Abstract

Recent studies indicate that the gap over outer hair cells (OHCs) between the reticular lamina (RL) and the tectorial membrane (TM) varies cyclically during low-frequency sounds. Variation in the RL-TM gap produces radial fluid flow in the gap that can drive inner hair cell (IHC) stereocilia. Analysis of RL-TM gap changes reveals three IHC drives in addition to classic SHEAR. For upward basilar-membrane (BM) motion, IHC stereocilia are deflected in the excitatory direction by SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY, but in the inhibitory direction by TM-PUSH and CILIA-SLANT. Upward BM motion causes OHC somatic contraction which tilts the RL, compresses the RL-TM gap over IHCs and expands the RL-TM gap over OHCs, thereby producing an outward (away from the IHCs) radial fluid flow which is the OHC-MOTILITY drive. For upward BM motion, the force that moves the TM upward also compresses the RL-TM gap over OHCs causing inward radial flow past IHCs which is the TM-PUSH drive. Motions that produce large tilting of OHC stereocilia squeeze the supra-OHC RL-TM gap and caused inward radial flow past IHCs which is the CILIA-SLANT drive. Combinations of these drives explain: (1) the reversal at high sound levels of auditory nerve (AN) initial peak (ANIP) responses to clicks, and medial olivocochlear (MOC) inhibition of ANIP responses below, but not above, the ANIP reversal, (2) dips and phase reversals in AN responses to tones in cats and chinchillas, (3) hypersensitivity and phase reversals in tuning-curve tails after OHC ablation, and (4) MOC inhibition of tail-frequency AN responses. The OHC-MOTILITY drive provides another mechanism, in addition to BM motion amplification, that uses active processes to enhance the output of the cochlea. The ability of these IHC drives to explain previously anomalous data provides strong, although indirect, evidence that these drives are significant and presents a new view of how the cochlea works at frequencies below 3 kHz.

Keywords: cochlear mechanics, cochlear micromechanics, cochlear amplifier, BM motion amplifier, IHC drive amplifier

1. Introduction

A common view of cochlear micromechanics is that there is a simple proportional coupling of basilar membrane (BM) motion to IHC stereocilia with, perhaps, a small frequency dependence (Narayan et al., 1998). Outer hair cells (OHCs) were thought to amplify BM motion without changing this basic picture. In this view, BM motion causes the organ of Corti from the BM to the reticular lamina (RL) to move by tilting around the base of the inner pillar cells. OHC stereocilia were thought to connect the tectorial membrane (TM) to the RL in a way that keeps the TM a constant distance from the RL so that the TM exactly follows the transverse (perpendicular to the BM) movement of the RL. Since the organ of Corti from BM to the RL has a different pivot point than the TM, rotation produces radial shear between the RL and the TM (ter Kuile, 1900). This shear directly deflects OHC stereocilia leading to BM motion amplification, and indirectly, through viscous drag, deflects the freestanding inner hair cell (IHC) stereocilia leading to IHC transmitter release and excitation of auditory nerve (AN) fibers.

In contrast to this simple view, experiments in excised cochleae show more complicated motions. In response to sound, the organ of Corti rotates about the inner pillar cells but also deforms and Hensen cells vibrate with a different pattern than OHCs (Fridberger et al. 2002, 2006a). When motion is produced by applied current, OHC contractions pull the RL and the BM toward each other, which squeezes the fluid in the organ of Corti, bulges the organ of Corti out laterally and produces longitudinal fluid flow along the tunnel of Corti (Karavitaki and Mountain 2007a,b). At frequencies below 3 kHz, OHC contractions cause the RL to pivot about the head of the pillar cells (Scherer and Gummer, 2004; Nowotny and Gummer, 2006, 2011; Karavitaki and Mountain, 2007b). As the RL over the OHCs moves down, the OHC stereocilia pull the TM down and the rest of the TM follows in phase with the RL transverse motion over OHCs. Over the IHCs, the TM moves down as the tilting RL moves up (Nowotny and Gummer, 2006, 2011; Chiaradia et al. 2009). The antiphasic RL and TM motions over the IHCs changes the RL-TM gap and produces fluid flow that deflects IHC stereocilia (Nowotny and Gummer, 2006). These complex motions were observed in excised cochleae. Recent work in live, sensitive guinea pigs show that RL motion is larger than BM motion and grows nonlinearly in a different way than BM motion (Chen et al. 2011). All of these measurements indicate that normally, the drive to IHC stereocilia is related in a complex way to BM motion and is not simply a proportional coupling of BM motion with a small frequency dependence.

Evidence of how IHC stereocilia are mechanically excited can also be obtained from AN responses. Evidence from AN fibers is indirect but has the advantage that it can be obtained throughout the cochlea, whereas mechanical measurements can only be done in a few accessible regions. Furthermore, AN data can be obtained without opening the cochlea thereby preserving its normal operation. Many features of AN data cannot be explained by a simple transformation of BM motion to IHC stereocilia motion. Past attempts to decipher IHC drives from AN responses have provided some insights but left various phenomena unexplained (Guinan, 2009), e.g. for high-level clicks, the AN initial peak (ANIP) response is excited by condensation clicks, opposite from what would be expected (Lin and Guinan, 2000). Furthermore, intracellular responses from IHCs show similar unexplained phenomena, i.e. at high levels IHCs were depolarized for BM velocity to scala tympani (ST) (Cheatham and Dallos, 1998).

A key idea, suggested by several mechanical measurements, is that the distance between the RL and the TM is not fixed. Two kinds of experiments point to this. First, as already noted, many measurements show that the RL tilts about the top of the pillar cells when OHCs change length and this squeezes the RL-TM space over IHCs (Scherer and Gummer, 2004; Nowotny and Gummer, 2006, 2011; Karavitaki and Mountain, 2007b). Second, measurements at the top and bottom of OHC stereocilia show differential motion, which implies that the OHC stereocilia stretch/compress during a sound cycle (Hakizimana et al. 2011a,b). Although much more needs to be learned about stereocilia elasticity, these measurements indicate that the OHC stereocilia do not necessarily hold the TM a fixed distance from the RL over the OHCs. Thus, these two sets of measurements indicate that the RL-TM gap can change both over IHCs and over OHCs. The RL-TM gap is filled with fluid and any change of the gap requires fluid flow within the gap. Some of this fluid can be expected to flow past the IHC stereocilia and deflect the stereocilia thereby exciting the IHCs.

The purpose of this paper is to consider the implications of changes in the RL-TM gap on fluid flow within this gap and on the deflection of IHC stereocilia. First considered are how active and passive cochlear motions change the RL-TM gap, and what fluid flows and IHC deflections are expected from these gap changes. Next considered are AN data that have resisted explanation with traditional views of cochlear micromechanics. Explanations for these data are provided based on the hypothesized IHC drives produced by changes in the RL-TM gap. To aid in understanding the AN data, important aspects of the experimental methods are reviewed. A preliminary version of this paper has been presented (Guinan, 2011).

2. Hypothesized IHC drives

Changes in the RL-TM gap cause fluid flow in the gap, and this section considers how such fluid flows deflect IHC stereocilia. Two relevant questions are: (1) Will the fluid flow be in the radial direction or in the longitudinal direction? and (2) How large are the fluid flows and resulting IHC stereocilia deflections? Neither question can be answered definitively at the present time. Based on cochlear dimensions, it is argued in the Discussion that a substantial part of the fluid flow is in the radial direction across IHCs. In the Results, AN data are presented that are anomalous with the classic view that the only drive to IHC stereocilia is RL-TM SHEAR, but fit well with the view that these fluid flows significantly drive IHC stereocilia. With these in mind, we proceed on the assumption that changes in the RL-TM gap cause substantial fluid flows in the radial direction that deflect IHC stereocilia.

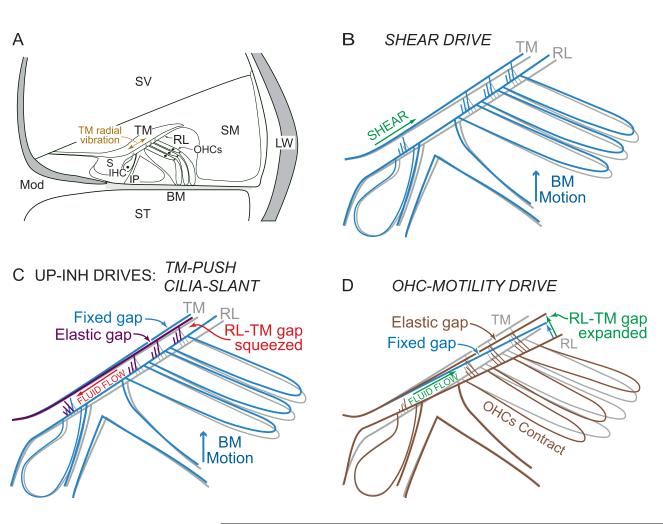

2.1 Shear and TM radial motion

Although this paper postulates that IHC stereocilia are driven, in part, by fluid flow from RL-TM gap changes, the classic RL-TM SHEAR drive is still expected to be present (Fig. 1A, B). In the classic view, the organ of Corti and the RL pivot about the foot of the inner pillars while the TM pivots about its insertion in the spiral lamina. When the BM moves up, the pivoting causes the motion of the RL to be partly in the radial direction toward the modiolus. In contrast, as the TM moves up, it has very little radial movement. The result is RL-TM SHEAR which deflects OHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction (Fig. 1B). Since the IHC stereocilia are not imbedded in the TM, the coupling between the TM and IHC stereocilia is through viscous drag by the fluid. In an analysis that viewed IHC stereocilia as rigid structures hinged on a vibrating RL with a vibrating TM above, at low frequencies IHC stereocilia deflection was sensitive to the velocity of the TM relative to the RL (Freeman and Weiss, 1990a,b). However, at high frequencies the IHC stereocilia followed RL-TM SHEAR displacement, i.e. IHC stereocilia moved as if they were attached to the TM but with a lower motion amplitude. Thus, the traditional view of the SHEAR drive to IHCs considers there to be velocity coupling at low frequencies and displacement coupling at high frequencies.

