Abstract

Research in microgravity is indispensable to disclose the impact of gravity on biological processes and organisms. However, research in the near-Earth orbit is severely constrained by the limited number of flight opportunities. Ground-based simulators of microgravity are valuable tools for preparing spaceflight experiments, but they also facilitate stand-alone studies and thus provide additional and cost-efficient platforms for gravitational research. The various microgravity simulators that are frequently used by gravitational biologists are based on different physical principles. This comparative study gives an overview of the most frequently used microgravity simulators and demonstrates their individual capacities and limitations. The range of applicability of the various ground-based microgravity simulators for biological specimens was carefully evaluated by using organisms that have been studied extensively under the conditions of real microgravity in space. In addition, current heterogeneous terminology is discussed critically, and recommendations are given for appropriate selection of adequate simulators and consistent use of nomenclature. Key Words: 2-D clinostat—3-D clinostat—Gravity—Magnetic levitation—Random positioning machine—Simulated microgravity—Space biology. Astrobiology 13, 1–17.

1. Introduction

Research under the conditions of microgravity during space missions has contributed greatly to our knowledge of the impact of gravity on biological processes, gravity-sensing mechanisms, and gravity-mediated orientation of organisms in their spatial environment. These processes, however, are far from being fully understood. This is mainly due to the fact that access to flight opportunities is scarce, and performing a sufficient number of experiments or even a series of succeeding experiments has been realized only sporadically. In addition, clear-cut distinctions between gravity-related effects and stress responses to free-fall conditions are lacking. While the currently applied “-omics” technologies produce huge amounts of data, it remains unclear up to now what exactly to look for. This strongly emphasizes the need for ground-based facilities (GBFs) to define baselines and enable thorough testing of the biological system to address gravity-related issues prior to space experiments.

Since the introduction of the classical clinostat in 1879 by Julius Sachs, a number of GBFs have been designed to simulate the condition of “weightlessness” or “free fall” in laboratories on Earth. Such simulators do not abolish the 1g force of gravity but instead either randomize the direction of gravity with respect to the sample over time (omnilateral stimulation—clinostat principle) or compensate the gravity force by creating a counteracting force (magnetic levitation). On the ground, only drop towers are able to provide real free-fall conditions for a period of seconds.

In recent decades, numerous experiments have been performed with different types of simulators and a great variety of organisms. Simulator experiments have provided excellent insight into a multitude of gravity-dependent phenomena. However, many researchers failed to compare results from experiments in the “real” microgravity of a spaceflight mission with experiments on simulators, with respect to the sample used and to the parameters investigated, which represents the only way to unambiguously verify the suitability of the facility for simulating microgravity conditions of space. Without this direct comparison, it is difficult to conclude whether biological reactions or organismic responses are caused by the conditions of simulated microgravity or by any of the possible side effects of the simulation technique. Each type of simulator has its specific artifacts, for example, centrifugal accelerations and vibrations in the case of clinostats or differing magnetic susceptibility of cell components in the case of magnetic levitation, that may mask or distort the desired microgravity effect. Noncritical use of simulators may easily result in a misinterpretation of responses to side effects as specific microgravity effects. Comparing results from experiments in which samples were investigated on different simulators often revealed inconsistent or even contradicting responses. Therefore, for each simulator, the physical parameters and principles as well as their specific impact on the biological processes and objects of different sizes need to be critically evaluated. The different simulators and different modes of operation of simulators are not equally suited to simulate microgravity for all processes and organisms.

This comparative study gives an overview of the most frequently used microgravity simulators and illustrates their individual capacities and limitations. The range of applicability of the various ground-based microgravity simulators for different biological specimens was carefully evaluated by using organisms that have been studied extensively under the conditions of real microgravity in space. Since some papers suffer from inadequate descriptions of how the simulators were operated and which stimulations (i.e., accelerations and/or shearing forces) the samples were subjected to, current heterogeneous terminology is discussed critically, and recommendations are given for a proper selection of adequate simulators and consistent use of terminology.

2. Simulated Microgravity

First, we address nomenclatorial issues. Using experimental platforms such as two-dimensional (2-D) clinostats, rotating wall vessels (RWVs), random positioning machines (RPMs), and so on, the authors mainly use the term “simulated microgravity” or “simulated weightlessness” to describe the state of acceleration, which is assumed to be achieved with such machines. Sometimes, different phraseology is used for the same phenomenon/basic physical principle. For instance, the 2-D clinostat has been defined as a tool to obtain a “vector-averaged gravity” (e.g., Sarkar et al., 2000; Nakamura et al., 2003) or to provide the “nullification of the gravity stimulus” (Dedolph et al., 1967). Further terms are “modeled microgravity” (e.g., Plett et al., 2004; Zayzafoon et al., 2004), “near-Earth free-fall orbit” (Zayzafoon et al., 2004), “microweight simulator” (as a synonym for the RPM; van Loon et al., 1999), “randomized microgravity” (RPM; England et al., 2003), or “low shear environment” (Hammond and Hammond, 2001; Nickerson et al., 2004). Other authors refrain from judging the acceleration achieved with a simulation technique and therefore use a wording that exactly describes the experimental methods, such as “clinorotation” or “wall vessel rotation” (e.g., Anken et al., 2010; Brungs et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011). From the physical point of view, “Microgravity is the condition in which the absolute sum of all mass-dependent accelerations does not exceed a certain small ‘noise’ level (typically 10−5-10−6 times g)” (Albrecht-Buehler, 1992). Weightlessness also has been described as “no mechanical support of mass” (Briegleb, 1992) and as a “result from a net sum of all forces present equaling zero, not from absence of gravity” (Klaus, 2001). The latter definition can be misleading since in “microgravity” not all forces need to be equal to zero. One still has, for example, capillary forces, hydrostatic pressure, and cell surface binding forces (Albrecht-Buehler, 1991).

The term “microgravity” (or “micro-g environment,” or “μg”) is frequently used as a synonym of “weightlessness” and “zero-g,” which indicates that the g-forces are not actually zero but just “very small.” “True” weightlessness, for more than a few seconds at least, can only be achieved in space. In practice, space experiments require a space vehicle (e.g., ISS, shuttle). Inside the vehicle, the quality of weightlessness is influenced by so-called “g-jitters,” that is, vibrations caused by onboard machinery, movement of astronauts, thruster operation, and so on. The “microgravity” level may range between ∼ 10−3 to 10−6 g, depending on the location within the spacecraft and the frequency of vibration (Tryggvason et al., 2001; Penley et al., 2002; Jules et al., 2004). In life-science experiments, we are interested in the impact of mechanical stresses generated through the force of gravity on the mass of the organism. In short, we are investigating the impact of weight on biological systems. As a consequence, the best description of the environment would be “near weightlessness.” Terms such as “zero-g” or “weightlessness” should be avoided since we can never achieve such a level for more than a few seconds with space vehicles or ground-based simulations.

In simulation experiments, the magnitude of the Earth gravity vector cannot be changed—only its influence or effect can be changed (Briegleb, 1992). In consequence, microgravity cannot be achieved with a simulator. Rather, such a simulator may generate functional weightlessness from the perspective of the organism or cell. The term “functional near weightlessness” may thus be applied when the physical environment results in physical constraints that are (according to Briegleb, 1992) below the known acceleration sensitivities of relevant biological processes. Functional weightlessness has also been described as “a state of relative motionlessness which is defined with respect to the simultaneous contributions of gravity, centrifugation and Brownian motion acting on the suspended cell” (Klaus et al., 1998). By analogy, this description is also regarded to be valid for multicellular organisms.

To avoid confusion and provide a basis for acceptance, we propose here to use the term “simulated microgravity” (in analogy to microgravity conditions in spaceflight). Figure legends should explain clearly the GBF used and the main parameters to reproduce the simulation (geometry of the sample container, mode of operation and rotational speeds for RPM/clinostat, magnetic field intensity, and gradient in each position for the magnet as well as residual accelerations or effective radius).

We propose that the term “microgravity” should be assigned exclusively to those experiments that have been performed in an environment such as that of the International Space Station (ISS), satellites, sounding rockets, drop towers, or aircraft during parabolic flight. Parabolic flights offer a special experimental scenario, as the microgravity phases are interrupted by phases of hyper-g accelerations, which thereby demands careful control experiments in order to discriminate both kinds of effects on the sample. Usage of the term “microgravity” is independent of the actual acceleration (real microgravity, i.e., ∼10−6 g, is not, in fact, achieved in most of the environments listed above). The term “simulated microgravity,” thus, should be used regarding experiments performed in GBFs, in which the gravity level may be averaged to near zero with time but not neutralized.

3. Microgravity Simulators

Various GBFs with different physical concepts have been constructed to simulate microgravity on the ground. A description and the mode of operations of the most well-used facilities in Europe is given. In principle, organisms of all evolutionary levels can be used with these facilities: sessile organisms like plants or moving/swimming ones (e.g., small animals, protists, or bacteria) and cell cultures. Restrictions are given by the maximum volume of exposure and the quality of simulation the experimenter wants to achieve. One of the major problems that arises when comparing the different experimental designs and results is the lack of detailed technical descriptions of the operational modes (speed and direction of rotation) of the simulation facilities used in some of the literature. In addition, details on the hardware (material, dimensions, location within the GBF) are frequently missing.

