Abstract

The evaluation of patients at risk for limb loss secondary to peripheral arterial disease begins with a complete history and physical exam, and noninvasive studies in the vascular lab, including duplex ultrasonography. However, successful revascularization depends on high-quality, accurate imaging of the lower extremity vasculature. The traditional gold standard for vascular imaging, digital subtraction angiography, has been improved upon as technologic advances have enabled high-quality alternatives for preoperative (i.e., computed tomography [CT] angiography and magnetic resonance angiography [MRA]) and intraoperative imaging (i.e., intravascular ultrasound [IVUS], cone beam CT, and CO2 angiography). Here we describe these advanced invasive and noninvasive imaging alternatives and their utility in limb salvage procedures.

Keywords: Imaging, Peripheral Artery Disease, Limb Salvage

Introduction

Patients with suspected peripheral arterial disease (PAD) who present with critical limb ischemia (CLI) require intervention for limb salvage. The evaluation process begins with a complete history and physical exam and noninvasive studies. Successful revascularization depends on high-quality, accurate imaging of the lower extremity vasculature. Recent advances in imaging technology have significantly influenced the preoperative evaluation of patients with PAD. The following describes both noninvasive and invasive alternatives to obtaining high-quality images in limb salvage patients.

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) has long been the de facto gold standard for evaluation of atherosclerotic lesions in individuals with PAD. However, DSA is limited by the fact that it creates a two-dimensional (2D) image of a three-dimensional (3D) structure, meaning that the image is dependent on the angle at which it is acquired and the projection of the vessel of interest (Figure 1). In one study that compared pre-amputation angiograms to pathologic specimens in patients who required amputation within 180 days (mean 53 days post angiogram), angiography significantly underestimated severity of stenosis, concentricity of plaque, and calcification grade, even in “normal” appearing vessels.1 Additionally, eccentric plaques do not consistently correlate with reduction in luminal cross-sectional area, an important influence on hemodynamic effects. Indeed, Schoenhagen and colleagues have shown that intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) can demonstrate how early plaque undergoes “positive” remodeling, meaning that as plaque grows, the arterial wall expands outward.2 As such, lesions present only with mild irregularities at the outset, despite a potentially large plaque burden. Thanks to important advances in imaging technology, there are now several advanced imaging techniques that allow for comprehensive preoperative and intraoperative evaluation of PAD patients for limb salvage.

Figure 1.

Imaging by (A) CTA, (B) DSA, and (C) IVUS of a patient with diffuse occlusive disease and a patent endovascular aortic repair. CTA: CT angiography; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound

One of the most impactful changes in angiographic imaging technology has been the replacement of traditional mobile C-arms, which are inadequate to perform many of the endovascular interventions that are performed routinely. Modern fixed imaging systems have enough mobility to fully evaluate the patient from head to toe; they also have positional memory and easy maneuverability that improve work flow, decrease operative times, and produce extremely high-quality images.

Image quality has been further improved by replacing traditional image intensifiers with flat panel detectors,3 which offer higher dynamic range, dose reduction, fast digital readout, and the possibility for dynamic acquisitions of image series.4 While these images share common pitfalls with traditional DSA acquisitions from mobile C-arms, the quality is vastly superior.

Noninvasive Imaging Modalities

Ultrasound and Noninvasive Studies

The initial clinic visit of any patient with PAD includes not only a thorough history and physical exam but also a visit to the vascular laboratory. Prior to angiographic imaging, patients should undergo arterial and venous duplex imaging in addition to other noninvasive studies (i.e., segmental pressures, ankle and toe brachial index evaluation). While they do not provide sufficient detail for complete operative planning, these relatively inexpensive studies can help localize and quantify disease and provide baseline numbers. Ultrasound is also an excellent option for surveillance of lower extremity bypasses, as it has been shown, in the early post-operative period, to be predictive of patency.5

CTA

Noninvasive 3D imaging is the technique of choice when evaluating patients for limb salvage procedures and can serve as a useful adjunct for surveillance when duplex ultrasound provides inadequate information. Following several important developments in CT technology, CT angiography (CTA) has become the preferred technique for most vascular surgeons. Prior to the introduction of multidetector technology, CT was limited to the assessment of a single vascular bed — clearly an inadequate study for a patient with PAD. Four-detector row CT enabled imaging of the entire lower extremity vasculature with a single contrast bolus, and 16-slice followed by 64-slice scanners served to perfect spatial resolution. Advances in both hardware and software have resulted in decreased acquisition times while improving image quality by decreasing motion artifact and enhancing resolution.

