Abstract

Viremic controllers (VC) and elite controllers/suppressors (ES) maintain control over HIV-1 replication. Some studies suggested that control is a result of infection with a defective viral strain while others suggested host immune factors play a key role. Here we document two HIV-1 transmission pairs: one consisting of a patient with progressive disease and an individual who became an ES, and the second consisting of a patient with progressive disease and a VC. In contrast to another ES transmission pair, virus isolated from all patients was fully replication competent. These data suggests that some VC and ES are infected with HIV-1 isolates that replicate vigorously in vitro and are able to cause progressive disease in vivo. These data suggest that host factors play a dominant role in control of HIV-1 infection, thus it may be possible to control fully pathogenic HIV-1 isolates with therapeutic vaccination.

Introduction

HIV-1 infection is usually characterized by intense viral replication and progressive CD4+ T cell depletion. However, in defined subsets of infected individuals, the disease course is more benign. Long term nonprogressors (LTNPs) are HIV-1 infected individuals who, in the absence of therapy, maintain stable CD4+ T cell counts greater than 500 cells/μl for longer than seven years. This clinical definition is independent of the level of viremia, which can vary greatly in this subset [1]. Another subset, viremic controllers (VCs), maintain low levels of viremia (<2000 copies of HIV-1 RNA/ml, detectable by commercially available viral load testing) in the absence of therapy. A third subset, elite suppressors (ES), suppress viremia to below the clinical limit of detection (50 copies/ml). ES represent less than 1% of the HIV-1 infected population [1].

Defective or attenuated HIV-1 isolates were initially thought to be responsible for the LTNP phenotype. Deletions in viral genes such as nef have been shown to facilitate control of HIV-1 infection [2–10], and rare, stable polymorphisms in HIV-1 isolates from some ES have been documented [11]. It has been hypothesized that these defective isolates may explain the clinical status of these patients. However, it has become increasingly clear that viral factors alone cannot explain the variable nature of HIV-1 infection. Several studies have shown that replication-competent HIV-1 can be isolated from ES [12–14]. Full genome sequence analysis of replication-competent viral isolates from ES revealed no large deletions [12], and ongoing viral replication and evolution in ES have been documented in recent studies [15–17]. Taken together, these data suggest that in some cases, infection with attenuated virus cannot explain elite suppression. There is an increasing appreciation for the role played by the host immune response in this phenotype. The HLA-B*57 allele group is overrepresented in ES [18–24], and the HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cell response in these patients is generally superior to that seen in patients with progressive disease [20, 25–27].

Data supporting a model of host control of viral replication comes from a previous study by our group examining an HIV-1 transmission pair. Virus was transmitted from an HLA-B*57 positive patient who developed AIDS to a recipient who was positive for both HLA-B*57 and HLA-B*27 group alleles and who subsequently became an ES. The viruses infecting both individuals were shown to be closely related by phylogenetic analysis, but the virus isolated from the ES displayed a partial replication defect, and mutations in gag were shown to contribute to this viral attenuation. It was hypothesized that selective pressure from HIV-specific CTLs caused evolution of the transmitted virus and maintained key escape mutations in HLA-B*27 and HLA-B*57 gag epitopes that resulted in viral attenuation [28]. However, it is possible that selective pressure from the chronic progressors’ CD8+ T cells resulted in mutations in HLA-B*57 epitopes early in his disease course. Some of these mutations, such as Gag T242N, have a significant fitness cost [29, 30], thus the virus may have been attenuated prior to transmission, which could have contributed to the elite control of viral replication.

We now present two additional HIV-1 transmission pairs each, consisting of a patient with progressive disease and a patient who controlled viral replication. These cases differ from the previously reported case in that viruses isolated from all patients were shown to replicate equally well in vitro, suggesting that host factors can control replication of fully pathogenic HIV.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The first transmission pair consists of a 40 year old male, a chronic progressor (CP1), and a 37 year old female, a viremic controller (VC1). Infection was first documented in CP1 in 1996, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) was initiated in 1998. The patient had a long history of poor adherence to multiple regimens, and his viral load fluctuated dramatically, as shown in Figure 1, A. CD4+ T cell counts progressively declined to the current level of 200 cells/μl. His partner, VC1, was also diagnosed with HIV-1 infection in 1996. She was originally started on ART for unknown reasons in 1998. Her baseline CD4 count was 741 cells/ul, and her baseline viral load was 1184 copies/mL. She was taken off treatment in 2000 due to poor adherence (Figure 1, B). Since that time, plasma HIV-1 RNA has ranged from < 50 copies/ml to 400 copies/ml, and she has maintained an average CD4+ T cell count of 921 cells/μl.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Natural history of infection between transmission pairs. CD4+ T cell counts (blue) and viral load (red) are observed over time for (A) CP1, (B) VC1, (C) CP2, and (D) ES38. Open squares denote viral loads below the limit of detection of the assay. Periods of antiretroviral therapy are indicated by shaded regions for CP1, CP2 and VC1.

The second pair consists of a 35 year old male, a chronic progressor (CP2), and a 21 year old female who became an ES (ES38). CP2 was found to be infected with HIV-1 in June 2010, and has since maintained plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of approximately 30,000 copies/ml. His CD4+ T cell count reached a nadir of 273 cells/ul before initiation of ART (Figure 1, C). ES38, who tested negative for HIV-1 in 2008, was also diagnosed with HIV-1 infection in June, 2010 but has maintained a plasma HIV-1 RNA level of less than 50 copies/ml and an average CD4+ T cell count of 935 cells/ul (Figure 1, D).

