Abstract

An efficient protocol for rapid in vitro clonal propagation of spine gourd (Momordica dioica Roxb.) genotype RSR/DR15 (female) and DR/NKB-28 (male) was developed through enhanced axillary shoot proliferation from nodal segments. Maximum shoot proliferation of 6.2 shoots per explant with 100 % shoot regeneration frequency was obtained from the female genotype on Murashige and Skoog’s (1962) medium supplemented with 0.9 μM N6-benzyladenine (BA) and 200 mg l-1 casein hydrolysate (CH). While from the male genotype the optimum shoot regeneration frequency (86.6 %) and 6.4 shoots per explant was obtained on MS medium supplemented with 2.2 μM BA. CH induced vigorous shoots, promoted callus formation, and proved inhibitory for shoot differentiation and shoot length, especially in explants from male genotype. Rooting was optimum on half-strength MS medium (male 92.8 %, female 74.6 %) containing 4.9 μM indole-3-butyric acid (IBA). Plantlets were transferred to plastic cups containing a mixture of cocopit and perlite (1:1 ratio) and then to soil after 2–3 weeks. 84 % female and 81 % male regenerated plantlets survived and grew vigorously in the field. Genetic stability of the regenerated plants was assessed using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD). The amplification products were monomorphic in the in vitro propagated plants and similar to those of mother plant. No polymorphism was detected revealing the genetic integrity of in vitro propagated plants. This micropropagation procedure could be useful for raising genetically uniform planting material of known sex for commercial cultivation or build-up of plant material of a specific sex-type.

Keywords: Momordica dioica, Dioecious, Axillary shoot proliferation, Micropropagation, Nodal explants, Genetic fidelity

Introduction

Spine gourd (Momordica dioica Roxb.) is a dioecious and perennial cucurbitaceous climber (Trivedi and Roy 1972) distributed throughout India, China, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan and Srilanka. Various plant parts are consumed in a variety of ways, viz., immature green fruits are cooked as vegetable, young leaves and flowers are also eaten. Fruits contain high amount of proteins, calcium, phosphorous, iron, and the highest amount of carotene (162 mg/100 g of edible portion) amongst the cucurbitaceous vegetables (Ram et al. 2001; Bharathi et al. 2007). In addition, this species is valued for several medicinal and curative properties (Ram et al. 2001; Ali and Shrivastava 1998).

This popular vegetable has high demand in market but still remain underutilized and underexploited (Bharathi et al. 2007; Ali et al. 1991) mainly due to its vegetative mode of propagation and dioecious nature. Conventional commercial propagation of spine gourd largely depends on tuberous roots (Nabi et al. 2002), followed by stem cuttings, and seeds. Commercial multiplication using the tuberous roots and stem cuttings are critically limited due to inadequate availability of tuberous roots and late availability of stem cuttings in fruiting season. Tuberous roots have low multiplication rate (Mondal et al. 2006) and occupies the valuable cultivable land until next planting season (Ram et al. 2001; Nabi et al. 2002). Stem cuttings containing 2–3 nodes from dark green vines of 2–3 months old plants are planted, but only 36 % of the plants sprout and survive (Ram et al. 2001). Difficulties in propagation by seeds are dormancy and unpredictable sex ratio in seedling progenies (Mondal et al. 2006; Ali et al. 1991). Male plants dominate natural populations and sex determination is possible only when the plants start flowering. Since fruits are the main edible portion of this species, which are harvested on female plants, it is desirable to have commercial fields with a large proportion of female plants. Accommodating 5–10 % male plants to act as pollinators in the field is imperative for good fruit set (Rasul et al. 2007).