Figure 1.

Outlines of the organ of Corti showing the four IHC drives. A: A cross section through the apical cochlea. B-D: Expanded views of the central part of organ of Corti showing the at-rest structures as gray. B (SHEAR): Upward movement (blue) of the basilar membrane (BM) toward scala vestibuli (SV) causes shear between the reticular lamina (RL) and the tectorial membrane (TM). Since the organ of Corti rotates about the foot of the inner pillar cells (IP), the RL movement has a significant radial component toward the modiolus (Mod). In contrast, the TM rotates about its insertion and shows little radial movement. Although the IHC-stereocilia radial shear motion is toward the modiolus, the rotational component is in the excitatory direction (Green arrow). C (UP-INH drives): (1) TM-PUSH: Upward BM movement causes TM movement by forces transmitted through the OHC stereocilia which produce less TM movement (purple) than for a fixed gap (blue). The resulting squeezing of the RL-TM gap forces fluid past IHC stereocilia in the inhibitory direction. (2) CILIA-SLANT: The decrease in the RL-TM gap over OHCs is caused by tilting fixed-length OHC stereocilia (as in Figure 3b) thereby forcing fluid past IHC stereocilia in the inhibitory direction. D (OHC-MOTILITY): OHC contractions pull the TM down through forces on the OHC stereocilia that expand the RL-TM gap over OHCs (brown) compared to a fixed gap (blue). The OHC contractions also produce rotation of the RL about the head of the pillars that squeezes the RL-TM gap over IHCs. Both of these gap changes produce fluid flow that deflects IHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction. The rotations of contracted OHC cell bodies are patterned after results of Karavitaki and Mountain (2007b). IHC=inner hair cell, OHCs=outer hair cells, S=inner sulcus, ST=scala tympani, SM=scala media, LW=lateral wall.

At low frequencies TM behavior is dominated by its viscoelastic properties, but at high frequencies TM mass is important. Many cochlear models have considered the TM to be a mass attached by springs at the modiolus and at the OHC stereocilia. Some models posit that the TM vibrates in the radial direction with a resonance at a frequency below the local best frequency (Allen, 1980; Zwislocki, 1980; also see Gummer et al., 1996). Such a resonance would mean that at high frequencies the motion of the TM over the IHCs can be dramatically different (indeed, opposite in phase) compared to that predicted by the simple RL-TM SHEAR model that assumes that BM, RL and TM move in phase. Recent measurements show that the TM can sustain high-frequency radial vibrations that travel longitudinally in a TM traveling wave (Ghaffari et al., 2007). These experiments did not show evidence of a TM resonance. Measurements in mutant mice indicate that the longitudinal coupling produced by TM traveling waves is important in shaping the resonance of the BM (Russell et al., 2007; Ghaffari et al., 2010). Both the TM models and these TM measurements point out the importance of the phase relationship between radial TM motion and RL motion at frequencies near the cochlear best frequency (BF). Unfortunately, there are no data from sensitive preparations that detail this relationship. Because of this, it is not now possible to specify the SHEAR drive at the OHCs and its effect on IHCs for frequencies near the BF. However, for frequencies far below BF, little TM radial motion is expected, and little TM radial motion has been found in excised preparations (Chan and Hudspeth, 2005; Karavitaki and Mountain, 2007b). Thus, at low frequencies the RL-TM SHEAR drive appears be what is expected for in-phase movements of the structures.

Responses to clicks, particularly the initial part of the response to clicks, are examined in the Results, so RL-TM SHEAR for clicks must be understood. At the beginning of a click response, before any resonant motion has had time to build up, both the mass of the TM and its pivot point indicate that that the TM moves little in the radial direction compared to its movement in the transverse direction. In contrast, as indicated above, the RL pivots with the organ of Corti and has a significant radial component to its motion. The result is that for the first peak of the click response, the SHEAR drive is basically that expected for classic RL-TM SHEAR without an additional component due to resonant TM motion.

2.2 UP-INH drives: The TM-PUSH drive

Considered next are two ways in which upward BM movement can cause a decrease in the RL-TM gap over OHCs and produce deflections of IHC stereocilia in the inhibitory direction. The two mechanisms, termed “TM-PUSH” and “CILIA SLANT,” are quite different. Nonetheless, because their action is to deflect IHC stereocilia in the inhibitory direction for upward BM movement, collectively they will be called “UP-INH” drives.

2.2.1 TM-PUSH deflects IHC stereocilia in the inhibitory direction for upward BM motion

As the BM and organ of Corti move up (toward scala vestibuli (SV)), they cause the TM to move up by forces that, at low frequencies, are mainly coupled through the tallest row of OHC stereocilia and through the fluid in the RL-TM gap. At high frequencies, friction and fluid mass may prevent fluid flow in the RL-TM gap and serve to keep the RL-TM gap constant (Chadwick et al., 1996). However, at low frequencies the effects of friction and fluid mass are small so that the forces that move the TM are mostly delivered by the OHC stereocilia and elasticity in the coupling causes the TM to move less than the RL (detailed below). The resulting changes in the RL-TM gap cause fluid flow in the gap. The fluid in this reduced gap must flow somewhere, and while some may flow longitudinally or radially outward toward scala media, it is hypothesized here (see section 5.5) that a substantial part of the fluid flows radially into the inner sulcus (Fig. 1C). This flow will deflect IHC stereocilia in the inhibitory direction, which is opposite the direction of the classic SHEAR drive (Fig. 1, B vs. C). This IHC drive is termed the “TM-PUSH” drive because it is primarily due to the change in the RL-TM gap from the forces that move the TM. This name should not be taken to mean that this drive is only present in the upward “push” direction; it also acts in the TM “pull” direction and then deflects IHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction. The TM-PUSH drive is a fluid drive that moves IHC stereocilia through viscous drag and can be expected to have velocity coupling at low frequencies and complex dynamics (e.g. see Chiaradia et al. 2009). Note that the TM-PUSH drive does not require active processes. In a passive cochlea, upward BM motion, through the TM-PUSH drive, causes fluid flow past IHC stereocilia in the inhibitory direction.

At low frequencies or in the initial response to clicks, upward BM motion produces an excitatory IHC SHEAR drive, and an inhibitory TM-PUSH drive. Although the same movement produces both, the SHEAR drive depends mostly on the velocity or position of the structures. In contrast, the TM-PUSH drive depends on the force that moves the TM which is related to the acceleration rather than the velocity or position of the structures.

What is the justification for hypothesizing the TM-PUSH will produce less motion of the TM than the RL? Motion of the BM causes TM motion by forces that are coupled, in part, through the OHC stereocilia. Because of this, at low frequencies the OHC stereocilia and their attachments at the RL and TM are exposed to forces concentrated in a very small area, i.e. the cross sections of the tallest row of OHC stereocilia. With this in mind, three mechanisms by which the RL-TM gap may change are identified:

2.2.2 RL-TM gap changes by stereocilia length changes

Recent measurements of the motions at the base and tip of OHC stereocilia in excised guinea-pig cochleae showed that OHC stereocilia change length during organ of Corti motion (Hakizimana et al. 2011a,b). Changing the polarity of current passed through the preparation (current was used to mimic endocochlear potential) produced radically different stereocilia length changes. This paper did not provide estimates of the magnitude of stereocilia length changes in a living, sensitive cochlea. However, it can be concluded from this paper that the distance between the RL and the TM is not held fixed by the OHC stereocilia and that forces transmitted through the OHC stereocilia can lead to changes in the RL-TM gap over OHCs.

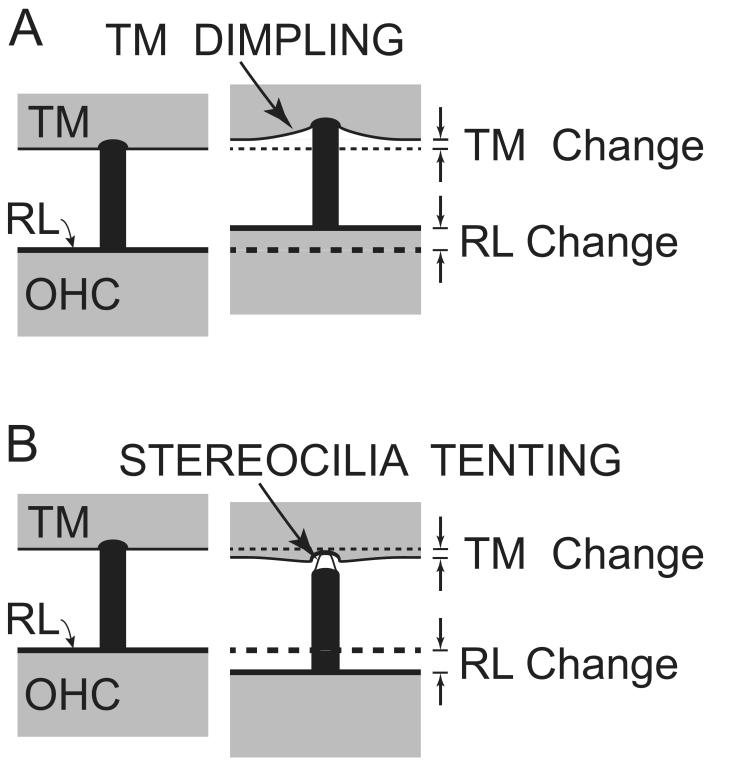

2.2.3 RL-TM gap changes by dimpling of the TM

As the organ of Corti moves up (toward SV), the OHC stereocilia push upward on the TM which will dimple a local area of the TM (Fig. 2A). Because of this dimple, the overall TM-RL distance is reduced from its rest value. The indentation of an elastic half-space with a probe produces a nonlinear dimpling with the greatest ratio of dimpling to probe motion at low amplitudes (e.g. see Shoelson et al., 2004). Since the tops of OHC stereocilia are attached to the TM, similar changes are expected to occur for upward and downward motion so that for small enough displacements the dimpling is linear.

Figure 2.

