Abstract

Objective

Meningiomas represent 18-20% of all intracranial tumors and have a 20-50% 10-year recurrence rate, despite aggressive surgery and irradiation. Hydroxyurea, an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, is known to inhibit meningioma cells by induction of apoptosis. We report the long-term follow-up result of hydroxyurea therapy in the patients with recurrent meningiomas.

Methods

Thirteen patients with recurrent WHO grade I or II meningioma were treated with hydroxyurea (1000 mg/m2/day orally divided twice per day) from June 1998 to February 2012. Nine female and 4 male, ranging in age from 32 to 83 years (median age 61.7 years), were included. Follow-up assessment included physical examination, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Standard neuro-oncological response criteria (Macdonald criteria) were used to evaluate the follow-up MRI scans. The treatment was continued until there was objective disease progression or onset of unmanageable toxicity.

Results

Ten of the 13 patients (76.9%) showed stable disease after treatment, with time to progression ranging from 8 to 128 months (median 72.4 months; 6 patients still accruing time). However, there was no complete response or partial response in any patients. Three patients had progressive disease after 88, 89, 36 months, respectively. There was no severe (Grade III-IV) blood systemic disorders and no episodes of non-hematological side effects.

Conclusion

This study showed that hydroxyurea is a modestly active agent against recurrent meningiomas and can induce long-term stabilization of disease in some patients. We think that hydroxyurea treatment is well tolerated and convenient, and could be considered as an alternative treatment option in patients with recurrent meningiomas prior to reoperation or radiotherapy.

Keywords: Meningioma, Chemotherapy, Hydroxyurea, Recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial meningiomas are extra-axial tumors that constitute approximately 20% of all intracranial neoplasms, with an incidence of 2-7 per 100000 in women and 1-5 per 100000 in men16,30). Surgical treatment is the primary therapy, but the recurrence rate even in totally resected benign tumors (Simpson Grades 1-3) is approximately 10 to 20% after 5 years, 20 to 30% after 10 years, and approximately 50% after 20 years of follow-up review1,34). Treatment options at recurrence of incomplete resection include : further surgery, conventional external beam irradiation, stereotactic radiosurgery and systemic therapies9,21). Hydroxyurea is an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase and interferes with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis in the S-phase. Schrell et al.32) were the first to describe the use of hydroxyurea in patients with inoperable meningiomas, in a small pilot study reported in 1997. Four patients were enrolled in their study, each with a tumor that had grown into or originated from the cavernous sinus. This study showed surprising results : tumor shrinkage in three patients and stabilization in the four33). Therefore, we began to use hydroxyurea for recurrent meningioma. In our preliminary report of 4 meningioma patients treated with hydroxyurea, the drug was modestly active against meningioma and well tolerated, with stabilized disease seen in all patients15). We report here our experience with hydroxyurea therapy in a more expanded cohort of patients with recurrent meningiomas who were followed up for an extended period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 331 meningioma patients were treated surgically between January 1988 and February 2012 in our department. Thirteen patients with recurrent meningioma were treated with hydroxyurea from June 1998 to February 2012. Criteria for initiating hydroxyurea therapy included the following : 1) histologically confirmed diagnosis of meningioma; 2) neuroimaging evidence of recurrence; 3) Karnofsky Performance Status rating of 60 or higher; 4) life expectancy longer than 3 months; 5) recurrent tumors in locations associated with higher risk for re-resection or patient do not want surgery. Thirteen patients, ranging in age from 32 to 83 years (mean 62.7 years), were enrolled into the study (Table 1). Nine patients were female and four were male. Eight of 13 patients with WHO grade I meningioma and five patients with WHO grade II had recurrent meningioma. Two patients had undergone some form of irradiation prior to chemotherapy. The laboratory parameters necessary to begin treatment were as follows : WBC greater than 3000/uL, platelet count greater than 100000/uL, bilirubin less than 2 mg%, and creatinine less than 2 mg%. Each patient was started on a daily oral dose of hydroxyurea (1000 mg/m2/day) at the start of therapy. Treatment with hydroxyurea was repeated every 28 days. Blood work was evaluated every 4 weeks and at clinical follow-up visits (including a complete physical and neurological examination), which were scheduled every 4 weeks. Treatment-related toxicity and complications were graded using the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.0. Tumor assessment was performed by serial magnetic resonance imaging at 3 months, 6 months and yearly, using standard neuro-oncological response criteria defined as : complete response (CR), complete resolution of the enhancing tumor volume, and an improved or normal neurological examination without steroid medication; partial response (PR), greater than 50% reduction of the enhancing tumor volume and a stable or improved neurological examination on stable or decreased doses of steroid; stable disease (SD), less than 50% reduction or 25% growth of enhancing tumor volume without a significant change in the neurological examination on stable or decreasing doses of steroids; and progressive disease, greater than a 25% increase of the enhancing tumor volume. Hydroxyurea was discontinued in the patient if the disease showed signs of progression, unacceptable toxicity developed.

