-dependent small nuclear RNA genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2019–2027. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoon JB, Roeder RG. Cloning of two proximal sequence element-binding transcription factor subunits (gamma and delta) that are required for transcription of small nuclear RNA genes by RNA polymerases II and III and interact with the TATA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bai L, Wang Z, Yoon JB, Roeder RG. Cloning and characterization of the beta subunit of human proximal sequence element-binding transcription factor and its involvement in transcription of small nuclear RNA genes by RNA polymerases II and III. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5419–5426. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mital R, Kobayashi R, Hernandez N. RNA polymerase III transcription from the human U6 and adenovirus type 2 VAI promoters has different requirements for human BRF, a subunit of human TFIIIB. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7031–7042. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCulloch V, Hardin P, Peng W, Ruppert JM, Lobo-Ruppert SM. Alternatively spliced hBRF variants function at different RNA polymerase III promoters. Embo J. 2000;19:4134–4143. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kassavetis GA, Braun BR, Nguyen LH, Geiduschek EP, cerevisiae S. TFIIIB is the transcription initiation factor proper of RNA polymerase III, while TFIIIA and TFIIIC are assembly factors. Cell. 1990;60:235–245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Werner M, Chaussivert N, Willis IM, Sentenac A. Interaction between a complex of RNA polymerase III subunits and the 70- kDa component of transcription factor IIIB. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20721–20724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kenneth NS, Marshall L, White RJ. Recruitment of RNA polymerase III in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3757–3764. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghavidel A, Schultz MC. Casein kinase II regulation of yeast TFIIIB is mediated by the TATA- binding protein. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2780–2789. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghavidel A, Schultz MC. TATA binding protein-associated CK2 transduces DNA damage signals to the RNA polymerase III transcriptional machinery. Cell. 2001;106:575–584. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hu P, Wu S, Hernandez N. A minimal RNA polymerase III transcription system from human cells reveals positive and negative regulatory roles for CK2. Mol Cell. 2003;12:699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fairley JA, Mitchell LE, Berg T, Kenneth NS, von Schubert C, Sillje HH, Medema RH, Nigg EA, White RJ. Direct regulation of tRNA and 5S rRNA gene transcription by Polo-like kinase 1. Mol Cell. 2012;45:541–552. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leresche A, Wolf VJ, Gottesfeld JM. Repression of RNA polymerase II and III transcription during M phase of the cell cycle. Exp Cell Res. 1996;229:282–288. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fairley JA, Scott PH, White RJ. TFIIIB is phosphorylated, disrupted and selectively released from tRNA promoters during mitosis in vivo. Embo J. 2003;22:5841–5850. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gu L, Husain-Ponnampalam R, Hoffmann-Benning S, Henry RW. The protein kinase CK2 phosphorylates SNAP190 to negatively regulate SNAPC DNA binding and human U6 transcription by RNA polymerase III. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27887–27896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hinkley CS, Hirsch HA, Gu L, LaMere B, Henry RW. The small nuclear RNA-activating protein 190 Myb DNA binding domain stimulates TATA box-binding protein-TATA box recognition. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18649–18657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gu L, Esselman WJ, Henry RW. Cooperation between small nuclear RNA-activating protein complex (SNAPC) and TATA-box-binding protein antagonizes protein kinase CK2 inhibition of DNA binding by SNAPC. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27697–27704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Felton-Edkins ZA, Fairley JA, Graham EL, Johnston IM, White RJ, Scott PH. The mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase ERK induces tRNA synthesis by phosphorylating TFIIIB. Embo J. 2003;22:2422–2432. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.White RJ, Gottlieb TM, Downes CS, Jackson SP. Mitotic regulation of a TATA-binding-protein-containing complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1983–1992. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sutcliffe JE, Cairns CA, McLees A, Allison SJ, Tosh K, White RJ. RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB is a target for repression by pocket proteins p107 and p130. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4255–4261. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaelin WG, Jr, Ewen ME, Livingston DM. Definition of the minimal simian virus 40 large T antigen- and adenovirus E1A-binding domain in the retinoblastoma gene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3761–3769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang NP, Chen PL, Huang S, Donoso LA, Lee WH, Lee EY. DNA-binding activity of retinoblastoma protein is intrinsic to its carboxyl-terminal region. Cell Growth Differ. 1990;1:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Qin XQ, Chittenden T, Livingston DM, Kaelin WG., Jr Identification of a growth suppression domain within the retinoblastoma gene product. Genes Dev. 1992;6:953–964. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang H, Williams BO, Hinds PW, Shih TS, Jacks T, Bronson RT, Livingston DM. Tumor suppression by a severely truncated species of retinoblastoma protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3103–3110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.3103-3110.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Classon M, Salama S, Gorka C, Mulloy R, Braun P, Harlow E. Combinatorial roles for pRB, p107, and p130 in E2F-mediated cell cycle control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10820–10825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190343497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Black EP, Huang E, Dressman H, Rempel R, Laakso N, Asa SL, Ishida S, West M, Nevins JR. Distinct gene expression phenotypes of cells lacking Rb and Rb family members. