Abstract

Prescription opioid analgesic misuse and addiction are a significant public health concern in the USA. Through their concurrent roles as prescribers and public health stewards, medical toxicologists (MTs) have a unique perspective on this issue. They represent a physician group with a particular interest in prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) because of their subspecialty knowledge of the negative consequences of opioid overprescribing in terms of misuse, diversion, addiction, and overdose death. This study surveyed a national sample of MTs about their opioid prescribing patterns and their knowledge and use of PDMPs. A link to a Web-based survey was disseminated by email to the physician membership of the American College of Medical Toxicology. The survey assessed the circumstances and details of the respondents prescribing practices for opioids and their knowledge and use of PDMPs. This included focused questions regarding their perceived limitation of their current PDMP. Responses were received from 205/445 surveys (46 %), representing responses from 35 states. The majority (78 %) of MTs responding to the survey reported that they primarily practice emergency medicine. Although awareness of PDMPs, in general, was high, approximately 25 % reported no knowledge of or did not have access to their state’s PDMP. Barriers to use included time and complexity required to access relevant information. MTs prescribe opioids primarily to patients in the Emergency Department (ED) for acute pain or acute exacerbations of chronic pain. MTs are generally aware of PDMPs, although many were unaware of or not using their state-based PDMPs when prescribing opioids in clinical practice.

Keywords: Prescription drug monitoring programs, Opioid misuse, Safe opioid prescribing, Opioid diversion

Introduction

Opioid analgesics are commonly used in the management of acute pain and rescue treatment for acute exacerbations of chronic pain. Increasingly, opioid prescribing is challenged by concerns over the rising prevalence of opioid abuse and diversion [1]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that Emergency Department (ED) visits for nonmedical use of opioid analgesics increased 111 % from 2004 to 2008 [2]. Nonmedical use was defined as use of a prescription pain reliever without a prescription belonging to the patient or use for the experience or feeling the drug induces. Legitimate sales of prescription opioids increased fourfold between 1999 and 2010 [3] and use of prescription opioids per person increased 402 % from 1997 to 2007 [4]. This rise in opioid prescribing has been accompanied by a parallel increase in opioid addiction, diversion of these drugs for recreational or nonmedical use, and fatal overdose [2, 3]. National data show that, by 2009, drug-induced death, the majority of which were due to opioid analgesics, had become the number one cause of injury death in the USA, exceeding the number of deaths from motor vehicle crashes [3].

Many solutions to curb this epidemic including those based in educational, regulatory, and enforcement models have been proposed [5]. In particular, it is increasingly suggested that state-based prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), which exist in 44/50 states, can contribute to safer opioid prescribing, detect and limit nonmedical opioid use, and thereby reduce opioid poisoning and deaths [6]. A PDMP is a state-maintained database that collects patient-, prescriber-, and pharmacy-level prescription information regarding controlled medications and typically allows access to prescribers to evaluate a patient’s medication history. Although currently inadequately funded, of variable functionality, and inconsistently used, PDMPs represent a potentially beneficial but underutilized resource to help control the misuse of prescription opioids.

Medical toxicologists (MTs) are frequently involved in the care of opioid-poisoned patients through their roles in poison centers as well as inpatient and outpatient medical toxicology consultation services. In addition, the majority of MTs maintain active patient care responsibilities, primarily in EDs, and prescribe opioids for pain in these clinical settings. Emergency physicians are among the top five opioid prescribers in patients under the age of 40 years [7].

Within this varied experience, we sought to characterize MT physician’s perspectives toward opioid prescribing and their knowledge and use of PDMPs. In addition, we also surveyed MTs about their use of and perceived limitations of their state’s PDMP. Ideally, this information could be used to guide future development and expansion of new and existing PDMPs. We hypothesized that MTs would demonstrate conservative opioid prescribing practices and high awareness of PDMPs.

Methods

A survey of MTs was designed by the authors and piloted through colleagues with iterative adjustment. The anonymous survey was formatted using an online survey tool (www.surveymonkey.com). A link to the survey was distributed using an electronic mailing list to the membership of the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) following approval of the ACMT Research Committee (see Appendix for survey). At the time of this survey members of ACMT were all physicians either board certified in medical toxicology or currently in a fellowship training program, although the primary training and current practice of members vary. The survey contained an Internet-based consent script, where the signature is replaced with the affirmative decision to continue the survey in lieu of written informed consent. All recipients had the option of not participating in the study with no repercussions to their ACMT membership. There were no exclusion criteria. Approximately 90 % of all board-certified MTs in the USA are members of ACMT. The study was approved by the IRB of the University of Pennsylvania.

