Abstract

The effects of exogenous application of plant growth regulators (PGRs) like kinetin and a morphactin were investigated in leaf discs obtained from detached senescent Raphanus sativus L. Chetki long leaves under continuous light with fluorescent tube of 8.12 μmol photon m-2 s-1 PFD. Senescence induced changes were characterized by a gradual breakdown of chlorophylls, carotenoids and protein whereas, POD (peroxidase) and protease activity; and total sugars revealed an increment. Application of kinetin (KN) and a morphactin (MOR; chlorflurenol methyl ester-CME 74050) found to be effective in senescence delay, by minimizing breakdown of chlorophylls and carotenoids; and by bringing down peroxidase and protease activity, and sugar accumulation. Although both PGR’s were able to minimize senescence, their higher concentration found to be more effective than the lower one.

Keywords: Enzymatic activity, Kinetin, Morphactin, Senescence, Raphanus sativus

Introduction

Alterations in the duration, intensity, quality and interaction of light with other environmental variables bring about important changes in excised leaves (Hodges and Forney 2000). Besides light, a number of plant growth regulators (PGRs) such as kinetin (KN), morphactin (MOR), and salicylic acid (SA) are well known for postponing senescence. Morphactins are a novel group of synthetic plant growth regulators which modify growth and development (Schneider 1970) and also delay senescence (Nooden and Nooden 1985). Cytokinins also regulate a number of growth and developmental processes in plants, such as stimulating cell division, maintaining plant vigor and delaying plant senescence (Gan and Amasino 1997; Robson et al. 2004). Consequently the main objective of this study was to evaluate role of light and two PGRs viz. KN and MOR in the regulation of leaf senescence as fewer reports are available indicating how MOR application can tackle the problem of short shelf life being experienced by all green leafy vegetables including radish, and to compare with that of KN. Short shelf life is the major problem faced by all the green leafy vegetables.

Material and methods

Seeds of Raphanus sativus L.cv. Chetki long were germinated and plants were grown in experimental cage of University botanical garden, Kurukshetra. The length, breadth, and height of the cage were 12 m × 12 m × 2.5 m respectively. Seeds were sown inside cage in nine experimental plots, each one with an area of 1 × 3 m2. Experimental beds were prepared with typical garden soil as per common agronomical practice. During growth of plants average low and high temperatures were 11 °C and 24 °C respectively whereas RH values were 94 % and 53 % during morning and afternoon hours. Plants were irrigated twice a week. After about two months of sowing, mature radish leaves were collected, washed and dried in the folds of blotting paper during morning. Punched out leaf discs were floated on 6 ml of two concentrations each of KN (0.375 μM; pH-5.50 and 3.75 μM; pH-5.30) and MOR (3.64 μM; pH-6.27 and 36.4 μM; pH-5.77) placed in Corning Petri dishes of 9 cm2 diameter and incubated at 24 ± 2 °C. Each Petri dish was lined with Whatmann No. 1 filter paper with 55 leaf discs, each one having an area of 0.6 cm2. Control sets were maintained in distilled water. Samples were collected at 0, 2, 4 and 6 day during light of 8.12 μmol photon m-2 s-1 photon flux density (PFD). Three replicates were used for each biochemical analysis.

Chlorophylls and carotenoids estimation

The amount of samples used for an extraction ranged from 50–100 mg depending upon availability and requirements. Chilled 80 percent acetone (AR grade) and a pinch of CaCO3 were used during extraction and the absorbance was recorded at 480, 510, 645, and 663 nm using an UV-vis spectrophotometer (Specord-205 Analytik Jena, Germany). The pigments were estimated by the formulae and method of Arnon (1949) and Holden (1965).

POD activity

The total peroxidase activity was measured by the method of Maehly (1954) using guaiacol and H2O2. Breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by peroxidase with guaiacol as hydrogen donor, is determined by measuring its activity (due to formation of tetraguaiacol) on the basis of color development at 420 nm. Specific activity of peroxidase was expressed as mg-1protein min-1.

Protein estimation and protease activity

Protein was estimated by the method of Bradford (1976) using coomassie brilliant blue G-250 dye. The ninhydrin method was followed for the estimation of protease activity originally described by Yemm and Cocking (1955) and modified by Reimerdes and Klostermeyer (1976). The protease activity was expressed in μM lysine equivalent per 100 mg weight of the sample per hour.

