Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a highly heterogeneous disease, and prior attempts to develop genomics-based classification for HCC have yielded highly divergent results, indicating difficulty to identify unified molecular anatomy. We performed a meta-analysis of gene expression profiles in datasets from 8 independent patient cohorts across the world. In addition, aiming to establish the real world applicability of a classification system, we profiled 118 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues from an additional patient cohort. A total of 603 patients were analyzed, representing the major etiologies of HCC (hepatitis B and C) collected from Western and Eastern countries. We observed 3 robust HCC subclasses (termed S1, S2, and S3), each correlated with clinical parameters such as tumor size, extent of cellular differentiation, and serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. An analysis of the components of the signatures indicated that S1 reflected aberrant activation of the WNT signaling pathway, S2 was characterized by proliferation as well as MYC and AKT activation, and S3 was associated with hepatocyte differentiation. Functional studies indicated that the WNT pathway activation signature characteristic of S1 tumors was not simply the result of beta-catenin mutation, but rather was the result of TGF-beta activation, thus representing a new mechanism of WNT pathway activation in HCC. These experiments establish the first consensus classification framework for HCC based on gene-expression profiles, and highlight the power of integrating of multiple datasets to define a robust molecular taxonomy of the disease.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, transcriptome, meta-analysis, transforming growth factor-beta, WNT pathway

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) affects approximately half a million patients worldwide, and is the most rapidly increasing cause of cancer death in the U.S. owing to the lack of effective treatment options for advanced disease (1). Numerous lines of clinical and histopathoogical evidence suggest that HCC is a heterogeneous disease, but a coherent molecular explanation for this heterogeneity has yet to be reported. Genomic approaches to the classification of HCC therefore hold promise for a molecular taxonomy of the disease.

Mutations in the WNT signaling pathway have been found to be common in HCC, but other DNA-level classification approaches have proven challenging. This relates to the enormous complexity of the genomic alterations observed in HCC, likely attributable to the accumulation of chromosomal rearrangements resulting from decades of chronic viral hepatitis and cirrhosis. This complexity makes it difficult to identify the causal genetic events promoting HCC development and progression (2, 3). An alternate approach to HCC classification has been to study tumors at the level of their gene expression profiles. While a number of such profiling efforts have been reported (4–11), a cohesive view of expression-based subclasses of HCC has yet to emerge. In part, this is because each of the reported studies analyzed different patient populations (most of them small) on a different microarray platform, with a different primary biological or clinical question in mind. Perhaps not surprisingly then, each study reported a somewhat different view of the heterogeneity of HCC, and it has been therefore impossible to see whether there exists a common biological thread that links these disparate studies.

We believe that any biologically- or clinically-meaningful classification system should be informative across multiple patient populations, and should be independent of any particular microarray platform. In the present study, we therefore set out to define molecular subclasses of HCC that existed across all available HCC datasets, including 8 previously reported studies and one new one reported here, totaling 603 patients. We report that indeed there exist 3 distinct molecular subclasses of HCC that are present in all 9 datasets examined – regardless of technical differences between the microarray platforms used to generate the profiles. We show that these subclasses are correlated with histologic, molecular and clinical features of HCC, and we highlight the important role of TGF-beta signaling in one of the HCC subclasses. These findings thus create a solid foundation for HCC classification on which to build informed clinical trials for patients with HCC, and also suggest new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Microarray datasets and statistical analysis

Identification of common HCC subclasses

To define and validate a gene expression-based model of common molecular subclasses of HCC, we collected publicly available gene expression datasets from eight independent cohorts profiled on a wide variety of microarray platforms (HCC-A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H (4–11), see Supplementary Table S1 and S2 for details). Between the training datasets (HCC-A, B, and C) chosen as larger datasets covering major etiologies of HCC to avoid overfitting a model to any particular cohort or microarray platform, corresponding subgroups of the samples were defined by Subclass Mapping (SubMap) method (12) based on subclasses identified three unsupervised clustering methods: hierarchical clustering, k-means clustering, and non-negative matrix factorization (NMF), which finds clusters of samples after collapsing the dataset into representative “meta-genes” (13).

