Abstract

Objectives

The primary objective of this multicenter registry was to study the prognostic value of PET MPI and the improved classification of risk in a large cohort of patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease (CAD).

Background

Limited prognostic data are available for myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) with positron emission tomography (PET).

Methods

7,061 patients from 4 centers underwent a clinically indicated rest/stress rubidium-82 PET MPI with a median follow-up of 2.2 years. The primary outcome of this study was cardiac-death (169 patients) and the secondary outcome was all-cause death (570 patients). Net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination (IDI) analyses were performed.

Results

Risk-adjusted hazard of cardiac-death increased with each 10% abnormal myocardium with mildly, moderately or severely abnormal stress PET [hazard ratio 2.3 (95% CI 1.4–3.8, P=0.001), 4.2 (95% CI 2.3–7.5, P<0.001), and 4.9 (95% CI 2.5–9.6, P <0.0001), respectively, normal MPI: referent]. Addition of %myocardium ischemic and scarred to clinical information (age, female sex, body mass index, history of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, angina, betablocker use, prior revascularization and rest heart rate) improved the model performance [C-statistic 0.805 (95% CI, 0.772–0.838) to 0.839 (95% CI, 0.809–0.869)] and risk reclassification for cardiac-death [NRI 0.116 (95% CI 0.021–0.210)] with smaller improvements in risk assessment for all-cause death.

Conclusions

In patients with known or suspected CAD, the extent and severity of ischemia and scar on PET MPI provide powerful and incremental risk estimates of cardiac-death and all-cause death compared to traditional coronary risk factors.

Keywords: positron emission tomography, registry, prognosis, myocardial perfusion imaging, risk reclassification

INTRODUCTION

Several studies have demonstrated the prognostic value of positron emission tomography (PET) myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI)(1–7) using conventional metrics (significant hazard ratio in multivariable risk adjusted models, increment in model Chi square value, improved model fit by a lower Akaike information criterion (AIC), and an increase in the area under the receiver operator characteristic curve). While these conventional metrics have demonstrated a strong and independent association between abnormal MPI and adverse clinical outcomes, these were relatively small and single-center studies and were limited in determining the clinical utility of the PET MPI. The clinical utility of a risk marker is its ability to reclassify risk when added to the traditional risk model. Improved risk reclassification will allow us to make clinical decisions that may lead to changes in management and clinical outcomes. Therefore, the aim of our study was to determine the incremental prognostic value and the clinical utility of rest and stress perfusion defects on PET MPI over clinical risk factors using the traditional and novel metrics of risk reclassification in a large number of patients with known or suspected CAD using a large multi-center PET registry.

METHODS

Registry methods

Four centers participated in this multi-center PET registry and enrolled 7,061 patients. Each center enrolled a patients clinically referred for a pharmacological stress Rubidium-82 (Rb-82) MPI. Data from some of the patients (n=3,884) were included in prior publications.(2,4,6,8,9) Each center had institutional review board approval for the study. Study methods are shown in much greater detail in the Appendix section.

Myocardial perfusion imaging methods

Patients were instructed to refrain from caffeine intake for at least 12 hours prior to the vasodilator study. Each patient underwent Rb-82 MPI using a dedicated or a hybrid PET/CT scanner using site specific protocols.

Follow-up methods

Cardiac-death was the primary end-point and all-cause death the secondary endpoint of this study. During follow-up, 3 of the 4 centers ascertained the cause of death and identified 169 cardiac-deaths in 6, 037 patients (2.9%, 2.9% and 2.2%, at each site). This cohort was used for the analyses of the primary end-point, cardiac-death. All-cause death (N=570) was studied in 7, 061 patients from 4 sites (9.8%, 8.2%, 9.2% and 3.9%, at each site). The median duration of follow-up for the entire cohort was 2.2 years (interquartile range, 1.3–3.3 years).

Statistical Analysis

We employed standardized approaches to data analysis including comparisons of categorical variables with χ2 statistics and t-tests for continuous measures.

Survival Analyses and Prognostic Value

Univariable associations of clinical and PET variables with death outcomes were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards models. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted.

In our multivariable Cox model, we examined the unique increase in the relative hazard for cardiac-death and all-cause death by % scarred and % ischemic perfusion abnormalities on MPI. All variables for the Cox models were chosen a priori and included age, coronary risk factors, medication use and symptoms on presentation along with the PET data.

