Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has classified prescription drug abuse as an epidemic due to the recent dramatic increase in prescription drug overdose deaths. In addition to an increase in overdose deaths involving opioid analgesics, there has also been an increase in substance abuse treatment admissions and an increase in emergency department (ED) visits for nonmedical use of opioid analgesics [1]. According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network, the estimated number of ED visits for nonmedical use of opioid analgesics more than doubled from 2004 to 2008 (from 144,600 to 305,900 visits) [2]. Although quantifying the amount of opioids prescribed from an ED in comparison to other specialties has been a challenge, data from the 2003–2004 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey suggest that the ED accounts for 39 % of opioid administration or medical record prescription mentions compared with 30.5 % for primary care offices [3]; however, this source does not likely account for the small total amount prescribed from the ED. Analyses of the Vector One National database suggest that ED physicians are among the top five outpatient specialties prescribing opioids to patients 39 years old and younger along with primary care physicians, dentists, and pediatricians [4]. Among individuals who abused prescription opioids upon entering methadone treatment, 13 % reported obtaining their opioids from EDs; [5] Washington State Department of Health (WSDOH) had been concerned regarding data suggesting higher rates of drug overdose deaths and a higher percentage of nonmedical use of prescription pain medication in Washington State compared to the rest of the nation [6]. In 2010, opioid analgesic prescribing per capita in Washington State was significantly higher than the national average—ranking ninth in the nation. In addition, Washington State ranked 14th in the nation in drug overdose deaths in 2008 [1].

Addressing Prescription Opioids in the ED

Due to concerns regarding the high prescribing and death rates, staff at WSDOH started an interagency workgroup in 2008. The interagency workgroup included members from various state government departments, emergency physicians, pain physicians, addiction physicians, and other partners (see Table 1). The purpose of the group was to coordinate prevention activities, to create a forum for continuing communication, and to develop short-term actionable strategies.

Table 1.

Members of the Washington State Department of Health interagency workgroup

| Board of Pharmacy | Medical boards and commissions with prescriptive authority |

| Emergency department physicians | Office of the Attorney General |

| Health plans | State government |

| Law enforcement | University of Washington |

| Local public health jurisdictions | Washington Poison Control Center |

| Medicaid | Workers compensation |

| Mental health | Pain and addiction physicians |

Concern about patients frequenting the ED to obtain prescription opioids led the ED physicians on the interagency workgroup to create a prevention action “to identify and promote possible methods to reduce emergency department visits for chronic pain and requests for opioid medication refill.” There were several reasons to focus on EDs for prevention of prescription drug abuse: (1) ED providers prescribed a substantial amount of prescription opioids; (2) At the time, several guidelines existed for chronic non-cancer opioid prescribing [7–9], but guidelines for acute prescribing were more limited and did not address chronic non-cancer opioid prescribing in the ED or include clinical advice about suggested dosing; (3) Data from Washington State Department of Social and Health Services showed Washington State Medicaid clients who frequently visited EDs received more opioid prescriptions and had high rates of alcohol or drug disorders and other mental illness (Data from 2002 showed a linear relationship between ED visits and opioid prescriptions. A Medicaid client with one ED visit received three opioid analgesic prescriptions on average from all healthcare settings for that year, and a Medicaid client with 31 or more ED visits received 42 opioid analgesic prescriptions on average) [10]; (4) A few Washington State EDs had implemented programs to help manage the care of frequent ED visitors and were experiencing good results (An important part of these programs was to share individualized ED patient care plans among EDs. However, a statewide mechanism to share patient ED visit data did not exist); (5) There was concern about the cost of unnecessary ED visits; (6) There was confusion about whether the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act required treatment of pain with specific medication (there was similar concern regarding Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requirements for treating and documenting pain); (7) It was recognized that interactions with patients suspected of doctor shopping were a great source of frustration and stress for ED providers.

The ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup

To begin working on the ED-specific, short-term prevention action, a subgroup of the interagency workgroup, the ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup, was formed in April 2009 and chaired by an ED physician (corresponding author). Initially, the group included four ED physicians and several state agency staff. Physician members of the ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup were emergency physicians and not chronic pain or primary care physicians. The group met via monthly conference calls. The members encouraged the expansion of membership among other ED providers and the subgroup grew to over 50 participants, including providers from neighboring states. The two main goals of this workgroup were to (1) draft prescribing guidelines and (2) encourage the use of an Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) for data sharing.

