Abstract

Two swine influenza (SI) H1N1 virus was isolated from a pig during a severe outbreak of respiratory disease in south China. The two H1N1 influenza viruses were classical SI virus. A/swine/Guangdong/L6/09 is classical SI virus of recent years, which is of the main SI virus in China. Howere, A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09 was closet to A/swine/Iowa/1931, which was the first isolated SI virus and had demonstrated significant pathogenicity in animal models. The results of phylogenetic analysis of A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09 showed a close relationship with the 1918 pandemic virus. The results suggested that the previous SI virus appeared again. Whether, it brought a new pandemic to pigs deserves more attention.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13337-011-0035-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Swine influenza virus H1N1, Phylogenetic analysis

Since April 2009, the H1N1 influenza virus caused a global pandemic which got people in great trouble. The virus was originated from Mexico and then USA. As of 29 November 2009, worldwide more than 207 countries and overseas territories or communities have reported laboratory confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1 2009, including at least 8,768 deaths (http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_12_04/en/index.html). It was reported that the novel H1N1 influenza virus is an uncommon reassortant virus [10]. That the swine was considered as “mixer” between human influenza and avian influenza is verified [2, 7, 16]. This pandemic confirm again that the swine influenza (SI) have the ability of cross-species transmission from pigs to human, and then from human to human. Once the influenza virus obtains others virus’ gene segments and a novel influenza virus will show up, in the train of the pandemic. It is clear that SI plays a significant part in the public health.

Influenza A virus can infect many animal hosts including human, pigs, birds, horse, dogs and so on. However the influenza virus has a high specificity for hosts-species barrier. Under the pressure of vaccine and antiviral agents, the influenza virus has to make mutation in two major forms: antigenic drift and antigenic shift. So far three major different SIV subtypes, H1N1, H3N2 and H1N2, have been circulated worldwide in pig flocks [1]. In the past three outbreaks of influenza including Spanish Influenza in 1918, Asian influenza in 1957, Hong Kong Influenza in 1968, all these pandemics have been linked to SI virus. So it is necessary to understand the information of SIV. It will help us to master the trend of influenza virus mutates and make some effective measures to control the epidemic.

In this present study, two strains of SI virus were isolated from breathing difficulties in young pigs. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the H1N1 (A/swine/Guangdong/L6/09) shows that all of eight segments including hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), matrix (M), nucleoprotein (NP), non-structural (NS), PA, PB1 and PB2, were swine origin. The H1N1 (A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09) SI displayed that it was close to classical SI viruses first isolated in 1930s which were direct descendants of the 1918 pandemic virus [14].

The two H1N1 SI viruses were isolated from dyspneic swine herd of Guangdong in March 2009. Initial isolations of the viruses were performed in 10-day-old specific pathogen free (SPF) embryonated chicken eggs through the allantoic route, incubated at 35°C for 72 h. Embryonic death was monitored every 12 h, and then Allantoic fluid were harvested under aseptic conditions and stored at −70°C for reserved. Subtype identification of the viruses were determined by standard hemagglutination inhibition and NA inhibition assays using specific antisera to the reference strains of influenza viruses confirmed through RT-PCR with a set of subtype-specific primers. The two influenza viruses were named: A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09(H1N1) and A/swine/Guangdong/L6/09(H1N1).

The virus RNA was extracted from allantoic fluid by using TRIzol reagents (invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed as a one-step reaction with the TAKARA OneStep RT-PCR Kit, according to manufacturer’s protocol [8]. The primer of reverse transcription use 12 bp (5-AGC AAA AGC AGG-3). cDNAs were synthesized at 37°C for 1 h using M-MLV reverse-transcription system (Promega). Full-length PCR amplification of eight RNA segments was performed with a set of primer.

The RT-PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis in agarose gel, and specific DNA was excised and purified with the ColumnMate Gel Extraction UF Kit (Watson Biotechnologies, Inc).The sequences of eight RNA segments were sequenced at BIOSUNE. Analysis of nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were aligned and edited by means of the profile-based progressive alignment procedure, ClustalW, using the DNASTAR and BioEdit Package, Version 7.0 software.