For each subclass defined by SubMap, meta-analysis marker genes were selected as overexpressed genes compared to the rest of the subclasses (HCC subclass signature) in all the three clustering methods to avoid defining gene expression-based subclasses that were unique to a particular clustering algorithm. Prediction of the subclass was performed for each sample using nearest template prediction method (14, 15) to accommodate the diverse microarray platforms (see Supplementary Information for the details).

Molecular annotation of HCC subclasses

Functional characterization of the HCC subclasses was performed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (16). Two categories of gene sets in Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB, http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/msigdb/) were used: target gene sets regulated by experimental perturbations (377 gene sets), and literature-based manually curated molecular pathway gene sets (150 gene sets).

Clinical data analysis

The hazard of tumor recurrence was calculated to estimate the pattern of HCC recurrence over time after the surgery as previously reported (17, 18). Continuous and proportional data were tested by Wilcoxon rank sum test and Fisher's exact test, respectively. All clinical data analyses were performed using the R statistical package version 2.4.0 (www.r-project.org).

Microarrays for fixed tissues

We generated a ninth dataset of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumors (HCC-I), reasoning that any meaningful classification system should be applicable to routinely-collected fixed (as opposed to frozen) tissues. We analyzed FFPE tissue blocks from 118 HCC patients who consecutively underwent surgical resection during 1990–2001 at Toranomon Hospital, Japan. Ethical approval for use of the FFPE tissues, obtained and archived as part of routine clinical care, was acquired from the institutional review board granted on condition that all samples be made anonymous. Total RNA was extracted from macro-dissected 10 micron tissue slices (3~4 slices for each sample) using High Pure RNA Paraffin kit (Roche). Expression of transcriptionally-informative 6,000 genes, selected to capture global state of transcriptome (14), were profiled using DNA-mediated Annealing, Selection, Extension and Ligation (DASL) assay (19) (Illumina) (see Supplementary Information).

Microarrays for cell lines

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instruction. Microarray experiment was performed using HT_HG-U133A High-Throughput Arrays (Affymetrix). The raw data were normalized using BioConductor's affy package (http://www.bioconductor.org/).

All microarray datasets are available through NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession numbers of GSE10186 (DASL), GSE10393 (U133A), and GPL5474 (Transcriptionally Informative Gene panel for DASL), and our web site (http://www.broad.mit.edu/cancer/pub/HCC).

Immuno-staining

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 10 micron FFPE sections using antibodies for beta-catenin (BD), pAKT (Cell Signaling), and p53 (Immunotech) followed by detection using the Envision+ DAB system (Dako). The stains were evaluated by a pathologist blinded to the results of the gene expression profiling, and the results were scored in a binary system. For immunofluorescence staining, cells grown on multiwell chamber slides were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained for beta-catenin (see Supplementary Information for the details).

Cell culture

Human HCC cell lines, Huh-7 (Riken Bioresource Center, Japan) and SNU-387 (American Type Culture Collection), were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. No beta-catenin mutation has been found in these cell lines.

Western blotting

Cell lysates were separated on Nupage 4–12% gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Biorad), and blotted for AFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), beta-catenin (Becton Dickinson), phospho-SMAD3 (Cell Signaling), and PCNA (Santa Cruz) antibodies.

Beta-catenin knockdown

Cells were infected with the indicated shRNA vectors (construct #1: TRCN0000003843, #2: TRCN0000003844, The RNAi Consortium, www.broad.mit.edu/genome_bio/trc/rnai.html) and puromycin selected. 96 hours post-infection cells were counted and seeded in triplicate (20.000 cells/ 6 well). After 10 days, cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. Dye was extracted with 10% acetic acid and OD was determined at 600 nm.

Luciferase assay

Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine-2000 (Invitrogen) with either TOP-flash or FOP-flash constructs and stimulated with 100 pM of TGF-beta (R&D systems) for 48 hours. Luciferase activity was measured using Dual-Glo kit (Promega). All transfections were performed in triplicate and measurements were normalized to a SV40-promoter driven Renilla-luciferase construct.