Two ways (in addition to elasticity in the stereocilia themselves) in which movement of the reticular lamina (RL) over outer hair cells (OHCs) may give rise to less movement of the tectorial membrane (TM). A: TM dimpling, B: Stereocilia Tenting. Left: RL and TM in the rest condition. Right: Hypothesized TM position changes from an upward RL change (A) or a downward RL change (B).

2.2.4 RL-TM gap changes by membrane tenting

Although the actin filaments of the OHC stereocilia core are very stiff and may stretch and compress very little, the stereocilia core may not be connected rigidly to the stereocilia plasma membrane or to the TM. Membrane stretching at the tip of stereocilia is suggested by EM pictures that appear to show tenting of a membranous structure at the top of stereocilia (see Kim et al. 2011). The tenting seen in EM pictures may be a fixation artifact. However, even if the tenting seen in EM is an artifact, it suggests that the stereocilia membrane is not rigidly attached to the stereocilia core. One interpretation of the results of Hakizimana et al. (2011a,b) is that the measurements near the ends of the stereocilia were made from dye molecules attached to the stereocilia plasma membrane, and that this membrane moves relative to the actin core (see the comments at the end of Hakizimana et al. 2011b). We will refer to sliding of the stereocilia membrane relative to the stereocilia core as “membrane tenting”, while noting that this sliding may not correspond to the tenting seen in EM pictures. Such membrane tenting would allow the RL to move down without a commensurate downward movement of the TM (Fig. 2B). Membrane tenting may reduce the coupling to the TM of downward stereocilia movement and have little, or no, effect for upward stereocilia movement. This would impart a rectifying, nonlinearity on the RL-TM coupling and the resulting IHC drive. So far, stereocilia length changes, TM dimpling and stereocilia tenting have been considered as being due to separate elastic properties of these structures, but these structures are connected and these factors are likely to be intertwined.

2.2.5 Measurements of RL-TM gap changes

Changes in the RL-TM gap over OHCs have been measured in excised guinea pig cochleae with motion produced by electrically-excited OHC motility (Nowotny and Gummer, 2006, 2011). These measurements were made over each of the three OHC rows and in the apex, middle and base of the cochlea and were presented as averages with error bars from data from many guinea pigs. Most of the averages showed TM motion was slightly smaller than the RL motion, but the error bars were large so the differences were not statistically significant. These results and those of Hakizimana et al. (2011a, b) are both consistent with the hypothesis that the RL-TM distance is not fixed by the OHC stereocilia attachments. Experiments are needed to provide accurate measurements of stereocilia length changes, or more importantly, changes in the RL-TM gap over OHCs in live sensitive cochleae.

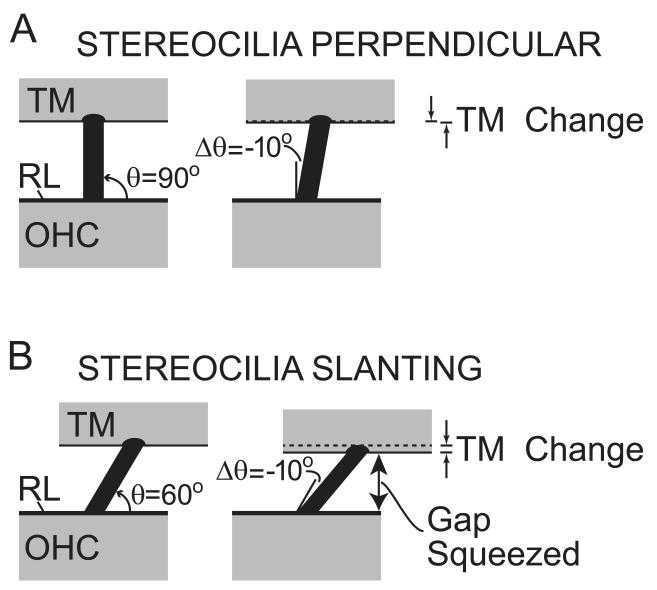

2.3 UP-INH drives: The stereocilia-slant (CILIA-SLANT) drive

If the OHC stereocilia are not perpendicular to the TM, then classic RL-TM shear that changes the angle of the OHC stereocilia will also change the RL-TM gap (Fig. 3). For instance, if the angle between the stereocilia and the RL is θ, and the stereocilia angle changes by Δθ, then, for small Δθ, the change in the gap is: Δθ times cosine(θ) times stereocilia length. Cosine(θ) is zero for θ=90°, so if the stereocilia are perpendicular to the RL and TM, then small deflections produce negligible gap changes. However, if θ is not 90°, either because there is a static stereocilia slant, or because the stereocilia deflection has become large, then the Δθ can cause a significant gap change. For instance, if θ =60°, then cosine(θ) is 0.5 and RL-TM shear at the OHC stereocilia will produce a change in the RL-TM gap that would produce fluid flow that deflects IHCs (Fig. 3B). For upward BM motion, the RL-TM gap over OHCs is squeezed (as in Fig. 1C) which results in fluid flow in the gap and IHC stereocilia deflection in the inhibitory direction. Thus, if θ is < 90°, the result will be an UP-INH drive which is termed the “stereocilia-slant” or “CILIA-SLANT” drive. If OHC stereocilia were slanted in the opposite direction at rest (i.e. θ > 90°) then the CILIA-SLANT drive would be in the opposite direction. However, arguments will be presented in section 4.6 that indicate that the CILIA-SLANT drive is an UP-INH drive. The geometrical arrangement shown in Figure 3 appears to imply that if sound level is high enough, the CILIA-SLANT drive must become significant, however, adaptive processes in the stereocilia mechano-electric transducer could significantly affect this drive, particularly at low sound frequencies. More direct experimental data are needed to determine the significance of the CILIA-SLANT drive and determine the rest angle of the OHC stereocilia.

Figure 3.

Stereocilia deflections produce a change in the RL-TM gap if the stereocilia are not perpendicular to the RL and TM. Left: RL and TM positions at rest. Right: RL and TM positions for a 10° decrease in stereocilia angle. θ is the angle between the stereocilia and the RL at rest and Δθ is the change in angle from the rest position.

Unfortunately, the normal angle, θ, between the stereocilia and the RL is not known and cannot be determined from fixed material. Since stereocilia adaptive processes and motility may influence stereocilia slant (Jacob et al., 2011a), it may be necessary to have a normal endocochlear potential to achieve a normal OHC stereocilia slant. However, measurement of θ in any unfixed tissue would be better than the present lack of knowledge.

TM-PUSH and CILIA-SLANT drives, although both UP-INH drives, arise from very different mechanisms and have different properties. The CILIA-SLANT drive is due to geometrical factors and depends on the OHC stereocilia slant and the change in the stereocilia angle which is expected to be related to BM displacement. In contrast, the TM-PUSH drive is due to the material properties of the OHC stereocilia and their attachment at both the RL and the TM. Also, TM-PUSH is expected to be related to structural acceleration (i.e. the force that moves the TM) rather than structure displacements. Note that both are passive, i.e. they do not require active mechanisms.

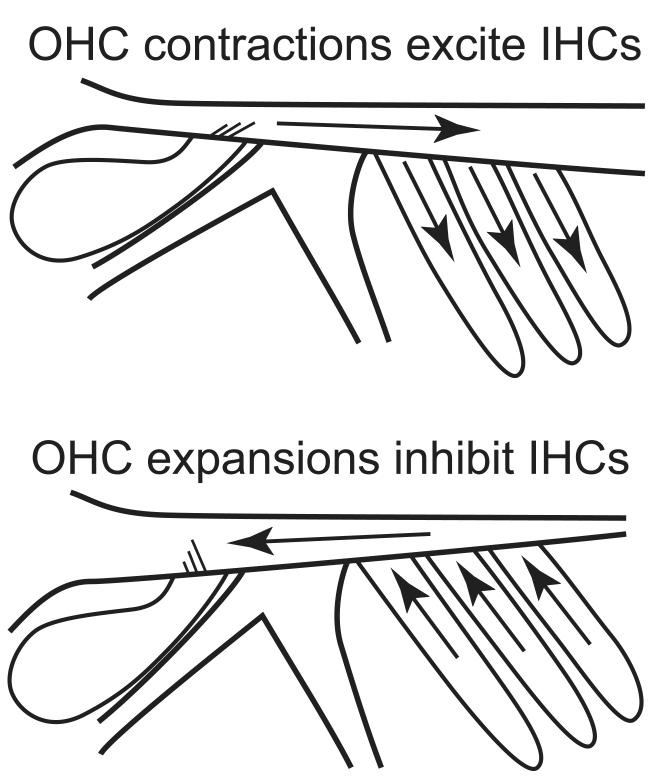

2.4 The OHC-MOTILITY drive

Normal sound-driven motion in an active cochlea is a complex mixture of motions that include the effects of OHC somatic motility. As a simplification, the effects of OHC somatic motility due to electrical stimulation are considered before OHC somatic motility in response to sound. One advantage of this choice is that there are published mechanical measurements for OHC electrical stimulation. Electrically-induced OHC contractions pull the RL toward the BM, and, through forces transmitted by the OHC stereocilia, produce transverse TM motion that is in phase all along the radial dimension of the TM (Nowotny and Gummer, 2006; 2011). The RL acts as a rigid bar pivoted about the head of the pillar cells, so that when the RL over the OHCs is pulled down, the RL over the IHCs moves up (Scherer and Gummer, 2004; Nowotny and Gummer, 2006, 2011; Karavitaki and Mountain, 2007b; Cooper and Szalai, 2011). The net effect is counterphasic motion of the RL and TM over the IHCs which periodically squeezes and expands the RL-TM gap. Nowotny and Gummer (2006) noted that changes in the RL-TM gap produce fluid movement that can deflect IHC stereocilia and then demonstrated this experimentally (Chiaradia et al., 2009). This group developed two model analyses to show how pulsating fluid flow within the RL-TM space might cause IHC stereocilia movement in the excitatory direction for electrically-induced OHC contractions, but these models assumed that OHC stereocilia produced rigid RL-TM connections (Gummer et al., 2006; Baumgart et al., 2009). However, as noted above, because of elasticity in the RL-TM connection, OHC contractions increase the gap over OHCs at the same time that the rotating RL decreases the gap over IHCs (Fig. 1D). This creates an easily seen mechanism for producing pulsating flow of fluid back and forth between these spaces. The IHC drive that results from this fluid flow is termed the “OHC-MOTILITY” drive. OHC contractions expand the space over OHCs and compress the space over IHCs, thereby producing a fluid flow toward the OHCs that deflects IHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction. Upward BM movement produces OHC contractions by RL-TM shear of the OHC stereocilia, at least at low frequencies. Thus, for upward BM movement, OHC motility produces an excitatory IHC drive.