Currently, there is wide availability of multidetector (16D and increasingly 64D) spiral CT scanners that can obtain continuous linear images over 360° with the option of obtaining slice thickness of less than 1 mm.6, 7 Furthermore, these images can be reconstructed into additional 2D and 3D data sets through standardized post-processing techniques (Figure 1A). Axial images of the peripheral arteries are difficult to interpret. Through post-processing, maximum-intensity projections (MIPs) based on the optimal projection for each vascular bed are created, and whole-volume MIPs are created to allow for 3D viewing of the arteries with soft tissue, bone, and (if necessary) calcifications subtracted. While these images should be compared to original axial cuts for verification,8 they serve as an important guide for interventional planning.

In a 2009 meta-analysis of multidetector CTA for the evaluation of PAD, the sensitivity of CTA for detecting more than 50% stenosis or occlusion was 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 92–97%), and specificity was 96% (95% CI, 93–97%). CTA correctly identified occlusions in 94% of segments, the presence of more than 50% stenosis in 87% of segments, and absence of significant stenosis in 96% of segments.9 Of note, the majority of studies comparing CTA to DSA are in patients with claudication (68%), and not CLI. In these patients with greater disease burden, whose contrast transit may be altered, studies have yet to definitively determine the impact on image quality for CTA.

MRA

Much like CTA, technologic advances in magnetic resonance (MR) imaging have made heretofore unreliable angiographic imaging an appealing option. Traditional 2D time-of-flight (TOF) MRA employed black-blood imaging sequences to assess the vessel wall and bright-blood sequences as a correlate to angiography. These sequences are based on the spin echo of protons in the blood flowing into the vessel; they can be electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated, which reduces motion artifact, and supply useful information about vessel wall anatomy. However, MRA sequences are flow-sensitive acquisition methods that suffer from long acquisition times and overestimation of vessel stenosis in smaller peripheral vessels, making it an imperfect tool for evaluating PAD.10 This fact has played a significant role in the prejudice against MRI as a reliable modality for PAD evaluation. Current advances in MR, such as development of novel MR sequences, higher magnetic field strength, and improved scanner hardware, software, and coil technologies have led to significantly improved image quality and acquisition times.11 Furthermore, the addition of contrast-enhanced (CE) sequences have vastly improved vascular imaging capability in MR. Gadolinium-based contrast agents have properties that lead to significant reduction in T1 relaxation times, allowing for delineation of the vessel from the surrounding structures when contrast-enhanced images are subtracted from pre-contrast images (Figure 2). These sequences have not yet been standardized, but most include 2D ECG-gated pre-contrast sequences and 3D CE sequences acquired with multiple bolus/station or bolus-chase/moving table techniques.7

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of proximal anastomosis in a patient with ilioperoneal bypass.

In the early 1990s, studies comparing 2D TOF MRA to DSA yielded promising results, with reported sensitivities ranging from 86–97% and specificities of 88–99% for identifying less than 50% stenosis in patients with symptomatic PAD.12-14 These studies demonstrated the feasibility of MRA for identifying patients with significant stenosis. A 2000 meta-analysis of both 2D and 3D CE-MRA found that 3D techniques improved diagnostic performance (relative diagnostic odds ratio: 7.46 compared to 2D).15

MRA can be a highly useful alternative to CTA despite certain drawbacks, most importantly cost and availability of the technology as well as expertise necessary to perform and interpret these exams. Although initial excitement for its use in patients with renal insufficiency has waned following the observation of nephrogenic systemic sclerosis secondary to gadolinium use in these patients, preliminary studies of the non-gadolinium-based contrast agent ferumoxytol are demonstrating promising results, and FDA approval is anticipated in the near future.

Invasive Imaging Modalities

IVUS

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was first introduced in the early 1990s and has since gained acceptance as a tool for diagnosing and treating an array of vascular diseases (Figure 1C), including coronary artery disease when used as an adjunct to angiography.16 Moreover, this invasive imaging technique is best suited for use as an adjunct during a planned endovascular intervention for patients requiring limb salvage. The particular advantages of IVUS include a reduced need for contrast and the highly accurate assessment of lumen area, residual stenosis, and completeness of treatment. Because it is an invasive procedure, IVUS increases costs and procedure times and cannot be performed in the infrapopliteal arteries. In a single study directly comparing IVUS to DSA in PAD, stenosis was measured at an average of 10% greater by IVUS than DSA.17 This may be of significant value as stent failure has been attributed to stent oversizing; thus, determining an accurate diameter could potentially affect outcomes. Studies examining IVUS in the coronary vasculature indicate that, compared to IVUS, DSA underestimates residual atheroma burden following atherectomy.18, 19 IVUS allows for evaluation of plaque morphology, plaque eccentricity, and lesion length, often helping in procedural decision making; it also demonstrates plaque fracture and arterial wall dissection more often than angiography. Coronary angiograms frequently underestimate disease burden, whereas IVUS identifies residual plaque burden and minimal lumen diameter as the most powerful predictors of clinical outcome (restenosis).20 Although these findings have not been studied in PAD, they serve as important points for consideration in evaluating iliac and superficial femoral artery disease.