Results

Three common molecular subclasses of HCC

The Subclass Mapping method identified 3 robust subclasses in each of the 3 initial datasets analyzed. We refer to these subclasses as S1, S2, and S3 (Fig. 1) and the complete list of genes correlated with each of the subclasses is available in Supplementary Table S3. As with any unsupervised clustering-based definition of cancer subclasses, it is essential to establish the validity of the newfound classification system. In the following sections, we describe three independent validations of the 3-class structure of HCC. First, we demonstrate that the 3 subclasses are detected with statistical significance in each of the 6 remaining HCC datasets (totaling 371 patients). Second, we demonstrate that the subclasses are associated with clinical parameters. Third, we demonstrate that the subclasses are associated with biological mechanism known to be operative in the pathogenesis of HCC.

Fig. 1. HCC subclasses predicted in nine independent datasets.

Predicted subclasses are shown in red (S1), blue (S2) and yellow (S3) with expression pattern of the HCC subclass signature. The proportion of the cases with confident prediction (FDR < 0.05) in HCC-A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and I were 96%, 96%, 90%, 81%, 79%, 87%, 94%, 83%, and 83%, respectively. Red bars attached to HCC-H and HCC-I indicate positive beta-catenin mutations and nuclear staining of p53, respectively. FDR: false discovery rate.

Statistical validation of subclasses across 9 HCC cohorts

As a statistical measure of the validity of the 3 subclasses, we determined the confidence with which HCC samples could be classified into one of the three subclasses using the HCC subclass signature-based classifier including 619 genes. As expected, subclass labels were assigned with high confidence (FDR<0.05) to 94% of the training samples (HCC-A~C) which were used to define the subclasses in the first place. More importantly, high confidence subclass labels were assigned to 84% of the 371 samples in the validation set (HCC-D~I). In contrast, a classifier based on the same number of genes chosen randomly yielded high confidence predictions in fewer than 1% of the samples. In addition, our classification system was superior to those reported previously (10, 11, 20, 21), when those classifiers were tested across all of the validation datasets (high confidence predictions using reported signatures were 27~75%, Supplementary Fig. S1). These results, taken together, indicate the statistical significance of our 3 subclasses, and point to the limitation of defining subclasses based on only a single cohort, where overfitting often leads to failure of the classifier to validate on new samples – particularly when profiled on a different microarray platform.

Clinical relevance of HCC subclasses

Having established the statistical validity of the HCC subclasses, we next asked whether any of the subclasses were associated with clinical parameters to add the validity of the subclasses. Clinical data were available for 197 patients, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical phenotypes associated with HCC subclasses

| Variable | S1 | S2 | S3 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size (cm)* | 3.0 [2.0,4.5] | 4.5 [2.5,7.0] | 2.5 [1.8,4.3] | 0.003 | |

| Tumor differentiation* | Well | 8 (16%) | 4 (10%) | 37 (44%) | |

| Moderate | 27 (53%) | 23 (59%) | 45 (53%) | <0.001 | |

| Poor | 16 (31%) | 12 (31%) | 3 (4%) | ||

| alpha-fetoprotein (ng/ml)† | 50 [14,332] | 171 [27,1251] | 13 [5,43] | <0.001 | |

| Hepatitis B virus infection‡ | 39 (38%) | 27 (36%) | 39 (25%) | 0.05 | |

| Hepatitis C virus infection‡ | 55 (53%) | 44 (58%) | 109 (69%) | 0.03 |

Median [25%,75%]

: HCC-F, H and I. S1: n=55, S2: n=46, S3: n=96

: HCC-H and I. S1: n=48, S2: n=39, S3: n=83

: HCC-B, C, F, H and I. S1: n=103, S2: n=76, S3: n=158

Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous data, Fisher's exact test for categorical data

Our first observation was that tumors in subclass S2 were larger than the others, whereas tumors in S3 were smaller compared to the rest (p=0.003). In addition, subclass S3 included the majority of well-differentiated tumors (37/49, p<0.001), whereas there was no histological difference between S1 and S2 (p=0.73). We also examined the serum levels of the one clinically-used serum biomarker of HCC, alpha fetoprotein (AFP). Serum AFP was the highest in S2 (p<0.001), further supporting the notion that our subclasses are clinically relevant.

