Abstract

The family Nodaviridae include the genera Alphanodavirus and the Betanodavirus which are non-enveloped, single stranded RNA viruses. Alphanodavirus include the insect viruses while betanodavirus include species that are responsible for causing disease outbreaks in hatchery-reared larvae and juveniles of a wide variety of marine and freshwater fish throughout the world and has impacted fish culture over the last decade. According to International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, the genus Betanodavirus comprises four recognized species viz barfin flounder nervous necrosis virus, red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus (RGNNV), striped jack nervous necrosis virus and tiger puffer nervous necrosis virus with the RGNNV being the most common. The viruses are distributed worldwide having been recorded in Southeast Asia, Mediterranean countries, United Kingdom, North America and Australia. The disease has been reported by different names such as viral nervous necrosis, fish encephalitis, viral encephalopathy and retinopathy by various investigators. The virus is composed of two segments designated RNA1 and RNA2 and sometimes possesses an additional segment designated RNA3. However, genome arrangement of the virus can vary from strain to strain. The virus is diagnosed by microscopy and other rapid and sensitive molecular methods as well as immunological assays. Several cell lines have been developed for the virus propagation and study of infection mechanism. Control of nodavirus infection is a serious issue in aquaculture industry since it is responsible for huge economic losses. In combination with other management practices, vaccination of fish would be a useful strategy to control the disease.

Keywords: Betanodavirus, Fish, Genome arrangement, Diagnosis, Disease control, Vaccination

Introduction

Aquaculture is recognized as one of the fastest growing industry among the food producing industries and is expected to contribute to the reduction in gap between demand and supply of fishery products [33]. The marine aquaculture fish production has increased rapidly during the past several years due to their higher market demand and economic value. However, rapid expansion and intensification of aquaculture has led to disease outbreaks. Among the infectious diseases, viral diseases are the most serious since they cause severe losses to fish aquaculture production. Many viral diseases of fish have been reported worldwide [66, 92, 108] of which infection caused by betanodavirus is a major concern. The virus has emerged as a major constraint to fish culture and is responsible for catastrophic losses reported worldwide. The disease is associated with high mortalities (up to 100 %) particularly in larvae and juvenile fish species in various part of the world including Europe, North America, Asia, Japan and Australia [107].

Betanodavirus infection was first reported in Lates calcarifer (Barramundi) in Australia [41] and an identical disease was also observed later in European seabass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.) in Caribbean [11]. The infections are also reported in hatchery-reared Japanese parrotfish, Oplegnathus fasciatus in Japan [122] and Barramundi larvae (L. calcarifer) in Australia [42]. Several reports are also documented from turbot Scophthalmus maximus [12], European seabass D. labrax [13] redspotted grouper Epinephelus akaara [80], and striped jack Pseudocaranx dentex [81]. The infections can occur in a variety of cultured warm water and cold water marine fish species [83, 86] as well as some fresh water fish [52, 53]. Presently ~40 species of fish species are known to be affected with betanodavirus infection [28, 83] with the most recent one being freshwater guppy [23, 52, 53] and aquarium fish such as gold fish and rainbow shark [62]. Therefore, it is very necessary to detect the virus before any clinical signs appear. In addition to microscopic analysis, many sensitive and rapid molecular techniques are available [36, 64, 89, 113, 117]. Paying attention to the control measures such as the new generation vaccine strategies is important together with adoption of better management approaches. Current review will describe about this virus infection, diagnosis of the disease and the control measures.

Aetiology

Betanodavirus, a single stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus, is responsible for serious problem in cultured fish. Huge mass mortality due to this virus has been recognized since 1980s around the world. The virus in particular affects larval and juvenile stages of fish. This is a non-enveloped virus with an icosahedral capsid (triangulation number = 3) ranging from 25 to 34 nm in diameter. The capsid consists of 32 capsomeres. The virus is mainly composed of two segments (RNA1 and RNA2). The RNA1 segment encodes two non-structural viral replicase proteins, while the RNA2 encodes the structural capsid protein. The disease has been reported by a variety of names such as viral nerve necrosis (VNN) [122], fish encephalitis virus [12] and viral encephalopathy and retinopathy [83, 93]. The virus is found to be affecting both cold water and warm water fishes and reported throughout the world [83]. It was initially believed that the virus was a parvovirus or a picornavirus. By 1990 the nomenclature of the virus was confirmed and was placed in the family Nodaviridae, genus Betanodavirus. Betanodavirus is a distinct group from the insect nodaviruses (Alphanodaviruses) [90] in the 7th report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses [8, 86]. The recognized members are: barfin flounder nervous necrosis virus (BFNNV), red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus (RGNNV), striped jack nervous necrosis virus (SJNNV) and tiger puffer nervous necrosis virus (TPNNV) and RGNNV is most widely distributed [64, 90, 91, 107].

Occurrence and Distribution

Betanodavirus infections have been reported in all continents except South America [65, 83, 86] especially in regions where intensive culture of marine species is rampant. These include, south and east Asia (Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei, India, China), Oceania (Australia, Tahiti), the Mediterranean (Israel, Croatia, Bosnia, Greece, Malta, Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, Tunisia), the UK, Scandinavia (Norway), and North America (USA, Canada) [9, 21, 25, 30, 86, 94, 127]. Betanodavirus infection is one of the most devastating diseases of marine aquaculture and also represents a threat to wild fish populations because of its high infectivity and broad host range [94]. Initially, the infection is observed in 19 fish species (belonging to 10 families, 3 orders), including Japanese parrotfish, redspotted grouper, striped jack, Barramundi, turbot, and European seabass [82]. Later, 32 more species (16 families, 5 orders) is listed which have been recorded as hosts for this virus [83].

More recently, around 40 host species have been reported (22 families, 8 orders) which includes Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua); thread-sail filefish (Stephanolepis cirrhifer); spotted wolf fish (Anarhichas minor) sturgeon Acipenser sp., turbot (S. maximus); Chinese catfish (Parasilurus asotus), guppy (Poecilia reticulate), dragon grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus), Japanese tilefish (Branchiostegus japonicas), firespot snapper (Lutjanuserythropterus), bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus); sevenband grouper (Epinephelus septemfasciatus), Golden pompano, (Trachinotus blochii) (E. septemfasciatus) and redspotted grouper (E. akaara) [46, 54, 69, 86, 98, 100, 103]. Larval or juvenile stages are more prone to this viral infection, but significant mortality can also occur in older fish up to production-size as in European seabass, sevenband grouper, humpback grouper Cromileptes altivelis and Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus [4, 37, 71, 83, 86, 125]. Infections are also reported in freshwater fish, such as Chinese catfish (P. asotus); Australia catfish (Tandanus tandanus); Barramundi (L. calcarifer); Medaka (Oryzias latipes); guppy (Poicelia reticulata) and zebrafish (Danio rerio) [5, 22, 52, 53, 62, 63, 76]. Several experimental infection studies have demonstrated that both marine and fresh water finfish are susceptible to betanodavirus infection [23, 38, 39, 52, 53, 63]. It has been seen that Asian seabass juveniles are more susceptible to betanodavirus from 10 day onwards with high mortalities of 80 % and smaller sized fish are more prone to the virus than bigger sized fish in the cages. This could be due to attributed also to various stress factors like overcrowding in the cages, cannibalistic nature of seabass, size grading procedure applied in cage culture system etc. (Shetty et al. unpublished data). Among the betanodavirus genotypes, host range of SJNNV and TPNNV are limited to striped jack (P. dentex) and tiger puffer (Takifugu rubripes), respectively whereas BFNNV genotype has been isolated from cold water species, such as Barfin flounder (Verasper moseri) and Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus). RGNNV genotype was found to have a broad host range causing disease among a variety of warm water fish species, particularly groupers and seabass. This has led to discussions on possible host specificity and temperature dependence in betanodavirus strains [4, 22].