Analyses for incremental prognostic value and risk reclassification

Predicted cardiac-death from each Cox model was subset into 3 categories using the previously established risk thresholds of < 1%, 1–2.9% and > 3%/year (events rates at 2 years of follow-up are shown in the results).(10) Predicted all-cause death was subset into 3 categories including < 2.5%, 2.5–7.4%, and ≥ 7.5% /year (events rates at 2 years of follow-up are shown in the results). Higher risk thresholds were used for all-cause death based on the distribution of cardiac-deaths and all-cause deaths in the 6, 037 patients with both events recorded. The NRI methodologies of Pencina were applied including both categorical and continuous estimates,(11) using SAS methods for calculating the NRI for survival data. (11,12) In 2,102 patients with rest left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) data, we explored the incremental prognostic value of PET MPI to a clinical model incorporating rest LVEF.

RESULTS

The baseline demographics and risk factors stratified by categories of % myocardium abnormal at stress are listed in Table 1. The percent of normal scans in this registry was 44% (47%, 40%, 57%, and 41%, respectively for each of the sites in this registry).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics from Multicenter PET Prognosis Registry in 7,061 Patients

| % Abnormal Myocardium on Stress MPI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| 0% (n=3109) | 0.1–9.9% (n=2604) | 10–19.9% (n=688) | ≥20% (n=660) | P-value | |

|

| |||||

| Age (Years) | 62±13 | 63±13 | 67±12 | 67±12 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Female sex | 58.4% | 44.0% | 30.7% | 26.4% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Body mass index (BMI, Kg/m2) | 29.5±7 | 31±7 | 30±7 | 29±6 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension | 65.0% | 67.9% | 76.5% | 72.1% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Diabetes | 22.6% | 27.0% | 37.8% | 39.1% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Dyslipidemia | 59.8% | 63.7% | 73.1% | 74.2% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Smoking | 18.7% | 22.9% | 27.3% | 24.1% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Obesity | 38.3% | 48.8% | 42.9% | 37.1% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Reason for test: Angina (Chest pain or Dyspnea) | 66.4% | 63.4% | 62.1% | 62.0% | 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| Reasons for test: other | 33.6% | 36.6% | 37.9% | 38.0% | 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| Aspirin | 45.7% | 50.4% | 63.5% | 66.4% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Beta-blocker | 39.9% | 47.4% | 67.0% | 67.7% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| History of MI | 9% | 19.3% | 46.4% | 57.7% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| History of PCI | 10.7% | 17.8% | 31.5% | 32.4% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| History of CABG | 5% | 13.9% | 28.8% | 36.1% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| History of CABG or PCI | 14.2% | 28.0% | 50.7% | 57.0% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Rest Heart Rate (bpm) | 69±12 | 67±12 | 67±13 | 69±12 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Peak Heart Rate (bpm) | 89±15 | 86±16 | 81±16 | 82±16 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Rest Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 135±24 | 135±24 | 136±24 | 131±24 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Peak Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 127±23 | 129±22 | 127±27 | 120±23 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| % Abnormal Myocardium at Rest | |||||

|

| |||||

| 0% | 100% | 27.8% | 21.4% | 9.5% | <0.0001 |

| 0.1–9.9% | 0% | 72.2% | 53.9% | 23.9% | |

| 10–19.9% | 0% | 0% | 24.7% | 24.5% | |

| ≥20% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 42.0% | |

|

| |||||

| Cardiac-death | 0.8% | 2.5% | 6.1% | 9.7% | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| All-cause death | 5.1% | 7.8% | 12.8% | 18.0% | <0.0001 |

Categorical variables were compared using a χ2 likelihood ratio or linear-by-linear χ2 association statistic. Continuous variables were compared using an ANOVA test. Smoking (current). Other reasons for the PET study included evaluation for heart failure, preoperative testing, troponin elevation, syncope, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias.

Univariable associations between cardiovascular risk factors, Rb-82 PET MPI and outcomes