Next we sought to determine whether the HCC subclasses were associated with clinical outcome following surgical resection. We were careful to analyze the two major patterns of HCC recurrence: early recurrence, which is related to residual dissemination of primary tumor cells within the liver, and late recurrence, which is attributable to new primary tumors arising in a hypercarcinogenic state of a cirrhotic liver (17, 18, 22). “Early” recurrence is known to be associated with malignant characteristics of the primary tumor itself, and we reported that it has less impact on patient survival in earlier stage HCC, in which “late” recurrence is the major determinant of survival (14, 23). We found that subclass S1 was associated with a significantly greater risk of earlier recurrence (p=0.03 within 1 year) (Supplementary Fig. S2). This association remained to be significant even after correcting for tumor size in multivariate Cox regression modeling (Supplementary Table S4). Consistent with this observation, S1 tumors exhibited more vascular invasion and satellite lesions (both known risk factors for early recurrence) (Supplementary Table S5). These results may suggest that the S1 subclass is associated with a more invasive/disseminative phenotype. Interestingly, we found that a recently reported signature of poor survival defined in patients with more advanced HCC, where “early” recurrence is the major determinant of survival (4), was associated with S1 and S2, whereas the good survival signature defined in that study was enriched in S3 tumors (Supplementary Table S6), lending further credence to our subclass model. Importantly, our HCC subclasses were not associated with late recurrence, consistent with our recent study indicating that late recurrence is determined not by the characteristics of the tumor itself, but rather by the biological state of the surrounding liver at risk (14). Furthermore, consistent with our previous observation, the HCC subclasses showed no association with survival (p=0.12) in our dataset (HCC-H) consisting mostly of early stage tumors.

Molecular pathways associated with HCC subclasses

We next asked whether we could ascribe biological meaning to our validated HCC subclasses. The GSEA results indicated that indeed our HCC subclasses were associated with distinct biological processes, several of which have been implicated in HCC pathogenesis (Supplementary Tables S7 and S8). For example, S2 were tumors associated with a relative suppression of interferon target genes (7), of interest because of the use of interferon as an experimental chemopreventive strategy for HCC. S2 tumors were also enriched in MYC target genes, suggesting that MYC activation is a feature of S2 tumors. Consistent with this observation, we found that a recently reported mouse model of HCC based on MYC overexpression (24) exhibited the S2 subclass signature (Supplementary Fig. S3). S2 tumors were also strongly enriched in a signature of EpCAM positivity (25) (Supplementary Table S6), and in addition, we found that S2 tumors overexpressed AFP (consistent with S2 patients having elevated serum AFP levels, Table 1). Lastly, S2 tumors were enriched in a signature of AKT activation (10), and validation experiment indicated a trend toward elevated phosphorylation of AKT as determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2A, p=0.07). An AFP-AKT association has been previously observed (10, 26), and we see here that this association is being driven primarily by S2 tumors. The mechanism of AKT activation in these tumors is not known, but likely reflects upstream signaling of the PI3 kinase pathway (27). As PI3 kinase inhibitors are now entering clinical development, it may be of value to examine their role in S2 tumors in particular.

Fig. 2. Molecular pathways associated with HCC subclasses.

Immuno-histochemistry analysis of (A) phospho-AKT, (B) p53, and (C) beta-catenin proteins in HCC-I. Left panels show proportions of the cases with positive staining in each HCC subclass. Right panels show representative positive staining (arrow heads, magnification: ×20). (D) Growth inhibition of SNU-387 cells (predicted to be subclass S1) by knocking down beta-catenin protein using two different shRNA constructs.

GSEA also identified differential activation of p53 and p21 target gene sets, with these genes being more abundantly expressed in S3 tumors compared to S1 and S2, consistent with our observation that S3 tumors tend to be lower grade (Table 1). To further validate this result, we performed immunohistochemistry for p53, wherein nuclear accumulation of p53 protein is well-known to reflect inactivating p53 mutation (28). As predicted by the GSEA analysis, S1 and S2 tumors exhibited significantly greater nuclear p53 staining compared to S3 (p=0.001; Fig. 2B). The more well-differentiated nature of S3 tumors was also reflected in the S3 gene expression profile, with S3 tumors exhibiting relatively higher levels of expression of hepatocyte function-related genes involved in glycogen/lipid/alcohol metabolism (APO/ALDH/ADH family genes), detoxification (CYP family genes), coagulation, and oxygen radical scavenging (CAT, SOD1) (Supplementary Table S3, S7, and S8),