In this study, the following simulation techniques were used for comparative studies with various biological model systems:

(1) 2-D clinostat

(2) Random positioning machine (RPM)

(3) Rotating wall vessel (RWV)

(4) Diamagnetic levitation

3.1. Clinostats—one or two axes running fast and constantly in one direction

A clinostat is a device in which samples are rotated to prevent the biological system from perceiving the gravitational acceleration vector. Different configurations exist with respect to the number of rotation axes, the speed, and the direction of rotation (Briegleb, 1992; Häder et al., 1995; Klaus et al., 1997; Klaus, 2001). Clinostats with one rotation axis, which runs perpendicular to the direction of the gravity vector, are called 1-D (seldom) or 2-D clinostats (more common). 1-D or 2-D refers to whether the dimension of the rotated line or the whole area is considered. Clinostats with two axes are called three-dimensional (3-D) clinostats and will be considered in the section “Random positioning machine.”

The use of clinostats in plant research began with experiments that rotated the object relatively slowly (1–10 rpm; classical clinostat). Seedlings and small plants rotated slowly in the 2-D clinostat axis did not exhibit any gravitropic response. However, later on, morphological studies demonstrated that slow clinorotation (1–2 rpm) induces disturbances at the ultrastructural level, which were not found under spaceflight conditions (Hensel and Sievers, 1980). These are indications that the slow rotation prevented a gravity-induced growth response but most likely also caused omnilateral mechanical stress in some sensitive plant tissues.

Briegleb introduced the concept of a fast rotating clinostat to achieve “functional weightlessness” for small objects, mainly single cells (Briegleb, 1992). By fast and constant rotation it is assumed that sedimentation is prevented physically by a continuous and constant change of the direction of the gravity vector. The principles can be demonstrated by rotating particles in a small tube or cuvette vertically positioned in the horizontal axis (running through its geometric center). In this arrangement, particles are forced to move on circular paths, whose diameters decrease with speed of rotation and finally reach a state in which relative movements with respect to gravity can be neglected. That is, a speed can be achieved at which a cell rotates around its center together with a small liquid boundary layer surrounding it (Klaus, 2001).

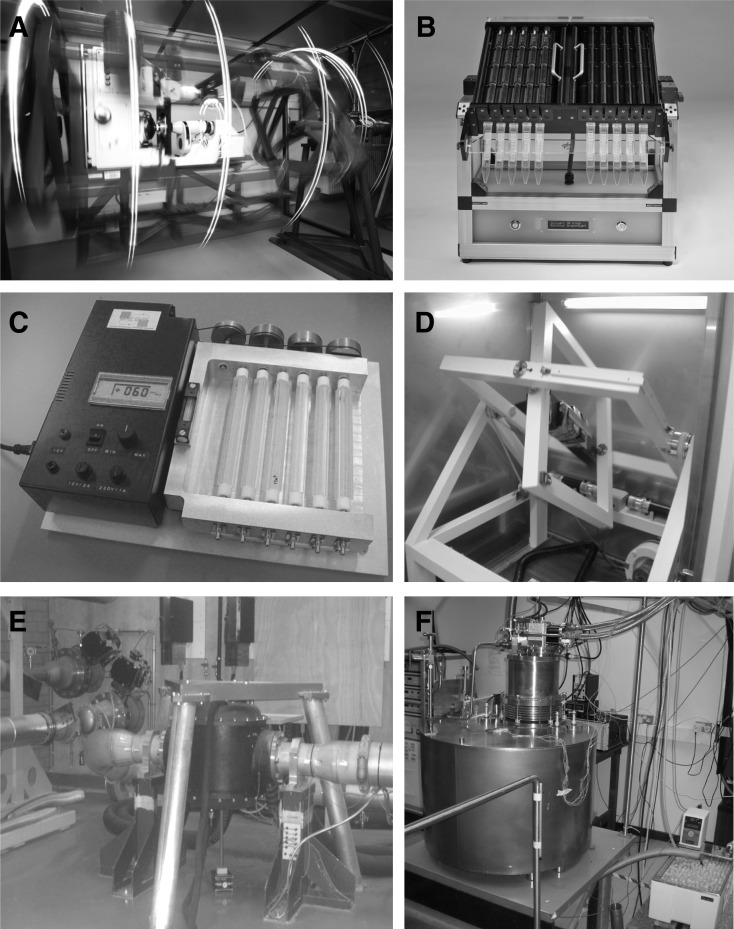

Under these conditions, biological samples no longer seem to have the capacity to perceive gravity and, thus, experience simulated microgravity. Depending on the scientific questions and methodological demands, different kinds of clinostats, besides the regular clinostats (Dedolph et al., 1967; van Loon et al., 1999; Hemmersbach et al., 2006), have been developed, which have enabled, for example, microscopic observation (clinostat microscope, Fig. 1A), online kinetic measurements (photomultiplier clinostat, Horn et al., 2011), fixation during rotation (pipette clinostat, Fig. 1B), and developmental studies under submersed conditions (submersed clinostat, Hemmersbach et al., 2006; Brungs et al., 2011) or even portable clinostats (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Images of the 2-D clinostat microscope (A) and the pipette 2-D clinostat (B) hosted at DLR, Cologne, Germany; the 2-D clinostat (C) and the 3-D RPM (D) hosted at DESC/ESA-ESTEC, Noordwijk, the Netherlands; and the two magnetic levitation facilities hosted at the HFML, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, (E) and the University of Nottingham, UK (F).

3.2. Random positioning machine—two axes running with different speeds and directions

Based on the hypothesis that the quality of simulation might be increased by rotating around two axes, especially for larger objects, so-called 3-D clinostats have been developed in Japan and in the Netherlands (for review see van Loon, 2007). These 3-D systems have two independently rotating frames (Fig. 1D). The term “3-D clinostat” is appropriate as long as the device is running with constant speed and constant direction (simplest RPM mode of function). However, both frames can also be operated with different speeds and different directions. In this case, the term “random positioning machine” (RPM) in combination with operational mode description should be used. These facilities are characterized by the randomly changing rotation speed and direction (Hoson et al., 1997; Borst and van Loon, 2009).

3.3. Rotating wall vessel

Rotating wall vessels (RWVs) or rotating bioreactors (Rotating Cell Culture System, initially developed by NASA) have been designed for cell cultures (Schwarz et al., 1992) and aquatic organisms such as zebrafish eggs/embryos (Moorman et al., 1999; Li et al., 2011). The submersed version of the RWV used in this comparative study was designed and constructed at the German Aerospace Center (Brungs et al., 2011). Main components are a Plexiglas cylinder (diameter of 10 cm) with a 5 cm wide central core, mounted on a horizontal plane. A shaft is connected to a variable speed motor.

3.4. Diamagnetic levitation

In 1997, Andre Geim, along with researchers from the Universities of Nijmegen and Nottingham, succeeded in levitating a live frog in a high field magnet at the High Field Magnet Laboratory (HFML), Nijmegen, using the diamagnetism of the frog (Berry and Geim, 1997; Geim, 1998; Simon and Geim, 2000); in the same year, Valles et al. at Brown University, USA, demonstrated diamagnetic levitation of frogs' eggs (Valles et al., 1997). These were followed by studies of levitating yeast (Coleman et al., 2007), swimming paramecia in gadolinium solution (Guevorkian and Valles, 2006b), E. coli (Dijkstra et al., 2011), cell cultures (Babbick et al., 2007; Hammer et al., 2009; Qian et al., 2009), a mouse (Liu et al., 2011), and Drosophila melanogaster (Herranz et al., 2012; Hill et al., 2012).

