Abstract

Multicomponent ssDNA plant viruses were discovered during 1990s. They are associated with bunchy top, yellowing and dwarfing diseases of several economic plants under family Musaceae, Leguminosae and Zingiberaceae. In the current plant virus taxonomy, these viruses are classified under the family Nanoviridae containing two genera, Nanovirus and Babuvirus. The family Nanoviridae was created with five members in 2005 and by 2010, it has expanded with four additional members. The viruses are distributed in the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, Australia, Europe and Africa. The viruses are not sap or seed transmissible and are naturally transmitted by aphid vector in a persistent manner. The genome is consisted of several circular ssDNAs of about 1 kb each. Up to 12 DNA components have been isolated from the diseased plant. The major viral proteins encoded by these components are replication initiator protein (Rep), coat protein, cell-cycle link protein, movement protein and a nuclear shuttle protein. Each ssDNA contains a single gene and a noncoding region with a stable stem and loop structure. Several Rep encoding components have been reported from each virus, only one of them designated as master Rep has ability to control replication of the other genomic components. Infectivity of the genomic DNAs was demonstrated only for two nanoviruses, Faba bean necrotic yellows virus and Faba bean necrotic stunt virus (FBNSV). A group of eight ssDNA components of FBNSV were necessary for producing disease and biologically active progeny viruses. So far, infectivity of genomic components of Babuvirus has not been demonstrated.

Keywords: Nanovirus, Babuvirus, ssDNA virus, BBTV, ABTV, CBTV, SCSV, FBNYV, FBNSV, PNYDV, MDV, CFDV

Introduction

There were several historical plant diseases for which the causal virus was a puzzle for a long time (Table 1). Bunchy top of banana [51] and abaca [68], stunt or dwarf of subterranean clover [28] and milk vetch [62], and foorkey of large cardamom [66] are examples of such diseases, which were identified as of viral origin largely based on symptoms and transmission by aphid. Involvement of specific viruses with the diseased plants could not be easily established as recognizable virus-like structure was not readily seen in electron microscope. The causal virus of some of these diseases like bunchy top of banana and dwarfing/stunting of milk vetch and subterranean clover was misunderstood as luteovirus [63, 71, 81]. During late 1980s and early 1990s, when virus purification was successful from several of these diseases, association of smallest isometric virus of 17–20 nm was evident [13, 40, 44, 73, 103]. Subsequently, during 1993–1995, genome sequencing and molecular characterisation revealed that these viruses contained multiple components of single stranded circular DNA (ssDNA) each about 1.0 kb in size. Both the virion and genome size being smallest of all the known plant viruses and having no significant sequence similarities with any other plant viruses, they were classified under the genus Nanovirus (nano = small), a new class of plant viruses [78]. Unlike other plant viruses, where viral genes are generally clustered together in one or a few genome components; in the nanoviruses, each gene is located in an independent ssDNA component. As a result, genomic information is distributed in at least 6–8 circular ssDNA components [98]. Nanovirus having some similarities in genome structure was thought to be a relative of geminivirus that was discovered during 1980s and was known to be the only ssDNA virus infecting plants [15]. Geminivirus, however, having unique twin-isometric virion of 18 × 30 nm and mono or bipartite genome component, was different from nanoviruses. Vertebrate-infecting ssDNA viruses, circoviruses also have similarities with nanoviruses. It appears that circoviruses have evolved diverging from nanoviruses through host-switching event [24].

Table 1.

Historical milestones of advances in multicomponent ssDNA viruses infecting plants

| Crop | Disease | Country | Milestone year | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease record | Virus observation | Genome sequence | Infectivity of cloned DNAs | ||||

| Banana | Bunchy top | Fiji | 1879 | 1990 | 1993 | – | [53, 103, 32] |

| Abaca | Bunchy top | Philippines | 1915 | – | 2008 | – | [68, 87] |

| Large cardamom | Foorkey | India | 1935 | 2004 | 2004 | – | [66, 60] |

| Milk vetch | Dwarf | Japan | 1953 | 1992 | 1998 | – | [62, 40, 86] |

| Subterranean clover | Stunt | Australia | 1956 | 1988 | 1995 | – | [28, 13, 8] |

| Coconut | Foliar decay | Vanuatu | 1979 | 1989 | 1990 | – | [18, 73, 82] |

| Faba bean | Necrotic yellows | Syria | 1988 | 1993 | 1995 | 2006 | [56, 44, 45, 95] |

| Faba bean | Necrotic stunt | Ethiopia | 1999 | – | 2009 | 2009 | [23, 25] |

| Pea | Necrotic yellow dwarf | Germany | 2009 | – | 2010 | – | [26] |

In the recent years, there is a considerable progress in our understanding of multicomponent ssDNA plant viruses. A large pool of genome sequence data has been accumulated, new members are discovered and taxonomy has been re-structured. Genome organization and protein function of nanoviruses have been reviewed in 2004 [27]. The present review describes the advances on both Nanovirus and Babuvirus and the diseases caused by them.

Taxonomic Structure

In the 7th report of International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), multicomponent ssDNA small plant viruses were classified as genus Nanovirus [78]. The work on genome analysis revealed that the legume-infecting ssDNA viruses have closer resemblance among themselves, but they differ substantially from those infecting banana. Because of the biological and molecular distinction, the classification of nanoviruses was revised in the 8th report of ICTV and the family, Nanoviridae was created with two genera, Nanovirus and Babuvirus [98]. The genus Nanovirus, included three species, Faba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV), Milk vetch dwarf virus (MDV) and Subterranean clover stunt virus (SCSV). Recently, two new nanoviruses, Faba bean necrotic stunt virus (FBNSV) and Pea necrotic yellow dwarf virus (PVYDV) have been reported [25, 26]. The genus Babuvirus included only, Banana bunchy top virus (BBTV). Recently, Abaca bunchy top virus (ABTV) and Cardamom bushy dwarf virus (CBDV) have been reported as new virus species under Babuvirus [60, 84, 87]. There is only one unassigned species, Coconut foliar decay virus (CFDV). At present, a total of nine different viruses are known under the family Nanoviridae (Table 2). The guidelines for demarcation of species within the genus have been prescribed by ICTV. The criteria for defining species are <75% identity in overall nucleotide sequence, differential serological reaction, >15% difference in coat protein sequence and differential natural host.