WNT pathway activation in S1

The WNT signaling pathway is perhaps the best characterized oncogenic pathway in HCC, with pathway activation occurring through beta-catenin mutation (specifically via mutation in exon 3 in up to 44% of cases) and less frequently in AXIN1 (<10% of cases) (2, 3). We addressed WNT status with regard to HCC subclass in two ways. First, we performed GSEA analysis using an experimentally defined WNT activation signature. We found strong enrichment of the WNT signature in subclass S1 compared to S2 or S3 (FDR=0.03, Supplementary Table S7), suggesting preferential WNT activation in S1 tumors. We validated this result via immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin (the principle downstream effecter of WNT in HCC), and found that S1 tumors indeed had higher levels of cytoplasmic beta-catenin protein expression compared to the other subclasses (p<0.001), again indicating preferential activation of the canonical WNT pathway in S1 (29) (Fig. 2C). In addition, we found that shRNAs targeting beta-catenin resulted in growth inhibition when introduced into the SNU-387 cell line (predicted to be subclass S1), thereby further supporting the hypothesis that WNT activation is functionally important in S1 tumors (Fig. 2D).

Mechanisms of WNT activation in S1 tumors

Having determined that S1 tumors exhibit preferential activation of the WNT/beta-catenin pathway, we next addressed potential mechanisms for this activity. We first asked whether the S1 tumors were associated with beta-catenin mutation in HCC-H dataset, for which we previously sequenced exon 3 of beta-catenin gene(11). Surprisingly, beta-catenin mutations were preferentially found in S3 tumors, consistent with previously reported “CTNNB1” class representing a subset of S3 (11, 30). This result is also consistent with recent evidence indicating that beta-catenin mutations do not regulate the canonical WNT target genes (e.g., cyclin D1 and MYC) that characterize our S1-associated WNT activation signature (31). These results further suggest that the WNT pathway is activated in S1 tumors by a mechanism other than beta-catenin mutation.

To explore alternate explanations for WNT pathway activation, we again turned to GSEA, asking whether other gene sets (signatures) enriched in S1 tumors might provide insight into WNT activation in these tumors. Strikingly, we observed strong over-expression of TGF-beta target gene sets (that is, genes expressed as a result of experimental activation of TGF-beta) in S1 tumors (Supplementary Table S7). We similarly observed enrichment of a gene set associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a phenomenon implicated in tumor invasion and metastasis (32), and known to be regulated by TGF-beta signaling in HCC (Supplementary Table S7) (33, 34). Furthermore, a previously reported TGF-beta activation signature associated with an invasive phenotype (35) showed strong enrichment in S1 (Supplementary Table S6). We observed no genomic copy number change associated with S1 subclass in TGFB1 locus, suggesting that chromosomal aberration is not the causative mechanism of the activation (Supplementary Fig. S4). These results indicate that TGF-beta and WNT signaling co-occur in the same HCC subclass (subclass S1), and suggest the hypothesis that TGF-beta might in some way lead to WNT activity that defines the S1 molecular phenotype.