Sequence Analysis Confirms Transmission

To confirm transmission of virus between the relevant patients, virus was cultured from each patient’s CD4+ T cells with a sensitive co-culture assay, as previously described [34]. Full length sequence analysis was performed, and the resulting genomes were compared to each other and to the consensus B clade sequence. No large deletions, premature stop codons, frame shifts, or other gross defects were seen in isolates cultured from any of the patients.

The number of synonymous nucleotide changes, as well as a number of amino acid differences, between transmission partners, are shown in Table 1. Phylogenetic analysis was performed, and full length env sequences from both transmission pairs were compared to other HIV-1 env sequences obtained from the Los Alamos database (Figure 2, A). For both the CP1/VC1 and CP2/ES38 pair, sequences within a pair were more similar to each other than to other B clade isolates, reflecting a common ancestor consistent with viral transmission within the pairs. Representative sequence alignments (Figure 2, B) demonstrate that the sequences within the transmission pairs are closely related. There are rare sequence polymorphisms unique to each transmission pair. Comparative alignments of sequences from CP1 and VC1 revealed unique polymorphisms in tat at nucleotide positions 100 and 101, where aspartic acid (D) is followed by a histadine (H). The combination of these two amino acids at these positions occurs in only 5.3% of B clade isolates in the Los Alamos HIV sequence database (Figure 2, B). This strongly suggests that the two patients are indeed a transmission pair. Similarly, unique polymorphisms were seen in rev and vpu. Unique polymorphisms in tat also confirmed transmission between CP2 and ES38: isolates from both patients had a combination of a phenylalanine (F) followed by a histadine (H) at positions 100 and 101, which is present in less than 1% of B clade isolates in the Los Alamos database (Figure 2, B).

Table 1.

Differences in viral isolates in each transmission pair

| Sequence Analysis: CP1 Compared to VC1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Synonymous Mutations | Amino Acid Changes |

| Pol | 31 | 7 |

| Gag | 23 | 24 |

| Rev | 1 | 7 |

| Vpr | 2 | 7 |

| Vpu | 2 | 12 |

| Tat | 2 | 8 |

| Env | 53 | 125 |

| Nef | 14 | 15 |

| Vif | 9 | 8 |

| LTR | 2 | |

| Sequence Analysis: CP2 Compared to ES38 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Synonymous Mutations | Amino Acid Changes |

| Pol | 9 | 7 |

| Gag | 10 | 7 |

| Rev | 2 | 5 |

| Vpr | 3 | 2 |

| Vpu | 0 | 0 |

| Tat | 2 | 4 |

| Env | 6 | 39 |

| Nef | 8 | 4 |

| Vif | 6 | 8 |

| LTR | 2 | |

Figure 2.

Analysis of viral sequences confirms transmission between patients. (A) Phylogenetic tree of env sequences from the CP1/VC1 and CP2/ES38 transmission pairs. Phylogenies were estimated by using a “classical” approach, functioning under maximum-likelihood optimality criterion. Representative B clade isolates are shown, and A, C and D outgroups are denoted. (B) Tat amino acid sequences for CP1 and VC1 (top) and Tat amino acid sequences for CP2 and ES38 (bottom) are compared to consensus B clade sequence. Rare polymorphisms in Tat, shared within each transmission pair, are highlighted. (C) Fitness of viral isolates from transmission pairs. CD4+ T cells from healthy donors were infected, and production of viral p24 was measured over time. Error bars represent standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. On the left, growth kinetics of replication competent isolates from CP1 (blue) and VC1 (red) are compared to BaL (purple), and on the right growth kinetics of replication competent isolates from CP2 (orange) and ES38 (brown) are compared to Ba-L (purple).

No Significant Differences in Viral Fitness between Isolates

Previous studies have suggested that attenuation in infecting viruses could explain the clinical outcome of infection [2–11]. In addition, in a previously reported transmission pair, there was clear viral attenuation in the isolate cultured from the ES, which could have contributed to elite suppression [28]. To determine if differences in viral fitness could explain the status of both transmission pairs, we isolated replication-competent virus from the latent reservoir of each patient. Multiple isolates were obtained from each patient, and viral replication was compared using healthy donor CD4+ T cells. For the first transmission pair, viral isolates from VC1 were as fit as isolates from CP1 (Figure 2, C). The second transmission pair showed similar results, with no differences in viral fitness seen in isolates cultured from CP2 and ES38 (Figure 2, C). All viral isolates replicated as efficiently as the HIV-1BAL reference strain.

The Role of Host Factors in the Control of Viral Replication

Since no differences were seen in the replication of viruses from each member of the two transmission pair, and since all viruses were as fit as the reference strain HIV-1BaL, we sought to determine whether cellular factors could be playing a predominant role in determining the clinical phenotype. Subjects who are heterozygous for the delta 32 mutation in CCR5 have slower progression of HIV-1 disease [35]. The CCR5 gene was analyzed by PCR, and all patients were determined to have two wild type CCR5 alleles.

