Abstract

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) is one of the most important viral pathogen infecting several plant species in India. Five isolates of CMV obtained from cucumber, muskmelon, tobacco and tomato from distinct geographical locations in India were analysed based on host-reactions and genome sequence. The majority of the isolates were very similar and only two isolates, Tfr-In and Tss-In showed distinct symptoms in tomato and high sequence diversity (77.8%) in coat protein (CP) gene. Tfr-In was isolated from tomato fruit showing grey patches in Aurangabad and Tss-In from tomato plant showing shoe-string symptoms in New Delhi. The RNA-3 genomes of Tfr-In (2,214 nt; JF279606), shared only 70.3% nucleotide sequence identity with Tss-In (2,178 nt; JF279605. The complete RNA-3 genome of Tss-In and Tfr-In were compared with that of 65 CMV isolates reported from various plants of the world, which formed four distinct subclades-IA, -IB, -IC and -II. The Tfr-In isolate clustered with the CMV subgroup-IB and Tss-In with the subgroup-II. The comparison of the RNA-3 sequence of both the isolates revealed maximum heterogeneity in the intergenic region (IR). Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) based detection of CMV subgroup-I and -II was developed designing primers from flanking IR region. The specificity of the RT-PCR detection was confirmed using Tfr-In and Tss-In representing subgroup-I and -II and validated with field samples of tomato, cucurbits and chilli. This is the first report of complete RNA-3 of subgroup-IB CMV causing grey patches in tomato fruit and subgroup-II CMV causing shoe-string symptoms in tomato in India. The present and previous studies together showed that tomato in India was affected by multiple strains of CMV.

Keywords: Cucumber mosaic virus, Tomato, CMV subgroups, Shoe-string, Grey-patch, RT-PCR, RNA-3 genome

Introduction

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) is a single-stranded positive sense RNA plant virus belonging to the genus Cucumovirus of family Bromoviridae. It is distributed worldwide and has a very broad host range [20] of about 1,200 species causing severe damage in some of the most economically important species under Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae families. CMV has tripartite genome consisting of three RNAs (RNA-1, RNA-2 and RNA-3), RNA-1 and RNA-2 encodes protein required for replication of the virus [6, 13]. RNA-3 contains two genes, 3a encoding cell to cell movement protein (MP) and 3b encoding coat protein (CP) [21]. Numerous isolates/strains of CMV have been reported from several countries. CMV isolates are grouped into two main subgroups-I and -II based on their biological, serological and molecular properties [13]. Based on the diversity of CP gene and 5′ untranslated (UTR) sequence, subgroup-I has been further divided into two groups, IA and IB [12, 20]. Subgroups-IA and -IB shares a close sequence relationship of 92–95% identity, while subgroups-II are quite distantly related to subgroup-I with only 75% sequence identity [19].

In India, CMV is an economically important and widely occurring plant virus and has been reported from many different host plants such as cucumber [4], black pepper [5], Amaranthus, Datura [28], Rauvolfia serpentine, Jatropha curcas [16, 17], Egyptian henbane [23], gladiolus [15], tomato [29], geranium [32], banana [1]. Tomato, an important vegetable crop is cultivated throughout India. CMV is one of the important viral pathogen of tomato where it induces various symptoms—necrosis, mottling, mosaic, narrowing or shoe-string of leaves and stunting of plants [9, 14, 33]. The molecular diversity among CMV isolates in India and elsewhere have been studied mainly based on CP gene sequence. However, the recent database showed availability of 65 full-length RNA-3 sequences of CMV isolates from different countries including 10 from India.

In the present study, five isolates of CMV from different crops in distant geographical locations in India were studied based on host reactions and sequence diversities in CP gene. Two tomato isolates with distinct symptom phenotypes and high sequence diversity in CP gene were identified and complete RNA-3 genome sequence was generated. Phylogenetic relationships of these two isolates with the other CMV isolates occurring worldwide was established. The comparison of complete RNA-3 of the two isolates showed distinct sequence heterogeneity at the end of MP and beginning of CP open reading frame (ORF), which were utilised to develop reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) based detection of CMV subgroup-I and -II.

Materials and Methods

Virus Isolates and Transmission

CMV isolates were collected from different hosts and places in India (Table 1). Presence of CMV in these samples was confirmed by transmission electron microscope and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using polyclonal antibody to CMV. All the isolates were mechanically inoculated to cucumber, Nicotiana glutinosa and tomato cv. Pusa Ruby using 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 containing 0.15% sodium sulphite under greenhouse conditions. Symptoms were recorded 5 weeks post inoculation. Transmission was confirmed by RT-PCR using CP based primers, BM05F and BM06R (Table 2).

Table 1.

Isolates of CMV used in the study

| S. no. | Isolate | Sample | Place | Collection year | Field symptom | Symptoms under greenhouse conditionsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato | Cucumber | N. glutinosa | ||||||

| 1 | Tfr-In | Tomato fruit | Aurangabad | 2005 | Grey patches on tomato fruit | cs | m | mb |

| 2 | Ban-In | Tobacco leaf | Bangalore | 2007 | Mottling | mt | m | mb |

| 3 | Pun-In | Cucumber leaf | Pune | 2007 | Mosaic | mt | mt | mb |

| 4 | Bal-In | Muskmelon leaf | Ballabgarh | 2008 | Mottling | cs | mt | mb |

| 5 | Tss-In | Tomato leaf | New Delhi | 2008 | Shoe-string | mt, ss | – | mb |

aSymptoms developed following sap inoculation (mb mosaic blistering, m mosaic, mt mottling, ss shoe-string, cs chlorotic spots

Table 2.