As the conventional methods of spine gourd propagation impose several limitations for large-scale propagation of sex specific plants, an efficient clonal propagation method is a must. An in vitro propagation system offers unlimited availability of planting material early in the planting season. The application of micropropagation is well-established for rapid large-scale propagation of many crops and cucurbitaceous vegetables including Momordica species (Ahmad and Anis 2005; Sultana and Bari Miah 2003, Hoque et al. 2007). Attempts have also been made for in vitro propagation of M. dioica, wherein shoots were regenerated from callus cultures obtained from various explants (Hoque et al. 2007; Hoque et al. 2000; Hoque et al. 1995; Nabi et al. 2002; Karim and Ahmed 2010), but not from the nodal segments. Callus cultures, however, carries the risk of somaclonal variations which can seriously limit the broader utility of micropropagation systems. On the other hand, axillary bud proliferation method ensures clonal uniformity among the regenerants and, therefore, can subvert the limitations arising from callus cultures and organogenesis (Bopana and Saxena 2008). Any study on assessment of genetic fidelity of micropropagated spine gourd plants is not available. Moreover, there has not been any specific study on micropropagation of female and male genotypes of spine gourd. In this communication, we have established a simple and efficient method for large-scale in vitro propagation of spine gourd, to obtain clones of known sex-type and characteristics using nodal explants from in vitro-raised shoots. The genetic integrity of the in vitro regenerated spine gourd plants was checked using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis.

Materials and methods

Plant material and surface sterilization

The plant material consisted of vine cuttings taken from a female genotype RSR/DR15 and a male genotype DR/NKB-28 of spine gourd; segments having 5–6 nodes were collected from the research farm of Indian Institute of Vegetable Research, Varanasi, India. These vine cuttings were treated with a solution containing 0.75 % (w/v) bavistin (a systemic fungicide) and 0.50 % (v/v) Tween-20. Vine cuttings were washed thoroughly in distilled water and single node vine pieces of about 4–5 cm were excised. These nodal segments were soaked in 1 % Tween-20 containing 0.2 % (w/v) streptomycin (a broad spectrum antibiotic) (Himedia, Mumbai, India) for 20 min with vigorous shaking at 180 rpm followed by single rinse in distilled water. The explants were then surface sterilized by treating with a solution of 5 % (v/v) sodium hypochlorite containing 1 % Tween-20 for 10 min on continuous shaking under laminar hood, rinsed twice in sterile double distilled water, followed by 0.1 % (w/v) mercuric chloride treatment for 3 min. Finally, the explants were rinsed four times with sterile double distilled water, blotted dry and trimmed from both ends to about 3 cm and cultured.

Culture medium and conditions

The full- and half-strength MS (Murashige and Skoog 1962) basal medium (growth regulator-free MS medium supplemented with 3 % (w/v) sucrose), solidified with 0.5 % (w/v) agar (Hi Media, Mumbai, India) was used; pH of medium was adjusted to 5.8 and 15 ml medium was dispensed into 25x150 mm culture tubes before sterilization. The medium was autoclaved at 121 °C and 1.05 kg cm−2 of pressure for 20 min. Phytohormones and casein hydrolysate (CH) was added prior to autoclave. Cultures were incubated at 25 ± 2 °C under 16 h photoperiod of 50 μmol m−2 s−1 irradiance provided by cool-white fluorescent tubes (40 W, Philips, India).

Culture initiation

Surface sterilized explants were cultured separately on half- and full-strength MS basal medium. After developing the shoots of 8–10 cm, single node explants were excised from these in vitro-grown primary shoots and subcultured again onto MS basal medium at 30 days interval, in order to increase the stock material for the experiments and to maintain in vitro mother shoot stocks of known sex type.

Shoot multiplication

Nodal explants containing single dormant axillary bud were excised from the shoot stocks and cultured on MS basal and its combinations with different concentrations (0.9–22.2 μM) of N6-benzyladenine (BA) augmented with or without 200 mg l−1 CH, to generate twelve different treatments (Table 2). The frequency of shoot response, shoots per explant and length of the shoots were recorded at the end of the 30 days culture period.

Table 2.

Effects of concentrations of BA, and casein hydrolysate on in vitro shoot proliferation from nodal explants of M. dioica after 30 days

| BA (μM) | CH | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoot response (%) | Number of shoots per explant (mean ± SE) | Average shoot height (cm ± SE) | Shoot response (%) | Number of shoots per explant (mean ± SE) | Average shoot height (cm ± SE) | ||

| – | − | 87.0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 80.4 | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| – | + | 85.1 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 74.9 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| 0.9 | − | 100.0 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 100.0 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 8.8 ± 0.9 |

| 0.9 | + | 89.0 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 100.0 | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.4 |

| 2.2 | − | 86.6 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 98.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| 2.2 | + | 87.5 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 98.2 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| 4.4 | − | 73.6 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 72.7 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| 4.4 | + | 69.6 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 62.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| 8.9 | − | 60.6 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 83.7 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| 8.9 | + | 31.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 70.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

SE: standard error

Each mean is based on three replicates, each of which consisted of 12–15 culture tubes. Data were recorded after 30 days.