HLA-typing was also performed on each patient. It is interesting to note that ES38 is HLA-B*57:03 positive. This is a protective allele group that is overrepresented in ES [18–24]. No known protective HLA alleles were present in VC1, CP1, or CP2 (Table 2). A single nucleotide polymorphism associated with the HLA-C promoter (rs9264942) has also been implicated in control of viral replication in a genome wide association study [36]. Of the four patients, none were homozygous for the protective allele (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cellular Factors of Viral Control

| Transmission Pair 1 | Transmission Pair 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP1 | VC | CP2 | ES | |

| HLA-A | A*23 | A*23, A*29 | A*01, A*33 | A*02, A*74 |

| HLA-B | B*15, B*35 | B*07, B*39 | B*08, B*35:01 | B*52:01, B*57:03 |

| HLA C SNP rs9264942 | T/T | T/C | T/T | T/T |

| HLA-B Bw4-80Ile | − | − | − | + |

| KIR3DS1 | − | − | − | − |

| CCR5 | WT/WT | WT/WT | WT/WT | WT/WT |

Natural killer cells have been implicated in delaying the progression of HIV-1 disease. The interaction between the NK cell receptor KIR3DS1 and HLA-Bw4-80Ile motif has been shown to be protective [37]. We sought to determine if our patients possessed this protective combination. None of our patients were positive for the KIR3DS1 activating allele (Table 2), and only ES38 was positive for an HLA-B Bw4-80Ile motif.

CD8+ T cell response in Elite Suppression

In order to determine how pressure from HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphyocyte (CTL) responses might have led to differences in viral evolution in the patients, we performed IFN-γ ELISPOT assays to determine which epitopes were targeted in Gag and Nef. The epitope DQ15 (Gag 219 to 233) was targeted by both CP1 and VC1, but mutations in this region were observed only in isolates from CP1 (Figure 3). Similarly, a mutation was present in NP15 (Gag 331 to 346), an epitope targeted by VC1, indicating potential virologic escape in this subject.

Figure 3.

Gag sequences from VC1 and CP1. Patient-specific CTL epitopes were identified by IFN-γ ELISPOT, and are highlighted for each patient. Numbering indicates amino acid position in Consensus B Clade Gag.

CP2 and ES38 each targeted several epitopes in Gag (Figure 4). Interestingly, ES38 made responses to peptides that contained previously characterized HLA-B*57 restricted epitopes, and both ES38 and CP2 had mutations in HLA-B*57 restricted Gag and Nef epitopes, including L90V and H121N in Nef and I147L, G248A, I247V and E312D in Gag. Additionally, an S173T mutation that has been seen in HLA-B*57 individuals [39] was present adjacent to the immunodominant HLA-B*57-restricted KF11 epitope (gag 162–172) in both patients. The presence of these mutations in both patients, including CP2 who is not positive for HLA-B*57 (Table 2), would suggest that either CP2 was originally infected with virus from an HLA- B*57 positive patient, or that ES38 transmitted virus to CP2 after these mutations developed. Phylogenetic analysis of clonal nef sequences (figure 5A) amplified from resting CD4+ T cells from both patients was performed, but the results could not definitively distinguish between the two hypotheses.

Figure 4.

Gag and Nef Sequences from CP2 and ES38. Patient-specific CTL epitopes were identified by IFN-γ ELISPOT, and are highlighted for each patient. HLA-B*57-restricted epitopes are indicated. Numbering indicates amino acid position in Consensus B Clade Gag or Nef.

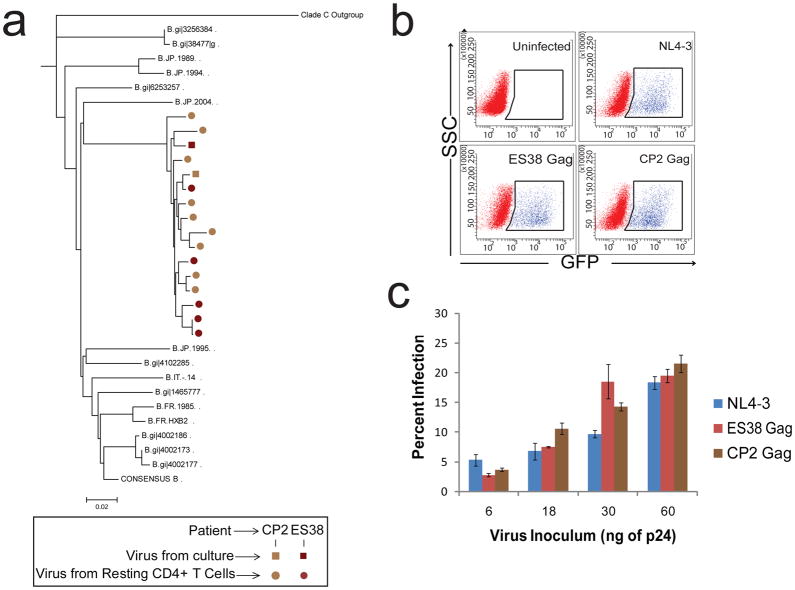

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis and gag fitness in virus from ES38 and CP2. (A) Phylogentic tree of clonal nef sequences isolated from resting CD4+ T cells (circles) and replication competent virus isolates for reference. Phylogenies were estimated by using a “classical” approach, functioning under maximum-likelihood optimality criterion. Other representative B clade isolates, consensus B clade nef, and the clade C outgroup are denoated. Fitness of patient-specific viral gag. (B) Representative FACS plots showing GFP expression indicates infection with single cycle, pseudotyped virus. (C) Percent infection with various volumes of pseudotyped virus containing gag from ES38 (red), CP2 (brown), and wild type NL4-3 (blue) was determined and repeated for three donors, producing similar results. Approximate levels of p24 in each infectious volume are shown, estimated and normalized based on NL4-3. Infection of healthy donor CD4+ T cells was normalized by transfection efficiency. Error bars represent standard error of the means from three independent experiments.

