Abstract

Background

The PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] mutation has been reported in at least three breast cancer families and breast cancer cases of French Canadian descent and this has been attributed to common ancestors. The number of mutation-positive cases reported varied based on criteria of ascertainment of index cases tested. Although inherited PALB2 mutations are associated with increased risks of developing breast cancer, risk to ovarian cancer has not been fully explored in this demographically unique population.

Methods

We screened the PALB2 p.Q775X variant in 71 families with at least three cases of breast cancer (n=48) or breast and ovarian cancers (n=23) that have previously been found negative for at least the most common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations reported in the French Canadian population and in 491 women of French Canadian descent who had invasive ovarian cancer and/or low malignant potential tumors of the major histopathological subtypes.

Results

We identified a PALB2 p.Q775X carrier in a breast cancer family, who had invasive ductal breast carcinomas at 39 and 42 years of age. We also identified a PALB2 p.Q775X carrier who had papillary serous ovarian cystadenocarcinoma at age 58 among the 238 serous subtype ovarian cancer cases investigated, who also had breast cancer at age 52.

Conclusion

Our findings, taken together with previous reports, support adding PALB2 c.2323C>T p.Q775X to the list of cancer susceptibility genes for which founder mutations have been identified in the French Canadian population.

Keywords: PALB2, p.Q775X, p.Q775*, Hereditary breast cancer, Breast cancer risk, Ovarian cancer, Founder mutations, French Canadians

Background

Carriers of PALB2 mutations in a heterozygous state have been associated with increasing the risk of developing breast cancer [1-10]. PALB2 is a partner and localizer of the BRCA2 breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility protein to DNA damage sites [9,11]. Penetrance estimation for conferring breast cancer risk has been hampered by the paucity of cases, although estimates of 2- to 6-fold increased risk to breast cancer have been suggested [12,13], thus classifying PALB2 as a moderate breast cancer risk allele [9,12-14]. Germline mutations in PALB2 have also been identified in familial pancreatic cancer [15,16]. PALB2 is comprised of 13 exons spanning a 38 kb region on chromosome 16p12.1 and mutation screening is complicated by the diversity of variants (including missense mutations) identified in cancer cases. The PALB2 c.2323C>T mutation, which results in the introduction of a stop codon at amino acid position 775 (p.Q775X), has been reported in at least three French Canadian breast cancer families [5], and along with other protein truncating PALB2 mutations found in breast cancer cases, is strongly suspected to be deleterious [17]. The French Canadian population of Quebec exhibits an unique genetic demography [18-20]. About 40% of French Canadian cancer families with at least three cases of breast and/ovarian cancer carry a pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation [20-25]. Although 15 different mutations in these genes have been reported in French Canadian cancer families, six specific mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been shown to account for a significant majority of mutation-positive families [20-26]. This has been attributed to a shared ancestry of mutation carriers due to common founders of the French Canadian population of Quebec [25-28].

The number of PALB2 p.Q775X mutation-positive cases that have been reported thus far in studies involving the French Canadian population vary according to criteria and catchment area of ascertainment of index breast cases tested [5,29]. To further assess the contribution of PALB2 p.Q775X mutation in the French Canadian population, we report the results of screening this variant in 71 well defined cancer families with at least three confirmed cases of breast and/ovarian cancer found negative for the most common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation reported in this population. We report the cancer phenotype of a new p.Q775X mutation-positive family. We also report the screening 385 invasive ovarian cancer cases and 106 low malignancy potential ovarian tumors not selected for family history of cancer that were ascertained from the French Canadian population, and describe the cancer history of the p.Q775X cases identified in this screen. We describe our findings in the context of previous studies describing mutation screens of PALB2 in individuals of French Canadian descent.