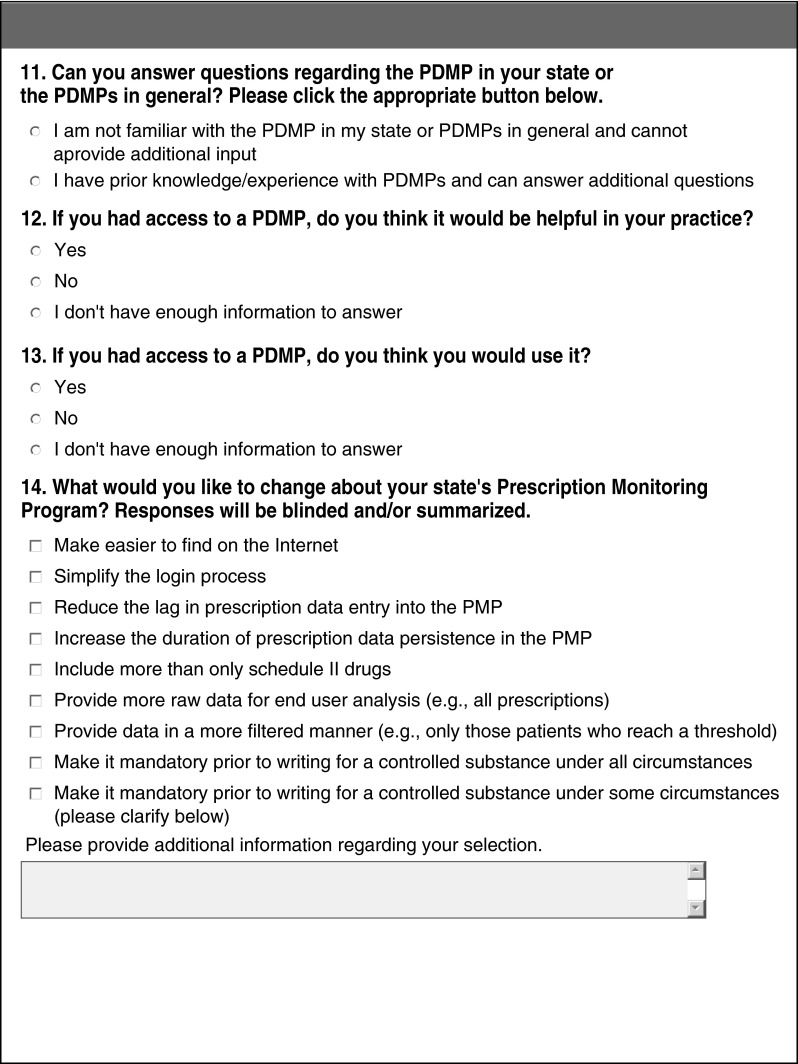

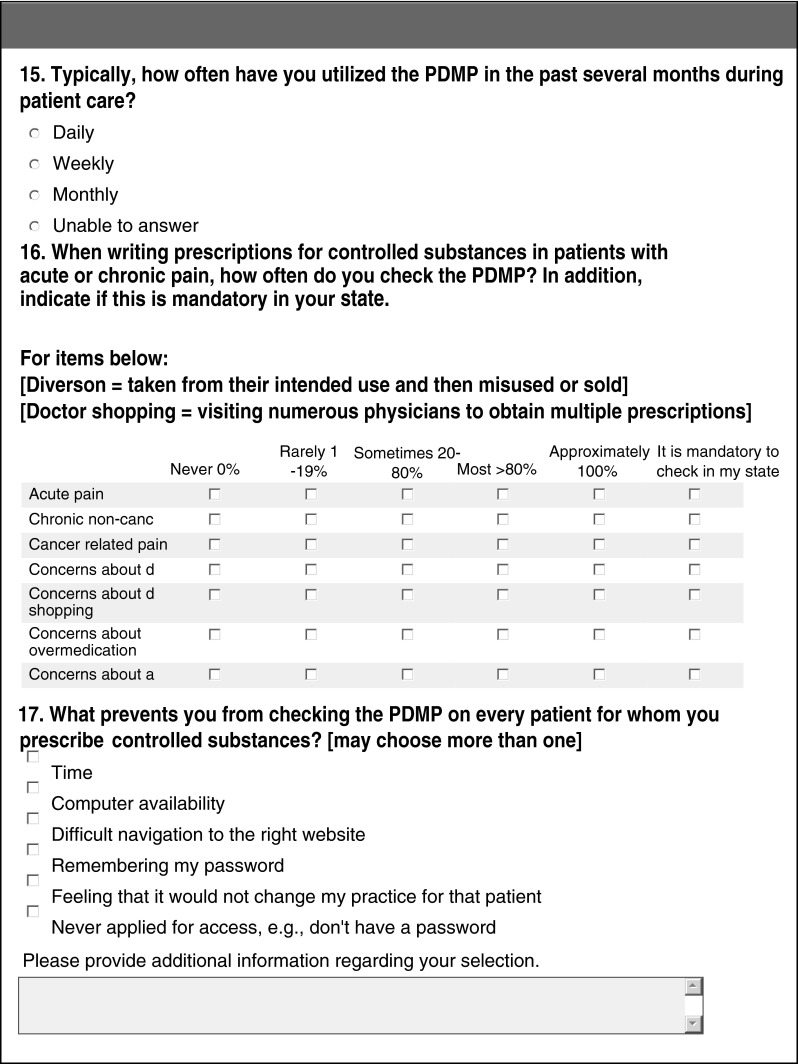

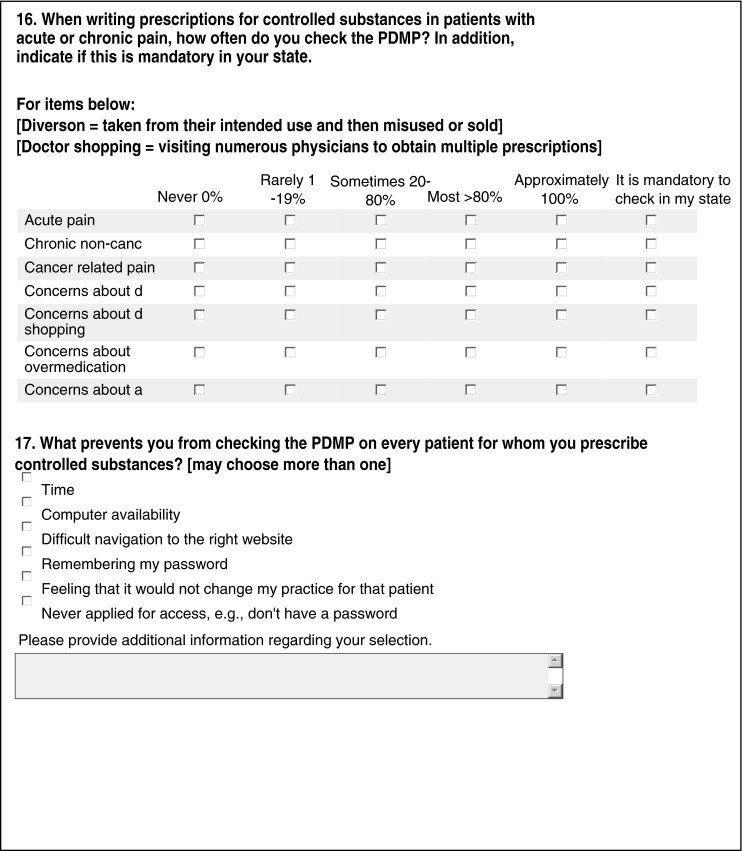

The survey assessed the respondents’ frequency and patterns of opioid prescribing and their understanding and use of their state’s PDMP. The respondents were provided discrete answer options appropriate for the question along with a free text box. Examples of the questions and answer options are provided in Table 1 and Appendix. Several of the survey items allowed respondents to select more than one option so that the cumulative response may be greater than 100 %. Responses to most nondemographic questions did not require a response to progress. Additionally the use of branching logic, in which different responses direct the respondent to different subsequent questions, reduced the response rate for some questions.

Table 1.