Root induction

To study the rooting response, individual shoot of approximately 1 cm was excised at the end of a 30 days proliferation period from shoot clusters and planted vertically on rooting media. To achieve optimal rooting, MS full-strength and MS half-strength supplemented with different levels of 1.0–24.6 μM indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) were tested (Table 3). After 40 days of culture on the rooting medium the frequency of rooted shoots, total number of roots, and root length for each explant were recorded.

Table 3.

Effects of concentrations of IBA and MS medium strength on root induction from in vitro proliferated shoots of M. dioica after 40 days

| MS media strength | IBA (μM) | Male | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root response (%) | Number of roots (mean ± SE) | Average root length (cm ± SE) | Root response (%) | Number of roots (mean ± SE) | Average root length (cm ± SE) | ||

| H | – | 38.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 34.0 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| F | – | 30.6 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 12.9 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.5 |

| H | 1.0 | 27.4 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 36.1 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

| F | 1.0 | 14.4 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 26.4 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| H | 2.5 | 64.3 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 76.2 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.7 |

| F | 2.5 | 32.2 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 40.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| H | 4.9 | 92.8 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 74.6 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| F | 4.9 | 49.5 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 69.3 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.9 |

| H | 9.9 | 97.1 | 8.6 ± 1.8 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 76.4 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| F | 9.9 | 47.4 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 25.0 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| H | 24.6 | 67.5 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.0 | 73.0 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| F | 24.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

SE: standard error; H: half strength; F: full strength

Each mean is based on three replicates, each of which consisted of 12–15 culture tubes. Data were recorded after 40 days.

Acclimatization

Plantlets with well-developed roots were removed from the rooting medium and washed gently under running tap water to remove all traces of medium attached to the roots. They were transferred to plastic cups containing 1:1 mixture of sterilized cocopit and perlite, and covered with polythene bags to maintain humidity. The potted plants were first time irrigated with 0.2 % bavistin in tap water and thereafter only tap water. They were maintained inside a culture room at 25 ± 2 °C for 16 h/day illumination with cool-white fluorescent light (50 μmol m−2 s−1). After a week, the polythene bags were gradually removed over a period of 3 days. The plants were kept in the culture room for another 8 days. After 18 days of acclimatization, the plantlets were potted in soil and transferred to a glass house (16 h light/8 h dark cycle at 24–28 °C). The ex vitro establishment rate was assessed as the percentage of acclimatized plants that survived after 8 weeks of transplanting.

Assessment of genetic fidelity using RAPD analysis

Genetic fidelity between the mother plant and randomly selected in vitro regenerated plants established in soil was assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based RAPD analysis. Genomic DNA was isolated from juvenile leaves of the female and male mother plants and in vitro propagated plants by Purelink Plant DNA Purification kit (Invitrogen, USA). The concentration of DNA was determined by a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer 2380) and quality of genomic DNA was checked following electrophoresis on 0.8 % agarose gel. RAPD assay was performed using the 16 random decanucleotide primers (Table 1). PCR was performed in a volume of 25 μl reaction mixture containing 1 μl template DNA (80 ng), 2.5 μl 10 x PCR buffer, 1 μl of dNTPs (25 mM), 1.5 μl MgCl2 (1.5 mM), 1 μl random primer (10 pM), 0.5 μl Taq polymerase (three units) and 17.5 μl, sterile distilled water. DNA amplification was carried out in a DNA thermal cycler (Biorad, USA). The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation for 5 min at 94 °C, then 38 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 94 °C, 1 min annealing at 33 °C, and 1 min extension at 72 °C with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis was carried out. Amplification with each primer was repeated twice to confirm reproducibility of the results. The amplified samples were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1.5 % agarose gels using Tris–Acetic acid–Ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid buffer and stained with ethidium bromide. The number of amplified products was recorded using a gel documentation system (AlphaImagerTM 3400).

Table 1.