Methods

Subjects and cancer families

The study subjects fall within two defined groups. The first group contains index cases from 71 independently ascertained families (Table 1). The index cases tested for mutations were recruited to the study through the hereditary cancer clinics in Montreal as part of research studies assessing the contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast and/or ovarian cancer families as described previously [21,25]. They have a family history of breast cancer (n= 48) or breast and ovarian cancer (n=23) according to the following criteria: in addition to the index case affected with breast cancer at less than 66 years of age, the families contained at least two other confirmed cases of invasive breast and/or epithelial ovarian cancer in the same familial branch. The affected index cases from 26 breast cancer families (HBC) and 14 breast-ovarian cancer (HBOC) families were previously screened and found negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequence variants by commercial DNA sequencing (Myriad Genetics, Myriad Genetics Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT, USA). The index affected cases from the remaining 22 HBC and 9 HBOC families were found negative for 20 BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations reported in French Canadian cancer families of Quebec which include the following most common BRCA1 (c.4327C>T (R1443X), c.2834_2836delGTAinsC) and BRCA2 (c.8537_8538delAG, c.5857G>T (E1953X), c.3167_3171delAAAAG) mutations reported in this population, as described previously [22,23,25]. All index cases in this study self-reported grandparental French Canadian ancestry. The second group contained 385 females with epithelial ovarian carcinomas and 106 low malignant potential tumors (Table 2), who were recruited to Banque de tissus et de données of the RRCancer of the Fonds recherché Québec-santé tumor bank between April 1991 and October 2007. At least 88% of all women with malignant serous, endometrioid or undifferentiated malignant ovarian cancer cases from RRCancer Tumor self reported French Canadian ancestry (unpublished data). All women with serous LMP (Low Malignant Potential) tumors self-reported FC ancestry [30]. None of these subjects were selected for family history of cancer. Histopathology according to criteria established by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), age at diagnosis and personal history of cancer were provided for each case. Written consent to participate was obtained and the study protocols approved by the ethics review boards of the University of Montreal Hospital Center, McGill University Health Centre and Jewish General Hospital.

Table 1.

Families and features of index cases screened for PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] variant

| Syndrome | Number of families1 | Unilateral BC | Bilateral BC | BC and OC | OC | Mean age in years of BC (age range) | Mean age in years of OC (age range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBC |

48

[10] |

45 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

46 (30–65) |

n/a |

| HBOC |

23

[4] |

14 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

44 (25–55) |

51 (31–74) |

| Total | 71 [14] | 59 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 46 (25–65) | 51 (31–74) |

1The numbers in the brackets refer to number of index cases where the complete coding region of PALB2 genes was sequenced. Abbreviations: breast cancer (BC), hereditary breast cancer (HBC) hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC), and ovarian cancer (OC).

Table 2.

Features of ovarian tumors examined for PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] mutation

| Malignancy | Histology type | Number of cases | Prior history of BC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant |

serous |

238 |

10 |

| Malignant |

endometrioid |

49 |

2 |

| Malignant |

mucinous |

24 |

2 |

| Malignant |

clear cell |

31 |

2 |

| Malignant |

undifferentiated |

43 |

1 |

| Low malignant potential |

serous |

56 |

4 |

| Low malignant potential |

endometrioid |

2 |

0 |

| Low malignant potential |

mucinous |

48 |

0 |

| Total | 491 | 21 |

Abbreviation: breast cancer (BC).

PALB2 mutation analysis

Mutation analysis was performed on DNA extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes or from fresh frozen tumor tissue. A sequence analysis of protein coding exons of PALB2 for the index cases of 14 families was performed as described previously [5,10,17] (Table 1). The targeted analysis for PALB2 c.2323C>T (p.Q775X) variant was performed using an allelic specific assay as described [5]. The variant-positive cases were confirmed by DNA sequencing using 3730XL DNA analyzer system platform from Applied Biosystems (Carlbad, CA, USA) at the McGill University and Genome Quebec Innovation Centre (Montreal, PQ, CDN). Sequences were compared with PALB2 NCBI Reference Sequence NM_024675 as described in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). For the Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis, fresh frozen ovarian tumor tissue from the PALB2 p.Q775X mutation-positive case was macrodissected and DNA was extracted from the collected cells using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). The PCR was carried out in a volume of 50 μL, as previously described [5,10]. Sequence data were analyzed using the Lasergene SeqMan Pro sequence analysis software by DNASTAR, Inc. (Madison, WI, USA) and Chromas 2.31 from Technelysium Pty Ltd. (Helensvale, Australia) and compared to the sequences from lymphocyte DNA from PALB2 p.Q775X mutation-positive and mutation-negative cases.