Responses to selected items on the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) online survey regarding opioid prescribing patterns

| Do you prescribe long-acting or extended release opioids (e.g., transdermal fentanyl, oral methadone, oxycodone sustained release)? (175 respondents) | |

| Yes, based on my clinical judgment | 8.0 % |

| Yes, but only for verified refills (e.g., computer verification, appropriately timed empty container) | 12.0 % |

| Yes, but if new prescription only in consultation with a patient's primary care or pain management provider | 6.3 % |

| Yes, to treat severe pain more continuously | 0.6 % |

| No | 73.1 % |

| Under what circumstances would you support the requirement for mandatory review of a PDMP prior to writing a controlled substance prescription? (95 respondents; may answer more than once) | |

| Prescriptions for more than 3 days of medication | 12.6 % |

| Prescriptions for more than 5 days of medication | 24.2 % |

| Prescribing of a schedule II medication | 27.4 % |

| Prescribing to any patient unknown to the prescriber | 23.2 % |

| Prescribing to patients screening positive for risk factors for misuse | 54.7 % |

| Under no circumstances should it ever be mandatory | 34.7 % |

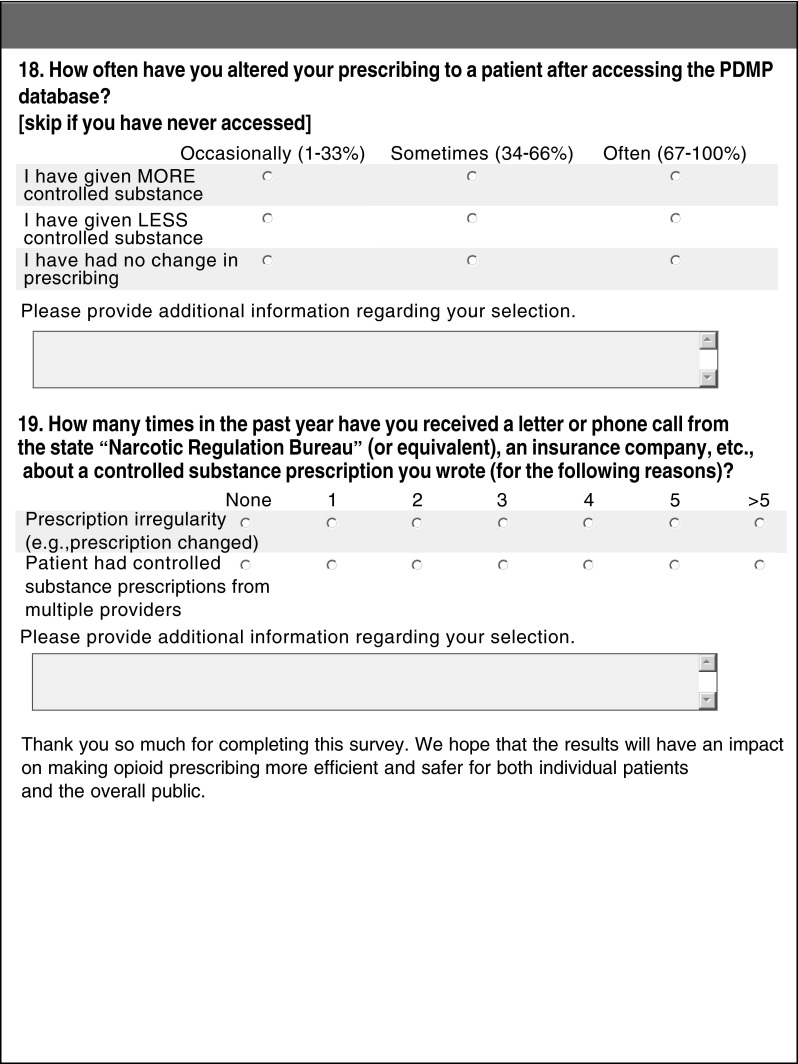

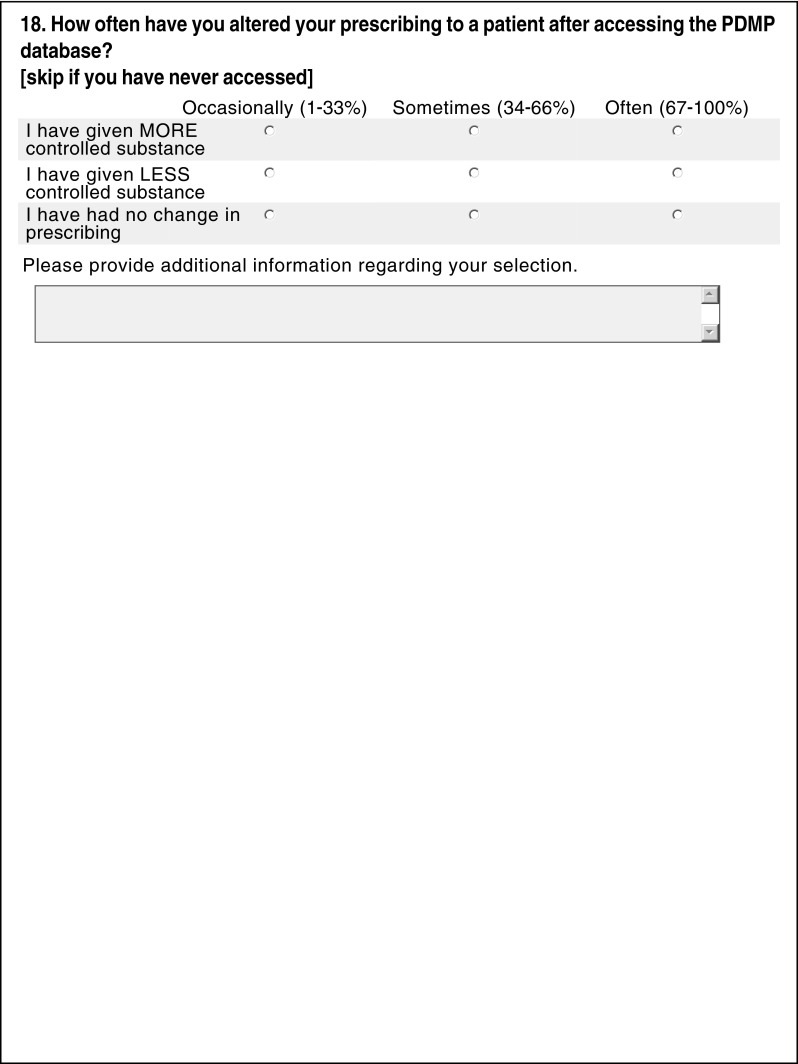

| How often have you altered your prescribing to a patient after accessing the PDMP database? (90 respondents) | |

| Given more of a controlled substance | 68 % |

| Given less of a controlled substance | 87 % |

| Occasionally changed practice (1–33 % of time accessed) | 81 % |

| Often changed practice (67–100 %) | 20 % |

The survey was initially emailed in November 2011 with a reminder at 3 and 6 weeks after the initial survey was sent. The anonymous online survey was utilized for 2 months to collect responses.

Analysis Plan