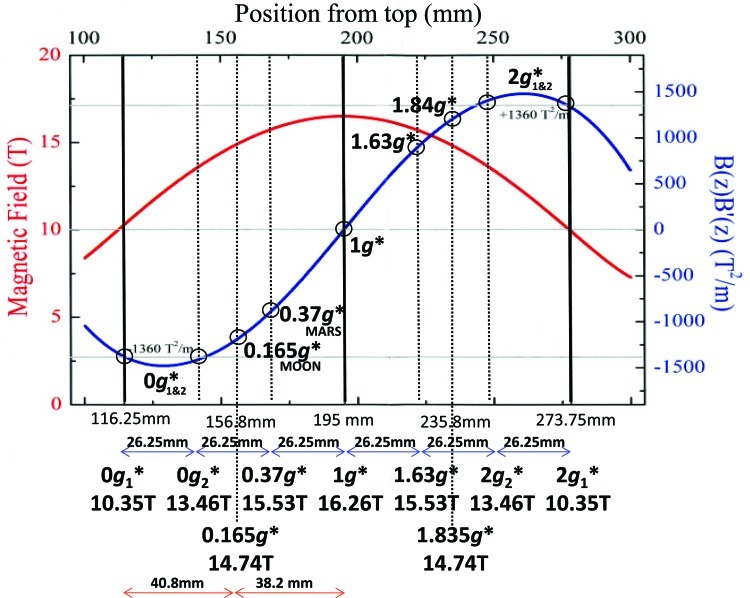

Diamagnetic levitation requires a strong, spatially varying magnetic field, such as that produced by a Bitter solenoid or a superconducting solenoid magnet. For levitation of biological material, a vertical bore magnet, in which the solenoid axis is oriented vertically, is used. The bore of the magnet is a cylindrical hole, open at both ends, that passes through the center of the solenoid. Inside the bore, the magnetic field is strongest where the bore passes through the center of the solenoid. A diamagnetic material is one such as water, many organic-based materials (e.g., oils, plastics), and biological materials that are repelled from a magnetic field. Inside the upper section of the vertical magnet bore, diamagnetic material is repelled upward, away from the strong field near the center; in the lower section, diamagnetic material is repelled downward. The vertical repulsive force is proportional to the product of the magnitude of the magnetic field B and its vertical gradient ∂B/∂z, and to the magnetic susceptibility of the material. The field-gradient product B×∂B/∂z varies continuously within the bore; it is zero exactly in the center of the solenoid (where the gradient of the field is zero) and reaches a maximum near the top and bottom of the solenoid (Fig. 2). If the product B×∂B/∂z is large enough, the diamagnetic force can support the weight of the diamagnetic material, allowing levitation. This occurs when B×∂B/∂z equals ρμ0g/χ, where ρ and χ are, respectively, the density and volume magnetic susceptibility of the material, μ0 is the magnetic constant, and g is the gravitational acceleration. For example, the diamagnetic force on a droplet of water counteracts exactly the weight of the droplet where B×∂B/∂z=−1361 T2/m, in the upper region of the bore. One can achieve stable levitation by this technique; a diamagnetic material can be made to levitate at a particular point in space in stable equilibrium (Berry and Geim, 1997), with no mechanical means of support. The diamagnetic force balancing the force of gravity on a levitating object acts throughout its volume, just as the centrifugal force acts to balance the force of gravity on a weightless body in Earth orbit. In this respect, diamagnetic levitation is unlike flotation; a scuba diver who is neutrally buoyant under water will neither float nor sink, but the forces balancing gravity in this case act only at the surface. The diver still feels “internal” stresses owing to the downward pull of the lead weight belt and the upward-pulling force of the buoyancy jacket, for example. The aim of diamagnetic levitation is to reduce the gravitationally induced internal stresses to as near to zero as possible in order to approach a weightless environment. Fortunately, the magnetic susceptibility of most soft biological tissues differs from that of water by only 10% or less (Schenck, 1992) and levitate under approximately the same conditions as water. Levitation can reduce the stresses within such tissues by an order of magnitude compared to the stresses induced by the pull of normal gravity (Valles et al., 1997). There are, however, notable exceptions, for example, in experiments on seedling growth, which we discuss below.

FIG. 2.

An example of magnetic levitation experimental positions in relation to the intensity of the magnetic field (curve, left axis) and the net effective force (curve, right axis) along the length of the magnetic bore. Color graphics available online at www.liebertonline.com/ast

The effective gravity acting on a diamagnetic body in the magnetic field is defined as the net force, that is, the sum of the gravitational and magnetic forces, per unit mass. At a levitation point, the effective gravity is zero, and the material is weightless. For biological material in the magnetic field, it is sometimes useful to calculate the effective gravity acting on water, especially in cases where the magnetic susceptibility of all tissues of interest are similar to that of water. Particularly useful as reference points are the places in the magnetic field where the effective gravity on water is precisely zero and 1g. These are commonly labeled as the 0g* and 1g* points, respectively (depending on the configuration of the magnetic field, there can be more than one 0g* point, including ring-shaped or planar loci of such points). The asterisk is used as a reminder that the labels refer to the effective gravity on water, and also to indicate that there is a strong magnetic field present. The magnitude and direction of the effective gravity varies continuously throughout the bore of the magnet, owing to the spatial variation of the magnetic field. Magnetic levitation therefore can be used to tune the effective gravity and provides a means by which to create enhanced, reduced, or even inverted gravity (Heijna et al., 2007; Micali et al., 2012). Depending on the experiment, it may thus be useful to identify points in which the effective gravity acting on water is the same as the gravity on the Moon (0.17g*) or Mars (0.38g*), in the upper region of the bore or a hypergravity point (2g*) in the lower part of the bore, for example (Fig. 2). The 0g* point (or points) is a mathematically determined location in the magnetic field, where the forces on water balance exactly. Although the effective gravity on water is a useful starting point in discussions of the internal stresses within the organism, a more detailed discussion of the diamagnetic forces within the organism is often required to obtain a more accurate picture of the residual forces within the organism. The label 0g* should not be confused with the term “microgravity” (or “μg”) used to indicate the residual gravity “experienced” by an object in an orbiting spacecraft. The magnitude of the effective gravity typically increases by ∼0.01g per millimeter as one moves away from a 0g* point; the magnitude of the effective gravity at the surface of a levitating water droplet, with volume 1 mL, for example, is typically 10−2g (Hill and Eaves, 2010). Note that, in cases where the susceptibility of a particular biological structure of interest is widely different from that of water (i.e., significantly different from the average susceptibility of the bulk of the organism), it may not be useful to discuss the results in terms of the effective gravity on water at all. For example, in the case of levitation of Arabidopsis seedlings, although the plant levitates under approximately the same conditions as water, sedimentation of the starch-rich statoliths within the root-tip cells is not suppressed (as it is in spaceflight), and the roots continue to bend down in the direction of gravity. To suppress sedimentation of the statoliths, a field gradient product much larger than that needed to levitate the plant is required.

One can anticipate that a strong magnetic field alone may have significant effects on the behavior of living organisms; for example, the 7 T field inside a modern MRI scanner can make volunteers nauseous (Glover et al., 2007). In addition, strong magnetic fields are able to orient certain biomolecules in solution, such as tubulin, actin, and DNA (Maret and Dransfeld, 1985). By performing careful control experiments in different parts of the bore, it is possible to study and distinguish between effects of magnetically simulated weightlessness and any other effects of the strong magnetic field. Experiments may be conducted simultaneously, under different effective gravities, in the same magnet; in this case, the magnitude of the magnetic field in the 1g* samples is ∼30% larger than in the 0g* and 2g* samples. An additional experiment exposing 1g* samples to the same field as in 0g* and 2g* may be performed by repeating the 1g* experiment individually, using a lower solenoid current.

4. Biological Responses of Selected Organisms Exposed to Simulated Microgravity

In this study, a variety of organisms were investigated with different microgravity simulators (GBFs). The quality of simulation was assessed on the basis of comparison with results from experiments under conditions of microgravity during spaceflight missions. To determine the optimal GBF and the mode of operation, the threshold of gravisensitivity of the biological system should be known. However, this is not known in most cases and must be determined by space experiments with threshold acceleration profiles. The following examples (performed in the framework of an ESA GBF project) might be useful as a guide for choosing the proper microgravity simulator for a given biological system. Nevertheless, this list should not be considered exhaustive but some inspiration for investigators who wish to use their particular model systems in space biology or those who need to corroborate their results with previous literature. For instance, the microbiology community would benefit greatly from a critical and updated review of the related literature (Klaus et al., 1998; Beuls et al., 2009).

4.1. Paramecium and Euglena—unicellular free-swimming cells

The protists Paramecium (ciliate) and Euglena (flagellate) show distinct gravity-guided modes of behavior in the form of negative gravitaxis (orientation against the direction of the gravity vector) and gravikinesis (regulation of the swimming speed with respect to the swimming direction) (Machemer et al., 1991; Machemer and Bräucker, 1992; Lebert and Häder, 1996; Hemmersbach and Häder, 1999; Hemmersbach et al., 1999; Häder et al., 2005a, 2005b, 2006, 2010; Hemmersbach and Braun, 2007; Daiker et al., 2011). Studies in real microgravity have demonstrated the loss of these responses in a time frame of 1–2 min (Hemmersbach-Krause et al., 1993a, 1993b; Hemmersbach et al., 1996a, 1996b; Häder et al., 2005a). These unicellular systems respond quickly to changes of gravity conditions but also to further environmental stimuli such as mechanical disturbances, light, or temperature. Furthermore, they can be immobilized in order to study their sedimentation behavior. These are the main reasons why Paramecium has been chosen as a model system for our comparative studies. As all experimental platforms had been equipped with in vivo observation by video recording, a detailed computer analysis of the behavior of the exposed cells could be performed. Swimming cells were exposed in round observation chambers (radius 15 mm, 0.5 mm depth). In the 2-D clinostat, cells in the observation area of 1 mm radius were rotated at a speed of 60 rpm and thus experienced a centrifugal force of 4×10−3g at the outer perimeter of the observation area (6×10−2g at the perimeter of the chamber). Cuvettes were totally filled with fluid (culture medium) and cells; gas bubbles were carefully avoided.