Total soluble sugar

The total soluble sugar was measured following the method of Hart and Fisher (1971). Amounts of reducing and non reducing sugars were calculated against a standard curve of glucose.

Three replicates were used for each biochemical analysis.

Result and discussion

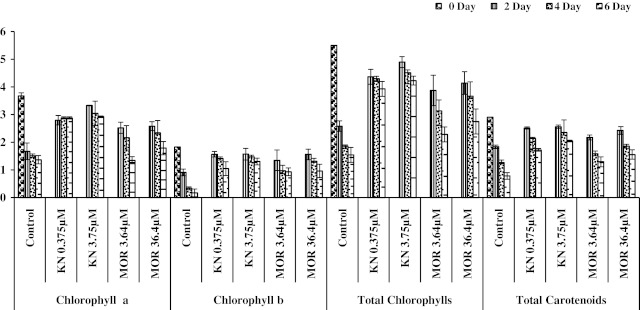

Results of Raphanus sativus leaf discs during 2, 4 and 6-day as incorporated in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 revealed a regular reduction in the amount of chlorophylls, carotenoids and proteins; increased activities of POD and protease and rise in total soluble sugars during progress of senescence. Figure 1 shows a pronounced degradation of chlorophylls and carotenoids in leaf discs of Raphanus sativus. Chlorophyll breakdown is the most typical symptom of leaf senescence (Grover and Mohanty 1993; Smart 1994). In the present study comparison of chl a and chl b values revealed much higher breakdown of the former than the latter at 2- day but the reverse trend was seen in most of the cases when leaf discs were analysed after 4 and 6-day (Fig. 1). Chl a and chl b do not generally degrade at the same rate, various trends in the chl a/b ratio have been observed with different plant species under various senescence conditions (Hidema et al. 1992; Lu and Zhang 1998a, b). However, degradation of chl a during senescence is well documented; chlorophyllase is the first enzyme to open the porphyrin macrocycle ring of chl a. It is assumed that chl b is converted to chl a before degradation (Matile et al. 1996). Leaf discs having MOR applications showed greater reduction in chl a. Both the PGRs used in this study markedly reduced the degradation of all pigments as evident from the per cent changes. Higher concentration of KN and MOR was more effective than the lower one (Fig. 1). It has been demonstrated that cytokinin treatment reduced activity of chlorophyllase, Mg-dechelatase and peroxidase- linked chlorophyll bleaching in broccoli florets during postharvest stage (Costa et al. 2005). Therefore a similar mechanism is proposed in the present research for chl retention. Cytokinins have the ability to suppress chlorophyll loss in leaves during senescence process (Arteca 1996). In the present study, per cent degradation of total chlorophyll and carotenoid during 6 day in control was about 72 and 73 respectively, however values after 2 and 4 day clearly indicate greater changes in the former than latter. Carotenoid degradation during senescence was much higher in control whereas in treated leaf discs remarkable reduction in the losses has been found. At 2-day stage in light, reduction in the total chlorophyll content was higher than carotenoids. Cytokinins increase the synthesis of carotenoids, which are known to protect the reaction centers from the detrimental effects of light and oxygen too (Chernyad’s 2000). Degradation of the chloroplast components (chlorophylls, proteins) and a decline in the photosynthetic function are usually slower under light conditions (Kar et al. 1993; Chang and Kao 1998). Retardation in degradation of chlorophyll or promotion of its synthesis with kinetin in leaves has been also suggested by Kumar (1990) and Rao (1990) in Cajanus cajan. Exogenous treatment of cytokinin results in delayed leaf senescence. Moreover, endogenous levels of cytokinins decline in parallel with the progression of senescence thereby illustrating the control exercised by that hormone. A striking example of this suppressive effect has been observed in transgenic tobacco and lettuce plants that expresses the ipt gene, an Agrobacterium-originated cytokinin biosynthesis gene, under the control of the senescence specific SAG12 promoter. Transgenic plants show markedly delayed leaf senescence (Gan and Amasino 1995; Mckenzie et al. 1998; McCabe et al. 2001).

Fig. 1.

Chlorophyll a, Chlorophyll b, Total Chlorophyll and Total Carotenoids (mg/100 mg dry wt.) in Raphanus sativus under low light

Fig. 2.

Peroxidase activity (mg-1protein min-1) in Raphanus sativus under low light

Fig. 3.