Clinical Signs

Classical signs of disease are most commonly observed in larval and juvenile fishes since they are commonly affected [82] and sometimes in adult fish [37, 71, 103]. Diseased fish show various clinical symptoms which include reduced appetite, emaciation, colour change (darkening), abnormal (whirling) swimming pattern, neurological dysfunction, exophthalmia, swim bladder hyperinflation, floating belly up with inflation of swim bladder, anorexia and gas accumulation and extensive mortality (Fig. 1) [6, 37, 38, 49, 64, 77, 85, 97, 102, 117, 126], (Shetty et al. unpublished data). Gross lesions are uncommon, but overinflation of the swimbladder has been observed [37, 92]. Several investigators have confirmed the presence of betanodavirus in fish without evidence of any disease signs as in brown meagre (Sciaena umbra) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) [9, 29, 43, 48].

Fig. 1.

Asian seabass (L. calcarifer) juveniles infected with nodavirus. A: Arrow shows dark coloration on the body surface. B & C: Highly emaciated infected fish

Genome Organization

The betanodavirus genome is organized as a bisegmented positive sense ssRNA. Recent complete genome sequence of the virus reveals that the genome size is 4.5 kb in which the larger segment, RNA1 (3,103 nt) with a G+C content of 49.6 %, encodes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (protein A) flanked by a 78 nt 5′-nontranslated regions (NTR) and a 77 nt 3′-NTR region. The open reading frame (ORF) contains a 982-amino-acid with a calculated molecular mass of 110.74 kDa. On the other hand, the smaller segment, RNA2 (1433 nt) having a G+C content of 53.24 % contains a 338-amino-acid major ORF which encodes the coat protein with a calculated molecular mass of 37.059 kDa flanked by 26 nt 5′-NTR and a 390 nt 3′-NTR [19, 75, 107, 118]. RNA2 forms a major ORF of capsid protein and consists of a highly conserved region and a variable region. In addition to this, RNA3, a sub genomic RNA (371 nt) has a 62 % G+C composition, containing an ORF encoding a peptide of 75 amino-acids corresponding to a hypothetical B2 protein which is a non-structural protein having a suppressor function for post-transcriptional gene silencing [19, 34, 61, 110]. RNA3 is formed only in infected cells and is not packaged into the viral particles (not in chronically infected fish) [79, 90, 110] and is transcribed from the 3′ end of RNA1. However, the genome arrangement of the virus can vary from strain to strain. To substantiate and understand this, phylogenetic analysis was carried out based on the gene encoding viral coat protein for various viral strains [16, 45, 90, 91]. For example, the sequence similarities among SJNNV and the coat protein gene from different fish VNN viruses was found to be 75.8 % or greater at the nucleotide level and 80.9 % or greater at the amino-acid level [90]. In the fish betanodaviruses, there is a highly conserved region of 134 amino-acids with a sequence similarity of 92.5 % or greater which is not found in the coat protein of insect nodaviruses [90].

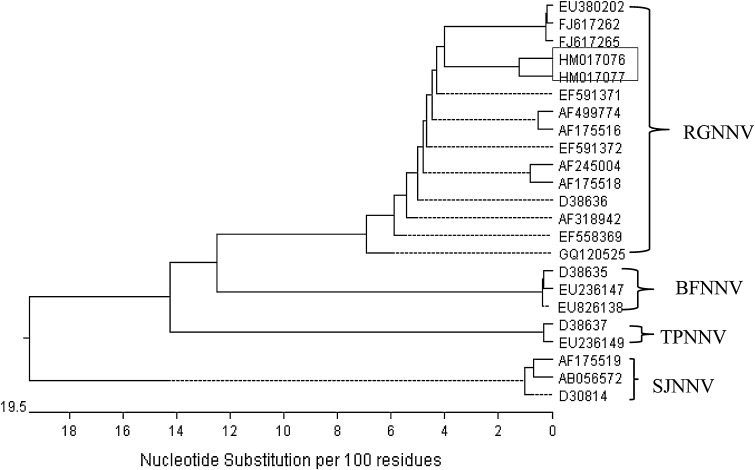

More recently, phylogenetic analysis based on the sequence of both RNA1 and RNA2 from 120 viral strains from different countries of Europe was performed. Viruses sampled from individual countries tended to cluster together thus indicating a major geographic subdivision among betanodaviruses [94]. Our results on the analysis of the sequence of T4 region of the nodaviral RNA2 coat protein of Indian strain from Asian seabass (L. calcarifer) show high similarity (>90 %) with the other Asian strains and belongs to RGNNV which is the widely distributed genotype of all the known genotypes of betanodavirus (Fig. 2) (Shetty et al. unpublished data). Analysis also suggest that strain variation of the virus is not related to the host-dependent evolution and/or geography. Betanodavirus appear to adapt easily to other fish species [16].

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from the variable region of coat protein sequences of betanodaviruses using MegAlign program (Windows version 5.05, DNASTAR, USA). Accession numbers: HM017076, HM017077 [Asian seabass (L. calcarifer), India] are the coat protein sequences generated in our lab and shown in rectanglular box (Shetty et al. unpublished data); EU380202, FJ617262, GQ120525: [Asian seabass (L. calcarifer), Malaysia]; AF245004: [Giant Grouper (E. lanceolatus), Taiwan]; EF591371 and EF591372: [Barramundi (L. calcarifer), Australia]; D38636: [Redspotted grouper (E. akaara), Japan]; EF558369: [Redspotted grouper (E. akaara), China]; AF499774: [Guppy (P. reticulate), Singapore]; AF175518: [Brownspotted Grouper (E. malabaricus), Thailand]; AF175516: [Barramundi (L. calcarifer), Singapore]; AF318942: [Greasy grouper (E. tauvina), Singapore]; D38637 and EU236149: [Tiger puffer (Takifugu rupripes), Japan]; D38635, EU236147 and EU826138: [Barfin flounder (V. moseri), Japan]; AF175519, D30814 and AB056572: [Striped jack (P. dentex), Japan]. The distance between sequences is represented by the length of each pair of branch and the unit below the tree indicates the number of substitution events

Diagnosis of Betanodavirus

Clinical signs of betanodavirus infection are characteristic in larvae and fry and the indication of disease onset. However, it is important to diagnose the preclinical state before disease occurs so that necessary good health management measures can be undertaken to avoid the viral disease outbreak. Diagnostic assays for betanodavirus are important to identify any outbreaks of infection and to screening of the broodstock that may be act as carriers [113]. Ideally, the methods for diagnosis should be rapid, sensitive, specific and reliable. Various methods are available for betanodavirus diagnosis such as microscopy, molecular, immunological and cell culture methods.