It has been shown that some escape mutations in HLA-B*57 restricted epitopes in Gag have a negative effect on viral fitness (30–31) and may contribute to elite control. ES38 did not possess the T242N mutation, which is known to revert when transmitted to HLA-B*57-negative individuals [40–41]. Nonetheless, to determine whether other mutations in this gene had significant effects on fitness, we cloned the gag genes from CP2 and ES38 and compared infection of healthy donor CD4+ cells with these isolates to infection with NL4-3. There was no significant difference in the infectivity of virus expressing patient-derived Gag (Figure 5B, C). Thus the difference in the level of viral control in these patients cannot be attributed to differences in viral fitness. Additionally, the infection levels of both viruses was similar to that of the reference strain, further suggesting that ES38 was exerting control over a virus that replicates as well in vitro as does virus from a patient with progressive disease. Taken together, these data suggest that viral fitness is not the determining factor that explains differences in the clinical outcome seen in the patients in both of the reported transmission pairs.

ES38 was positive for the HLA-B*57 allele, which has been associated with elite control of HIV-1 replication in many studies. However, VC1 does not have any known protective HLA alleles, therefore we compared multiple aspects of her HIV-1-specific immune response to those seen in CP1. As shown in Figure 6A, stimulation of PBMCs with overlapping Gag peptides resulted in a substantially higher percentage of IFN-γ expressing HIV-specific CD4+ T cells that co-expressed IL-2 in VC1 compared to CP1, consistent with prior studies showing the preservation of IL-2 secretion in aviremic individuals [42–46]. CD8+ T cell responses have been intensely studied in ES [19–28]. It has been shown that CTLs from ES are more likely to upregulate cytolytic granules containing perforin and granzyme B (20, 25, 27). These cells are also more likely to co-express IFN-γ and TNF-α [47], which is a known correlate of cytotoxic activity [48]. IFN-γ expressing HIV-specific CD8+ T cells from VC1 fit this profile and co-expressed more perforin and TNF-α in response to stimulation with Gag and Nef peptides than did CD8+ T cells from CP1 (Figure 6B–D). In order to determine whether this phenotype was associated with actual inhibition of viral replication, a suppression assay was performed. Because CP1 was on HAART, CD4+ T cells from both patients were incubated for a week prior to infection with pseudotyped virus. Freshly isolated CD8+ T cells from CP1 had no effect on CD4+ T cell infection whereas CD8+ T cells from VC1 substantially reduced the percentage of infected cells (Figure 6E). In a traditional inhibition assay where there was no pre-incubation of CD4+ T cells prior to stimulation and infection, CD8+ T cells of VC1 were seen to be as effective as those from a cohort of HLA-B*57 ES in controlling replication-competent virus in vitro, whereas CD8+ T cells from patients with progressive disease and uninfected individuals had low inhibitory activity (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Differential HIV-specific CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell cytokine response. (A) Stimulation of patient PBMCs cells isolated directly ex vivo with overlapping Gag peptides. The percent of IFN-γ expressing HIV-specific CD4+ T cells that co-expressed IL-2 is shown for VC1 and CP2. A minimum of 250,000 total events were analyzed by FACS. (B) Representative FACS plots showing the stimulation of PBMCs isolated from VC1 and CP1. The plots are gated on all CD8+ T cells, and the percentage of IFN-γ positive cells that co-expressed TNF-α or perforin are indicated in the top right quadrant. Quantification of the percentage of IFN-γ expressing CD8+ T cells that co-expressed perforin, TNF-α, or both perforin and TNF-α after stimulation with patient-specific Gag (C) or Nef (D) peptides are shown for both VC1 and CP1. A minimum of 250,000 total events were analyzed by FACS. Comparative CD8+ T cell inhibition of viral replication. (E) CD4+ T cells from VC1 and CP1 were infected with GFP expressing recombinant NL4-3 virus. CD4+ T cells were cultured alone or with autologous CD8+ T cells at a 1:1 ratio. Percent infection was measure five days after infection by FACS analysis. (F) CD4+ T cells from 4 Healthy Donors (D1–4), an untreated Viremic patient, 6 ES, and VC1 were infected with GFP expressing replication-competent NL4-3 virus. CD4+ T cells were cultured alone or with autologous CD8+ T cells at a 1:1 ratio. Percent inhibition was quantified 5 days after infection.

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms of control of viral replication in VC and ES may lead to effective immunotherapy of HIV-1 infection. Determining the role of viral fitness versus host factors in these patients is critical because it bears directly on the fundamental mechanism of elite control of HIV-1 replication. Unfortunately, isolating replication-competent virus from ES has proven to be extremely challenging. As a result, many studies have focused on the analysis of proviral and/or plasma sequences from ES. Some studies have not found any deleterious mutations or large deletions [49–50], whereas others have reported significant deletions (2–11) and/or reductions in fitness of recombinant viruses expressing viral genes amplified from ES [52–54]. The results of these studies are limited by the fact that many proviral clones are not replication-competent and the viruses in the plasma of ES typically contain attenuating escape mutations not found in virus archived in resting CD4+ T cells [55]. Full genome sequence analysis has been performed for less than ten replication-competent isolates cultured from ES CD4+ T cells [12, 28, 56, 57], and there has been only one documented case of viral transmission from a CP to an ES described in the literature [28]. The two transmission pairs presented here are unique because they stand in contrast to the previously reported transmission pair: in this study, viruses isolated from both VC1 and ES38 were fully replication competent and as fit as viruses isolated from their partners with progressive HIV-1 disease. In the previous study, the ES was found to have an attenuated viral isolate. While we hypothesized that the diminished fitness in this patient was due to escape mutations that developed in response to strong selective pressure from CTL, it is also possible that viral attenuation preceded transmission and contributed to elite suppression [28]. However, in this report, we have shown for the first time that replication-competent isolates obtained from patients who controlled viral replication had no evidence of attenuation and had the potential to cause progressive disease in vivo. This strongly suggests that in some cases elite suppression is not the result of infection with attenuated viruses. While ES38 is HLA-B*57:03 positive, no other known cellular factors could explain viral control in either of these transmission pairs. The HLA-C related SNP and the delta 32 CCR5 mutation that confer relative protection against HIV-1 infection, were not present in any of our patients, and all patients lacked the combination of KIR3DS1 and protective HLA-B alleles. CD8+ T cells have been extensively studied in control of HIV-1 infection, and strong evidence supports their key role in delaying disease progression [20, 25, 26, 27]. While we were unable to perform detailed HIV-specific CD8+ T cell analysis in ES38 due to a lack of cells, it is likely that HIV-specific HLA-B*57-restricted CTL played a role in elite suppression of viral replication. VC1 did not have any known protective HLA allele, but, unlike CP1, she had polyfunctional HIV-specific CD4+ T cells, and her HIV-specific CD8+ T cells expressed substantial levels of perforin and TNF-α upon activation and were as effective at inhibiting HIV-1 replication as CD8+ T cells from many HLA-B*57 positive ES. Thus, differences in CD8+ T cell function can probably explain the difference in clinical outcomes seen in these patients.