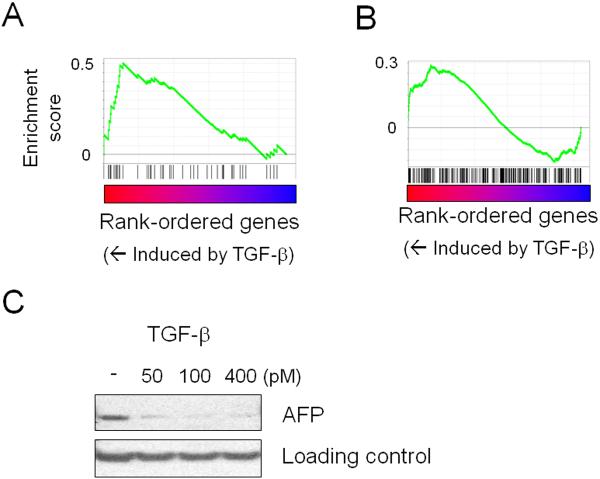

TGF-beta-WNT interactions

We next explored the hypothesis that TGF-beta regulates WNT pathway activity in HCC cells. First, we treated the HCC cell line Huh7 with intact WNT pathway components (classified as subclass S2 and with no activation of S1 and WNT activation signature) with TGF-beta, and monitored the genome-wide expression consequence. As predicted, TGF-beta stimulation induced expression of WNT target genes (FDR<0.001, Fig. 3A), and induced the expression of genes characteristic of subclass S1 (FDR=0.04, Fig. 3B, Supplementary Information) characterized by WNT/TGF-beta activity, while suppressing expression of AFP protein, one of the top markers for S2 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3. Interaction between WNT pathway and TGF-beta.

(A) Up-regulation of an experimentally-defined WNT target gene set, “KENNY_WNT_UP” (FDR<0.001), by TGF-beta. Genes were rank-ordered based on differential expression between TGF-beta-treated and untreated Huh-7 cells (predicted to be subclass S2). A database of target gene sets for experimental perturbations (377 gene sets) was assessed by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA).

(B) Up-regulation of the S1 signature by TGF-beta treatment. Genes were rank-ordered based on differential expression between treated and untreated Huh-7 cells, and induction of the subclass signature was evaluated by GSEA (FDR=0.04).

(C) Suppression of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) protein expression by TGF-beta treatment. Loading control is non-specific for AFP antibody to show that equal amounts of protein were loaded.

FDR: false discovery rate.

Second, we asked whether TGF-beta could regulate the activity of a TCF-LEF reporter, further reflecting WNT/beta-catenin activity. TGF-beta stimulation of Huh7 cells resulted in activation of a wild-type (TOP-Flash) but not mutant (FOP-Flash) TCF-LEF luciferase reporter (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the superactivation of TCF-LEF activity was also observed in the presence of co-transfected mutant beta-catenin. These results validate the hypothesis that TGF-beta enhances WNT activity in HCC, consistent with the subclass S1 molecular profile.

Fig.4. Activation of WNT pathway by TGF-beta.

(A) Huh7 cells were transfected with the indicated reporter constructs and increasing amounts of mutant beta-catenin (2, 5, 10ng of plasmid).

(B) TGF-beta pathway activation was confirmed by phosphorylation of SMAD3. Abundance of beta-catenin protein was not changed by TGF-beta treatment (100pM, 48h). Loading control is non-specific for phosphor-SMAD3 antibody to show that equal amounts of protein were loaded.

(C) Huh7 cells were stimulated as above and stained for beta-catenin. Cellular distribution of beta-catenin changed from predominantly membranous to cytoplasmic and perinuclear, and clustered cells spread out with more elongated and flattened morphology.

We next explored the mechanism by which TGF-beta augments WNT/beta catenin activity. A simple explanation would be that TGF-beta induced expression of beta catenin RNA or protein levels, but we found no evidence for this (Fig. 4B). Strikingly, however, TGF-beta treatment resulted in a marked change in beta-catenin subcellular localization. Specifically, TGF-beta treatment induced a shift from membranous beta-catenin staining to a cytoplasmic distribution with focal peri-nuclear aggregation (Fig. 4C). This suggests that TGF-beta enhances WNT signaling by modulating the intracellular pool of free beta-catenin.

Taken together, these results validate the observation that TGF-beta and WNT activity together typify the S1 subclass of HCC, and further suggest that TGF-beta augments WNT activity via alteration of the subcellular localization of beta-catenin, consistent with the cross-talk between these pathways observed in other biological contexts (34, 36). This implies that therapeutic co-targeting TGF-beta and beta-catenin in S1 tumors might be explored as a strategy for the treatment of S1 subclass HCC.

Discussion

Advances in genome technologies are now supporting a breadth of cancer genome characterization studies, including those focusing on HCC. Along with this proliferation of studies has come, however, a certain confusion in the field -- different studies often report different results relating to the same set of underlying questions. For example, about 10 papers on the gene expression-based classification of HCC have been published in recent years, but a consensus molecular taxonomy of the disease has yet to emerge. This might lead some to believe that either expression technologies are insufficiently stable, or HCC is so hopelessly heterogeneous and complex that regular, reproducible patterns in the data are non-existent. We report here that in fact a highly reproducible molecular architecture of HCC is identifiable, and is detected across all available HCC datasets.