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3716–3723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stengel KR, Thangavel C, Solomon DA, Angus SP, Zheng Y, Knudsen ES. Retinoblastoma/p107/p130 pocket proteins: protein dynamics and interactions with target gene promoters. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19265–19271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808740200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Scott PH, Cairns CA, Sutcliffe JE, Alzuherri HM, McLees A, Winter AG, White RJ. Regulation of RNA polymerase III transcription during cell cycle entry. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1005–1014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Larminie CG, Cairns CA, Mital R, Martin K, Kouzarides T, Jackson SP, White RJ. Mechanistic analysis of RNA polymerase III regulation by the retinoblastoma protein. Embo J. 1997;16:2061–2071. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chu WM, Wang Z, Roeder RG, Schmid CW. RNA polymerase III transcription repressed by Rb through its interactions with TFIIIB and TFIIIC2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14755–14761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weintraub SJ, Chow KN, Luo RX, Zhang SH, He S, Dean DC. Mechanism of active transcriptional repression by the retinoblastoma protein. Nature. 1995;375:812–815. doi: 10.1038/375812a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ross JF, Liu X, Dynlacht BD. Mechanism of transcriptional repression of E2F by the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell. 1999;3:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brehm A, Miska EA, McCance DJ, Reid JL, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature. 1998;391:597–601. doi: 10.1038/35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luo RX, Postigo AA, Dean DC. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell. 1998;92:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Groisman R, Naguibneva I, Robin P, Lorain S, Le Villain JP, Troalen F, Trouche D, Harel-Bellan A. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature. 1998;391:601–605. doi: 10.1038/35410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Trouche D, Le Chalony C, Muchardt C, Yaniv M, Kouzarides T. RB and hbrm cooperate to repress the activation functions of E2F1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11268–11273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Strobeck MW, Knudsen KE, Fribourg AF, DeCristofaro MF, Weissman BE, Imbalzano AN, Knudsen ES. BRG-1 is required for RB-mediated cell cycle arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7748–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.7748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Robertson KD, Ait-Si-Ali S, Yokochi T, Wade PA, Jones PL, Wolffe AP. DNMT1 forms a complex with Rb, E2F1 and HDAC1 and represses transcription from E2F-responsive promoters. Nat Genet. 2000;25:338–342. doi: 10.1038/77124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sutcliffe JE, Brown TR, Allison SJ, Scott PH, White RJ. Retinoblastoma protein disrupts interactions required for RNA polymerase III transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9192–9202. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9192-9202.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hirsch HA, Jawdekar GW, Lee KA, Gu L, Henry RW. Distinct mechanisms for repression of RNA polymerase III transcription by the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5989–5999. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5989-5999.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hirsch HA, Gu L, Henry RW. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein targets distinct general transcription factors to regulate RNA polymerase III gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9182–9191. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9182-9191.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chicas A, Wang X, Zhang C, McCurrach M, Zhao Z, Mert O, Dickins RA, Narita M, Zhang M, Lowe SW. Dissecting the unique role of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor during cellular senescence. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Raha D, Wang Z, Moqtaderi Z, Wu L, Zhong G, Gerstein M, Struhl K, Snyder M. Close association of RNA polymerase II and many transcription factors with Pol III genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3639–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911315106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kutter C, Brown GD, Goncalves A, Wilson MD, Watt S, Brazma A, White RJ, Odom DT. Pol III binding in six mammals shows conservation among amino acid isotypes despite divergence among tRNA genes. Nat Genet. 2011;43:948–955. doi: 10.1038/ng.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Domitrovich AM, Kunkel GR. Multiple, dispersed human U6 small nuclear RNA genes with varied transcriptional efficiencies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2344–2352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhao X, Pendergrast PS, Hernandez N. A positioned nucleosome on the human U6 promoter allows recruitment of SNAPc by the Oct-1 POU domain. Mol Cell. 2001;7:539–549. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ford E, Strubin M, Hernandez N. The Oct-1 POU domain activates snRNA gene transcription by contacting a region in the SNAPc largest subunit that bears sequence similarities to the Oct-1 coactivator OBF-1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3528–3540. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hovde S, Hinkley CS, Strong K, Brooks A, Gu L, Henry RW, Geiger J. Activator recruitment by the general transcription machinery: X-ray structural analysis of the Oct-1 POU domain/human U1 octamer/SNAP190 peptide ternary complex. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2772–2777. doi: 10.1101/gad.1021002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Selvakumar T, Gjidoda A, Hovde SL, Henry RW. Regulation of human RNA polymerase III transcription by DNMT1 and DNMT3a DNA methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7039–7050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.285601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1. Fold enrichment scores for RB positive loci.