These data support the hypothesis that ES are infected with virus that replicates as well as virus that causes progressive disease, and a combination of host immune factors, unique to ES, enables control of viral replication. While infection with an attenuated virus can increase the chance of early and prolonged control of viral replication, this study and others supports a model in which host factors play a dominant role in determining the clinical outcome of infection. These results are consistent with the macaque model of elite control in which animals with protective MHC alleles are capable of controlling fully replication-competent laboratory strains of SIV [reviewed in 58]. Intriguingly, in two distinct elite monkey models, depletion of CD8+ T cells with monoclonal antibodies results in the transient loss of control of viral replication, [59, 60] implying that these cells play a major role in elite suppression.

Importantly, these data suggest that ES have a unique capacity to restrict viral replication, independent of the fitness of the infecting virus. Our sequence analysis suggests that ES31 may have infected CP2 who then went on to develop a rapid decline in his CD4+ T cell count. Overall, the data presented here provides the strongest evidence to date that host factors rather than viral fitness determines clinical outcome. Thus, by identifying the contribution of individual host factors, the mechanism of elite suppression could form the basis for a therapeutic vaccine for HIV-1.

Methods

Patient Consent

All patients were provided written, informed consent, and the handling of all patient samples was in accordance with the policies dictated by the Johns Hopkins University regulations.

Virus Isolation and Sequence Analysis

Culture of replication-competent virus and full genome sequence analysis of proviral and plasma virus were performed performed using a modified, highly sensitive co-culture assay [12]. Clonal nef sequences were amplified from resting CD4+ T cells as previously described [16]. Classical, maximum likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic analysis were performed as described previously [31]. The nested primers used in the study are as follows: LTR1 out (cacacaaggctayttccctga), LTR2 out (TCCYCYTGGCCTTAACCGAAT); LTR3 inner (ACTGTCTAGATGGATGGTGCTWCAAGYTAGT), LTR4 inner (ACTGCTCGAGTCCTTCTAGCCTCCGCTAGTC); 5 gag Outer (GCGAGAGCGTCAGTATTAAGC), 3 gag fullout3.2ext (TCTTTATCTAAGGGAACTGAAAAATATGCATC); 5 gag In (GGGAAAAAATTCGGTTAAGGCC), 3 gag In (CGAGGGGTCGTTGCCAAAGA); 5 outer FL (GCCCCTAGGAAAAAGGGCTGTTGG), 3 Outer FL (CCTTGCCCCTGCTTCTGTATTTCTGC); 5 Inner FL (TGCAGGGCCCCTAGGAAAAAGGGCTG), 3 Inner FL (CATGTACCGGTTCTTTTAGAATCTCCCTGT), 5 Integrase outer (ACTCCATCCTGATAAATGGACAG), 3 Integrase outer (AATCCTCATCCTGTCTACTTGCC); 5 Integrase inner (GAAAATTGAATTGGGCAAGTC), 3 Integrase inner (CCACACAATCATCACCTGCC); Accessory outer 1 (CGGGTTTATTACAGGGACARCARA), Accessory outer 2 (GGCATGTGTGGCCCARAYATTAT); Accessory inner 1 (GGTGAAGGGGCAGTAGTAATACAA), Accessory inner 2 (CCCATAATARACTGTGACCCACAA); 5 Env outer (ATGGCAGGAAGAAGCGGAGACAG), RT4.2 (GCTCAACTGGTACTAGCTTGAAGCACC); 5 Env Inner (GATAGACGCGTAGAAAGAGCAGAAGACAGTGGCAATG), 3 Env Inner (CCTTGTGCGGCCGCCTTAAAGGTACCTGAGGTCTGACTGG); 5 Nef Outer (GTAGCTGAGGGGACAGATAGGGTTAT), 3 Nef Outer (GCACTCAAGGCAAGCTTTATTGAGGC); 5 Nef Inner (CGTCTAGAACATACCTAGAAGAATAAGACAGG), 3 Nef Inner (CGGAATCCGTCCCCAGCGGAAAGTCCCTTGTA).

Viral Fitness Assay

Viral fitness was analyzed as described previously [12]. PBMCs from healthy donors were cultured for two days in the presence of IL-2 and PHA. CD4+ T cells were isolated (MACS, CD4+ T cell isolation Kit) and infected by spinoculation [32] (1200×g for 2 hours) with equal quantities (200ng/mL) of p24 from primary patient isolates, and with HIV-1BAL as a reference strain. Supernatant samples were taken over the course of 7 days. Viral replication was quantified using p24 ELISA (Perkin Elmer).