Microscopy

Microscopic analysis of any lesion sites produced by betanodavirus provides useful information in order to understand the nature of infection. Although the virus is neurotropic, it may replicate in other tissues such as the liver and spleen. Typical histopathological lesions include severe widespread degeneration and vacuolation throughout the central nervous system (CNS) of the fish and all retinal layers. The bipolar and ganglion cell retinal layers exhibit the most obvious vacuolation. Gliosis is also a common finding in the CNS. Vacuolation is usually greater in the grey matter of the optic tectum and cerebellum and there is often involvement of Purkinje cells. Vacuolation can also be seen in the white matter, adjacent to the ventricles [112]. Immunohistochemistry study reveals the location of immunopositive cells and shows that the virus favours neural cells which are in the early stages of proliferation. This indicates that the virus enters the CNS along nerves and blood vessels during the viraemic stage of the disease [64, 71]. The virus also can be detected by immunofluoresence microscopy by using monoclonal antibody [101]. Virions of the appropriate size and shape can be clearly and rapidly demonstrated using electron microscopy. Analysis of electron micrographs reveals that the cell clusters have large macrophage like cells with multiple large membranes bound inclusions filled with virus particles. The virus particles sometimes form membrane-bound necklace-like arrangements [6, 48, 82].

Reverse Transcriptase PCR

Reverse transcription (RT) followed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is an important technique for amplification of RNA [120]. Reverse transcriptase PCR has been applied to amplify a portion of the coat protein gene (RNA2) of betanodavirus and is a powerful and sensitive method for detecting the infection [6, 10, 50, 90]. Till date, PCR is the main diagnostic test that is being used by most of laboratories. The sensitivity of this test depends on the strain of betanodavirus which is being targeted; hence specific primers are continuing to be developed [40]. Nested RT–PCR has been found to be 10–100 times more sensitive than the previously reported RT–PCR methods [29, 117]. The method can be applied to screen the virus from cultured and wild fish even when there are no clinical signs [43, 44]. Fish betanodavirus and its association with mass mortality of Asian seabass, (L. calcarifer) is detected by using RT–PCR (Fig. 3) [6, 97, 102], (Shetty et al. unpublished data). Real-time PCR also is sometimes used for rapid and sensitive detection of this virus. As nodavirus is very stable and can survive in seawater for a long time [36], it has been possible to detect and quantify the virus in seawater from rearing facilities for Atlantic halibut H.hippoglossus larvae [87]. Real-time PCR assay has been useful to study the transmission and development of this viral infection in juvenile [56].

Fig. 3.

RT–PCR detection of betanodavirus in Asian seabass (L. calcarifer) (Shetty et al. unpublished data) using T4NV-F2/R primer set [89]. M: 100 bp DNA ladder, Genei Bangalore, Lane 1 positive control. Lane 2 Negative control. Lane 3–6 positive samples

Another useful method is the nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA) [27] which is an isothermal method for nucleic acid amplification that is particularly suited to RNA targets [68]. The method amplifies a target-specific product through oligonucleotide primers and the co-ordinated activity of 3 enzymes: reverse transcriptase, RNase H, and T7 RNA polymerase. Real-time detection in NASBA is performed by applying molecular beacons, which are incorporated directly into amplification reactions [72]. The real-time NASBA procedure for the detection of betanodavirus has been developed and sensitivity of this assay was compared to a conventional single-tube RT–PCR assay [113].

Immunoassays

Immunological based assays which include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is the commonly used techniques for the detection of betanodavirus. The test involves the detection of specific nodavirus antibodies in blood and other body fluids. ELISA was one of the first immunological methods to be developed [2, 24] to detect SJNNV but was not very sensitive. It is commonly used since a large number and a variety of samples can be screened rapidly by these methods. Since the sensitivity of the technique may vary, it is more useful for epidemiological studies and outbreaks rather than for diagnostic purposes of detecting subclinical levels of infection. A convenient test to confirm the presence of betanodavirus infection is by immunofluorescent antibody testing using polyclonal and monoclonal antibody [82]. It is both rapid and economical and the polyclonal anti serum helps the detection of the full range of betanodavirus strains known. However, greater tissue quantities are required than for the ELISA test.

Cell Lines

For virus propagation, characterization and studies on infection mechanism, cell lines are important. The tissue culture method for isolates of fish betanodavirus was established in 1999 when the snakehead cell line (SSN-1) cell line derived from striped snakehead (Ophicephalus striatus) was developed to isolate and propagate betanodavirus from diseased seabass juveniles [35]. The virus from farmed Atlantic halibut H. hippoglossus is found to be stable without losing or changing the virulence after repeated cell culture [31]; however permissiveness is temperature dependent. SSN-1 cell line is useful for propagating and differentiating genotypic variants of piscine nodavirus [59]. The cell line has been cloned and since it shows stable cytopathic effect expression, it can be used for qualitative and quantitative analyses of piscine nodaviruses rather than the SSN-1 cell line [60]. Yet another cell line derived from the brain tissue of Barramundi L. calcarifer was developed which was used to study the mechanisms of NNV-persistent infection in vitro and in vivo [24]. A tropical marine fish cell line from the spleen of orange spotted grouper, Epinephelus coioides is developed and characterized which is found to be useful as a tool for transgenic and genetic manipulation studies [101]. India’s first marine fish cell line was developed and characterized from the kidney of Asian seabass (L. calcarifer) and consisted predominantly of epithelial-like cells [104]. A spleen cell line from Asian seabass (SISS) [95] and two other cell lines, SIMH and SIGE were derived from the heart of milkfish (Chanos chanos), a euryhaline teleost, and from the eye of grouper (E. coioides), respectively [96].