Phylogenetic analysis was carried out by analyzing the data obtained here with those of other sequences of influenza viruses from GenBank database. A neighbor-joining nucleic acid tree was constructed in MEGA 4.0 using the Kimura 2-parameter model with 1,000 bootstrap replicates as previously described [13], and multiple sequence alignments were conducted with the Clustal W application. In this study, the nucleotide sequences used for the phylogenetic analysis are as follows: PB2 (nt 1377–2307), PB1 (nt 1328–2297), PA (nt 1256–2150), HA (nt 65–1689), NP (nt 45–1563), NA (nt 35–1422), M (nt 25–996), NS (nt 41–852). Nucleotide sequences from the A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09 (H1N1) isolate have been submitted to GenBank with accession numbers HQ877024–HQ877031. Nucleotide sequences from the A/swine/Guangdong/L6/09 (H1N1) isolate have been submitted to GenBank with accession numbers HQ880611–HQ880618.

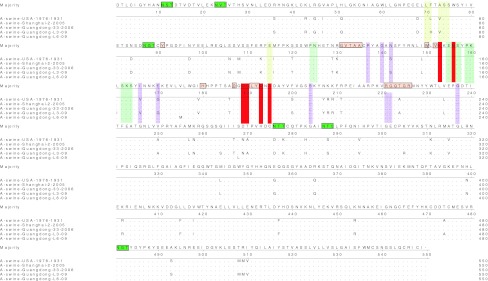

The HA deduced amino acid sequences of the two H1N1 viruses was analyzed in this study. A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09 has five potential glycosylation sites in HA, including four in HA1 and one in HA2. A/swine/Guangdong/L6/09 has six potential glycosylation sites in HA, including five in HA1 and one in HA2. Most of receptor binding sites of the two viruses are shown to be highly conserved. The two H1N1 viruses have one mutation in 224(A&T). Four of antigen site are a more conservative region compared to others. There is the same cleavage site (PSIQSRGF) in the two viruses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Molecular of the HA gene of the two H1N1 SI viruses and reference strains. Green horizontal box is potential glycosylation sites; undertint horizontal box is receptor binding sites; antigen site Sa is reseda shadow, Sb is red shadow, Ca is pink shadow, Cb is yellow shadow