The nucleotide sequences of primers used for RAPD analysis

| Primer | 5′-3′ | Primer | 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPK-02 | GTCTCCGCAA | OPL-01 | GGCATGACCT |

| OPK-03 | CCAGCTTAGG | OPL-02 | TGGGCGTCAA |

| OPK-05 | TCTGTCGAGG | OPL-03 | CCAGCAGCTT |

| OPN-01 | CTCACGTTGG | OPL-04 | GACTGCACAC |

| OPN-02 | ACCAGGGGCA | OPL-20 | TGGTGGACCA |

| OPN-03 | GGTACTCCCC | OPZ-11 | CTCAGTCGCA |

| OPN-16 | AAGCGACCTG | OPZ-17 | CCTTCCCACT |

| OPO-06 | CCACGGGAAG | OPZ-19 | GTGCGAGCAA |

Statistical data analysis

Experiments were set up in a Randomized Block Design (RBD) and each experiment had three replicates. The number of cultures (nodal explants for shoot proliferation and shoots for root induction) per replicate varied from 12–15. The frequency of shoot regeneration was calculated as the percent of nodal explants showed bud break out of total number of explants inoculated in a particular treatment. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) appropriate for the design was carried out using SPSS 11.5 to detect the significance of differences among the treatment means. The treatment means were compared using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a 5 % probability level.

Results and discussion

Shoot initiation

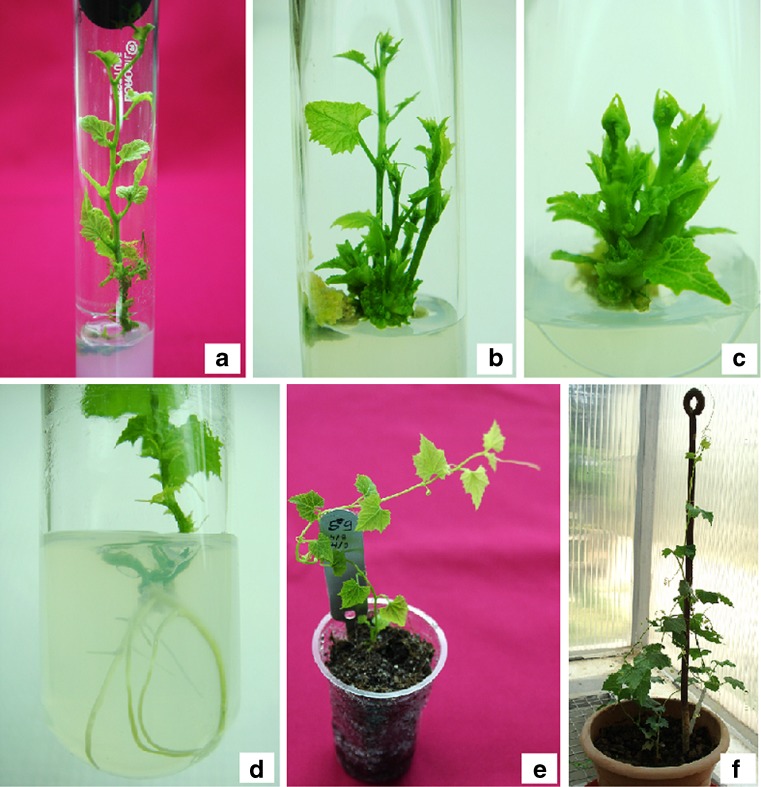

Culture initiation of spine gourd genotypes from field explants proved rather difficult due to heavy fungal contamination and sensitivity of explants to the reagents such as sodium hypochlorite and mercuric chloride solution. The disinfected explants cultured on half-strength MS basal medium had less contamination rate than that of full-strength MS basal medium (data not shown). Disinfected explants produced one shoot of 8–10 cm after 6 weeks of culture, demonstrating a successful establishment of shoot cultures (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

In vitro propagation of Momordica dioica Roxb.: a Axillary shoot formed from the male genotype nodal segment during culture initiation of M. dioica on half-strength MS medium; b Proliferation of axillary shoots from female genotype nodal segment on MS medium supplemented with 0.9 μM BA and 200 mg l−1 casein hydrolysate; c Axillary shoot proliferation from male genotype nodal explant on MS medium supplemented with 2.2 μM BA; d Root regenerated from shoot cultured on half-strength MS medium containing 4.9 μM IBA; e In vitro regenerated plantlet of M. dioica transferred into plastic cup; f Acclimatized plant transplanted into soil in the glasshouse conditions