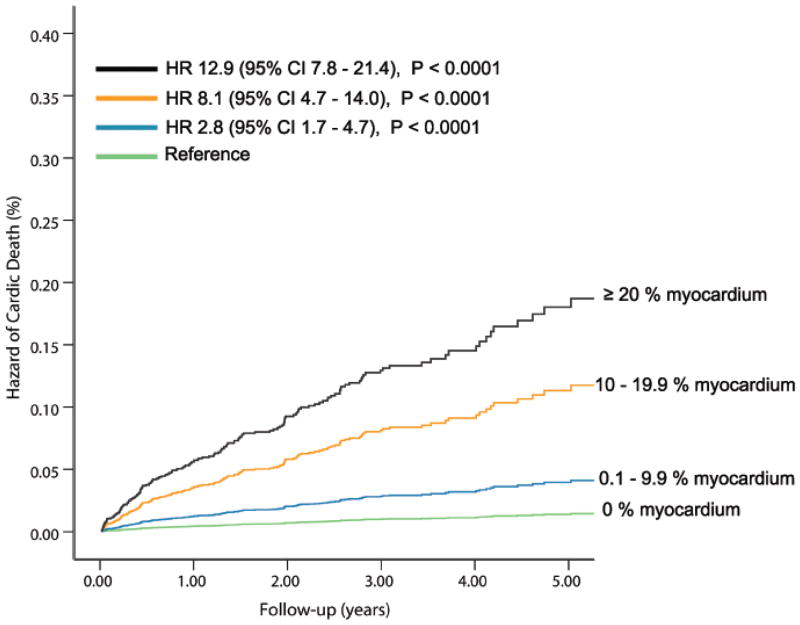

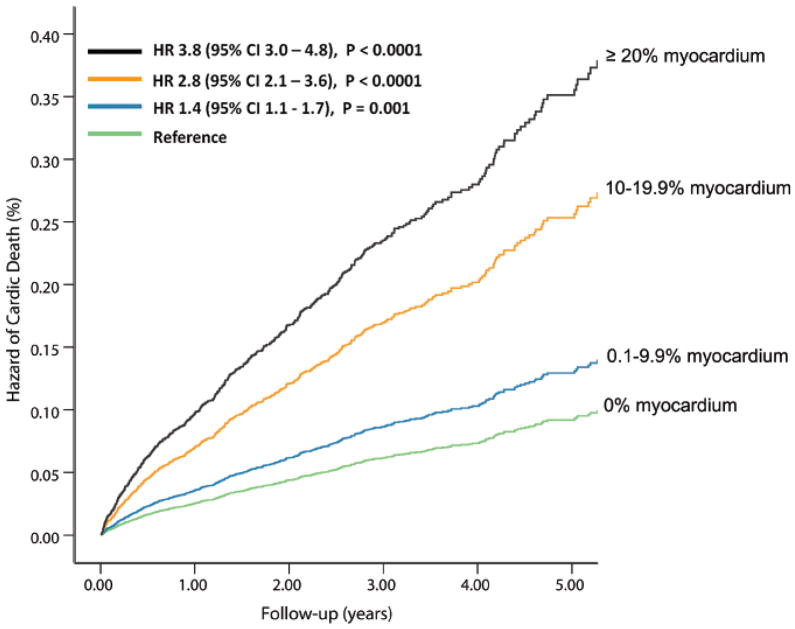

The univariable clinical and PET predictors of cardiac-death and all-cause death are listed in Table 2 and online Table 1. The % myocardium abnormal, % myocardium ischemic, and % myocardium scarred were significant univariable predictors of cardiac-death and all-cause death (Figures 1A and 1B).

Table 2.

Univariable Hazard Ratios for Cardiac-death (N=6, 037)

| Variables | HR | 95.0% CI for HR | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 1.80 | 1.70–1.90 | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 0.50 | 0.92–1.80 | <0.0001 |

| Hx Hypertension | 1.29 | 1.19–1.50 | <0.0001 |

| Hx Diabetes | 2.41 | 1.77–3.28 | <0.0001 |

| Hx Dyslipidemia | 0.81 | 0.59–1.10 | <0.0001 |

| Hx Smoking | 1.24 | 0.88–1.75 | 0.2 |

| Hx Angina | 0.66 | 0.48–0.89 | 0.007 |

| Body mass index | 0.97 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.006 |

| Hx PCI | 1.57 | 1.10–2.30 | 0.02 |

| Hx CABG | 2.36 | 1.66–3.36 | <0.0001 |

| Aspirin | 1.20 | 0.86–1.70 | 0.3 |

| Beta-blockers | 1.45 | 1.06–1.97 | <0.0001 |

| Rest heart rate* | 1.30 | 1.30–1.40 | <0.0001 |

| % Myo abnormal* | 1.60 | 1.60–180 | <0.0001 |

| % Myo scarred* | 1.90 | 1.70–2.10 | <0.0001 |

| % Myo ischemic* | 1.70 | 1.50–1.90 | <0.0001 |

HR = hazard ratio ; CI = confidence interval; Hx = history of; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG = coronary artery bypass surgery; myo = myocardium;

per 10 unit change.

Figure 1. Unadjusted Hazard of Events by % Abnormal Myocardium on Vasodilator Stress Rb-82 PET.

Hazard of cardiac-death (A, 6, 037 patients, N= 169 cardiac-deaths) and all-cause death (B, 7,061 patients, N=570 all-cause deaths) was lowest in patients with normal PET MPI and increased gradually in patients with minimal, mild, moderate or severe degrees of scan abnormality.