Draft guidelines began with four recommendations, which expanded over time. One of the initial recommendations was to encourage the use of EDIE to share ED patient visit history data and individualized ED patient care plans among hospitals. Part of this objective was to reduce diversion, yet it was also essential to preserve the primary role of the ED provider to treat patients with emergent medical conditions.

EDIE is a proprietary internet-based software application operated by Collective Medical Technologies. EDIE collects ED patient registration data from participating facilities, aggregates the data, and then proactively alerts ED care providers when high utilization and special needs patients present to the ED before patients are seen by the providers. EDIE sends alerts by fax, text, voice, or email depending on hospital preference and does not require providers to access data on a web interface. Once notified, care providers can use EDIE to review ED visit information from other participating facilities and to access individualized ED patient care plans to better address the patient's medical issues.

The EDIE provides the ED provider data different from that available through a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). The PDMP provides a history of controlled substance prescriptions filled. [Washington State's PDMP data did not become accessible to providers until January 2012.] The data obtained by the ED provider from the PDMP can be missing controlled substance prescriptions from the previous 7 days because Washington pharmacies are only required to upload data every 7 days. This allows a patient to present to multiple EDs to obtain opioid prescriptions and then fill them for 7 days before the pattern of multiple opioid prescriptions would be available from the PDMP. The EDIE can alert the ED provider of all the ED visits from EDIE participating hospitals including the most recent. This allows the ED provider to be alerted by EDIE, usually by fax immediately after the patient registers in the ED, if the patient has a pattern if multiple ED visits. The fax sent to the ED provider by the EDIE can include a listing of recent ED visits including the location, date, and diagnosis of each ED visit along with an ED care plan for the patient and a listing of medical providers and facilities that Washington Medicaid has restricted the patient to obtaining care from under the Patient Review and Coordination Program (PRC). The information regarding ED visits that EDIE provides can include ED visits where the patient was unsuccessful in obtaining prescription opioids. By contrast, the data from the PDMP contain only successfully filled prescriptions. The EDIE system provides a proactive surveillance system to alert the ED provider of patients who may be making frequent ED visits to obtain prescription opioids. This system could curtail ED drug-seeking behavior when these patients realize their drug-seeking efforts will not be successful. The system also provides opportunities for ED providers to address patient’s need for addiction treatment. The EDIE system can confirm if a fax alerting the provider was received by the ED but cannot verify the provider reviewed the information. Work to integrate the information included in the EDIE fax into ED information systems so it is part of the ED provider's workflow needs to be done by most Washington hospitals.

EDIE was first implemented at Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center & Children's Hospital in Spokane, WA in 2008 to manage patients in an ED care coordination program, Consistent Care. This program coordinated the care of frequent ED visitors by creating individualized ED patient care plans and sharing the care plans on a regional hospital information system within Eastern Washington Hospitals. ED patient care plans were created by an ED case manager who contacted each patient and their primary care provider and when needed presented the case to a multidisciplinary committee for review.

Before the ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup, EDIE had only been used in one hospital to manage the ED care coordination of frequent ED users. Convincing other hospitals of its importance was a challenge. The second hospital to implement EDIE, Evergreen Hospital in Kirkland, WA, was motivated by a very low introductory monthly fee and the benefits of identifying frequent ED users within their own facility. The third hospital to implement EDIE, Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, WA, shared ED patients with Evergreen Hospital due to its proximity and wanted take advantage of the inexpensive information-sharing capabilities of EDIE to identify frequent ED users. Subsequently, a large hospital system, Franciscan Health Care, saw the potential for sharing ED information and implemented EDIE at five of its hospitals, thus creating the critical mass for the EDIE network to expand to other EDs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Expansion history of EDIE adoption by Washington State hospitals

| Year | No. of hospitals |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 1 |

| 2010 | 3 |

| 2011 | 16 |

| 2012 | 84 expected by October 2012 |

There are a total of 87 hospitals with an ED in Washington State. Seventy-five percent of hospitals were required to adopt EDIE by June 15, 2012