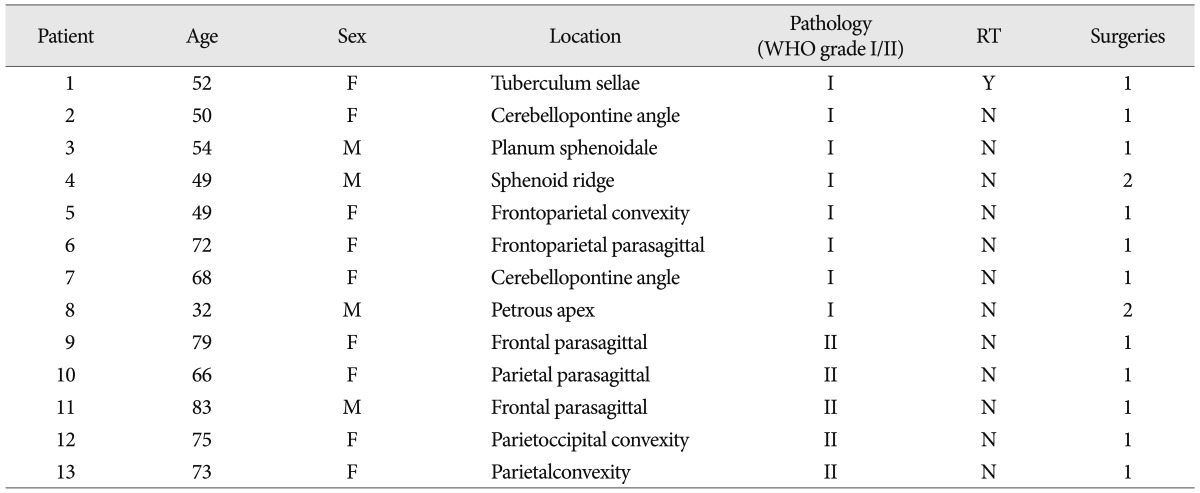

Table 1.