Primers used for the amplification of CMV isolates

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Expected product (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | Used for amplification of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM05F | AGTCGAGTCATGGACAAATC | 660 | 45 | CP |

| BM06R | TTAGACTGGGAGCACCC | Subgroup-I and -II | ||

| BM35F | GTAATCTTACCACTGTGTGT | 960 | 52 | 5′ UTR + MP |

| BM38R | CTAAAGACCGTTAACCACC | |||

| BM05F | AGTCGAGTCATGGACAAATC | 980 | 50 | CP + 3′ UTR |

| BM36R | TGGTCTCCTTTTGGAGACC | |||

| BM51F | AACAATAGCTTCAGATCGCA | 376 | 54 | IR |

| BM52R | ACTAGCATTGGGAGATCCA | Subgroup-II | ||

| BM53F | CCGAAACCTTTAGTCCGC | 386 | 54 | IR |

| BM54R | CCGGCACTGGTTGATTCA | Subgroup-I |

RNA Extraction

The double stranded RNA (dsRNA) was isolated with slight modifications of the method described by Dodds et al. [7]. Briefly, about 0.2 g of leaf tissue was ground with liquid nitrogen and RNA was isolated using phenol, chloroform–isoamyl alcohol and CF-11. The dsRNA bound to CF-11 was released in 1X STE and isolated by alcohol precipitation. Finally, the dsRNA was dissolved in 25 μl of RNase free distilled water and stored at −80°C.

RT-PCR and Cloning of RNA-3

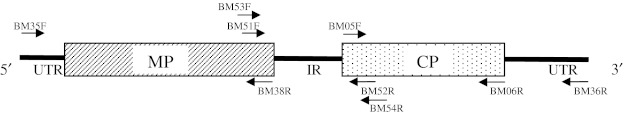

RT-PCR for all the isolates was carried out by using CP gene specific primers of CMV, BM05F and BM06R (Table 2) and the amplified fragments were cloned in pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega Madison, WI, USA) and sequenced. Two distinct isolates, Tss-In and Tfr-In showing considerable sequence diversity in CP gene were selected for cloning of complete RNA-3 genome. The complete RNA-3 genome was cloned in three segments: the 5′ segment containing 5′-UTR and MP ORF and 3′ segment containing 3′-UTR and CP ORF were amplified with the primers, BM35F & BM38R and BM05F & BM36R (Table 2; Fig. 1), respectively, designed based on the comparison of the sequences of CMV isolates available in the database. The remaining intergenic region (IR) between 5′ and 3′ fragments was amplified with the primers BM51F and BM52R for Tss-In isolate and BM53F and BM54R for Tfr-In isolate, which were obtained from the specific sequence of 5′ and 3′ segments (Table 2; Fig. 1). Genome amplification was carried out by two steps RT-PCR using RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kits (MBI Fermentas, USA) and Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, USA), in a Biometra T Personal thermocycler with the following temperature cycle: cDNA synthesis at 37°C for 1 h, followed by PCR: one cycle at 94°C for 2 min, 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 45–54°C (Table 2) for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The RT-PCR amplicons were purified by using Wizard SV gel and PCR clean up Kit (Promega Madison, WI, USA) and ligated into a linear pGEM T-Easy vector by using T4 DNA ligase (Promega Madison, WI, USA). Cells of E. coli strain JM109 were transformed with the ligation products [24] and the recombinant clones were identified by PCR and restriction digestion and sequenced in ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer at Chromous Biotech Pvt Ltd, Bangalore.

Fig. 1.

RNA-3 genome of CMV showing locations of primers used for amplification. MP movement protein ORF, CP coat protein ORF, UTR untranslated region. Arrows indicate location of primers listed in Table 2

Sequence Analysis

The complete sequences of RNA-3 genome for both the isolates were Tfr-In and Tss-In assembled by aligning on overlapping regions using BioEdit software (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/BioEdit.html). The RNA-3 of Tfr-In and Tss-In isolates were compared with that of 65 isolates of CMV retrieved from the GenBank [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/index.html]. The sequence data, accession, strain/isolate, country of origin, and year of collection were presented in the Table 3. Multiple alignment and sequence identity matrix of the sequences were performed using ClustalW programme. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted in MEGA4 with Peanut stunt virus (PSV) as outgroup [31]. The evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum parsimony (MP) method [8]. Tree #1 out of 5 most parsimonious trees (length = 2,393) is shown. The consistency index is 0.477033, the retention index is 0.851434, and the composite index is 0.462543 (0.406163) for all sites and parsimony-informative sites (in parentheses). The MP tree was obtained using the Close-Neighbor-Interchange algorithm [11] with search level 3 [11, 31] in which the initial trees were obtained with the random addition of sequences (10 replicates). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths calculated using the average pathway method [11] and are in the units of the number of changes over the whole sequence. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the dataset. There were a total of 1,998 positions in the final dataset, out of which 712 were parsimony informative.

Table 3.

Percent identity of Tss-In and Tfr-In isolates of CMV with the other isolates reported worldwide based on RNA-3 genome

| S. no. | Strain/isolate | Accession | Host | Origin (country and year) | Subgroup | % Identitya | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV Tfr-In | CMV Tss-In | ||||||||||||

| RNA-3 | MP | IR | CP | RNA-3 | MP | IR | CP | ||||||

| 1 | Q-A | M21464 | – | Australia, 1988 | II | 71.8 | 79.5 | 58.1 | 77.4 | 95.9 | 98.5 | 93.2 | 98.3 |

| 2 | Ly-A | AF198103 | – | Australia, 1999 | II | 71.7 | 79.4 | 57.0 | 76.8 | 95.7 | 99.0 | 91.7 | 98.1 |

| 3 | Xb-C | AF268598 | Banana | China, 2000 | II | 72.4 | 79.9 | 59.1 | 77.2 | 94.2 | 98.4 | 90.6 | 97.1 |

| 4 | PE-C | AF268597 | Passion flower | China, 2000 | IB | 93.2 | 94.5 | 85.0 | 94.8 | 69.4 | 77.9 | 58.3 | 75.6 |

| 5 | M-C | AF268599 | – | China, 2000 | IA | 90.1 | 93.5 | 79.9 | 93.7 | 70.1 | 78.0 | 58.2 | 76.2 |