Results were collated and reported in aggregated form to determine overall provider attitudes toward opioid prescribing and PDMP use. Aggregation of results assured that the data would remain anonymous. All analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft Office Excel 2003). Descriptive statistics were used.

Results

Surveys were sent to 445 members and were completed by 205 respondents for an overall response rate of 46 %. Due to the design of the study, the response rate to each question does not equal the total number of respondents. Surveys were obtained from respondents in 34 states and the District of Columbia and represented the spectrum of physician practice experience from 3 to 46 (mean 16.8) years of patient care including training.

Demographics and Physician Practice

Most of the respondents (78 %; 138/173) practice emergency medicine for a significant portion of their clinical responsibilities. Some physicians also practice in toxicology outpatient settings and on toxicology inpatient services. Almost three fourths (73.5 %; 128/174) of the respondents report substantial clinical responsibilities, caring for more than 30 patients weekly. Of those who practice in emergency medicine primarily, 66 % work in academic EDs and 31 % work in community ED settings. Respondents also report working in poison centers (31 %; 54/173) and toxicology clinical consulting services (55 %; 95/173).

Opioid Prescribing

The majority of respondents who prescribe opioids (80.4 %; 139/173) do so primarily in their clinical practice of emergency medicine. When prescribing opioids, most respondents prescribed short courses of opioids for less than 7 days whether treating acute (85.6 %) or chronic (61 %) pain. Some physicians reported writing prescription of longer duration when treating patients with cancer pain [1–7 days (49.1 % of respondents), 8–14 days (28 %), 15–30 days (7 %), and >30 days (6 %)]. The majority (73 %; 128/175) do not prescribe long-acting or extended release opioid formulation, although 12 % have done so when the indication was verifiable (Table 1).