Demographic data of meningioma patient cohort receiving hydroxyurea chemotherapy

RT : radiation therapy, F : female, M : male, Surgeries : numbers of surgery

RESULTS

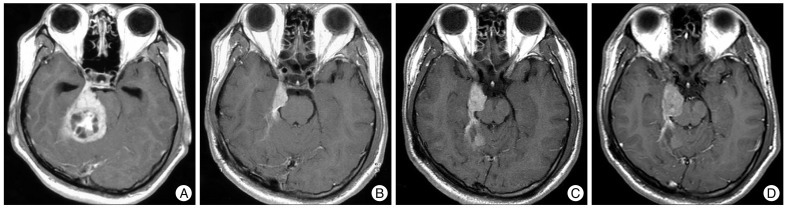

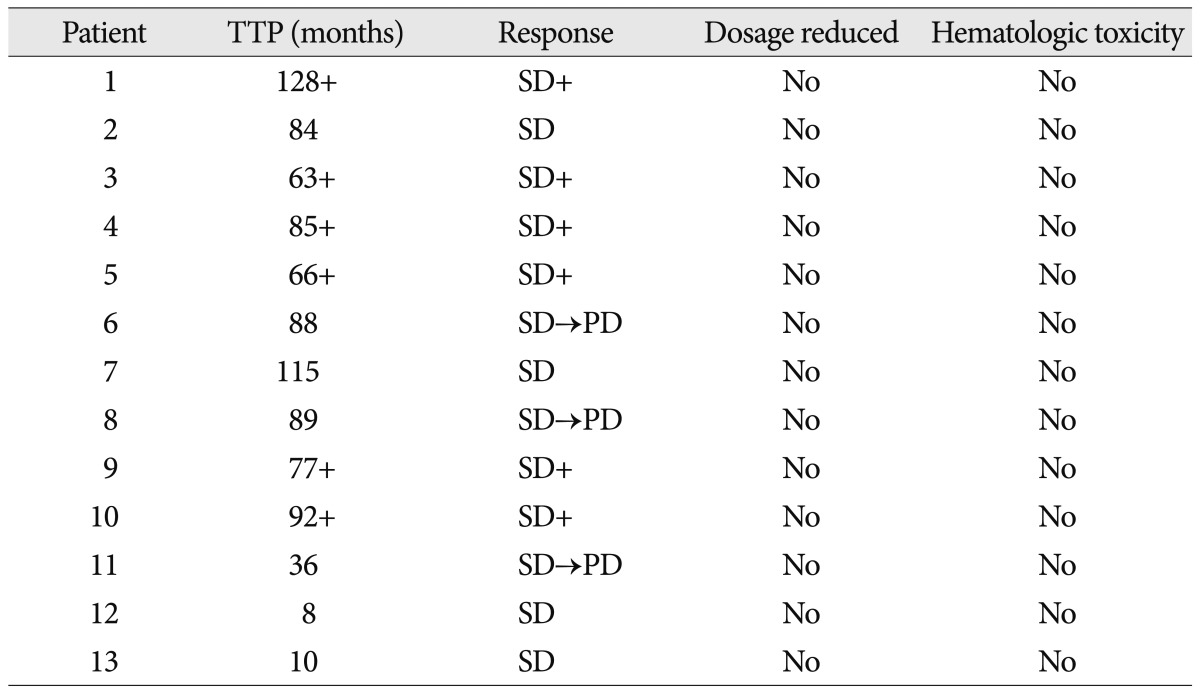

Patient's responses to hydroxyurea chemotherapy are listed in Table 2. All 13 patients were evaluable for radiographic responses, treatment-related toxicity and complications. The mean follow-up periods were 77.1 months, with a range of 19-128 months. The median time to progression (TTP) was 77 months (range 8-128), with 6 patients still receiving treatment and accruing time at the time of the reporting of this study. The median TTP of grade I group was 90 months, and grade II group was 45 months. Ten of 13 patients (76.9%) had SD with TTP of ranging of 8 to 128 months; there was no CR or PR. A patient with a petrous apex meningioma had recurrence 42 months after the surgery. We started this patient on a daily oral dosage of hydroxyurea (1000 mg/m2/day). The patient's tumor has not progressed for 89 months (Fig. 1). Three patients developed progressive disease. These three patients had SD that lasted 88, 89, and 36 months, respectively, before tumor progression. Hydroxyurea was well tolerated; toxicity was retrospectively recorded for all patients by type and grade using the CTCAE version 4.0. The most common toxicity was hematological, with reduction in white blood cell. There was no severe (Grade III-IV) blood systemic disorders; two patients with leukopenia were taken off drug therapy for a few days and the patients recovered. No severe toxicity was noted and no patients required dose reduction. And, there were no episodes of non-hematological side effects.

Table 2.

Response and toxicity date of meningioma patient cohort receiving hydroxyurea chemotherapy

TTP : time to tumor progression, SD : stable disease, PD : progressive disease, + : following up at present

Fig. 1.