Our analysis of 9 HCC datasets totaling 603 patients indicated that there exist three major subclasses of HCC, which we refer to as subclasses S1, S2 and S3 (Fig. 5). Importantly, while the proportion of each subclass varied slightly from study to study, the subclasses were identifiable regardless of the geographic location of the study patients (Asia vs. Europe vs. U.S.) or the technology platform utilized (cDNA vs. oligonucleotide arrays, and frozen vs. FFPE tissues). Notably, the new dataset generated in the present study utilized FFPE tissues, thereby demonstrating that the 3-class structure is readily detectible in specimens collected and stored in the routine clinical setting. This is relevant because the future deployment of diagnostic tests aimed at cancer classification should ideally be applicable to the standard FFPE specimens that are obtained in clinical practice.

Fig. 5. Schematic summary of the characteristics of HCC subclasses.

AFP: alpha-fetoprotein.

A number of biological insights can be made from the observed 3-class structure of HCC. Class S1 is particularly notable for the prominence of a WNT activation gene expression signature. This is notable because such WNT activation is not simply explained by the presence of activation beta-catenin mutations, suggesting that additional mechanisms of WNT activation appear to be at play, including TGF-beta activation. This may be particularly important in the setting of clinical trials testing beta-catenin inhibitors in HCC. Our data suggest that such inhibitors may be worth exploring in HCC beyond those patients harboring beta-catenin mutation. While additional mechanistic studies are clearly required, our data support the existence of an interaction between WNT activation and TGF-beta activation in S1 tumors – an interaction that has been recently proposed in HCC (34).

Class S2 tumors were notable for their high level of expression of AFP, associated with elevated plasma levels of AFP protein compared to non-S2 patients. S2 tumors also tended to be enriched in MYC tumors harboring a MYC activation signature. This is of relevance because it suggests that genetically-engineered mouse models of HCC based on MYC activation may be used to interrogate biological basis of the S2 subclass of human HCC. In addition, the finding of an AKT activation signature in S2 tumors suggests that AKT or PI3 kinase inhibitors might be particularly worthy of exploration in this subclass. Further studies are required to establish the mechanism by which AKT is activated in these tumors.

S3 tumors were notable for their relative histological evidence of differentiation, and the S3 gene expression program was accordingly suggestive of a molecular program of differentiated hepatocyte function. It is tempting to speculate that these tumors might be particularly well-suited to differentiation therapy with agents such as retinoids, as has been previously suggested (37). Whether S3 tumors have distinct mechanisms of transformation, or rather simply allow for more complete cellular differentiation remains to be determined. The preserved p53 function in S3 suggests that the abrogation of p53 is associated with stepwise malignant transformation of well-differentiated tumors rather than initiation of carcinogenesis. The less frequent beta-catenin mutations in S1 and S2 may suggest that these tumors arose through different carcinogenic mechanisms compared to S3.

Clearly, much remains to be learned about the biological basis of our observed HCC subclasses. But the fact that they are observed in all studies of HCC examined to date suggest that they represent a reproducible classification framework for the disease. We therefore propose that it will be important to know the subclass of HCC patients entering clinical trials for the treatment of HCC, because the response to targeted agents (e.g. beta-catenin, PI3kinase) are likely to be different across the subsets (38). Early observations of differential sensitivity of these distinct tumor types may help guide the design of future clinical trials aimed at targeting agents to distinct patient populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Menno Creyghton for reagents and helpful suggestion; So Young Kim, Ron Firestein, William Hahn, and David Root for the shRNA constructs; Megan Hanna for technical help; Weijia Zhang for critical reading of the manuscript; Jadwiga Grabarek and Mariko Kobayashi for general support.