CO2 Angiography

In the United States, more than 1.2 million individuals have a concomitant diagnosis of renal insufficiency and PAD. For these patients, avoiding the use of nephrotoxic contrast agents is important for preserving renal function. Initially described by Hawkins and Caridi, CO2 angiography offers a safe, reliable alternative.21 Having a lower radiodensity than soft tissue, CO2 displaces blood from the artery lumen, allowing images to be obtained using traditional DSA techniques. The utility of CO2 angiography has been well described for aortic imaging but was considered to have limited use in the lower extremity vasculature because the gas column breaks up as it travels distally. However, Seeger and colleagues showed that more than 90% of images obtained of the aortoiliac, common femoral, superficial femoral, and profunda arteries were of excellent or good quality.22 Therefore, while CO2 angiography is limited for use in the infrapopliteal vessels, it can be used to reduce contrast load for imaging aortofemoral segments (Figure 3) and should not be overlooked in this patient population.

Figure 3.

(A, B) Above-knee CO2 and (C, D, E) infrapopliteal contrast DSA images in a patient with diffuse occlusive disease and elevated creatinine. DSA: digital subtraction angiography

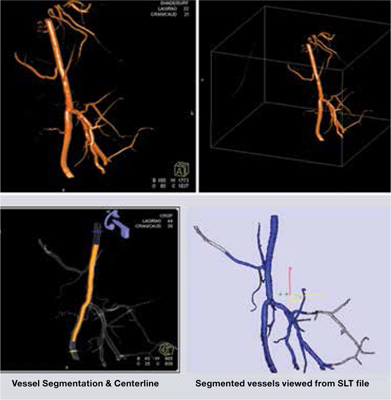

Rotational Angiography

Rotational angiography has been used successfully in neuroradiological interventions and is gaining widespread use as new hybrid operating rooms are introducing vascular surgeons to this valuable tool. Several companies provide this technology on their systems, including Siemens (DynaCT) and Philips (XperCT). Rotational angiography is particularly well suited for difficult aortoiliac interventions: it allows appropriate sizing of stents, it depicts the tortuosity of the aortoiliac segment well including the internal iliac artery, it can identify proper paths for catheters, and it accurately identifies plaque. The volume of contrast injected can be modified for aorta and iliac arteries, but essentially the acquisition takes 8 seconds. The acquired images are transferred to a work station where reconstructions are processed (Figure 4). This step generates a 3D volume that can be rotated and viewed in any direction, and cut planes can also be made at any position. According to tests by Van den Berg et al., the errors in measurements using this technique are less than 2%; if one considers that target vessels in peripheral interventions are no larger than 10 mm, then indeed we are dealing with a small error of less than 0.5 mm.23 Our team at the Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center has seen similar results in our clinical experience, with extremely good correlation to IVUS, although this experience is only anecdotal.

Figure 4.

Cone beam CT images of femoral artery and proximal anastomosis of a femoral-popliteal bypass.

These systems are also available with a variety of software packages such as “virtual” stent, where measurement and deployment of the stent is predicted based on the virtual measurements. Pozzi-Mucelli et al. found a good level of agreement between the measurements of virtual stenting and the actual deployed stents.24 We have used similar techniques when measuring, for example, isolated common iliac aneurysms (Figure 5). In short, while there currently is no evidence pointing towards improved outcomes, rotational angiography has the potential to benefit outcomes, decrease procedure difficulty and times, and ultimately reduce complications.

Figure 5.

Cone beam CT reconstruction of isolated common iliac artery aneurysm.

Conclusion

Patients at risk for limb loss secondary to peripheral arterial disease and resultant critical limb ischemia are difficult to manage, as they often have multiple medical comorbidities and diffuse arterial disease. In addition to proper medical optimization, successful limb salvage requires highly accurate imaging of the diseased segments. With advances in imaging technology, vascular surgeons are now able to obtain such high-quality images through noninvasive means for preoperative evaluation and planning. In addition, alternatives to standard DSA allow for intravascular imaging, renal protective contrast enhancement, and CT-quality vascular reconstruction. These imaging modalities have been shown to be at least as good as the “gold standard” and have provided surgeons with an array of tools to assist in imaging and hopefully improve outcomes.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: All authors have completed and submitted the Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal Conflict of Interest Statement and none were reported.

Funding/Support: The authors have no funding disclosures.