| 6 | PNb-C | DQ512476 | Pinellia ternata | China, 2006 | IC | 85.4 | 90.9 | 72.0 | 91.1 | 70.0 | 80.1 | 56.9 | 76.2 |

| 7 | phy-C | DQ412732 | – | China, 2006 | IB | 95.0 | 96.7 | 90.7 | 96.4 | 70.4 | 78.7 | 57.6 | 77.4 |

| 8 | pt-C | DQ409209 | Pinellia ternata | China, 2006 | IC | 85.5 | 90.8 | 72.3 | 91.1 | 69.9 | 80.0 | 57.2 | 76.2 |

| 9 | BX-C | DQ399550 | Pinellia ternata | China, 2006 | IC | 85.9 | 90.1 | 71.7 | 92.0 | 70.4 | 79.5 | 57.8 | 76.9 |

| 10 | Tsh-C | EF202597 | Tomato | China, 2006 | II | 72.4 | 79.5 | 59.7 | 77.2 | 95.5 | 98.6 | 91.1 | 98.3 |

| 11 | cb7-C | EF216867 | Tomato | China, 2007 | IB | 95.4 | 97.1 | 91.3 | 96.4 | 70.6 | 78.8 | 57.3 | 77.7 |

| 12 | YN-C | EF216865 | Brassica sps | China, 2007 | IB | 95.2 | 96.7 | 91.0 | 96.9 | 70.6 | 78.8 | 57.9 | 77.7 |

| 13 | CTL-C | EF213025 | Brassica chinensis | China, 2007 | IB | 92.5 | 94.6 | 84.2 | 93.1 | 69.6 | 77.4 | 58.1 | 76.8 |

| 14 | cah1-C | FJ268746 | Canna | China, 2008 | IB | 95.2 | 96.9 | 91.0 | 96.0 | 70.4 | 78.5 | 57.0 | 77.7 |

| 15 | PHz-C | EU723569 | Pinellia ternata | China, 2008 | IC | 85.7 | 90.9 | 72.3 | 91.4 | 70.1 | 80.1 | 57.2 | 76.3 |

| 16 | Te-C | EU665002 | Marigold | China, 2008 | II | 72.3 | 79.9 | 59.8 | 77.2 | 94.7 | 98.5 | 91.9 | 97.8 |

| 17 | Mb-C | GU002300 | Musa basjoo | China, 2009 | II | 71.2 | 79.9 | 60.4 | 77.1 | 94.4 | 98.0 | 90.6 | 97.2 |

| 18 | Trk7-H | L15336 | – | Hungary, 1994 | II | 71.9 | 79.4 | 59.5 | 76.3 | 95.1 | 99.0 | 89.6 | 97.4 |

| 19 | Ll-In | AJ831578 | Lily | India, 2005 | IA | 80.5 | 70.8 | 77.0 | 93.4 | 63.5 | 60.1 | 58.5 | 76.5 |

| 20 | Mp-In | EF178298 | Banana | India, 2006 | IB | 92.2 | 94.2 | 86.8 | 93.1 | 70.3 | 78.7 | 57.1 | 76.5 |

| 21 | Cm-In | EF153733 | Chrysanthemum | India, 2006 | IB | 92.1 | 93.6 | 87.8 | 91.3 | 69.7 | 78.7 | 56.0 | 75.3 |

| 22 | Tfr-In* | JF279606 | Tomato fruit | India, 2005 | IB | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 70.9 | 79.1 | 58.8 | 77.8 |

| 23 | Ts-In | EF153734 | Tomato | India, 2007 | IB | 97.5 | 97.4 | 90.0 | 98.7 | 70.2 | 77.6 | 55.0 | 77.7 |

| 24 | Jc-In | EF593026 | Jatropa curcus | India, 2007 | IB | 92.3 | 78.7 | 87.8 | 92.0 | 70.1 | 93.6 | 56.0 | 76.8 |

| 25 | Rs-In | EF593025 | Rauvolfia serpentina | India, 2007 | IB | 92.4 | 93.5 | 87.8 | 92.6 | 70.1 | 78.6 | 56.0 | 76.6 |

| 26 | Di-In | EF593024 | Datura innoxia | India, 2007 | IB | 92.0 | 92.9 | 87.8 | 91.9 | 69.7 | 78.2 | 56.0 | 75.9 |

| 27 | At-In | EF593023 | Amaranthus | India, 2007 | IB | 92.0 | 93.3 | 87.8 | 91.6 | 69.7 | 78.4 | 56.0 | 75.6 |

| 28 | Tss-In* | JF279605 | Tomato | India, 2008 | II | 70.9 | 79.1 | 58.8 | 77.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 29 | Dc-In | EU642567 | Carrot | India, 2008 | II | 71.3 | 78.2 | 59.4 | 76.0 | 94.6 | 97.5 | 91.6 | 95.7 |

| 30 | NDt-In | GU111229 | Tomato | India, 2009 | IB | 96.1 | 93.5 | 89.6 | 99.2 | 69.4 | 74.9 | 57.1 | 78.0 |

| 31 | B2-Ia | AB046951 | Banana | Indonesia, 2000 | IB | 92.2 | 93.8 | 88.7 | 93.4 | 70.0 | 77.4 | 56.2 | 78.1 |

| 32 | IA-Ia | AB042294 | – | Indonesia, 2000 | IB | 92.2 | 94.1 | 85.8 | 92.6 | 70.1 | 78.7 | 57.1 | 77.1 |

| 33 | Tfn-It | Y16926 | Tomato | Italy, 1998 | IB | 97.4 | 97.5 | 90.6 | 98.7 | 70.2 | 78.0 | 55.1 | 78.0 |

| 34 | Y1-J | D12499 | N. tabaccum | Japan, 1991 | IA | 90.3 | 94.0 | 79.6 | 95.1 | 70.2 | 78.4 | 57.9 | 77.1 |

| 35 | E5-J | D42080 | – | Japan, 1994 | IA | 90.4 | 94.4 | 79.6 | 94.3 | 70.2 | 78.1 | 58.1 | 76.3 |

