The intramembrane protease SPPL2a cleaves the NTF of invariant chain (CD74), which is essential for normal trafficking of MHC class II–containing endosomes and thus for B cell development and function.

Abstract

Regulated intramembrane proteolysis is a central cellular process involved in signal transduction and membrane protein turnover. The presenilin homologue signal-peptide-peptidase-like 2a (SPPL2a) has been implicated in the cleavage of type 2 transmembrane proteins. We show that the invariant chain (li, CD74) of the major histocompatability class II complex (MHCII) undergoes intramembrane proteolysis mediated by SPPL2a. B lymphocytes of SPPL2a−/− mice accumulate an N-terminal fragment (NTF) of CD74, which severely impairs membrane traffic within the endocytic system and leads to an altered response to B cell receptor stimulation, reduced BAFF-R surface expression, and accumulation of MHCII in transitional developmental stage T1 B cells. This results in significant loss of B cell subsets beyond the T1 stage and disrupted humoral immune responses, which can be recovered by additional ablation of CD74. Hence, we provide evidence that regulation of CD74-NTF levels by SPPL2a is indispensable for B cell development and function by maintaining trafficking and integrity of MHCII-containing endosomes, highlighting SPPL2a as a promising pharmacological target for depleting and/or modulating B cells.

The concept of intramembrane proteases (I-CLIPs) cleaving within the phospholipid bilayer was initially put forward based on processing of the sterol regulatory element–binding protein (SREBP; Brown and Goldstein, 1997; Wolfe and Kopan, 2004). Usually, I-CLIPs operate as part of a proteolytic sequence referred to as regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP; Lichtenthaler et al., 2011). Intracellular domains (ICDs) of several RIP substrates function as signaling molecules after their proteolytic release as exemplified by the Notch pathway (De Strooper et al., 1999; Urban and Freeman, 2002). Based on their catalytic center, serine, metallo, or aspartyl I-CLIPs (Wolfe, 2009) can be differentiated. The group of aspartyl I-CLIPs comprises the presenilins being part of the γ-secretase complex and the SPP/SPPL (signal-peptide-peptidase[-like]) family, with apparent specificity for transmembrane proteins in type 1 and type 2 orientation, respectively (Wolfe and Kopan, 2004).

Among the SPPLs, SPPL2a appears to be unique in its residence in lysosomes/late endosomes (Behnke et al., 2011). To date, only TNF (Friedmann et al., 2006; Fluhrer et al., 2006), Fas ligand (Kirkin et al., 2007), and Bri2 (Martin et al., 2008) have been identified as SPPL2a substrates by in vitro studies. In DCs, RIP of TNF has been shown to influence expression of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-12 (Friedmann et al., 2006). Beyond that, the physiological significance of SPPL2a-mediated RIP is unknown.

Based on its presence in late endocytic compartments and the specificity for type 2 membrane proteins, we searched for novel substrates of SPPL2a and investigated the invariant chain (li, CD74) as a candidate. This protein has been extensively studied as a chaperone of MHC class II complexes (MHCII), which present antigens to CD4+ helper T cells in a key process of adaptive immunity (Neefjes et al., 2011). In antigen-presenting cells, the type 2 transmembrane protein CD74 binds the newly assembled MHCII dimers in the ER, thereby preventing premature peptide binding, and directs the nonameric α3β3li3 complex to specialized endosomes referred to as MHCII compartments. There, MHCII is loaded with antigen-derived peptides, after the luminal domain of CD74 has been removed by sequential proteolytic degradation (Matza et al., 2003).

Consistently, absence of CD74 in mice disrupts maturation of MHCII, antigen presentation and development of CD4+ T cells (Bikoff et al., 1993). However, CD74-deficient mice also show compromised B cell maturation beyond the transitional developmental stages, leading to impaired humoral immune responses (Shachar and Flavell, 1996). Truncated N-terminal fragments (NTFs) of CD74 that are devoid of the MHCII binding CLIP (class II–associated li chain peptide) segment were reported to rescue maturation of B cells in these mice (Matza et al., 2002b). Based on this observation, an intrinsic and MHCII-independent role of CD74 by providing specific signals for B cell maturation was suggested. According to this concept, release of the intracellular domain (ICD) of CD74 by a yet unknown intramembrane protease from the membrane-bound N-terminal CD74 fragment (NTF) is required for transducing these maturation signals (Matza et al., 2002a; Becker-Herman et al., 2005). Downstream effects of this process were shown to be diverse (Starlets et al., 2006; Lantner et al., 2007), including activation of the NF-κB pathway (Matza et al., 2002a), and dependent on the transcription factor TAFII105 (Matza et al., 2001). However, the molecular details of the intramembrane cleavage of CD74 and ICD-mediated signaling remain unclear to date. Furthermore, this concept has been challenged by the observation that additional ablation of all MHCII subunits (Madsen et al., 1999) was able to completely restore the B cell deficiency of CD74−/− mice (Maehr et al., 2004). In contrast to the model discussed above, these findings clearly indicated that the mechanisms leading to the B cell maturation defect in the absence of CD74 involve and depend on MHCII. In addition, neither CD74 nor MHCII appear to be absolutely essential in developing B cells because B cell maturation was apparently not impaired in CD74-MHCII double-deficient mice (Maehr et al., 2004).

In this study, we present evidence in vitro and in vivo that SPPL2a is the postulated I-CLIP of CD74, and we also clarify the significance of this proteolytic event for B cell development and homeostasis. SPPL2a-deficient mice accumulate significant amounts of CD74 NTF due to impaired turnover by RIP, and show arrested B cell development at the T1 stage, in addition to functional defects of the residual B cells. However, this phenotype was significantly alleviated in SPPL2a-CD74 double-deficient mice. Therefore, we propose that the primary purpose of CD74 intramembrane cleavage mediated by SPPL2a is to tightly control the level of the CD74 NTF. We demonstrate that this NTF is capable of perturbing membrane traffic in the endocytic system documented by the accumulation of endosomal vacuoles in SPPL2a−/− B cells and secondarily interferes with cellular signaling pathways critical for developing B cells exemplified by reduced surface expression levels of the BAFF receptor (BAFF-R) and B cell antigen receptor (BCR) induced Ca2+ mobilization. Hence, we have identified a novel molecular mechanism mediating tight control of CD74 NTF levels, a process that is indispensable for cellular homeostasis of B cells. Based on this, pharmacological inhibition of SPPL2a may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for depleting B cells.

RESULTS

SPPL2a is the postulated intramembrane protease cleaving CD74

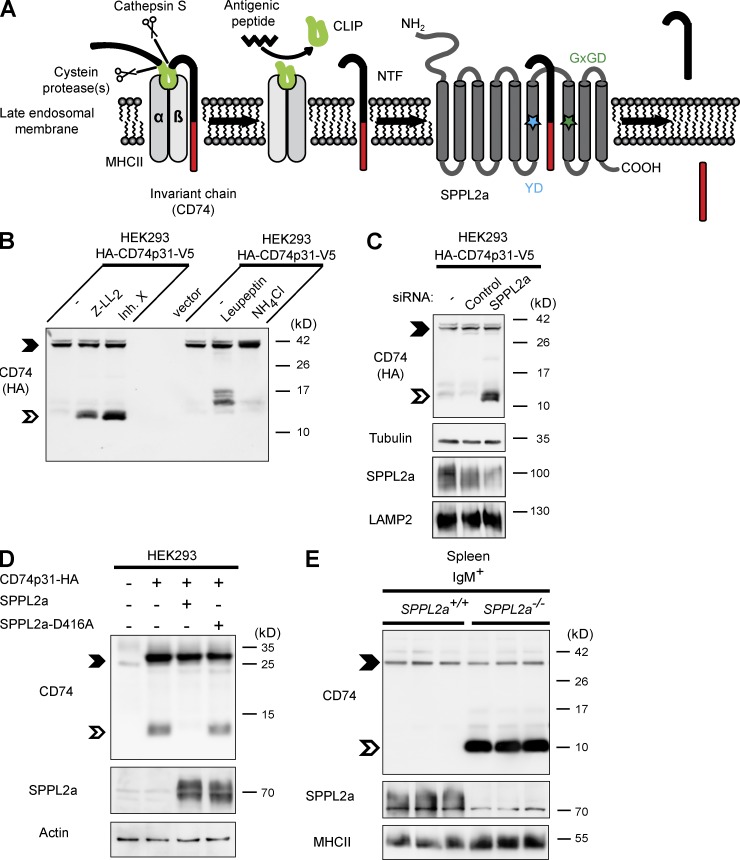

We evaluated the CD74 NTF, which, after removal of the CLIP segment by cathepsin S (Fig. 1 A), remains as a novel substrate of the poorly characterized intramembrane protease SPPL2a. We applied (Z-LL)2-ketone or the inhibitor X (L-685,458), which are established SPP/SPPL inhibitors (Weihofen et al., 2003; Friedmann et al., 2006), to HEK293 cells stably overexpressing epitope-tagged murine CD74 (Fig. 1 B). The inhibitor treatment induced stabilization of a CD74 NTF that was distinctly smaller than those CD74 degradation intermediates detected after inhibition of cysteine proteases by leupeptin (Fig. 1 B; Matza et al., 2003). When lysosomal acidification was impaired by NH4Cl, accumulation of full-length CD74 was induced. In a more specific approach, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown of SPPL2a in CD74-expressing HEK293 cells (Fig. 1 C). This increased the amount of CD74 NTF in a manner similar to the inhibitor treatment. In steady state, only low levels of this CD74 NTF were detectable (Fig. 1 B), presumably because of rapid turnover by endogenous SPPL2a. However, the steady-state level of CD74 NTF in transfected HEK293 cells could be even further reduced by co-expressing CD74 and SPPL2a (Fig. 1 D). This was not observed with the catalytically inactive SPPL2a-D416A variant. Collectively, these different experimental approaches strongly indicated that SPPL2a is responsible for the turnover of CD74 NTF.

Figure 1.

The intramembrane protease SPPL2a cleaves CD74 NTF. (A) Scheme of proteolytic degradation of CD74 in MHCII compartments, where the luminal domain is removed in a stepwise fashion by endosomal proteases and finally released from the MHCII dimer by cathepsin S. A small fragment (CLIP) persists inside the peptide-binding groove of MHCII, which is subsequently replaced with an antigenic peptide before the MHCII–peptide complex is transported to the plasma membrane. The remaining transmembrane NTF (82 aa) of CD74 is then proteolyzed by SPPL2a. The catalytically critical YD and GxGD motifs of SPPL2a are indicated by colored asterisks. (B) HEK293 cells stably expressing the p31 isoform of CD74 (HA-CD74p31-V5) were treated with 10 µM (Z-LL)2-ketone, 1 µM inhibitor X, 100 µM leupeptin or 25 mM NH4Cl for 5 h. The CD74 NTF is indicated by the open arrowheads. Full-length CD74 (closed arrowheads) and CD74 NTF were detected with anti-HA recognizing the epitope tag fused to the N terminus of the protein. (C) Transient knockdown of SPPL2a in HEK293 cells stably expressing HA-tagged CD74 (HA-CD74p31-V5). SPPL2a and the lysosomal membrane protein LAMP2 as control were analyzed in carbonate-washed membranes from the same batch of cells for enhancing SPPL2a detectability. (D) SPPL2a or the inactive D416A mutant were transiently co-expressed with CD74, followed by detection with anti-CD74 (In-1). (E) Using an antibody against an N-terminal epitope of CD74, endogenous CD74 was analyzed in splenic IgM+ B cells isolated from SPPL2a−/− and control mice. (B–E) Electrophoretic separation before detection of CD74 was performed by standard Tris-Glycine SDS-PAGE (D) or using a Tris-Tricine buffer system (B, C, and E) with improved resolution in the low-molecular weight range. Equal protein loading was confirmed as indicated. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

B cells of SPPL2a−/− mice accumulate CD74 NTF

To confirm the role of SPPL2a for RIP of CD74 in vivo and to scrutinize the physiological relevance of this process, we generated SPPL2a-deficient mice (Fig. 2 A), which were viable, fertile, and without any overt impairment. We specifically analyzed the processing of endogenous CD74 in SPPL2a−/−-purified IgM+ splenic B cells (Fig. 1 E). Although CD74 NTF was hardly detectable in wild-type B cells, SPPL2a-deficient B cells exhibited large amounts of accumulating NTF, demonstrating that in vivo active SPPL2a is also required for complete degradation of CD74 and that B cells from SPPL2a−/− mice fail to perform RIP of CD74. Similar results were obtained for other CD74-expressing cell types, such as BM-derived DCs (BMDCs) and splenic CD11c+ DCs (unpublished data).