Protein content (mg/100 mg dry wt.), Protease activity (μM Lysine equivalent/100 mg dry wt hr-1) and in Raphanus sativus under low light

Fig. 4.

Reducing sugars, Non reducing sugars and Total sugars (mg/100 mg dry wt.) in Raphanus sativus under low light

In the present study, POD activity was markedly decreased when PGR treatments were given to delay senescence with respect to control. Samples collected after 4 and 6-day exhibited much higher differences with respective controls and treated samples. For reducing POD activity, best result was noticed with KN, followed by MOR treatments; in both the cases, higher concentration performed better (Fig. 2). Effective role of KN to reduce POD activity and delay senescence was noticed earlier with leaves of C. cajan (Rao and Mukherjee 1990). POD is one of the enzymes predominantly found in the plants which bleach chlorophyll in presence of H2O2 and certain phenolics (Ponmeni and Mukherjee 1997). Primary function of peroxidase is to oxidize molecule at the expense of H2O2. The activity of guaiacol dependent POD increased during entire ontogeny of bean cotyledons (Wilhelmova 1998).The increase in POD activity has also been reported in the senescing cotyledons of cucumber (Kanazawa et al. 2000) and attached nodal leaves of Cajanus cajan L. during development and senescence (Jakhar and Mukherjee 2006).

Protein breakdown has been also considered to be one of the important events during leaf senescence and enzymes associated with the process are known as proteases. Data incorporated in Fig. 3 have shown degradation of protein content and gradual increment in protease activity with the advancement in senescence. Protein content at initial day was 20.934 mg/100 mg on dry weight basis. As number of days increased and senescence process progressed further, per cent degradation of protein changed to 49.62, 55.68 and 83.59 at 2, 4 and 6-day. Among applied plant growth substances, KN was found to be quite effective in retaining proteins in comparison to control; the higher concentration of KN could give the best results (Fig. 3). However, no appreciable change could be seen after MOR treatments. Kuraishi (1968) have shown that the higher protein content in ageing leaves after KN treatment was due to a delay in protein breakdown and not due to increased synthesis. The effect of KN in retarding protein degradation confirmed findings of earlier workers (Paranjothy and Wareing 1971; Martin and Thimann 1972a, b). Studies carried out earlier indicate that morphactins can also bring down chlorophyll and protein hydrolysis (Schneider 1970; Mukherjee et al. 1983).

Hydrolysis of proteins to free amino acids depends on the action of several endopeptidases and exopeptidases (Hortensteiner and Feller 2002; Otegui et al. 2005). Several other proteases, such as, endoproteases, amino and carboxypeptidase are abundant in senescing tissues. Also, many cysteine, aspartic and metallo-proteases have been identified among the senescence upregulated genes (Browse and Somerville 1991). It may be assumed that higher proteolytic activity may be the prime reason for the protein degradation as has been observed in earlier studies (Kumar and Mukherjee 1992; Mukherjee and Rao 1993; Jakhar and Mukherjee 2006). Present findings also indicate that protein loss is connected with the increment in protease activity. The activity of protease was particularly higher in the advanced stages of senescence. Here not only KN but MOR could also reduce the enzymatic activity. Best result in controlling protease activity was obtained with higher concentration of KN followed by lower KN, higher MOR and lower MOR concentration (Fig. 3). It is possible to check the degradation of protein, DNA and RNA by KN application in senescing leaves, flowers and pods of Cajanus cajan L. (Mukherjee and Kumar 2007). Earlier investigation on leaf disc senescence in Spinacia oleracea L. has revealed the effectiveness of KN in minimizing protease activity (Mukherjee and Jakhar 2009). A comparative study on senescence regulation by KN and MOR using leaf discs of Lycopersicon esculentum and Solanum melongena has revealed that both PGRs are highly active to modify the retention of chlorophylls and protein degradation (Rajbala and Mukherjee 2004). They also bring down protease activity significantly but KN has been more effective than MOR. Evidence is available that some enhanced proteases accumulate in the vacuole as an inactive aggregate which slowly mature to produce a soluble active enzyme at later stage of senescence (Yamada et al. 2001) but there are proteases also in chloroplasts as well as in peroxisomes (Hellgren and Sandelius 2001).