Axial T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) images of patient 8 in Table 1, 2. A : Preoperative MR image demonstrating an enhancing mass lesion at the petrous apex with brainstem compression. B : Postoperative MR image demonstrating a remained mass lesion at petrous apex. C : MR image at 42 months after the operation demonstrating increased the mass. Hydroxyurea was started. After then, the tumor had been a stable disease. D : MR image at 89 months after initiation of hydroxyurea treatment demonstrating more increase the tumor and midbrain was compressed by tumor mass.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of recurrent meningiomas

25 to 50% of all surgically treated meningiomas are incompletely resected or will recur because of their intracranial location1,34). The likelihood of premature death in patients with WHO grade I and II tumors who undergo subtotal tumor removal is 4.2 times higher than in those who undergo total removal13). Recurrent meningiomas are managed by re-resection when clinically indicated and surgically accessible, otherwise radiotherapy is most often employed6). Retrospective analyses suggested that postoperative radiation therapy for residual lesions of meningioma might prevent or delay tumor progression and improve disease-free survival, but the efficacy of radiation for recurrent tumors remains controversial7). Forbes and Goldberg8) reported a 4-year relapse-free survival rate of 67% after radiation therapy for recurrent meningiomas. This study shows a 4-year relapse-free survival rate of 75% in twelve patients who were treated with only hydroxyurea therapy for recurrent meningiomas. To obtain higher local control rates, higher doses of radiation would be necessary using more sophisticated techniques28). Compared to conventionally fractionated radiation, radiosurgery clearly has short term advantages, such as reduced length of hospital stay, reduced patient costs and early return to pretreatment functional status29). Nevertheless, studies with longer follow-up periods and a larger number of patients are required to be able to sufficiently assess the long term outcome of radiosurgery11). The role of systemic treatment for recurrent meningioma remains contentious31). A number of agents have been examined including tamoxifen, mifespristone, interferons and systemic chemotherapy3,12,14). In general, these agents have been associated with low response rates and modest toxicity. The 2011 Central Nervous System National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines suggest these possible treatments (hydroxyurea, alpha-interferon or somatostatin analogues such as Sandostatin LAR) recognizing that there is very meager literature (medical level evidence category 3) regarding the medical oncology management of recurrent meningioma4-6).

Mechanism of action and clinical applications of hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea functions as a cell cycle-specific urea analog that inhibits the enzyme ribonucleotide diphosphate reductase and interferes with DNA synthesis by reducing the available pool of deoxyribonucleotides27). Recent laboratory studies have also suggested another mechanism of tumor cell death, the induction of apoptosis32). The mechanism of hydroxyurea induced apoptosis remains unclear. It does not interact directly with DNA to cause strand breakage of adduct formation, which could up-regulate p53 activity and lead to apoptosis19,36). In the late 1950s, hydroxyurea underwent further preclinical testing by Stearns et al.35) and was noted to have significant activity in vitro against L1210 leukemia cells and various solid tumors. Currently the principal indication for using hydroxyurea is the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders, chronic myelogenous leukemia and polycythemia rubra vera in particular10,17,23).