Figure 2.

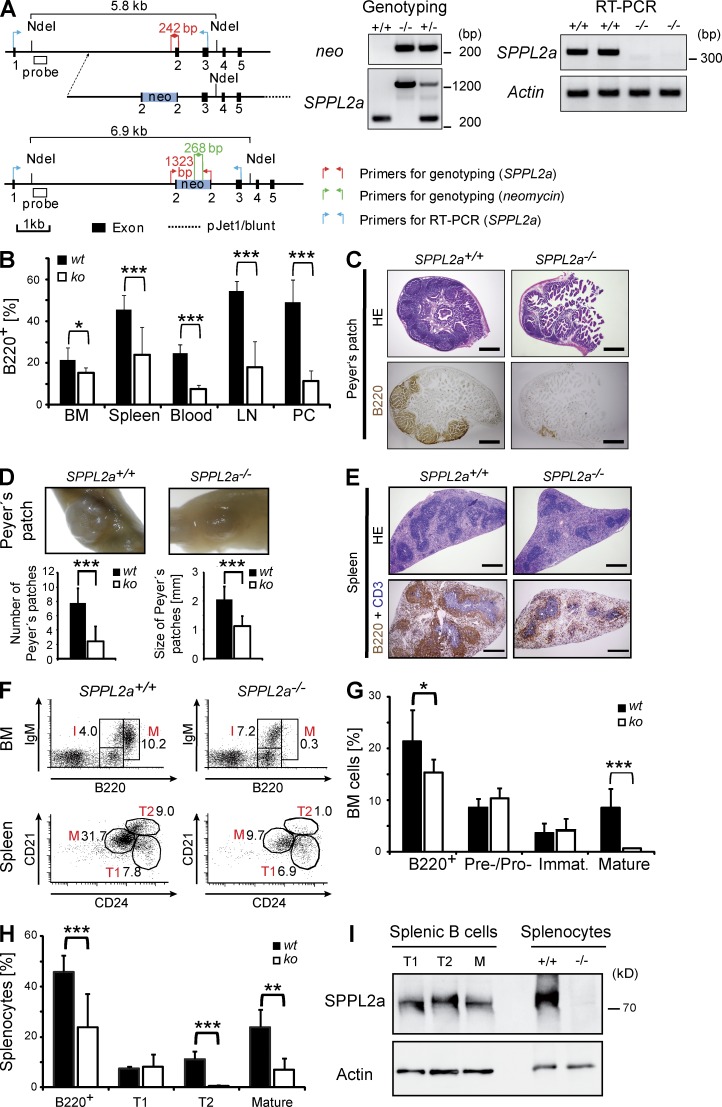

SPPL2a deficiency leads to impaired B cell development and function. (A) Generation of SPPL2a-deficient mice. The exon–intron structure of the murine SPPL2a gene, layout of the targeting construct, and structure of the targeted locus are depicted. Positions of primers and probes used for genotyping by PCR and Southern blot, respectively, are indicated. Genotyping of SPPL2a−/− mice was performed by PCR. DNA isolated from SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− tail biopsies was amplified with either gene-specific (SPPL2a) or neomycin-specific primers. Total RNA was isolated from SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts. After reverse transcription, primers annealing in exon 1 and exon 3 of the SPPL2a ORF as indicated were used to amplify a 342-bp fragment of the SPPL2a wild-type ORF from the cDNA. In parallel, appropriate primers for a fragment of β-actin were used as control. (B) The frequency of B cells (B220+, % of PI− cells) in BM, spleen, blood, LNs, and the peritoneal cavity (PC) of SPPL2a−/− compared with SPPL2a+/+ mice. Mean ± SD; n = 6–12. ***, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. (C) Representative sections of Peyer’s patches from SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or used for immunohistochemical visualization of B220+ B cells. Bars, 500 µm. (D) Mean number and diameter of Peyer’s patches in small intestines of SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− mice were determined by macroscopic inspection or measurement using a stereomicroscope, respectively. Mean ± SD; n = 9. ***, P < 0.001, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. (E) Regular splenic architecture and segregation of B (B220, brown) and T (CD3, blue) cells in SPPL2a−/− mice. Bars, 500 µm. (F–H) Frequencies of pre–/pro–, immature (I), and recirculating mature B cells (M) in the BM and transitional stage T1 and T2 and mature B cells (M) in spleens of SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− mice were determined by co-staining of B220 together with IgM or CD21 and CD24, respectively, and are shown as percentage of viable cells from a representative experiment (F, numbers indicate percentage of viable cells) or as mean ± SD; n = 7 (G; BM) or n = 9 (H; spleen). ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. (I) The expression level of SPPL2a was determined in FACS-sorted splenic B cell subsets (transitional stage T1 and T2, mature B cells) from wild-type mice by Western blotting. Actin levels were used for normalization. To control specificity of the SPPL2a antibody, splenocyte lysates isolated from wild-type and SPPL2a-deficient mice were included. One of two independent experiments is shown.

SPPL2a−/− mice show impaired B cell development

To assess the influence of reduced CD74 RIP on B cell development, we quantified B cells in different lymphatic tissues of SPPL2a−/− mice by flow cytometry (Fig. 2 B and Tables 1 and 2). Intriguingly, the amount of B cells (B220+) was significantly reduced in blood of SPPL2a−/− mice (7.6 vs. 24.6% of viable, propidium iodide–negative [PI−] cells), LNs (18 vs. 54.4% of PI− cells), and the peritoneal cavity (11.4 vs. 49.2% of PI− cells) in comparison to control mice. A decrease was detected for all mature B cell subsets, including marginal zone B cells and B1 B cells (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, at the sites of B cell differentiation, bone marrow, and spleen, a significant, though slightly less pronounced, decrease was observed (Fig. 2 B). The B cell deficiency was reflected in reduced spleen size (70% of wild-type) and atrophic Peyer’s patches (Fig. 2, C and D). However, the general morphology of spleen (Fig. 2 E) and LNs (not depicted), as well as the segregation of B and T cells into their respective zones, were found to be preserved. Furthermore, populations of other immune cells were not quantitatively changed in SPPL2a−/− mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Immune cells in different lymphatic tissues and peritoneal cells of wild-type and SPPL2a-deficient mice

| Cell type | SPPL2a+/+ | SPPL2a−/− | P-value | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| BM | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 21.4 | 6.1 | 15.3 | 2.5 | 0.031* |

| T cells | CD3+ | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.066 |

| Mature granulocytes | CD11b+ Gr1high | 63.4 | 9.6 | 70.5 | 1.4 | 0.137 |

| Immature granulocytes | CD11b− Gr1+ | 8.1 | 2.6 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 0.623 |

| DCs | CD11c+ | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2 | 0.714 |

| NK cells | CD49b+ | 2.6 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 0.078 |

| Spleen | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 45.6 | 6.6 | 23.9 | 13.1 | <0.001*** |

| Follicular B cells | B220+ CD21+ CD23+ | 29.5 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 4.1 | 0.023* |

| Marginal zone | B220+ CD21+ CD23−/low | 4.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.026* |

| T cells | CD3+ | 32.7 | 4.4 | 38.3 | 3.6 | 0.01* |

| LNs | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 54.4 | 5 | 18 | 12.3 | <0.001*** |

| T cells | CD3+ | 35.7 | 4.2 | 59.5 | 11.4 | 0.018* |

| Macrophages | F4/80+ | 4.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 0.12 |

| DCs | CD11c+ | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.872 |

| Blood | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 24.6 | 4.2 | 7.6 | 1.9 | <0.001*** |

| Peritoneal cells | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 49.2 | 10.8 | 11.4 | 5 | <0.001*** |

| Mast cells | Ckithigh ST2high | 1.8 | 0.8 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 0.061 |

| Thymus | ||||||

| Double-positive T cells | CD4+ CD8+ | 78.8 | 4.3 | 81.5 | 5.7 | 0.289 |

| CD4+ T cells | CD4+ CD8− | 13.7 | 2.8 | 11.5 | 3.6 | 0.193 |

| CD8+ T cells | CD4− CD8+ | 3.4 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.582 |

| Double-negative T cells | CD4− CD8− | 4.2 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 0.54 |

Cells from six mice of each genotype were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the proportions of the indicated cell populations, which are shown as the percentage of viable cells (PI−). Results are listed as mean ± SD. ***, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

Table 2.

B cell subsets in different lymphatic tissues, blood and peritoneal cells of wild-type and SPPL2a-deficient mice

| Cell type | SPPL2a+/+ | SPPL2a−/− | P-value | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| BM (% of viable cells) | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 21.4 | 6.1 | 15.3 | 2.5 | 0.031* |

| Pro– /pre–B cells | B220+ IgM− | 8.5 | 1.9 | 10.3 | 2 | 0.099 |

| Immature B cells | B220+ IgM+ | 3.6 | 1.9 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 0.694 |

| Recirculating B cells | B220high | 8.6 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 0.2 | <0.001*** |

| Spleen (% of viable cells) | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 45.6 | 6.6 | 23.9 | 13.1 | <0.001*** |

| T1 transitional | B220+ CD21low CD24high | 7.5 | 0.7 | 8.2 | 4.9 | 0.785 |

| T2 transitional | B220+ CD21high CD24high | 11.2 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | <0.001*** |

| Mature B cells | B220+ CD21low CD24low | 23.9 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 4.4 | 0.007** |

| Spleen (×106 splenocytes) | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 33.3 | 13.5 | 4.2 | 2.2 | 0.021* |

| T1 transitional | B220+ CD21low CD24high | 5.2 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.056 |

| T2 transitional | B220+ CD21high CD24high | 7.9 | 2.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.013* |

| Mature B cells | B220+ CD21low CD24low | 17.8 | 7.3 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 0.021* |

| Peritoneal cells (% of viable cells) | ||||||

| B cells | B220+ CD19+ | 49.2 | 10.8 | 11.4 | 5.0 | <0.001*** |

| B1 | B220neg/low CD19high | 34.2 | 13.8 | 6.7 | 4.7 | <0.001*** |

| B2 | B220high CD19+/low | 15.1 | 6.9 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.001** |

Cells of each genotype were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the indicated cell populations as percentage of viable cells (PI−) or absolute cell numbers, respectively. BM, n = 7; spleen, n = 9; blood, n = 6; LNs n = 5; peritoneal cells, n = 12. Results are shown as mean ± SD. ***, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

The frequency of pre- and intermediate stages of B cells in the BM of SPPL2a−/− mice was unchanged up to the immature B cell stage (Fig. 2, F and G, and Table 2). Whereas abundance of transitional T1 cells was not significantly changed in spleens of SPPL2a-deficient (8.2% of PI− cells, 1.8 × 106 splenocytes) versus wild-type mice (7.5% of PI− cells, 5.2 × 106 splenocytes), T2 (0.5 vs. 11.2% of PI− cells, 0.1 vs. 7.9 × 106 splenocytes) and mature B cells (7.0 vs. 23.9% of PI− cells, 1.8 vs. 17.8 × 106 splenocytes) were severely reduced (Fig. 2, F and H, and Table 2) demonstrating that the decrease in B cells becomes apparent after the T1 stage.