The PALB2 p.Q775X variant is also annotated as p.Q775* according to a recently proposed nomenclature alteration for nonsense changes by the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org). However for historical purposes the p.Q775X designation is maintained in this report.

Results

PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] carriers in breast and/or ovarian cancer families

One PALB2 p.Q775X positive case was identified among the cancer families not previously investigated for PALB2 mutations. The index carrier case was identified among the total of 48 (2.1%) HBC families or 71 (1.4%) HBC and HBOC families that share a phenotype defined by at least three or more confirmed cases of breast and/or ovarian cancer in the same familial branch (Table 1). These families were previously found negative for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations or the most common pathogenic mutations in these genes found in the French Canadian population.

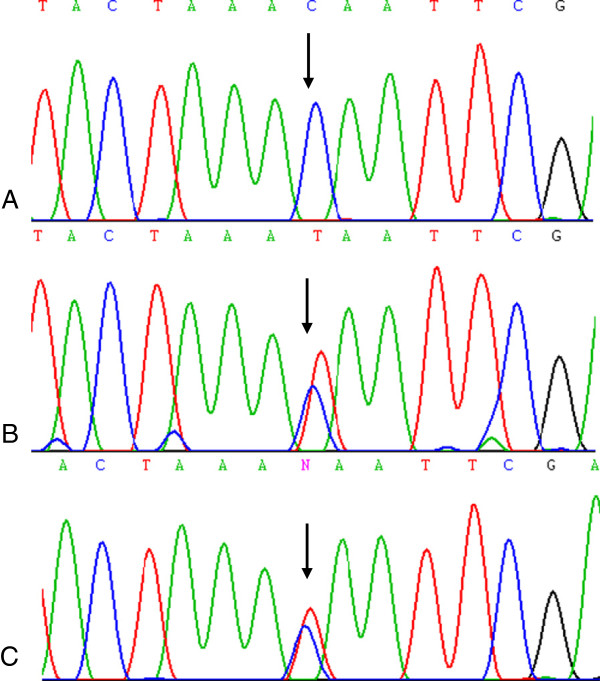

The PALB2 carrier had bilateral invasive ductal carcinomas of the breast at ages 39 and 42 and is part of the breast cancer family F1469 (Figure 1). Although breast cancer was reported in both paternal and maternal branches of her family (Figure 1), only the aunt and cousin from the paternal branch of the family were confirmed to have had breast cancer. Her paternal aunt also had bilateral invasive ductal carcinoma at ages 41 and 42, as well as atypical stomach carcinoma that was identified at age 42 but not further explored due to death soon thereafter. The carrier’s paternal cousin had an invasive breast cancer of mixed ductal and lobular histopathology at 52 and was still living at the time of pedigree analysis. Notable in this pedigree is that lack of ovarian cancer cases typified by BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier families. Her father had esophageal cancer and cancers of other sites reported (some confirmed) for both branches of her family. To our knowledge no other cases are available for genetic testing and thus transmission of the mutation is uncertain in this family. The family structure and associated phenotypes does not appear to overlap previously described PALB2 p.Q775X positive families [5].

Figure 1.

Pedigree of PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] mutation carrier family F1469. An arrow indicates the proband and only known mutation carrier in family F1469. Abbreviations: bilateral breast cancer (Bi Br), cerebral hemorrhage (CH) esophageal cancer (Eso), lung cancer (Lu), melanoma (Mel), stomach cancer (Sto), and uterine cancer (Ut). Age at ascertainment and/or death (d.) are indicated if known along with ages at diagnosis of cancer.

PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] carriers in ovarian cancer cases

One PALB2 p.Q775X positive case was identified among the 491 women with ovarian cancer or low malignant potential tumors. The carrier was diagnosed with a papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma at age 58. The carrier was identified among the 385 (0.3%) invasive ovarian carcinomas of all histopathological subtypes and among 238 (0.4%) invasive serous ovarian carcinomas (Table 2).