In the magnet, the unicellular systems were studied in commercially available cuvettes [Hellma, Müllheim, Germany; 52×12.5 mm, 3.5 mm depth (Paramecium); 45×12.5 mm, 0.2 mm depth (Euglena)], owing to spatial restrictions within the magnet bore.

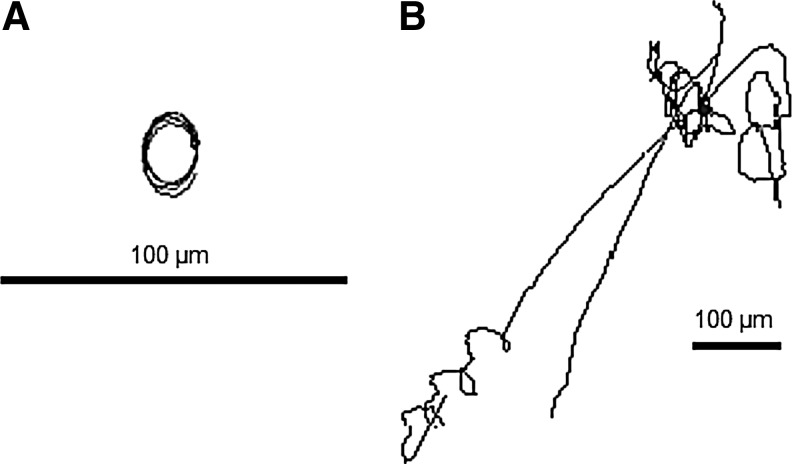

Two-dimensional clinorotation [60 rpm; clinostat microscope, German Aerospace Center (DLR) Cologne] revealed no change in the high linearity of the swimming paths of Paramecium comparable to the swimming pattern in real microgravity. Exposure on the RPM, however, indicated an increase in directional turns. The random speed and random direction mode on the RPM (Dutch Space, Leiden, the Netherlands) induced strong drifting and course corrections. Euglena cells, three times smaller than Paramecium, even drifted away passively, thereby making an analysis of the swimming velocities and the degree of orientation impossible. Two-dimensional clinorotation of immobilized cells (Paramecium) and glass beads resulted in a continuous circling, which demonstrated one-directional acceleration. The speed of the clinostat determined the diameter of the circles and thus the relative movements of the particles. In contrast, on the RPM, immobilized cells and beads were shown to bounce and move out of the rotation center (Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that samples on the RPM experience positive and negative acceleration forces induced by continuously changing the direction and speed of rotation.

FIG. 3.

Paths of glass beads (2–10 μm) in water during exposure on a fast rotating 2-D clinostat constantly running with 60 rpm (A) and a RPM with randomly varied speed and direction of the two frames (108°–120° s−1) (B). Notice the scale bars indicating the strong drifting in the RPM in this experimental setup (S. Hoppe, personal communication).

Paramecium and Euglena were exposed to high-gradient magnetic fields (HFML) with different magnetic field strengths (7–29 T) and field-gradient products up to −4160 T2/m. These experiments revealed a parallel and passive alignment of Paramecium to the static magnetic field, as a result of the magnetic alignment of anisotropic, structurally rigid components of the cells, consistent with the results of Guevorkian and Valles (2006a). In contrast, Euglena demonstrated a perpendicular orientation with respect to the applied field. The difference is caused by chloroplasts, as shown by the use of Astasia longa, a chloroplast-free Euglena, which did not show any magnetic alignment up to the highest magnetic fields used. Immobilized cells could not be levitated in the magnet for field-gradient products up to −4160 T2/m, as revealed by their sedimentation; due to the differences in densities and magnetic susceptibility of the protists and the surrounding water, the suppression of sedimentation does not coincide with levitation of water but should occur at higher values of the field-gradient product (e.g., −7000 T2/m, estimated for Paramecium; Guevorkian and Valles, 2006b).

We conclude that, for Paramecium and Euglena, the fast-rotating 2-D clinostat is a good simulator for microgravity, whereas the RPM is less suited. In the current configuration, the magnetic fields applied are not suited as a microgravity simulation for these two species of protists as levitation was not achieved and there was a strong effect of the magnetic field as such.

4.2. Rhizoids of characean green algae

The Chara rhizoid is one of the most extensively studied plant cells in real microgravity. Experiments have been performed on board space shuttles (IML-2, SMM-05; Braun et al., 1996, 1999a, 1999b, 2002), during several sounding rocket flights (MAXUS and TEXUS; Buchen et al., 1991, 1993; Braun, 2002; Braun et al., 2002) and parabolic plane flights (Limbach et al., 2005), in several types of clinostats (classical, fast-rotating 2-D, 3-D clinostats), and in a RPM and a magnetic levitator of the HFML. The transparency and the relatively large size make this gravitropically tip-growing cell a suitable model system for research on plant gravity sensing and gravity-regulated growth responses (Limbach et al., 2005; Braun and Limbach, 2006; Braun, 2007; Hemmersbach and Braun, 2007). The apical actin cytoskeleton keeps the statoliths, membrane-bound vacuoles filled with BaSO4 crystals, in a dynamically stable position close to tip by precisely counteracting the apically directed force of gravity (Braun and Wasteneys, 2000; Braun et al., 2002). Upon tilting rhizoids, statoliths are displaced toward the physically lower cell flank, where they initiate the gravitropic bending of the cell tip back into the direction of gravity (positive gravitropism). Consequently, under the conditions of microgravity during TEXUS, MAXUS, or space shuttle flights, statoliths are rapidly displaced further away from the tip (Braun et al., 2002). After about 5 min, statoliths doubled their original distance from the cell tip.

To test whether magnetic levitation has a similar effect on statolith positioning as real microgravity, rhizoids were subjected to high-gradient magnetic fields (HGMF levitation) with different magnetic field strengths (7–29 T) and field-gradient products up to −4160 T2/m at the HFML Nijmegen. Optical components and mirrors were arranged and inserted in the bore of the magnet such that rhizoids growing vertically and horizontally in a small agar-filled plastic chamber (10×10×2 mm) could be observed within the different areas of magnetic field strength. The kinetics of the movements of statoliths in several rhizoids was video recorded and analyzed. Statoliths subjected to high-gradient magnetic fields did not show any significant displacement away from the cell tip. Even field-gradient products up to −4160 T2/m (at a magnetic field as high as 29 T) did not cause any measurable displacement of the statoliths away from the tip. In analogy with the results on the protists, also here due to the differences in densities and magnetic susceptibilities of the BaSO4 statoliths and the surrounding water, the levitation of the statoliths is expected to occur at higher values of the field-gradient product than the levitation point of water. Given the ρ and χ of BaSO4, levitation is expected at B×∂B/∂z=−6250 T2/m, which is currently feasible in 33 T Florida-Bitter and 45 T Hybrid magnets (which, however, have a smaller bore size, 32 mm). Besides the failure to provide a simulated microgravity environment, no significant impact of strong magnetic fields was detected on the cell's polar organization, integrity, and polarized growth.

In contrast to magnetic levitation, clinorotating rhizoids exhibited statolith displacement that was very similar to the one that was observed under the conditions of real microgravity (Cai et al., 1997; Braun et al., 2002; Limbach et al., 2005). Chara rhizoids were studied on classical 2-D clinostats at 2–10 rpm (Cai et al., 1997), a fast-rotating 2-D clinostat microscope at 60–90 rpm (DLR Cologne), a Japanese fast-rotating 3-D clinostat (Hoson et al., 1997), and a RPM (Dutch Space at DLR Cologne). Although clinorotation generally resulted in a clear basipetal displacement of statoliths, the statoliths' complex of rhizoids rotated on the classical clinostats often appeared more dispersed than on fast clinostats or in real microgravity. After clinorotation, more dispersed statoliths sedimented more slowly, which resulted in a delayed initiation of the gravitropic response. Obviously, rotation around two axes did not improve the quality of microgravity simulation but reduced the volume in which specimens experience a good-quality microgravity simulation from a cylindrically shaped volume to a spherically shaped volume of the same diameter of several millimeters depending on the rotational speed. The higher the rotational speed, the higher the residual g-force, ergo the smaller the useful sample volume (van Loon, 2007).

In rhizoids that were mounted in the center of the axes (±1 mm) of a RPM running in the 2-D mode at 60 rpm, statoliths also moved away from the tip, but in the real-random mode of the RPM (2–11 and 30–60 rpm) the effect was less pronounced; the statoliths moved more slowly and spread slightly more as compared to fast 2-D clinorotation and real microgravity. Growth rates of Chara rhizoids were not impaired by the clinostat and RPM treatment but rather appeared to be slightly increased in some cases.

Sample housing used for clinorotation and magnetic levitation of Chara rhizoids was generally simple, consisting mainly of an agar-filled chamber handmade of microscopic slides covered with long cover glasses and sealed on all sides with tape or of a macrolon chamber as was used extensively in the space shuttle and parabolic plane flights (Braun et al., 2002).