Based on the observed B cell maturation block at the T1 stage in SPPL2a−/− mice, we aimed to confirm expression of SPPL2a in the respective B cell subsets. We investigated putative differences in SPPL2a abundance by Western blot analysis of FACS-sorted splenic T1, T2, and mature B cells. SPPL2a was detected in all three populations (Fig. 2 I). However, densitometric quantification and normalization to actin indicated a threefold higher expression of this protease in transitional stage 1 as compared with T2 or mature B cells in two independent experiments. We therefore considered a crucial role of SPPL2a in transitional stage 1 B cells.

B cell maturation pathways and B cell function are impaired in SPPL2a−/− mice

To rule out a role of SPPL2a in stromal cells during B cell development, BM from SPPL2a−/− mice and SPPL2a+/+ controls was transplanted into immunodeficient Rag2−/− cγc−/− mice (Fig. 3 A and Table 3). Recipients of SPPL2a−/− BM developed a B cell phenotype characterized by a significant decrease in splenic transitional T2 cells and mature B cells in the spleen and BM, reminiscent of the findings from SPPL2a−/− mice. Evidently, the B cell maturation defect of SPPL2a−/− mice was passed on to host animals by hematopoietic stem cells, strongly suggesting a cell-intrinsic defect.

Figure 3.

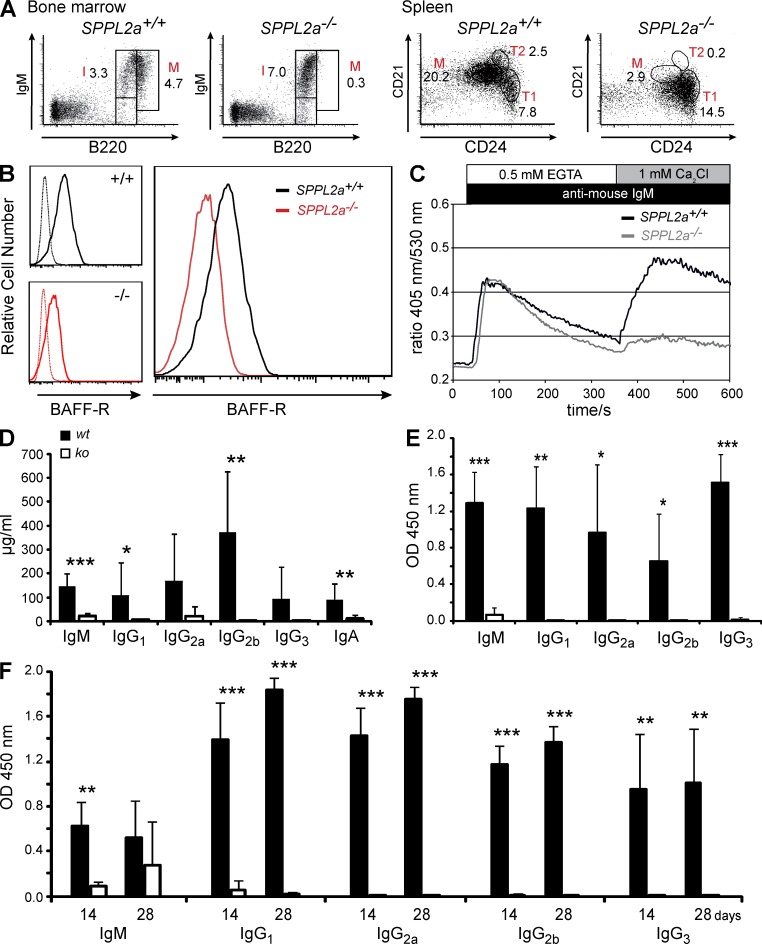

B cell maturation pathways and B cell function are impaired in SPPL2a−/− mice. (A) BM from either wild-type or SPPL2a-deficient mice was transplanted into irradiated Rag2−/− cγc−/− mice. After 10 wk, B cell subsets in BM and spleen were analyzed by co-staining of B220 together with IgM or CD21 and CD24, respectively, and quantified as percentage of viable cells (numbers). Data shown are representative of eight experiments (Table 3). (B) B220+ cells were isolated from spleens of SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− mice and stained for CD21, CD24, and BAFF-R. Histograms show the BAFF-R expression on SPPL2a+/+ (solid line, black) and SPPL2a−/− (solid line, red) T1 B cells (B220+ CD21low CD24high) from a representative of three independent experiments. Specificity of the BAFF-R staining was confirmed by the respective isotype controls (dashed lines). (C) Splenocytes from SPPL2a−/− and wild-type mice were stained for B220, CD21, and CD24 and loaded with the ratiometric Ca2+-sensitive fluorophore Indo-1-AM. After monitoring of basal Ca2+ concentrations in T1 B cells (B220+ CD21low CD24high) for 30 s, cells were stimulated with goat anti–mouse IgM F(ab’)2 fragments and Ca2+ flux was recorded for 5 min in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and for an additional 5 min in the presence of 1 mM extracellular CaCl2. Data are representative of three experiments and were also confirmed in repopulated RAG−/−cγc−/− mice (not depicted). (D) Plasma immunoglobulin levels were measured in wild-type (wt) and SPPL2a−/− mice (ko). Mean ± SD; n = 8–12. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. (E and F) SPPL2a−/− (ko) and wild-type mice (wt) were immunized with the T cell–independent or –dependent antigens TNP-Ficoll (E) or TNP-KLH (F), respectively. Hapten-specific immunoglobulin levels were determined 14 d after antigen application (E and F). For TNP-KLH (F), antigen application was repeated at day 14 and additional serum samples were obtained after an additional 2 wk, at day 28. Results are depicted as mean ± SD; n = 6 per genotype and experimental group, ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test.

Table 3.

B cell populations in RAG2−/−cγc−/− mice 10 wk after transplantation with BM from SPPL2a+/+ or SPPL2a−/− mice

| Cell type | SPPL2a+/+ | SPPL2a−/− | P-value | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| BM (% of viable cells) | |||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 11.8 | 3.3 | 10.9 | 5.3 | 0.694 | |

| Pro– /pre–B cells | B220+ IgM− | 6.2 | 0.6 | 7.7 | 2.5 | 0.136 | |

| Immature B cells | B220+ IgM+ | 6.0 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 1.8 | 0.362 | |

| Recirculating B cells | B220high | 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | <0.001*** | |

| Spleen (% of viable cells) | |||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 41.6 | 1.3 | 20.8 | 6.9 | <0.001*** | |

| T1 transitional | B220+ CD21low CD24high | 6.4 | 1.7 | 11.1 | 3.8 | 0.018* | |

| T2 transitional | B220+ CD21high CD24high | 2.9 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | <0.001*** | |

| Mature B cells | B220+ CD21low CD24low | 24.2 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 2.0 | <0.001*** | |

| T helper cells | CD3+ CD4+ | 10.0 | 2.4 | 14.9 | 3.5 | 0.038* | |

| Cytotoxic T cells | CD3+ CD8+ | 2.5 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 2.7 | 0.004** | |

| Spleen (x106 splenocytes) | |||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 42.5 | 7.9 | 11.3 | 5.2 | <0.001*** | |

| T1 transitional | B220+ CD21low CD24high | 7.3 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 2.4 | 0.300 | |

| T2 transitional | B220+ CD21high CD24high | 3.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | <0.001*** | |

| Mature B cells | B220+ CD21low CD24low | 22.7 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 1.5 | <0.001*** | |

| T helper cells | CD3+ CD4+ | 9.6 | 2.7 | 7.8 | 3.3 | 0.194 | |

| Cytotoxic T cells | CD3+ CD8+ | 2.4 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 0.671 | |

BM from SPPL2a+/+ (n = 8) or SPPL2a−/− (n = 8) mice was transplanted into irradiated RAG2−/−cγc−/− mice. Cells from BM and spleen of host mice were analyzed 10 wk after the transplantation by flow cytometry. Cell populations are expressed as percentage of viable cells (PI−, derived from n = 8) or absolute cell numbers (derived from n = 5), respectively. Data are listed as mean ± SD. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test.

Two pathways are of especially critical importance for promoting further maturation of splenic transitional stage T1 B cells: signals provided by the BCR and by the cytokine BAFF and its three different receptors BAFF-R, TACI, and BCMA (Khan, 2009). We analyzed putative alterations of these pathways that may contribute to the observed developmental block of SPPL2a-deficient B cells at the T1 stage. Because BAFF signals on transitional B cells are mainly transduced by the BAFF-R (Shulga-Morskaya et al., 2004), we examined the surface expression of BAFF-R on SPPL2a−/− T1 B cells in comparison to wild-type T1 cells and observed a significant reduction on the SPPL2a-deficient cells (Fig. 3 B), suggesting that BAFF-encoded survival signals may not be adequately received by those cells. Furthermore, we determined the response to BCR stimulation monitored by cytosolic Ca2+ mobilization. In SPPL2a−/− T1 B cells, especially the Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane was decreased in comparison to wild-type cells (Fig. 3 C). In summary, absence of SPPL2a interferes with two central pathways involved in promoting B cell maturation.

To assess the functional competence of the residual B cells, we determined basal immunoglobulin levels in SPPL2a-deficient and wild-type mice (Fig. 3 D) and performed immunization with T cell–independent (Fig. 3 E) and –dependent (Fig. 3 F) model antigens. Basal immunoglobulin levels were significantly reduced throughout all subclasses in SPPL2a-deficient mice as compared with controls. The antibody response to the T cell–independent antigen trinitrophenol (TNP)-Ficoll was severely impaired in SPPL2a−/− mice, which was shown by only marginal amounts of TNP-specific immunoglobulin being detectable in the sera of these mice (Fig. 3 E). After repeated application of TNP-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) at day 28, TNP-specific IgM reached 50% of wild-type level in SPPL2a−/− mice (Fig. 3 F). Apart from that, only marginal amounts of TNP-specific immunoglobulins were generated by these mice, indicating a significant functional impairment of the remaining B cells in SPPL2a-deficient mice.