Epidemiology

Betanodavirus is an acute infectious disease of primarily finfish larvae and fry. To control the infections, it is important to understand the epidemiology and pathogenic mechanisms of the virus. Betanodavirus infection can be influenced by host factors such as age [1, 3], environmental factors such as water temperature [106, 115, 125] and other stress factors such as suboptimal feed, suboptimal water quality, crowding, transport and repeated spawning of broodstock [55, 64, 84, 115]. The virus can be transmitted both horizontally [15, 49, 71, 99] and vertically [2, 7, 14, 49, 83, 84, 92, 102, 119]. It can persist in the host for a long time sub-clinically and may cause severe mortality under extreme environmental conditions [105]. The horizontal transmission may occur from infected fish, feed, contaminated trash fish/carrier animals and contaminated water supply [18, 44, 47, 69, 87, 119]. The cannibalistic nature of fish such as Asian seabass and brown-marbled grouper fingerlings may also enhance the horizontal transmission of the virus [78]. Feeding of trash fish to cultured fish is also found to be a source of infection [47]. Some of the betanodavirus infected larval fish can survive and act as a carrier for the next generation [87]. Several authors studied the horizontal transmission of this virus during outbreaks and confirmed it by various experimental studies [3, 15, 88]. Arimoto et al. [2] was probably the first to demonstrate vertical transmission by detecting the virus in the fertilized eggs and also in 65 % of the striped jack brood fish by antibody-based ELISA technique. Vertical transmission has also been demonstrated in European seabass [26], Japanese flounder, barfin flounder [123], Atlantic halibut [51] and Asian seabass (L. calcarifer) [7].

Disease Control Strategies

During the last decade and continuing to the present, betanodavirus has been one of the major limiting factors in the culture of fish all over the world. In intensive aquaculture, where single or multiple species are reared at high densities, infectious disease agents are easily transmitted between individuals. First step to control the betanodavirus infection would be the development of location specific better management practices (BMPs) which are scientific management procedures. Significant benefits could be achieved in farming systems by adopting these BMPs. The BMP approach includes the use of specific-pathogen-free broodstock, quality feeding, improved husbandry practices, good sanitation, use of probiotics and immunostimulants etc.

Since the epidemiological knowledge of betanodavirus disease is limited, it important to follow combination of measures to reduce the risk factors. Betanodavirus is shed from broodstock during spawning and probably adheres to the egg surface thus infecting larvae when hatching takes place. The stress that a seropositive broodstock encounters needs to be addressed for reducing the shedding. It would be ideal to reduce the stocking density. To prevent the vertical transmission of the virus to the offspring, the eggs can be washed in ozonated water for inactivating the virus which may be found on the surface. Horizontal transmission can be reduced by avoiding extensive mixing of batches of larvae/juveniles [105]. Other methods that can be considered include the ozonation of influent water, maintaining quarantine of ill and introduced fish, maintaining biosecurity between different parts of the facility and disinfecting tanks between batches [83].

It has been observed that betanodavirus strains tend to be geographically related rather than to the fish species from which it has been isolated [40]. To ensure that the fish are as healthy as possible, a useful and practical approach would be vaccination of fish and boosting their immune system. Various types of vaccines have been developed such as formalin-inactivated vaccine, subunit vaccine with recombinant coat protein of betanodavirus and nodavirus-like particle vaccine [58, 74, 111, 116, 118, 121, 124]. Vaccination trials have shown protection efficacy against betanodavirus infection. For example, recombinant partial capsid protein of SJNNV [58] and AHNV [111] vaccinated turbot and Atlantic halibut fish are protected significantly against nodavirus challenge. Additionally, use of DNA vaccine based on the gene encoding for G protein of VHSV offers high but short term protection against the nodavirus infection [109]. Vaccination against betanodavirus of larvae or juvenile fish is a difficult process because the immune system of fish is not well developed at this stage and the most effective vaccination method which is delivering the vaccine candidate by injection is impractical due to small size of the fish. Brood fish, on the other hand can be immunized before spawning to minimize the risk of vertical transmission. Oral vaccination can be standardized to prevent disease occurring at the early larval stage. For example, Artemia-encapsulated recombinant Escherichia coli expressing the NNV capsid protein gene delivered through oral route showed a certain degree of protection after challenge with NNV (relative percentage survival up to 69.5 %) [73]. The protection efficacy can be improved by manipulating the expression in the host. Antigen expressed in Vibrio anguillarum, a common marine bacterium with immune-stimulatory capability followed by oral vaccination can enhance the efficacy in a shorter incubation period and can reduce the risk of NNV infection at early stage [17]. Some natural products from plants are found to be effective against viruses and can be used as antiviral drugs [57]. Many antiviral drugs have been synthesized in the recent past and researches on development of potent antiviral agents are continuing to address the issue of viral diseases [32, 70]. Several antiviral compounds, like tilapia hepcidin 1-5(TH1-5), cyclic shrimp anti-lipopolysaccharide factor [20], furan-2yl-acetate [114], gymnemagenol [67] and Dasyscyphin C (C28H40O8) [70] are also reported to be active against fish betanodavirus.

Concluding Remarks

Betanodavirus infection in freshwater and in marine fish species is a serious issue. The past few decades have witnessed a lot of interest in addressing disease problems due to nodavirus and many studies on the various aspects of this virus have been carried out on its occurrence, distribution, genomics, pathogenesis, pathogenicity and protection strategies. Several rapid and sensitive diagnostics have been developed to identify the risk of presence of the virus in brood fish and to enable stocking of virus free larvae and juveniles. However, further studies are required to identify infected broodstock and development of a commercial vaccine that would be useful to the industry. Research on the molecular characteristics of the virus, interactions between host and the pathogen, route of transmission in aquaculture and survival of the virus in the natural environment is in progress. Studies are required to analyze and compare the betanodavirus types as they continue to be reported from various regions. To reduce the severe economic losses to the aquaculture industry, the control of disease is very important. A combination of good management practices together with vaccination of adult and/or young fry would be ideal. Discovery of new generation recombinant vaccines with appropriate practical delivery method such as the oral route using nanoparticles and boosting the immunogenicity of antigen with adjuvant or any immune component would be the ideal means of controlling the disease.

