Abstract

Branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) rarely cause neovascular glaucoma (NVG). A 58-year-old woman with hypertension and type 2 diabetic mellitus complained of progressive visual loss in her right eye for the previous 3 months. At initial examination, visual acuity was 20 / 63 in the right eye. Angle neovascularization was observed and the intraocular pressure (IOP) was 30 mmHg in her right eye. Fundus examination and fluorescein angiography showed BRAO combined with BRVO. We immediately injected intravitreal and intracameral bevacizumab in her right eye. The next day, we performed scatter photocoagulation in the nonperfusion area. One month later, visual acuity was 20 / 20 in her right eye and the IOP was 17 mmHg with one topical antiglaucoma agent. The neovascularization had regressed completely. We report a case of unilateral NVG which was caused by BRAO with concomitant BRVO and advise close ophthalmic examination of the iris and angle in BRVO with BRAO.

Keywords: Branch retinal artery occlusion, Branch retinal vein occlusion, Neovascular glaucoma, Neovascularization, Retinal ischemia

Neovascular glaucoma (NVG) is difficult to manage and often results in severe visual loss [1]. Early diagnosis followed by immediate management is the key to a better visual outcome. For early diagnosis, it is essential to maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with predisposing diseases. Diabetic retinopathy, ischemic central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) and ocular ischemic syndrome are by far the most common causes of NVG [1,2]. Both branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) may rarely cause NVG, but the incidence is very low as the risk of NVG is proportionate to the extent of retinal ischemia.

In this report, we describe an unusual case of NVG which stemmed from the combination of rare causes: BRAO and BRVO. To the best of our knowledge, NVG associated with BRVO combined with BRAO is rarely reported.

Case Report

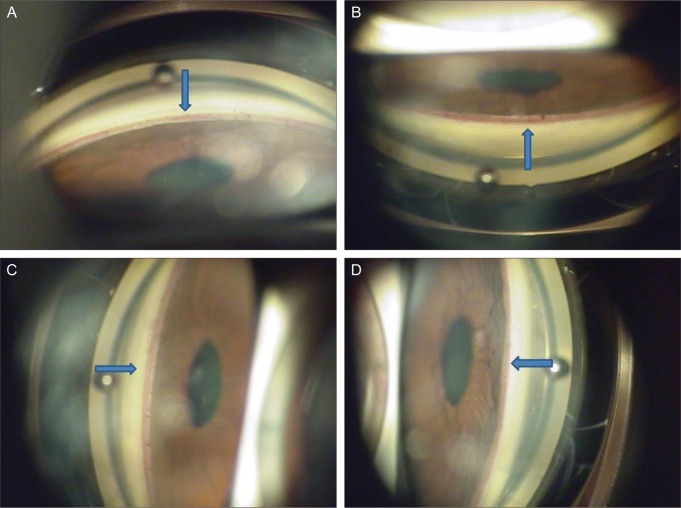

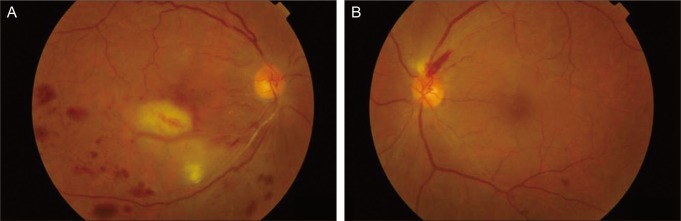

A 58-year-old Korean woman was referred for progressive blurred vision in her right eye for the previous 3 months. She was admitted for acute left cerebellar and right basal ganglia infarction 1 week prior and received acetylsalicylic acid therapy (100 mg once a day) in the neurology department. She had a 20-year history of hypertension and a 2-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, but was not currently taking any medication. On initial ophthalmic examination, visual acuity was 20 / 63 in the right eye and 20 / 20 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure (IOP) of the right eye was 30 mmHg and 10mmHg in the left eye. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the right eye showed iris neovascularization (NVI) and gonioscopy revealed 360 degrees of angle neovascularization (NVA) (Fig. 1). The anterior segment of her left eye was normal but fundus examination revealed a single peripapillary flame hemorrhage temporally and narrowing of the arterial vessels. Funduscopic examination of her right eye showed scattered retinal hemorrhage along the inferotemporal vein and ischemic edema in the inferior parafoveal area which was supplied by the small branches of the inferior retinal artery with atheroma (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Gonioscopic examination at initial examination showed 360 degree angle neovascularization (NVA) of the right eye. Arrows indicate NVA. (A) The gonioscopy revealed inferior NVA. (B) The gonioscopy revealed superior NVA. (C) The gonioscopy revealed nasal NVA. (D) The gonioscopy revealed temporal NVA.

Fig. 2.

(A) In right eye, fundus examination showed scat tered retinal hemorrhage along the inferotemporal vein and ischemic edema in the inferior parafoveal area which was supplied by the small branches of the inferior retinal artery with atheroma at initial examination. (B) In left eye, fundus examination revealed a single peripapillary flame hemor rhage temporally and narrowing of the arterial vessels at initial examination.

