Abstract

Canadian subspecialty residency training programs are developed around the learning objectives listed in the seven Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) criteria. Delivering content on objectives outside of those traditionally acquired in clinical rotations can be a challenge. In the present article, the planning process, curriculum development, and evaluation and assessment of a national subspecialty conference model in providing CanMEDS objective-based content sessions in the categories other than Medical Expert (Professional, Scholar, Communicator, Collaborator, Manager and Health Advocate) is described. It is hypothesized that the development of a CanMEDS objective-based curriculum would be positively received by subspecialty residents attending this conference. Attendees of sessions in a two-year curriculum cycle assessed the content as valuable, relevant and effective. The application of this process can be useful to other subspecialty residency training programs to meet the needs of their CanMEDS objective-based training requirements.

Keywords: Emergency medicine, Medical education, Paediatrics

Abstract

Les programmes canadiens de formation de résidence en surspécialité sont élaborés conformément aux objectifs d’apprentissage énumérés dans les sept rôles CanMEDS. Il peut être difficile de présenter du contenu au sujet de rôles qui ne font pas partie de ceux habituellement acquis lors des rotations cliniques. Dans le présent article, les chercheurs décrivent le processus de planification, l’élaboration du programme et l’évaluation d’un modèle de congrès national de surspécialité au moyen de séances fondées sur les autres rôles CanMEDS que celui d’expert médical (professionnel, érudit, communicateur, collaborateur, gestionnaire et professionnel de la santé). Ils postulaient que les résidents en surspécialité qui participaient au congrès accueilleraient favorablement un programme reposant sur les rôles CanMEDS. D’après l’évaluation des participants aux séances faisant partie d’un programme de deux ans, le contenu était perçu comme digne d’intérêt, pertinent et efficace. La mise en application de ce processus peut être utile à d’autres programmes de formation en surspécialité qui désirent respecter leurs besoins de formation reposant sur les rôles CanMEDS.

The subspecialty of paediatric emergency medicine (PEM) was recognized by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) in 2000 (1). The specific training requirements of subspecialty residency (or ‘fellowship’) training were established by the RCPSC using Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) (2) categories to address the learning objectives for physicians seeking formal certification in PEM (3). Since the development of these subspecialty training requirements, some training programs have struggled to adequately address all of the CanMEDS categories in the curriculum of academic sessions or formal rotations for their subspecialty residents (or ‘fellows’). In Canada, there have been no formal subspecialty postgraduate medical conference for Canadian trainees in PEM with content and objectives that were organized in a format that met the standards set by the RCPSC. The United States has held an Annual Pediatric Emergency Fellows Conference since 1994 (4), which has been sparsely attended by Canadian subspecialty PEM residents in lieu of a Canadian conference. In the present article, we describe the development and evaluation of the Canadian Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellows Education Day Conference, designed specifically to cover the required CanMEDS roles and objectives that training programs usually find difficult to address as part of their regular curriculum. We hypothesize that the development of a CanMEDS objective-based curriculum would be positively received by sub-specialty residents attending this conference.

METHODS

Original content development

In 2007, a committee was formed to plan an annual Canadian PEM resident education conference. Its membership consisted of five PEM faculty (including the subspecialty residency training program director and residency training committee members) and five subspecialty residents (SSRs) from the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, British Columbia). The intent of this conference was to deliver content not typically covered in an extensive fashion in PEM subspecialty training programs. Specifically, these related to objectives in the CanMEDS categories other than Medical Expert: Professional, Scholar, Communicator, Collaborator, Manager and Health Advocate.

Over the course of three months, the committee conducted a needs assessment by surveying other SSRs and PEM faculty for areas of subspecialty residency training that could be delivered in objective-based content presentations or activities. The committee reviewed the RCPSC training objectives for PEM and developed a list of potential conference topics, with the intent of including addressing training objectives from all CanMEDS categories within the conference curriculum. Objectives, based on the RCPSC training objectives, were grouped into CanMEDS competencies for each potential conference topic. The concept for a Canadian PEM resident education conference was presented to Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC), which subsequently agreed to incorporate this content into its annual national conference.