Table 2.

Taxonomic distribution of members under the family Nanoviridae

| Genus | Species | Acronym |

|---|---|---|

| Babuvirus | Banana bunchy top virus | BBTV |

| Abaca bunchy top virus | ABTV | |

| Cardamom bushy dwarf virus | CBTV | |

| Nanovirus | Subterranean clover stunt virus (type species) | SCSV |

| Faba bean necrotic yellows virus | FBNYV | |

| Faba bean necrotic stunt virus | FBNSV | |

| Pea necrotic yellow dwarf virus | PNYDV | |

| Milk vetch dwarf virus | MDV | |

| Unassigned species | Coconut foliar decay virus | CFDV |

Recognised species is in italic

Geographical Distribution

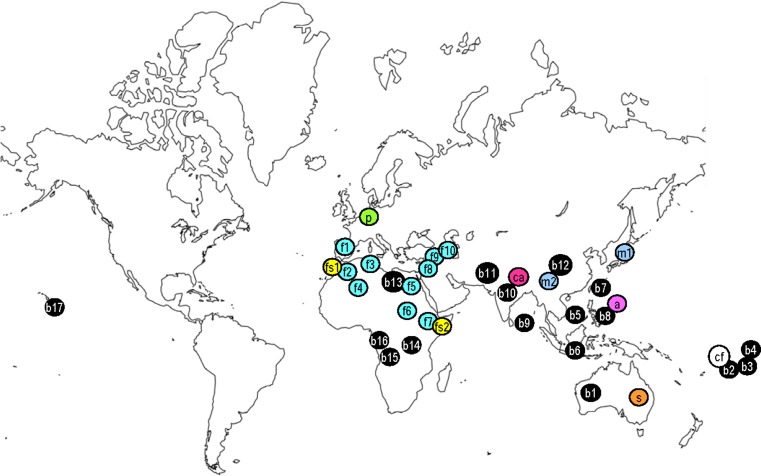

Both nanoviruses and babuviruses are distributed in tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, Australia, Europe and Africa (Fig. 1). BBTV is widely distributed in banana growing countries in the Asia, Pacific region (Australia, China, Guam, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Hawaii, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan, Tonga, Samoa and Vietnam) and in a few countries in Africa (Egypt, Gabon, Angola and Burundi) [2, 16, 50, 89, 99]. There are many other banana growing regions, South and Central America, the Caribbean, Papua New Guinea, Thailand and in many countries in African and Asia, where BBTV has not been confirmed [43, 89]. ABTV is distributed in Abaca growing regions of the Philippines [87]. CBDV affecting large cardamom is distributed in eastern sub-Himalayan mountains of India [60]. SCSV and MDV occur in Australia and Japan, respectively. Recently, MDV has been recorded in China [49]. FBNYV occurs in many Arab countries of West Asia, North and East Africa and Europe (Syria, Jordan, Ethiopia, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Sudan, Azerbaijan, Tunisia and Spain) [20, 21, 44, 48, 54, 56–59, 72]. FBNSV has been recently reported from Ethiopia [25] and Morocco [1], and PNYDV from Germany [26].

Fig. 1.

Global distribution of multicomponent ssDNA plant viruses. b Banana bunchy top virus (BBTV) (b1 Australia, b2 Fiji, b3 Tonga, b4 Samoa, b5 Vietnam, b6 Indonesia, b7 Taiwan, b8 Philippines, b9 Sri Lanka, b10 India, b11 Pakistan, b12 China; b13 Egypt, b14 Burundi, b15 Angola, b16 Gabon, b17 Hawaii); a Abaca bunchy top virus (Philippines), ca Cardamom bushy dwarf virus (India), sSubterranean clover stunt virus (Australia), m Milk vetch dwarf virus (MDV) (m1: Japan; m2: China), fFaba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV) (f1 Spain, f2 Morocco, f3 Tunisia, f4 Egypt, f6 Sudan, f7 Ethiopia, f8 Jordon, f9 Syria, f10 Azerbaijan), cf Coconut foliar decay virus (CFDV) (Vanuatu), p Pea necrotic yellow dwarf virus (Germany), fs Faba bean necrotic stunt virus (fs1 Morocco, fs2 Ethiopia)

Hosts and Vectors

Most of the members under Nanoviridae have limited host range and are aphid-borne except, CFDV, which is transmitted by a plant hopper, Myndus taffini (Table 3). They are transmitted in a circulative, nonpropagative and nontransovarial manners [22, 59]. These viruses generally multiply in phloem tissues and are not transmitted mechanically or through seeds.

Table 3.

Insect vectors of nanoviruses and babuviruses

| Name of the virusa | Insect vector | Mode of transmission | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBTV | Aphid (Pentalonia nigronervosa) | Persistent | [52] |

| ABTV | Aphid (Pentalonia nigronervosa) | Persistent | [70] |

| CBDV | Aphid (Pentalonia nigronervosa) | Persistent | [96] |

| CFDV | Plant hopper (Myndus taffini) | Semi-persistent | [41] |

| FBNYV | Aphid (Aphis craccivora, Acyrthosiphon pisum, Aphis fabae) | Persistent | [21] |

| FBNSV | Aphid (Aphis craccivora, Acyrthosiphon pisum) | – | [25] |

| PNYDV | Aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) | – | [26] |

| MVDV | Aphid (Aphis craccivora, A. gossypii, A. fabae, Acyrthosiphon pisum and Megoura viciae) | Persistent | [38] |

| SCSV | Aphid (Aphis gossypii, Myzus persicae and Macrosiphum euphorbiae) | Persistent | [29] |

aFull name of the virus as is in Table 2

Babuviruses infect limited monocot species under family Musaceae and Zingiberaceae, and are not known to infect any legume hosts. Babuviruses have limited aphid vectors, Pentalonia nigronervosa and Micromyzus kalimpongensis [6, 52, 96]. Nanoviruses naturally infect legumes (dicots), and are vectored by several aphid species. Aphis craccivora appears to be the major natural vector of FBNYV and MDV as it is the most abundant aphid species on legume crops and the most efficient vector under experimental conditions. In addition to A. craccivora, other aphid species such as A. gossypii, A. fabae, Acyrthosiphon pisum, and Megoura viciae are able to transmit MDV at various efficiencies. SCSV has been reported to be vectored by A. gossypii, M. persicae and Macrosiphum euphorbiae [29].