| 36 | C7-2-J | D42079 | – | Japan, 1994 | IA | 89.6 | 93.5 | 81.8 | 94.2 | 69.3 | 78.2 | 58.4 | 77.2 |

| 37 | CS-J | D28489 | Limonium sinuatum | Japan, 1994 | IA | 90.0 | 93.2 | 79.3 | 94.9 | 71.0 | 79.1 | 58.7 | 77.7 |

| 38 | Pepo1-J | D28488 | Pepo | Japan, 1994 | IA | 90.2 | 93.6 | 79.6 | 94.6 | 70.7 | 78.4 | 58.8 | 77.8 |

| 39 | FT-J | D28487 | Tomato | Japan, 1994 | IA | 90.1 | 93.5 | 79.3 | 93.9 | 70.8 | 78.2 | 58.7 | 77.5 |

| 40 | N-J | D28486 | Limonium sinuatum | Japan, 1994 | IA | 90.5 | 93.6 | 79.6 | 95.4 | 70.4 | 78.6 | 58.2 | 78.0 |

| 41 | Y2-J | D83958 | – | Japan, 1996 | IA | 89.9 | 94.1 | 79.6 | 94.5 | 70.0 | 78.5 | 57.9 | 76.8 |

| 42 | MY17-J | AF103993 | – | Japan, 1998 | IA | 90.1 | 94.4 | 79.9 | 94.2 | 70.4 | 78.2 | 58.1 | 76.9 |

| 43 | SO-J | AF103992 | – | Japan, 1998 | IA | 90.4 | 93.8 | 79.3 | 94.5 | 71.0 | 78.8 | 58.4 | 77.5 |

| 44 | Pepo2-J | AF103991 | Pepo | Japan, 1998 | IA | 90.4 | 93.9 | 78.6 | 93.9 | 71.0 | 78.5 | 58.7 | 77.4 |

| 45 | IN-J | AB042294 | – | Japan, 2000 | IB | 92.5 | 94.1 | 85.8 | 92.6 | 70.3 | 78.7 | 58.3 | 77.1 |

| 46 | TN-J | AB176847 | Tomato | Japan, 2004 | II | 72.4 | 79.8 | 60.0 | 76.8 | 95.9 | 99.1 | 91.1 | 98.1 |

| 47 | MT-J | AB189917 | Tomato | Japan, 2004 | II | 72.1 | 79.7 | 58.8 | 77.1 | 95.5 | 98.6 | 91.3 | 97.5 |

| 48 | ON-J | AB248752 | Bitter gourd | Japan, 2006 | IA | 90.4 | 93.5 | 79.3 | 94.9 | 70.7 | 78.7 | 58.7 | 77.4 |

| 49 | PF-J | AB368501 | Tomato | Japan, 2007 | II | 72.2 | 79.2 | 60.0 | 77.5 | 95.4 | 98.4 | 90.4 | 98.0 |

| 50 | Y3-J | AB368498 | Cucumber | Japan, 2007 | IA | 89.6 | 93.2 | 79.9 | 95.1 | 70.6 | 78.6 | 58.7 | 77.5 |

| 50 | cap1-K | DQ777747 | Chilli | Korea, 2006 | IB | 90.8 | 93.8 | 78.1 | 92.6 | 70.1 | 77.8 | 56.0 | 76.3 |

| 52 | Cs-N | AY429437 | Groundnut | Netherlands, 2003 | IB | 90.6 | 93.5 | 78.7 | 92.9 | 69.7 | 76.9 | 54.8 | 78.3 |

| 53 | Ca-N | AY429432 | Groundnut | Netherlands, 2003 | IB | 91.1 | 93.8 | 79.1 | 93.4 | 69.9 | 77.3 | 55.6 | 78.0 |

| 54 | Ix-P | U20219 | Tomato | Philippines, 1995 | IB | 91.2 | 94.1 | 82.1 | 92.9 | 68.5 | 76.5 | 54.4 | 76.3 |

| 55 | Mf-Sk | AJ276481 | – | South Korea, 2000 | IA | 90.7 | 94.6 | 79.3 | 94.9 | 70.7 | 78.4 | 58.7 | 77.2 |

| 56 | Li-Sk | AJ495841 | Lily | South Korea, 2002 | IA | 89.5 | 94.6 | 77.7 | 93.7 | 70.0 | 77.9 | 58.8 | 76.6 |

| 57 | p-Sk | AB369272 | Pepper | South Korea, 2007 | IA | 90.8 | 94.0 | 79.9 | 94.9 | 70.2 | 77.9 | 58.4 | 76.5 |

| 58 | pepY-Sk | AB369271 | N. benthamiana | South Korea, 2007 | IA | 90.6 | 93.6 | 79.6 | 95.1 | 70.8 | 79.0 | 59.0 | 77.5 |

| 59 | V-Sk | AB369270 | N. benthamiana | South Korea, 2007 | IA | 90.2 | 93.3 | 78.9 | 93.7 | 70.5 | 78.4 | 58.1 | 76.8 |

| 60 | Z-Sk | AB369269 | N. benthamiana | South Korea, 2007 | IA | 90.8 | 93.9 | 79.3 | 95.4 | 70.9 | 79.1 | 58.4 | 77.4 |

| 61 | paf-Sk | AB369273 | N. benthamiana | South Korea, 2007 | IA | 90.3 | 94.2 | 79.9 | 94.8 | 70.1 | 77.2 | 58.7 | 76.8 |

| 62 | Ri8-S | AM183119 | Tomato | Spain, 2006 | IA | 89.5 | 94.0 | 79.9 | 94.6 | 70.2 | 78.2 | 58.4 | 76.9 |

| 63 | p1-1-S | AM183116 | Tomato | Spain, 2006 | IB | 96.7 | 97.0 | 90.6 | 98.1 | 70.4 | 78.0 | 56.0 | 77.8 |

| 64 | M48-T | D49496 | – | Taiwan, 1995 | IB | 90.1 | 93.8 | 78.9 | 91.6 | 70.0 | 78.4 | 58.1 | 76.2 |

| 65 | M-U | D10539 | – | USA, 1992 | IA | 90.0 | 93.6 | 79.9 | 93.4 | 70.1 | 78.1 | 58.4 | 75.9 |

| 66 | Fny-U | NC_001440 | Summer squash | USA, 1992 | IA | 90.6 | 94.0 | 80.2 | 94.9 | 70.2 | 78.1 | 58.1 | 76.8 |

| 67 | Ls-U | AF127976 | – | USA, 1999 | II | 71.6 | 79.3 | 58.1 | 77.1 | 95.9 | 98.8 | 93.2 | 98.1 |

aRNA-3 and IR (intergenic region) are based on nucleotide sequence. MP (movement protein) and CP (coat protein) based on amino acid sequence. Subgroups are based on sequence identity in complete RNA-3