Normally, OHC contractions originate from pressure differences across the cochlear partition from the traveling wave, and in these responses, all of the IHC drives are present and interact. In a sensitive cochlea, the RL-TM shear at the OHC stereocilia elicits OHC somatic motility, which at low frequencies acts in a negative feedback relationship to the shear, i.e. upward RL movement elicits OHC contractions that pull the RL down (Hubbard and Mountain, 1990; Lu et al., 2006). Thus, an active OHC-MOTILITY drive reduces the SHEAR and UP-INH drives. If the feedback loop gain is high, the OHC-MOTILITY drive may greatly reduce the SHEAR and UP-INH drives but it cannot reduce them to zero as long as the frequency is low and there is no resonant TM movement. Although the OHC-MOTILITY drive interacts with the other drives in complex ways, all of the drives remain present and retain the actions outlined in Figure 1. Thus, in an active cochlea there are two excitatory drives and two inhibitory drives and the net drive depends on the relative amplitudes of these various drives. Note also, that the SHEAR and UP-INH drives are passive and can continue to grow at high sound levels, while the OHC-MOTILITY drive is active, depends on cochlear energy sources and saturates at high sound levels.

2.5 Stereocilia motility

In mammalian OHCs, stereocilia motility is produced by two mechanisms, one that depends on calcium-activated closure of stereocilia mechano-electric transduction channels, and one that depends on prestin motility (Jia and He, 2005; Kennedy et al., 2006). Experiments using mice with knocked-out or genetically-modified prestin have established that prestin provides the main motor force that drives mammalian BM motion amplification (Liberman et al., 2002; Cheatham et al., 2004; Dallos et al., 2008). It is generally presumed that most of the force for BM motion amplification comes from OHC somatic motility. The role of calcium-activated stereocilia motility, if any, is unknown. OHC stereocilia motility, either prestin-based or from calcium-activated mechano-electric transduction channels, may play a role in BM motion amplification. Whatever its role in BM motion amplification, OHC stereocilia motility may also play a role at low frequencies and in the initial part of the response to clicks.

OHC stereocilia motility produces deflections of the OHC stereocilia. Such deflections would not be expected to have a direct influence on the RL-TM gap. However, they would be expected to influence the RL-TM shear at the OHCs and affect the SHEAR drive to IHCs. By changing the OHC shear, OHC stereocilia motility would affect the magnitude of the OHC-MOTILITY drive. The largest effect of this would be at frequencies near the BF, frequencies that are not analyzed in detail here. The possible effects of OHC stereocilia motility are difficult to estimate. For the conditions considered here, OHC stereocilia motility can be considered as making the translation between BM motion and RL-TM sheer more complicated but it would not change the basic actions of the identified IHC drives.

Another possibility that needs to be considered is IHC stereocilia motility. IHC stereocilia motility might amplify IHC motion in much the same way that it provides amplification in vestibular organs and in non-mammalian hearing (Hudspeth et al., 2000). This possibility has not been adequately explored from direct measurements on IHC stereocilia. For the purposes of the present paper, any amplification of the IHC stereocilia response due to IHC stereocilia motility can be considered as part of the IHC nonlinearity that translates the mechanical drives to the IHC stereocilia into IHC receptor currents and the resulting excitation of AN fibers. Knowing more about IHC stereocilia motility and its properties would be helpful in understanding the signal transformation that takes place in IHCs.

In summary, for sounds an octave or more below BF and for the initial part of click responses, there are four main drives to IHCs: (1) the classic RL-TM SHEAR drive, which for upward BM movement deflects IHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction, (2 and 3) passive TM-PUSH and CILIA-SLANT drives, which for upward BM movement compresses the RL-TM gap over OHCs causing inhibitory IHC deflections, and (4) an OHC-MOTILITY drive, which for upward BM motion expands the gap over OHCs and produces RL rotation both of which deflect IHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction.

3. Methods Summary for AN Experiments

All of the data considered in detail here come from published AN studies. Full explanations of the methods can be obtained from the original publications. This section presents aspects of the methods that are particularly relevant to interpreting these data.

AN responses to clicks are an important source of the data considered, so it is important to understand how these click stimuli and other relevant methods differ from those commonly used. Clicks were generated by a reverse-driven condenser microphone, a transducer that produces acoustic waveforms that are the most punctuate in time of any reported. Nonetheless, the clicks were not perfect impulses and had some ringing (Fig. 1 of Lin and Guinan, 2000). High-level clicks produced room echoes that were found to elicit responses so the experimental chamber was sound-dampened (Lin and Guinan, 2000). Low-frequency “bias” tones were produced by a DT48 earphone. Stimulation of medial olivocochlear (MOC) efferents was done by a brainstem electrode (Stankovic and Guinan 1999; 2000; Guinan et al. 2005).

Auditory-nerve recordings provide indirect, imperfect measures of IHC mechanical drives, but several techniques can improve the AN representation of IHC drives. The IHC-AN synapse produces rectified responses (except near threshold), i.e. transmitter is primarily released during IHC depolarization. A display showing a full-cycle of the IHC drive (called a compound poststimulus-time histogram, or cPST) can be derived by plotting a spike histogram from rarefaction clicks upward and overlapping a histogram from condensation clicks plotted downward.

A second phenomenon that can distort AN responses is spike refractoriness, i.e. after a spike, the AN cannot fire again for about 1 ms and firing is reduced for a short time after that. Refractory effects can be greatly reduced by using recovered-probability histograms (Gray, 1967). A recovered-probability histogram shows the probability that spike occurred in each bin, conditioned on there having been no spike for a fixed time, T, before that bin (3 ms was used by Guinan et al. 2005). For high-level, low-rate clicks, almost every response has a spike at the time of the first PST peak, with the result that in the T ms period after the first PST peak, there are not enough responses without a spike in the preceding T ms for a recovered probability to be calculated. This difficulty was overcome by using high-rate clicks which caused adaptation at the IHC-AN synapse that lowered the first-spike probability (Lin and Guinan, 2000). A disadvantage of this procedure is that the degree of adaptation changed from one click level to the next so detailed quantitative comparisons can not be made across click levels.

4. AN Results and deduced IHC drives

4.1 Click data to be explained

The first set of data to be considered are AN responses to clicks, with and without various manipulations that affect OHCs and BM motion amplification. Clicks are a useful stimulus because they spread out in time the different stages of BM motion amplification. Two OHC manipulations are considered: (1) stimulation of MOC efferents and (2) two-tone suppression from low-frequency “bias tones”. MOC efferents reduce BM motion amplification by increasing the potassium conductance at the base of the OHCs which hyperpolarizes the OHCs and shunts OHC receptor currents, both of which reduce the OHC somatic motility from a given receptor current through the OHC stereocilia. Low-frequency bias tones reduce BM motion amplification at the level of OHC mechano-electric transduction channels by pushing the OHC stereocilia into low-slope regions of the mechano-electric transduction current-versus-angle relationship, i.e., they reduce the receptor current at the probe frequency. With these complementary manipulations, and the use of high-level clicks (note that clicks cause much less acoustic trauma than tones at the same level) there is a rich array of phenomena including many that cannot be explained by traditional concepts.

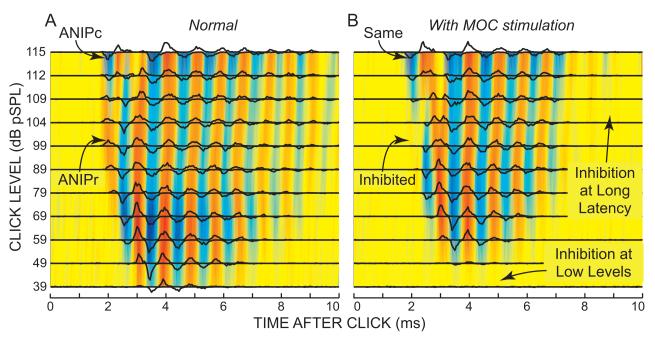

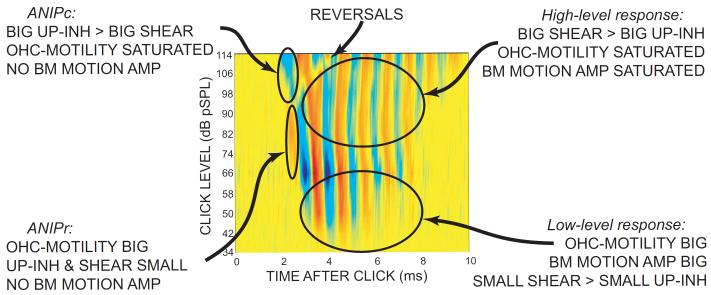

AN-fiber responses to clicks with the response features to be considered are shown in Figure 4A. This plot shows line drawings of cPST histograms from a variety of sound levels stacked vertically and superimposed on a color-coded, interpolated plot of the cPST data. The data show the classic pattern of response oscillations at the characteristic frequency (CF) of the fiber. A major exception to this pattern is seen at high levels in the early part of the response where the first peak is reversed, i.e. in the auditory nerve initial peak (ANIP) response, the polarity of the click that causes excitation reverses from low levels to high levels. This implies that the direction of the mechanical drive to the IHC stereocilia reverses at high levels and short latencies. To distinguish these areas, the ANIP response is subdivided into the response due to rarefaction clicks (ANIPr) and the response due to condensation clicks (ANIPc) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Click response patterns with (B) and without (A) medial olivocochlear (MOC) efferent stimulation. In each panel, lines show compound post-stimulus time (cPST) histograms from click level series, stacked vertically and superimposed on color-coded, interpolated plots of the cPST data. ANIP = auditory nerve initial peak. ANIPr = ANIP from rarefaction clicks. ANIPc = ANIP from condensation clicks. Red = response to rarefaction clicks; blue = response to condensation clicks; yellow = no response. Fiber characteristic frequency = 1168 Hz, spontaneous rate = 16 s/s. Note that the steps between click levels were smaller at high levels. Cat data obtained by Guinan et al. (2005).