Genome Organisation

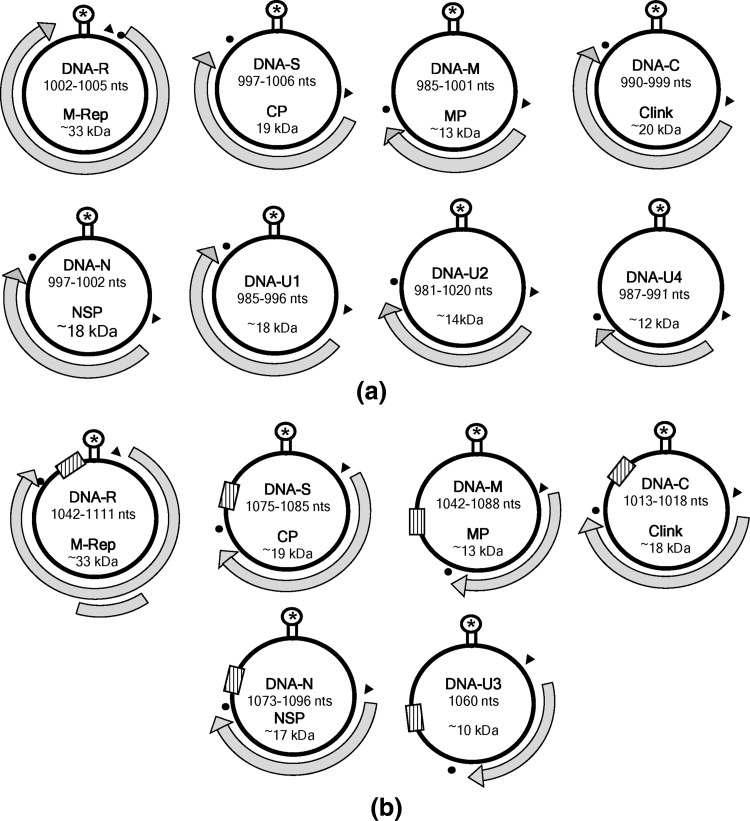

The basic genome structure of the members under Nanoviridae has some similarities to geminivirus. Each circular ssDNA component contains one open reading frame (ORF) in virion sense strand and the noncoding intergenic region with a stem-loop structure (Fig. 2). The loop containing a conserved nona-nucleotide sequence is generally identical among the DNA components of a virus and has minor variation among the members. The stem and loop structure is the origin of replication [93]. The DNA components encoding the major viral proteins are replication associated protein (Rep = DNA-R), coat protein (CP = DNA-S), cell-cycle link protein (Clink = DNA-C), movement protein (MP = DNA-M) and a nuclear shuttle protein (NSP = DNA-N) (Table 4). Each coding region is preceded by a promoter sequence with a TATA box and followed by a poly-A signal. The replication of Babuvirus and Nanovirus is through rolling circle mechanism. In many of the Nanovirus or Babuvirus, several ssDNA components have been shown to encode Rep related proteins, of which only one Rep component that controls replication of other ssDNA components is known as master Rep (M-Rep) [94]. Replication of the DNAs is facilitated and enhanced by the action of 19 kDa Clink, a cell cycle linked protein [4].

Fig. 2.

Genome organization of multicomponent ssDNA plant viruses. M-Rep master Rep, CP coat protein MP movement protein, NSP nuclear shuttle protein, C cell-cycle linking protein, U1–U3 unknown function; * stem and loop structure, solid triangle TATA box, dot poly-A signal. In Babuvirus, hatched box indicate major common region. No ORF was identified in U3 component of Abaca bunchy top virus. a Nanovirus, b Babuvirus

Table 4.

Genome components of the viruses under Nanoviridae

| Designation of DNA component | DNA component numbera | Protein function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBNYV | MDV | SCSV | BBTV | ABTV | ||

| DNA-R | 2 | 11 | 8 | 1 | + | Replication |

| DNA-S | 5 | 9 | 5 | 3 | + | Encapsidation |

| DNA-C | 10 | 4 | 3 | 5 | + | Cell-cycle link protein |

| DNA-M | 4 | 8 | 1 | 4 | + | Movement protein |

| DNA-N | 8 | 6 | 4 | 6 | + | Nuclear shuttle protein |

| DNA-U1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | – | – | Unknown |

| DNA-U2 | 6 | 7 | – | – | – | Unknown |

| DNA-U3 | – | – | – | 2 | + | Unknown |

| DNA-U4 | 12 | – | – | – | – | Unknown |

aThe number indicates the designation of specific DNA components isolated

+Two clones were isolated (one each from two isolates of ABTV) for each of the genome component. Specific number was not used to designate each DNA component

Up to 12 distinct DNA components have been isolated from plants infected by different nano- or babuviruses. Only a single CP has been found to be associated with the viral capsid, which is about 19 kDa [100]. All the Nanovirus DNAs code for only a single protein except, in BBTV, where the M-Rep encoding ORF contains additional 5 kDa protein of unknown function. Being multi-component virus, the number of ssDNA components that are required for inducing disease was not known until 2006, when Timchenko et al. [95] demonstrated infectivity of the cloned DNAs of FBNYV through agroinoculation. Only five DNA components DNA-R, DNA-S, DNA-M, DNA-U1 and DNA-U2 were enough to produce disease, however, the progeny viruses could not be transmitted through aphid vectors. The first comprehensive demonstration of infectivity of the cloned DNAs was shown for FBNSV. A group of eight cloned DNA components produced typical disease symptoms as well as biologically active progeny virus that was successfully transmitted through aphid vector [25].