* Present study

Subgroup Specific Detection of CMV

Two pairs of primers, BM53F and BM54R specific for subgroup-I and BM51F and BM52R specific for subgroup-II were designed based on the multiple alignment of full length sequences of RNA-3 of the isolates from both the subgroups. Subgroup specific detection of CMV was conducted by RT-PCR as described previously using an annealing temperature of 54°C.

To check the specificity of these primers for the group specific detection of CMV, was conducted by RT-PCR using experimental samples of tomato plants inoculated with Tfr-In isolate (subgroup-I) and Tss-In isolate (subgroup-II) in the greenhouse. Further, group-specific detection was conducted in field samples of tomato from IARI, New Delhi, and cucurbit and chilli from Bangalore.

Results

CMV Isolates and Host Reactions

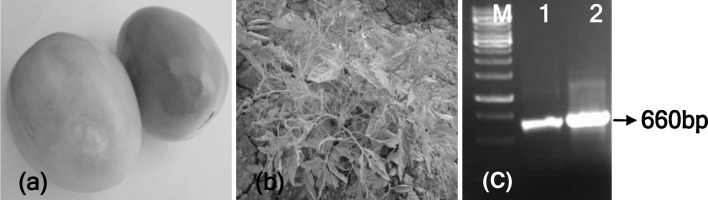

A total of five isolates were obtained from cucumber, muskmelon, tobacco and tomato originating from northern, southern and central-western parts of India (Table 1). Tfr-In was isolated from tomato fruit showing grey patches (Fig. 2a) in commercial field at Aurangabad. Another tomato isolate, Tss-In showed shoe-string (Fig. 2b), a distinct symptom-type in the experimental field at IARI, New Delhi. Three other isolates Ban-In, Pun-In and Bal-In showed mottling or mosaic symptoms on tobacco, cucumber and muskmelon, respectively under field conditions. Under greenhouse conditions following sap transmission, Tfr-In, Ban-In, Pun-In and Bal-In isolates produced chlorotic spots and mottling symptoms on tomato, whereas, Tss-In isolate produced shoe-string symptoms. On cucumber, all the isolates produced mosaic mottling and on N. glutinosa, severe mosaic blistering symptoms following sap transmission. Host reactions of most of the isolates were similar except Tss-In isolate, which produced distinct symptoms on tomato.

Fig. 2.

Symptoms of CMV isolates. a Tomato fruit (Tfr) showing grey patches from where Tfr-In isolate was obtained. b Tomato plant showing shoe-string (Tss) symptoms from where Tss-In was isolated. c RT-PCR using primers (BM05F and BM06R) based on CP gene shows detection of CMV in samples from a (lane 1) and b (lane 2)

Genome Organization and Phylogenetic Relationships

RT-PCR using CP gene primers, BM05F and BM06R resulted in amplification of 660 bp DNA fragments in all the five isolates. Sequence analysis of complete CP of these isolates showed that four isolates, Tfr-In, Ban-In, Pun-In and Bal-In (JF279606, JF279607, JF279608, JF279609) were closely related with 93–98% sequence identity, whereas, Tss-In showed significant sequence diversity sharing only 77% identity with the other four isolates. The complete nucleotide sequence of RNA-3 of Tfr-In and Tss-In isolates showed that they were 2,214 and 2,179 nucleotides (nt) long, respectively. The RNA-3 genome contained 5′ UTR (Tss-In: 1–63 nt; Tfr-In: 1–111 nt) followed by ORF 3a (Tss-In: 64–903 nt; Tfr-In: 112–951 nt) encoding putative MP, IR (Tss-In: 904–1,199 nt; Tfr-In: 952–1,255 nt), ORF 3b (Tss-In: 1,200–1,856 nt; Tfr-In: 1,256–1,912 nt) encoding CP and 3′ UTR (Tss-In: 1,857–2,178 nt; Tfr-In: 1,913–2,214 nt). The RNA-3 genome organization of Tfr-In and Tss-In was similar to other isolates of CMV.