Logistics and planning

In 2008, a new PERC conference planning committee, comprised of Canadian PEM faculty (subspecialty residency training program directors and faculty, which included the authors) from paediatric hospitals across the country and one SSR representative, was convened by the PERC executive to develop the PERC Fellows Education Day. The curriculum topics generated from the efforts of the British Columbia Children’s Hospital (Vancouver, British Columbia) committee were reviewed and, for the majority of curriculum topics, committee members affirmed that these topics were lacking in their own institutions’ training curriculum. Through committee discussions, it was discovered that other curriculum items developed by the British Columbia Children’s Hospital committee were addressed at some centres but not by others. The committee placed priority, by consensus, on the curriculum topics that were not addressed at most centres in considering which topics would be of value in a conference-based curriculum cycle. Consensus was obtained by majority vote among committee members. Due to the large number of important topics that were considered desirable, a repeating two-year curriculum cycle was developed. Complete curriculum coverage would be achieved within the typical two-year duration of Canadian PEM training programs. Curriculum topics were assigned into each part of the cycle by taking into account various factors, such as diversity of topics and speakers, interactivity, small versus large group sessions and applicability for level of training. CanMEDS-specific learning objectives were developed for each session of the educational day. For example, for the session entitled “Being A Fellow: How to get the most out of subspecialty training”, objectives based on Communicator, Collaborator and Scholar competencies were developed; for the session entitled “The Next Step: Finding your first job”, objectives based on Manager and Professional competencies were developed.

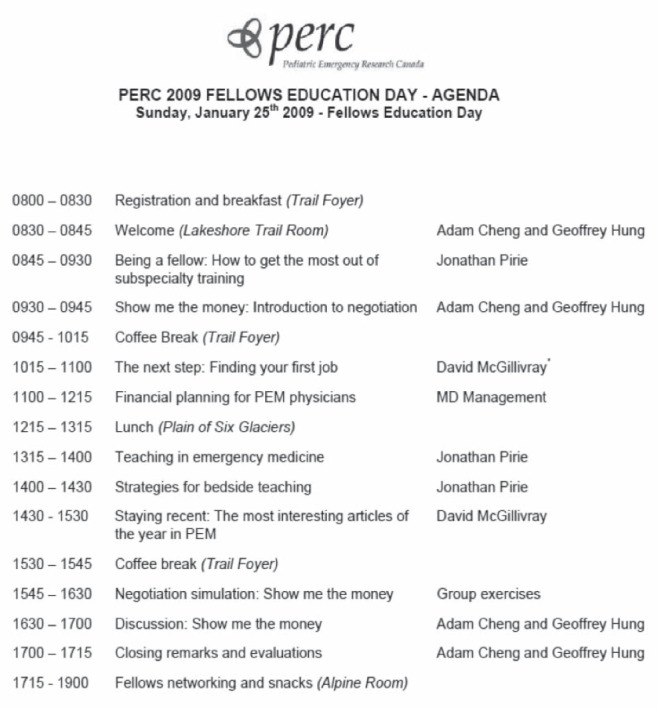

The first PERC Fellows Education Day was held in January 2009 at Lake Louise (Alberta) (Figure 1) as part of the PERC annual national conference.

Figure 1).

2009 Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Fellows Education Day agenda. PEM Paediatric emergency medicine