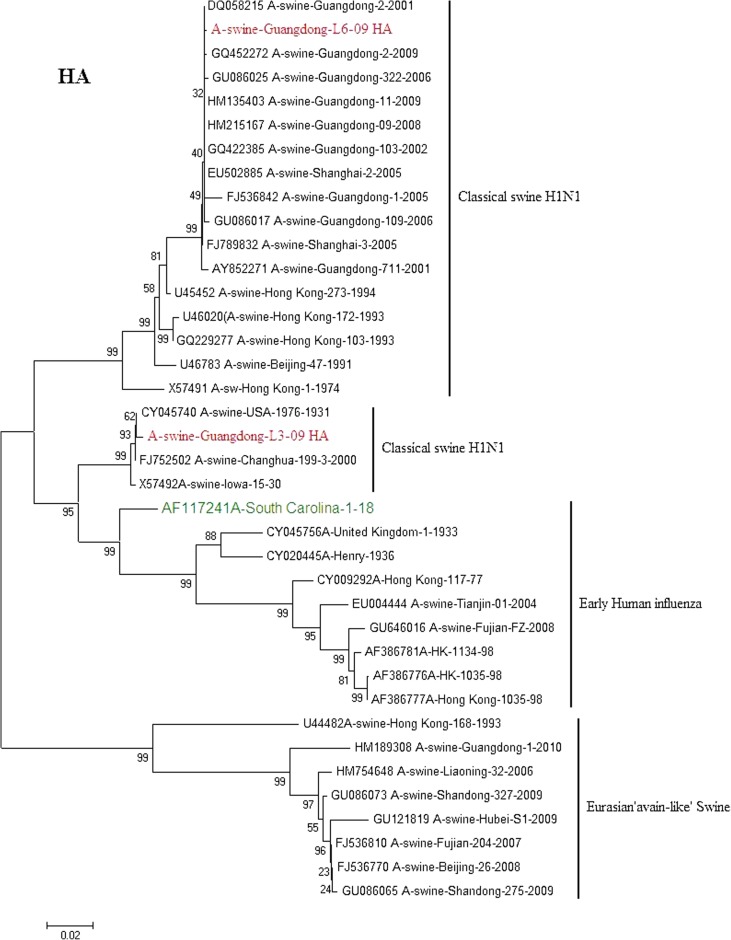

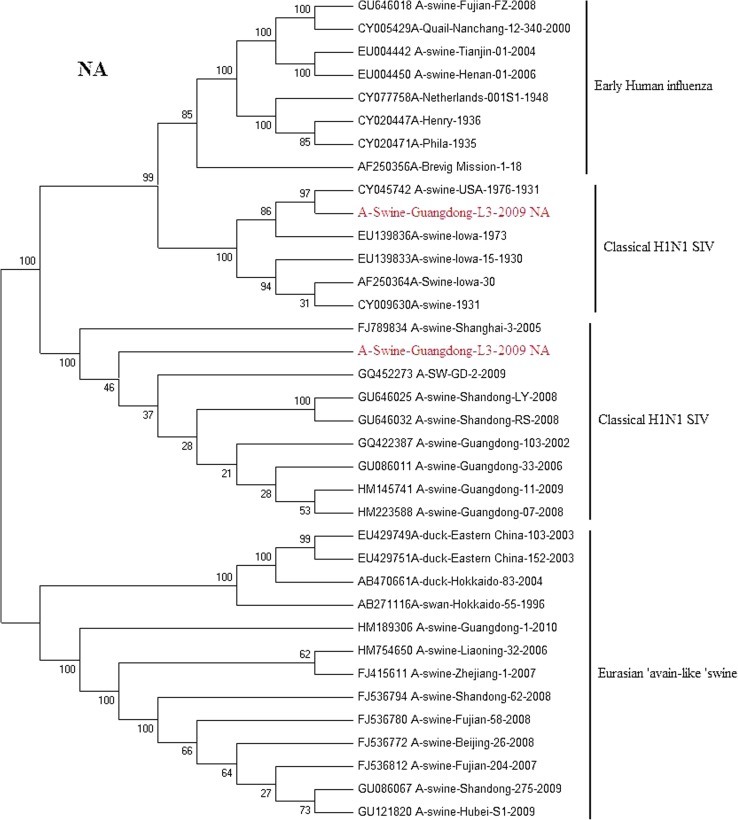

Phylogenetic trees of HA and NA gene of A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09(H1N1) and A/swine/Guangdong/L6/09(H1N1) isolate genes are shown in (Figs. 2, 3). All eight genes of A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09(H1N1) were closed to A/swine/Iowa/1931, which is the first isolated SI virus. The result shows that the virus may come from early human influenza virus. While A/swine/Guangdong/L6/09(H1N1) is originated from classical swine H1N1 influenza virus. All SIV H1N1 from China are provided here. In the final analysis, the SIV H1N1 of China was separated into three lineages: classical SI, human-like and European avian-like SI. The major SIV H1N1 from across china belongs to cH1N1 and European avian-like SI, and a few is phylogenetically close to human lineage. SIV H1N1 has already caused an epidemic in swine herd of China.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of the HA gene of A/swine/Guangdong/L3/2009 and A/swine/Guangdong/L6/2009 compared to genetically related influenza viruses. Horizontal distances are proportional to the minimum number of nucleotide differences required to join nodes and sequences. Vertical distances are for spacing branches and labels. The phylogenetic trees were generated by using the neighbor-joining algorithm. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships of the NA gene of A/swine/Guangdong/L3/2009 and A/swine/Guangdong/L6/2009 compared to genetically related influenza viruses. Horizontal distances are proportional to the minimum number of nucleotide differences required to join nodes and sequences. Vertical distances are for spacing branches and labels. The phylogenetic trees were generated by using the neighbor-joining algorithm. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) is shown next to the branches

In order to detect the prevalence of such H1N1 in swine population, among these sick pigs, a total number of 475 swine serum samples were collected from 11 farms at Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan Provinces, China. These sera were tested against H1 subtype by using hemagglutination inhibition assay, and our results demonstrated that 101 of these samples (21.4%) were positive against H1 SIV.

Influenza virus infection is an important cause of respiratory disease among pigs throughout the swine-producing regions of the world. The Classical swine H1N1 influenza was first reported in 1991 in Beijing [6]. Then Classical swine H1N1 influenza were isolated from Guangdong, Hunan, Jiangxi, Henan, Guizhou and Hong Kong from 1993 to 1994 [5]. From now on Classical H1N1 SI begins to spread in China. A number of SIV were isolated from 2002 to 2010. Classical H1N1 SI virus infections typically present with clinical signs including fever, anorexia, weight loss, lethargy, nasal and ocular discharge, coughing and dyspnea. It causes a great loss in the pig-breeding industry [4]. The European avian-like SI was show up in Hong Kong in 1996 [5]. From the phylogenetic analysis, A/Sw/HK/168/93 is a representative of avian-like SI in China. European avian-like SI caused market panics in Hong Kong in recent years [12]. The A/swine/Guangdong/L3/09(H1N1) is still emerging in Guangdong pigs. After 70 years the virus has highly conserve. The exact origin of A/swine/Iowa/1931 is still unknown; but it is considered to relate to early human influenza. What effect will the virus bring to pigs? It needs further tracking monitoring.