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Cancer Institute (T.R.G., NIH/NCI: 5U54 CA112962-03), National Institute of Health (J.M.L., NIDDK 1R01DK076986), and Spain National Institute of Health grant I+D Program (J.M.L., SAF-2007-61898), and Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation. Yujin Hoshida is supported by Charles A. King Trust fellowship. Sebastian Nijman was supported by NWO (Rubicon) and KWF fellowships.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JS, Chu IS, Heo J, et al. Classification and prediction of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma by gene expression profiling. Hepatology. 2004;40:667–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Cheung ST, So S, et al. Gene expression patterns in human liver cancers. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1929–39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0023.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iizuka N, Oka M, Yamada-Okabe H, et al. Oligonucleotide microarray for prediction of early intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Lancet. 2003;361:923–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breuhahn K, Vreden S, Haddad R, et al. Molecular profiling of human hepatocellular carcinoma defines mutually exclusive interferon regulation and insulin-like growth factor II overexpression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6058–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye QH, Qin LX, Forgues M, et al. Predicting hepatitis B virus-positive metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2003;9:416–23. doi: 10.1038/nm843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Midorikawa Y, Tsutsumi S, Nishimura K, et al. Distinct chromosomal bias of gene expression signatures in the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7263–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyault S, Rickman DS, de Reynies A, et al. Transcriptome classification of HCC is related to gene alterations and to new therapeutic targets. Hepatology. 2007;45:42–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6779–88. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshida Y, Brunet JP, Tamayo P, Golub TR, Mesirov JP. Subclass mapping: identifying common subtypes in independent disease data sets. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunet JP, Tamayo P, Golub TR, Mesirov JP. Metagenes and molecular pattern discovery using matrix factorization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4164–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308531101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1995–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L, Shen SS, Hoshida Y, et al. Gene expression changes in an animal melanoma model correlate with aggressiveness of human melanoma metastases. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:760–9. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, et al. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Hepatol. 2003;38:200–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzaferro V, Romito R, Schiavo M, et al. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence with alpha-interferon after liver resection in HCV cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;44:1543–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan JB, Yeakley JM, Bibikova M, et al. A versatile assay for high-throughput gene expression profiling on universal array matrices. Genome Res. 2004;14:878–85. doi: 10.1101/gr.2167504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaposi-Novak P, Lee JS, Gomez-Quiroz L, Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Met-regulated expression signature defines a subset of human hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis and aggressive phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1582–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI27236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JS, Heo J, Libbrecht L, et al. A novel prognostic subtype of human hepatocellular carcinoma derived from hepatic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:410–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Llovet JM. Molecular profiling to predict hepatocellular carcinoma outcome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:101–3. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JS, Chu IS, Mikaelyan A, et al. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1306–11. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamashita T, Forgues M, Wang W, et al. EpCAM and alpha-fetoprotein expression defines novel prognostic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1451–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahin F, Kannangai R, Adegbola O, Wang J, Su G, Torbenson M. mTOR and P70 S6 kinase expression in primary liver neoplasms. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8421–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Newell P, et al. Pivotal Role of mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vousden KH, Lane DP. p53 in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:275–83. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller JR, Moon RT. Signal transduction through beta-catenin and specification of cell fate during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2527–39. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorgeirsson SS, Lee JS, Grisham JW. Functional genomics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2006;43:S145–50. doi: 10.1002/hep.21063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zucman-Rossi J, Benhamouche S, Godard C, et al. Differential effects of inactivated Axin1 and activated beta-catenin mutations in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26:774–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zavadil J, Bottinger EP. TGF-beta and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene. 2005;24:5764–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giannelli G, Bergamini C, Fransvea E, Sgarra C, Antonaci S. Laminin-5 with transforming growth factor-beta1 induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1375–83. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer AN, Fuchs E, Mikula M, Huber H, Beug H, Mikulits W. PDGF essentially links TGF-beta signaling to nuclear beta-catenin accumulation in hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Oncogene. 2007;26:3395–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Transforming growth factor-beta gene expression signature in mouse hepatocytes predicts clinical outcome in human cancer. Hepatology. 2008;47:2059–67. doi: 10.1002/hep.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jian H, Shen X, Liu I, Semenov M, He X, Wang XF. Smad3-dependent nuclear translocation of beta-catenin is required for TGF-beta1-induced proliferation of bone marrow-derived adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Genes Dev. 2006;20:666–74. doi: 10.1101/gad.1388806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muto Y, Moriwaki H, Ninomiya M, et al. Prevention of second primary tumors by an acyclic retinoid, polyprenoic acid, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1561–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606133342402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48:1312–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.