By April 2010, the group had draft recommendations. To determine whether there was majority approval on the recommendations, an anonymous web-based survey was conducted where 52 workgroup members who resided in Washington were emailed an invitation to complete the survey. The survey listed each of the recommendations and asked the respondents if they agreed or had specific comments. The response rate for the survey was 67 %. Support for each of the individual recommendations ranged from 69 to 97 %. The guideline with 69 % approval was “for acute exacerbations of chronic pain, dispense sufficient pills to last until the patient's primary opioid prescriber's office opens.” Based on survey comments, those in disagreement with this guideline were concerned more about the maximum number of days a prescription should contain and not disagreement about the guideline itself. The survey results were not published and subsequent changes to the guidelines by the Washington chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians (WA-ACEP) were not approved by the ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup. The final Washington Emergency Department Opioid Prescribing Guidelines are listed in Table 3 and the full version is available at http://washingtonacep.org/painmedication.htm.

Table 3.

Washington ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines (abbreviated)

| Washington ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines |

|---|

| 1. One medical provider should provide all opioids to treat a patient's chronic pain |

| 2. The administration of intravenous and intramuscular opioids in the ED for the relief of acute exacerbations of chronic pain is discouraged |

| 3. Emergency medical providers should not provide replacement prescriptions for controlled substances that were lost, destroyed, or stolen |

| 4. Emergency medical providers should not provide replacement doses of methadone for patients in a methadone treatment program |

| 5. Long-acting or controlled-release opioids (such as OxyContin®, fentanyl patches, and methadone) should not be prescribed from the ED |

| 6. EDs are encouraged to share the ED visit history of patients with other emergency physicians who are treating the patient using an Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) system |

| 7. Physicians should send patient pain agreements to local EDs and work to include a plan for pain treatment in the ED |

| 8. Prescriptions for controlled substances from the ED should state that the patient is required to provide a government-issued picture identification (ID) to the pharmacy filling the prescription |

| 9. EDs are encouraged to photograph patients who present for pain-related complaints without a government-issued photo ID |

| 10. EDs should coordinate the care of patients who frequently visit the ED using an ED care coordination program |

| 11. EDs should maintain a list of clinics that provide primary care for patients of all payer types |

| 12. EDs should perform screening, brief interventions, and treatment referrals for patients with suspected prescription opioid abuse problems |

| 13. The administration of Demerol® (meperidine) in the ED is discouraged |

| 14. For exacerbations of chronic pain, the emergency medical provider should contact the patient's primary opioid prescriber or pharmacy. The emergency medical provider should only prescribe enough pills to last until the office of the patient's primary opioid prescriber opens |

| 15. Prescriptions for opioid pain medication from the ED for acute injuries, such as fractured bones, in most cases should not exceed 30 pills |

| 16. ED patients should be screened for substance abuse prior to prescribing opioid medication for acute pain |

| 17. The emergency physician is required by law to evaluate an ED patient who reports pain. The law allows the emergency physician to use their clinical judgment when treating pain and does not require the use of opioids |

While the guidelines were under development, they were implemented in a derivative form at EDs in the Swedish Hospital system in Seattle. The preexisting Swedish policy on ED opioid prescribing, developed in 2005, had many similarities to the developing guidelines but was felt to be ineffective. The ED Medical Director at Swedish Medical Center Cherry Hill, Russell Carlisle, MD, advocated a new program, “The Oxy-Free ED: rational prescribing of controlled substances in the ED.” The Oxy-Free program contained each of the draft guidelines with the addition that schedule II opioid prescriptions were only to be used in exceptional circumstances. The Oxy-Free program was implemented as a transparent policy that was posted in the ED waiting room and distributed upfront to all potentially affected patients early in the ED visit.