Preclinical studies and clinical pharmacology of hydroxyurea in meningiomas

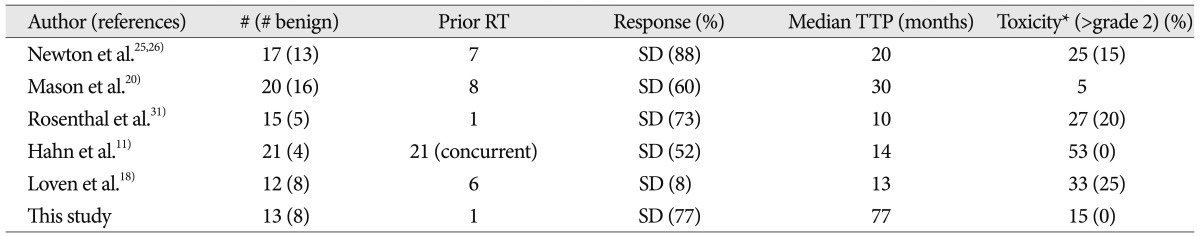

For meningiomas, hydroxyurea has constituted the primary medical therapy based on several studies and upon the initial report of its in vitro and in vivo activity by Schrell et al.32,33). Schrell et al. demonstrated in vitro that hydroxyurea, and oral chemotherapy with a variety of anti-tumoral effects was a potent inhibitor of cultured meningioma cells by inducing apoptosis of tumor cells32,33). Several subsequent clinical trials have demonstrated the in vivo efficacy of drug, with modest and acceptable toxicity seen in patients (Table 3)6). Hydroxyurea is administered orally and has excellent absorption and bioavailability from the gastrointestinal tract26). In cancer patients, oral bioavailability is very good, ranging from 80 to 100% in various studies10). In tissue level, hydroxyurea enters cells via passive diffusion, including the brain and cerebrospinal fluid2). At the many studies, hydroxyurea was administered orally and the dosage given was 20-30 mg/kg/day or 1000 mg/m2/day.

Table 3.

Hydroxyurea for recurrent meningioma

*National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria. # : numbers of patients, RT : radiotherapy, SD : stable disease, TTP : time to progression

Clinical studies of hydroxyurea in meningiomas

Mason et al.20) evaluated the activity of hydroxyurea over a 2-year treatment period (20-30 mg/kg/day) in a group of patients with recurrent or unresectable meningiomas. Newton et al.25,26) reported on the use of hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg/day) in several papers with overlapping cohorts. Rosenthal et al.31) treated 15 consecutive patients harboring recurrent or high-risk meningiomas with hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg/day). Hahn et al.11) recently reported the results of a pilot study using the combination of hydroxyurea and concurrent conformal radiation therapy. These studies showed that hydroxyurea has modest activity in patients with recurrent meningiomas. In contrast to the studies outlined above, other reports are less suggestive of the effectiveness of hydroxyurea against meningiomas. Loven et al.18) described 12 patients with unresectable meningiomas who received hydroxyurea at the usual dosing regimen over a 24-month observation period. Nine patients had progressive disease with a median time to progression of 13 months. Chamberlain and Johnston6) treated 60 patients who had WHO grade I recurrent meningioma with hydroxyurea (1000 mg/m2/day). There were no radiographic responses, 35% of patients had stable disease and 65% manifested progressive disease. The tumors in our series, as in the series of Newton et al.26) and Mason et al.20), were characterized by long periods of stability on long-term follow-up. Ten of 13 evaluable patients (76.9%) demonstrated SD, with a median TTP of 77 months. Six of these patients continue to remain stable on hydroxyurea. However, there was no CR or PR in our study. It seems that hydroxyurea has a positive impact on the behavior of enlarging benign meningiomas and the data provide preliminary support for its use in this group of patients, who often have limited therapeutic options. These data are important because more effective medical therapy is necessary for meningiomas. Although radiation therapy of meningiomas with standard external beam approaches or radiosurgery is often able to inhibit growth, the effect may not be durable22). Treatment with hydroxyurea appears to have delayed progression of the disease. Thus, hydroxyurea may provide a meaningful clinical benefit for recurrent meningiomas. The strength of this study is somewhat weakened by the fact that only 13 of patients had meningioma that were actively recurrent after the surgery at the time of hydroxyurea initiation.