To study the effect of mutations in HLA-B*57 epitopes on gag fitness, gag from patient viral isolates was amplified by PCR. The resulting amplicon was digested with BSSHII and SbfI restriction enzymes and ligated into a previously described pNL4-3-ΔEnv GFP NL43dE vector [33]. The pNL4-3-ΔEnv GFP NL43dE vector with patient-specific gag was transformed into Stbl-3 cells (Invitrogen) to amplify, and co-transfected into 293T cells with an X4 Env plasmid to produce single round replication pseudovirus expressing patient specific gag. After a three day transfection, cellular debris were removed by centrifugation and filtration through Steriflip filters (Millipore). Virus was collected by ultracentrifugation at 1,200 × g for two hours, at 25° C. CD4+ T cells from healthy donor PBMCs were isolated by magnetic bead separation (Miltenyi), and were infected by spinoculation with NL4-3 (control), ES31-gag and CP2-gag pseudoviruses. Infection was analyzed after 3 days of infection by measuring green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression using a flow cytometer. The results were normalized by transfection efficiency.

Genetic Polymorphisms

HLA-A and HLA-B locus allele identification was performed as previously described (12). CCR5 from all patients was amplified from genomic DNA using gene specific primers. The presence or absence of the CCR5 Δ32 mutation was determined by relative size of the resulting PCR fragment. HLA-C single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping (rs9264942) was performed utilizing the Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR System allelic discrimination assay, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Primers and probes were developed by Custom TaqMan SNP Genotyping assays (ABI). Determination of the KIR3DS1 and HLA-B Bw4-80Ile allele was performed using the Olerup SSP 104.101 KIR Genotyping 12 Lot71E and 104.201 KIR ligand genotyping Lot85E kits, following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Immunologic Assays

Cytokine expression was determined by an intracellular cytokine staining assay as previously described (28). PBMCs were stimulated overnight with either HIV-1 Gag Nef peptides at a concentration of 5 ug/mL. For CD8+ T cell analysis, patient-specific Gag or Nef peptides determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT were used. For CD4+ T cell cytokine analysis, overlapping peptides spanning the entire amino acid sequence of B clade consensus Gag were used. Conjugated antibodies specific for perforin (Diaclone Research) IL-2 (BD Biosciences), INF-γ (BD Biosciences), and TNF-α (BioLegend) were used to examine cytokine expression by flow cytometry.

The Cytolytic T cell effect for VC1 compared to healthy donors, viremic patients and ES was determined by a CD8 suppression assay. PBMCs were isolated from patients, and CD8+ T cells were positively selected using Miltenyl magnetic beads (MACS, CD8+ T cell Isolation kit). CD8+ T cells were depleted of CD16+ cells (Invitrogen, Dynal Beads) to remove contaminating NK cells. CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection using Miltenyi magnetic beads. Purity of depletion was analyzed by flow cytometry. CD4+ T cells were infected by spinoculation at 1200×g for 2 hours with replication competent NL4-3 virus, in which GFP is engineered into nef. Autologous CD8+ T cells were added at a 1:1 ratio to CD4+ T cells, and infection between cultures with and without CD8+ T cell addition were compared. FACS analysis was performed 5 days after infection.

To compare cytolytic T cell effects between VC1 and CP1, PBMCs were isolated and cultured for three days in stimulating media. CD4+ T cells were isolated after three days, and maintained in stimulating media for another four days in order to diminish the inhibitory effect of the antiretroviral drugs that CP1 was on. The CD4+ T cells were spinoculated at 1200×g for 2 hours with single cycle pseudotyped NL4-3 virus. This virus was used to minimize the differences in the amount of replication that occurred in the patients’ CD4+ T cells. Autologous CD8+ T cells, isolated directly ex vivo, were added at a 1:1 ratio to CD4+ T cells, and infection between cultures with and without CD8+ T cell addition. FACS analysis was performed five day after infection.

To produce the replication competent NL4-3, the pNL4-3-ΔNef GFP vector was transformed into Stbl-3 cells (Invitrogen) to amplify, and transfected into 293T cells to produce pseudovirus. After a three day transfection, cellular debris were removed by centrifugation and filtration through Steriflip filters (Millipore). Virus was collected by ultracentrifugation at 1,200 × g for two hours, at 25° C.

To produce the single cycle NL4-3, the pNL4-3-ΔEnv GFP NL43dE vector was transformed into Stbl-3 cells (Invitrogen) to amplify, and co-transfected into 293T cells with an X4 Env plasmid to produce single round replication pseudovirus. After a three day transfection, cellular debris were removed by centrifugation and filtration through Steriflip filters (Millipore). Virus was collected by ultracentrifugation at 1,200 × g for two hours, at 25° C.

Reactive CTL epitopes were defined by IFN-γ ELISPOT. As previously described [28], whole blood was taken from each patient and PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll gradient centrifugation. PBMCs were aliquoted into each well of 96 well MultiScreen (Millipore) plates with conjugated IFN-γ antibody. Cells were activated with overlapping peptides spanning the entire amino acid sequence of B clade consensus gag and nef. Alternatively, cells were activated with peptides representing conserved epitopes in HLA-B*57. PBMCs were cultured overnight, and subsequently analyzed. Quantification of spot forming units was performed independently and in a blinded fashion.