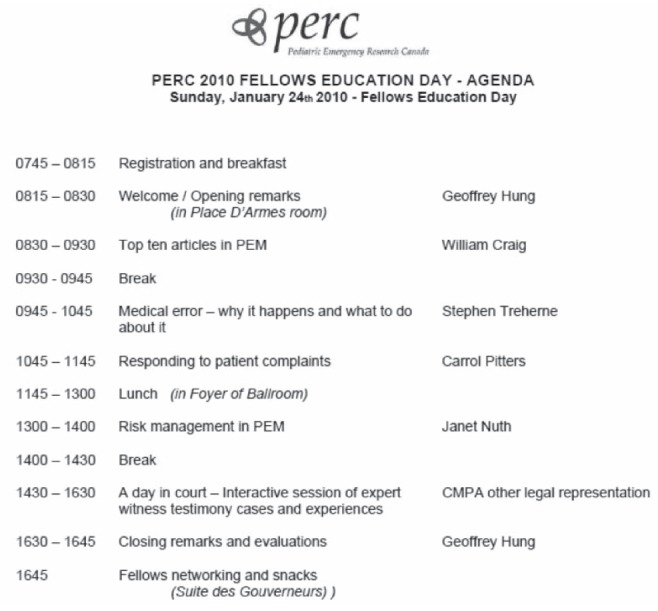

The PERC conference planning committee reconvened in Spring 2009 to plan the second half of the two-year curriculum cycle for the PERC Fellows Education Day and review the evaluations of the first conference. Due to the feedback received from the evaluations, one curriculum topic was repeated (‘The Year’s Best Papers’) and was included in the second half of the curriculum cycle, to be presented by a different speaker from the year before. Once again, CanMEDS-specific learning objectives were developed for each session. The second PERC PEM Fellows Education Day was held January 2010 in Quebec City, Quebec (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

2010 Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Fellows Education Day agenda. PEM Paediatric emergency medicine

External financial support

Speakers invited to the 2009 and 2010 PEM Fellows Education Day conferences were supported in part by continuing professional development grants awarded by the respective Regional Advisory Committees of the RCPSC in the geographical areas where conferences were held. Attendance by SSRs from across the country was supported by individual programs.

Evaluation

Paper-based evaluation forms were developed for each session in the agendas. Evaluation forms were developed using templates that had been used to evaluate previous PERC annual research meetings and invited speaker presentations. Separate sections of the evaluation forms were tailored to evaluate the content, objectives and presentation effectiveness for each individual session.

Using these evaluation forms, SSR attendees were requested to evaluate the content of each session. Evaluation items focused around the desired CanMEDS objective to be covered in each session, speaker effectiveness, presentation effectiveness and the relevance of the topic to the educational needs of the SSR attendee. Owing to the complexity of simulation-based sessions, evaluation items for the negotiation simulations were evaluated more rigorously around experiences with the simulation, usefulness of group debriefing exercises and overall quality of the presentation. The evaluation forms assessed attendee feedback using a five-point Likert scale (5 = ‘strongly agree’, 4 = ‘agree’, 3 = ‘neutral’, 2 = ‘disagree’, and 1 = ‘strongly disagree’) as a response to each evaluation item. A blank section was also provided at the end of each evaluation form for attendees to provide additional written feedback.

At the closing of the PEM Fellows Education Day, each SSR attendee also had the opportunity to provide their overall satisfaction with the elements of the meeting such as location, timing and conference facilities. A separate section of the evaluation form asked for overall comments as well as suggestions of speakers or topics that residents would find useful as part of a future PEM Fellows Education Day curriculum content development. Paper evaluation forms were collected by the conference organizers and entered into an Excel (MicroSoft Corporation, USA) spreadsheet for data analysis.

RESULTS

Twenty-six participants attended the inaugural PEM Fellows Education Day in 2009, and 28 participants attended the second PEM Fellows Education Day in 2010. At the 2009 conference, 23 of the attendees were PEM SSRs and three were staff physicians; at the 2010 conference 26 attendees were PEM SSRs and two were staff physicians. There were eight general paediatric residents attending both the 2009 and 2010 conference. Eight of 26 attendees (31%) to the 2010 conference had attended the 2009 conference. The SSRs who attended the 2009 and 2010 conferences represented nine of the 10 Canadian RCPSC-accredited PEM SSR training programs. At the 2010 conference, two residents also attended from other Canadian institutions without a formal PEM SSR training program and one resident from Portugal who was currently working on a research project with other PERC members also attended. During each year of the inaugural two-year curriculum cycle, attendance numbers represented approximately 62% of total PEM SSRs in RCPSC PEM training programs at the time.