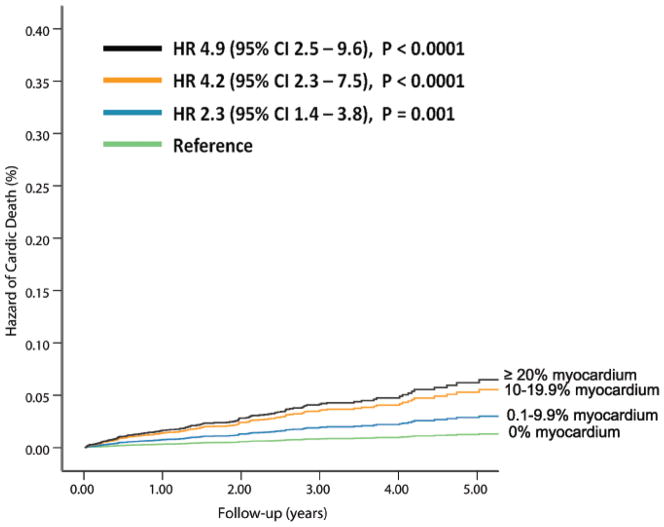

Multivariable Cox Models for the estimation of cardiac-death

The independent predictors of cardiac-death (N=6, 037, Table 3,) and all-cause death (N=7, 061, appendix Table 2) were determined using separate multivariable Cox-proportional hazards models. The % myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred were independent predictors of cardiac-death and all-cause death. For each 10% increase in % myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred, the hazard of cardiac-death increased by 34%, and 57% respectively. After adjustment for the listed covariates, compared to patients with normal stress PET MPI, the relative hazard of cardiac-death was 2.3 (95% CI=1.4–3.8, p=0.001), 4.2 (95% CI=2.3–7.5, p<0.001) and 4.9 (95% CI=2.5–9.6, p<0.0001), respectively, for patients with 0.1–9.9%, 10–19.9%, and ≥20% of the myocardium abnormal at stress (Figure 2A).

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Models Estimating Cardiac-death (N=6,036)

| CLINICAL MODEL | CLINICAL + PET MODEL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR | 95% CI for HR | P-Value | HR | 95% CI for HR | P-Value |

| Age in deciles | 2.00 | 1.72–2.33 | <0.0001 | 1.98 | 1.70–2.31 | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 0.49 | 0.35–0.68 | <0.0001 | 0.55 | 0.39–0.77 | 0.0005 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.99 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.31 |

| Hx Hypertension | 1.05 | 0.74–1.49 | 0.79 | 1.14 | 0.80–1.62 | 0.46 |

| Hx Diabetes | 2.28 | 1.65–3.14 | <0.0001 | 2.13 | 1.55–2.94 | <0.0001 |

| Hx Dyslipidemia | 0.70 | 0.51–0.96 | <0.0001 | 0.64 | 0.47–0.88 | 0.006 |

| Hx Smoking | 1.69 | 1.19–2.40 | 0.003 | 1.69 | 1.19–2.39 | 0.004 |

| Hx Angina | 0.69 | 0.50–0.93 | 0.016 | 0.73 | 0.54–1.00 | 0.05 |

| Beta-blocker | 1.33 | 0.96–1.84 | 0.09 | 1.26 | 0.87–1.67 | 0.16 |

| Rest heart rate* | 1.40 | 1.26–1.56 | <0.0001 | 1.34 | 1.19–1.50 | <0.0001 |

| Hx PCI | 1.47 | 1.01–2.13 | 0.04 | 1.34 | 0.91–1.941 | 0.13 |

| Hx CABG | 1.32 | 0.92–1.90 | 0.14 | 1.04 | 0.72–1.50 | 0.82 |

| % Myo ischemic * | 1.34 | 1.15–1.57 | 0.0003 | |||

| % Myo scarred* | 1.57 | 1.38–1.78 | <0.0001 | |||

| Comparison of the Clinical and Clinical + PET models for Cardiac-death | ||

|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL MODEL | CLINICAL+PET MODEL | |

| AIC | 2605 | 2556 |

| Chi square value | 221 | 275 |

| C-Statistic | 0.805 (0.772–0.838) | 0.839 (0.809–0.869) |

| IDI | 0.018 (0.01–0.03) | |

| Relative IDI | 0.336 (0.143–0.559) | |

| NRI-continuous | 0.540 (0.379–0.714) | |

| NRI-categories | 0.116 (0.021–0.210) | |

HR = hazard ratio; CI = confidence interval; yr = year; Hx = history of; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; Myo=myocardium; bpm= beats per minute.* per 10 unit change. AIC = Akaike information criterion, IDI = integrated discrimination improvement, NRI = net reclassification improvement.