Nucleotide sequences accession numbers

Full genome sequences from each patient have been submitted to GenBank XXX and have been assigned accession numbers JN397362 to JN397365.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI080328 (J.N.B.) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.F.S.).

Footnotes

Author Contribution

RWB performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. TGA, AA, MS and KAO performed experiments and edited the manuscript. SH, OFN, and JEG provided clinical information and clinical samples and edited the manuscript. TMW performed HLA typing and edited the manuscript, RFS analyzed data and edited the manuscript, JNB designed the study, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript.

Financial Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no competing financial conflicts of interest.

Accession codes: Sequence data have been deposited in XXX database under accession codes JN397362 to JN397365.

References

- 1.Ockulicz J, Lambotte O. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of elite controllers. Cur Op HIV ADS. 2011 May;6(3):163–168. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328344f35e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deacon, et al. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995 Nov 10;270(5238):988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kestler HW, 3rd, et al. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991 May 17;65(4):651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calugi G, Montella F, Favalli C, Benedetto A. Entire genome of a strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with a deletion of nef that was recovered 20 years after primary infection: large pool of proviruses with deletions of env. J Virol. 2006 Dec;80(23):11892–11896. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00932-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariani R, Kirchhoff F, Greenough TC, Sullivan JL, Desrosiers RC, Skowronski J. High frequency of defective nef alleles in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1996 Nov;70(11):7752–7764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7752-7764.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirchhoff F, Greenough TC, Brettler DB, Sullivan JL, Desrosiers RC. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jan 26;332(4):228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iversen AK, et al. Persistence of attenuated rev genes in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected asymptomatic individual. J Virol. 1995 Sep;69(9):5743–5753. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5743-5753.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y, Zhang L, Ho DD. Characterization of gag and pol sequences from long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Virology. 1998 Jan 5;240(1):36–49. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miura T, et al. Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite controllers: lack of gross genetic defects or common amino acid changes. J Virol. 2008 Sep;82(17):8422–8430. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00535-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander L, Aquino-DeJesus MJ, Chan M, Andiman WA. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication by a two-amino-acid insertion in HIV-1 Vif from a nonprogressing mother and child. J Virol. 2002 Oct;76(20):10533–10539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10533-10539.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander L, et al. Unusual polymorphisms in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 associated with nonprogressive infection. J Virol. 2000 May;74(9):4361–4376. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4361-4376.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blankson JN, et al. Isolation and characterization of replication-competent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from a subset of elite suppressors. J Virol. 2007 Mar;81(5):2508–2518. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02165-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamine A, et al. Replication-competent HIV strains infect HIV controllers despite undetectable viremia (ANRS EP36 study) AIDS. 2007 May 11;21(8):1043–1045. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280d5a7ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julg B, et al. Infrequent recovery of HIV from but robust exogenous infection of activated CD4(+) T cells in HIV elite controllers. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jul 15;51(2):233–238. doi: 10.1086/653677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell KA, Brennan TP, Bailey JR, Ray SC, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. Control of HIV-1 in elite suppressors despite ongoing replication and evolution in plasma virus. J Virol. 2010 Jul;84(14):7018–7028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00548-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salgado M, et al. Evolution of the HIV-1 nef gene in HLA-B*57 positive elite suppressors. Retrovirology. 2010 Nov 8;7:94. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mens H, et al. HIV-1 continues to replicate and evolve in patients with natural control of HIV infection. J Virol. 2010 Dec;84(24):12971–12981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00387-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migueles SA, et al. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Mar 14;97(6):2709–2714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050567397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sajadi MM, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics and natural history of HIV-1 natural viral suppressors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Apr 1;50(4):403–408. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181945f1e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Migueles SA, et al. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity. 2008 Dec 19;29(6):1009–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.010. Epub 2008 Dec 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereyra F, et al. Genetic and immunologic heterogeneity among persons who control HIV infection in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 15;197(4):563–571. doi: 10.1086/526786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han Y, et al. The role of protective HCP5 and HLA-C associated polymorphisms in the control of HIV-1 replication in a subset of elite suppressors. AIDS. 2008 Feb 19;22(4):541–544. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f470e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambotte O, et al. SEROCO-HEMOCO Study Group. HIV controllers: a homogeneous group of HIV-1-infected patients with spontaneous control of viral replication. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Oct 1;41(7):1053–1056. doi: 10.1086/433188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emu B, et al. HLA class I-restricted T-cell responses may contribute to the control of human immunodeficiency virus infection, but such responses are not always necessary for long-term virus control. J Virol. 2008 Jun;82(11):5398–5407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02176-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Migueles SA, et al. HIV-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation is coupled to perforin expression and is maintained in nonprogressors. Nat Immunol. 2002 Nov;3(11):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/ni845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sáez-Cirión A, et al. Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida EP36 HIV Controllers Study Group. HIV controllers exhibit potent CD8 T cell capacity to suppress HIV infection ex vivo and peculiar cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Apr 17;104(16):6776–6781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611244104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hersperger AR, et al. Perforin expression directly ex vivo by HIV-specific CD8 T-cells is a correlate of HIV elite control. PLoS Pathog. 2010 May 27;6(5):e1000917. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey JR, et al. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from a patient who developed AIDS to an elite suppressor. J Virol. 2008 Aug;82(15):7395–7410. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00800-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brockman MA, et al. Escape and compensation from early HLA-B57-mediated cytotoxic T-lymphocyte pressure on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag alter capsid interactions with cyclophilin A. J Virol. 