Acknowledgments

The funding through the COE-programme support to Aquaculture and Marine Biotechnology by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Aranguren R, Tafalla C, Novoa B, Figueras A. Experimental transmission of encephalopathy and retinopathy induced by nodavirus to sea bream, Sparus aurata L., using different infection models. J Fish Dis. 2002;25:317–324. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arimoto M, Mushiake K, Mizuta Y, Nakai T, Muroga K, Furusawa I. Detection of striped jack nervous necrosis virus (SJNNV) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Fish Pathol. 1992;27:191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arimoto M, Mori K, Nakai T, Muroga K, Furusawa I. Pathogenicity of the causative agent of viral necrosis disease in striped jack, Pseudocaranx dentex (Block & Schneider) J Fish Dis. 1993;16:461–469. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aspehaug V, Devold M, Nylund A. The phylogenetic relationship of nervous necrosis virus from halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol. 1999;19:196–202. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Athanassopoulou F, Billinis C, Prapas T. Important disease conditions of newly cultured species in intensive freshwater farms in Greece: first incidence of nodavirus infection in Acipenser sp. Dis Aquat Organ. 2004;60:247–252. doi: 10.3354/dao060247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azad IS, Shekar MS, Thirunavukkarasu AR, Poornima M, Kailasan M, Rajan JJS, Ali SA, Abraham M, Ravichandran P. Nodavirus infection causes mortalities in hatchery produced larvae of Lates calcarifer: first report from India. Dis Aquat Organ. 2005;63:113–118. doi: 10.3354/dao063113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azad IS, Shekhar MS, Thirunavukkarasu AR, Jithendran KP. Viral nerve necrosis in hatchery-produced fry of Asian seabass Lates calcarifer: sequential microscopic analysis of histopathology. Dis Aquat Organ. 2006;73:123–130. doi: 10.3354/dao073123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ball LA, Hendry DA, Johnson JE, Rueckert RR, Scotti PD. Family Nodaviridae. In: Regenmortel MHV, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Carstens EB, Estes MK, Lemon SM, Maniloff J, Mayo MA, McGeoch DJ, Pringle CR, Wickner RB, editors. Virus taxonomy Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego: Academic; 2000. pp. 747–755. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeck GW, Gomez DK, Oh KS, Kim JH, Choresca CH, Jr, Park SC. Detection of piscine nodaviruses from apparently healthy wild marine fish in Korea. Bull Eur Assoc Fish Pathol. 2007;27:116–122. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barke DE, MacKinnon AM, Boston L, Burt MD, Cone DK, Speare DJ, Griffiths S, Cook M, Ritchie R, Olivier G. First report of piscine nodavirus infecting wild winter flounder Pleuronectes americanus in Passamaquoddy Bay, New Brunswick. Canada Dis Aquat Organ. 2002;49:99–105. doi: 10.3354/dao049099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellance R, Gallet de Saint-Aurin D. L’encephalite virale de loup de mer. Caraibes Med. 1998;2:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bloch B, Gravningen K, Larsen JL. Encephalomyelitis among turbot associated with a picornavirus-like agent. Dis Aquat Organ. 1991;10:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuil G, Bonami JR, Pepin JF, Pichot Y. Viral infection (picorna-like virus) associated with mass mortalities in hatchery-reared sea-bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) larvae and juveniles. Aquaculture. 1991;97:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breuil B, Pepin JFP, Boscher S, Thiery R. Experimental vertical transmission of nodavirus from broodfish to eggs and larvae of the sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.) J Fish Dis. 2002;25:697–702. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castric J, Thiery R, Jeffroy J, de Kinkelin P, Raymond JC. Sea bass Sparus aurata, an asymptomatic contagious fish host for nodavirus. Dis Aquat Organ. 2001;47:33–38. doi: 10.3354/dao047033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cha SJ, Do JW, Lee NS, An EJ, Kim YC, Kim JW, Park JW. Phylogenetic analysis of betanodaviruses isolated from cultured fish in Korea. Dis Aquat Organ. 2007;77:181–189. doi: 10.3354/dao01840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Shih C, Liu H, Wu C, Lin C, Wang H, Chen T, Yang H, Lin J. An oral nervous necrosis virus vaccine using Vibrio anguillarum as an expression host provides early protection. Aquaculture. 2011;321:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherif N, Thiery R, Castric J, Biacchesi S, Bremont M, Thabti F, Limem L, Hammami S. Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy of Dicentrarchus labrax and Sparus aurata farmed in Tunisia. Vet Res Commun. 2009;33:345–353. doi: 10.1007/s11259-008-9182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherif N, Gagne N, Groman D, Kibenge F, Iwamoto T, Yason C, Hammami S. Complete sequencing of Tunisian redspotted grouper nervous necrosis virus betanodavirus capsid gene and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene. J Fish Dis. 2010;33:231–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2009.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chia TJ, Wu YC, Chen JY, Chi SC. Antiviral activities of AMPs against NNV in fish cells, and elucidated their anti-NNV mechanisms in vitro. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010;28:434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chi SC, Lo CF, Kou GH, Chang PS, Peng SE, Chen SN. Mass mortalities associated with viral nervous necrosis (VNN) disease in two species of hatchery-reared grouper, Epinephelus fuscogutatus and Epinephelus akaara (Temminck & Schlegel) J Fish Dis. 1997;20:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chi SC, Hu WW, Lo BJ. Establishment and characterization of a continuous cell line (GF-1) derived from grouper, Epinephelus coicoides (Hamilton): a cell line susceptible to grouper nervous necrosis virus (GNNV) J Fish Dis. 1999;22:173–182. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chi SC, Shieh JR, Lin SJ. Genetic and antigenic analysis of betanodaviruses isolated from aquatic organisms in Taiwan. Dis Aquat Organ. 2003;55:221–228. doi: 10.3354/dao055221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chi SC, Wu YC, Cheng TM. Persistent infection of betanodavirus in a novel cell line derived from the brain tissue of barramundi Lates calcarifer. Dis Aquat Organ. 2005;65:91–98. doi: 10.3354/dao065091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chua FHC, Loo JJ, Wee JY. Mass mortality in juvenile greasy grouper, Epinephelus tauvina, associated with vacuolating encephalopathy and retinopathy. Dis Asian Aquac. 1995;11:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comps M, Trindade M, Delsert CL. Investigation of encephalitis viruses (FEV) expression in marine fishes using DIG-labelled probes. Aquaculture. 1996;143:113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Compton J. Nucleic acid sequence based amplification. Nature. 1991;350:91–92. doi: 10.1038/350091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crane M, Hyatt A. Viruses of fish: an overview of significant pathogens. Viruses. 