Disease and Virus Description

Bunchy Top of Banana

Bunchy top of banana is the one of the earliest known and significant plant viral diseases. Banana being vegetatively propagated, the disease spreads widely through planting material. The banana bunchy top disease was first observed of in Fiji in 1889. It emerged as a serious threat to banana cultivation in many countries, including Fiji in 1927, Egypt and India in 1953, the Philippines and Taiwan in 1961, Tonga and Samoa in 1967, China in 1979, Pakistan and Hawaii in 1989 [2, 16]. In Australia, the banana industry in south-east Queensland and northern New Wales was virtually destroyed by the bunchy top disease in 1920 [16]. In India, the disease was introduced from Sri Lanka during 1940 through southern India and now it has spread all over the banana growing region. Of all the known banana viruses, BBTV is the most serious viral pathogen of banana.

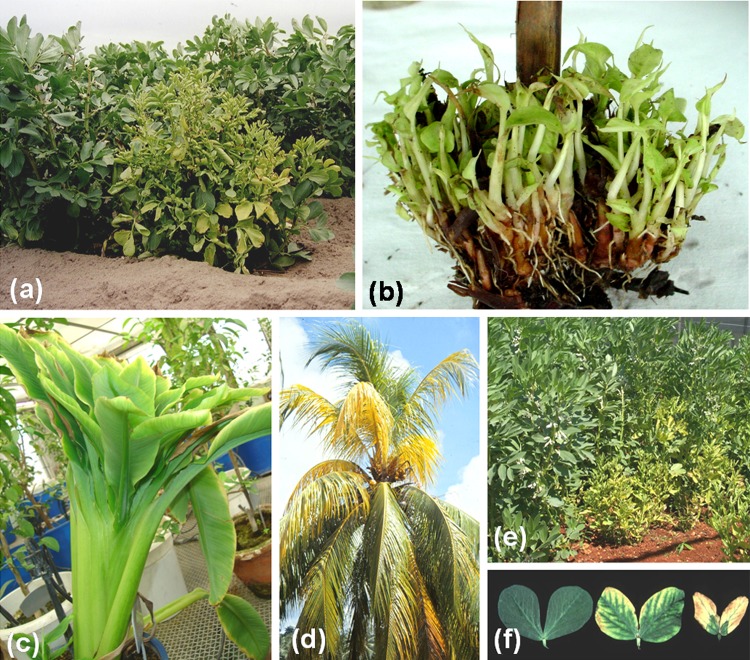

Initial disease symptoms are not very conspicuous. The characteristic symptoms are produced at the advanced stage of infection. Initially, dark green streaks appear on petiole, midrib and veins of the leaves. Finally, the affected plants become stunted containing a bunch of short, narrow, erect and chlorotic leaves, which gives bunchy appearance on the crown of the plant (Fig. 3c). The severely affected plant does not produce fruits and dies eventually resulting in a total loss. The virus is naturally transmitted by aphid, Pentalonia nigronervosa in a persistent manner and through vegetative propagation of sucker from infected plants [51, 52]. Vector transmission rate is directly proportional to the number of viruliferous aphids and inversely proportional to the age of plant [102]. Transmission of BBTV by P. nigronervosa is influenced by temperature, vector life stage and plant access period [3].

Fig. 3.

Disease symptoms of multicomponent ssDNA plant viruses. aMilk vetch dwarf virus (MDV) in faba bean showing yellowing; b Cardamom bushy dwarf virus in large cardamom showing excessive stunting and proliferation of lateral shoots; cBanana bunchy top virus (BBTV) in banana showing bunchy crown; d Coconut foliar decay virus (CFDV) in coconut (Malayan Red Dwarf) showing yellowing of fronds; eFaba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV) in faba bean showing yellowing and stunting; f FBNYV in faba bean leaves showing marginal chlorosis and necrosis. (Source of figures: BBTV on banana was contributed by Dr. VK Baranwal, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, India; MDV on faba bean by Dr. Y Sano, Niigata University, Japan; FBNYV on faba bean by Dr. SG Kumari, ICARDA, Syria; CFDV on coconut by Dr. JW Randles, University of Adelaide, Australia)

BBTV

Determination of the causal virus of banana bunchy top ran in to confusion for a while. Research progress on BBTV was slow compared to the other important plant viruses. Purification of the virus from infected banana plants is difficult due to low concentration of virus and difficult tissue type. Initially, BBTV was considered as a possible member of the luteovirus on the basis of yellowing symptoms, cytopathological effect on phloem and aphid transmission [17, 63]. During 1989–1990, the reports of virus purification from bunchy top affected banana were published by two independent groups of worker from Gabon (Africa) and Taiwan [39, 91]. The African group reported presence of isometric virus of 28 nm and the Taiwan group reported 20–22 nm isometric virus. Further, observation of dsRNA was observed with the diseased plant [17] and ssRNA with the purified preparation [103] supported the idea of luteovirus association.

The first successful demonstration of association of ssDNA virus with the disease was from two laboratories in Australia in 1991 [31, 92]. They concluded that the BBTV virions were isometric with a diameter of 18–20 nm with buoyant density of 1.28–1.30 g/ml in caesium sulphate and sedimentation coefficient of 46S in isokinetic sucrose density gradients. The A260/A280 of purified preparations was about 1.33. The purified virus preparation contained ssDNA of about 1 kb and a single coat protein Mr 20500–20100. Both the polyclonal antibodies and DNA probe prepared from the purified virus detected BBTV by ELISA in field-infected banana plants and in aphid [31, 92].