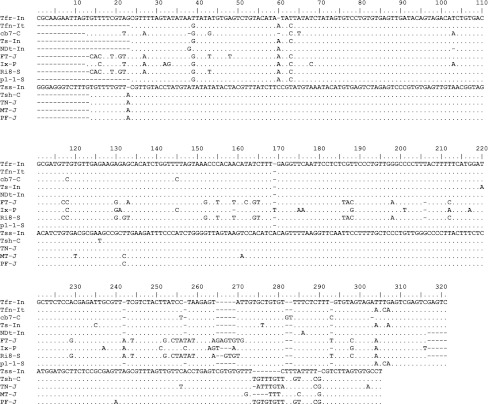

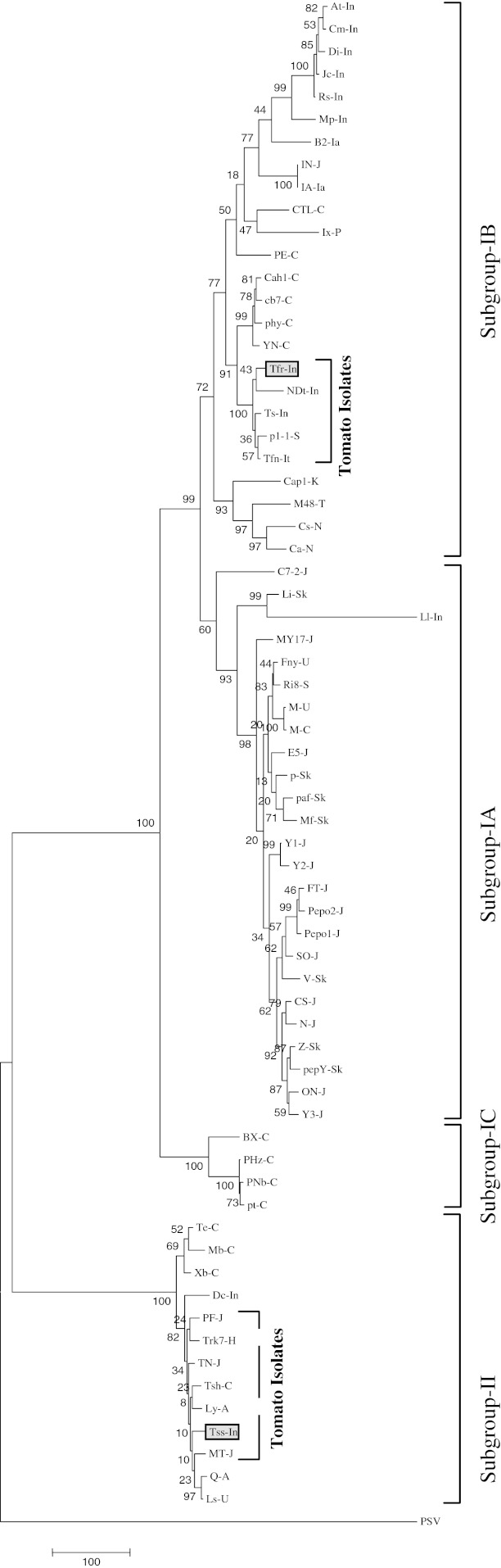

The complete RNA-3 sequence comparison of these two isolates with 65 other isolates of CMV reported world over revealed that Tfr-In was very closely related to subgroup-I isolates sharing a sequence identity of 80.5–97.5%, whereas, it was distantly related to the members under subgroup-II sharing only 70.9–72.4% sequence identity. Interestingly Tss-In isolate was closely related to the members under the CMV subgroup-II sharing of 94.2–95.9% sequence identity and distantly related with the members under subgroup-I sharing only 68.5–71% sequence identity. Tfr-In shared only 70.9% sequence identity with Tss-In in RNA-3. The CP and MP of these two isolates shared 77.8 and 79.1%, respectively and IR was more diverse sharing only 58.8% sequence identity. Comparison of IR sequence of tomato isolates showed that subgroup-II isolates contain sequence diversity at 3′ end of IR, whereas majority of subgroup-I isolates showed variability in both termini but three isolates (FT-J, Ix-P and Ri8-S) showed variability throughout the IR (Fig. 4). Phylogenetic analysis based on complete RNA-3 sequence of 67 isolates showed four distinct evolutionary subgroups-IA, IB, IC and II (Fig. 3). Tfr-In isolate clustered with the four tomato isolates from India, Italy and Spain under the subgroup-IB whereas, Tss-In isolate clustered with four other tomato isolates from Japan and China with the members under subgroup-II.

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide sequence alignment of IRs of Tfr-In with subgroup-I and Tss-In with subgroup-II tomato isolates of CMV reported from Asia and Europe. Isolate designations are in Table 3

Fig. 3.

Parsimonious tree based on nucleotide sequence of complete RNA-3 genome of CMV isolates showing evolutionary clustering of Indian isolates with globally distributed isolates. The MP tree was obtained using the Close-Neighbor-Interchange algorithm with search level in which the initial trees were obtained with the random addition of sequences (10 replicates). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths calculated using the average pathway method and are in the units of the number of changes over the whole sequence. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA4. Isolates description as in Table 3