Contributor Information

Cassidy Duran, Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center, The Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas

Jean Bismuth, Methodist DeBakey Heart & Vascular Center, The Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas

References

- 1.Kashyap VS, Pavkov ML, Bishop PD, Nassoiy SP, Eagleton MJ, Clair DG, et al. Angiography underestimates peripheral atherosclerosis: lumenography revisited. J Endovasc Ther. 2008;15(1):117–25. doi: 10.1583/07-2249R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenhagen P, White RD, Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM. Coronary imaging: angiography shows the stenosis but IVUS, CT, and MRI show the plaque. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(8):713–9. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.70.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba R, Konno Y, Ueda K, Ikeda S. Comparison of flat-panel detector and image-intensifier detector for cone-beam CT. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2002;26(3):153–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-6111(02)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalender WA, Kyriakou Y. Flat-detector computed tomography (FD-CT). Eur Radiol. 2007;17(11):2767–79. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0651-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandyk DF. Surveillance after lower extremity arterial bypass. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2007;19(4):376–83. doi: 10.1177/1531003507310460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schertler T, Wildermuth S, Alkadhi H, Kruppa M, Marincek B, Boehm T. Sixteen-detector row CT angiography for lower-leg arterial occlusive disease: analysis of section width. Radiology. 2005;237(2):649–56. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin GD, Schmidt AJ, Logan LJ, Sofilos MC. Multi-detector row CT angiography of lower extremity arterial inflow and runoff: initial experience. Radiology. 2001;221(1):146–58. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2211001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ota H, Takase K, Igarashi K, Chiba Y, Haga K, Saito H, et al. MDCT compared with digital subtraction angiography for assessment of lower extremity arterial occlusive disease: importance of reviewing cross-sectional images. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(1):201–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.1.1820201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Met R, Bipat S, Legemate DA, Reekers JA, Koelemay MJW. Diagnostic performance of computed tomography angiography in peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(4):415–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.301.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellegrottaglie S, Sanz J, Macaluso F, Einstein AJ, Raman S, Simonetti OP, et al. Technology Insight: magnetic resonance angiography for the evaluation of patients with peripheral artery disease. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(12):677–87. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koelemay MJ, Lijmer JG, Stoker J, Legemate DA, Bossuyt PM. Magnetic resonance angiography for the evaluation of lower extremity arterial disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2001;285(10):1338–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.10.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glickerman DJ, Obregon RG, Schmiedl UP, Harrison SD, Macaulay SE, Simon HE, et al. Cardiac-gated MR angiography of the entire lower extremity: a prospective comparison with conventional angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(2):445–51. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.2.8686623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yucel EK, Kaufman JA, Geller SC, Waltman AC. Atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremity: prospective evaluation with two-dimensional time-of-flight MR angiography. Radiology. 1993;187(3):637–41. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Matsuoka Y, Ogawa Y, Hayashi H, Hashmi R, et al. Aortoiliac and lower extremity arteries: comparison of three-dimensional dynamic contrast-enhanced subtraction MR angiography and conventional angiography. Radiology. 1999;210(3):683–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99fe22683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelemans PJ, Leiner T, de Vet HC, van Engelshoven JM. Peripheral arterial disease: meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of MR angiography. Radiology. 2000;217(1):105–14. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.1.r00oc11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nissen SE, Yock P. Intravascular ultrasound: novel pathophysiological insights and current clinical applications. Circulation. 2001;103(4):604–16. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthurs ZM, Bishop PD, Feiten LE, Eagleton MJ, Clair DG, Kashyap VS. Evaluation of peripheral atherosclerosis: a comparative analysis of angiography and intravascular ultrasound. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(4):933–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura S, Mahon DJ, Leung CY, Maheswaran B, Gutfinger DE, Yang J, et al. Intracoronary ultrasound imaging before and after directional coronary atherectomy: in vitro and clinical observations. Am Heart J. 1995;129(5):841–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koschyk DH, Nienaber CA, Schaps KP, Twisselmann T, Hofmann T, Lund GK, et al. Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance on directional coronary atherectomy. Z Kardiol. 2000;89(4):301–6. doi: 10.1007/s003920050489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sgura FA, Di Mario C. [New methods of coronary imaging II. Intracoronary ultrasonography in clinical practice]. Ital Heart J Suppl. 2001;2(6):579–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins IF, Caridi JG. Carbon dioxide (CO2) digital subtraction angiography: 26-year experience at the University of Florida. Eur Radiol. 1998;8(3):391–402. doi: 10.1007/s003300050400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeger JM, Self S, Harward TR, Flynn TC, Hawkins IF., Jr. Carbon dioxide gas as an arterial contrast agent. Ann Surg. 1993;217(6) doi: 10.1097/00000658-199306000-00011. 688–97; discussion 697-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van den Berg JC, Moll FL. Three-dimensional rotational angiography in peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther. 2003;10(3):595–600. doi: 10.1177/152660280301000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pozzi-Mucelli F, Calgaro A, Belgrano M, Cernic S, Pozzi-Mucelli R. Virtual stenting of iliac arteries: a new technique for choosing stents and stent-grafts by means of 3D rotational angiography. Preliminary data. Radiol Med. 2004 Nov-Dec;108(5-6):494–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]