The first genome sequence information was generated in 1993 on component-1 DNA of BBTV genome, which was circular ssDNA consisting of 1111 nucleotides encoding one large ORF of 858 nucleotides in virus strand encoding a protein of 286 amino acids with a Mr of 33.6K. The protein was identified as a replicase based on the presence of a dNTP binding motif (GGEGKT) [32]. The noncoding region contains a stem and loop structure. The loop contains nonanucleotide sequence (TATTATTAC), which was nearly identical to that of geminivirus (TAATATTAC) and CFDV (TAGTATTAC). The sequence of BBTV component-1 was not significantly similar to any plant DNA viruses except CFDV [82] and SCSV [14]. The component-1 DNA was detected in all bunchy top affected plant samples from 10 different countries indicating an integral part of BBTV genome. Based on component-1 sequence, existence of two groups of BBTV isolates were evident: the South Pacific group containing isolates from Australia, Burundi, Egypt, Fiji, India, Tonga and Western Samoa; and the Asian group containing isolates from the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam [43]. The mean sequence difference within each group was 1.9–3.0% and between the isolates from the two groups was about 10%. BBTV occurring in Indian [99] and Pakistan [2] has been characterized based on sequence of 5–6 components of DNA and both the isolates belonged to the South Pacific group. Phylogenetic analysis of major common region of all the six DNA components of BBTV showed a possible concerted evolution within the Pacific group due to recombination in this region [37].

During 1994–1995, additional DNA components were cloned and sequenced, which provided the evidence that BBTV was a multi-genomic virus containing at least seven ssDNA components [9, 10, 105, 106]. The DNA components of BBTV have potential source of promoters. Assessment of DNA components 1-6 showed that the promoters are functional in both monocot and dicot plants [19]. Promoter from DNA component-2 showed greater efficacy compared to 35S promoter from Cauliflower mosaic virus.

The functions of various DNA components of BBTV have been addressed. DNA component-1 encoded a Rep protein [10, 32, 37]. Two mRNA transcripts were identified from component-1 of BBTV; larger one transcribed from Rep ORF and the shorter transcript mapped completely internal to Rep ORF [7]. The smaller transcript encoding 5 kDa protein of unknown function is unique and not known in the corresponding DNA component of nanoviruses. The DNA component-3 was shown to encode the CP [100]. The protein encoded by component-4 was found to localised in cell periphery, whereas, the protein encoded by component-3 and -6 were in both nucleus and cytoplasm. The component-6 was identified to encode a NSP, while the component-4 to encode a movement protein [101]. The characteristics of the proteins encoded by BBTV DNA-4 and DNA-6 are very similar to those of the BC1 (movement) and BV1 (nuclear shuttle) proteins, respectively of Squash leaf curl virus and other begomoviruses [67, 85]. Based on yeast two-hybrid analysis and occurrence of LXCXE motif, component-5 was identified to encode the clink, a retinoblastoma-binding like protein [101].

Three possible satellite DNAs have been isolated from BBTV infected banana; BBTV S1 [35], BBTV Y/X [104, 106] and BBTV S2/W2 [35, 104]. Unlike, BBTV DNA component-1 to -6, S1 and S2 appear to be prevalent in Asian group of isolates rather than in South Pacific isolates [35]. Unlike component-1, these satellite DNA components are not mandatory for the replication of the BBTV. The DNA component-1 is the minimal replicative unit of BBTV and is required for replication of other components and therefore, it was identified as the M-Rep [36]. Three iteron with sequence GGGAC (F1, F2 and R) have been identified in the intergenic region of DNA components of BBTV. Interaction of Rep with the iteron is essential for efficient DNA replication [34].

Bunchy Top of Abaca

Abaca or Manila hemp (Musa textilis) is a fiber crop mainly grown in Philippines. The fiber is mainly used in fabrics, bank notes, lens-cleaning tissue, tea bags and capacitor papers [80]. About 75% of the total abaca fiber is produced in the Philippines. In the Philippines, abaca bunchy top disease was first broke out in 1915 in Cavite and Silang provinces and by 1980, the disease spread in Bicol, a major abaca region [68, 69]. The disease occurs in all major production areas and is a major factor in the decline of abaca export from the Philippines [79, 80]. The quantitative estimate of losses due to bunchy top is not available; however, the disease is very destructive. In Cavite province, about 12000 ha of abaca was wiped out in 1928 [11].

The symptoms of the abaca bunchy top disease include presence of chlorotic areas on the youngest furled leaf, progressive narrowing and shortening of the new leaves, dark green flecks or vein clearing of the minor leaf veins and chlorosis of leaf margins. The false stem becomes stunted but the girth of the upper end may be same or greater than the lower end. The infected abaca plants survive for about two years, gradually become smaller and finally all of the leaves and leaf sheaths turn brown and die. The disease is naturally transmitted by the banana aphid, Pentalonia nigronervosa [68].

ABTV

Bunchy top disease of banana and abaca were considered to be caused by a same virus due to similar symptoms and transmission [53, 70]. The disease in abaca could be induced by BBTV isolated from banana (Magee, 1927). But Sharman et al. [87] reported that the virus causing abaca bunchy top disease is distinct from BBTV. The viruses were serologically distinct and shared only 79–81% amino acid sequence identity of the putative coat protein. Overall nucleotide sequence identity with BBTV across all components ranges between 54–76%. In the phylogenetic analyses, ABTV and BBTV each located together but on separate branches separating from nanoviruses. The genome of ABTV consisted of at least six circular ssDNA of about 1.0–1.1 kb each. However, unlike BBTV, ABTV isolate lack an internal ORF in the DNA-R component.

Foorkey of Large Cardamom

Foorkey disease of large cardamom (Ammomum subulatum) is known since 1936 in Darjeeling hills, India [66]. The affected plants result into profuse vegetative growth of excessively stunted tillers from the rhizome (Fig. 3b). The stalks are greatly reduced and the leaves become pale green and slightly curled. The diseased plants survive for few years and remain unproductive. The foorkey disease was considered to be caused by a virus different from those causing bunchy top of banana and katte disease of small cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) [96]. The foorkey is not sap or seed transmissible, however it is transmitted by the banana aphid, P. nigronervosa in a persistent manner [96]. Basu and Ganguly [6] reported that at Kalimpong, the foorkey was transmitted by another aphid, Mycromyzus kalimpongensis, but not by the banana aphid. The virus could be transmitted to both large and small cardamom, but not to Musa sapientum, Gladiolus sp, Canna indica, Zingiberofficinale, Triticum aestivum, Sorghum vulgare and Zea mays [96].