The Oxy-Free program was approved after it was presented first to the Cherry Hill ED physicians group then hospital administration and medical leadership including the Medical Executive Committee. The Oxy-Free program was then presented to and approved by the other EDs in the Swedish system (now four hospital EDs and three free standing EDs). The policy was later also adopted by several competing hospitals nearby and hospitals in other states, gaining a degree of national recognition because of an interview on EM: RAP in March 2011 [11]. To garner support for the Oxy-Free policy both initially within Swedish and then at other hospitals, data were presented to hospital leaders about the increasing problem of prescription drug addiction, overdose deaths, recent media reports about teen overdose deaths, reports from the literature questioning the effectiveness of opioid analgesics for chronic pain, and the CDC's recommendations to healthcare providers about opioid prescribing. The Oxy-Free program served as a pilot implementation for the WA-ACEP guidelines. The program had widespread acceptance by ED physicians and nurses with a perceived marked reduction in conflict and stress. This was attributed to a resetting of the patient's expectations early in the ED visit and a perception by the patient that the opioid prescription process was less arbitrary and discriminatory.

Sponsorship for ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines

Once the workgroup reached consensus, a sponsor was needed for the guidelines. It was determined that a government agency such as the Washington Department of Health should not be sponsoring a guideline which provided prescribing recommendations. WA-ACEP was chosen because it was the leading organization in Washington State representing ED providers. A request was submitted to the 20-member WA-ACEP board to consider sponsoring the guidelines. Two WA-ACEP board members were also members of the ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup. It was not felt that these two ED physicians could have a conflict of interest due to their involvement with developing the guidelines but viewed as part of the collaboration by WA-ACEP in the development of the guidelines. The initial response from the board was mixed, and the primary reasons for limited interest included: (1) EDs were not contributing to the problem and therefore guidelines are not necessary; (2) Emergency physicians were experts in treating acute pain and did not need new guidelines; and (3) Pain is the fifth vital sign and ED providers are required to manage pain or risk lack of accreditation by the Joint Commission. There was also concern that patient satisfaction in the EDs would be diminished, which in turn would adversely impact accreditation and other performance measures.

The ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup was able to address all of the concerns regarding guidelines 2, 3, 9, 14, and 17 listed in Table 3 that the WA-ACEP board raised. The WA-ACEP board agreed to sponsor the guidelines which did not imply that ED providers cannot treat pain. The WA-ACEP board also requested patient educational materials accompany the guidelines as an important way in which to inform patients about the guidelines in simple language. The approved guidelines were presented to all ED directors at the 2010 WA-ACEP Leadership Summit. There was unanimous support for guidelines to address prescription drug abuse, but not all of the guidelines. [Note: Concerns included specific details such as taking photos of individuals without ID and having primary care providers submit pain contracts. All guidelines were approved despite concerns.] After WA-ACEP agreed to be the primary sponsor of the guidelines, endorsement was sought and obtained from the state medical and hospital associations and state emergency nurses association.

Patient Education Material Development

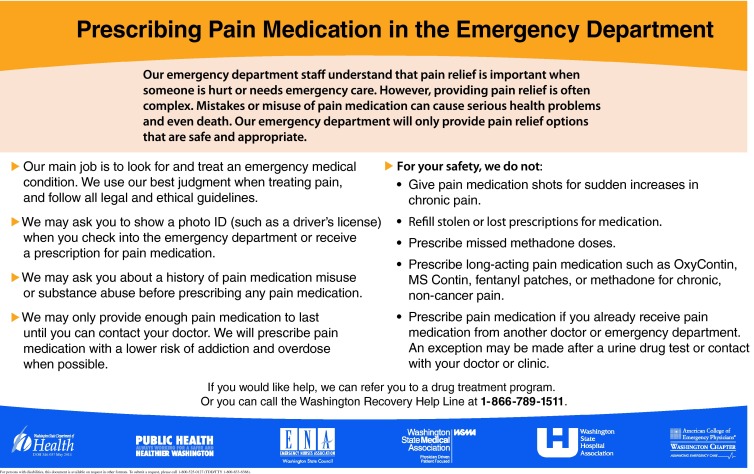

The patient education materials were developed by the subgroup and staff in the Health Promotion Practice and Policy Section (HPPPS) at WSDOH and funded by a grant from the CDC to the WSDOH Injury and Violence Prevention Program. Based on the research literature and ED observations, it was determined that posters in the ED waiting room were the most appropriate educational method. Staff in HPPPS audience tested the posters with ED patient populations using intercept interviews asking about message clarity, content comprehension, tone, graphic appeal, and dissemination method to develop the final poster. The posters were translated into Spanish and Russian and were posted on the WSDOH website at http://here.doh.wa.gov/materials/prescribing-pain-medication for downloading along with a patient education brochure created in 2012 at http://here.doh.wa.gov/materials/pain-medication-guidelines/33_EDopiodHO_E12L.pdf.