SPPL2a−/− B cells accumulate endosomal vacuoles containing CD74 NTF

Thinking of a molecular link between CD74 as a substrate of SPPL2a on the one hand and as the arrest of B cell development in the absence of this protease on the other, two general mechanisms are conceivable. First, generation of the final unstable cleavage product (ICD) that is released into the cytosol will be abolished in SPPL2a−/− B cells, and signals putatively transduced by this molecule will be reduced. At the same time, the CD74 NTF, which is meant to be cleaved by SPPL2a, is accumulating in these cells because of failed turnover at apparently nonphysiological levels (see also Fig. 1 E), and this may perturb cellular processes and homeostasis. If absence of the CD74 ICD were the main mechanism for the observed B cell phenotype in SPPL2a−/− mice, as well as in CD74−/− mice, one would expect highly similar B cell phenotypes in both mice. However, we were intrigued by distinct differences. B cell reduction and functional impairment caused by deficiency of SPPL2a appeared to be significantly more severe than by absence of CD74 (Shachar and Flavell, 1996; Maehr et al., 2004). Furthermore, the developmental arrest becomes apparent at an earlier stage, as CD74−/− mice were reported to possess normal amounts of transitional stage T2 cells (Maehr et al., 2004), which are already significantly reduced in SPPL2a−/− mice.

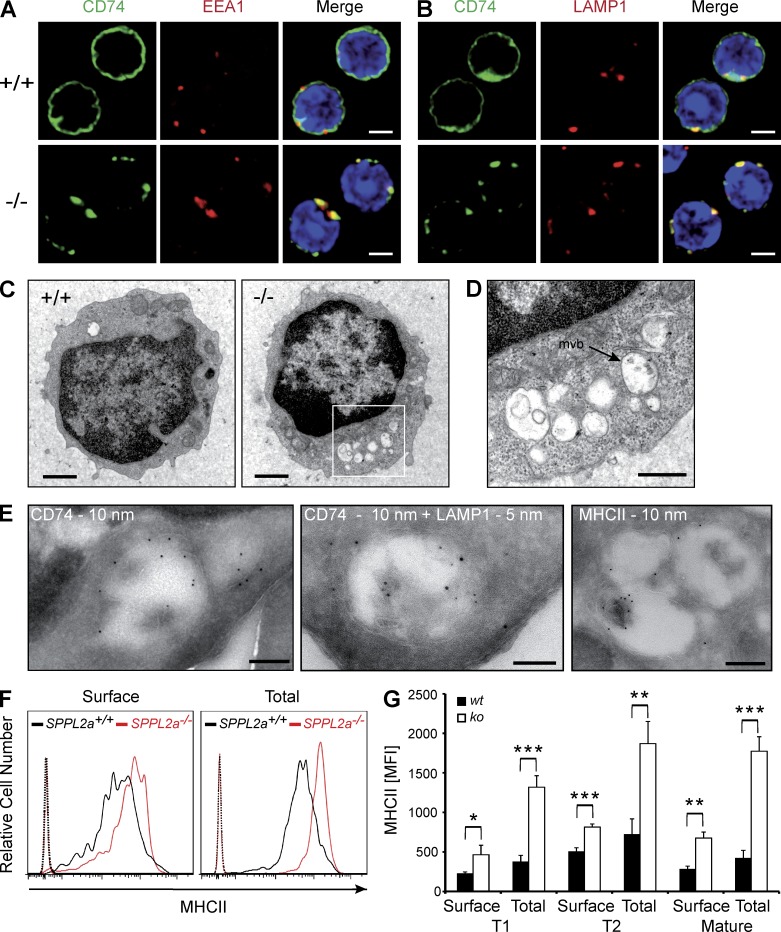

We considered a causative role of the accumulating NTF in the evolution of the B cell defect and analyzed its subcellular localization using an antibody detecting full-length CD74, as well as NTF (Fig. 4, A and B). According to our aforementioned results, the obtained signals in SPPL2a−/− B cells should primarily represent distribution of the NTF and were detected in prominent vesicular structures positive for the early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) and LAMP1, which are markers of early endosomes and lysosomes/late endosomes, respectively. Apparently, the compartments where CD74 NTF accumulates in SPPL2a-deficient B cells are derived from the endocytic pathway, which is in agreement with the general concept of MHCII trafficking and degradation of CD74 by endosomal/lysosomal proteases.

Figure 4.

Disturbance of membrane traffic within the endocytic system of SPPL2a−/− B cells. (A and B) Visualization of CD74 in isolated splenic SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− B cells by indirect immunofluorescence using an antibody against an N-terminal epitope detecting the NTF and the full-length protein. EEA1 (A) and LAMP1 (B) served as markers of early endosomes and lysosomes/late endosomes, respectively. Bars, 2 µm. (C) Transmission electron microscopy of splenic IgM+ B cells from wild-type or SPPL2a−/− mice. Bars, 1 µm. (D) Vacuoles in SPPL2a−/− B cells exhibited various contents of low-electron density. Occasionally, multivesicular bodies (mvb) were observed (arrow). Bar, 500 nm. (E) Presence of CD74 NTF, LAMP1, and MHCII in vacuoles of IgM+ B cells from SPPL2a−/− mice was assessed by immunogold labeling. Bars, 200 nm (CD74 and MHCII single labeling) or 100 nm (CD74 + LAMP1 double labeling). (F and G) Surface and total MHCII levels in transitional stage T1 B cells (B220+ CD21low CD24high) of SPPL2a-deficient or wild-type mice. Splenocytes were stained for B220, CD21, and CD24, allowing for identification of B cell subsets. Subsequently, cells were incubated with anti-MHCII with or without previous permeabilization and analyzed by flow cytometry. Surface and total MHCII levels are shown as histograms representative of three independent experiments or as mean of median fluorescence intensity (MFI) from three mice per genotype (G). ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test.

To assess any major structural alterations of the B cells induced by the persistence of the CD74 NTF, we examined IgM+ splenic SPPL2a−/− B cells by transmission electron microscopy. In these cells, we observed abundant vacuoles that were not detectable at this frequency in wild-type B cells (Fig. 4 C). Many of them exhibited either amorphous, weakly electron-dense luminal contents or intraluminal vesicles and only rarely lamellar structures (Fig. 4 D). Immunogold labeling was used to confirm that these conspicuous vacuoles contain CD74 (Fig. 4 E), as well as the lysosomal/late endosomal marker protein LAMP1 (Fig. 4 E) and MHCII (Fig. 4 E), demonstrating that they are the ultrastructural correlate of the prominent CD74-positive vesicles visualized by immunofluorescence. In conclusion, membrane trafficking within the endocytic system seems to be significantly disturbed in SPPL2a-deficient B cells. As CD74 has been implicated in the regulation of endosome maturation (Lagaudrière-Gesbert et al., 2002; Nordeng et al., 2002; Gregers et al., 2003; Landsverk et al., 2009, 2011) and the observed vacuoles contain CD74 NTF, a causal connection between the NTF accumulation and the morphological changes is strongly suggested.

We assessed whether the disturbed endosomal membrane traffic has any consequences for MHCII homeostasis by flow cytometric analysis of total and surface MHCII expression in splenic SPPL2a-deficient B cells (Fig. 4, F and G). Throughout all developmental stages analyzed (T1, T2, and mature B cells), SPPL2a−/− B cells exhibited significantly increased MHCII levels at the cell surface, which was even more pronounced in total after permeabilization. This was also observed by Western blotting (Fig. 1 E).

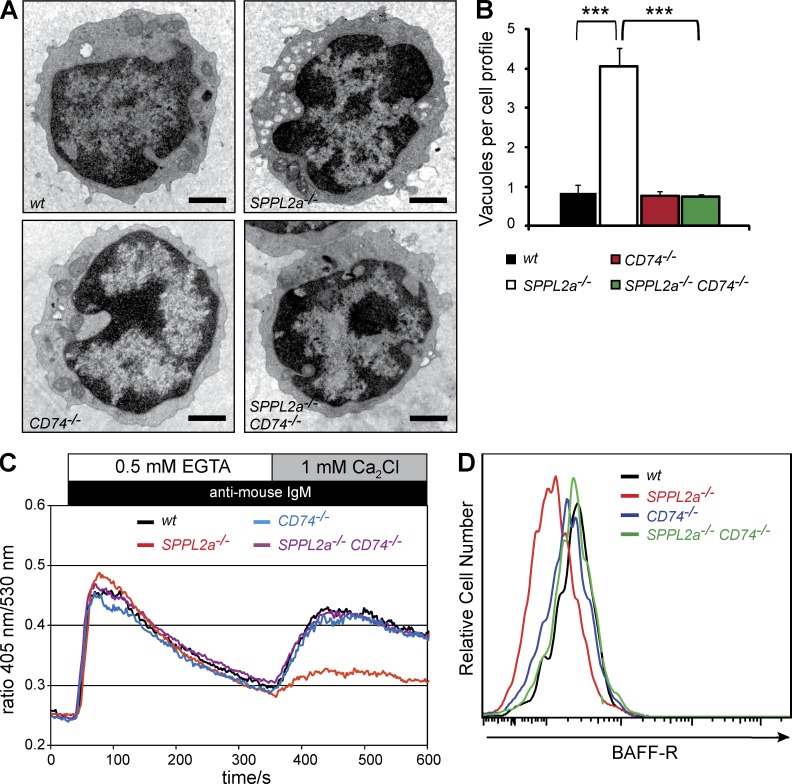

Changes in ultrastructure and signaling in SPPL2a−/− B cells are secondary to CD74 NTF accumulation

Following the hypothesis that the CD74 NTF accumulation rather than the missing ICD directly or indirectly causes the described changes on the cellular level, as well as impaired maturation of SPPL2a−/− B cells, additional genetic ablation of CD74 in the SPPL2a-deficient mice should preclude NTF accumulation and result in a significant alleviation of the phenotype. We tested this by generating SPPL2a-CD74 double-deficient mice. On the level of ultrastructure, SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− splenic IgM+ B cells were indistinguishable from corresponding wild-type and CD74−/− cells (Fig. 5 A), as demonstrated by the mean number of vacuoles per cell (Fig. 5 B). This provides clear evidence that the undegraded CD74 NTF is responsible for the structural changes of endosomal compartments and the perturbation of membrane trafficking. Furthermore, the reduced surface expression of the BAFF-R and the attenuated BCR-induced Ca2+ flux that has been observed in SPPL2a−/− T1 B cells were also completely restored to the level of wild-type cells in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− T1 B cells (Fig. 5, C and D), and should therefore be regarded as secondary events caused by the NTF accumulation.

Figure 5.