In conclusion, for investigations on the statolith-based gravity sensing system of Chara rhizoids, the 2-D fast-rotating clinostat represents an excellent simulator for microgravity, whereas the 3-D clinostat, the RPM, and the classical clinostat provide good simulators but are less suitable in the order listed. The high-gradient magnetic fields as applied in this study (magnetic levitation) failed to provide proper simulated microgravity conditions, but with the use of stronger magnets levitation of the statoliths in Chara rhizoids should be feasible.

4.3. Arabidopsis thaliana—cell growth and proliferation

Early studies on plant biology in space did not use a single biological model. The list of plant species used in space experiments until the first years of this century includes more than 30 members, among which wheat, lentil, and several Brassica species are the most repeated. However, in the last decades Arabidopsis thaliana has progressively become the most frequently used biological model in all kinds of studies on plant biology due to the advantages it offers in molecular biology, genetics, and developmental biology research. This species was the first plant whose genome was fully sequenced. Consequently, A. thaliana has also quickly emerged as the model of choice for space plant biology research.

An essential topic in this research field consists of discerning alterations in plant growth and development caused by the space environment and particularly by microgravity. This can be addressed by investigating cellular processes such as cell proliferation and growth that occur in meristematic tissues, where “meristematic competence” consists of the strict coupling between the proliferative state of the cell and its growing capability. In previous studies, carried out on the ISS, it was shown that the absence of gravity was capable of modifying cell growth and proliferation rates in the root meristem of seedlings after 4 days of growth. Similar disruption of this strict coupling was confirmed in a parallel experiment performed in a RPM by using the real random operation mode (Matía et al., 2010), demonstrating the success of this microgravity simulation method for experiments on Arabidopsis. Experiments were performed with similar experimental designs (seedlings growing on a wet paper containing Murashige and Skoog medium).

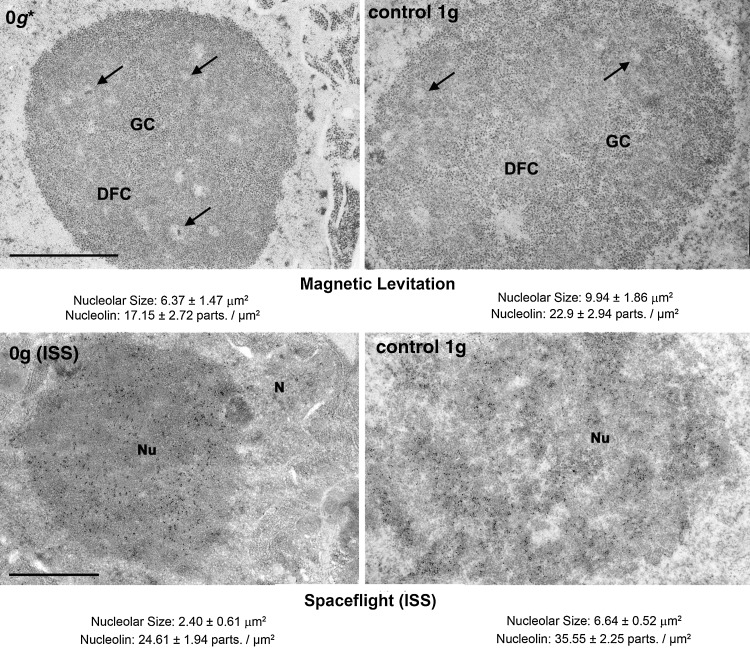

Additionally, within the frame of the joint ESA-GBF project, magnetic levitation has been used as a device for changing gravity conditions in plates/tubes in which seedlings were grown on agar-based medium. Interestingly, the physical effect of levitation was not visually observed in the roots of these seedlings, since root gravitropism was not abolished in the conditions of our experiment, owing to the fact that the starch-based organelles, the gravisensors of Arabidopsis roots, were not levitated in the 1400 T2/m magnetic field applied to the plants, although the intracellular water was levitated. However, under these conditions, intracellular water was unequivocally exposed to levitation conditions. Studies on the cell proliferation rate, nucleolar ultrastructure, and the levels of nucleolar proteins that were performed on samples grown in the 0g* position within the magnet (0g* at 16.5 T at the University of Nottingham facility, UK) confirmed the decoupling of cell proliferation and cell growth (Manzano et al., personal communication). Expression of the cyclin B1 gene, a marker of the G2/M transition in the cell cycle, evaluated by GUS staining on transgenic plants, decreased in 0g* despite the increase of the cell proliferation rate. All these parameters showed the same alteration with respect to the 1g control as in the RPM experiment and also, when applicable, as in the space-grown samples (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Ultrastructural images of the nucleolus of Arabidopsis root meristematic cells grown for 4 days under simulated microgravity in a magnetic levitation instrument (upper part) and under real microgravity in the ISS (lower part). Nucleolar parameters represent an accurate estimation of the rate of ribosome biogenesis and, consequently, of the level of protein synthesis and cell growth. The nucleolus is smaller in both real and simulated microgravity compared to the corresponding 1g controls. Furthermore, the levels of the nucleolar protein nucleolin, an essential factor for pre-rRNA synthesis and processing, estimated by ultrastructural immunogold procedure, were lower under both real and simulated microgravity than in the respective 1g ground controls. Bars indicate 1 μm in each experiment. Data taken from Matía et al. (2010) and Manzano et al. (personal communication). DFC, dense fibrillar component; GC, granular component; arrows indicate fibrillar centers. N, nucleus; Nu, nucleolus.

Hypergravity conditions have been tested for the first time for these parameters in both the HFML magnet, at the symmetrical position of 0g*, which produces 2g*, and the Large Diameter Centrifuge (LDC, ESA-ESTEC, Noordwijk, the Netherlands) used at 2g. The less evident observed alterations might indicate that the stress produced is weaker than that under real (ISS) or simulated microgravity (RPM or 0g*). Nevertheless, a decoupling between cell growth and proliferation was also detected, however, in an opposite sense to that one observed in microgravity (Manzano et al., 2012b).

On the RPM, as well as under the influence of the high magnetic field (all positions within the magnet, including internal 1g* control), an inhibition of the auxin polar transport was observed in agreement with results previously obtained in spaceflight (Ueda et al., 1999). This was visualized in the root of transgenic seedlings by the staining pattern of DR5-GUS, an artificial auxin responsive promoter coupled to a reporter gene. However, hypergravity per se (LDC, 2g) did not alter the auxin polar transport.

In addition to the work carried out with seedlings, solid in vitro cell cultures of Arabidopsis thaliana were used and exposed to the HFML magnet (maximum field of 16.5 T from 0g* to 2g*), the RPM (real random mode), and the LDC (2g, hypergravity), as a homogeneous proliferating cellular material with the use of agar-filled tubes/plates of the required size (Manzano et al., 2012a). This material has been rarely used in real spaceflight experiments (Paul et al., 2012), but its use as source material for altered gravity research has the purpose of testing whether cells not specialized in gravity perception respond to gravity alteration. Such systems allow for the use of molecular techniques that demand a large biomass of proliferating cells, which is difficult to collect from seedlings. Therefore, the objectives of using GBFs with this material, apart from the facility validation by comparison with space experiments, included the preparation for the use of plant cell cultures in space, the comparison of the alterations observed in cellular parameters in cell cultures with the results obtained on seedlings, and the extension of the analysis to new parameters provided by high-throughput genomics and proteomics methods. Other laboratories are also involved in the use of these plant biological materials in altered gravity research, with application to other cellular and molecular processes (Martzivanou et al., 2006; Barjaktarovic et al., 2009).

With the use of Agilent microarray-based technology to detect global genome gene expression profiles, the results from the RPM and the magnet were compared with Affymetrix microarray-based expression data obtained in real microgravity (Paul et al., 2012). Although the gene ontologies affected are similar in all experiments (mainly stress-related genes), the intensity of the gene expression changes and the particular collection of genes affected are strongly dependent on the source material (seedlings, diffuse callus, confluent callus) and the duration of the treatment.

Specifically, in the magnet experiment analyzed with genomic and proteomic methods, the effects of altered gravity were significantly masked by other magnetic field effects. In fact, the intensity of alterations caused by the gravitational stress was strengthened by an amplified environmental stress caused by the synergy between the altered gravity and the high magnetic field, both at the gene expression and proteomic level (Manzano et al., 2012a; Herranz et al., 2013).

In general, data obtained from cell cultures reveal alterations in cell growth and proliferation that could be compared to those found in seedlings, indicating that a significant part of the response to altered gravity does not depend on specialized cells containing mechanoreceptors (Manzano et al., 2012a; Herranz et al., 2013). In cell cultures we verified (i) the alteration of the relative proportion of cell cycle phases (which probably leads to a change in the duration of the cycle), (ii) the change in expression of numerous genes acting as regulators in cell cycle checkpoints of phase transitions, and (iii) the deregulation of ribosome biogenesis by means of the alteration of nucleolar structure and of transcriptional and post-translational changes of key proteins of this process, such as nucleolin and fibrillarin.