The effects of MOC stimulation on the responses of this fiber are shown in Figure 4B. MOC stimulation turns down the gain of the BM motion amplifier, and as expected, the responses to low level clicks were greatly reduced. Another expected change is an MOC-induced reduction in the duration of the ringing response; this is consistent with MOC stimulation widening tuning curves. An unexpected effect of MOC stimulation was the strong inhibition of the ANIPr response (Fig. 4B). ANIPr inhibition was consistently found in AN fibers with CFs <4 kHz even when it was the largest response peak (Guinan et al. 2005). In contrast, the ANIPc response showed no MOC inhibition (Fig. 4B). The inhibition of the ANIPr response was unexpected because the first peak of BM responses to clicks is passive, as judged from its linear growth, little-changed presence after death, and lack of MOC inhibition when measured in the cochlear base (Recio et al. 1998; Guinan and Cooper, 2008).

The second set of data to be considered is the effect of high-level, low-frequency, “bias” tones on click responses (Nam and Guinan, 2011). At click levels near threshold, click responses, like tone responses, are suppressed twice each bias tone cycle, presumably from the bias tone pushing the OHC stereocilia into low-slope regions of their mechano-electric transduction functions thereby lowering BM motion amplification. Similar twice-a-bias-tone-cycle suppression was seen in the long-latency part of the click responses. The ANIPr response was also found to be suppressed twice each bias-tone cycle, but with the major suppression at the opposite phase of that found for low-level click responses (Nam and Guinan, 2011). Finally, the ANIPc response was not suppressed twice each bias-tone cycle but was modulated approximately sinusoidally over the tone cycle (Guinan, 2009).

Both MOC and bias-tone effects agree in indicating that active processes in OHCs are involved in producing click responses when traditional BM motion amplification is involved, i.e. at low sound levels and long latencies. Also, both MOC and bias-tone effects agree in indicating that active processes in OHCs are involved in producing ANIPr responses, although the bias-tone effects suggest that there may be some difference between the OHC effects on ANIPr and on near-threshold click response. Finally, both MOC and bias-tone effects are consistent with the hypothesis that the ANIPc response does not depend on active processes in OHCs, and that ANIPc may be a passive response.

4.2 Hypotheses for the IHC drives that produce the click responses

This section attempts to explain the click-response data in terms of the IHC drive mechanisms of Figure 1. Because it appears to be the simplest response to explain, first considered is the ANIPc response in a cochlea where OHC active processes have been inhibited by MOC stimulation (Fig. 4B). The ANIPc response has a latency that is too long for it to be attributed to a direct effect of the fast pressure wave (Guinan, 2009). Since it is the earliest response, it appears to be a response to the first peak of the click traveling wave. Also, as noted above, the ANIPc response is not MOC inhibited or suppressed twice-a-cycle by bias tones so it appears to be a passive response. Two kinds of IHC drives have been identified as present in a passive cochlea: the SHEAR and UP-INH drives (Fig. 1). These drives act in opposite directions. ANIPc is a response to condensation clicks, and for the initial peak of condensation clicks (which pushes the BM down) only the UP-INH drives are excitatory. Arguments will be presented later that the TM-PUSH drive is the main source of ANIPc, but for now it is adequate to say that ANIPc is a response that is dominated by UP-INH drives. Presumably, the SHEAR drive is also present, but at high levels in this first peak, the direction of the response argues that the net effect of the UP-INH drives is larger than that of the sheer drive.

Next, consider ANIPr. It occurs at approximately the same time as ANIPc so it is also a response from the first peak of the click traveling wave. However, in contrast to ANIPc, ANIPr is inhibited by MOC efferents and suppressed by bias tones, so it is due to, or strongly influenced by, active processes in OHCs. Thus, in addition to the passive SHEAR and UP-INH drives, the active OHC-MOTILITY drive is also involved. Classic BM motion amplification, an active process, is unlikely to be involved because the first peak of the BM response to clicks is passive (Recio et al. 1998; Guinan and Cooper, 2008). The ANIPr response is produced by rarefaction clicks. From this, it appears that the addition of the excitatory1 OHC-MOTILITY drive adds enough to the excitatory SHEAR drive to overcome the inhibitory UP-INH drives and produce excitation in the first response peak. Why don’t these excitatory drives continue to dominate at high levels? Because, as sound level is increased, the active OHC-MOTILITY drive saturates while the passive drives continue to grow. Thus, for the ANIP responses in Figure 4, in the 104-112 dB pSPL range, the active OHC-MOTILITY drive saturates while the passive SHEAR and UP-INH drives continue to grow with the UP-INH drives dominating the response at the highest levels.

In some AN fibers at high sound levels, there were reversed regions after ANIPc on the 2nd and 3rd click-response peaks (e.g. Figs. 4 & 5; also Fig. 4 of Lin and Guinan, 2000). The sound level at which the peaks reversed increased with time after click onset, which means that the relative proportions of the drives changed with time. In particular, for upward BM motion, the excitatory SHEAR drive must have increased with time compared to the inhibitory UP-INH drives (presuming that active processes were saturated at these high levels). What causes this change with time? In responses to clicks, BM motion is small on the first cycle and builds up over the first few cycles (Recio et al. 1998; Guinan and Cooper, 2008), thus the excitatory SHEAR drive starts small and builds up. The inhibitory CILIA-SLANT drive also depends on structural displacements and starts small and builds up. In contrast, the inhibitory TM-PUSH drive is due to the pressure difference across the cochlear partition which supplies the force to move the BM and the TM. In response to clicks, measurements of the pressure in ST close to the BM showed a traveling wave component that grew only slightly from the first to the second peak and stayed the same or declined after that (Olson, 2001). Thus, over the first few peaks of the click response, the SHEAR and CILIA-SLANT drives both increase whereas the TM-PUSH drive changes relatively little. As a result, the ratio of the excitatory SHEAR drive to the inhibitory UP-INH drives increases with time after click onset, and this ratio change accounts for the observed increase with time in the level at which the phase reverses in the early peaks of AN click responses.

Figure 5.

Color-coded cPST histograms as in Fig. 4 from click responses showing reversals that occur at higher levels for later peaks. Labels indicate the relative dominance of the IHC drives and the state of the BM motion amplifier. In ANIPc, the UP-INH drive is largely TM-PUSH rather than CILIA-SLANT. Cat data obtained by Lin and Guinan (2000).

Below the reversals, the post-ANIP response continues the oscillatory pattern seen in ANIPr so, presumably, it is due to the same drives as ANIPr. Why is ANIPr inhibited (even when it is the largest response – Guinan et al., 2005) while later peaks are not? There are two ways that the ANIP response is different from later response peaks: (1) It has no BM motion amplification, and (2) It has the lowest SHEAR / (TM-PUSH + CILIA-SLANT) ratio. In the later peaks at low sound levels, the responses are enhanced both by BM motion amplification and by OHC-MOTILITY increasing the drive to IHC stereocilia. At higher levels, the active processes saturate but the oscillatory pattern continues because the excitatory SHEAR drive, which is big when BM motion is big, substitutes for the saturated excitatory OHC-MOTILITY drive. Thus, at the sound levels at which ANIPr is seen, SHEAR is low and OHC-MOTILITY is not saturated in the ANIPr response, but at these same sound levels in later peaks, BM motion is greater and SHEAR substitutes for a saturated OHC motility drive (Fig. 5).

4.3 Tone Response Phase Reversals

The drives that produce click responses also produce tone responses. One major difference is that the cycles of ringing in the click response are overlapped in tone responses. Thus, in tone responses the mix of drives that produce the ANIP responses are combined with the mix of drives that produce the post-ANIP responses.

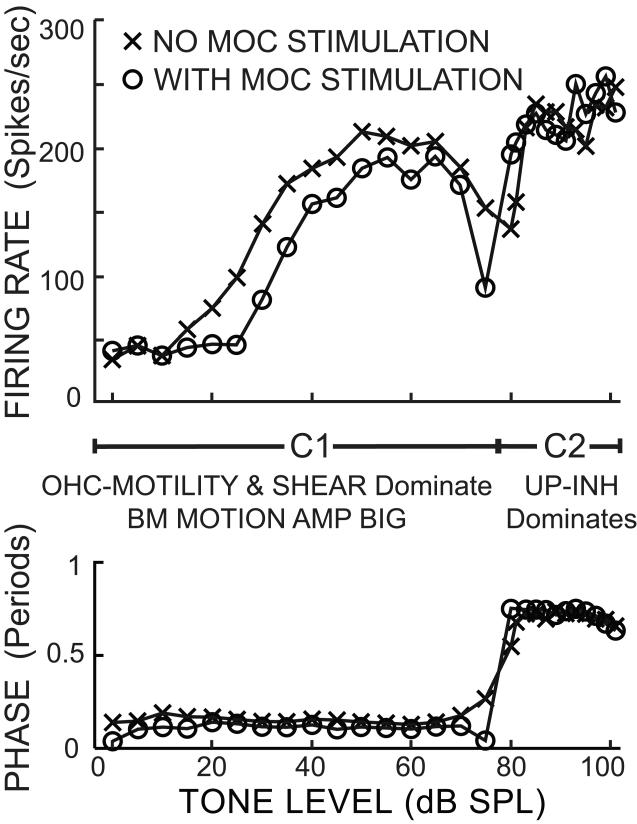

Most AN responses to tones near the best frequency (BF) are too difficult to explain at present because of inadequate knowledge of the TM vibration pattern near CF. However the responses to tones in the 1 kHz CF region in cats are so similar to the ANIP responses that they invite a similar analysis. Data from an illustrative single AN fiber are shown in Figure 6. This fiber shows an abrupt change in phase at ~80 dB SPL. An analogous phase reversal was seen in guinea-pig IHC receptor potentials: at low levels IHCs depolarized for BM velocity toward SV and at high levels IHCs depolarized for BM velocity toward ST (Cheatham and Dallos, 1998). There are also phase reversals in chinchilla AN responses that will be considered in section 4.6. In the cat AN data, responses below the reversal (called component 1 or C1) were inhibited by MOC stimulation and responses above the reversal (called component 2 or C2) showed no MOC inhibition (Gifford and Guinan, 1983). This pattern is similar to the ANIPr and ANIPc data and a similar interpretation fits, i.e. the SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY drives dominate the C1 response and the oppositely-directed UP-INH drives dominate the C2 response. The C1 response is MOC inhibited because MOC stimulation inhibits the OHC-MOTILITY drive and BM motion amplification both of which contribute to C1. Above the dip, the response reverses so, presumably, the UP-INH drives are dominant. Since the OHC-MOTILITY drive and BM motion amplification are still present in C2, their inhibition would be expected to increase the response. MOC stimulation does increase the response in the two points just above the dip but not in the points at the highest levels in Figure 6, or in most of the data showing MOC effects above a dip (Gifford and Guinan, 1983). Presumably this is because the rate above the dip is limited by saturations both in the active OHC processes and at a later stage (e.g. in the amount of transmitter released at the IHC-AN synapse) so that although at high levels IHC drive may be increased by MOC inhibition, there is not always a corresponding increase in AN firing rate.