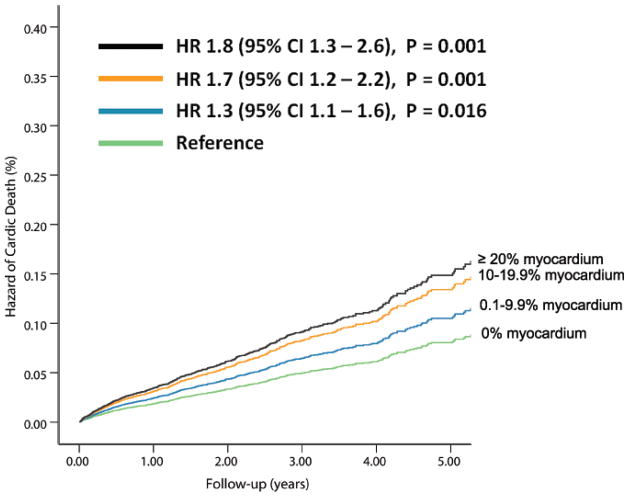

Figure 2. Risk-Adjusted Hazard of Events by % Abnormal Myocardium on Vasodilator Stress Rb-82 PET.

Hazard of cardiac-death (A, 6, 037 patients, N= 169 cardiac-deaths)and all-cause death (B, 7,061 patients, N=570 all-cause deaths) was lowest in patients with normal PET MPI and increased gradually in patients with minimal, mild, moderate or severe degrees of scan abnormality.

In 2, 101 patients with rest LVEF, Cox models including the clinical variables with rest LVEF and then adding the PET variables (% myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred), showed that a 10% points higher rest EF was associated with a lower hazard of cardiac-death (HR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.46–0.70, P<0.0001). After accounting for the clinical variables and rest LVEF, for each 10 % myocardium ischemic there was an 84% higher hazard of cardiac-death (HR 1.84, 95% CI: 1.40–2.41, P <0.0001), while for each 10% and myocardium scarred there a trend toward a 23% higher hazard of cardiac-death (HR 1.23, 95% CI: 0.96–1.56, P =0.09). The addition of % myocardium ischemic and scarred to the clinical model including LVEF resulted in an increment in model Chi square value from 110 to 127, P <0.0001 and an increment in model C statistic from 0.844 to 0.875 (P=0.05).

Multivariable Cox Models for the estimation of all-cause death

The % myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred were independent predictors of all-cause death (Appendix Table 2).

Incremental prognostic value of PET MPI using conventional and novel risk reclassification metrics

Tables 3 and 4, show the incremental value of PET MPI over clinical risk factors using conventional parameters of model fit: chi square value, model AIC value; model global performance: change in C-statistic, IDI and continuous NRI and model clinical value: NRI with categories. For cardiac-death, the addition of the % myocardium ischemic and scarred significantly improved the model fit as well as the global performance of the model. In contrast, the results for all-cause death (Appendix Table 2) also showed improved model fit and global performance, but, of a much smaller magnitude compared to cardiac-death.

Table 4.

Risk Reclassification for Risk in 6, 037 Subjects With and Without Cardiac-death

| Subjects with cardiac-death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET model | Overall | |||

| Clinical model | Risk Categories | |||

| Risk Categories | <1.0% | 1.0% – 2.9% | ≥ 3.0% | |

| <1.0% | 70.4 (88.9%) | 8.8 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) | 79.2 |

| 1.0% – 2.9% | 12.0 (17.7%) | 34.8 (51.4%) | 20.9 (30.9%) | 67.7 |

| ≥ 3.0% | 0 (0%) | 7.3 (42.6%) | 9.9 (57.4%) | 17.2 |

| Overall | 82.4 | 50.9 | 30.8 | 164.1 |

| Subjects without cardiac-death | ||||

| <1.0% | 3503.6 (96.2%) | 122.2 (3.4%) | 15 (0.4%) | 3640.8 |

| 1.0% – < 2.9% | 364 (23.1%) | 1075.2 (68.3%) | 135.1 (8.6%) | 1574.3 |

| ≥ 3.0% | 0 (0%) | 206.7 (31.4%) | 451.2 (68.6%) | 657.8 |

| Overall | 3867.6 | 1404.1 | 601.2 | 5872.9 |

NRI = Net reclassification improvement. NRI continuous = 0.540 (95% CI 0.379–0.714); NRI categories = 0.116 (95% CI 0.021–0.210). Table depicts predicted events rates at 2 years.