2011;3:2025–2046. doi: 10.3390/v3112025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalla Valle L, Zanella L, Patarnello P, Paolucci L, Belvedere P, Colombo L. Development of a sensitive diagnostic assay for fish nervous necrosis virus based on RT–PCR plus nested PCR. J Fish Dis. 2000;23:321–328. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danayadol Y, Direkbusarakom S, Supamattaya K. Viral nervous necrosis in brownspotted grouper, Epinephelus malabaricus, cultured in Thailand. In: Shariff M, Arthur JR, Subasinghe RP, editors. Diseases in Asian aquaculture II. Manila: Asian Fisheries Society; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dannevig BH, Nilsen R, Modahl I, Jankowska M, Taksdal T, Press CM. Isolation in cell culture of nodavirus from farmed Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus in Norway. Dis Aquat Organ. 2000;43:183–189. doi: 10.3354/dao043183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Clercq E. Antiviral agents: characteristic activity spectrum depending on the molecular target with which they interact. Adv Virus Res. 1993;42:1–55. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.FAO yearbook 2008. Fishery and aquaculture statistics. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nations; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fenner BJ, Thiagarajan R, Chua HK, Kwang J. Betanodavirus B2 is a RNA interference antagonist that facilitates intracellular viral RNA accumulation. J Virol. 2006;80:85–94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.85-94.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frerichs GN, Rodger HGD, Peric Z. Cell culture isolation of piscine neuropathy nodavirus from juvenile sea bass. Dicentrarchus labrax. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2067–2071. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frerichs GN, Tweedie A, Starkey WG, Richards RH. Temperature, pH and electrolyte sensitivity, and heat, UV and disinfectant inactivation of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) neuropathy nodavirus. Aquaculture. 2000;185:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukuda Y, Nguyen HD, Furuhashi M, Nakai T. Mass mortality of cultured sevenband grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus, associated with viral nervous necrosis. Fish Pathol. 1996;31:165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furusawa R, Okinaka Y, Nakai T. Betanodavirus infection in the freshwater model fish medaka (Oryzias latipes) J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2333–2339. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81761-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furusawa R, Okinaka Y, Uematsu K, Nakai T. Screening of freshwater fish species for their susceptibility to a betanodavirus. Dis Aquat Organ. 2007;77:119–125. doi: 10.3354/dao01841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gagne N, Johnson SC, Cook-Versloot M, MacKinnon AM, Olivier G. Molecular detection and characterization of nodavirus in several marine fish species from the northeastern Atlantic. Dis Aquat Organ. 2004;62:181–189. doi: 10.3354/dao062181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glazebrook JS, Campbell RSF. Diseases of barramundi (Lates calcarifer) in Australia: a review. In: Copland JW, Grey DI, editors. Management of wild and cultured Sea bass/Barramundi Lates calcarifer. Canberra: ACIAR; 1987. pp. 204–206. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glazebrook JS, Heasman MP, de Beer SW. Picorna-like viral particles associated with mass mortalities in larval barramundi, Lates calcarifer (Bloch) J Fish Dis. 1990;13:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomez DK, Sato J, Mushiake K, Isshiki T, Okinaka Y, Nakai T. PCR-based detection of betanodaviruses from cultured and wild marine fish with no clinical signs. J Fish Dis. 2004;27:603–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2004.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez DK, Baeck GW, Kim JH, Choresca CH, Jr, Park SC. Molecular detection of betanodavirus in wild marine fish populations in Korea. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20:38–44. doi: 10.1177/104063870802000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez DK, Baeck GW, Kim JH, Choresca CH, Jr, Park SC. Genetic analysis of betanodaviruses in subclinically infected aquarium fish and invertebrates. Curr Microbiol. 2008;56:499–504. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomez DK, Matsuoka S, Mori K, Okinaka Y, Park SC, Nakai T. Genetic analysis and pathogenicity of betanodavirus isolated from wild redspotted grouper Epinephelus akaara with clinical signs. Arch Virol. 2009;154:343–346. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomez DK, Mori K, Okinaka Y, Nakai T, Park SC. Trash fish can be a source of betanodaviruses for cultured marine fish. Aquaculture. 2010;302:158–163. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grotmol S, Totland GK, Kryvi H. Detection of a nodavirus-like agent in heart tissue from reared Atlantic salmon Salmo salar suffering from cardiac myopathy syndrome (CMS) Dis Aquat Organ. 1997;29:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grotmol S, Bergh O, Totland GK. Transmission of viral encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER) to yolk-sac larvae of the Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus: occurrence of nodavirus in various organs and a possible route of infection. Dis Aquat Organ. 1999;36:95–106. doi: 10.3354/dao036095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grotmol S, Nerland AH, Beering E, Totland GK, Nishizawa T. Characterisation of the capsid protein gene from a nodavirus strain affecting the Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus and design of an optimal RT–PCR (RTPCR) detection assay. Dis Aquat Organ. 2000;39:79–88. doi: 10.3354/dao039079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grotmol S, Totland GK. Surface disinfection of Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus eggs with ozonated sea-water inactivates nodavirus and increases survival of the larvae. Dis Aquat Organ. 2000;39:89–96. doi: 10.3354/dao039089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hasoon MF, Daud HM, Arshad SS, Bejo MH. Betanodavirus experimental infection in freshwater ornamental guppies: diagnostic histopathology and RT–PCR. J Adv Med Res. 2011;1:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hegde A, Teh HC, Lam TJ, Sin YM. Nodavirus infection in freshwater ornamental fish, guppy Poicelia reticulata—comparative characterization and pathogenicity studies. Arch Virol. 2003;148:575–586. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hick P, Tweedie A, Whittington R. Preparation of fish tissues for optimal detection of betanodavirus. Aquaculture. 2010;310:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hick P, Schipp G, Bosmans J, Humphrey J, Whittington R. Recurrent outbreaks of viral nervous necrosis in intensively cultured barramundi (Lates calcarifer) due to horizontal transmission of betanodavirus and recommendations for disease control. Aquaculture. 2011;319:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hodneland K, Garcia R, Balbuena JA, Zarza C, Fouz B. Real-time RT–PCR detection of betanodavirus in naturally and experimentally infected fish from Spain. J Fish Dis. 2011;34:189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2010.