PDMP Knowledge and Use

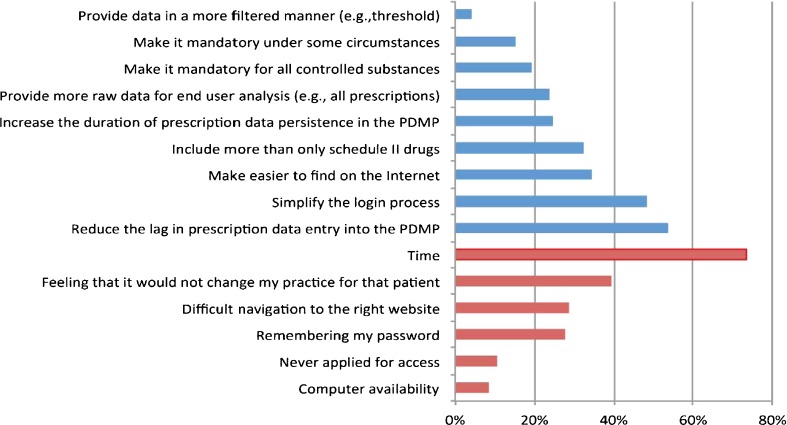

Although only 27.3 % (47/172) of survey respondents reported in-depth knowledge about PDMPs, the vast majority (87.2 %; 150/172) had at least some knowledge. However, more than a quarter did not access their state’s PDMP because they were either not knowledgeable about the availability of a PDMP in their state (13.5 %; 23/170) or not registered for use of their state’s PDMP access (12.4 %; 21/170). Approximately half (50.6 %) of all respondents have used their state’s PDMP, with 30 % of those accessing it daily, 47 % weekly, and 23 % monthly. The reasons for not using it “whenever they prescribe opioids” are shown in Fig. 1. Respondent’s responses to the practical changes they would make in their state’s PDMP are also shown in this figure.

Fig. 1.

Responses to the following survey items. A What prevents you from checking the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) on every patient for whom you prescribe controlled substances? (red). B What would you like to change about your state’sPDMP? (blue). [See Table 2 for selected additional responses in free text fields.] (Color figure online)

Additional details of the responses are provided in Table 1.

Discussion

This survey confirms that knowledge of the existence and utilization of PDMPs varies among MTs, most of whom practice emergency medicine. In a small survey of physicians from five specialties at one academic medical center in Ohio, a state with a well-developed PDMP, over 84 % were aware of the existence of their monitoring program [11]. However, less than 60 % of those who were aware of their PDMPs had ever used it. This is similar to the findings in our study that 87 % of MTs were aware of PDMPs, but about half had actually accessed one.

We surveyed a national group with varied access to a spectrum of state PDMPs; however, it was difficult to classify physician’s responses based on the functionality of their state’s PDMP. Despite this drawback, several potentially modifiable barriers to use were frequently identified (Fig. 1). Overall, “time” was the most often cited limitation preventing their use, but password requirements and applying for access were also identified as important barriers. Most respondents recommended simplifying the complexity of locating and accessing the PDMP database. This parallels the concerns that respondents are identified as hurdles to routine use of the database, which were primarily related to time. Although some of these obstacles require significant infrastructural support and funding, such as computer availability, other require more moderate efforts such as creating a more user-friendly URL or user-modifiable passwords. Additional comments can be found in Table 2 (and in Appendix).

Table 2.

Selected responses to items noted in the figure

| What prevents you from checking the PDMP on every patient for whom you prescribe controlled substances? |

| Long lag between submitting a request and a response |

| Patient has an objective source of pain |

| False names or other identifying information limit utility |

| What would you like to change about your state’s prescription drug monitoring program? |

| Cross state lines |

| National not state-based |

| Simplify the application process |

Additional responses may be found in Appendix

More than half identified the need to improve the delay to prescription data availability in the PDMP. Oklahoma recently incorporated a system that integrates pharmacy scanning of prescriptions in real time, keeping the database virtually current at all times. The estimated cost of that software implementation was $21,000 [12]. E-prescribing may similarly allow for direct population of the PDMP by both the prescriber and the dispenser.

An additional barrier identified to routine use of the PDMP is the perception by the prescriber that it would not change their prescribing practice. This reflects the concerns expressed over the time lag to data entry into the PDMP. Other comments suggested that some patients, even those known to be aberrant opioid users, may not be “monitored” with the system due to multiple aliases. Although only 20 % of our respondents indicated that the PDMP frequently altered their prescribing, the majority suggested that it did so at least occasionally. When the amount of opioid analgesic prescribed was changed, it was done so nearly equally in both directions.