CBDV

In leaf-dip electron microscopy, hardly any virus like structure is visible in the foorkey affected large cardamom samples. Partially purified preparation contained a few isometric particles of 17–20 nm. ELISA with polyclonal antisera to BBTV showed weak serological reaction. Nucleotide sequence of Rep gene showed 80–82% identity with that of BBTV and 47.6–48.5% identity with the nanoviruses. Based on this information along with the available biological properties, association of a new Nanovirus, Cardamom bushy dwarf virus (CBDV) was identified with the foorkey disease of large cardamom [60]. Six distinct full-length DNA components encoding putative master-Rep (M-Rep), non-master-Rep, coat protein and three DNA components of unknown function (FrU1, FrU2 and FrU3) were cloned and sequenced, which showed phylogenetic affinity with babuviruses [61, 84].

Stunt of Subterranean Clover

Subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum) and several other pasture and grain legumes (pea, French bean and broad bean) in Australia are affected by a stunt disease [28, 29, 90]. The disease was initially observed in New South Wales, Tasmania, Victoria and Queensland. The disease caused yield losses of up to 65% [28]. The characteristic symptoms of the disease are severe stunting with marginal yellowing and cupping of young leaves and reddening of older leaves.

SCSV

Initially, the disease was thought to be caused by mineral deficiency [65]. Subsequently, it was shown to be an aphid transmitted virus [28, 29]. SCSV was persistently transmitted by Aphis craccivora and Myzus persicae. However, it was not sap or seed transmissible. Novel virus-like isometric particles of 17–19 nm were purified from subterranean clover and pea plant affected with the stunt disease [13]. Purified SCSV particles did not induce disease on subterranean clover inoculated with aphid (Aphis craccivora) fed on the purified preparation [14]. The virus particles had a T = 1 capsid structure containing 60 polypeptide subunits each with Mr of 19,000. SCSV has a functionally divided genome composed of multiple circular, ssDNA molecules of about 1 kb, each of which are encapsidated in a separate particle with a short complementary primer sequence [13, 14]. The sequence of eight circular, ssDNA components of SCSV has been determined so far [8, 94]. All components contain a single ORF in sense direction and a stable stem-loop structure in the noncoding region. The loop contains a conserved nonanucleotide sequence (TAGTATTAC).

Necrotic Yellows of Faba Bean and Other Legumes

Necrotic yellows are important viral diseases of several important food and fodder legumes in Western Asia and North Africa [55]. Faba bean (Vicia faba) is an important crop affected by the disease. In addition, several cool season (Lens culinaris, Cicer arietinum and Pisum sativum) and summer season legumes (Phaseolus vulgaris and Vigna unguiculata) are also affected by the disease [20, 44, 54, 58]. The disease (Fig. 3e, f) causes yellowing, rolling and necrosis of leaves and stunting and death of plants. The disease was first observed in Syria in 1988. During 1991–1992 and in 1998, the disease caused complete crop failure in faba bean in Egypt [55, 58]. The disease was persistently transmitted by various aphid species, of which Aphis craccivora was the most significant natural vector [22]. The disease could be transmitted through A. craccivora to a new host, Arabidopsis thaliana [97].

FBNYV

Isometric virus of 18 nm containing circular ssDNA as genome of 1.0 kb was observed in faba bean affected with necrotic yellows and the virus was named as FBNYV [44]. By host range, transmission and serology, the virus was similar to SCSV and MDV. In 1995, the first sequence information was obtained for the component-1, which contained 1002 nucleotides encoding 32.3 kDa Rep protein [45]. The sequence information showed that the FBNYV is a distinct virus with similarities to other nanoviruses. Five more components (C2–C6) of FBNYV were determined; C2 encoded an additional Rep of 33.1 kDa, C4 encoded MP, C4 and C5 encoded 19 kDa CP and C3 and C6 encoded proteins of unknown function [46]. Further, additional four components (C7–C10) of ssDNA were isolated and characterized [47]. The C7 and C9 encoding Reps were similar to C1 and C2. C8 encoded 17.4 kDa protein of unknown function and C10 encoded clink protein. A total of 12 components were characterised for FBNYV and this provided evidence that FBNYV was a multicomponent ssDNA virus and a distinct species under the genus Nanovirus. Five different DNA components (C1, C2, C7, C9 and C11) are known to encode different but closely related Rep in FBNYV. Only, C2 was shown to support replication of all the six other genome components. Further, only the C2 DNA was always detected in 55 samples of FBNYV from eight countries. These provided evidence of existence of a master replication protein (M-Rep) encoded by FBNYV [93].

In 2000, Aronson et al. identified the function of C10 component, which encoded a 20 kDa protein that interacted with cell-cycle regulators retinoblastoma-like proteins (pRB). The FBNYV-C10 encoding protein has been named as Clink protein due to its potential to link viral DNA replication with key regulatory pathways of the cell-cycle. Clink significantly increases replication of FBNYV DNA. The interaction of Clink with pRB and SKP1 has been demonstrated in yeast two-hybrid system and in vitro by pull-down assays with the proteins expressed in E. coli [4]. Similar interaction occurring in plant was demonstrated by FBNYV-based expression vector system [5].

FBNYV or any other nanoviruses contains multicomponents of ssDNA. It was not known that how many components were necessary for causing disease. Timchenko et al. [95] for the first time demonstrated infectivity of the FBNYV cloned DNAs. Ony five DNAs, DNA-R, DNA-S, DNA-M, DNA-U1 and DNA-U2 were sufficient to induce disease symptoms in Vicia faba following agroinoculation. The inoculated plants with FBNYV DNAs produced virions but they were not transmitted by Aphis craccivora or Acyrthosiphon pisum-the two efficient aphid vector of FBNYV.

Necrotic Stunt/Dwarf of Faba Bean and Pea

Faba bean necrotic stunt was first observed in Ethiopia [23] and subsequently recorded in Morocco [1]. The virus causing the necrotic stunt in faba bean has been identified as a new Nanovirus species, FBNYV. Eight distinct DNA components were characterised and inoculation with these cloned DNAs produced typical disease in faba bean. The progeny virus of the cloned DNAs was transmissible by its vector, Aphis craccivora and Acyrthosiphon pisium [25]. This is the first conclusive demonstration about the infective unit of Nanovirus genome.