2007 Nov;81(22):12608–12618. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01369-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez-Picado J, et al. Fitness cost of escape mutations in p24 Gag in association with control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2006 Apr;80(7):3617–3623. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3617-3623.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connell KA, Brennan TP, Bailey JR, Ray SC, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. Control of HIV-1 in elite suppressors despite ongoing replication and evolution in plasma virus. J Virol. 2010;84(14):7018–7028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00548-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Doherty U, Swiggard WJ, Malim MH. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J Virol. 2000 Nov;74(21):10074–10080. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10074-10080.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang H, et al. Novel single-cell-level phenotypic assay for residual drug susceptibility and reduced replication capacity of drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2004 Feb;78(4):1718–1729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1718-1729.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siliciano RF, Siliciano JD. Enhanced culture assay for detection and quantification of latently infection, resting CD4+ T-cells carrying replication-competent virus in HIV-1-infected individuals. Methods in Molecular Biology. 304 doi: 10.1385/1-59259-907-9:003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, et al. The role of a mutant CCR5 allele in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1996 Nov;2(11):1240–1243. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fellay J, et al. A whole-genome association study of major determinants for host control of HIV-1. Science. 2007 Aug 17;317(5840):944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1143767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin MP, et al. Epistatic interaction between KIR3DS1 and HLA-B delays the progression to AIDS. Nat Genet. 2002 Aug;31(4):429–434. doi: 10.1038/ng934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Migueles SA, et al. The differential ability of HLA B*5701+ long-term nonprogressors and progressors to restrict human immunodeficiency virus replication is not caused by loss of recognition of autologous viral gag sequences. J Virol. 2003 Jun;77(12):6889–9688. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6889-6898.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leslie AJ, et al. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat Med. 2004 Mar;10(3):282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crawford H, et al. Evolution of HLA-B*5703 HIV-1 escape mutations in HLA-B*5703-positive individuals and their transmission recipients. J Exp Med. 2009 Apr 13;206(4):909–921. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneidewind A, et al. Maternal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus escape mutations subverts HLA-B57 immunodominance but facilitates viral control in the haploidentical infant. J Virol. 2009 Sep;83(17):8616–8627. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00730-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferre AL, et al. HIV controllers with HLA-DRB1*13 and HLA-DQB1*06 alleles have strong, polyfunctional mucosal CD4+ T-cell responses. J Virol. 2010 Nov;84(21):11020–11029. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00980-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harari A, Petitpierre S, Vallelian F, Pantaleo G. Skewed representation of functionally distinct populations of virus-specific CD4 T cells in HIV-1-infected subjects with progressive disease: changes after antiretroviral therapy. Blood. 2004 Feb 1;103(3):966–972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereyra F, et al. Genetic and immunologic heterogeneity among persons who control HIV infection in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008 Feb 15;197(4):563–571. doi: 10.1086/526786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Younes SA, et al. HIV-1 viremia prevents the establishment of interleukin 2-producing HIV-specific memory CD4+ T cells endowed with proliferative capacity. J Exp Med. 2003 Dec 15;198(12):1909–1922. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tilton JC, et al. Changes in paracrine interleukin-2 requirement, CCR7 expression, frequency, and cytokine secretion of human immunodeficiency virus-specific CD4+ T cells are a consequence of antigen load. J Virol. 2007 Mar;81(6):2713–2725. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01830-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Betts MR, et al. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2006 Jun 15;107(12):4781–4789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lichterfeld M, et al. HIV-1-specific cytotoxicity is preferentially mediated by a subset of CD8(+) T cells producing both interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Blood. 2004 Jul 15;104(2):487–494. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodés B, et al. Differences in disease progression in a cohort of long-term non-progressors after more than 16 years of HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2004 May 21;18(8):1109–1116. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miura T, et al. Genetic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in elite controllers: lack of gross genetic defects or common amino acid changes. J Virol. 2008 Sep;82(17):8422–8430. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00535-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miura T, et al. Impaired replication capacity of acute/early viruses in persons who become HIV controllers. J Virol. 2010 Aug;84(15):7581–7591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00286-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brumme ZL, et al. Reduced replication capacity of NL4-3 recombinant viruses encoding reverse transcriptase-integrase sequences from HIV-1 elite controllers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Feb;56(2):100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fe9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miura T, et al. HLA-B57/B*5801 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite controllers select for rare gag variants associated with reduced viral replication capacity and strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte recognition. J Virol. 2009 Mar;83(6):2743–2755. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02265-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lassen KG, et al. Elite suppressor-derived HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins exhibit reduced entry efficiency and kinetics. PLoS Pathog. 2009 Apr;5(4):e1000377. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bailey JR, Williams TM, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. Maintenance of viral suppression in HIV-1-infected HLA-B*57+ elite suppressors despite CTL escape mutations. J Exp Med. 2006 May 15;203(5):1357–1369. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gaillard S, et al. Sustained elite suppression of replication competent HIV-1 in a patient treated with rituximab based chemotherapy. J Clin Virol. 2011 Jul;51(3):195–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexander L, et al. Unusual polymorphisms in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 associated with nonprogressive infection. J Virol. 2000 May;74(9):4361–7436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4361-4376.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mudd PA, Watkins DI. Understanding animal models of elite control: windows on effective immune responses against immunodeficiency viruses. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011 May;6(3):197–201. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283453e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedrich TC, et al. Subdominant CD8+ T-cell responses are involved in durable control of AIDS virus replication. J Virol. 2007 Apr;81(7):3465–2476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pandrea I, et al. Functional cure of SIVagm infection in rhesus macaques results in complete recovery of CD4+ T cells and is reverted by CD8+ cell depletion. PLoS Pathog. 2011 Aug;7(8):e1002170. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.