Evaluation results were available for 26 of 26 (100%) attendees for the 2009 conference, and 27 of 28 (96%) attendees for the 2010 conference. Individual session evaluation results are presented in Table 1 for the 2009 PEM Fellows Education Day, and Table 2 for the 2010 PEM Fellows Education Day. Overall, participants favourably evaluated the sessions, finding the content valuable, understandable and helpful in meeting the needs of their subspecialty residency training.

TABLE 1.

Selected individual evaluation item and overall session scores for 2009 Pediatric Emergency Medicine (PEM) Fellows Education Day

| Being a fellow: How to get the most out of subspecialty training | Average Score* |

|---|---|

| This session provided a strong rational for subspecialty training | 4.12 |

| I was able to learn the value of subspecialty training | 3.96 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.31 |

| The next step: Finding your first job | |

| This session provided me with knowledge on how to search for my first job | 4.50 |

| I was able to learn the value of finding the right job to fit with my research goals | 4.48 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.63 |

| Teaching in emergency medicine | |

| This session provided me with knowledge of how to be a good teacher/mentor | 4.39 |

| I was able to learn the value of teaching in emergency medicine | 4.22 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.44 |

| Strategies for bedside teaching | |

| This session provided me with knowledge of how to be a good teacher/mentor | 4.38 |

| I was able to learn the value of bedside teaching | 4.42 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.49 |

| Financial planning for PEM physicians | |

| This session provided me with knowledge and skills to better plan my financial future as a physician | 4.13 |

| I was able to learn the value of financial planning | 4.17 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.11 |

| Staying recent: The most interesting articles of the year in PEM | |

| This session provided me with knowledge about the most important research in PEM over the past year | 4.38 |

| I was able to learn the value of staying recent | 4.46 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.50 |

| Show me the money: Negotiation exercises | |

| The ‘negotiation simulation’ was a positive and useful learning experience | 4.00 |

| The simulated negotiation reflected something I could potentially encounter in the future | 3.95 |

| The group debriefing was a useful and positive learning experience | 3.77 |

| The instructors were enthusiastic and knowledgeable | 4.55 |

| The negotiation session addressed learning objectives that had not been taught during my fellowship | 3.95 |

| The format of the session was an effective way of addressing negotiation specific issues | 3.95 |

| Negotiation training should be a mandatory part of my training and education as a PEM physician | 3.77 |

| Overall evaluation | 3.90 |

5 = ‘strongly agree’, 4 = ‘agree’, 3 = ‘neutral’, 2 = ‘disagree’, and 1 = ‘strongly disagree’

TABLE 2.

Selected individual evaluation item and overall session scores for 2010 Pediatric Emergency Medicine (PEM) Fellows Education Day

| Top 10 articles of 2009 | Average score* |

|---|---|

| This session provided me with knowledge about the most important research in PEM over the past year | 4.36 |

| I was able to learn the value of staying recent | 4.40 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.38 |

| Medical errors: Why they happen and what can be done | |

| This session provided me with knowledge on how to recognize and avoid common medical errors | 4.50 |

| I was able to learn the value and complexity of recognizing medical errors | 4.58 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.42 |

| Responding to patient complaints | |

| This session provided me with knowledge on how to respond to patient complaints | 4.19 |

| I was able to learn the value of appropriately responding to patient complaints | 4.31 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.22 |

| Risk management in PEM | |

| This session provided me with knowledge of risk management in PEM | 4.50 |

| I was able to learn the value of identifying and assessing risk in PEM | 4.62 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.51 |

| A day in court: Expert witness testimony | |

| This session provided me with useful information for future expert witness testimony | 4.52 |

| The group scenario was well organized | 4.67 |

| Overall evaluation | 4.61 |

5 = ‘strongly agree’, 4 = ‘agree’, 3 = ‘neutral’, 2 = ‘disagree’, and 1 = ‘strongly disagree’