Shoot proliferation

The nodal segments did not show axillary bud proliferation on MS basal or MS medium with 200 mg l−1 CH, and only developed into a single shoot. The shoots from male clones were 60 % or more taller than the shoots from female clones on MS basal medium (Table 2). In the present study, BA was the only plant growth regulator (PGR) used for axillary shoot proliferation. The combinations of BA and NAA have been reported for spine gourd regeneration (Hoque et al. 1995; Nabi et al. 2002), but these produce adventitious shoots and promoted callus formation in spine gourd and many other plants. A varying degree of shoot bud differentiation and proliferation was observed (Table 2) at lower BA concentrations (0.9, 2.2 μM), whereas a higher BA concentration led to callus formation. With an increase in the BA concentration, frequency of responding explants decreased (Table 2) and frequency of callus formation increased. There was yellowish callus formation at 4.4 μM BA, and beyond 4.4 μM BA a number of ill-defined buds were observed.

CH at a concentration of 200 mg l−1 has been reported to improve shoot proliferation of cucurbitaceous vegetable Cucumis sativus L. (Ahmad and Anis 2005). In the present study, CH along with BA induced vigorous and healthy shoots but promoted axillary buds to develop whitish fragile callus at the higher concentrations of BA. CH substantially increased the number of shoots induced from female nodal explants cultured on 0.9 μM BA supplemented MS medium only (Table 2). However, CH had inhibitory effect on shoot height of both sexes on MS basal and 0.9 μM BA supplemented MS medium. In addition, CH reduced the axillary shoot proliferation response of the male genotype when augmented with 8.9 μM BA. Inhibitory effect of CH was reported previously on shoot differentiation in both sexes of jojoba, especially in male explants (Prakash et al. 2003).

The highest number of shoots (6.2 shoots per explant) from the female genotype was obtained on MS medium supplemented with 200 mg l−1 CH and 0.9 μM BA, with 100 % response and average shoot length of 3.4 cm (Fig. 1b). On contrary, male genotype node segments yielded the highest number of shoots (6.4 shoots per explant) on MS medium containing 2.2 μM BA alone, with a proliferation rate of 86.6 % and average shoot length of 2.0 cm (Fig. 1c). Earlier, the combination of BA (1.0 μM) with CH (200 mg l−1) was reported best for multiple shoot induction for Cucumis sativus L. (Ahmad and Anis 2005) with 100 % shoot regeneration from nodal segments. Differential morphological responses from nodal explants of male and female jojoba clones on media supplemented with different cytokinins (Agrawal et al. 1999) and CH (Prakash et al. 2003) has also been observed.

Shoot regeneration rate of 100 % was obtained from the spine gourd nodal segments in the present study. Earlier, the highest reported shoot regeneration rate of 88 % for spine gourd was achieved by Hoque et al. (1995) from hypocotyls with 8.8 shoots per explant. Karim and Ahmed (2010) obtained 5.1 shoots per nodal explant of M. dioica by somatic embryogenesis. In the present study, the highest number of shoots per explant was 6.4 from the male genotype. A higher shoot regeneration potential of M. dioica was reported from female embryo explants (76.4 %, 22.44 shoots per explant) (Hoque et al. 2007), and 25.3 adventitious shoots per cotyledon (Nabi et al. 2002). However, none of them reported a high axillary shoot proliferation from nodal segments.

Multiplication of shoot cultures

Male and female shoot clusters and nodal segments from the in vitro formed shoots, developed on MS medium containing 2.2 μM BA for male and 200 mg l−1 CH augmented 0.9 μM BA for female, were subcultured on the same medium after every 30 days. A delay of 15 to 20 days in subculturing of shoots did not pose any problem with regard to the multiplication rate or the quality of shoots obtained. Four to seven shoots per explants formed during the three subsequent culture passages on MS medium with 2.2 μM BA for male, and 200 mg l−1 CH augmented MS medium with 0.9 μM BA for female sex-type. Small basal callus, however, developed on some explants during repeated subculturing. The shoot clusters when cultured on PGR free MS basal medium showed shoot elongation.