In order to estimate the incremental clinical prognostic value, we determined the net reclassification of risk after the addition of the PET MPI information (% myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred) to the baseline clinical information. As shown in the Table 4 (cardiac-death, N=6, 037), the majority of patients remained at the same risk level (diagonal values from left upper to the right lower cells), for the events and non-events.

Reclassification of cardiac-death

The addition of the % myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred to a baseline model with clinical factors resulted in significant clinical incremental value for prediction of cardiac-death. The model IDI was 0.018 (95% CI 0.01–0.03), with a relative IDI of 33.6 % (95% CI 14.3%–55.9%). The continuous NRI was 54.0 % (95% CI 37.9%–71.4%), for annual risk categories of < 1 %, 1.0–2.9% and ≥ 3.0%, NRI was 11.6 % (95% CI, 2.1% – 21%) (Table 4). The addition of % myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred to the clinical model more correctly reclassified cardiac-death in about 12% of patients. The majority of the reclassification was observed in the intermediate clinical risk group.

In patients with rest LVEF data, the addition of the % myocardium ischemic and % myocardium scarred to a baseline model with clinical factors and rest LVEF, resulted in significant clinical incremental value for prediction of cardiac-death. The IDI was 0.017 (0.002–0.037), and the relative IDI was 0.226 (0.029–0.467). The continuous NRI was 0.504 (95% CI 0.205–0.794) and for annual risk categories of < 1 %, 1.0–2.9% and ≥ 3.0%, NRI was 0.075 (95% CI, 0.008–0.149). The % myocardium ischemic and scarred provided incremental value to the clinical model which included rest LVEF and more correctly reclassified cardiac-death in 8% of patients.

For all-cause death, the NRI results also showed added value of risk classification with PET MPI, although the magnitude of reclassification was lower than for cardiac-death (Appendix Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The current report is the first multicenter registry to examine prognosis in 7, 061 subjects undergoing pharmacological stress Rb-82 PET MPI. In the largest study to date, our results demonstrate that for the prediction of cardiac-death and all-cause death, an abnormal PET MPI provides significant incremental prognostic value over the clinical factors. Patients with a severely abnormal stress PET MPI had almost a 5-fold higher hazard of cardiac-death compared to patients with a normal PET MPI, even after accounting for clinical risk markers. Also, an abnormal PET MPI along with clinical risk markers provided significant risk reclassification in 12% of patients, confirming the clinical utility of PET MPI. This study provides the initial strong evidence that the magnitude of scar and ischemia on PET MPI can be a powerful tool for risk reclassification of subjects with known or suspected CAD. Importantly, this multicenter registry provided an enriched cohort of patients with geographic diversity imaged on a variety of imaging devices making the results much more generalizable than prior single center studies.

Risk reclassification is a relatively novel concept that has been applied to the assessment of other risk markers such as calcium score(13), c-reactive protein(14 ) and more recently reported with SPECT MPI (15) and coronary flow reserve by quantitative PET MPI.(8,16,17) To our knowledge this is likely the first study assessing risk reclassification with rest and stress perfusion defects on PET MPI compared to clinical factors. By demonstrating significant risk reclassification for every 10% ischemic myocardium, this study confirms a threshold of >10% ischemic myocardium as significant for risk stratification with PET MPI, similar to that previously established with SPECT MPI.(18) The results of this study provide evidence that the magnitude of ischemia and scar on PET MPI provide for a significant improvement (large effect size based on a continuous NRI 0.540) (12) in clinical risk stratification; risk is reclassified more appropriately in 11.6 % of the patients for cardiac-death, potentially aiding in management decisions. Further, in exploratory analyses, it appears that the knowledge of magnitude of ischemia on PET MPI results in reclassification of 7.5% of patients compared to the clinical variables including rest LVEF. The NRI can provide an excellent measure for assessing the clinical utility of a novel risk marker.(11,15) The NRI value of a novel risk marker can be compared to that of another marker within the same patient cohort. However, direct comparison of the NRI values between different study cohorts may be challenging due to the inherent differences in the patient risk characteristics and the clinical variables used in the respective studies. Hence, whether the clinical utility of rest or stress perfusion defects by PET MPI is superior to or similar to that published with SPECT MPI on the basis of NRI cannot be definitively determined. Also, it is important to recognize that although reclassification of risk suggests that management and outcomes would be potentially altered based on the results of the PET MPI study, larger prospective clinical trials would be necessary to demonstrate changes in clinical management and outcome.