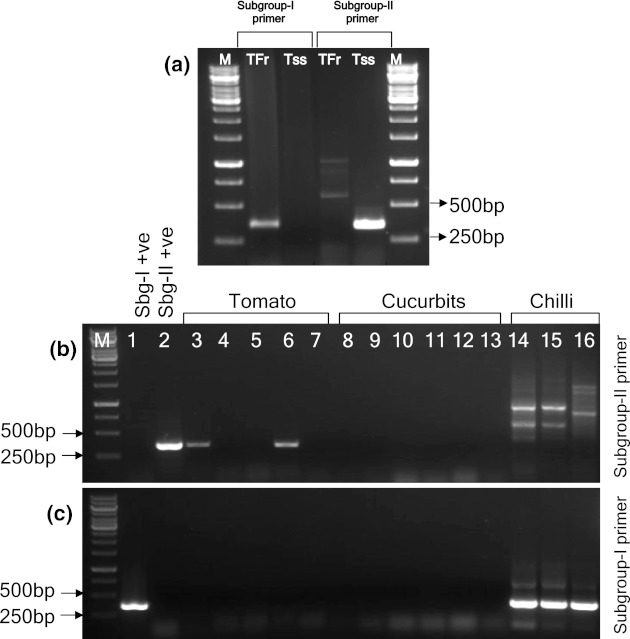

Subgroup Specific Detection

As shown in the Fig. 5a, the RT-PCR using subgroup-I specific primers, BM53F and BM54R resulted in specific amplification of ~386 bp with Tfr-In isolate and no amplification with Tss-In isolate, whereas subgroup-II specific primers, BM51F and BM52R gave a specific amplification of ~376 bp with Tss-In isolate. Whereas, the common primers, BM05F and BM06R resulted in amplification of both Tfr-In and Tss-In isolates (Fig. 2c). Fourteen field samples were tested by using both the subgroup specific primers, of which two out of five tomato samples collected from experimental field of IARI, New Delhi showed specific amplification with only subgroup-II primers (Fig. 5b). The cucurbit samples (muskmelon, cucumber, snake gourd and bitter gourd) collected from Bangalore did not show any specific amplification with both the subgroup-I and -II primers. Whereas, the chilli samples from Bangalore showed amplification with subgroup-I specific primers but not with subgroup-II specific primers (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Subgroup specific detection of CMV by RT-PCR. a Standard experimental samples from greenhouse by using both subgroup-I and subgroup-II primers. b Field samples by using subgroup-II primers (BM51F and BM52R) (c) with subgroup-I primers (BM53F and BM54R). M 1 kb ladder, lane 1 Tfr-In showing −ve amplification, lane 2 Tss-In isolate showing +ve amplification, lanes 3–7 tomato field samples, lanes 8–13 cucurbit field samples (lanes 8, 9 and 10 muskmelon; lane 11 cucumber; lane 12 snakegourd; lane 13 bitter gourd), lanes 14–16 chilli field samples

Discussion

The five isolates of CMV collected from different crops and geographical locations in India were studied for their host reactions and CP gene variability. Among these isolates, two distinct tomato isolates, Tfr-In and Tss-In were characterised based on complete sequence of RNA-3 genome. The sequence information was utilized to develop RT-PCR based subgroup specific diagnosis of CMV.

The full length RNA-3 of Tfr-In is 35 nucleotides longer than that of Tss-In, and their sequence were significantly different (70.9% similarity). The IR of the two isolates was more heterogeneous compared to the other part of the genome, the multiple alignment of both the isolates showed maximum difference at beginning (70 nucleotides) and at the terminal (100 nucleotides) portion of the IR. The complete RNA-3 sequence of Tss-In and Tfr-In were compared with 65 CMV isolates which were reported from 14 different countries and 25 plant species during last 22 years. Phylogenetic analysis of these isolate based on complete RNA-3 showed two major subgroup-I and -II. The subgroup-I was further divided into three major subclades-IA, IB and IC. Similar clustering pattern of these isolates was observed based on CP sequence (data not shown). Several isolates of CMV have been reported from several countries in the world and they are classified into three subgroups, -IA, -IB and -II based on phylogenetic analysis of CP gene and 5′ UTR sequence [20]. The phylogenetic analysis revealed an additional subclade IC within the subgroup-I was found to contain four isolates (pH2-C, pNb-C, pt-C and BX-C) reported from Pinellia ternata from China during 2006–2008 [34]. CMV is a common viral pathogen in tomato. Complete RNA-3 sequence of 14 isolates of CMV from tomato are available from China, Japan, India, Philippines, Italy and Spain, and they are distributed in both subgroup-I and -II. The majority of CMV isolates in India are grouped under subgroup-IB. Interestingly, Tfr-In and other tomato isolates from India clustered together under subgroup-IB. Under subgroup-II, Tss-In clustered together with six other tomato isolates reported from Hungary, Japan and China.

Shoe-string symptoms caused by CMV has been reported from India, which was grouped under subgroup-IB [14], whereas CMV isolated from tomato showing shoe-string in Pakistan [2] and Australia [30] were grouped under subgroup-IA and -IB, respectively. In the present study, CMV isolate showing shoe-string in tomato (Tss-In) is grouped under subgroup-II. It seems shoe-string symptom phenotype is not consistent with phylogenetic grouping. Several studies showed subgroup-IB type of CMV is predominant in India [10, 14, 16, 23, 27]. However, only a few Indian isolates were reported under subgroup-II. Subgroup-II CMV causing severe mosaic and stunting in tomato was reported from southern India based on MspI restriction site on CP gene [29]. Genome sequence information of this isolate is not available. The present study for the first time described complete RNA-3 genome sequence of a CMV strain under subgroup-II causing shoe-string symptoms in tomato in India. In addition to tomato, subgroup-II isolates were also reported in India infecting carrot (EU642567), lily [25] and geranium [32].

Previously, RT-PCR based detection of CMV subgroup-I and -II was achieved based on MspI restriction pattern [18, 26] and immunocapture RT-PCR [35] using CP gene. In the present study, molecular detection by RT-PCR was developed to detect CMV subgroups in Indian population of CMV. The complete sequence comparison of Tfr-In and Tss-In revealed maximum sequence diversity in the flanking IR regions that include the 3′ region of MP ORF and 5′ region of CP ORF. Therefore, subgroup specific primers were designed based on sequence from the above mentioned regions and specific amplification of Tfr-In and Tss-In representing subgroup-I and subgroup-II, respectively, was obtained. Further, the specificity of detection was verified by using field samples from different crops.

CMV is known to cause severe damage in tomato crops worldwide showing different types of symptoms like shoe-string, mosaic, necrosis, fruit necrosis and stunting. CMV has been reported to cause fruit necrosis in tomato in Hungary [22]. In Spain, subgroup-IB CMV causes symptomless leaves and discolouration of fruit [3]. In the present study, for the first time a subgroup-IB CMV causing grey patches on tomato fruit has been described and complete RNA-3 genome sequence has been characterized from India. Characterisation of another distinct strain of CMV causing shoe-string in the present study and severe mosaic in the previous study [29] provided evidence that tomato in India is affected by multiple strains of CMV.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