Ablation of CD74 restores morphological changes and cellular signaling in SPPL2a−/− B cells. (A) Representative cross sections of splenic IgM+ wild-type, SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− B cells. Bars, 1 µm. (B) Quantification (mean number ± SD) of endosomal vacuoles (diam ≥250 nm) per cellular profile in splenic IgM+ B cells from wild-type, SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice (n = 3–6 mice per genotype, quantification based on 50 cells per specimen). ***, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. (C) Splenocytes from SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, SPPL2a−/− CD74−/−, and wild-type mice were stained for B220, CD21, and CD24 and loaded with the ratiometric Ca2+-sensitive fluorophore Indo-1-AM. In transitional stage T1 B cells (B220+ CD21low CD24high), the basal Ca2+ flux was monitored for 30 s before cells were stimulated with goat anti–mouse IgM F(ab’)2 fragments and Ca2+ flux was recorded for 5 min in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, and for an additional 5 min in the presence of 1 mM extracellular CaCl2. Data are representative of three experiments. (D) BAFF-R surface expression was determined on T1 B cells (B220+ CD21low CD24high) of SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, SPPL2a−/− CD74−/−, and wild-type mice by co-staining isolated splenic B220+ cells for CD21, CD24, and BAFF-R. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

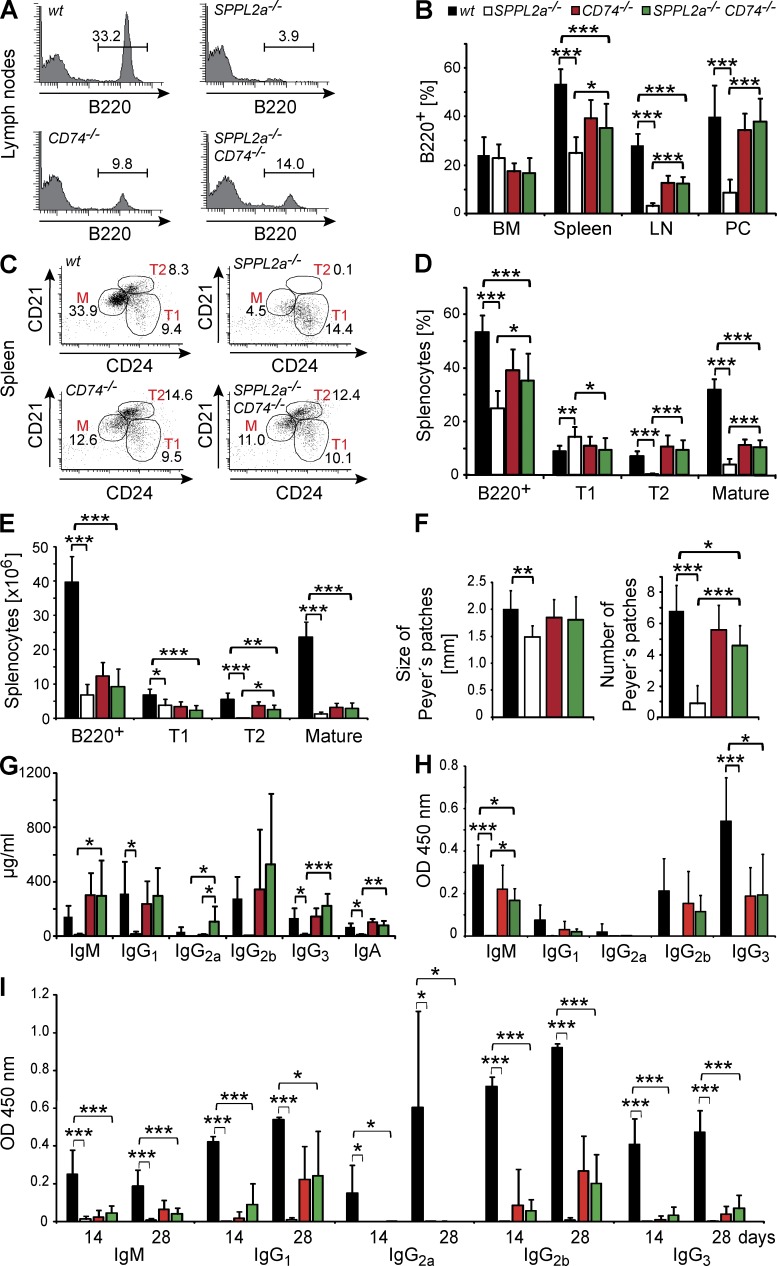

B cell maturation and survival is significantly restored in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice

We evaluated whether the recovery of cellular signaling in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− B cells was reflected in enhanced B cell survival and improved function. SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice exhibited significantly increased total B cells in LNs (12.4 vs. 3.1% of PI− cells) and the peritoneal cavity (38 vs. 8.5% of PI− cells) as compared with SPPL2a−/− mice (Fig. 6, A and B, and Table 4). In the spleen, transitional stage T2 B cells (7.9 vs. 0.5% of PI− cells, 2.6 vs. 0.03 × 106 splenocytes) were present in significantly higher amounts in the double-deficient animals (Fig. 6, C–E, and Table 4) as compared with SPPL2a-deficient mice. However, because CD74 deficiency itself is associated with a reduction of B cells (Shachar and Flavell, 1996), the B cell maturation in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− was not completely restored to the wild-type situation, but merely to that of CD74−/− mice, which was considerably ameliorated compared with SPPL2a−/− mice (Fig. 6, A–E, and Table 4). In agreement, mean size and abundance of Peyer’s patches were also significantly recovered in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice (Fig. 6 F), and basal immunoglobulin levels, which were drastically reduced in SPPL2a−/− mice, were significantly higher in SPPL2a-CD74 double-deficient mice and comparable to those of CD74-deficient and wild-type mice (Fig. 6 G).

Figure 6.

Recovery of B cell development and function by CD74 ablation identifies the accumulating NTF as the primary cause of B cell impairment in SPPL2a−/− mice. (A and B) The frequency of B cells (B220+, % of PI− cells) in BM, spleen, blood, LNs, and the peritoneal cavity (PC) of wild-type, SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice was determined by flow cytometry. Mean ± SD; n = 6 (BM, LN, and PC) or n = 12 (spleen). (C–E) Splenic B cell subpopulations (Total B220+, transitional stage T1, transitional T2, and mature B cells) were determined in wild-type, SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice based on B220, CD21, and CD24 staining, and are depicted as the percentage of living cells (PI−; C and D) or as absolute cell number (E) shown here from 1 representative of 12 experiments (C) or as mean ± SD (D and E) derived from n = 12 (D) or n = 6 (E) mice per genotype. Plots display B220+ cells (C), with numbers indicating the percentage of living cells of the respective populations. (F) Number per animal and mean diameter of Peyer’s patches were determined in wild-type, SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice. Mean ± SD; n = 6. (G) Basal plasma immunoglobulin concentrations of SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice (mean ± SD; n = 6). (H and I) Wild-type (wt), SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/− and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice were immunized with the T cell–independent or –dependent antigens TNP-Ficoll (H) or TNP-KLH (I), respectively. Hapten-specific immunoglobulin levels were determined 14 d after antigen application (H and I). For TNP-KLH (I) a second dose of antigen was administered at day 14, and additional serum samples were obtained at day 28. Mean ± SD; n = 5. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc testing was performed, and significance of wild-type versus SPPL2a−/−, wild-type versus SPPL2a−/− CD74−/−, SPPL2a−/− versus SPPL2a−/− CD74−/−, and CD74−/− versus SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice is depicted.

Table 4.

B cell deficiency of SPPL2a−/− mice was recovered to a significant degree in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice

| Cell type | Wild-type | SPPL2a−/− | CD74−/− | SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− | P-value | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | SPPL2a−/−/do-ko | ||

| BM (% of viable cells) | ||||||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 24.0 | 7.7 | 22.8 | 5.9 | 17.4 | 3.5 | 16.7 | 6.3 | ≥0.05 |

| Pro– /pre–B cells | B220+ IgM− | 13.8 | 4.4 | 16.6 | 3.1 | 12.2 | 1.7 | 10.8 | 3.7 | <0.05* |

| Immature B cells | B220+ IgM+ | 3.7 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1.3 | ≥0.05 |

| Recirculating B cells | B220high | 4.7 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.1 | ≥0.05 |

| Spleen (% of viable cells) | ||||||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 53.4 | 6.4 | 25.0 | 6.6 | 39.3 | 7.8 | 35.3 | 10.1 | <0.05* |

| T1 transitional | B220+ CD21low CD24high | 9.0 | 2.2 | 14.3 | 3.9 | 11.1 | 3.3 | 9.5 | 4.4 | <0.05* |

| T2 transitional | B220+ CD21high CD24high | 7.2 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 10.8 | 4.3 | 9.5 | 3.6 | <0.001*** |

| Mature B cells | B220+ CD21low CD24low | 32.0 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 11.3 | 2.0 | 10.4 | 3.0 | <0.001*** |

| Spleen (x106 splenocytes) | ||||||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 39.7 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 3.1 | 12.3 | 4.0 | 9.2 | 5.1 | ≥0.05 |

| T1 transitional | B220+ CD21low CD24high | 6.8 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | ≥0.05 |

| T2 transitional | B220+ CD21high CD24high | 5.5 | 1.9 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.3 | <0.05* |

| Mature B cells | B220+ CD21low CD24low | 23.6 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 1.7 | ≥0.05 |

| LNs (% of viable cells) | ||||||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 28.1 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 12.6 | 3.0 | 12.4 | 2.7 | <0.001*** |

| Peritoneal cells (% of viable cells) | ||||||||||

| B cells | B220+ | 40.1 | 12.8 | 8.5 | 5.6 | 34.5 | 7.0 | 38.0 | 9.4 | <0.001*** |

| B1 | B220neg/low CD19high | 24.5 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 27.2 | 8.8 | 31.8 | 9.1 | <0.001*** |

| B2 | B220high CD19+/low | 15.1 | 5.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 7.4 | 2.6 | <0.01** |

B cell subsets were analyzed by flow cytometry in BM, spleen, LNs, and peritoneal lavage of wild-type, SPPL2a−/−, CD74−/−, and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− (do-ko) mice. Proportions of cell populations are shown as percentage of viable cells (PI−) or absolute cell numbers, respectively. Results represent mean ± SD from n = 6 mice per genotype (BM, absolute number of splenocytes, LNs, and peritoneal cells) or n = 12 mice (spleen, % of viable cells), respectively. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc testing. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

We further assessed the functional competence of B cells by analyzing the antibody response to the T cell–independent and –dependent antigens TNP-Ficoll (Fig. 6 H) and TNP-KLH (Fig. 6 I). In SPPL2a−/− mice, antigen administration elicited only a marginal antibody response, as described above. In contrast, detectable amounts of hapten-specific IgM, IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG3 were produced by SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice. In the case of TNP-Ficoll, levels of TNP-specific IgM generated by SPPL2a-CD74 double-deficient mice were significantly increased as compared with SPPL2a-deficient mice. CD74-deficient mice were reported before to exhibit impaired T cell–independent and –dependent antibody responses (Shachar and Flavell, 1996), which is reflected in the observation that for most subclasses, the hapten-specific immunoglobulin levels detected in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice were still significantly lower than those in wild-type mice. In conclusion, these findings indicate that not only B cell survival but also B cell function is noticeably improved by deletion of CD74 in SPPL2a−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

By identifying SPPL2a as the postulated and long sought intramembrane protease of CD74, we provide the missing mechanistic link for a process that is essential for B cell development, as indicated by previous studies (Matza et al., 2002a,b). Moreover, we have discovered the first in vivo–validated substrate of SPPL2a and present novel insights into the function of this poorly characterized protease. We conclude that RIP of CD74 by SPPL2a is indispensable for B cell development based on the distinct and severe B cell maturation defect in SPPL2a-deficient mice. The significant recovery of this phenotype achieved by additional ablation of CD74 clearly demonstrates that the phenotype can be mainly attributed to failed proteolysis of CD74 in the absence of SPPL2a. Contributions by other, possibly yet to be discovered substrates or nonproteolytic functions of SPPL2a, may not be fully excluded, but seem to be of minor importance in view of these findings. The alleviated phenotype of SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice strongly suggests that the accumulation of the uncleaved CD74 NTF, and not the absence of any cleavage products, is the driving force of the B cell phenotype in SPPL2a−/− mice. Therefore, we would like to propose a novel perspective. According to our data, the major role of CD74 RIP mediated by SPPL2a is to tightly control the level of CD74 NTF produced by the removal of the luminal domain and the CLIP segment and to avoid an accumulation of this fragment. Apparently, this function of SPPL2a cannot be substituted by the multivesicular body pathway or other I-CLIPs of the SPPL family. In light of the severe phenotype caused by the NTF accumulation potential, minor contributions of reduced signaling by the absence of CD74 RIP cleavage products (Matza et al., 2002a,b) to the phenotype of SPPL2a−/− mice may be masked. Therefore, our findings do not necessarily contradict the previously suggested model of signal transduction by the CD74 ICD, as discussed in this issue of the JEM by Beisner et al. and Bergmann et al. It is conceivable that this mechanism accounts for the residual phenotype of the SPPL2a-CD74 double-deficient mice that perfectly mirrors that of CD74-deficient mice.