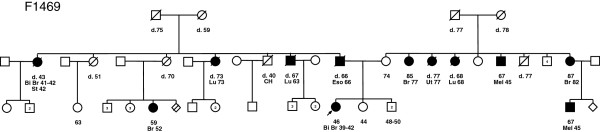

There were 21 cases that also had a prior personal history of breast cancer and the PALB2 p.Q775X carrier was in the group of 10 invasive serous ovarian carcinoma cases with this history (Table 2). The carrier had a breast cancer at age 52 years of undisclosed histological type. Genetic analysis of genomic DNA from ovarian cancer specimens did not indicate LOH of the PALB2 locus (Figure 2) or identify a second mutation in the other coding exons of PALB2.

Figure 2.

Mutation analysis of PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] containing region. DNA sequencing chromatogram showing the region containing the c.2323C sequence of normal reference sample (Panel A) and corresponding interval from lymphocyte DNA of c.2323 T mutation carrier (Panel B) and ovarian cancer specimen DNA from the same patient (Panel C). The arrow indicates the position of the mutation in the sequence chromatogram.

Discussion

Our results are consistent with previously established frequency of PALB2 c.2323C>T [p.Q775X] carriers in breast cancer families of French Canadian descent (Table 3). Initial reports of comprehensive screening of all of the protein encoding exons of PALB2, identified no variants in 38 breast cancer families, where 22 families had a prior probability of greater than 10% of harboring a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation [10]. The same group reported one of 50 (2%) breast cancer families, and two of 356 (0.6%) cases of early age (< 50 years) breast cancer with this mutation [5]. Pedigree analysis of the index PALB2 p.Q775X positive cases from these three families indicated that they are not immediately related to each other and haplotype analysis was consistent with this being a founder mutation [5]. Four PALB2 p.Q775X positive cases were also identified in a subsequent study involving 564 (0.7%) breast cancer cases not selected for family history of cancer, which also showed that 6% of cases harbored common BRCA1, BRCA2 or CHEK2 mutations [29]. This latter study also included the 356 early age breast cancer cases reported in a previous study, and one of these cases was found related to a member of previously reported mutation-positive family (P28031) and two other cases were the same carriers identified in a same previous study (P31030 and P26007) [5] (Table 3). In an independent study involving the investigation of a new BRCA2 variant, c.9004 G>A (E3002K), a family (F1573) harboring both a BRCA2 variant and the PALB2 p.Q775X mutation was reported [22]. However, pedigree inspection revealed that family F1573 was related to one of three PALB2 p.Q775X (P28031) families described in the initial report of this variant in the French Canadian breast cancer families [5]. The family history of PALB2 p.Q775X carrier P36470 also identified in a screen of 564 breast cancer cases not selected for family history [29] appears not to be related to the PALB2 p.Q775X carrier families described based on pedigree inspection, including family F1469 reported in this study. In summary, six PALB2 p.Q775X breast cancer carriers which include five occurring in apparently unrelated cancer families have thus far been identified in screening breast cancer cases or breast cancer families.

Table 3.

Summary of PALB2 c. 2323C>T [p.Q775X] carriers identified in studies of French Canadian cancer families or cases

| p.Q775X positive cases | Features of p.Q775X positive case [Family number] | Number of index cases screened | Context and feature of cases or families tested | BRCA1 and BRCA2 status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

|

22 |

HBC and HBOC families; BRCAPRO scores > 0.10 |

Mutation-negative families |

[10] |

| 0 |

|

16 |

HBC and HBOC families; BRCAPRO scores < 0.10 |

Mutation-negative families |

[10] |

| 1 |

BC 54 [P280311 and (F15732)] |

50 |

BC < 50 years of age, or BC between 50–65 yrs of age with at least one other BC or OC in first or second degree relative |