Present investigation also revealed an increment in reducing and non reducing sugars. Increment in non reducing sugars was constantly higher than reducing sugars. Per cent increments of reducing and non reducing sugars in control after 6-day was 959.03 and 1173.45 respectively. Total sugar increment was maximum between 4 and 6-day. Kinetin and morphactin applications appreciably brought down the accumulation of both sugars which is very interesting as seen in 6-day samples. Balibrea et al. (2004) have provided a mechanistic explanation for the interactions between cytokinins and sugars in the regulation of senescence. By inducing extracellular invertase cytokinin increases sugar utilization, thereby surprisingly decreasing glucose accumulation and delaying senescence. It was postulated that due to reduction in photosynthetic efficiency, there may be sugar starvation which may act as a signal for induction of senescence (Hensel et al. 1993). However, later studies revealed that the accumulation of glucose and sucrose repress the transcription of the photosynthetic genes (Rolland et al. 2002). Moreover, senescing leaves have been found to accumulate glucose and fructose rather than exhibiting sugar starvation (Wingler et al. 1998; Stessman et al. 2002). Similarly, Quirino et al. (2001) and Stessman et al. (2002) have reported hexose accumulation in senescing Arabidopsis. Present findings on sugar accumulation with progress of senescence in radish leaf discs in light further confirm the above observation. Sugar signaling has emerged as an important regulator of leaf senescence (Rolland et al. 2002). Glucose levels in cells are continuously assessed by hexose kinase (HXKs), whilst some glucose signaling also occurs through a hexose kinase-independent pathway. A complex interaction has been found between glucose signaling and signal transduction through various hormones such as ABA, auxin, cytokinin and ethylene. For example HXK1 is present in high molecular-weight complexes in the nucleus, where it controls transcription and the proteasome mediated degradation of the ethylene insensitive3 (EIN3) transcription factor, thereby counteracts the effect of ethylene (Rolland et al. 2006). Furthermore, sugars can prevent the up regulation of EIN3 transcription factors during senescence (Van Hoeberichts et al. 2007), which might also act through HXK. These data indicate that it is plausible to assume that sugars might have a role in signaling at least some of the changes in overall plant status that leads to leaf senescence.

Conclusion

From overall discussion it can be concluded that to some extent two concentrations of KN (0.375 μM and 3.75 μM) and MOR (3.64 μM and 36.4 μM) used in this investigation were effective in checking the ongoing senescence process in leaf discs. But higher concentration of kinetin exhibited a significant retention in the levels of chloroplast pigments and proteins in all stages in comparison to respective controls. This concentration of kinetin was able to reduce both peroxidase and protease activity, and the amount of total soluble sugars significantly in all stages.

Future plan of action

Vegetables harvested before full maturity are exposed to enormous stress by the sudden interruption of the energy and nutrient supply. Green leafy vegetables show a very fast post-harvest senescence during storage resulting loss of chlorophyll, damage to cellular structures and finally cell death. Being a cruciferous vegetable, R. sativus is an important source of dietary nutrients and antioxidants. However, the available information is inadequate on variability of SOD, POD, APX and CAT activity in detached as well as attached systems. This knowledge will have greater impact to understand the shelf life of produce. Further investigation can be carried out to find out the stage of the leaves having best antioxidant system in various green leafy vegetables and to correlate them with changes at molecular level. Therefore such a study on leaf senescence will not only contribute to our knowledge about this fundamental developmental process, but it may also lead to manipulating senescence for improving crop productivity.

Acknowledgement

Financial assistance received from University Grants Commission, New Delhi to the first author is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- PGRs

Plant growth regulators

- PFD

Photon flux density

- POD

Peroxidase

- KN

Kinetin

- MOR

Morphactin (Chlorflurenol methyl ester-CME-74050)

- SA

Salicylic acid

- CaCO3

Calcium carbonate

- HXKs,HXK1

Hexose kinase

- EIN3

Ethylene insensitive3

- ipt

Isopentenyl transferase

- SAG12

Senescence associated gene12

References

- Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts: polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteca RN (1996) Plant growth substances: principles and applications. Springer, pp 332