Multiple studies have revealed possible functions of CD74 for the regulation of endocytic trafficking (Lagaudrière-Gesbert et al., 2002; Nordeng et al., 2002; Gregers et al., 2003; Landsverk et al., 2009, 2011). In overexpression systems, CD74 was shown to induce formation of giant endosome-derived vacuoles by promoting endosomal fusion, to delay maturation of endosomal compartments, and to modulate the processing and degradation of internalized antigens. The cytoplasmic N-terminal tail has been identified as the critical determinant of CD74 mediating these effects (Nordeng et al., 2002; Gregers et al., 2003). Interaction of this domain with the uncoating ATPase Hsc70 has been suggested to represent the molecular mechanism (Lagaudrière-Gesbert et al., 2002). The structural alterations of the endocytic system observed upon CD74 NTF accumulation in SPPL2a−/− B cells agree well with these studies and provide in vivo confirmation for the potential of CD74 to modulate membrane traffic in the endocytic system as reported already for cathepsin S–deficient cells (Boes et al., 2005).

The phenotype of SPPL2a−/− mice shows intriguing similarity to that of mice deficient either for the cytokine BAFF (Schiemann et al., 2001) or its receptor, BAFF-R (Shulga-Morskaya et al., 2004), regarding the loss of mature B cells and the developmental arrest at the T1 stage. Conspicuously, SPPL2a-deficient T1 B cells show a reduced level of BAFF-R surface expression as compared with corresponding wild-type cells. Apparently, this was secondary to the accumulation of CD74 NTF as it was reversed in SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− B cells. It is tempting to speculate that the impaired transduction of BAFF-mediated survival signals due to reduced receptor levels may represent an important part of the mechanism linking accumulation of uncleaved CD74 NTF with compromised B cell maturation. However, the functional deficits of residual B cells in BAFF-R−/− mice completely lacking the BAFF-R seem to be slightly less pronounced than in SPPL2a−/− mice, which is reflected in preserved antibody responses to the T cell−independent antigen TNP-Ficoll (Shulga-Morskaya et al., 2004). It may be interesting to analyze if changes of surface expression on SPPL2a−/− B cells are also detectable for other receptors of BAFF-like TACI and BCMA (Rickert et al., 2011). TACI−/− mice do not show a depletion of mature B cells, B1 and marginal zone B cells, but were reported to demonstrate impaired responses to T cell–independent antigens caused by a reduced responsiveness of these cells (von Bülow et al., 2001; Yan et al., 2001). Therefore, it is conceivable that the severe functional deficits of the remaining B cells in SPPL2a−/− mice may be related to additional changes in other BAFF receptors, like TACI, and associated downstream signaling pathways. However, we have determined BAFF serum levels in SPPL2a−/− mice in comparison to wild-type mice and found them to be significantly increased (97.5 ± 39.6 ng/ml vs. 4.2 ± 4.4 ng/ml; P < 0.001). Elevated BAFF levels as a consequence of B cell deficiency have been reported before (Kreuzaler et al., 2012), and therefore presumably reflect the diminished B cell compartment in SPPL2a−/− mice. Apparently, BAFF levels increased by 20-fold are not able to overcome the B cell maturation defect, rendering it unlikely that reduced BAFF-R surface expression as well as putative changes to additional BAFF-Rs, like TACI and BCMA (not analyzed), are exclusively responsible for the severe phenotype.

Therefore, additional effects might be exerted by the CD74 NTF accumulation and contribute to the described phenotype of SPPL2a-deficient B cells. This interpretation is supported by our finding that BCR-induced Ca2+ mobilization is also attenuated in SPPL2a−/− B cells, a pathway that has been shown to control cell fate decisions in B cells (Engelke et al., 2007). Hence, the altered Ca2+ signals might account, at least in part, for the observed B cell maturation arrest.

The CD74 NTF, that is observed in SPPL2a−/− B cells, has been proteolytically separated from the CLIP segment by cathepsin S (Nakagawa et al., 1999). Because CLIP represents the major binding site between CD74 and MHCII, no significant direct effects of this NTF on MHCII trafficking and peptide loading would be expected in contrast to those reported in the absence of cathepsin S (Driessen et al., 1999). Therefore, we were intrigued to detect a considerable increase of surface and, even more pronounced, total MHCII levels in SPPL2a−/− B cells. Apart from the CLIP segment, additional interaction sites between CD74 and MHCII were demonstrated to involve the transmembrane segment of CD74 (Castellino et al., 2001), which would be preserved in the accumulating NTF. Based on these findings, weak interactions between the CD74 NTF and MHCII may take place in SPPL2a−/− B cells. These intereactions may, in sum, exert biologically relevant effects on MHCII, considering the massive amounts of accumulating NTF in comparison to CD74 levels in wild-type B cells. Trafficking and turnover of MHCII was shown to be controlled by ubiquitination by the ubiquitin ligase MARCH I in DCs, as well as in B cells (Ma et al., 2012; De Gassart et al., 2008). In DCs, degradation of CD74 was found to be a prerequisite for MHCII ubiquitination (van Niel et al., 2006). Thus, it may be speculated that the CD74 NTF accumulating in SPPL2a-deficient B cells interferes with MHCII ubiquitination and, consecutively, its turnover accounting for the increased levels of MHCII in these cells.

Different explanations have been suggested for the aforementioned B cell deficiency and maturation block observed in CD74-deficient mice. This phenotype was found to be completely resolved when these mice were bred into an MHCII-deficient background (Maehr et al., 2004). This study clearly demonstrated that both CD74 and MHCII are dispensable for B cell maturation and that MHCII plays a decisive role in the emergence of B cell developmental arrest in CD74−/− mice. Similar to ablation of CD74, the knockout of individual chains of MHCII was reported to lead to B cell deficiency (Labrecque et al., 1999), indicating that dysregulations of MHCII homeostasis may be capable of negatively affecting B cell survival. Thus, further studies will be required to analyze the mechanisms, including the disturbed endosomal trafficking induced by CD74 NTF that lead to increased MHCII levels in SPPL2a−/− B cells and the putative consequences this may have on cellular homeostasis and B cell maturation. These aspects may be dissected in the future by studying the effects of MHCII ablation on the B cell phenotypes of SPPL2a−/− and SPPL2a−/− CD74−/− mice, similar to studies carried out on CD74−/− mice (Maehr et al., 2004).

Because B cells are exceptionally dependent on SPPL2a and SPPL2a−/− mice do not appear to be significantly compromised despite the ubiquitous tissue expression of this enzyme in wild-type mice (Friedmann et al., 2004), SPPL2a may represent a novel pharmacological target to selectively interfere with B cell–driven immune responses, as all mature B cell subsets are similarly affected by absence of SPPL2a. B cells play a well-documented role in the pathogenesis of several autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), myasthenia gravis, and pemphigus vulgaris (Viau and Zouali, 2005; Townsend et al., 2010). Thus, therapeutic strategies targeting B cells have been developed and reviewed over the past few years, the majority of them based on antibodies, e.g., rituximab (Dörner et al., 2009). We suggest that pharmacological inhibition of SPPL2a activity should be evaluated as a potential therapeutic strategy for depleting B cells and modulating humoral immune responses to treat autoimmune disorders. Based on available compounds inhibiting the mechanistically related γ-secretase, the development of potent and specific small-molecule SPPL2a inhibitors may be an attainable goal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

The strategy for targeting of the murine SPPL2a gene by insertion of a neomycin-cassette in exon 2 is illustrated in Fig. 2 A. For generation of the targeting construct, a 5.1-kB fragment surrounding exon 2 of murine SPPL2a (2.3-kb 5′-homology arm and 2.8-kb 3′-homology arm) was amplified from genomic DNA of 129SVJ mice and subcloned in pJET1/blunt (Fermentas). The neomycin expression cassette from pMC1neo (Stratagene) was inserted into exon 2 by overlap-extension PCR so that concomitantly 57 bp of exon 2 sequence were deleted. The fusion PCR product was subcloned into pJET1/blunt. The targeting vector was linearized with XhoI and electroporated into the embryonic stem (ES) cell line R1 (Nagy et al., 1993). G418-resistant colonies were initially screened by PCR for homologous recombination. Positive clones were confirmed by Southern blot analysis after restriction digest of genomic DNA with NdeI. A probe comprising 454 bp of the 5′ upstream region was generated by PCR from genomic DNA. The targeted ES cells were injected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice. Chimeric male offspring was mated with C57BL/6N Crl females.

Mice were genotyped by PCR using SPPL2a-specific primers (forward, 5′-AAACTCATTGAAGGACTTGCTC-3′; reverse, 5′-TTTCTAGGGAACTTGGAAGTC-3′) amplifying PCR products of 242 and 1,323 bp from the wild-type and targeted locus, respectively. In addition, a PCR specifically detecting the neomycin expression cassette (forward, 5′-GTTGTCACTGAAGCGGGAAGGGACTGGCTG-3′; reverse, 5′-GCGAACAGTTCGGCTGGCGCGAGCCCCTGA-3′) with a product of 280 bp was performed (Fig. 2 A). Absence of SPPL2a wild-type transcript was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 2 A). Total RNA was isolated from tissues or murine embryonic fibroblasts with the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel). Reverse transcription was conducted using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas) and random hexamer primers. Primers annealing in exons 1 and 3 of the SPPL2a ORF (forward, 5′-CACTCGCTGCACGCTCCC-3′; reverse, 5′-CACCTTCCTGTGCAATTCTGGCT-3′) were used to amplify a 342-bp fragment of the SPPL2a wild-type transcript from the cDNA. In parallel, appropriate primers for a fragment of β-actin (forward, 5′-GTTACAACTGGGACGACATGG-3′; reverse, 5′-GATGGCTACGTACATGGCTG-3′) were used as a control.

CD74-deficient mice (B6.129S6-Cd74tm1Liz/J) have been described previously (Bikoff et al., 1993) and were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory for breeding with SPPL2a−/− mice to generate SPPL2a-CD74 double-deficient animals. Rag2−/− cγc−/− mice (Goldman et al., 1998) were obtained from Taconic. All experiments were performed with littermates and/or appropriate controls matched for sex and age.