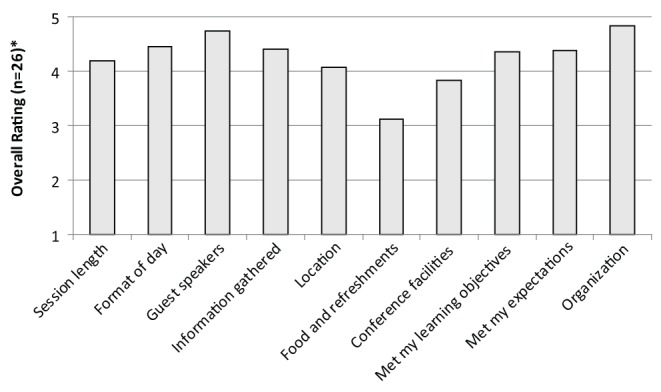

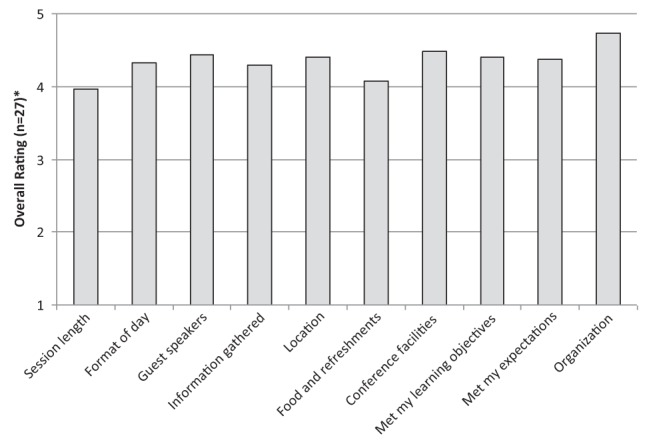

Overall conference evaluation results are presented in Figures 3 and 4. Participants highly rated the organization and format of the sessions, as well as finding that the content met their learning objectives and expectations. When asked if attendees would plan to be at a future PEM Fellows Education Day conference, 94.4% and 74% said ‘Yes’, respectively, in 2009 and 2010.

Figure 3).

Overall results for 2009 Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellows Education Day. *5 = ‘Strongly Agree’, 4 = ‘Agree’, 3 = ‘Neutral’, 2 = ‘Disagree’, and 1 = ‘Strongly Disagree’

Figure 4).

Overall results for 2010 Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellows Education Day. *5 = ‘Strongly Agree’, 4 = ‘Agree’, 3 = ‘Neutral’, 2 = ‘Disagree’, and 1 = ‘Strongly Disagree’

DISCUSSION

We have described the development process of a Canadian PEM SSR education conference, with the aim to deliver CanMEDS objectives that are typically not covered during clinical activities and elective rotations. Attendees highly positively rated the content, delivery and relevance of the conference. Content and curriculum development occurred with PEM SSR and expert faculty educator collaboration. The extensive curriculum required a logical and planned division of topics over a two-year conference cycle to ensure coverage of all of the planned sessions. Logistical support and financial support were required for the development of the conference agenda. Evaluation results from individual conference sessions demonstrate highly positive feedback from attendees on the session content, presentation and discussion. The presentations in the conference were rated as being very effective.

A single session at each conference presented the most current and important literature published in the preceding year. This was the only session that had similar learning objectives in both sessions, but with differing speakers and slightly different educational objectives. In each conference year, this evidence-based session was rated highly by attendees, who highly rated both the structure and the format of the session. This suggests that such a conference session, with structured relevant objectives, and that has applicability both in current training and in future clinical practice, can be presented by different speakers effectively.