- Balibrea Lara M, Gonzalez Garcia M, Fatima T, Ehneß R, Kyun Lee T, Proels R, Tanner W, Roitsch T. Extracellular invertase is an essential component of cytokinin-mediated delay of senescence. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1276–1287. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. To estimate protein utilizing the principles of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J, Somerville CR. Glycerolipid synthesis: biochemistry and regulation. Ann Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:467–506. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.42.060191.002343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CJ, Kao CH. H2O2 metabolism during senescence of rice leaves: changes in enzyme activities in light and darkness. Plant Growth Regul. 1998;25:11–15. doi: 10.1023/A:1005903403926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyad’s II. Ontogenetic changes in the photosynthetic apparatus and effects of cytokinins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;36:527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Costa ML, Civello PM, Chaves AR, Martinez GA. Effect of ethephon and 6-benzylaminopurine on chlorophyll degradaing enzyme and a peroxidase –linked chlorophyll bleaching during post harvest senescence of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L.) at 20 degrees C. Postharvest Biol Tech. 2005;35:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2004.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S, Amasino RM. Inhibition of leaf senescence by auto regulated production of cytokinin. Science. 1995;70:1986–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan S, Amasino RM. Making sense of senescence. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:313–319. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover A, Mohanty P. Leaf senescence-induced alteration in structure and function of higher plant chloroplasts. In: Abrol YP, Mohanty P, Govindjee, editors. Photosynthesis: photoreaction to plant productivity. London: Kluwer; 1993. pp. 225–255. [Google Scholar]

- Hart FL, Fisher HJ. Modern food analysis. New york: Springer; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hensel LL, Grbic Baumgarten DA, Bleecker AB. Developmental and age related processes that influence the longevity and senescence of photosynthetic tissues in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1993;5:553–564. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.5.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellgren LI, Sandelius AS. Age dependent variation in membrane lipid synthesis in leaves of garden pea (Pisum sativum) J Exp Bot. 2001;365:2275–2282. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.365.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidema J, Makino A, Kurita Y, Mae T, Ojima K. Changes in the levels of chlorophyll and light harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein of PS II in rice leaves aged under different irradiance from full expansion through senescence. Plant Cell Physiol. 1992;33:1209–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges DM, Forney CF. The effect of ethylene, depressed oxygen and elevated carbon dioxide on antioxidant profile of senescing spinach leaves. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:645–655. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.344.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoeberichts FA, Doorn WG, Vorst O, van Hall RD, Wordragen MF. Sucrose prevents up-regulation of sensececent-associated genes in carnation petals. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:2873–2885. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden M. Chlorophylls. In: Goodwin TW, editor. Chemistry and biochemistry of plant pigments. London: Academic; 1965. pp. 462–488. [Google Scholar]

- Hortensteiner S, Feller U. Nitrogen metabolism and remobilization during senescence. J Exp Bot. 2002;53:927–937. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.370.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakhar S, Mukherjee D. Chloroplast pigments, free and bound amino acids, activities of protease and peroxidase during development and senescence of attached nodal leaves of Cajanus cajan L. J Plant Biol. 2006;33:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa S, Sano S, Koshiba T, Ushimaru T. Changes in antioxidative enzymes in cucumber cotyledons during dark-induced senescence. Physiol Plant. 2000;109:211–216. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2000.100214.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kar M, Streh P, Hertwig B, Feierabend J. Sensitivity to photo damage increases during senescence in excised leaves. J Plant Physiol. 1993;141:538–544. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R (1990) Senescence regulation in pigeon pea with reference to water stress and growth substances. Ph.D. Thesis. Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra

- Kumar R, Mukherjee D. Effect of kinetin on growth and yield of pigeonpea. Geobios. 1992;19:204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kuraishi S. The effect of kinetin on protein level of Brassica leaf discs. Physiologia Plant. 1968;21:78. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1968.tb07232.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Zhang J. Changes in photosystem II function during senescence of wheat leaves. Physiol Plant. 1998;104:239–247. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1998.1040212.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Zhang J. Modifications in photosystems II photochemistry in senescent leaves of maize plants. J Exp Bot. 1998;49:1671–1679. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/49.327.1671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maehly AC. Determination of peroxidase activity. In: Glick D, editor. Methods of biochemical analysis. New York: Interscience Publications, Inc; 1954. pp. 385–386. [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Thimann KV. The role of protein synthesis in the senescence of leaves I. The formation of proteases. Plant Physiol. 1972;49:64–71. doi: 10.1104/pp.49.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Thimann KV. The role of protein synthesis in the senescence of leaves II. The influence of amino acids on senescence. Plant Physiol. 1972;50:432–437. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.4.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matile P, Hortensteiner S, Thomas H, Krautler B. Chlorophyll breakdown in senescent leaves. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1403–1409. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.4.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MS, Garratt LC, Schepers F, Jordi WJRM, Stoopen GM, van Davelaar E, Rhijk JHA, Power B, Davey MR. Effects of PSAG 12-IPT gene expression on development and senescence in transgenic lettuce. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:505–516. doi: 10.1104/pp.010244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie MJ, Mett V, Reynolds PHS, Jameson PE. Controlled cytokinin production in transgenic tobacco using a copper inducible promoter. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:969–977. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D, Jakhar S. Combined application of serine and kinetin regulates leaf disc senescence in Spinacia oleracea L. Indian J of Plant Physiol. 2009;14:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D, Kumar R. Kinetin regulates plant growth and biochemical changes during maturation and senescence of leaves, flowers and pods of Cajanus cajan L. Biol Plant. 2007;51:80–85. doi: 10.1007/s10535-007-0016-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D, Rao KUM. Protease activity in leaves, flowers and pods of Cajanus cajan during maturation and senescence. J Plant Physiol Biochem. 1993;20:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D, Jain VK, Gupta VK. Moprhogenetic and biochemical changes in Lycopersicon esculentum after the treatment with a morphactin. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1983;10:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Nooden BD, Nooden SM. Effect of morphactin and other auxin transport inhibitors on soybean senescence and pod development. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:263–266. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otegui MS, Noh Y-S, Martinez DE, Villa Petroff MG, Staehelin LA, Amasino RM, Guiamet JJ. Senescence-associated vacuoles with intense proteolytic activity develop in leaves of Arabidopsis and soybean. Plant. 2005;41:836–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjothy K, Wareing PF. The effect of abscisic acid, kinetin, and 5-fluorouracil on ribonucleic acid and protein synthesis in senescing leaf discs. Planta. 1971;99:112–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00388243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponmeni G, Mukherjee D. Kinetin induced alteration in senescence of red gram leaves. Indian J Plant Physiol (New Series) 1997;2:250–251. [Google Scholar]

- Quirino BF, Reiter WD, Amasino RM. One of the two tandem Arabidopsis genes homologous to monosaccharides transporters is senescence associated. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;46:447–457. doi: 10.1023/A:1010639015959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajbala, Mukherjee D. Senescence regulation in leaf discs of Lycopersicon esculentum and Solanum melongena by kinetin and a morphactin in dark. Eco-Research J Bio-Sciences. 2004;31:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rao KUM (1990) Senescence of leaves and reproductive parts of Cajanus cajan L. Ph.D. Thesis, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra

- Rao KUM, Mukherjee D. Some metabolic changes during development and senescence in the leaves of Cajanus cajan L. J Indian Bot Soc. 1990;69:311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Reimerdes EH, Klostermeyer H. Determination of proteolytic activity on caesin substrates. Methods Enzymol. 1976;45:26–28. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(76)45005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson PRH, Donnison IS, Wang K, Frame B, Pegg SE, Thomas A, Thomas H. Leaf senescence is delayed in maize expressing the Agrobacterium ipt gene under the control of a novel, maize senescence enhanced promoter. Plant Biotechnol J. 2004;2:101–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-7652.2004.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F, Moore B, Sheen J. Sugar sensing and signaling in plants. Plant Cell Suppl. 2002;5:S185–S205. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider G. Morphactins: physiology and performance. Ann Rev Plant Physiol. 1970;21:499–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.21.060170.002435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F, Baena-Gonzalez E, Sheen J. Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: conserved and novel mechanisms. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:675–709. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart CM. Gene expression during leaf senescence. New Phytol. 1994;126:419–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stessman D, Miller A, Spalding M, Rodermel S. Regulation of photosynthesis during Arabidopsis leaf development in continuous light. Photosynth Res. 2002;72:27–37. doi: 10.1023/A:1016043003839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmova N. The role of oxidative damage in cotyledon ageing. Abstracts J Expt Bot. 1998;321:49. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wingler A, Schawen A, Leegood RC, Lea PJ, Quick W. Regulation of leaf senescence by cytokinin, sugars and light. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:329–335. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.1.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Matsushima R, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. A slow maturation of a cysteine protease with a granulin domain in the vacuoles of senescing Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1626–1634. doi: 10.1104/pp.010551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yemm EW, Cocking EC. The determination of amino acids with ninhydrin. Analyst. 1955;80:209–213. doi: 10.1039/an9558000209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]