While several single center studies have shown that relative PET, quantitative PET MPI, and PET assessed coronary flow reserve(8,16,17) provide risk stratification for cardiovascular outcomes, data about improved risk reclassification with PET MPI are limited.(8,16) The current study demonstrates that relative PET MPI provides for improved risk reclassification of 12% of patients, over clinical variables, while, recent studies showed that coronary flow reserve assessed by quantitative PET MPI provides additional risk reclassification of between 10%–11% of patients.(8,16) Also, the addition of measures of atherosclerosis such as calcium score (19) or CT coronary angiography (20) may also provide additional risk stratification to relative PET MPI. However, it remains to be seen whether measures of coronary atherosclerosis provide incremental reclassification of risk compared to relative PET MPI.

PET MPI offers several clinical advantages compared to SPECT MPI(21); image quality is superior, test specificity for the diagnosis of obstructive CAD higher and identification of scar and ischemia is better with PET MPI. As shown recently, ischemia and scar can modulate the prognostic value of MPI (22). PET MPI is particularly advantageous in high clinical risk cohorts such as those undergoing pharmacological stress testing, and patients with heart failure or obesity.(21) Importantly, the incremental clinical value of PET MPI is attained at a significantly lower estimated effective radiation dose to the subjects (~2.0 to 3.7 mSv (23,24) with Rb-82 MPI compared to ~10–12 mSv with Technetium-99m MPI(25)), and at a much faster pace compared to SPECT MPI. However, when compared to SPECT, the evidence supporting the clinical utility of PET MPI is limited. Although the prognostic value of SPECT MPI has been described in several tens of thousands of patients, the prognostic value of PET MPI is only available in several thousands of patients. The results of the current study are critical to advance the field and guide more effective use of PET MPI in clinical practice.

Likewise, the prognostic value of CT coronary angiography is being currently established. However, while CT coronary angiography provides information about the nature and anatomic extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis, SPECT and PET MPI provide information about myocardial blood flow; PET MPI takes into account underlying CAD, collateral flow, myocardial adaptation to wall stress and other factors, and can also be used in patients with renal insufficiency.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This is a large multicenter registry comprised of patients from 4 medical centers with the attended strengths, limitations and biases. Cardiac-death was analyzed only in 6,037 patients. Renal failure was not included in this analysis, reproducibility of scan interpretation between the medical centers was not measured, the prognostic value of PET in patients without angina or dyspnea was not specifically studied. Also, LVEF was not available in all the subjects and inclusion of LVEF may potentially alter the relation between scarred myocardium and outcomes. Data on early revascularization was not available from all the centers, so we were not able to test whether patients with abnormal imaging findings would be more likely to benefit from revascularization. However, the inclusion of patients with early revascularization may serve to strengthen our results, since revascularization would be expected to attenuate the relation between PET MPI and clinical outcomes. Lastly, majority of the perfusion studies were scored visually, but one site used automated software analysis. Automated quantitation of MPI is well validated for risk assessment and comparable to visual analyses.(26) Yet, the multisite registry design overcomes the limitations inherent to data from single centers in terms of homogeneity of patient population and data spanning a decade of imaging, further expanding the diversity and generalizability of the study results. The large study cohort allowed us adequate power to study measures of risk reclassification, which would not be possible by data from any of the individual centers.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite widespread clinical use of PET MPI for its superior diagnostic accuracy and safety profile, the evidence for incremental risk stratification with PET MPI is limited. The results of this large multicenter registry demonstrate that in patients with known or suspected CAD, Rb-82 PET MPI provides powerful and incremental risk stratification. Assessment of the magnitude of ischemia and scar on PET MPI adds to the reclassification of risk for cardiac-death in 1 in 9 patients undergoing clinical PET MPI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by an unrestricted grant from Astellas Pharma Global Development, Bracco Diagnostics, Inc., National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant (K23HL092299) and by a program grant from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (#PRG6242).

Abbreviations

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- MPI

Myocardial perfusion imaging

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- BMI

Body mass index

- Rb-82

Rubidium 82

- IDI

Integrated discrimination improvement

- NRI

Net reclassification improvement

- HR

hazard ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

Footnotes

Disclosures: Sharmila Dorbala: Research grants: Astellas and Bracco diagnostics, >10K; Consultant/Advisory Board: Astellas <10k; Honoraria: Medxel <10k.

Marcelo F. Di Carli: Research Grants.

Rob S. Beanlands: Research grants: Lantheus Medical Imaging, GE Healthcare, MDS Nordion > 10K; Consultant/advisory board: Lantheus Medical Imaging; Jubilant Draximage < 10K.