Toxicity of hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea was well tolerated by most patients. The only consistent toxicity was hematological, with mild reduction of WBC. More severe (CTCAE grade III-IV) hematologic toxicity was not observed, and transfusions of growth factors were not required for any patients. In addition, there were no infections associated with the episodes of neutropenia. In patients with meningioma treated with hydroxyurea, the most commonly reported toxicity was hematological24). In the report by Schrell et al.32,33) when the white blood cell count fell below 3000/uL the dose was reduced for several day, with subsequent improvement. The cohort reported by Mason et al.20) had similar myelosuppressive toxicity, with anemia and neutropenia being most common abnormalities. NCI grades 2 and 3 toxicity were noted in eight patients. Five of these patients continued hydroxyurea treatment after a dose reduction, two continued without a change in dose, and one had to discontinue treatment. In the study by Newton et al.25) grade 1 and 2 toxicity included leucopenia in nine patients, thrombocytopenia in seven patients, and anemia in five patients. Minor dosage reductions of 250 to 500 mg/day were necessary in 11 patients with hematological toxicity. Non-hematological side effects included mild fatigue, bleeding of the gums, and constipation.

Treatment strategies of hydroxyurea in meningiomas

It is important that more effective medical therapy be developed for meningiomas. The use of chemotherapy might obviate the need for further surgical procedures in certain patients and offer another beneficial treatment option for patients whose tumors progress despite surgery and irradiation26). We think that could be considered an alternative therapy in patients with recurrent meningiomas following surgical resection. The current results suggest that hydroxyurea is active enough against meningiomas to stabilize tumors after failure of surgical resection. However, phase III controlled trials and Class I data will be needed to more accurately determine the response profile of hydroxyurea and how it compares with other therapies.

CONCLUSION

This study with extended follow-up period shows that hydroxyurea has modest activity against recurrent meningiomas and may induce durable stabilization of tumor in patients, including in patients whose tumors have recurred after multiple surgical resection and irradiation. We believe that hydroxyurea treatment is well tolerated and convenient, and could be considered an alternative treatment option in patients with recurrent meningiomas prior to reoperation or radiotherapy.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Yeungnam University research grants.