References

- 1.Aglave BA, Krishnareddy M, Patil FS, Andhale MS. Molecular identification of a virus causing banana chlorosis disease from Marathwada region. Int J Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;3:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhtar KP, Ryu KH, Saleem MY, Asghar M, Jamil FF, Haq MA. Occurrence of Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup IA in tomato in Pakistan. J Plant Dis Prot. 2008;115:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aramburu J, Galipienso L, Lopez C. Reappearance of Cucumber mosaic virus isolates belonging to subgroup IB in tomato plants in North-eastern Spain. J Phytopathol. 2007;155:513–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2007.01267.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhargava KS. Some properties of four strains of Cucumber mosaic virus. Ann Appl Biol. 1951;38:377–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1951.tb07812.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhat AI, Hareesh PS, Madhubala R. Sequencing of coat protein gene of an isolate of Cucumber mosaic virus infecting black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) in India. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2005;14:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding SW, Anderson BJ, Haase HR, Symons RH. New overlapping gene encoded by the cucumber mosaic virus genome. Virology. 1994;198:593–601. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodds JA, Morris TJ, Jordan RL. Plant viral double-stranded RNA. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1984;22:151–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.22.090184.001055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eck RV, Dayhoff MO. Atlas of protein sequence and structure. Silver Springs: National Biomedical Research Foundation; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kosaka Y, Hanada K, Fukunishi T, Tochihara H. Cucumber mosaic virus isolate causing tomato necrotic disease in Kyoto prefecture. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1989;55:229–232. doi: 10.3186/jjphytopath.55.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madhubala R, Bhadramurthy V, Bhat AI, Hareesh PS, Retheesh ST, Bhai RS. Occurrence of Cucumber mosaic virus on vanilla (Vanilla planifolia Andrews) in India. J Biosci. 2005;30:339–350. doi: 10.1007/BF02703671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nei M, Kumar S. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 352.

- 12.Palukaitis P, Zaitlin M. Replicase-mediated resistance to plant virus disease. Adv Virus Res. 1997;48:349–377. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palukaitis P, Roossinck MJ, Dietzgen RG, Francki RIB. Cucumber mosaic virus. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:281–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratap D, Kumar S, Raj SK. First molecular identification of a Cucumber mosaic virus isolate causing shoestring symptoms on tomato in India. Aust Plant Dis Notes. 2008;3:57–58. doi: 10.1071/DN08023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raj SK, Srivastava A, Chandra G, Singh BP. Characterisation of Cucumber mosaic virus isolate infecting Gladiolus cultivars and comparative analysis of serological and molecular methods for sensitive diagnosis. Curr Sci. 2002;83:1132–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raj SK, Kumar S, Pratap D, Vishnoi R, Snehi SK. Natural Occurrence of Cucumber mosaic virus on Rauvolfia serpentina, a new record. Plant Dis. 2007;91:322. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-91-3-0322C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raj SK, Kumar S, Snehi SK. First Report of Cucumber mosaic virus on Jatropha curcas in India. Plant Dis. 2008;92:171. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-92-1-0171C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizos H, Gunn LV, Pares RD, Gillings RM. Differentiation of Cucumber mosaic virus isolates using the polymerase chain reaction. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2099–2103. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roossinck MJ. Cucumber mosaic virus, a model for RNA virus evolution. Mol Plant Pathol. 2001;2:59–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2001.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roossinck MJ, Zhang L, Hellwald KH. Rearrangements in the 5′ nontranslated region and phylogenetic analyses of Cucumber mosaic virus RNA 3 indicate radial evolution of three subgroups. J Virol. 1999;73:6752–6758. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6752-6758.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roossinck MJ, Bujarski J, Ding SW, Hajimorad R, Hanada K, Scott S, Tousignant M. Bromoviridae. In: van Regenmortel MHV, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Carstens EB, Estes MK, Lemon SM, Maniloff J, Mayo MA, McGeoch DJ, Pringle CR, Wickner RB, editors. Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Seventh Report of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 923–935. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salamon P, Gajdos L, Balogh P, Solymoss E, Varro P, Milotay P, Kiss L, Salanki K. Isolation of a virulent strain of Cucumber mosaic virus from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) affected by fruit necrosis. Kertgazdasag Hortic. 2005;(special):155–61.

- 23.Samad A, Raj SK, Srivastava A, Chandra G, Ajayakumar PV, Zaim M, Singh BP. Characterization of a Cucumber mosaic virus isolates infecting Egyptian henbane (Hyoscyamus muticus L.) in India. Acta Virol. 2000;44:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning, a laboratory manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma A, Mahinghara BK, Singh AK, Kulshrestha S, Raikhy G, Singh L, Verma N, Ram R, Zaidi AA. Identification, detection and frequency of Lily viruses in northern India. Sci Hortic. 2005;106:213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2005.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh Z, Jones RA, Jones MGK. Identification of Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup I isolates from banana plants affected by infectious chlorosis disease using RT-PCR. Plant Dis. 1995;79:716–731. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srivastava A, Raj SK. High molecular similarity among Indian isolates of Cucumber mosaic virus suggests a common origin. Curr Sci. 2004;87:1126–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivastava A, Chandra G, Raj SK. Coat protein and movement protein gene based molecular characterization of Amaranthus strain of Cucumber mosaic virus. Acta Virol. 2004;48:229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudhakar N, Prasad DN, Mohan N, Murugesan K. First report of Cucumber mosaic virus subgroup II infecting Lycopersicon esculentum in India. Plant Dis. 2006;90:1457. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-1457B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sulistyowati E, Mitter N, Bastiaan-Net S, Roossinck MJ, Dietzgen RG. Host range, symptom expression and RNA 3 sequence analyses of six Australian strains of Cucumber mosaic virus. Aust Plant Pathol. 2004;33:505–512. doi: 10.1071/AP04054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verma N, Mahinghara BK, Ram R, Zaidi AA. Coat protein sequence shows that Cucumber mosaic virus isolate from geraniums (Pelargonium Sp.) belongs to subgroup II. J Biosci. 2006;31:47–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02705234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahyuni WS, Dietzgen RG, Hanadat K, Francki RB. Serological and biological variation between and within subgroup I and II strains of Cucumber mosaic virus. Plant Pathol. 1992;41:282–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.1992.tb02350.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang HY, Zhang HR, Du ZY, Zeng R, Chen J. Evolutionary characterization of two Cucumber mosaic virus isolates infecting Pinellia ternata of Araceae family. 2009; http://www.paper.edu.cn/index.php/default/en_releasepaper/downPaper/200902-1424.

- 35.Yu C, Wu J, Zhou X. Detection and sub grouping of Cucumber mosaic virus isolates by TAS-ELISA and immunocapture RT-PCR. J Virol Methods. 2005;123:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]