Figure 6.

Rate and phase as a function of sound level for a single auditory-nerve fiber with and without MOC stimulation. The response below the phase reversal is termed component 1 (C1) and that above the phase reversal component 2 (C2). Below the reversal, OHC-MOTILITY and SHEAR drives dominate the IHC response and there is BM motion amplification. Stimulating MOC efferents reduces the response by reducing OHC-MOTILITY and BM motion amplification. Above the reversal, UP-INH drives dominate the response and these are not changed by MOC stimulation. Tone = 0.7 kHz, CF = 0.64 kHz. Cat data obtained by Gifford and Guinan (1983).

Which of the UP-INH drives is mainly responsible for the IHC drive in C2? For ANIPc, it was argued that the TM-PUSH drive is dominant because TM-PUSH depends on the pressure difference across the cochlear partition, which is highest on the first click peak, whereas the CILIA-SLANT drive depends on structural displacements which are small on the first click-response peak. However, for subsequent click peaks, the reversal point rapidly increases in level (Fig. 4 & 5) and for tone-response steady state, it may be that the TM-PUSH drive does not account for the reversal seen at 80 dB SPL in Figure 6. Liberman and coworkers (Liberman and Dodds, 1984; Liberman and Kiang, 1984) concluded that the drive that produces C2 is much more potent than the drive that produces C1, because all fibers showed high, saturation-level, rates in C2, even fibers with low spontaneous rates and very low rates in C1. This suggests that as sound level is raised the drive that produces C2 can become much larger than the other drives. At sound level increases at very high levels, all of the passive drives would be expected to continue to increase. However, the CILIA-SLANT drive, which depends on cos(θ) would be expected to increase its growth rate as sound level increases, and θ becomes high (see Fig. 3B). Thus, the data of Figure 6 are consistent with the main C2 drive being the CILIA-SLANT drive.

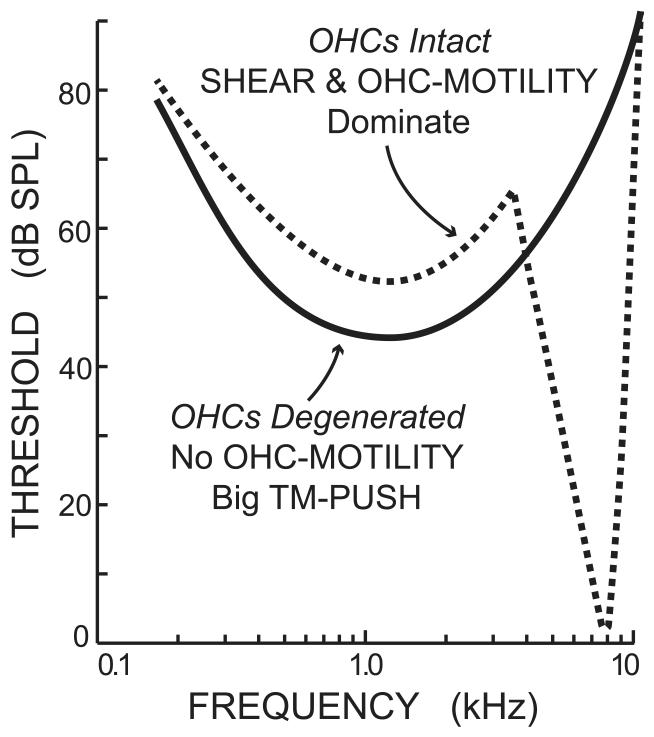

4.4 Tail hypersensitivity from OHC loss

Destroying OHCs by acoustic trauma or kanamycin treatment removes the sharp, sensitive tip of tuning curves and produces hypersensitivity in the low-frequency tuning curve “tail” (Fig. 7) (Dallos and Harris, 1978; Liberman and Dodds, 1984). Furthermore, hypersensitive tail responses have a phase opposite the phase of normal tail responses (Liberman and Kiang, 1984). The loss of the sensitive tip is consistent with the loss of BM motion amplification from OHCs. At tail frequencies, studies of BM motion show no amplification, so the tail responses have been thought to be due to passive processes (but see section 4.5). How is it that tail-frequency responses become hypersensitive when OHCs are removed? All of the passive IHC drives should be present in tuning-curve tails: SHEAR, TM-PUSH and CILIA-SLANT. For an upward BM motion, SHEAR is excitatory whereas TM-PUSH and CILIA-SLANT are inhibitory. Besides the loss of BM motion amplification, what is different when the OHCs are lost? One important thing is that the OHC stereocilia are lost. The TM is still there, but it no longer has the connection to the RL provided by the OHC stereocilia. Under these circumstances, movement of the RL is no longer transmitted to the TM by the OHC stereocilia and changes in the RL-TM gap over OHCs can be expected to be particularly large. With this in mind, a hypothesis that fits the data is that in the TC tail there is normally a combination of excitatory SHEAR drive (perhaps with excitatory OHC-MOTILITY drive – see section 4.5) and inhibitory TM-PUSH and CILIA-SLANT drives with the excitatory drives being larger. After degeneration of OHCs and their stereocilia, any OHC-MOTILITY drive disappears and the supra-OHC gap change becomes much larger so that a much-larger TM-PUSH drive dominates the low-frequency response. This hypothesis accounts for both the increased sensitivity of the tail response and its phase reversal.

Figure 7.

Stylized tuning curves illustrating the effect of total OHC loss created either by acoustic trauma or treatment with kanamycin. The “OHCs Intact” curve is an estimate of the tuning curve before the pathology, based on tuning curves from the position along the cochlea of the labeled “OHCs degenerated” fiber. With OHCs degenerated, the tuning-curve tail is hypersensitive and has a reversed phase because the lack of OHC stereocilia greatly increases TM-PUSH which is an UP-INH drive. Drawings based on Kiang et al. (1986).

In a model proposed by Neely (1993), removing OHC motility produced tuning curves without tips and with hypersensitive tails similar to the one in Figure 7. In the model, removing OHC motility made the tails more sensitive because OHC motility exerted a negative feedback that reduced RL motion, so that removing this feedback resulted in increased RL motion and more sensitive tails. However, in this model removing OHC motility did not produce a reversal of the phase of the tail response, so this model cannot fully account for the data of Liberman and co-workers (Liberman and Dodds, 1984; Liberman and Kiang, 1984). Nonetheless, the mechanism described in the Neely model may account for part of the increase in tail sensitivity observed when OHCs are lost.

4.5 Active processes in IHC drives at tail frequencies

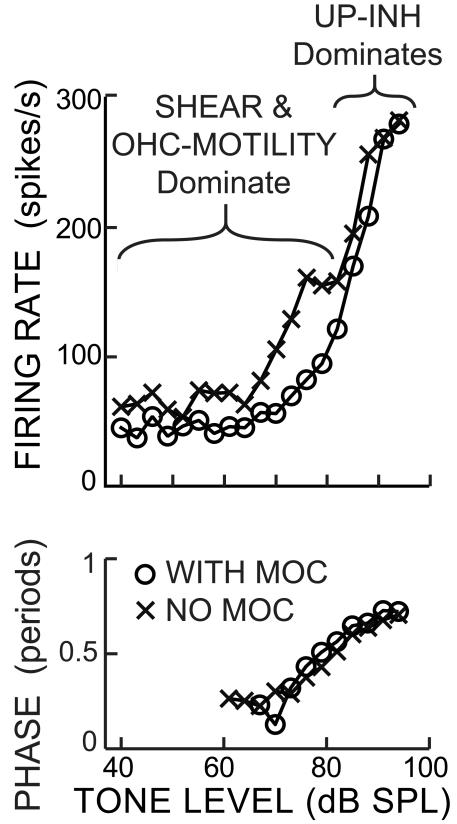

At frequencies an octave or more below the local BM best frequency, the growth of BM motion is linear, is affected little by MOC stimulation and is thought to be due to passive processes (Robles and Ruggero, 2001; Cooper and Guinan, 2006). Similarly, excitation of AN fibers at tail frequencies has typically been thought to be due to passive processes. However, Stankovic and Guinan (1999) found that activation of MOC efferents inhibited responses to tail-frequency tones in AN fibers with CFs >5 kHz. The inhibition was most prominent near threshold (which was typically 70 dB SPL or more), was often 10 dB or greater, and decreased as level increased so that by ~15 dB above threshold there was little or no MOC inhibition. The largest efferent inhibitions were at frequencies of 3 kHz (few measurements were above 3 kHz) and the inhibition decreased as frequency decreased. In some cases, there was a plateau in the response without efferent stimulation and the MOC inhibition was greatest in this plateau region (e.g. Fig. 8). In contrast with low-CF fibers, cat high-CF fibers never showed abrupt phase reversals such as those in Figure 6. In most fibers with CFs >5 kHz, as sound level increased, the phase slowly changed by 90-180° (e.g. Fig. 8) with larger phase changes for 2 kHz tones than for 1 kHz tones (Stankovic and Guinan, 2000). Efferent stimulation produced phase changes that were seldom more than 30° and these changes were typically in the same direction as the phase change produced by increasing the tone level (e.g. Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

MOC inhibition of an AN fiber response as a function of tone level at a tail frequency. Near threshold, SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY drives dominate the response and the OHC-MOTILITY drive is inhibited by MOC stimulation. At high levels, UP-INH drives dominate. The phase makes a slow transition as UP-INH slowly grows to dominate the response. Tone frequency = 2.0 kHz, fiber CF = 17.78 kHz, SR = 69.4 spikes/s. Cat data obtained by Stankovic and Guinan (1999, 2000).