References

- 1.Adegbite AB, Khan MI, Paine KW, Tan LK. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:51–56. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.1.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blasberg RG, Patlak C, Fenstermacher JD. Intrathecal chemotherapy : brain tissue profiles after ventriculocisternal perfusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;195:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamberlain MC. Adjuvant combined modality therapy for malignant meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:733–736. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.5.0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ. Interferon-alpha for recurrent World Health Organization grade 1 intracranial meningiomas. Cancer. 2008;113:2146–2151. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Fadul CE. Recurrent meningioma : salvage therapy with long-acting somatostatin analogue. Neurology. 2007;69:969–973. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271382.62776.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain MC, Johnston SK. Hydroxyurea for recurrent surgery and radiation refractory meningioma : a retrospective case series. J Neurooncol. 2011;104:765–771. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condra KS, Buatti JM, Mendenhall WM, Friedman WA, Marcus RB, Jr, Rhoton AL. Benign meningiomas : primary treatment selection affects survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forbes AR, Goldberg ID. Radiation therapy in the treatment of meningioma : the Joint Center for Radiation Therapy experience 1970 to 1982. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:1139–1143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldsmith BJ, Wara WM, Wilson CB, Larson DA. Postoperative irradiation for subtotally resected meningiomas. A retrospective analysis of 140 patients treated from 1967 to 1990. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:195–201. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.2.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gwilt PR, Tracewell WG. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of hydroxyurea. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;34:347–358. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199834050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn BM, Schrell UM, Sauer R, Fahlbusch R, Ganslandt O, Grabenbauer GG. Prolonged oral hydroxyurea and concurrent 3d-conformal radiation in patients with progressive or recurrent meningioma : results of a pilot study. J Neurooncol. 2005;74:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-2337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaba SE, DeMonte F, Bruner JM, Kyritsis AP, Jaeckle KA, Levin V, et al. The treatment of recurrent unresectable and malignant meningiomas with interferon alpha-2B. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:271–275. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kallio M, Sankila R, Hakulinen T, Jääskeläinen J. Factors affecting operative and excess long-term mortality in 935 patients with intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:2–12. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyritsis AP. Chemotherapy for meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 1996;29:269–272. doi: 10.1007/BF00165657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JH, Kim OL, Kim SH, Bae JH, Choi BY, Cho SH. Hydroxyurea treatment for unresectable and uecurrent meningiomas. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2001;30:S120–S123. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth WT, Jr, Dennis LK, McGuire VM, Drangsholt MT, Koepsell TD. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Cancer. 1993;72:639–648. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<639::aid-cncr2820720304>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lori F, Lisziewicz J. Hydroxyurea : overview of clinical data and antiretroviral and immunomodulatory effects. Antivir Ther. 1999;4(Suppl 3):101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loven D, Hardoff R, Sever ZB, Steinmetz AP, Gornish M, Rappaport ZH, et al. Non-resectable slow-growing meningiomas treated by hydroxyurea. J Neurooncol. 2004;67:221–226. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000021827.85754.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin DS, Stolfi RL, Colofiore JR. Perspective : the chemotherapeutic relevance of apoptosis and a proposed biochemical cascade for chemotherapeutically induced apoptosis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:372–381. doi: 10.3109/07357909709039742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason WP, Gentili F, Macdonald DR, Hariharan S, Cruz CR, Abrey LE. Stabilization of disease progression by hydroxyurea in patients with recurrent or unresectable meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:341–346. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.2.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milosevic MF, Frost PJ, Laperriere NJ, Wong CS, Simpson WJ. Radiotherapy for atypical or malignant intracranial meningioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34:817–822. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miralbell R, Linggood RM, de la Monte S, Convery K, Munzenrider JE, Mirimanoff RO. The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of subtotally resected benign meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 1992;13:157–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00172765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navarra P, Preziosi P. Hydroxyurea : new insights on an old drug. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1999;29:249–255. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(98)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton HB. Handbook of brain tumor chemotherapy. Amsterdam, Boston: Elsevier Medical Publishers/Academic Press; 2006. pp. xvipp. 510–524. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newton HB, Scott SR, Volpi C. Hydroxyurea chemotherapy for meningiomas : enlarged cohort with extended follow-up. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:495–499. doi: 10.1080/02688690400012392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton HB, Slivka MA, Stevens C. Hydroxyurea chemotherapy for unresectable or residual meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2000;49:165–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1026770624783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newton HB, Turowski RC, Stroup TJ, McCoy LK. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and pharmacotherapy of patients with primary brain tumors. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:816–832. doi: 10.1345/aph.18353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noiri E, Masaki I, Fujino K, Tsuchiya M. Efficacy of a continuous syringe extraction method for monitoring hemodialysis ultrafiltrate. ASAIO J. 2000;46:461–463. doi: 10.1097/00002480-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollock BE, Stafford SL, Utter A, Giannini C, Schreiner SA. Stereotactic radiosurgery provides equivalent tumor control to Simpson Grade 1 resection for patients with small- to medium-size meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohringer M, Sutherland GR, Louw DF, Sima AA. Incidence and clinicopathological features of meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:665–672. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.5.0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenthal MA, Ashley DL, Cher L. Treatment of high risk or recurrent meningiomas with hydroxyurea. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:156–158. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrell UM, Rittig MG, Anders M, Kiesewetter F, Marschalek R, Koch UH, et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of unresectable and recurrent meningiomas. I. Inhibition of primary human meningioma cells in culture and in meningioma transplants by induction of the apoptotic pathway. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:845–852. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.5.0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrell UM, Rittig MG, Anders M, Koch UH, Marschalek R, Kiesewetter F, et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of unresectable and recurrent meningiomas. II. Decrease in the size of meningiomas in patients treated with hydroxyurea. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:840–844. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.5.0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22–39. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stearns B, Losee KA, Bernstein J. Hydroxyurea. A new type of potential antitumor agent. J Med Chem. 1963;6:201. doi: 10.1021/jm00338a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart BW. Mechanisms of apoptosis : integration of genetic, biochemical, and cellular indicators. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1286–1296. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.17.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]