Root induction and acclimatization

Spontaneous rooting occurred at very low rate (12.9–38.3 %) on PGR-free full- and half-strength MS medium. It is a common practice to transfer shoots from a high strength media to less concentrated solutions to induce rooting. The concentration of nitrogen ions needed for root formation is much lower than for shoot formation and growth (Driver and Suttle 1987). In many species, rooting frequency was higher when shoots were rooted on low strength MS medium (Andrade et al. 1999; Purohit et al. 1994).

In the preliminary experiments conducted, NAA supplemented MS medium induced basal callus formation (data not shown). The rooting treatments consisted of full- and half-strength MS medium supplemented with 0.0 to 24.6 μM IBA (Table 3). In previous reports also, IBA proved to be the best for root regeneration of M. dioica (Hoque et al. 2007; Hoque et al. 1995; Nabi et al. 2002; Karim and Ahmed 2010) and had marked effect on rooting of many species such as Centella asiatica (Tiwari et al. 2000; Banerjee et al. 1999), and Teucrium fruticans L. (Frabetti et al. 2009).

MS medium strength had significant impact on frequency of root induction, number of roots, and root length. IBA supplemented half-strength MS medium was approximately two-fold better than IBA supplemented full-strength MS medium for rooting response of spine gourd shoots (Table 3). Moderate to profuse rooting (40–97 %) occurred from shoot explants cultured in all concentrations of IBA with varying average number of roots and root length. Optimum shoot growth was observed on 4.9 μM IBA supplement full- and half-strength MS medium.

Basal callus formed on half- and full-strength MS medium containing 9.9 to 24.6 μM IBA. Size of the callus increased with the higher concentrations of IBA. Smaller callus formed on half-strength MS than full-strength (data not shown). Rooting frequency increased with an increase in the concentration of IBA upto 9.9 μM. Although better rooting was observed on 9.9 μM IBA supplemented half-strength MS medium, but since it associated with callus formation, the optimal rooting medium for female and male M. dioica sex-type was half-strength MS basal with 4.9 μM IBA (Fig. 1d). On this medium, a rooting frequency of 74.6 % was observed from female shoots after 40 days of culture, with a mean of 4.6 roots per shoot and 4.6 cm average root length (Table 3). The optimal rooting response for male shoots was 92.8 %, 3.8 roots per shoot on an average, with a mean root length of 4.1 cm. The highest number of roots (2.8 roots per shoot) of spine gourd with mean root length of 1.89 cm has been earlier reported (Nabi et al. 2002) in 1.0 μM IBA. In the present study, the spine gourd roots were two fold longer on 1.0 μM IBA, and number of roots per shoots retained the higher value (4.6).

The rooted plants of shoot length of 6–8 cm were transferred from culture tubes into plastic cups (Fig. 1e) containing mixture of cocopit and perlite with 81 % survival of male and 84 % survival of female plants. This is close to highest reported 85 % survival of female x female clones of M. dioica (Hoque et al. 2007). The twenty five acclimatized plants of each sex-type were transferred to soil. Among them twenty two male and twenty three female plants were successfully established in soil (Fig. 1f), and survived for six months. The established plants showed normal flowering and fruit set, and no morphological abnormalities were found when compared with donor plants.