More recently, we used the pipette clinostat (Fig. 1B) for exposing suspension plant cell cultures to fast clinorotation (60 rpm). Experiments have been done in which both asynchronous and synchronized samples were used to gain knowledge on the effects of clinorotation on cell cycle regulation and progression. Preliminary results of these experiments suggest that the cell cycle duration was altered under 2-D clinorotation, although in this experiment the 1g control was performed in the same container, without shaking, but otherwise with the same experimental setup (1 ml pipette) also reflected high differences in proliferation rates. This indicates that the configuration of the 1g control experiments has to be carefully considered.

We conclude that, for Arabidopsis seedlings and cell cultures especially, magnetic levitation presents problems for use as a method of microgravity simulation, as it is necessary to separate the effects of altered effective gravity from other effects of the strong magnetic field, which can be challenging. The problem is more apparent in cell cultures and molecular biology methods than in seedlings and cell biology techniques (i.e., ultrastructural analyses). So far, the results with respect to Arabidopsis on the RPM are totally homologous to those obtained in real microgravity. Specifically for cell cultures, it is mandatory to expose experimental and control samples to the same environment, including temperature, shaking, and magnetic and inertial forces, parameters often difficult to control in GBFs.

4.4. Drosophila behavior and gene expression

Drosophila is used extensively as a model animal system in space research due to its small size, short life cycle, and the wealth of genetic literature support. Additionally, their life-support requirements are relatively undemanding, requiring little or no human intervention once in orbit. As part of this GBF comparison project, we have studied the behavioral response of the flies to simulated microgravity conditions and the effect of simulated microgravity on the gene expression profile.

The behavioral changes of the flies in microgravity conditions have been studied previously in experiments on board the space shuttle Columbia, STS-65 IML-2 mission (Benguria et al., 1996) and later as part of the Cervantes mission to the ISS (de Juan et al., 2007). Video recordings of the flies in space were analyzed and compared with recordings made of flies on the ground. The analysis showed that, in containers small enough to prevent flight, flies move more often and walk longer distances in microgravity compared to flies in 1g. Since it was not possible to implement a 1g control for behavioral comparisons on board these particular spaceflight missions, all the influences of microgravity on behavior were identified by comparison with a 1g control experiment implemented on the ground. Therefore, we cannot be certain that the behavior of the flies in space was sensitive to the spaceflight preparations made immediately before launch, introducing some doubt about the root cause of the anomalous behavior observed in space.

To address these uncertainties, we performed experiments using ground-based devices for hypergravity and simulations of microgravity; the LDC (2g), RPM (real random mode at DESC-ESTEC), and magnetic levitation in a superconducting magnet at the University of Nottingham (Hill et al., 2012) were used to clarify the contribution of gravity to motility and the aging processes.

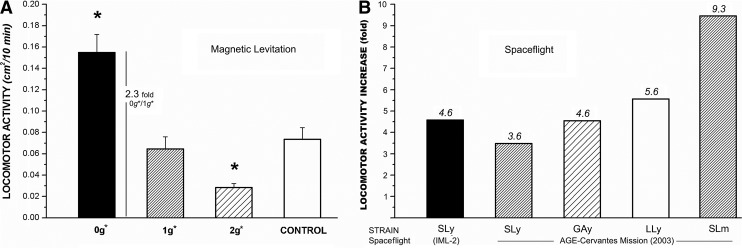

In experiments in which magnetic levitation was used, the walking paths of flies confined to a 25 mm diameter, 10 mm tall cylindrical “arena” enclosing the stable levitation point of water (0g*) were analyzed. Within this arena, the flies experienced pseudo-weightless conditions. Flies were observed levitating within a few millimeters of the empirically determined levitation point of water (Herranz et al., 2012; Hill et al., 2012). Two additional groups of flies were exposed to pseudo-hypergravity conditions (in an arena enclosing the 2g* point) and normal gravity conditions (arena enclosing the 1g* point) within the spatially varying field, and a fourth arena was set up well away from the magnet (1g). The behavior of flies in the 0g* arena was found to be consistent with that of flies flown on the space shuttle Columbia and the subsequent mission to the ISS; a pronounced increase in the frequency of locomotor activity and the walking speed of the flies was observed in the pseudo-weightless conditions of levitation, compared to flies in the 1g* and 1g arenas (Hill et al., 2012). Flies moved more slowly in the 2g* arena compared to flies in the 1g* and 1g arenas. Comparison of flies in the 1g* arena with flies in the 1g arena revealed no additional effects of the strong magnetic field on behavior, up to 16.5 T. All the experiments in the magnet and the 1g control located away from the magnet were performed simultaneously, under the same conditions of atmospheric pressure, temperature, humidity, lighting, and with the same batch of flies (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Comparison in the motility of flies exposed to simulated and real microgravity. (A) Motility in the magnet (simulated microgravity and hypergravity) expressed as global activity in cm2/10 min. Activity is almost 3× in unloaded conditions and 0.5× in 2g* simulation. Average activity of 20 periods of 0.5 min is indicated with the bars (statistical significance *p<0.05 has been calculated with the Bonferroni–multiple ANOVA method). (B) Magnetic levitation data (Hill et al., 2012) shows the same trend as real spaceflight mission data obtained from the IML2 shuttle (Benguria et al., 1996) and the AGEing Cervantes mission (de Juan et al., 2007) experiments as resumed in part (B); motility increased from 3 to 9 times under real microgravity conditions depending on Drosophila selected strains exposed [SL, short life strain, comparable to wild type; GA, altered gravity strain; LL, long life strains; y, young (<2-week-old imagoes); m, mature].

Similar effects have been observed in the RPM/LDC facilities, in which flies were constrained to move within a Biorack Type-I container, of the type employed on board the ISS. In this case, however, mechanical forces and vibration produced during the sudden changes in rotation and speed linked to the real random mode disturb Drosophila behavior similarly to the effect detected in paramecia, making a video-based analysis of the walking behavior impossible.

The RPM/LDC experiments showed that the influence of microgravity on the motility of imagoes varied between different Drosophila strains. Furthermore, for a particular strain, the influence of microgravity was found to be dependent on the age and gender of the flies and closely related with environmental conditions (Serrano et al., 2010; Serrano et al., 2012). Consequently, not only the facility and environmental condition but also the biological state (i.e., age, gender, strain) of the organisms should be carefully considered in the experiment design.

The global gene expression profile has been observed to be affected in space, but different studies have found diverse intensity effects, from being nearly insignificant to affecting thousands of genes. Our own real microgravity data belong to the latter case, suggesting a major disturbance of the global gene expression profile during Drosophila metamorphosis in microgravity as detected by microarray analyses (Herranz et al., 2010). Our expectation is that these differences rely on different suboptimal environmental conditions under previous space experiments.

Experiments on the response of the transcriptome have been performed in different GBFs: real random RPM, levitation in a superconducting magnet (0g*), and hypergravity in the LDC and in the magnet (2g and 2g*), replicating previous experiments in real microgravity (ISS) (Herranz et al., 2010, 2012). The analysis indicated firstly that the RPM real random mode produces a very similar gene expression profile to the one obtained in microgravity; 90% of genes found altered in RPM experiments are also observed in ISS samples. Secondly, 10g hypergravity produces a less intense and opposite effect; similar genes are altered in 10g hypergravity, but the genes that are up-regulated in simulated microgravity are down-regulated in hypergravity and vice versa. Thirdly, the most profound effects were very closely related to suboptimal environmental conditions (Herranz et al., 2010). In the case of magnetic levitation, although some global-scale effects were found, the 1g* control (samples exposed to 16.5 Tesla but without field gradient) also showed many of these effects, making it challenging to isolate the microgravity effects from “simulation side effects” (Herranz et al., 2012), that is, other effects of the strong magnetic field besides that of levitation.

Our investigations included analysis of the impact of population-related and environmental factors such as temperature, oxygen concentration, and magnetic field; many of the environmental factors studied are related to confinement imposed by the Biorack Type I container conditions (Herranz et al., 2007, 2009). The pooled analysis of all gene expression experiments suggested a synergic effect of environmental factors in the microgravity response. The response to microgravity is not consistent but depends strongly on the original state of the organism and relates to stress responses, in particular a mixture of biotic, abiotic, and defense responses. We speculate that an explanation for this finding might have an evolutionary background; organisms have evolved groups of genes and stress pathways to control the adaptation to multiple stresses they have encountered temporarily during their evolution. Gravity has remained constant on Earth since life appeared on our planet, but microgravity has never been experienced and, thus, a specific response could not have evolved.

We conclude that, for Drosophila gene expression arrays, the RPM is a good simulator for real microgravity, as it revealed very similar results. In the experiments in which magnetic levitation was used, effects of the strong magnetic field besides that of levitation were observed, making it challenging to identify the effects of simulated microgravity. For behavioral studies (fast detection of the g-vector), on the other hand, the RPM offers a relatively good simulation method (similar effect of increased motility was observed); but in this case, we suggest that magnetic levitation should be used preferentially since the magnet allows the behavioral effect of microgravity on the flies to be observed, unaffected by the random inertial movements induced by the RPM.