Since the tail-frequency response is inhibited by MOC stimulation, it can be presumed to be due, at least in part, to active processes in OHCs. A hypothesis that fits the data is that near the tail threshold, there is an OHC-MOTILITY drive that saturates within 15 dB of the tail threshold and that this OHC-MOTILITY drive is inhibited by MOC efferents. Along with this OHC-MOTILITY drive there are the usual SHEAR and UP-INH drives, and these are responsible for the drive at levels far above threshold. For the fiber of Figure 8, it seems likely that the UP-INH drives are dominant at the highest levels because the phase at high levels is approximately opposite the low-level phase and the low-level response is enhanced by the OHC-MOTILITY drive which is an excitatory drive. This hypothesis supposes that as sound level increases, the UP-INH drives slowly become larger than the SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY drives and produce the slow phase change seen in Figure 8. As explained in the next section, it seems likely that the dominant UP-INH drive is the CILIA-SLANT drive. In contrast to the MOC inhibition of AN fiber responses, MOC stimulation does not reduce BM motion an octave or more below the best frequency (Cooper and Guinan, 2011). Presumably BM stiffness prevents the OHC-MOTILITY drive from having much effect on BM motion, but, because the RL’s rotational stiffness is much less, the OHC-MOTILITY drive is able to produce enough motion to change the RL-TM gap and drive the IHC stereocilia.

4.6 Multiple phase reversals in chinchilla auditory-nerve responses

In response to low-frequency (<1 kHz) tones, AN fibers in chinchillas show a complex phase-response pattern (Ruggero and Rich, 1987; Ruggero et al. 1996). Near threshold, AN fibers from the apical part of the cochlea (CFs < ~6 kHz) are excited at a phase of BM motion consistent with classic RL-TM SHEAR (considering that the free-standing IHC stereocilia respond to velocity at low frequencies and closer to displacement at high frequencies), but fibers from the basal part of the cochlea are excited at the opposite phase of BM motion. In apical fibers, as sound level is increased, near 90 dB SPL the response phase reverses so that at high levels AN fibers are excited at a phase opposite that expected from the SHEAR drive. In basal fibers as sound level is increased, there are two reversals of the response phase, so that at low and high sound levels fibers are excited at a phase opposite that expected from the SHEAR drive, and at intermediate levels they are excited at a phase close to that expected from the SHEAR drive.

Although the chinchilla pattern of reversals is complex, it can still be explained in terms of the four drives of Figure 1. At high sound levels the change in response phase from the classic response phase at a lower level to the opposite phase at higher levels is basically the same at all CFs (Ruggero et al 1996). Ruggero et al. (1996) puts this phase reversal as happening near 90 dB SPL. For tone frequencies 0.1-1 kHz in the chinchilla cochlear base, BM displacement is 1.9 nm at approximately 55 dB PL and BM growth is linear (Ruggero et al. 1986). Thus, the BM response to 90 dB SPL low-frequency tones is a displacement of approximately 0.34 μm. Dallos (2003) estimated that for every 1 μm of BM displacement, the OHC stereocilia angle changes by 40° in the gerbil cochlear base. Using this ratio for the chinchilla, the OHC stereocilia rotate 13° for a 90 dB SPL low-frequency tone. Although there is considerable uncertainty in this value, the result implies that at 90 dB SPL the OHC stereocilia angle change is large. With this in mind, a hypothesis that fits the data is that at 90 dB SPL the CILIA-SLANT drive becomes large enough to dominate the response. As the motion amplitude grows, θ deviates more from 90° (see Fig. 3), and because the CILIA-SLANT IHC drive depends on cosine(θ), the gap change and resultant CILIA-SLANT drive grow faster than linearly. This provides a reason why the CILIA-SLANT drive can become larger than the others so that it dominates the response at high levels and causes the phase reversal seen at 90 dB SPL.

The details of the AN single-fiber responses provide indirect evidence that normally the OHC stereocilia are not perpendicular to the RL and instead are tilted with the TM end of the stereocilia further from the modiolus than the RL end (as in Fig. 3B). If the stereocilia rest angle were 90°, then large excursions in both directions would cause squeezing of the RL-TM gap and a CILIA-SLANT inhibitory drive would occur twice each tone cycle (excitation would also occur twice each tone cycle as the stereocilia returned to the un-squeezed perpendicular position). AN data show that above the reversal the AN fiber response is primarily around the dominant phase with no evidence of a second excitatory region at the opposite phase (Ruggero et al 1996). This suggests that for downward BM motion which, through TL-TM shear, produces a positive Δθ in Figure 3, the net angle θ + Δθ has not swung significantly to greater than 90° (which would cause a gap reduction and thus two inhibitory and excitatory flows per cycle). Thus, the once-a-cycle excitatory AN response pattern at very high sound levels (Ruggero et al 1996) implies that θ is normally sufficiently less than 90° that Δθ does not cause two inhibitory/excitatory alternations per cycle2.

As the above analysis indicates, the CILIA-SLANT drive grows faster than linear for large amplitude signals, and may always become dominant at high-enough levels for low-frequency sounds. Data from chinchilla and guinea pig show AN excitation for BM motion toward scala tympani for low frequency, high-level sounds (Ruggero and Rich, 1987; Ruggero et al. 1996; Cheatham and Dallos, 1998) and cat data show similar reversals at low frequencies for low CFs (Fig. 6) (Gifford and Guinan, 1983; Liberman and Dodds, 1984; Liberman and Kiang, 1984) and somewhat slower reversals at high CFs (Fig. 8) (Stankovic and Guinan, 2000). Thus, when the sound level gets high enough, CILIA-SLANT may cause a reversal in the IHC low-frequency drive in all mammals.

A more difficult thing to explain than the high-level phase reversal is the second reversal seen at low levels in the chinchilla base (Ruggero and Rich, 1987; Ruggero et al. 1996) and perhaps also in guinea pigs (Sellick et al. 1982). The double reversal implies that UP-INH drives are dominant at low and high levels and at mid-levels the combined SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY drives are dominant. Why would the UP-INH drive be dominant at low and high levels but not between? One way would be if the CILIA-SLANT drive was dominant at high sound levels as suggested above, and the TM-PUSH drive was dominant at low sound levels. Reasons were given above why the CILIA-SLANT drive grows faster than linear so that it dominates at high sound levels. What is needed is a reason why the TM-PUSH drive might be dominant near threshold but not at higher levels. There is no compelling argument why this might be the case, but there are several possible reasons. TM dimpling (Fig. 2A) is a nonlinear phenomenon that would be expected to be greatest (relative to the force applied) at low levels and might allow a relatively large gap change at low levels. Another possibility is that the elasticity involved in membrane tenting is high for small stretches but decreases (i.e. becomes more stiff) when the membrane is elongated, like a rubber band. Another factor might be a slow growth at low levels of the OHC-MOTILITY drive – since to produce a reversal, the combined SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY drives must become larger than the UP-INH drives. Slow growth of the OHC-MOTILITY drive might happen because, at low frequencies in the cochlear base, adaptation in OHC mechano-electric channels is near complete at low levels but less complete at high levels (Eatock, 2000).

Whatever the source of the dominant UP-INH drive at threshold levels in the base, the base-to-apex reversal in the excitatory phase of threshold-level, low-frequency tones in chinchillas must be due to a change from dominance by an UP-INH drive in the base to dominance by SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY drives in the apex. Since a double phase reversal of responses to low-level, low-frequency tones has not been reported in the cat, it can be presumed that the base-to-apex anatomical differences involved are more prominent in the chinchilla than in the cat. Which of the various drives is the largest and therefore the dominant drive depends on anatomical factors that may vary across species and could easily vary from base to apex considering that many anatomical dimensions differ considerably from base to apex. Whether or not the details of the above explanations for the origin of AN phase reversals are correct, it seems likely that the drives of Figure 1 provide the building blocks that explain these phase reversals.

4.7 Reversals in AN Responses to Complex Signals

Wong et al (1998) measured cat AN-fiber responses to synthesized vowels as a function of sound level and found that the response phases of the vowel components reversed at high sound levels. Surprisingly, the responses to every frequency component of the vowel reversed at the sound level at which the largest frequency component reversed. This is not what would be expected if the response at each frequency component of the vowel was independent and reversed when the energy in that particular frequency component reached the reversal level for a single tone at that frequency. Wong et al (1998) used vowels that were a harmonic stimulus with phase-locked frequencies. A relatively simple interpretation of their data is that the highest-level component reversed when the stimulus level was high enough so that at most times during the overall stimulus cycle an UP-INH drive (presumably the CILIA-SLANT drive) was larger than the combined SHEAR and OHC-MOTILITY drives. When the UP-INH drives are dominant, downward movement of the BM produces excitation of IHC stereocilia and downward BM motion from any and all of the harmonic components will produce IHC excitation. Thus, once a single component moves the instantaneous combination of drives into a region where the UP-INH drives predominate, all frequency components will act in the opposite direction from their action at lower levels. So again previously mysterious data are well explained by the IHC drives of Figure 1.