For initial phenotypic analyses of SPPL2a-deficient mice (datasets presented in Figs. 2 and 3 and Tables 1–3) animals on a mixed genetic background (C57BL/6N/129/Sv) were used. Subsequently, SPPL2a−/− mice were backcrossed for 10 generations on a C57BL/6N Crl background and bred with CD74−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) for generation of SPPL2a-CD74 double-deficient mice (datasets depicted in Figs. 5 and 6 and Table 4). Animal experimentation was performed in agreement with the guidelines of the University of Hamburg (acceptance no. 78/07) and the University of Kiel (acceptance no. V 312–72241.121-3 [22–2/10]) for use of animals and their care.

cDNA constructs and siRNA.

Murine CD74 p41 cDNA (clone IRAVp968E041D) was obtained from ImaGenes. Based on this template, two epitope-tagged expression constructs of the shorter and more abundant p31 isoform (HA-mCD74p31-V5 and mCD74p31-HA) were generated by overlap-extension PCR. For this purpose, HA-mCD74-BamHI-Fw (5′-GATCGGATCCACGCCACCATGTACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGCTGATGACCAACGCGACCTCA-3′) and mCD74-V5-XhoI-Rv (5′-GATCCTCGAGTCACGTAGAATCGAGACCGAGGAGAGGGTTAGGGATAGGCTTACCCAGGGTGACTTGACCCAGTTC-3′), or mCD74-BamHI-Fw (5′-GATCGGATCCACGCCACCATGGATGACCAACGCGACCT-3′) and mCD74-HA-XhoI-Rv (5′-GATCCTCGAGTCAAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTACAGGGTGACTTGACCCAGTTC-3′), were used as flanking primers and mCD74-p31-Fw (5′-AGCCCACCGAGGCTCCACCTAAAGAGCCACTGGACATGGAAGACC-3′) in conjunction with mCD74-p31-Rv (5′-GGTCTTCCATGTCCAGTGGCTCTTTAGGTGGAGCCTCGGTGGGCT-3′) were used as internal primers, respectively. PCR products were subcloned into pcDNA3.1/Hygro+ (Invitrogen) after restriction digestion with BamHI and XhoI. For the generation of stably expressing HEK293 Flp-In cells (Invitrogen), the insert HA-mCD74p31-V5 was excised from the respective pcDNA3.1/Hygro+ construct and subcloned into pcDNA5/FRT (Invitrogen).

Cloning of an expression construct of murine SPPL2a with a C-terminally appended myc epitope has been described previously (Behnke et al., 2011). The active site mutant D416A was generated by overlap-extension PCR using mSPPL2a-D416A-Fw (5′-GGTTTCGGAGCAATCATTGTACCAGGCCTGTTG-3′) and mSPPL2a-D416A-Rv (5′-TACAATGATTGCTCCGAAACCCAATACTGAAAC-3′) as internal primers and mSPPL2a-HindIII-Fw (5′-CTGAAAGCTTGCCACCATGGGGCTGCTGCACTCG-3′) and mSPPL2a-Myc-XhoI-Rv (5′-GTTACTCGAGTTACAGATCCTCTTCTGAGATGAGTTTTTGTTCCTGTTGTACAATCTGCTCATCAGTCGTC-3′) as flanking primers, respectively.

Transient down-regulation of human SPPL2a in HEK Flip-In cells was performed with Stealth Select RNAi (Invitrogen) siRNA: HSS131389 (5′-GGGCAACCUGCUCUCCUCUAUUUAG-3′), HSS131390 (5′-GGACCAUUUGGAUUGUGCAACAAAU-3′), and HSS131391 (5′-GAUAUUCCUCCUGUUGGCAUAAAGA-3′). As a control, recommended nontargeting control siRNAs from the same supplier were used.

Cell culture and transfection.

HeLa, HEK293, and HEK293 Flp-In (Invitrogen) cells were maintained in DMEM (PAA) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (PAA), 100 U/ml penicillin (PAA), and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (PAA). All cell lines were transiently transfected at semiconfluence using Turbofect (Fermentas) corresponding to manufacturer’s instructions with 2.5 µg DNA per 10-cm culture dish. To reduce cytotoxicity, the culture medium was replaced by fresh medium 6 h after transfection.

HEK293 cells stably expressing HA-mCD74p31-V5 were generated based on HEK293 Flp-In cells (Invitrogen). Before transfection, HEK293 Flp-In were propagated in the presence of 100 µg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen). Cells were co-transfected with HA-mCD74p31-V5 in pcDNA5/FRT (Invitrogen) and pOG44 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Selection was initiated with 200 µg/ml Hygromycin (PAA) 48 h after transfection. Hygromycin-resistant cells were kept under selection conditions and maintained as a batch without subcloning. Expression of mCD74p31 was validated by Western blotting and indirect immunofluorescence.

A pool of three different siRNAs directed against human SPPL2a, as well as of three nontargeting control siRNAs, were transfected into HEK293 Flp-In cells stably expressing HA-mCD74p31-V5 with INTERFERin (Polyplus transfection) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, with a final concentration of 50 nM siRNA in the culture medium.

For inhibition of proteases, the following reagents were used at the concentration indicated in Fig. 1 B: (Z-LL)2-ketone (Peptanova), leupeptin (Roth), inhibitor X (EMD Millipore), and NH4Cl (Merck).

Protein extraction and immunoblotting.

Cultured cells were harvested by scraping into PBS and cells were sedimented at 1,000 g for 5 min. Pelleted cells were extracted in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 0.1% [wt/vol] SDS, and 4 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease inhibitors as described previously (Schröder et al., 2010). Samples were sonicated (level 4 for 20 s) using a Branson Sonifier 450 (Emerson Industrial Automation) at 4°C and incubated on ice for 1 h. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation (15,000 g for 10 min) and the protein concentration was determined with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

SDS/PAGE (Laemmli, 1970), semidry transfer onto nitrocellulose and immunodetection were performed as described previously (Schröder et al., 2010). For the detection of SPPL2a, the boiling step was omitted and samples were incubated for 5 min at 56°C instead. To improve higher resolution of CD74 NTFs, Tricine-SDS-PAGE (Schägger, 2006) was used along with a separating gel with T = 16% and C = 6% supplemented with 6 M urea. Overnight semidry transfer to nitrocellulose was performed as previously described (Schägger, 2006).

For protein detection on Western Blots, the primary antibodies anti-CD74 (In-1; BD), anti-mSPPL2a (Behnke et al., 2011), a monoclonal anti–human SPPL2a (KLH-6E9-11; provided by R. Fluhrer and E. Kremmer, DZNE, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, Munich, Germany), anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-tubulin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa city, IA), anti–MHC-II (M5/114.15.2; eBioscience), and anti-HA (Roche) were used. The HRP-labeled secondary antibodies goat anti–rabbit, sheep anti–mouse, and goat anti–rat (Dianova) were used followed by detection with Amersham ECL Advance Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare).

Flow cytometric analysis.

To obtain single-cell suspensions, LNs and spleens were cut into pieces and passed through a 100-µm cell strainer suspended in FACS buffer (PBS containing 2% [vol/vol] FBS, 0.1% [wt/vol] NaN3, and 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Red BM was isolated from femur and tibia of hind limbs by flushing the bones with FACS buffer and dissociated by a 100-µm cell strainer. Peritoneal cells were obtained by injecting 7 ml FACS buffer into the murine peritoneal cavity, and cells were dispensed by gentle massage and collected afterward. Lysis of erythrocytes was performed by incubation in 155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM EDTA for 10 min at room temperature.

Cell suspensions were stained for 30 min at 4°C with the following FITC-, PE-, PE/Cy5-, PE/Cy7-, or APC-conjugated murine antibodies: anti-CD3 (145-2C11), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD11c (N418), anti-CD21/CD35 (8D9), anti-CD268 (BAFF-R, 7H22-E16), and anti-CD45R (RA3-6B2; all from eBioscience); anti-CD4 (PJP6), anti-CD8a (YTS 169.4), and anti-CD19 (PeCa1; all from Immunotools); anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD21 (7G6), anti-CD43 (S7), anti-CD117 (Ckit, 2B8), anti-IgD (11-26c.2a), anti-IgM (R6-60.2), anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), and anti-TCRVβ5.1,5.2 (MR9-4; all from BD); anti-CD3 (17A2), anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8a (53–6.7), anti-CD23 (B3B4), anti-CD24 (M1/69), anti-CD49b (DX5), and anti–I-AB MHCII (AF6-120.1; all from BioLegend); anti-F4/80 (CI:A3-1; AbD Serotec); and anti-ST2 (DJ8; mdBiosciences). After washing, stained cells were resuspended in 0.5 µg/ml PI to stain dead cells (PI+).

For analysis of surface MHCII, single-cell suspensions from spleen were obtained as described above without performing lysis of erythrocytes. Cells were stained for 30 min at 4°C with anti-CD21/CD35 (8D9), anti-CD24 (M1/69), and anti-CD45R (RA3-6B2), along with anti-MHCII (M5/114.15.2) from eBioscience in MACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 2 mM EDTA and 0.5% [wt/vol] BSA). To detect total MHCII, anti-MHCII was omitted at this stage, and cells were fixed with 2% PFA in PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% (wt/vol) saponin in PBS containing 5% (vol/vol) FBS and stained with anti-MHCII (M5/114.15.2) for 30 min at 4°C. In both cases, lysis of erythrocytes was performed by incubation in FACS Lysing Solution (BD) for 10 min at room temperature before flow cytometric analysis.

Flow cytometry was performed using a LSRII, FACSCanto, or FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD). Data were analyzed with FACSDiva, CellQuest II (BD) or FlowJo (Tree Star) software.

Isolation of B cells.

For generation of a single cell suspension murine spleens were cut into pieces and passed through a 100-µm cell strainer suspended in MACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 2 mM EDTA and 0.5% [wt/vol] BSA). IgM+ B cells were obtained by positive selection using anti–mouse IgM MicroBeads and LS columns of the MACS cell separation system (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. B cell purity was found to be between 80 and 90% as determined by flow cytometric analysis using anti-CD45R. Similarly, for immunofluorescent staining of B cells, total splenic B cells were recovered from splenocytes using the Pan B cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and LD depletion columns. Splenic B cell subpopulations (T1, T2, and Mature B cells) for analysis of SPPL2a expression by Western blotting were obtained by staining B220+ MACS-isolated splenic B cells with anti-B220, anti-CD21, and anti CD-24 followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting using a FACSAria I (BD).