4.5. Fish behavior

Fishes are ideal model organisms to investigate the performance of the vertebrate vestibular system in correlation with features of the inner ear (especially of the ear stones, the otoliths), as these structures are highly conserved among all vertebrates. Concerning the vestibular fitness in different gravitational environments, the observation of specific aberrant behavioral responses (i.e., kinetoses such as spinning movements and looping responses) is an excellent method.

Experiments in which a RWV was used and drop-tower experiments at various g-levels were carried out on larval cichlid fish Oreochromic mossambicus and zebrafish Danio rerio. The animals did not show any altered behavior on the RWV, such as aberrant spinning movements and looping responses. At high speeds, they were centrifuged away; at lower speeds, the fish behaved completely normally. In the drop-tower experiments, at first, the stationary platform of the drop-tower capsule (10−6g) was used, and subsequently, a centrifuge within the drop capsule was employed to achieve a series of 10 distinct levels of reduced gravity. Under 10−6g, five types of behavior were observed: normal swimming, normal resting, kinetotic behavior (namely spinning movements), looping responses, and zigzag movements.

Experiments designed to deprive fish of the gravity stimulus with a RPM (Dutch Space) and magnetic levitation were not carried out for the following reasons. The maximum velocity of the RPM (20 rpm) was not sufficient to yield a disorientation of animals that remained in the center of an approximately 8×4×4 cm cubic chamber. We intend to use a modified RPM with 60 rpm in a future experiment. Regarding magnetic levitation, the number of animals needed for statistical analyses could not be accommodated in the holding chamber for technical reasons.

Most animals that display spinning behavior under 10−6g had highly asymmetric utricular otoliths as compared with normally behaving individuals, and the ratio of animals swimming kinetotically increased with decreasing environmental gravity.

We also found a clear correlation between otolith asymmetry and the level of gravity that induced spinning movements: the higher the otolith asymmetry, the higher was the threshold of gravity-inducing kinetosis, for example, 3.48% otolith asymmetry in animals spinning at 0.3g and 1.12% at 0.015g. Comparative analyses in which zebrafish were used were not carried out, as we wanted first to get a picture as thorough as possible of the cichlids' behavior and associated issues at altered gravity.

We conclude that the RWV is not suited for behavioral studies on fish, as free swimming late-larval stages are not affected by a rotation at low speed. At high speeds, the RWV acts like a centrifuge. Moreover, the RPM used in this study is also not suitable for behavioral studies as long as the speed of rotation is too low to disorient the animals. The drop-tower is a fine instrument that provides real microgravity for the analysis of behavior at “high quality microgravity” (10−6g) and at distinct g-levels below 1g (centrifuge active).

4.6. Fish otolith gravisensing

Studies in which zebrafish were used were carried out by Chinese colleagues in close cooperation with us, who used a RWV (Li et al., 2011). As discussed above concerning studies on behavior, the maximum speed of the RPM used (20 rpm) is not regarded as sufficient to provide stimulus deprivation in fish. It is therefore to be expected that otolith growth will not be affected by RPM treatment.

Regarding magnetic levitation (HFML, Nijmegen, the Netherlands), it is well known from previous studies under hypergravity that several days of altered gravity are required to yield statistically relevant effects on otolith growth. For technical reasons, runs that last days cannot be executed with this Bitter magnet but are possible with the use of a superconducting magnet, such as the ones used for levitation experiments at the University of Nottingham, UK. Hence, only experimental results from the RWV (designed and constructed at DLR) were compared with real microgravity data.

In the course of an earlier space experiment, late-larval cichlids (vestibular system operational) were subjected to microgravity during the FOTON-M3 spaceflight mission. Animals of another batch were subsequently clinorotated in a submersed fast-rotating clinostat with one axis of rotation (2-D clinostat, 60 rpm; designed and constructed at DLR). After the experiments, animals had reached a free-swimming stage.

Animals that were grown under spaceflight conditions exhibited significantly larger than normal otoliths (both lapilli and sagittae, involved in sensing gravity and the hearing process, respectively). Clinorotation resulted in larger than 1g sagittae. However, no effect on lapilli was obtained. Earlier studies had shown that clinorotation resulted in larger than 1g otoliths when early-staged animals are used or when clinorotation covers a comparably brief period of development of late-staged cichlids (Li et al., 2011). Interestingly, wall vessel rotation yielded larger than normal otoliths in early-staged zebrafish Danio rerio, but otoliths of cichlid fish were not affected.

We conclude that an RPM, as it has been available (Dutch Space), is of no use concerning developmental studies, as long as the speed of rotation is too low to disorient the animals. It may be used, however, with very early larval stages (respective experiments have not been undertaken yet). We also conclude that a RWV only can be used regarding analyses on otolith growth/developmental issues when animals have not yet reached a stage when they can swim freely. It also depends on the species (mouth-breeding like the cichlid versus egg-laying like the zebrafish) whether a RWV is able to provide a good simulation of microgravity. Extreme care has to be taken when considering the use of a RWV. A 2-D clinostat is well suited for carrying out experiments on developing fish (all stages). Yet it is not fully understood under which circumstances (developmental stage of animals, developmental period analyzed) clinorotation causes similar effects as real microgravity in spaceflights.

4.7. Mammalian cell cultures (adherent)

During previous studies in real microgravity, it was found that epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced signal transduction is sensitive to microgravity. Studies during sounding rocket missions (real microgravity) demonstrated that EGF-induced early gene expression of c-fos and c-jun was decreased under microgravity conditions. Moreover, cells showed increased cell rounding under microgravity conditions. Cell rounding is largely determined by the actin filament system. The relative F-actin content was shown to increase during microgravity conditions. Therefore, it can be said that real microgravity changes gene expression and cell morphology in A431 cells (de Groot et al., 1991; Rijken et al., 1991; Boonstra, 1999).

The EGF-induced early gene expression and cell morphology changes were also studied on the fast rotating 2-D clinostat (CCM, Nuenen, the Netherlands) at 60 rpm, and similar results were obtained under simulated microgravity conditions as compared to real microgravity (Boonstra, 1999). Similar observations were also done with cells in suspension, such as lymphocytes (Cogoli, 1992). This rounding of A431 cells was further studied in simulated microgravity with an RPM, used at random speed, random direction, and random interval. The maximum random speed was set as 360°s−1. It has been demonstrated that exposure of the cells in the RPM resulted in a transient process of cell rounding and subsequent reattachment and flattening of the cells. The cell rounding was accompanied by an increased cortical actin cytoskeleton, decreased actin stress fibers, and disappearance of focal adhesions (Moes et al., 2010). Similar results were also obtained in non-transformed mouse fibroblasts. Magnetic levitation induced similar changes in the actin morphology of A431 cells and mouse fibroblast that were also described in real microgravity. A transient process of cell rounding and renewed spreading was observed in time, illustrated by a changing actin cytoskeleton and variation in the presence of focal adhesions. However, further experiments demonstrated that the magnetic fields may induce similar changes in actin morphology under 1g conditions. Therefore, it is required to confirm that responses are induced by the simulation of microgravity and not caused by magnetic field side effects. Exposure of mouse fibroblasts C3H10T1/2 to magnetic fields with or without levitation was shown to result in similar cytoskeletal changes. This indicates that the use of magnetic levitation for microgravity simulation may not be a suitable method to study gravisensing of mammalian cells. However, quantitative measurements of cytoskeletal polymers need to be done to fully understand the impact of the magnetic field per se and of simulated microgravity and their effect on the cytoskeleton.

We conclude that both the fast rotating clinostat and the RPM are valuable tools for simulating microgravity conditions in adherent mammalian cells. In contrast, the magnetic field used for levitation has significant effects in these cells, especially on the cytoskeleton; therefore, magnetic levitation is not applicable to simulate microgravity in these adherent cells.

4.8. Mammalian cell cultures (suspension)

Expression of the cell cycle regulatory protein p21Waf1/Cip1 in human Jurkat T cells and phagocytosis and oxidative burst reaction in rat N8383 macrophages were used as a model system for non-adherent/semi-adherent cells. After treatment of Jurkat T cells with PMA, p21Waf1/Cip1 protein expression was reduced 4.2-fold after 15 min in 1g but was enhanced 1.6-fold after 15 min during clinorotation (2-D test-tube clinostat, 60 rpm, pipette inner radius 1.5 mm, maximal residual acceleration 6×10−3g, 37°C) (Thiel et al., 2012). In addition to the protein expression, mRNA transcription levels were analyzed by real-time PCR. After 2 h of clinorotation, p21Waf1/Cip1 mRNA was decreased, whereas we detected increased levels after 2 h under magnetic levitation at 0g* position (HFML, Nijmegen, the Netherlands). In general, we observed severely degraded RNA in all magnetic levitation experiments in which Jurkat T cells were used. Primary CD4-T cells from human donors did not survive the magnetic levitation experiment but were viable before transfer into the magnet. Phagocytosis-mediated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by N8383 cells was reduced by clinorotation, while no significant influence of clinorotation on the vitality of the cells was detected. A reduction in ROS was also observed in real microgravity during parabolic flights. Interestingly, the amount of reduction in ROS was directly influenced by the speed of clinorotation. This result clearly shows that comparative studies by changing the speed of the clinostat are necessary to provide similar conditions as in microgravity. According to the clinostat experiments, endpoint measurements were performed also in the magnetic levitation setup. No significant influence of magnetic levitation on phagocytotic activity or ROS production could be detected.