Despite the infancy of this conference, it has been well received by residents and program directors of PEM subspecialty training programs (personal communication, Dr Farhan Bhanji). Program directors are adopting the conference content in their programs to support CanMEDS learning objectives in their educational activities. While some conference sessions delivered content specific to PEM, other sessions on topics such as communication, conflict resolution, career planning and negotiation are also applicable to other specialties accredited by the RCPSC. While it is not necessary or practical for training programs in other specialties and subspecialties to develop their own national annual conference, such shared objectives can lead to the development of institutional sessions in training centres, provided by local experts in these objectives, to provide this content in a session-based format similar to this annual PEM SSR education conference. While there was some funding support for the initial two-year curriculum cycle by the RCPSC, ongoing sustainable funding to obtain high-quality speakers is a concern for the future of this form of conference. The planning committee will work to explore alternative models of funding this meeting to ensure ongoing success of the program. Dissemination of the experience of this conference and the evaluation results would benefit residents in specialty and sub-specialty programs across Canada. Assessment of the success of this conference in being able to effectively deliver content to SSRs could be evaluated in the future through the testing of specific learning objectives of conference material through formats, such as objective structured clinical examination.

Our study had several limitations. Evaluations did not include demographics of the attendees, such as the current year of training in PEM of the participating SSR (eg, first year, second year, third year). Despite overall positive feedback, it is possible that particular sessions might have been of more value to some residents given their level of training, entry program into PEM (ie, paediatrics or emergency medicine) or other demographic factors. For example, residents in their first year of subspecialty training may find certain sessions more useful (eg, content on maximizing learning opportunities in training) compared with their colleagues who might be closer to completing their training. We were not able to identify which evaluations belonged to the eight attendees at both conferences to assess whether their feedback had changed between the 2009 and 2010 conference.

Another limitation was that our assessment tool did not record whether the respondent was an SSR or an attending physician. As such, it was not possible to extract the evaluation scores of attending physicians from the total scores. Because attending physicians at the conference comprised a small percentage of the total attendees, their effect on the total scores would have been small as well. Because some SSRs attended the conference both years, it is possible that the high ratings obtained in the evaluation could be related to a selection bias. That being said, only a minority of SSRs attended both years, and the content from year to year was significantly different, which likely would have helped to mitigate this effect. Although session objectives and content were intended to apply to all levels of training in PEM, it is possible that evaluations of particular sessions may have been affected by resident demographics. It is anticipated that future evaluations will collect this information to detect trends in evaluations. Future studies may need to be performed to determine whether level-specific (eg, first or second year of subspecialty training) topic objectives and content needs to be developed. Finally, approximately 40% of trainees across the country did not attend the conference. We suspect that this is related to multiple variables, including funding, location, timing and logistics. We hope that the growth and popularity of this meeting will lead to improved funding for SSRs and a greater commitment from individual programs to support the attendance of their trainees in future years.

CONCLUSION

A session-based conference format may be used to successfully provide CanMEDS-based objective content of PEM SSR training programs to support the traditional rotation-based training. SSRs have favourably evaluated a rotating two-year curriculum cycle to deliver content designed to meet the needs of Professional, Scholar, Communicator, and Advocate roles and objectives in the CanMEDS format. Success of this curriculum and session format may be relevant to other specialty and subspecialty training programs aiming to deliver similar content. Additional study may be needed to evaluate whether content may be improved through the use of level-specific needs development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the subspecialty residents of the Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia (Vancouver, British Columbia) for their contributions to the development of the original conference curriculum. The authors also acknowledge the Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Fellows Education Day Committee for the 2009 and 2010 conferences: Dr Gina Neto, Dr Kelly Millar, Dr Dominic Allain and Dr Waleed Alqurashi. In particular, the authors thank Dr Martin Osmond for his insight and invitation to support the development of this conference through the support and infrastructure of the PERC annual conference.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGillivray D, Jarvis A. A history of paediatric emergency medicine in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2007;12:453–6. doi: 10.1093/pch/12.6.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada CanMEDS. < http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/index.php> (Accessed February 17, 2011).

- 3.The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada Information by Specialty or Subspecialty. < http://rcpsc.medical.org/information/index.php?specialty=462&submit=Select> (Accessed February 17, 2011).

- 4.Jaffe DM, Knapp JF, Jeffe DB. Outcomes evaluation of the 2005 National Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellows’ Conference. Ped Emerg Care. 2008;24:255–261. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31816bc7ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]