Guideline and Poster Dissemination

The guidelines were disseminated in June 2011 by WA-ACEP through their listserv and posted on their website [12]. A large poster (20 × 30 in.) for every ED waiting room and smaller posters (17 × 11 in.) for every examination room were mailed by WSDOH in July 2011 (See Fig. 1 for example of a poster). Mailings included an attached letter of explanation signed by representatives from WA-ACEP, WSDOH, the hospital, and medical associations and a copy of the guidelines. Printing and mailing the posters were funded using approximately US$3,500 from the aforementioned CDC grant to WSDOH.

Fig. 1.

Example of ED patient education poster

Feedback, Questions, and Barriers

Thus far, feedback received for the guidelines and patient education materials has been overwhelmingly positive. A survey of mostly medical directors at the 2011 WA-ACEP leadership conference (1 year after the guidelines were approved) produced 34 responses from 65 attendees. All respondents reported being familiar with the guidelines and 85 % had read them in detail. Over 90 % reported that their EDs had adopted either all of the guidelines (60 %) or almost all of the guidelines (30 %). A quote from an ED director in southwestern Washington provides an illustrative example, “The RNs are heartily on board as are the MDs. We can now point to statewide guidelines, supported by a number of organizations that justify our clinical decisions. It's no longer personal.”

There were several questions from EDs after dissemination. Most frequently included the following: “Are EDs required to implement these guidelines?” Our response: “No. These are guidelines and not policies, so therefore are not required.” “How do we find out more information about EDIE?” Our response was to provide contact information for the vendor providing this service.

Three main barriers were encountered during this process. The first was concern about potentially lower patient satisfaction survey scores. It is our impression that patient education materials appeared to have reduced this concern to some degree by changing patient expectations. Anecdotally, several of the Swedish EDs that implemented the Oxy-Free program had a brief and small increase in complaints but did not see a long-term increase in complaints and experienced an improvement in patient satisfaction scores. That being said, patient satisfaction remains a significant barrier for ED providers to limit ED opioid prescribing. ED providers remain concerned that limiting opioids from the ED will negatively impact patient satisfaction scores. New methods to account for these patients in satisfaction surveys need to be developed and may be addressed in the next version of the guidelines. A request has been made to the ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup by an ED physician to create a guideline that addresses patients who complain to hospital administration about an ED provider who denied the patient's request for controlled substances. These patients may be motivated to be less than truthful when making complaints regarding their care in order to discipline doctors who follow the guidelines. The workgroup will consider recommending independent corroboration of the physician's behavior in such circumstances. The second barrier was the unanticipated difficulty in mailing posters to every ED in the state. In some cases, the posters were sent three different times to the same ED before receipt. In hindsight, email notification prior to the mailing may have been helpful. The third barrier was cultural resistance to sharing patient data among hospitals; this made the adoption of EDIE more difficult. As more hospitals participate in EDIE, this resistance has been reduced. It was particularly helpful to have an ED physician “champion” in a hospital who had access to and had credibility at the highest levels of hospital administration. It was also important to emphasize to the hospital administration the importance of data sharing to improve patient's safety, as well as the potential hospital savings from reductions in unreimbursed and under-reimbursed healthcare from ED visits made by high utilizers.

Prescription Opioids and Heroin

The abuse of prescription opioids by patients who then transition to abusing heroin is concerning and not well studied. There is evidence from Seattle that 39 % of heroin users presenting to needle exchange reported they were “hooked” on prescription opioids before using heroin [13]. There is little published information about why this transition occurs. We speculate that the higher street price of prescription opioids compared with heroin is the main driver combined with the recent reformulation of OxyContin to a less easily abused form. It is possible that increased difficulty with obtaining prescription opioids both illicitly and through doctor shopping has fueled the transition to heroin. While efforts to reduce inappropriate opioid prescribing such as the WA-ACEP ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines contribute to reducing the supply of illicitly traded prescription opioids, the principle intent is to prevent patients from becoming addicted to prescription opioids and obtain treatment for those who are addicted.