Assessment of genetic fidelity of in vitro propagated plants

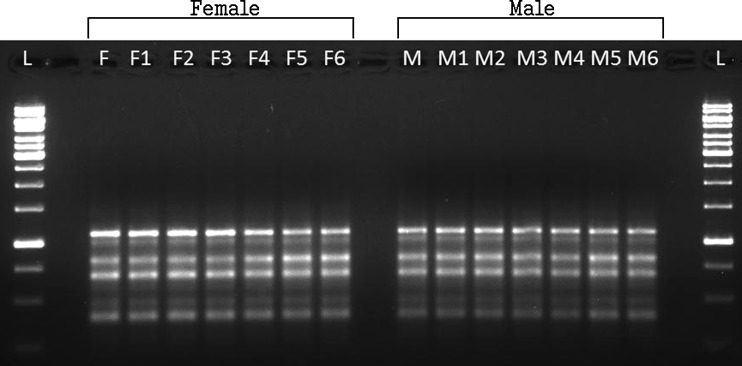

Under the optimized PCR conditions, all the tested primers produced resolvable, reproducible and scorable bands. Sixteen random primers were used for the RAPD analysis (Table 1). The number of amplified bands produced by each primer ranged from 3 to 9, i.e., 6 bands from OPK-02, 8 bands from OPK-03, 7 bands from OPK-05, 5 bands from OPN-01, 4 bands from OPN-02, 9 bands from OPN-03, 5 bands from OPN-16, 6 bands from OPL-20, 3 bands from OPO-06, 7 bands from OPL-01, 7 bands from OPL-02, 8 bands from OPL-03, 5 bands from OPL-04, 3 bands from OPZ-11, 8 bands from OPZ-17, and 6 bands OPZ-19. RAPD profile obtained through amplification of genomic DNA of the in vitro grown plants was similar in all respects. All the 16 primers produced monomorphic bands confirming the genetic homogeneity of the in vitro-raised plants. Figure 2 shows RAPD amplification patterns obtained with the primer OPL-20. Monomorphic banding pattern was observed for all the amplified band classes across the female and male regenerants with all the tested primers. No RAPD polymorphism was observed in the micropropagated plants. In addition, the sixteen tested primers did not reveal any sex-specific differences between the two clones. The results of this molecular study revealed that the micropropagated plants were genetically identical and no variation was induced during clonal propagation. RAPD has been proven to be a suitable molecular technique to detect the variation that is induced or occurs during in vitro regeneration of plant species (Shu et al. 2003). RAPD is becoming a widely employed method in the detection of genetic diversity because it has the advantage of being technically simple, quick to perform and requires only small amounts of DNA (Ceasar et al. 2010). Many investigators have reported genetic stability of several micropropagated plants, viz., chestnut rootstock hybrid (Carvalho et al. 2004), Prunus dulcis (Martins et al. 2004), banana (Venkatachalam et al. 2007), etc. using RAPD. As observed, our result clearly indicates the genetic integrity and true-to-type nature of the in vitro regenerated plants.

Fig. 2.

RAPD profile of in vitro regenerated plants of spine gourd generated by primer OPL-20. L; 1-Kb DNA ladder, F; female mother plant, F1-F6; in vitro regenerated female plants, M; male mother plant, M1-M6; in vitro regenerated male plants

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report for differential axillary shoot proliferation and micropropagation of the female and male spine gourd genotypes from nodal explants. Adventitious shoot proliferation can lead to somaclonal variation and changes in phenotype which is undesirable in commercial clonal propagation. Our method allows shoot induction and proliferation in 30 days and the young plants can be transferred to soil in eight-nine weeks thereafter. This protocol thus provides a prolific, rapid and sex specific propagation system that has opened possibilities for commercial production of female and male plants separately, and ex situ conservation of an underutilized vegetable crop like spine gourd.

References

- Agrawal V, Prakash S, Gupta SC. Differential hormonal requirements for clonal propagation of male and female jojoba plants. In: Altman A, Ziv M, Izhar S, editors. Current science and biotechnology in agriculture: plant biotechnology and in vitro biology in the 21st century. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Okubo H, Fujii T, Fujieda K. Techniques for propagation and breeding of kakrol (Momordica dioica Roxb.) Sci Hortic. 1991;47(3–4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/0304-4238(91)90017-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Shrivastava V. Characterization of phytoconstitutents of the fruits of Momordica dioica. J Pharamaceutical Sci. 1998;60:287–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad N, Anis M. In vitro mass propagation of Cucumis sativus L. from nodal segments. Turk J Bot. 2005;29:237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LB, Echeverrigaray S, Fracaro F, Pauletti GF, Rota L. The effect of growth regulators on shoot propagation and rooting of common lavender (Lavandula vera DC) Plant Cell Tiss Org Cult. 1999;56(2):79–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1006299410052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Zehra M, Kumar S. In vitro multiplication of Centella asiatica, a medicinal herb from leaf explants. Curr Sci. 1999;76:147–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bharathi LK, Naik G, Singh HS, Dora DK. Spine gourd. In: Peter KV, editor. Underutilized and underexploited horticultural crops. New Delhi: New India Publishing; 2007. pp. 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Bopana N, Saxena S. In vitro propagation of a high value medicinal plant: Asparagus racemosus Willd. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol—Plant. 2008;44:525–532. doi: 10.1007/s11627-008-9137-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho LC, Goulao L, Oliveira C, Goncalves JC, Amancio S. RAPD assessment for identification of clonal identity and genetic stability of in vitro propagated chestnut hybrids. Plant Cell Tiss and Org Cult. 2004;77:23–27. doi: 10.1023/B:TICU.0000016482.54896.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceasar SA, Maxwell SL, Prasad KB, Karthigan M, Ignacimuthu S. Highly efficient shoot regeneration of Bacopa monnieri L. using a two-stage culture procedure and assessment of genetic integrity of micropropagated plants by RAPD. Acta Physiol Plant. 2010;32:443–452. doi: 10.1007/s11738-009-0419-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driver JA, Suttle GR. Nursery handling of propagules. In: Bonga JM, Durzan DJ, editors. Cell and tissue culture in forestry. Dordrecht: The Netherlands; 1987. pp. 320–335. [Google Scholar]