Southern China is designated as a putative influenza epicenter [11]. Both 1957 and 1968 pandemic influenza emerged from this area. The precursor of currently is still ongoing. 1997 H5N1 HPAIVs were identified also in Guangdong in Southern China [3, 15]. Since then, various genotypes of these H5N1 viruses have been identified in this area. Since 2007, avian origin H3N2 canine influenza viruses have been identified also in 100 the dogs in Southern China [9]. This two SIV is not isolated from the same farm. But those pigs show same clinical symptoms, including dyspnea and runny nose. After a time some pigs have porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) in two farms. What does SI have any connection with PRRS in pigs? In the next work some related research will be done. In addition swine flu has been playing a very important role in public health. It is helpful to master flu variation information by monitoring in this area.

Electronic supplementary material

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: PB2 (JPEG 199 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: PB1 (JPEG 233 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: PA (JPEG 218 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: NP (JPEG 220 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: MP (JPEG 241 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: NS (JPEG 246 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Basic Research Program (973 Project) from China Ministry of Science and Technology (grant number 2011CB504703-1) and International Cooperative Projects (grant number S2011ZR0429) and China Guangdong hundred thousand engineering.

Footnotes

Wei-li Kong, Yu-mao Huang are the authors contributed equally.

References

- 1.Brown IH. The epidemiology and evolution of influenza viruses in pigs. Vet Microbiol. 2000;74(1–2):29–46. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castrucci MR, Donatelli I, Sidoli L, Barigazzi G, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG. Genetic reassortment between avian and human influenza A viruses in Italian pigs. Virology. 1993;193:503–506. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan PK. Outbreak of avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in Hong Kong in 1997. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(2):S58–S64. doi: 10.1086/338820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Easterday BC, Hinshaw VS. Swine influenza. In: Leman AD, Straw BE, Mengeling WL, D’Allaire SD, Taylor DJ Jr, editors. Disease of swine. Ames: Iowa State Press; 1992. pp. 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan Y, Shortridge KF, Krauss S, Li PH, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG. Emergence of avian H1N1 influenza viruses in pigs in China. J Virol. 1996;70(11):8041–8046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8041-8046.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo Y, Webster RG. Swine influenza virus (H1N1) of discovery and its origin investigation. Chin J Exp Clin Virol. 1992;6(4):347–353. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito T, Couceiro JN, Kelm S, Baum LG, Krauss S, Castrucci MR, Donatelli I, Kida H, Paulson JC, Webster RG. Molecular basis for the generation in pigs of influenza A viruses with pandemic potential. J Virol. 1998;72:7367–7373. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7367-7373.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar P, Kumar B, Gupta A, Sharma B, Vijayan VK, Khare S, Singh V, Daga MK, Chadha MS, Mishra AC, Kaur H, Khanna M. Diagnosis of novel pandemic influenza virus 2009 H1N1 in hospitalized patients. Indian J Virol. 2010. doi:10.1007/s13337-010-0005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Li S, Shi Z, Jiao P, Zhang G, Zhong Z, Tian W, et al. Avian-origin H3N2 canine influenza A viruses in Southern China. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10(8):1286–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Shortridge KF, Stuart-Harris CH. An influenza epicentre? Lancet. 1982;2(8302):812–813. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith GJD, Vijaykrishna D, Bah J, et al. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature. 2009;459:1122–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature08182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(1):15–22. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan X-F Isolation and characterization of avian influenza viruses in China. Master Thesis, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou; 1998.

- 16.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:152–179. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.152-179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: PB2 (JPEG 199 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: PB1 (JPEG 233 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: PA (JPEG 218 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: NP (JPEG 220 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: MP (JPEG 241 kb)

Phylogenetic trees for two SI viruses isolated from southern China: NS (JPEG 246 kb)