Pea necrotic yellow dwarf was first observed in 2009 in Germany [26]. The disease is characterized by severe yellowing, necrosis and stunting of plant and is transmitted by pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisium but not by sap. A new Nanovirus species, PNYDV was identified to be associated with the disease. PNYDV is serologically different from other nanoviruses. Only Rep encoding DNA component has been sequenced, which shared 73–79% sequence identity with that of FBNYV, FBNSV, MDV and SCSV [26].

Dwarf of Milk Vetch and Other Legumes

Yellowing and dwarfing of Chinese milk vetch (Astragalus sinicus), a common green manure crop was first reported in Japan [38, 62]. The disease is transmitted by Aphis craccivora and known to affect other legumes, faba bean (Fig. 3a), broad bean, pea and soybean. Now, MDV is known to occur in China [49].

MDV

Initially, MDV was thought to be a luteovirus based on symptoms, vector and presence of 25 nm virus particles [71]. The correct identity as a Nanovirus was evident in 1998, when the genome sequence information was obtained [86]. Prior to this, Nanovirus like virus particles of 18 nm containing circular ssDNA of 1 kb were obtained in pea leaves [40]. Ten ssDNA components of MDV have been cloned and sequenced; these are designated as C1–C10 [86]. The DNA components of MDV were similar to SCSV and FBNYV.

Analysis of the predicted amino acid sequences revealed that C1, C2, C3 and C10 all encoded distinct Rep proteins of 33 kDa, which show only 42–57% amino acid identity. MDV-C7 and FBNYV-C6 each encode a 15 kDa protein, which was not present in SCSV and BBTV. C11 (DNA-R) encoded the M-Rep, required for replication of all the other genomic DNAs [94]. Based on the sequence similarity between proteins of different nanoviruses, C4, C6, C8 and C9 were identified to encode Clink, NSP, MP and CP, respectively [98]. The function of the proteins encoded by C5 (DNA-U1) and C7 (DNA-U2) is unknown. The promoter activity of the MDV DNA components (C1–C11) has been characterized [88]. The components, C4–C8 showed stronger GUS activity compared to 35S promoter. The M-Rep and other Rep encoding components (C1, C2, C3, C10 and C11) showed low level of promoter activity.

Foliar Decay of Coconut

The foliar decay, a lethal disease was first observed in introduced varieties of coconut (Cocos nucifera) palms in Vanuatu, formerly New Hebrides during 1979–1980 [12, 18, 41]. Symptoms (Fig. 3d) are characterized by appearance of yellowing in several leaflets of the fronds between 7 and 11 positions down the crown from the unopened spear leaf. This is followed by yellowing, necrosis and death of fronds and crown. The dead fronds hang downward from the petiole and other fronds become yellow and plants die eventually.

The affected plant produces inflorescence that develops normal but a fewer nuts. Susceptible trees usually die within 1–2 years of the appearance of symptoms. The local variety, ‘Vanuatu Tall’ is symptomless and the hybrids developed from this variety exhibit mild symptoms [12, 42]. The cultivar, Malayan Red Dwarf is highly susceptible and is used as an indicator plant for epidemiological and insect transmission studies. The virus was not transmitted by seeds or pollen, but by the plant hopper, Myndus taffini. The plants inoculated through vector, M. taffini produce symptoms at 6–11 months post inoculation [41, 42].

CFDV

The etiology of coconut foliar decay disease was a puzzle for a long time. No fungi, bacteria and nematode were associated with the disease [42]. No virus or microorganism was detected by electron microscopy and detection of coconut cadang cadang viroid was also negative [74]. Association of a single-stranded DNA with sedimentation coefficient <75S and buoyant density of about 1.36 g/ml in Cs2SO4 was reported with the coconut plant showing foliar decay disease induced by feeding of M. taffini [75, 76]. Association of isometric virus particles of 20 nm with the foliar decay disease was first observed by Randles and Hanold [73]. Later on, Rohde et al. [82] have characterized a ssDNA component associated with the CFDV by cloning and sequencing. The ssDNA molecule contained 1291 nucleotides with the potential of at least six ORFs, one of which (ORF1) coded for a leucine-rich protein (33.4 kDa) with the nucleoside triphosphate-binding motif GXGKS indicating a Rep protein. The DNA sequence contained a stable stem and loop structure, which resembles to that of geminiviruses. The DNA sequence data, however, did not resemble any known taxonomic group of plant viruses. CFDV is localized within the phloem of coconut palms. Multiple sampling is needed for reliable diagnosis as CFDV as it is distributed unevenly in whole plants in a non-symptomatic manner, and a minimum sampling should include tissue from fronds 1, 3 and 5, and secondary roots [77].

To determine the promoter activity of CFDV DNA in plant, reporter gene was fused to the CFDV DNA and tobacco plants were transformed. The expression of the reporter gene was obtained in the phloem tissue of the vascular system in stem, leaves and flower demonstrating the association of CFDV DNA with the phloem [83]. The cis-signals involved in CFDV promoter strength and tissue specificity were identified and it was shown that, CFDV stem-loop structure dramatically influences transcriptional efficiency [33]. The Rep protein of CFDV was expressed as a 6× His recombinant protein and it was demonstrated that the protein possessed sequence non-specific RNA- and ssDNA-binding activities as well as magnesium-dependent ATPase/GTPase activity [64]. The Rep protein was also able to interact with itself and associated predominantly with nuclei and membranes of infected/transfected cells [64]. The Rep activity of CFDV was very similar to those reported for Reps of geminiviruses.

Concluding Remarks

The family Nanoviridae containing multigenomic small isometric plant viruses is relatively young and is expanding. The family includes two distinct groups of members that are divided into two genera, Nanovirus and Babuvirus [98]. The name Nanovirus was originally coined to represent small isometric multigenomic plant viruses. Now, Nanovirus refers to only one of the genera and therefore no more represents as a common name for the members under the family. As the members under the present genus, Nanovirus have a common character of infecting legumes, a new name of this genus, ‘Lenovirus’ derived from legume Nanovirus may be more meaningful instead of Nanovirus.