Mutation-negative families |

[5] (

[22]) |

| 2 |

BC 36 [P260071] BC 49 [P310301] |

3562 |

BC <50 years |

Common French Canadian mutation negative |

[5] |

| 4 |

BC 36 [P260071] BC 46 [P280311] BC 49 [P310301] BC 49 [P36470] |

5642 |

BC <50 years |

Common French Canadian mutation negative |

[29] |

| 0 |

|

99 |

High risk BC families |

Mutation negative |

[31] |

| 0 |

|

21 |

HBC and HBOC families with at least 2 first/second degree relatives with BC |

Mutation negative |

[2] |

| 1 |

BiBC 39–42 [F1469] |

48 |

HBC families (see Table

1) |

Mutation-negative or common French Canadian mutation negative |

This study |

| 0 |

|

23 |

HBOC families (see Table

1) |

Mutation-negative or common French Canadian mutation negative |

This study |

| 1 | BC52;OC58 | 491 | OC (see Table 2) | Not known | This study |

1 Indicates cases identified in the pedigrees identified in independent studies involving 356 BC cases investigated in Foulkes et al. [5] overlap with series of 564 BC cases examined in a subsequent study reported by Ghadirian et al. [29]. 2Pedigrees P28031 and F1573 have related family members and were reported in independent studies [5,22]. Pedigree P28031 had two mutation-positives cancer cases, one as part of HBC family (BC 54) and the other recruited through BC<50 (BC 46) series. Abbreviations: breast cancer (BC), bilateral breast cancer (BiBC) ovarian cancer (OC) hereditary breast cancer (HBC), hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC).

In contrast, no PALB2 variants were reported in two other independent studies involving 99 [31] and 21 [2] independently ascertained breast cancer families of French Canadian descent. Genealogy and genetic studies have reported variability of founder effects in various regions of Quebec [32], suggesting that demography may also be a factor in the paucity of PALB2 p.Q775X carriers in some studies of French Canadian cancer families. The majority of our cases were ascertained in Montreal [20], whereas independent groups have ascertained their families from the Quebec City region [31]. This possibility could also account for the lack of PALB2 p.Q775X carriers found in a screen of 6,440 newborns of French Canadian descent as the majority of these newborns were from the Quebec City region [5].

The young ages of breast cancer diagnoses and number of breast cancer cases per family in PALB2 p.Q775X carrier families suggest that carriers of this mutation are at high risk for breast cancer (Table 3), as has been posited with some PALB2 mutation carrier families [5,10,17]. Our findings here support this notion, as the PALB2 p.Q775X carrier identified had a bilateral case of breast cancer diagnosed before age 45 years and a strong family history of breast cancer (Figure 1).

It is interesting that the PALB2 p.Q775X carrier found among the ovarian cancer cases examined in this study had a prior history of breast cancer (Table 3). Notable is that her personal history of cancer does not match any of the cases that appear in the pedigrees of PALB2 p.Q775X positive French Canadian cancer families described thus far (including the new carrier family identified in this study). The role of PALB2 in ovarian cancer is uncertain, as there have been few documented ovarian carcinoma cases harboring germline mutations in this gene. Two PALB2 mutation carriers were identified in a study of 339 unrelated ovarian cancer cases of Polish descent [3]. The carriers had high grade carcinomas of different histopathological types: serous (case diagnosed at 61 years) and endometrioid (case diagnosed at 54 years) subtypes, where the latter carrier also harbored a BRCA2 mutation [3]. Two (0.6%) PALB2 mutation carriers were reported in a study of 360 ovarian cancer cases that were also screened for BRCA1, BRCA2 and other recently described cancer susceptibility genes [33]. Neither of these two high-grade serous carcinoma PALB2 mutation-carriers (diagnosed at ages 51 and 58) had a personal history of breast cancer, although the ovarian cancer case diagnosed at age 58 years had a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer [33]. A low frequency of PALB2 carriers (0.4%) was also recently reported in an investigation of 253 ovarian cancer cases from the Volga-Ural region of Russia [34], with the only carrier identified in this study having a bilateral (moderate grade) serous ovarian carcinoma at age 46 and a prior history of melanoma. The low frequency of PALB2 mutation carriers identified thus far may argue a minor role for this gene in conferring ovarian cancer risk compared with higher frequency of mutation carriers observed in breast cancer cases and breast cancer families. This is consistent with recent findings estimating that PALB2 heterozygotes were 1.3-fold more likely to have a relative with ovarian cancer in the context of HBOC family history [2].