- Frabetti M, Gutiérrez-Pesce P, Mendoza-de Gyves E, Rugini E. Micropropagation of Teucrium fruticans L., an ornamental and medicinal plant. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol—Plant. 2009;45:129–134. doi: 10.1007/s11627-009-9192-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque A, Islam R, Joarder OI. In vitro plantlets differentiation in kakrol (Momordica dioica Roxb.) Plant Tiss Cult. 1995;5(2):119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque A, Islam R, Arima S. High frequency plant regeneration from cotyledon-derived callus of Momordica dioica (Roxb.) Willd. Phytomorphology. 2000;50:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque A, Hossain M, Alam S, Arima S, Islam R. Adventitious shoot regeneration from immature embryo explant obtained from female × female Momordica dioica. Plant Tiss Cult Biotech. 2007;17(1):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Karim MA, Ahmed SU. Somatic embryogenesis and micropropagation in teasle gourd. Int J of Environ Sci and Dev. 2010;1(1):10–14. doi: 10.7763/IJESD.2010.V1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins M, Sarmento D, Oliveira MM. Genetic stability of micropropagated almond plantlets as assessed by RAPD and ISSR markers. Plant Cell Rep. 2004;23:492–496. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0870-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal A, Ghosh GP, Zuberi MI. Phylogenetic relationship in different kakrol collections of Bangladesh. Pakistan J Biol Sci. 2006;9(8):1516–1524. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2006.1516.1524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi SA, Rashid MM, Al-Amin M, Rasul MG. Organogenesis in teasle gourd (Momordica dioica Roxb.) Plant Tiss Cult. 2002;12(2):173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Agrawal V, Gupta SC. Influence of some adjuvants on in vitro clonal propagation of male and female jojoba plants. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol—Plant. 2003;39:217–222. doi: 10.1079/IVP2002369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit SD, Dave A, Kukda G. Micropropagation of safed musli (Chlorophytum borivilianum), a rare Indian medicinal herb. Plant Cell Tiss Org Cult. 1994;39(1):93–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00037596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ram D, Banerjee MK, Pandey S, Srivastava U. Collection and evaluation of Kartoli (Momordica dioica Roxb. Ex. Willd.) Indian J Plant Genet Resour. 2001;14:114–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul MG, Hiramatsu M, Okubo H. Genetic relatedness (diversity) and cultivar identification by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers in teasle gourd (Momordica dioica Roxb.) Sci Hortic. 2007;111:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2006.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shu QY, Liu GS, Qi DM, Chu CC, Liu J, Li HJ. An effective method for axillary bud culture and RAPD analysis of cloned plants in tetraploid black locust. Plant Cell Rep. 2003;22:175–180. doi: 10.1007/s00299-003-0661-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana RS, Bari Miah MA. In vitro propagation of karalla (Momordica charantea Linn.) from nodal segment and shoot tip. J Biol Sci. 2003;3(12):1134–1139. doi: 10.3923/jbs.2003.1134.1139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari KN, Sharma NC, Tiwari V, Singh BD. Micropropagation of Centella asiatica (L.), a valuable medicinal herb. Plant Cell Tiss and Org Cult. 2000;63:179–185. doi: 10.1023/A:1010690603095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi RN, Roy RP. Cytological studies in some species of Momordica. Genetica. 1972;43:282–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00123635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam L, Sreedhar RV, Bhagyalakshmi N. Micropropagation in banana using high levels of cytokinins does not involve any genetic changes as revealed by RAPD and ISSR markers. Plant Growth Regul. 2007;51:193–205. doi: 10.1007/s10725-006-9154-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]