Therefore, we conclude that the fast rotating clinostat is a valuable tool to simulate microgravity for suspension cell cultures. In contrast, the magnetic levitation setup as used in this study failed to reproduce the results obtained by clinorotation and from real microgravity conditions.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

To anticipate which simulator might be the most appropriate GBF for a given biological system to provide a good simulation of microgravity, the following table summarizes the findings of the ESA GBF project. Table 1 could serve as a guide for scientists preparing space experiments or who wish to do stand-alone experiments under altered gravity conditions. The quality of microgravity simulation strongly depends on numerous factors, such as sample size, type of tissue and cells, and so on, which are discussed in this paper, as well as the reaction time and the threshold of gravity sensing of the biological process studied.

Table 1.

Biological Responses in Microgravity Simulators (GBFs) in Comparison to Real Microgravity

| Object | 2-D Clinostat | RPM | Levitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paramecium | ++ | − | − |

| Euglena | ++ | − | − |

| Chara | ++ | + | −* |

| Arabidopsis | |||

| • Cell proliferation/growth | n.a. | ++ | +* |

| • Gene expression | n.a. | + | − |

| Drosophila | |||

| • Behavior | n.a. | + | ++ |

| • Gene expression | n.a. | ++ | + |

| Fish | |||

| • Behavior | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| • Development | + | n.a. | n.a. |

| Mammalian | |||

| • Adherent cells | + | + | − |

| • Cells in suspension | + | n.a. | − |

For further details see corresponding sections.

Symbols indicate that biological response to simulation is identical (++), similar (+), or different (−) to those of real microgravity experiments. n.a. means not applicable or data not available from spaceflights.

With the available field-gradient, levitation of statoliths was not achieved.

Table 1 reveals that the 2-D clinostat especially running in the fast rotating mode provides a good simulation of microgravity and can be recommended for most biological organisms studied. The RPM was also found to be a suitable simulator for some larger organisms as was shown for Drosophila and Arabidopsis. In studies of Drosophila behavior, magnetic levitation was particularly successful at reproducing the effects of real microgravity and obtained better results than the RPM. In the other studies, magnetic levitation was found to be of limited use as a microgravity simulator, owing to the difficulty in separating the effects of levitation from other effects of the strong magnetic field on the organism.

The fast-rotating clinostat and the RPM are based on the principle of changing the direction of gravity with respect to the sample mounted in the rotation axis. If the biological sensing process is slow enough, the system will no longer respond to the omnilateral stimulation. However, if the sensing process is fast and sensitive, the system might be continuously mechanically stimulated and might respond with typical stress reactions or even cell death (van Loon, 2007). Randomization of the gravity vector requires time; therefore, only processes that require a certain lag-time phase can be studied. Since the randomization time is dependent on the rotational speed, different processes require different rotational speeds, depending on their intrinsic lag-time phase. For this reason, clinostats or RPMs cannot properly simulate microgravity for relatively fast molecular and cellular processes. Increasing the speed of rotation strongly increases the quality of the simulated microgravity and can even provide near weightlessness (Briegleb, 1992). However, fast rotation also strongly reduces the area along the rotation axis in which the omnilateral stimulation prevents effectively gravity sensing. Further away from the rotation axis, centrifugal forces dominate over the randomization effect. Therefore, fast clinorotation provides simulated near weightlessness for only small samples that are positioned along the rotation axis. For RPM experiments in which a relatively large liquid volume is used, one should note liquid movement and shear forces within the volume (Leguy et al., 2011). The current study confirms that the RPM seems to be the system of choice for Arabidopsis (Hoson et al., 1992, 1997; Kraft et al., 2000).

We considered magnetic levitation to be an interesting new technology for microgravity simulation with which to overcome problems such as lag phase of perception due to its molecular scale effects and continuous (not time-averaged like in the case of clinostat or RPM) presence of the magnetic field gradient (Beaugnon and Tournier, 1991a, 1991b). Consequently, no lag-time phase is required, and organism response time to microgravity is not an issue under magnetic levitation. Results of our studies on Drosophila melanogaster (Hill et al., 2012), in which the effect of real microgravity on the behavior of flies was successfully reproduced by levitation, suggest that levitation may be suited to study behavioral responses to microgravity in small animals; further studies on other organisms are required to assess this possibility. Our other studies in which levitation was used showed limitations of this technique for investigating wider effects of microgravity on the organism and the need of further investigations on the effects of strong magnetic fields on biological systems.

These considerations clearly show that the experimenter has to carefully balance and consider the different aspects of the various microgravity simulators and operation modes. Based on the results of this study, it is recommended that several GBFs and different modes of operation are used before any conclusions are drawn.

Experimental design, a detailed technical description of the operational modes for the GBFs, and the hardware used for the exposure of the biological systems should always be thoroughly described in the methods section of publications. The physical parameters associated with each of the different experimental approaches might induce direct or indirect effects on the system (Briegleb, 1992; Klaus, 2001) and should be considered. This information is meant to help future investigators find the appropriate mode of operation for their system. Space experiments carried out under conditions of real microgravity still represent the ultimate validation for the suitability of the simulation approach on ground.

Acknowledgments

The primary idea of performing such a multi-GBF multi-organism comparison was proposed by the late Professor Roberto Marco, to whom this paper is affectionately dedicated. The joint effort to compare our results has been funded by the ESA Access to Ground Based Facilities SEGMGSPE_Ph1 Project “Systematic Evaluation of the ground based (micro-) gravity simulation paradigms available in Europe. First Phase: Similarities and Differences between the different approaches (ESA contract 4200022650).” Nevertheless, primary research reviewed in this manuscript has been possible by grants from the Spanish Space Program in the “Plan Nacional de Investigacion Cientifica y Desarrollo Tecnologico” AYA2009-07792-E to R.H., AYA2009-07952 and AYA2010-11834-E to F.J.M., German Space Administration grants on behalf of Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie 50WB0527 to R.H., 50WB0815 to M.B., 50WB0828 to M.L., 50WB0921 to O.U., and Dutch Space Research Organization NWO-ALW-SRON grant MG-057 to J.J.W.A.vL. Magnetic levitation at the High Field Magnet Laboratory in Nijmegen was granted by EuroMagNET II under the EU contract n° 228043 and by the Stichting voor Fundamenteel Onderzoek der Materie (FOM), financially supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO). Research using the University of Nottingham's superconducting magnet was supported by grants from the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), Nos. GR/S83005/01 and EP/G037647/1. R.J.A.H acknowledges EPSRC for support under a Research Fellowship EP/I004599/1 and C-DIP grant EP/J005452/1.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Abbreviations

2-D, two-dimensional; 3-D, three-dimensional; DLR, German Aerospace Center; EGF, epidermal growth factor; GBF, ground-based facility; HFML, High Field Magnet Laboratory; ISS, International Space Station; LDC, Large Diameter Centrifuge; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RPM, random positioning machine; RWV, rotating wall vessel.

References

- Albrecht-Buehler G. Possible mechanisms of indirect gravity sensing by cells. ASGSB Bull. 1991;4:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht-Buehler G. The simulation of microgravity conditions on the ground. ASGSB Bull. 1992;5:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anken R. Baur U. Hilbig R. Clinorotation increases the growth of utricular otoliths of developing cichlid fish. Microgravity Sci Technol. 2010;22:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Babbick M. Dijkstra C. Larkin O.J. Anthony P. Davey M.R. Power J.B. Lowe K.C. Cogoli-Greuter M. Hampp R. Expression of transcription factors after short-term exposure of Arabidopsis thaliana cell cultures to hypergravity and simulated microgravity (2-D/3-D clinorotation, magnetic levitation) Adv Space Res. 2007;39:1182–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Barjaktarovic Z. Schutz W. Madlung J. Fladerer C. Nordheim A. Hampp R. Changes in the effective gravitational field strength affect the state of phosphorylation of stress-related proteins in callus cultures of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:779–789. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaugnon E. Tournier R. Levitation of organic materials. Nature. 1991a;349:470. [Google Scholar]

- Beaugnon E. Tournier R. Levitation of water and organic substances in high static magnetic fields. Journal de Physique III. 1991b;1:1423–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Benguria A. Grande E. de Juan E. Ugalde C. Miquel J. Garesse R. Marco R. Microgravity effects on Drosophila melanogaster behavior and aging. Implications of the IML-2 experiment. J Biotechnol. 1996;47:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(96)01407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M.V. Geim A.K. Of flying frogs and levitrons. European Journal of Physics. 1997;18:307–313. [Google Scholar]