Our genetic analyses of the carrier ovarian cancer specimen harboring the PALB2 p.Q775X mutation did not exhibit evidence of LOH of the PALB2 locus. This could also be consistent with sufficient contamination of normal stromal DNA such that it would obscure an imbalance of alleles. It has been suggested that PALB2 contributes to carcinogenesis through haploinsufficiency and/or a dominant negative effect given the paucity of LOH observed in the majority of breast cancer cases from PALB2 carriers [3,4,6,10], with the exception of one study where a high frequency of LOH was seen [2]. LOH was observed for both ovarian cancer cases identified in one study [33]. Promoter methylation silencing has also been reported in four of 53 sporadic ovarian cancer cases [35]. The significance of these findings is unknown and warrants further investigation to elucidate the role of PALB2 in both breast and ovarian carcinogenesis.

Conclusion

The PALB2 c.2323C>T [p. Q775X] mutation confers increased risk for breast cancer in the French Canadian population of Quebec. The contribution of PALB2 c.2323C>T [p. Q775X] to the causation of breast cancer in French-Canadians appears to be lesser than that attributable to the most common founder alleles in BRCA1 and BRCA2, but the young age at diagnoses and associated familial history of breast cancer suggest that this variant should be added to the panel of deleterious mutations screened for assessing breast cancer risk in this unique population. Indeed during the preparation of this manuscript another PALB2 carrier harboring the p.Q775X variant was identified in the Hereditary Cancer Clinics affiliated with McGill University Health Centre. The carrier had bilateral breast cancer at ages 34 and 42 years and a strong family history of breast cancer further supporting the notion that PALB2 p.Q775X carriers are at increased risk for breast cancer.

Competing interest

The authors declared that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

MT and PT conceived and oversaw the study and drafted the manuscript, NS and NH performed the molecular analysis. CP, WF, AM and DP recruited cases and provided clinical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Marc Tischkowitz, Email: mdt33@cam.ac.uk.

Nelly Sabbaghian, Email: nelly.sabbaghian@mcgill.ca.

Nancy Hamel, Email: nancy.hamel@mcgill.ca.

Carly Pouchet, Email: cpouchet@jgh.mcgill.ca.

William D Foulkes, Email: william.foulkes@mcgill.ca.

Anne-Marie Mes-Masson, Email: anne-marie.mes-masson@umontreal.ca.

Diane M Provencher, Email: diane.provencher.chum@ssss.gouv.qc.ca.

Patricia N Tonin, Email: patricia.tonin@mcgill.ca.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lise Portelance and Suzanna L. Arcand for technical assistance. We also thank Laura Palma for providing information about a newly identified mutation positive proband. We acknowledge the Banque de tissus et de données of the RRCancer of the Fonds recherche Québec Santé (FRQS) which is affiliated with the Canadian Tumour Repository Network (CRTNet) for providing specimens from cancer families. The Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre and the Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l′Université de Montréal receive support from the FRQS. Marc Tischkowitz a recipient of the FRQS clinician-scientist award. This research was supported in part by a grant from the Cancer Research Society to Patricia N. Tonin, from grants from the Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance, Jewish General Hospital Weekend to End Breast Cancer and the Quebec Ministry of Economic Development to Marc Tischkowitz, and from a grant from the Susan G. Komen for the Cure to William D. Foulkes.