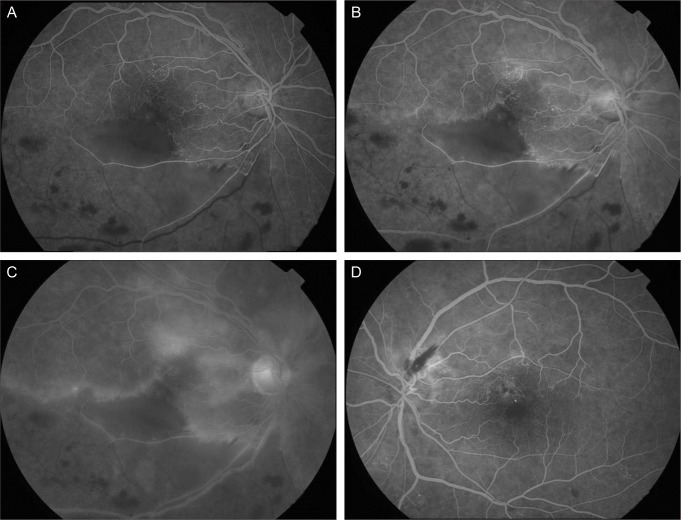

Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye showed significant delayed filling of the branches of the inferior retinal artery in the ischemic area. The foveal avascular zone was widened and the superior border was irregular with moderate leakage of dye from the arterioles. A wide area of capillary nonperfusion in the distribution of the inferotemporal vein was also noticed, but choroidal perfusion was normal in the right eye. In her left eye, arteriolar tortuosity and moderate leakage was found near the flame hemorrhage (Fig. 3). FA was consistent with BRAO combined with BRVO in her right eye and the impending state in her left eye.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescein angiography (FA) at initial visit. (A) In right eye, FA of the right eye showed significant delayed filling of the branches of the inferior retinal artery in the ischemic area (30 seconds). (B) The foveal avascular zone was widened and the superior border was irregular with moderate leakage of dye from the arterioles (70 seconds). (C) A wide area of capillary nonperfusion in the distribution of the inferotemporal vein was also noticed, but choroidal perfu sion was normal in the right eye (10 minutes). (D) In left eye, arteriolar tortuosity and moderate leakage was found near the flame hemorrhage (70 seconds).

Carotid Doppler sonography and echocardiogram showed no evidence of systemic conditions associated with multiple emboli and thrombosis. Her laboratory data including lipid profile, blood coagulation test, and serum homocystein were normal except for blood glucose.

We immediately injected intravitreal and intracameral bevacizumab (0.4 mg/0.05 mL) in her right eye. The next day, we performed scatter photocoagulation in the nonperfusion area. One week after the injection, the NVI and NVA had regressed, and the IOP was 12 mmHg with topical antiglaucoma medication (dorzolamide/timolol fixed combination). One month later, visual acuity returned to 20 / 20 in her right eye and the IOP was 17 mmHg with topical antiglaucoma medication (dorzolamide/timolol fixed combination).

Discussion

NVI and the subsequent development of NVG are serious complications seen in patients with ischemic retinal disorders such as diabetic retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion and central retinal artery occlusion [2,3].

Hayreh et al. [4] have attributed NVI and NVG associated with CRAO to underlying atherosclerotic carotid artery disease and also reported that not one of the 44 eyes in their study with BRAO showed NVI or NVG. In the study by Hayreh et al. [4] on ocular neovascularization associated with retinal vein occlusion, none of the 264 eyes with BRVO developed NVG. The studies have indicated that it usually requires at least half or more of the retina to have ischemic involvement to provide an adequate neovascular stimulus [4,5]. Thus, there is little risk of NVG following BRVO or BRAO.

In our case, two rare causes of NVG (BRVO and BRAO) simultaneously developed to cause NVG. We assumed that the angiogenic factors produced by the different lesions interacted synergistically and reached a level sufficient for angiogenic stimuli to develop NVG. In addition to this, an unrevealed underlying disease might have enhanced the angiogenic stimuli. De Salvo et al. [6] reported that when retinal artery and vein occlusion occurred in the same eye, a systemic disorder should be suspected. In our patient, FA revealed multiple arteriolar obstructions in both eyes, which suggest that the embolic and thrombotic event could be systemic or disseminated emboli. Recent multiple brain infarctions could be more evidence of systemic embolism, even though we could not find an underlying disorder.

As observed in our case, ophthalmologists should be aware that NVI and NVG may occur as possible complications of BRAO combined with BRVO, and patients should be followed up carefully with repeated slit-lamp examinations and undilated gonioscopy.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Hayreh SS. Neovascular glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26:470–485. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shazly TA, Latina MA. Neovascular glaucoma: etiology, diagnosis and prognosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2009;24:113–121. doi: 10.1080/08820530902800801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sivak-Callcott JA, O'Day DM, Gass JD, Tsai JC. Evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of neovascular glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1767–1776. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayreh SS, Rojas P, Podhajsky P, et al. Ocular neovascularization with retinal vascular occlusion-III. Incidence of ocular neovascularization with retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:488–506. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky P. Ocular neovascularization with retinal vascular occlusion. II. Occurrence in central and branch retinal artery occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:1585–1596. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040563002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Salvo G, Li Calzi C, Anastasi M, Lodato G. Branch retinal vein occlusion followed by central retinal artery occlusion in Churg-Strauss syndrome: unusual ocular manifestations in allergic granulomatous angiitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:314–317. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]