Medicaid Requires EDs to Adopt Guidelines

In parallel to the efforts of the ED Opioid Abuse Workgroup, Washington State Medicaid became increasingly concerned about rising costs related to inappropriate ED visits, particularly frequent visits by enrollees frequently visiting EDs for pain-related complaints. In response, Medicaid officials established a policy wherein any medically unnecessary emergency room visit would not be reimbursed as of April 2012. Members from the Washington State Hospital Association, the Washington State Medical Association, and WA-ACEP appealed to the legislature, resulting in the enactment of a budget proviso enabling hospitals an opportunity to avoid this no-payment policy by adopting seven “best practices” to reduce unnecessary ED visits. The legislation required 75 % of hospitals to start implementing the best practices by June 15, 2012. The seven best practices include (1) patient education about appropriate use of EDs, (2) exchange of patient information between EDs, (3) implementation of the WA-ACEP ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines, (4) identification of Medicaid clients who are frequent ED users and clients enrolled in the Medicaid lock-in program, the patient review and coordination program (PRC), and education of these clients on proper ED utilization during their ED presentation, (5) creation of an individualized ED care plan for PRC clients, (6) enrollment of 90 % of ED providers with the PDMP, and (7) regular review of utilization reports provided by the Medicaid program. During an 8-week implementation, the Washington State Hospital and Medical Associations and the WA-ACEP worked together to provide hospitals with the information and tools to accomplish this goal.

As a result, all of the hospitals in Washington State have attested to the implementation of these seven best practices. It is anticipated that all but three hospitals in Washington State will be sharing ED visit information and ED patient care plans using EDIE by October 2012. Evaluations are underway to assess the effectiveness of the policy change.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Bureau of Justice Affairs (PI: Roll, J., Co-Is: Howell, D., Neven, D.). The authors would also like to acknowledge the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for a grant (U17CE0248110) supporting the work of the WA ED Opioid Workgroup.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs—United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(23):705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raofi S, Schappert SM. Medication therapy in ambulatory medical care: United States, 2003–04. Vital Health Stat. 2006;13(163):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1299–1301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenblum A, Parrino M, Schnoll SH, Fong C, Maxwell C, Cleland CM, Magura S, Haddox JD. Prescription opioid abuse among enrollees into methadone maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids among medicaid enrollees—Washington, 2004–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(42):1171–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Utah Department of Health. 2008. Utah clinical guidelines on prescribing opioids. http://health.utah.gov/prescription/pdf/Utah_guidelines_pdfs.pdf. Accessed 23 Jul 2012

- 8.American Pain Society, American Academy of Pain. 2009–2010. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. http://www.painmed.org/files/opioid-treatment-guidelines-chronic-noncancer-pain.pdf. Accessed 23 Jul 2012

- 9.Federation of State Medical Boards of the UNited States, Inc. 2004. Model policy for the use of controlled substances for the treatment of pain. 2004 http://www.fsmb.org/pdf/2004_grpol_Controlled_Substances.pdf. Accessed 23 Jul 2012

- 10.Mancuso D et al. (2004) Frequent emergency room visits signal substance abuse and mental illness. DSHS Research and Data Analysis Division, http://www.dshs.wa.gov/pdf/ms/rda/research/11/119-31.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2012

- 11.Rob Orman M, Russell Carlisle, MD Dave Craig, MD, The “Oxy Free” ED. EM:RAP. 2011. https://www.emrap.org/episode/2011/march/theoxyfreeed?emrap=ibjbcslii Accessed 31 Aug 2012

- 12.Washington Chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians, The Washington ED Opioid Prescribing Guidelines. 2011. http://washingtonacep.org/Postings/edopioidabuseguidelinesfinal.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2012

- 13.Peavy KM, et al. “Hooked on” prescription-type opiates prior to using heroin: results from a survey of syringe exchange clients. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2012;44(3):259–265. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2012.704591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]