Michael E. Merhige: Speakers Bureau: Bracco Diagnostics <10K, Honoraria: Positron Group <10K, Medical Director, Positron group >10K

Brent A. Williams: Collaborator on several small research grants <10K

James K. Min: Speakers Bureau: Bracco Diagnostics <10K; Ownership interest: TC3; Consultant/Advisory Board: GE Healthcare/Edwards Life sciences

Daniel S. Berman: Research grants: Lantheus Medical Imaging, Siemens, Cardium Therapeutics Inc >10K; Honoraria: Spectrum Dynamics <10 K; Consultant/Advisory Board: Bracco diagnostics <10K; Royalties- Cedars Sinai Software > 10K.

Leslee J. Shaw: Research grants: Astellas and Bracco diagnostics, >10K

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marwick TH, Shan K, Patel S, Go RT, Lauer MS. Incremental value of rubidium-82 positron emission tomography for prognostic assessment of known or suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:865–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshinaga K, Chow BJ, Williams K, et al. What is the prognostic value of myocardial perfusion imaging using rubidium-82 positron emission tomography? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1029–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sdringola S, Loghin C, Boccalandro F, Gould KL. Mechanisms of progression and regression of coronary artery disease by PET related to treatment intensity and clinical events at long-term follow-up. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merhige ME, Breen WJ, Shelton V, Houston T, D’Arcy BJ, Perna AF. Impact of myocardial perfusion imaging with PET and (82)Rb on downstream invasive procedure utilization, costs, and outcomes in coronary disease management. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1069–76. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lertsburapa K, Ahlberg AW, Bateman TM, et al. Independent and incremental prognostic value of left ventricular ejection fraction determined by stress gated rubidium 82 PET imaging in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2008;15:745–53. doi: 10.1007/BF03007355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorbala S, Hachamovitch R, Curillova Z, et al. Incremental prognostic value of gated Rb-82 positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion imaging over clinical variables and rest LVEF. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:846–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida K, Gould KL. Quantitative relation of myocardial infarct size and myocardial viability by positron emission tomography to left ventricular ejection fraction and 3-year mortality with and without revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:984–97. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90407-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziadi MC, Dekemp RA, Williams KA, et al. Impaired myocardial flow reserve on rubidium-82 positron emission tomography imaging predicts adverse outcomes in patients assessed for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:740–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams BA, Dorn JM, LaMonte MJ, et al. Evaluating the Prognostic Value of Positron Emission Tomography Myocardial Perfusion Imaging Using Automated Software to Calculate Perfusion Defect Size. Clin Cardiol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/clc.22058. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbons RJ, Chatterjee K, Daley J, et al. ACC/AHA/ACP-ASIM guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:2092–197. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–72. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30:11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polonsky TS, McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA. 2010;303:1610–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson PW, Pencina M, Jacques P, Selhub J, D’Agostino R, Sr, O’Donnell CJ. C-reactive protein and reclassification of cardiovascular risk in the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:92–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.831198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw LJ, Wilson PW, Hachamovitch R, Hendel RC, Borges-Neto S, Berman DS. Improved near-term coronary artery disease risk classification with gated stress myocardial perfusion SPECT. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:1139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2011;124:2215–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukushima K, Javadi MS, Higuchi T, et al. Prediction of short-term cardiovascular events using quantification of global myocardial flow reserve in patients referred for clinical 82Rb PET perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:726–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.081828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072790.23090.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schenker MP, Dorbala S, Hong EC, et al. Interrelation of coronary calcification, myocardial ischemia, and outcomes in patients with intermediate likelihood of coronary artery disease: a combined positron emission tomography/computed tomography study. Circulation. 2008;117:1693–700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Curillova Z, et al. Relationship between CT coronary angiography and stress perfusion imaging in patients with suspected ischemic heart disease assessed by integrated PET-CT imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007;14:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Carli MF, Hachamovitch R. New technology for noninvasive evaluation of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;115:1464–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.629808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hachamovitch R, Rozanski A, Shaw LJ, et al. Impact of ischaemia and scar on the therapeutic benefit derived from myocardial revascularization vs. medical therapy among patients undergoing stress-rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1012–24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senthamizhchelvan S, Bravo PE, Esaias C, et al. Human biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 82Rb. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1592–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.077669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter C, Ziadi M, Etele J, Hill J, Beanlands R, deKemp R. New effective dose estimates for Rubidium-82 based on dynamic PET/CT imaging in humans. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:282P. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Einstein AJ, Moser KW, Thompson RC, Cerqueira MD, Henzlova MJ. Radiation dose to patients from cardiac diagnostic imaging. Circulation. 2007;116:1290–305. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.688101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berman DS, Kang X, Van Train KF, et al. Comparative prognostic value of automatic quantitative analysis versus semiquantitative visual analysis of exercise myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1987–95. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.