References

- Cao AY, Huang J, Hu Z, Li WF, Ma ZL, Tang LL, Zhang B, Su FX, Zhou J, Di GH. et al. The prevalence of PALB2 germline mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 negative chinese women with early onset breast cancer or affected relatives. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114(3):457–462. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadei S, Norquist BM, Walsh T, Stray S, Mandell JB, Lee MK, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, King MC. Contribution of inherited mutations in the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2 to familial breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(6):2222–2229. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Kluska A, Moes J, Dabrowska M, Nowakowska D, Niwinska A, Derlatka P, Cendrowski K, Kupryjanczyk J. A novel germline PALB2 deletion in polish breast and ovarian cancer patients. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkko H, Xia B, Nikkilä J, Schleutker J, Syrjäkoski K, Mannermaa A, Kallioniemi A, Pylkas K, Karppinen SM, Rapakko K. et al. A recurrent mutation in PALB2 in finnish cancer families. Nature. 2007;446(7133):316–319. doi: 10.1038/nature05609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes WD, Ghadirian P, Akbari MR, Hamel N, Giroux S, Sabbaghian N, Darnel A, Royer R, Poll A, Fafard E. et al. Identification of a novel truncating PALB2 mutation and analysis of its contribution to early-onset breast cancer in french-canadian women. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(6):R83. doi: 10.1186/bcr1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MJ, Fernandez V, Osorio A, Barroso A, Llort G, Lazaro C, Blanco I, Caldes T, de la Hoya M, Ramon YCT. et al. Analysis of FANCB and FANCN/PALB2 fanconi anemia genes in BRCA1/2-negative spanish breast cancer families. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113(3):545–551. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9945-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papi L, Putignano AL, Congregati C, Piaceri I, Zanna I, Sera F, Morrone D, Genuardi M, Palli D. A PALB2 germline mutation associated with hereditary breast cancer in italy. Fam Cancer. 2010;9(2):181–185. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter M, Mew S, van Rensburg EJ. PALB2 Sequence variants in young south african breast cancer patients. Fam Cancer. 2009;8(4):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkowitz M, Xia B. PALB2/FANCN: recombining cancer and fanconi anemia. Cancer Res. 2010;70(19):7353–7359. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkowitz M, Xia B, Sabbaghian N, Reis-Filho JS, Hamel N, Li G, van Beers EH, Li L, Khalil T, Quenneville LA. et al. Analysis of PALB2/FANCN-associated breast cancer families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(16):6788–6793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701724104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia B, Sheng Q, Nakanishi K, Ohashi A, Wu J, Christ N, Liu X, Jasin M, Couch FJ, Livingston DM. Control of BRCA2 cellular and clinical functions by a nuclear partner, PALB2. Mol Cell. 2006;22(6):719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollestelle A, Wasielewski M, Martens JW, Schutte M. Discovering moderate-risk breast cancer susceptibility genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20(3):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman N, Seal S, Thompson D, Kelly P, Renwick A, Elliott A, Reid S, Spanova K, Barfoot R, Chagtai T. et al. PALB2, Which encodes a BRCA2-interacting protein, is a breast cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2007;39(2):165–167. doi: 10.1038/ng1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(20):2143–2153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0802968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Hruban RH, Kamiyama M, Borges M, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Palmisano E, Brune K, Jaffee EM. et al. Exomic sequencing identifies PALB2 as a pancreatic cancer susceptibility gene. Science. 2009;324(5924):217. doi: 10.1126/science.1171202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkowitz MD, Sabbaghian N, Hamel N, Borgida A, Rosner C, Taherian N, Srivastava A, Holter S, Rothenmund H, Ghadirian P. et al. Analysis of the gene coding for the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2 in familial and sporadic pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):1183–1186. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkowitz M, Capanu M, Sabbaghian N, Li L, Liang X, Vallee MP, Tavtigian S, Concannon P, Foulkes WD, Bernstein JL. et al. Rare germline mutations in PALB2 and breast cancer risk: a population-based study. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(4):674–680. doi: 10.1002/humu.22022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge AM, Michaud J, Richter A, Lemyre E, Lambert M, Brais B, Mitchell GA. Population history and its impact on medical genetics in quebec. Clin Genet. 2005;68(4):287–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scriver CR. Human genetics: lessons from quebec populations. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2001;2:69–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonin PN. [The limited spectrum of pathogenic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in the french canadian breast and breast-ovarian cancer families, a founder population of quebec, canada] Bull Cancer. 2006;93(9):841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallone L, Arcand SL, Maugard CM, Nolet S, Gaboury LA, Mes-Masson AM, Ghadirian P, Provencher D, Tonin PN. Comprehensive BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analyses and review of french canadian families with at least three cases of breast cancer. Fam Cancer. 2010;9(4):507–517. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote S, Arcand SL, Royer R, Nolet S, Mes-Masson AM, Ghadirian P, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz M, Narod SA, Provencher D. et al. The BRCA2 c.9004 G>A (E2003K) variant is likely pathogenic and recurs in breast and/or ovarian cancer families of french canadian descent. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):333–340. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oros KK, Ghadirian P, Greenwood CM, Perret C, Shen Z, Paredes Y, Arcand SL, Mes-Masson AM, Narod SA, Foulkes WD. et al. Significant proportion of breast and/or ovarian cancer families of french canadian descent harbor 1 of 5 BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Int J Cancer. 2004;112(3):411–419. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oros KK, Ghadirian P, Maugard CM, Perret C, Paredes Y, Mes-Masson AM, Foulkes WD, Provencher D, Tonin PN. Application of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carrier prediction models in breast and/or ovarian cancer families of french canadian descent. Clin Genet. 2006;70(4):320–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonin PN, Mes-Masson AM, Futreal PA, Morgan K, Mahon M, Foulkes WD, Cole DE, Provencher D, Ghadirian P, Narod SA. Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in french canadian breast and ovarian cancer families. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(5):1341–1351. doi: 10.1086/302099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oros KK, Leblanc G, Arcand SL, Shen Z, Perret C, Mes-Masson AM, Foulkes WD, Ghadirian P, Provencher D, Tonin PN. Haplotype analysis suggest common founders in carriers of the recurrent BRCA2 mutation, 3398delAAAAG, in french canadian hereditary breast and/ovarian cancer families. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning AP, Abelovich D, Ghadirian P, Lambert JA, Frappier D, Provencher D, Robidoux A, Peretz T, Narod SA, Mes-Masson AM. et al. Haplotype analysis of BRCA2 8765delAG mutation carriers in french canadian and yemenite jewish hereditary breast cancer families. Hum Hered. 2001;52(2):116–120. doi: 10.1159/000053364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezina H, Durocher F, Dumont M, Houde L, Szabo C, Tranchant M, Chiquette J, Plante M, Laframboise R, Lepine J. et al. Molecular and genealogical characterization of the R1443X BRCA1 mutation in high-risk french-canadian breast/ovarian cancer families. Hum Genet. 2005;117(2–3):119–132. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadirian P, Robidoux A, Zhang P, Royer R, Akbari M, Zhang S, Fafard E, Costa M, Martin G, Potvin C. et al. The contribution of founder mutations to early-onset breast cancer in french-canadian women. Clin Genet. 2009;76(5):421–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch AH, Arcand SL, Oros KK, Rahimi K, Watters AK, Provencher D, Greenwood CM, Mes-Masson AM, Tonin PN. Chromosome 3 anomalies investigated by genome wide SNP analysis of benign, low malignant potential and low grade ovarian serous tumours. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenard F, Pedneault CS, Ouellette G, Labrie Y, Simard J, Durocher F. Evaluation of the contribution of the three breast cancer susceptibility genes CHEK2, STK11, and PALB2 in non-BRCA1/2 french canadian families with high risk of breast cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14(4):515–526. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon A, Heyer E. Fragmentation of the quebec population genetic pool (canada): evidence from the genetic contribution of founders per region in the 17th and 18th centuries. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;114(1):30–41. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200101)114:1<30::AID-AJPA1003>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, Pennil CC, Nord AS, Thornton AM, Roeb W, Agnew KJ, Stray SM, Wickramanayake A. et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(44):18032–18037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115052108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokofyeva D, Bogdanova N, Bermisheva M, Zinnatullina G, Hillemanns P, Khusnutdinova E, Dork T. Rare occurrence of PALB2 mutations in ovarian cancer patients from the volga-ural region. Clin Genet. 2012;82(1):100–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potapova A, Hoffman AM, Godwin AK, Al-Saleem T, Cairns P. Promoter hypermethylation of the PALB2 susceptibility gene in inherited and sporadic breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(4):998–1002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]