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

Mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of xylazine/ketamine and perfused with 4% (wt/vol) PFA in PBS. Organs were post-fixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA overnight. Spleens, LNs, or Peyer’s patches were either embedded into Jung Tissue Freezing Medium (Leica) or paraffin and sectioned at 5 µm. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin according to standard protocols. Cryostat sections were boiled for 5 min in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for epitope retrieval and stained with anti-CD45R (RA3-6B2; Immunotools) and anti-CD3 (C7930; Sigma-Aldrich). Alkaline phosphatase labeled anti–rabbit IgG (C7930; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to visualize CD3 antibody binding by NBT-BCIP staining (Sigma-Aldrich). Sensitivity of anti-CD45R staining was enhanced by incubation with biotinylated anti–rat IgG (Vector Laboratories), followed by addition of Streptavidin-HRP (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories). HRP activity was visualized by peroxidase substrate kit DAB (Vector Laboratories). Sections were embedded in 17% Mowiol 4–88 (EMD Millipore), 33% glycerol, and 20 mg/ml DABCO (1,4-diaza-bicyclo-[2,2,2]-octane) in PBS and viewed with an Olympus BX50 microscope (Olympus) equipped with U Plan Fl 4× (N.A. 0.13) or 10× (N.A. 0.30) objectives (Olympus). Images were acquired with an Olympus UC30 digital color camera and Olympus Soft Imaging solutions software and further processed using Adobe Photoshop.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Coverslips were coated in 100 µg/ml poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight and washed twice with water for 1 h before use. Total splenic B cells isolated by negative depletion using the MACS-system were cultured on coated coverslips in RPMI-1640 (PAA; Cölbe) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin (PAA), and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (PAA) for 1.5 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) PFA in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. Immunocytochemical stainings were performed as described previously (Savalas et al., 2011) with anti-CD74 (In-1; BD) or a polyclonal antiserum raised against the N terminus of CD74 (Barois et al., 1997) provided by N. Barois (Institut Pasteur de Lille, Lille, France) and W. Stoorvogel (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands) and anti-EEA1 (clone C45B10; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-LAMP1 (1D4B; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) as primary and Alexa Fluor 488– or 594–conjugated goat anti–rat IgG or goat anti–rabbit IgG as secondary antibodies (MoBiTec), respectively. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides in a medium containing 17% Mowiol 4–88 (EMD Millipore), 33% glycerol, and 20 mg/ml DABCO (1,4-diaza-bicyclo-[2,2,2]-octane) in PBS. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI (4-,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma-Aldrich) added to the embedding medium at a concentration of 1 µg/ml. Photographs of optical sections were acquired with an FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus) equipped with an U Plan S Apo 100× oil immersion objective (N.A. 1.40) and Olympus Fluoview Software (3.0a). For further processing, Adobe Photoshop software was used.

Ultrastructural analysis of IgM+ B cells.

IgM+ B cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting from spleens of SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− mice as described above. For transmission electron microscopy, cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, in suspension for 1 h at 22°C and overnight at 4°C. Fixed B cells were sedimented (220 g for 5 min), incorporated in BSA as previously described (Taupin, 2008), and stored in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer. BSA blocks were postfixed with 2% OsO4 and embedded in araldite according to routine methods. Semithin sections (1 µm) were stained with toluidine blue and ultrathin sections with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. From each specimen, 50 B cells were photographed at a magnification of 7000×. Vacuoles with a diam ≥ 250 nm were counted on the computer screen, and the mean number of vacuoles per cell profile was calculated for each specimen. Data shown are derived from at least three independent replicates per genotype.

For immunoelectron microscopy, B cells were fixed in 2% (wt/vol) PFA and 0.1% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, for 1 h and stored in 2% (wt/vol) PFA in the same buffer for 9 d. The cells were embedded in gelatin, infiltrated in a mixture of sucrose and polyvinylpyrrolidone, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Thin sections were cut at −100°C, picked on grids, and immunogold labeled using rat anti-CD74 (In-1; BD), rat anti–MHC-II (M5/114.15.2; eBioscience), or rabbit anti–LAMP-1 (Y. Tanaka, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan). The primary antibodies were detected using goat anti–rat IgG coupled to 10-nm gold or goat anti–rabbit IgG coupled to 5-nm gold (British Bio Cell). Double labeling was performed using a mixture of rat anti-CD74 and rabbit anti–LAMP-1 antibodies. Finally, the grids were contrasted and embedded in a mixture of methyl cellulose and uranyl acetate.

Determination of basal immunoglobulin levels.

A sandwich ELISA was used for the immunoglobulin isotype determination in serum. 96-well ELISA plates were coated with mouse immunoglobulin isotype-specific antibodies to IgG1 (A85-3), IgG2a (RII-89), IgG2b (R9-91), IgG3 (R2-38), IgA (C10-3), and IgM (CII/41; all from BD Biosciences), and then diluted in 50 mM carbonate buffer, pH 9.6. After overnight incubation at 4°C plates were blocked with 1% (wt/vol) BSA in PBS supplemented with 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween-20 for 1 h and serum samples were diluted in duplicates. Plates were incubated either with biotinylated anti-κ (187.1) and anti-λ (R26-46) antibodies, or biotinylated anti-IgG1 (A85-1), anti-IgG2a (R19-15) anti-IgG2b (R12-3) or anti-IgG3 (R40-82; all from BD) for 3 h, washed, and incubated with HRP-labeled streptavidin (EMD Millipore). Alternatively, Clonotyping System-HRP (5300–05; Southern Biotech) was used for isotype-specific determination of immunoglobulins according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To calculate immunoglobulin concentrations, purified mouse immunoglobulins (BD) were diluted on each plate as a standard. For the colorimetric detection either o-phenylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich) or BM Blue POD Substrate (Roche) was used as a substrate. Absorbance was measured at 482 or 450 nm, respectively, in a microplate reader (Synergy HT or Powerwave 340; BioTek Instruments).

Immunization and antibody responses.

T cell–independent immune response was analyzed by i.p. immunization with TNP-AECM-Ficoll (Biosearch Technologies). At day 0, blood was taken from the caudal vein. Mice were immunized with 100 µg TNP-Ficoll dissolved in 100 µl PBS. At day 14, blood samples were analyzed for TNP-specific antibodies.

For T cell–dependent immune response analysis, mice were bled and immunized with 100 µg TNP-KLH (Biosearch Technologies) in PBS supplemented with 50% (vol/vol) complete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final volume of 100 µl. At day 14, booster immunization with 100 µg TNP-KLH in 100 µl PBS supplemented with 50% (vol/vol) incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich) was performed. At day 28, mice were sacrificed and the blood was analyzed.

For determination of TNP-specific antibodies, 96-well ELISA plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with 10 µg/ml TNP-ovalbumin (Biosearch Technologies) in PBS at 4°C overnight, washed, and blocked with 1% (wt/vol) casein in PBS. Different dilutions of serum were added to the plates and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, isotype specific HRP-conjugated goat anti–mouse immunoglobulin antibodies (5300–05; Southern Biotech) were added for 1 h at room temperature. BM Blue POD Substrate (Roche) was used for detection.

Analysis of B cell receptor signaling.

For analysis of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, splenocytes were stained with anti–CD45R-PE-Cy7, anti–CD21-FITC, and anti–CD24-PE (BD) and subsequently loaded for 25 min at 30°C with 1 µM Indo-1-AM (Invitrogen) in RPMI medium containing 5% (vol/vol) FBS and 0.015% Pluronic F127 (Invitrogen) under mild agitation. Cells were diluted 1:1 with RPMI containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS and incubated for 10 min 37°C before being washed with and resuspended in Kreb’s Ringer solution, composed of 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.0, 140 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose plus 0.5 mM EGTA. After basal Ca2+ concentrations were monitored, cells were stimulated with 10 µg/ml goat anti–mouse IgM immunoglobulin F(ab’)2 fragments from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. After 6 min, CaCl2 was added to achieve an extracellular Ca2+ concentration of 1 mM. The fluorescence ratio of Ca2+-bound Indo-1 (405 nm) to Ca2+-unbound Indo-1 (530 nm) was monitored on an LSRII cytometer (BD) and data were processed with FlowJo (Tree Star).

BM transplantations.

BM cell suspensions were isolated from SPPL2a+/+ and SPPL2a−/− mice. 107 BM cells (containing on average <2% CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) were intravenously injected into irradiated (9 Gy) Rag2−/− cγc−/− mice devoid of B, T, and NK cells. 6 wk after transplantation, peripheral blood was collected and analyzed by flow cytometry for reconstitution with B cells, T lymphocytes, and NK cells. 10 wk after transplantation, the animals were sacrificed to analyze spleens, BM, and thymi.

Statistics.

Data are shown as means ± SD. For statistical analyses, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc testing was used, as indicated. Significance levels of P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), and P < 0.001 (***) were applied.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marlies Rusch, Sebastian Held, Dagmar Niemeier, Rafael Kurz, Leslie Elsner, Gabi Sonntag, Katrin Westphal and Katrin Streeck for excellent technical assistance, Nur Güneli for conducting related experimental work and Markus Herrmann, Department Radiotherapy and Radiation Oncology, University of Göttingen, for irradiation of mice. We thank Zane Orinska, Department of Immunology and Cell Biology, Research Center Borstel, for help with initial immunological phenotyping of SPPL2a-deficient mice, Hans-Heinrich Oberg and Sandra Ussat, Immunological institute, University of Kiel, for help with flow cytometric sorting of splenic B cells and the Electron Microscopy Unit of the Institute of Biotechnology, University of Helsinki for providing laboratory facilities. Furthermore, we thank Willem Stoorvogel, Utrecht university, and Nicolas Barois for sharing a polyclonal antibody against CD74.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft as part of the SFB 877 and the Centre of Excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces”.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- BCR

- B cell antigen receptor

- BMDC

- BM-derived DC

- CLIP

- class II-associated li chain peptide

- EEA1

- early endosome antigen 1

- ICD

- intracellular domain

- I-CLIP

- intramembrane-cleaving protease

- KLH

- keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MHCII

- MHC class II complex

- NTF

- N-terminal fragment

- PI

- propidium iodide

- RIP

- regulated intramembrane proteolysis

- SPPL2a

- signal-peptide-peptidase-like 2a

- TNP

- trinitrophenol

References

- Barois N., Forquet F., Davoust J. 1997. Selective modulation of the major histocompatibility complex class II antigen presentation pathway following B cell receptor ligation and protein kinase C activation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3641–3647 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Herman S., Arie G., Medvedovsky H., Kerem A., Shachar I. 2005. CD74 is a member of the regulated intramembrane proteolysis-processed protein family. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:5061–5069 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke J., Schneppenheim J., Koch-Nolte F., Haag F., Saftig P., Schröder B. 2011. Signal-peptide-peptidase-like 2a (SPPL2a) is targeted to lysosomes/late endosomes by a tyrosine motif in its C-terminal tail. FEBS Lett. 585:2951–2957 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisner D.R., Langerak P., Parker A.E., Dahlberg C., Otero F.J., Sutton S.E., Poirot L., Barnes W., Young M.A., Niessen S., et al. 2013. The intramembrane protease Sppl2a is required for B cell and DC development and survival via cleavage of the invariant chain. J. Exp. Med. 210:23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann H., Yabas M., Short A., Miosge L., Barthel N., Teh C.E., Roots C.M., Bull K., Jeelall Y., Horikawa K., et al. 2012. B cell survival, surface BCR and BAFFR expression, CD74 metabolism, and CD82 dendritic cells require the intramembrane endopeptidase SPPL2A. J. Exp. Med. 210:31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikoff E.K., Huang L.Y., Episkopou V., van Meerwijk J., Germain R.N., Robertson E.J. 1993. Defective major histocompatibility complex class II assembly, transport, peptide acquisition, and CD4+ T cell selection in mice lacking invariant chain expression. J. Exp. Med. 177:1699–1712 10.1084/jem.177.6.1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes M., van der Wel N., Peperzak V., Kim Y.M., Peters P.J., Ploegh H. 2005. In vivo control of endosomal architecture by class II-associated invariant chain and cathepsin S. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:2552–2562 10.1002/eji.200526323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.S., Goldstein J.L. 1997. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 89:331–340 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80213-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]