This study had several limitations. Although we had data from 205 respondents, the overall response rate was only 46 %. This may be expected given the varied nature of the practices of ACMT members (e.g., inactive clinicians, international members). Whether those who responded are distinct from those who failed to respond is not readily known due to the anonymous nature of the survey. The majority of MTs who responded to this survey primarily practiced emergency medicine and prescribed opioids in that capacity and primarily for short-term pain relief. We did not have a control group of nontoxicologist emergency physicians as this study was designed to provide an overview of the practices of MTs. Additionally, we were not able to verify that each participant who reported that they used their state’s PDMP practiced in a state with an available program. However, at the time of this survey, PDMPs were available in 44/50 states.

Medical toxicology is a discipline that incorporates the diagnosis and management of patients exposed to or adversely affected by a medication or drug of abuse. The majority of board-certified MTs are initially trained in emergency medicine, although a substantial minority have backgrounds in pediatrics, occupational medicine, or internal medicine. In addition to providing direct care to exposed patients, many MTs are involved with the public health consequences of exposures through work at poison control centers or in public health education.

The properly designed and implemented PDMP has several benefits including the potential to identify patients with potentially high-risk or aberrant behavior for further scrutiny or early addiction interventions. Furthermore, providing assurance to prescribers that the risk of nonmedical use is minimized allows increased opportunity for more judicious opioid prescribing to benefit patients. In addition, a PDMP could have significant public health impact through a reduction in opioid diversion, misuse, addiction, and overdose.

Although many states have “operational” PDMPs, their functional attributes vary widely and their impact on both public health and individual patients remains unclear. An ED study of PDMP use demonstrated that a PDMP can have a significant effect on an individual’s prescribing practice [8]; the clinical outcome of this change was not evaluated. One outcome study found that states with PDMPs did not demonstrate lower prescription opioid mortality or opioid consumption rates than those without [9], although a different study identified a slower rate of rise of opioid exposure calls to the poison center in the former group [10]. However, all these studies are limited by confounding (e.g., states more likely to have a PDMP may have higher abuse rates), and more importantly, these studies combined results from various state PDMPs despite the heterogeneous designs of the programs. Additionally, since PDMP programs have undergone substantial revision in recent years, including transformation into Internet-based platforms, these analyses may be based on historical data that is no longer current.

Conclusions

MTs are generally aware of the presence of PDMPs, although they may not be utilizing their respective programs. Several limitations of existing PDMPs were identified by the respondents to the survey. The largest impediment is the time needed to access the PDMP. The belief that the data will not be sufficiently current to impact prescribing was also common. These findings should be considered as PDMPs are redesigned and enhanced.

Appendix

Contributor Information

Jeanmarie Perrone, Phone: +1-215-6623665, Email: jeanmari@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Francis J. DeRoos, Email: Francis.DeRoos@uphs.upenn.edu

Lewis S. Nelson, Email: Lnelsonmd@gmail.com

References

- 1.Paulozzi LJ, Baldwin G, Franklin G, et al. CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses—a U.S. epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(1):10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs—United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulozzi LJ, Jones CM, Mack KA, Rudd RA. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manchikanti L, Fellow B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Phys. 2010;13:401–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of National Drug control policy (2011) Epidemic: Responding to America’s prescription drug abuse crisis. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/rx_abuse_plan.pdf. Accessed 14 May 2012

- 6.Gugelmann HM, Perrone J. Can prescription drug monitoring programs help limit opioid abuse? JAMA. 2011;306(20):2258–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1299–1301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baehren DF, Marco CA, Droz DE, Sinha S, Callan EM, Akpunonu P. A statewide prescription monitoring program affects emergency department prescribing behaviors. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Desai HA. Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose. Pain Med. 2011;12(5):747–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reifler LM, Droz D, Bailey JE, Schnoll SH, Fant R, Dart RC, Bucher Bartelson B. Do prescription monitoring programs impact state trends in opioid abuse/misuse? Pain Med. 2012;13(3):434–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman L, Williams KS, Coates J, Knox M. Awareness and utilization of a prescription monitoring program among physicians. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25(4):313–317. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2011.606292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Alliance Monitor. http://www.pmpalliance.org/content/pmp-coe-notes-field-oklahoma%E2%80%99s-real-time-reporting. Accessed 14 May 2012