5. Discussion

5.1 Overview

Experimental results, from both mechanical measurements and AN responses, have led to the conclusion that fluid flows due to changes in the RL-TM gap provide functionally significant drives to IHC stereocilia. The observation that OHC contractions produce pivoting of the RL about the top of the pillar cells has been reported by several investigators (Scherer and Gummer, 2004; Nowotny and Gummer, 2006, 2011; Karavitaki and Mountain, 2007b; Cooper and Szalai, 2011). The same OHC contractions that cause RL pivoting also produce TM motion with a phase that varies little with TM radial position (Nowotny and Gummer, 2006, 2011). The TM phase constancy plus the RL pivoting produce antiphasic motion over IHCs that periodically changes the RL-TM gap over the IHCs. Nowotny and Gummer pointed out that this would lead to fluid flow in the RL-TM space that would deflect IHC stereocilia, and this was confirmed experimentally in an excised cochlea by Chiaradia et al. (2009). However, with a constant RL-TM gap over OHCs, the most easily seen fluid flow from squeezing the RL-TM gap over IHCs is out into the inner sulcus which would produce an inhibitory drive to IHC stereocilia. By hypothesizing that downward pull by OHCs expands the RL-TM gap over OHCs, we provide an easily-seen mechanism by which this fluid flow would be excitatory to IHC stereocilia (Fig. 9). In short, the supra-OHCs gap change is in the opposite direction to the supra-IHCs gap change and is complementary. Together they create a pulsating fluid flow within the RL-TM gap similar to that proposed by Nowotny and Gummer (2006) but driven by gap changes over both the IHCs and OHCs instead of just gap changes over the IHCs.

Figure 9.

Cartoon showing how the OHC-MOTILITY drive enhances cochlear output by moving fluid back and forth radially within the RL-TM gap.

In addition to the above, changes in the RL-TM gap over OHCs are hypothesized to occur by two other mechanisms that produce passive UP-INH drives to IHC stereocilia. First, whenever there is transverse organ-of-Corti and TM motion, the force that moves the TM is transmitted through the OHC stereocilia and the fluid in the gap, and this RL-TM connection must have a degree of elasticity. Thus, changes in the RL-TM gap over OHCs can lead to fluid flow that drives IHC stereocilia (the TM-PUSH drive) even for passive movement of the BM and organ-of-Corti. The resulting TM-PUSH drive is in the opposite direction to the classic SHEAR drive (Fig. 1C). A second UP-INH drive (the CILIA-SLANT drive) is hypothesized to come from upward BM motion causing increased slanting of OHC stereocilia that squeezes the RL-TM gap and produces an inhibitory flow across IHC stereocilia (Fig. 3B). For low-frequency tones at high levels, this drive grows faster than linearly, so that when the sound level gets high enough the CILIA-SLANT drive dominates the response and produces AN response reversals. Thus, passive movement produces drives that are in the opposite direction from the SHEAR drive. The working hypothesis is that which drive dominates depends on the conditions and a change in dominance accounts for the reversals across sound levels seen in AN responses.

Although it seems clear that stereocilia and related structural elasticity can make motion of the TM be less than motion of the RL, an important question is whether this gap change is so small as to be insignificant or if it has perceptible effects. In experiments in excised cochleae with OHC motility produced by electrical current, Chiaradia et al. (2009) showed that OHC contractions produce fluid flow within the RL-TM gap that deflect IHC stereocilia in the excitatory direction. Because the RL-TM SHEAR from electrically-induced OHC contractions is in the opposite direction, the deflection of the IHC stereocilia must have come from fluid flow and not the RL-TM SHEAR drive. It cannot be discerned from the Chiaradia et al. (2009) experiment how much of the fluid flow within the gap comes from RL-TM gap changes over IHCs versus over OHCs, nonetheless, the results show that fluid flow from RL-TM gap changes can provide a significant drive to IHCs.

In the present paper, we show that the IHC drives from RL-TM gap changes over OHCs (the UP-INH drives), along with the OHC-MOTILITY and traditional SHEAR drives, can explain previously anomalous AN response phenomena, particularly the polarity of many previouslyanomalous high-level responses. Based on all of the above, we contend that the RL-TM gap changes over OHCs are physiologically significant.

Mountain and Cody (1999) also concluded that IHC responses were produced by multiple separate mechanical drives. They analyzed IHC receptor potentials and nearby extracellular potentials obtained from low-frequency stimulation of the guinea pig basal turn. BM motion amplification was not involved over the frequency range considered. To explain their empirical results, Mountain and Cody concluded that there was an OHC motility drive that provided direct coupling of OHC motility to IHC stereocilia without affecting BM motion, which is much like our OHC-MOTILIY drive. They concluded that there were two passive drives, which differs from our conclusion that there are three passive drives. However, Mountain and Cody may not have used high enough sound levels to see the high-level reversal, and their IHC drives were phenomenological descriptions without being constrained to a mechanical-vibrational counterpart, so their drives may not correspond exactly to any of our drives. Nonetheless, the work of Mountain and Cody (1999) provides a justification from a very different direction that IHC stereocilia are driven by multiple mechanical motions, with one dependent on OHC-generated forces and others that are passive.

It is interesting that passive cochlear motion produces drives that act in opposite directions and are sufficiently close in amplitude that they can sometimes cancel. Is this just a chance occurrence due to the details of complex mechanisms or could it have some advantage? It seems possible that the near cancellation of passive IHC drives allows the active drive to usually dominate at low levels and to provide a mechanism that limits the dynamic range of the drive to IHCs at levels where the active drive is saturated. Thus, the near cancellation of the passive drives may serve a function similar to the compressive nonlinearity of BM motion amplification in accommodating the wide range of sound levels into the narrow range of IHC responses.

5.2 Limitations and other considerations

There are several important limitations of our hypotheses. Friction and fluid mass in the RL-TM gap limits fluid flow at high frequencies, so fluid-flow drives will be reduced at high frequencies. Nowotny and Gummer (2006; 2011) saw RL rotation at frequencies up to at least ~3 kHz in all cochlear turns, and such rotation is only possible if there is fluid flow in the RL-TM gap. Guinan et al. (2005) found MOC inhibition of ANIPr responses up to 4-6 kHz, an inhibition that is interpreted here as due to efferent inhibition of the OHC-MOTILITY fluid drive. From these, a working hypothesis is that gap changes produce fluid drives to IHC stereocilia up to 3 kHz, at least.

Another important factor that needs further, more-detailed consideration is the phase characteristics of the IHC-stereocilia motion in response to the forces produced by the drives. All of the drives of Figure 1 act by fluid forces on the freestanding IHC stereocilia. The IHC stereocilia response (e.g., motion with fluid velocity or displacement) is a function of frequency. This has been ignored in our analysis because we think that the phases of the IHC responses to the four drives mostly change together so these phase changes do not affect the fundamental picture of which drives are in phase and which are not. This does not mean, however, that there are no phase changes. The response phases can be changed by up to 90° at more than one stage, so large phase changes (relative to BM motion) of the drives are possible. One area that needs more work is to determine the extent to which the TM-PUSH drive has a different phase than the other drives because it is due to structural acceleration rather than velocity.

5.3 Models of the drive to IHCs

There have been a variety micromechanical models that explored the factors involved in shaping the mechanical drive to IHCs. Modeling of the SHEAR drive indicates that the deflection of IHC stereocilia follows shear velocity at low frequencies and/or for large distances between the top of the IHC stereocilia and the TM, whereas IHC stereocilia deflection follows shear displacement for high frequencies and small stereocilia-top to TM distances (Freeman and Weiss, 1990a,b; Steele and Puria, 2005; Steele et al. 2009; Baumgart, et al. 2009). There is also a considerable range of intermediate frequencies and stereocilia-top to TM distances at which the behavior is intermediate.

These models only considered the SHEAR drive to IHCs, but the other drives will also be influenced by frequency and by the stereocilia-top to TM distance, although perhaps in a somewhat different way. At the lowest frequencies, the IHC deflection response to all of the drives is expected to be sensitive to the fluid velocity. At higher frequencies, the IHC response to the SHEAR drive becomes closer to a fluid displacement sensitivity, as noted above. Since the non-SHEAR drives are all from pure fluid flow, without a differential radial motion between the RL and the TM, their behavior, as a function of frequency, may not be the same as that of the SHEAR drive. At high frequencies, for all of these drives, the mass of the fluid will become important so that the IHC stereocilia may no longer move in phase with structural velocities but instead may move closer to structural displacement. Measurements and models are needed to show the phase relationships of IHC stereocilia motion to the fluid drives.

A few models explicitly considered the possibility that the RL-TM gap may change. The model of Chadwick et al. (1996) assumed an asymptotically large damping in the RL-TM space which resulted in their being no change in the RL-TM gap. This assumption would apply at high frequencies but not at low frequencies. Following this, Smith and Chadwick (2011) assumed that since the RL-TM gap stayed constant, the OHC stereocilia could stretch.

From a realistic, fluid elastic model, Steele and Puria (2005) and Steele et al. (2009) concluded that: (1) in the cochlear base the TM is very stiff so that as the BM moves down, the RL-TM gap at the inner sulcus opens and causes fluid flow past IHC stereocilia that accounts for the non-classical AN response phase observed in chinchillas by Ruggero and Rich (1987) and Ruggero et al. (1996), whereas (2) in the apex the TM is flexible so there is little or no sulcus-opening drive and the classic SHEAR drive dominates. As envisioned by Steele and Puria, this “sulcus-opening” drive has a role in the chinchilla basal-turn reverses but does not have a role in the apical reverses and would not, by itself, explain why there are two reversals in basal-turn chinchilla AN fibers. These authors note that, according to their model, by choosing different TM stiffnesses and different distances between the top of the IHC stereocilia and the TM, that IHC stereocilia response phase can be put in any of the 4 phase quadrants relative to BM motion. It is not clear whether the TM in the base is actually stiff enough to produce significant “sulcus-opening” and the resulting phase reversal of the IHC drive. The “sulcus-opening” flow described by Steele and Puria may constitute another UP-INH drive to the IHC stereocilia and might add significantly to the UP-INH drives of Figure 3c. It is possible that the SULCUS-OPENING drive may be the major source of the non-classical AN response phase in the chinchilla basal turn, instead of the CILIA-SLANT drive.

5.4 Peak splitting