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hudson JB. Antiviral compounds from plants. Florida: CRC; 1990. p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Husgar S, Grotmol S, Hjeltnes BK, Rodseth OM, Biering E. Immune response to a recombinant capsid protein of striped jack nervous necrosis virus (SJNNV) in turbot Scophthalmus maximus and Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus, and evaluation of a vaccine against SJNNV. Dis Aquat Organ. 2001;45:33–44. doi: 10.3354/dao045033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iwamoto T, Mori K, Arimoto M, Nakai T. High permissivity of the fish cell line SSN-1 for piscine nodaviruses. Dis Aquat Organ. 1999;39:37–47. doi: 10.3354/dao039037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iwamoto T, Nakai T, Mori K, Arimoto M, Furusawa I. Cloning of the fish cell line SSN-1 for piscine nodaviruses. Dis Aquat Organ. 2000;43:81–89. doi: 10.3354/dao043081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iwamoto T, Mise K, Takeda A, Okinaka Y, Mori KI, Arimoto M, Nakai T. Characterization of striped jack nervous necrosis virus sub genomic RNA3 and biological activities of its encoded protein B2. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2807–2816. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jithendran KP, Shekhar MS, Kannappan S, Azad IS. Nodavirus infection in freshwater ornamental fishes in India: diagnostic histopathology and nested RT–PCR. Asian Fish Soc. 2011;24:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johansen R, Amundsen M, Dannevig BH, Sommer AI. Acute and persistent experimental nodavirus infection in spotted wolffish Anarhichas minor. Dis Aquat Organ. 2003;57:35–41. doi: 10.3354/dao057035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johansen R, Sommerset I, Tørud B, Korsnes K, Hjortaas MJ, Nilsen F, Nerland AH, Dannevig BH. Characterization of nodavirus and viral encephalopathy and retinopathy in farmed turbot, Scophthalmus maximus (L.) J Fish Dis. 2004;27:591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2004.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johnson SC, Sperker SA, Leggiadro CT, Groman DB, Griffiths SG, Ritchie RJ, Cook MD, Cusack RR. Identification and characterization of a piscine neuropathy and nodavirus from juvenile Atlantic cod from the Atlantic coast of North America. J Aquat Anim Health. 2002;14:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jung SJ, Oh MJ. Iridovirus-like infection associated with high mortalities of striped beakperch, Oplegnathus fasciatus, Southern coastal areas of Korean peninsula. J Fish Dis. 2000;23:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khanna VG, Kannabiran K, Sarath Babu V, Sahul Hammed AS. Inhibition of fish nodavirus gymnemagenol extracted from Gymnema sylvestre. J Ocean Univ China. 2011;10:402–408. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kievits T, van Gemen B, van Strijp D, Schukkink R, Dircks M, Adriaanse H, Malek L, Sooknanan R, Lens P. NASBA isothermal enzymatic in vitro nucleic acids amplification optimised for the diagnosis of HIV-1 infection. J Virol Methods. 1991;35:273–286. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(91)90069-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kokawa Y, Takami I, Nishizawa T, Yoshimizu M. A mixed infection in sevenband grouper Epinephelus septemfasciatus affected with viral nervous necrosis (VNN) Aquaculture. 2008;284:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krishnan K, Gopiesh Khanna V, Sahul Hameed AS. Antiviral activity of dasyscyphin C extracted from Eclipta prostrataagainst fish nodavirus. J Antivir Antiretrovir. 2010;2:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Le Breton A, Grisez L, Sweetman J, Ollevier F. Viral nervous necrosis (VNN) associated with mass mortalities in cage- reared sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax (L.) J Fish Dis. 1997;20:1145–1151. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leone GH, van Schijndel H, van Gemen B, Kramer FR, Schoen CD. Molecular beacon probes combined with amplification by NASBA enables homogenous real time detection of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2150–2155. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin C, Lin JH, Chen M, Yang H. An oral nervous necrosis virus vaccine that induces protective immunity in larvae of grouper (Epinephelus coioides) Aquaculture. 2007;268:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu W, Hsu CH, Chang CY, Chen HH, Lin CS. Immune response against grouper nervous necrosis virus by vaccination of virus-like particles. Vaccine. 2006;24:6282–6287. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu H, Teng Y, Zheng X, Wu Y, Xie X, He J, Ye Y, Wu Z. Complete sequence of a viral nervous necrosis virus (NNV) isolated from red-spotted grouper (Epinephelus akaara) in China. Arch Virol. 2012;157:777–782. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu MW, Chao YM, Guo TC, Santi N, Evensen O, Kasani SK, Hong JR, Wu JL. The interferon response is involved in nervous necrosis virus acute and persistent infection in zebrafish infection model. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:1146–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maeno Y, Pena LD, Lacierda ERC. Mass mortalities associated with viral nervous necrosis in hatchery-reared seabass Lates calcarifer in the Philippines. Jpn Agr Res Q. 2004;38:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manin BO, Ransangan J. Experimental evidence of horizontal transmission of betanodavirus in hatchery-produced Asian seabass, Lates calcarifer and brown-marbled grouper, Epinephelus fuscoguttatus fingerling. Aquaculture. 2011;321:157–165. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mezeth KB, Patel S, Henriksen H, Szilvay AM, Nerland AH. B2 protein from betanodavirus is expressed in recently infected but not in chronically infected fish. Dis Aquat Organ. 2009;83:97–103. doi: 10.3354/dao02015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mori K, Nakai T, Nagahara M, Muroga K, Mukuchi T, Kanno T. A viral disease in hatchery-reared larvae and juveniles of redspotted grouper. Fish Pathol. 1991;26:209–210. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mori K, Nakai T, Muroga K, Arimoto M, Mushiake K, Furusawa I. Properties of a new virus belonging to Nodaviridae found in larval striped jack (Pseudocaranx dentex) with nervous necrosis. Virology. 1992;187:368–371. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90329-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Munday BL, Nakai T. Nodaviruses as pathogens in larval and juvenile marine finfish. World J Microb Biot. 1997;13:375–381. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Munday BL, Kwang J, Moody N. Betanodavirus infections of teleost fish: a review. J Fish Dis. 2002;25:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mushiake K, Nishizawa T, Nakai T, Furusawa I, Muroga K. Control of VNN in striped jack: selection of spawners based on the detection of SJNNV gene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) J Fish Pathol. 1994;29:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakai T, Mori K, Nishizawa T, Muroga K. Viral nervous necrosis of larval and juvenile marine fish. In: Proceedings of the international symposium on biotechnology applications in aquaculture, vol. 10. Manila: Asian Fisheries Society; 1995. p. 147–52.

- 86.Nakai T, Mori K, Sugaya T, Nishioka T, Mushiake K, Yamashita H. Current knowledge on viral nervous necrosis (VNN) and its causative betanodaviruses. Isr J Aquacult-Bamid. 2009;61:198–207. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nerland AH, Skaar C, Eriksen TB, Bleie H. Detection of nodavirus in seawater from rearing facilities for Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus larvae. Dis Aquat Organ. 2007;73:201–205. doi: 10.3354/dao073201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nguyen HD, Nakai T, Muroga K. Progression of striped jack nervous necrosis virus (SJNNV) infection in naturally and experimentally infected striped jack Pseudocaranxdentex larvae. Dis Aquat Organ. 1996;24:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nishizawa T, Mori K, Nakai T, Furusawa I, Muroga K. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of RNA of striped jack nervous necrosis virus (SJNNV) Dis Aquat Organ. 1994;18:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nishizawa T, Mori K, Furuhashi M, Nakai T, Furusawa I, Muroga K. Comparison of the coat protein genes of five fish nodaviruses, the causative agents of viral nervous necrosis in marine fish. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1563–1569. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-7-1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nishizawa T, Furuhashi M, Nagai T, Nakai T, Muroga K. Genomic classification of fish nodaviruses by molecular phylogenetic analysis of the coat protein gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1633–1636. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1633-1636.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oh MJ, Jung SJ, Kim SR, Rajendran KV, Kim YJ, Choi TJ, Kim HR, Kim JD. A fish nodavirus associated with mass mortality in hatchery-reared red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus. Aquaculture. 2002;211:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Manual of diagnostic tests for aquatic animals. Paris: OIE; 2003. Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy; pp. 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Panzarin V, Fusaro A, Monne I, Cappellozza E, Patarnello P, Bovo G, Capua I, Holmes EC, Cattoli G. Molecular epidemiology and evolutionary dynamics of betanodavirus in southern Europe. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Parameswaran V, Shukla R, Bhonde RR. Sahul Hameed AS. Splenic cell line from sea bass, Lates calcarifer: establishment and characterization. Aquaculture. 2006;261:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Parameswaran V, Ishaq Ahmed VP, Shukla RR, Bhonde R, Sahul Hameed AS. Development and characterization of two new cell lines from milkfish (Chanos chanos) and grouper (Epinephelus coioides) for virus isolation. Mar Biotechnol. 2007;9:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s10126-006-6110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parameswaran V, Kumar SR, Hameed Ahmed AS. A fish nodavirus associated with mass mortality in hatchery—reared Asian sea bass, Lates calcarifer. Aquaculture. 2008;275:366–369. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Patel S, Korsnes K, Bergh O, Vik-Mo F, Pedersen J, Nerland AH. Nodavirus in farmed Atlantic cod Gadus morhua in Norway. Dis Aquat Organ. 2007;77:169–173. doi: 10.3354/dao01842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peducasse S, Castric J, Thiery R, Jeffroy J, Le Ven A, Baudin Laurencin F. Comparative study of viral encephalopathy and retinopathy in juvenile sea bass Dicentrarchuslabrax infected in different ways. Dis Aquat Organ. 1999;36:11–20. doi: 10.3354/dao036011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pirarat N, Katagiri T, Maita M, Nakai T, Endo M. Viral encephalopathy and retinopathy in hatchery-reared juvenile thread-sail filefish (Stephanolepis cirrhifer) Aquaculture. 2009;288:349–352. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Qin QW, Wu TH, Jia TL, Hegde A, Zhang RQ. Development and characterization of a new tropical marine fish cell line from grouper, Epinephelus coioides susceptible to iridovirus and nodavirus. J Virol Methods. 2006;131:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ransangan J, Manin BO. Mass mortality of hatchery- produced larvae of Asian sea bass, Lates calcarifer (Bloch), associated with nervous necrosis in Sabah, Malaysia. Vet Microbiol. 2010;145:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ransangan J, Manin BO, Abdullah A, Roli Z, Sharudin EF. Betanodavirus infection in golden pompano, Trachinotus blochii, fingerlings cultured in deep-sea cage culture facility in Langkawi, Malaysia. Aquaculture. 2011;315:327–334. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sahul Hameed AS, Parameswaran V, Shukla R, Bright Singh IS, Thirunavukkarasu AR, Bhonde RR. Establishment and characterization of India’s first marine fish cell line (SISK) from the kidney of sea bass (Lates calcarifer) Aquaculture. 2006;257:92–103. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Samuelsen OB, Nerland AH, Jorgensen T, Schroder MB, Svasand T, Bergh O. Viral and bacterial diseases of Atlantic cod Gadus morhua, their prophylaxis and treatment: a review. Dis Aquat Organ. 2006;71:239–254. doi: 10.3354/dao071239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Skliris GP, Richard RH. Induction of nodavirus disease in sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax, using different infection models. Virus Res. 1999;63:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Skliris GP, Krondiris JV, Sideris DC, Shinn AP, Starkey WG, Richard RH. Phylogenetic and antigenic characterization of new fish nodavirus isolates from Urope and Asia. Virus Res. 2001;75:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(01)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sohn SG, Park MA, Oh MJ, Chun SK. A fish nodavirus isolated from cultured sevenband grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus. J Fish Pathol. 1998;11:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sommerset I, Lorenzen E, Lorenzen N, Bleie H, Nerland AH. A DNA vaccine directed against a rainbow trout rhabdovirus induces early protection against a nodavirus challenge in turbot. Vaccine. 2003;21:4661–4667. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sommerset I, Nerland AH. Complete sequence of RNA1 and subgenomic RNA3 of Atlantic halibut nodavirus (AHNV) Dis Aquat Organ. 2004;58:117–125. doi: 10.3354/dao058117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sommerset I, Skern R, Biering E, Bleie H, Fiksdal IU, Grove S, Nerland AH. Protection against Atlantic halibut nodavirus in turbot is induced by recombinant capsid protein vaccination but not following DNA vaccination. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2005;18:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Starkey WG, Ireland JH, Muir KF, Jenkins ME, Roy WJ, Richards RH, Ferguson HW. Nodavirus infection in Atlantic cod and Dover sole in the UK. Vet Rec. 2001;149:179–181. doi: 10.1136/vr.149.6.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Starkey WG, Millar RM, Jenkins ME, Ireland JH, Muir KF, Richards RH. Detection of piscine nodaviruses by real-time nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA) Dis Aquat Organ. 2004;59:93–100. doi: 10.3354/dao059093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Suthindhiran K, Sarath Babu V, Kannabiran K, Ishaq Ahmed VP, Sahul Hameed AS. Anti-fish nodaviral activity of furan-2-yl acetate extracted from marine Streptomyces spp. Nat Prod Res. 2011;25:834–843. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2010.530599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tanaka S, Aoki H, Nakai T. Pathogenicity of the nodavirus detected from diseased sevenband grouper Epinephelus septemfasciatus. Fish Pathol. 1998;33:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tanaka S, Mori K, Arimoto M, Iwamoto T, Nakai T. Protective immunity of sevenband grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus Thunberg, against experimental viral nervous necrosis. J Fish Dis. 2001;24:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Thiery R, Raymond JC, Castric J. Natural outbreak of viral encephalopathy and retinopathy in juvenile sea bass, Dicentrarrchus labrax: study by nested reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Virus Res. 1999;63:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Thiery R, Cozien J, Cabon J, Lamour F, Baud M, Schneemann A. Induction of a protective immune response against viral nervous necrosis in the European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax by using betanodavirus virus-like particle. J Virol. 2006;80:10201–10207. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01098-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Watanabe K, Nishizawa T, Yoshimizu M. Selection of brood stock candidates of barfin flounder using an ELISA system with recombinant protein of barfin flounder nervous necrosis virus. Dis Aquat Organ. 2000;41:219–223. doi: 10.3354/dao041219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xu LZ, Larzul D. The polymerase chain reaction: basic methodology and applications. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;14:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(91)90001-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yamashita Y, Fujita Y, Kawakami H, Nakai T. The efficacy of inactivated virus vaccine against viral nervous necrosis (VNN) Fish Pathol. 2005;40:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yoshikoshi K, Inoue K. Viral nervous necrosis in hatchery-reared larvae and juveniles of Japanese parrotfish, Oplegnathus fasciatus (Temminck & Schlegel) J Fish Dis. 1990;13:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yoshimizu M, Suzuki K, Nishizawa T, Winton JR, Ezura Y. Antibody screening for the identification of nervous necrosis in flounder broodstock. In: Proceedings NRIA international workshop on new approaches to viral diseases of aquatic animals. Kyoto: USGS; 1997. p. 124–30.

- 124.Yuasa K, Koesharyani I, Roza D, Mori K, Katata M, Nakai T. Immune response of humpback grouper, Cromileptes altivelis (Valenciennes) injected with the recombinant coat protein of betanodavirus. J Fish Dis. 2002;25:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Yuasa K, Koesharyani I, Mahardika K. Effect of high water temperature on betanodavirus infection of fingerling humpback grouper Cromileptes altivelis. Fish Pathol. 2007;42:219–221. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zafran HT, Koesharyani I, Yuasa K, Hatai K. Indonesian hatchery reared sea bass larvae (Lates calcarifer), associated with viral nervous necrosis (VNN) Indonesian Fish Res J. 1998;4:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zafran KI, Johnny F, Yuasa K, Harada T, Hatai K. Viral nervous necrosis in humpback grouper Cromileptes altivelis larvae and juveniles in Indonesia. Fish Pathol. 2000;35:95–96. [Google Scholar]