Multicomponent ssDNA plant viruses although were identified in 1990s, many of them are known to exist for a long time as they are associated with historic plant diseases and some of them have recently emerged [25, 26]. Genomics of these viruses opened up new area of studies that they are the source of promoters [19, 83, 88] for gene expression in plant and vectors that provide efficient expression system for studying in planta protein-protein interactions [5].

Acknowledgements

Author is thankful to Dr. J. W. Randles, Dr. Y. Sano, Dr. V. K. Baranwal and Dr. S.G. Kumari for providing the pictures of CFDV, MDV, BBTV and FBNYV affected plants, respectively.

References

- 1.Abraham AD, Bencharki B, Torok V, Katul L, Varrelmann M, Vetten HJ. Two distinct nanovirus species infecting faba bean in Morocco. Arch Virol. 2010;155:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0548-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin I, Qazi J, Mansoor S, Ilyas M, Briddon RW. Molecular characterisation of banana bunchy top virus (BBTV) from Pakistan. Virus Genes. 2008;36:191–198. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0168-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anhalt MD, Almeida RPP. Effect of temperature, vector life stage, and plant access period on transmission of Banana bunchy top virus to banana. Phytopathology. 2008;98:743–748. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-98-6-0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson MN, Meyer AD, Gyorgyey J, Katul L, Vetten HJ, Gronenborn B, Timchenko T. Clink, a nanovirus-encoded protein, binds both pRB and SKP1. J Virol. 2000;74:2967–2972. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.7.2967-2972.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson MN, Complainville A, Clerot D, Alcalde H, Katul L, Vetten HJ, Gronenborn B, Timchenko T. In planta protein-protein interactions assessed using a nanovirus-based replication and expression system. Plant J. 2002;31:767–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basu AN, Ganguly B. A note on the transmission of foorkey disease of large cardamom by the aphid, Micromyzus kalimpongensis Basu. Indian Phytopathol. 1968;21:127. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beetham PR, Hafner GJ, Harding RM, Dale JL. Two mRNAs are transcribed from banana bunchy top virus DNA-1. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:229–236. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boevink P, Chu PWG, Keese P. Sequence of subterranean clover stunt virus DNA: affinities with the geminiviruses. Virology. 1995;207:354–361. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns TM, Harding RM, Dale JL. Evidence that banana bunchy top virus has a multiple component genome. Arch Virol. 1994;137:371–380. doi: 10.1007/BF01309482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns TM, Harding RM, Dale JM. The genome organization of banana bunchy top virus: analysis of six ssDNA components. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:1471–1482. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-6-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calinisan MR, Hernandez CC. Studies on the control of abaca bunchy top with reference to varietal resistance. Philipp J Agric. 1939;7:393–408. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvez C, Renard JL, Marty G. Tolerance of the hybrid coconut Local × Rennell to New Hebrides disease. Oleagineux. 1980;35:443–451. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu PWG, Helms K. Novel virus-like particles containing circular single-stranded DNAs associated with subterranean clover stunt disease. Virology. 1988;167:38–49. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu PWG, Paula K, Bing-shengb Q, Waterhouse PM, Gerlach WL. Putative full-length clones of the genomic DNA segments of subterranean clover stunt virus and identification of the segment coding for the viral coat protein. Virus Res. 1993;27:161–171. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(93)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu PWG, Boevink P, Surin B, Larkin P, Keese P, Waterhouse P. Non-geminated single-stranded DNA plant viruses. In: Singh RP, Singh US, Kohmoto K, editors. Pathogenesis and host specificity in plant diseases, viruses and viroids. Tarrytown: Pergamon Press; 1995. pp. 311–341. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dale JL. Banana bunchy top, an economically important tropical plant virus. Adv Virus Res. 1987;33:301–325. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dale JL, Phillops DA, Parry JN. Double-stranded RNA in banana plants with bunchy top disease. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:371–375. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-2-371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dollet M, Taffin G. Progress report on the virological study of the New Hebrides coconut disease. Document 1437, IRHO, Paris; 1979.

- 19.Dugdale B, Beetham PR, Becker DK, Harding RM, Dale JL. Promoter activity associated with the intergenic regions of banana bunchy top virus DNA-1 to -6 in transgenic tobacco and banana cells. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2301–2311. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-10-2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franz A, Makkouk KM, Vetten HJ. Faba bean necrotic yellows virus naturally infects Phaseolus bean and cowpea in the coastal area of Syria. J Phytopathol. 1995;143:319–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1995.tb00267.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franz A, Makkouk KM, Vetten HJ. Host range of faba bean necrotic yellows virus and potential yield loss in infected faba bean. Phytopathol Mediterr. 1997;36:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franz A, Makkouk KM, Vetten HJ. Acquisition, retention and transmission of faba bean necrotic yellows virus by two of its aphid vectors, Aphis craccivora (Koch) and Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris) J Phytopathol. 1998;146:347–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1998.tb04703.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franz A, van der Wilk F, Verbeek M, Dullemans AM, van den Heuvel JF. Faba bean necrotic yellows virus (genus Nanovirus) requires a helper factor for its aphid transmission. Virology. 1999;262:210–219. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbs MJ, Weiller GF. Evidence that a plant virus switched hosts to infect a vertebrate and then recombined with a vertebrate-infecting virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8022–8027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grigoras I, Timchenko T, Katul L, Grande-Pérez A, Vetten HJ, Gronenborn B. Reconstitution of authentic nanovirus from multiple cloned DNAs. J Virol. 2009;83:10778–10787. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01212-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigoras I, Gronenborn B, Vetten HJ. First report of a nanovirus disease of pea in Germany. Plan Dis. 2010;94:642. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-94-5-0642C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gronenborn B. Nanoviruses: genome organization and protein function. Vet Microbiol. 2004;98:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grylls NE, Butler FC. An aphid transmitted virus affecting subterranean clover. J Aust Inst Agric Sci. 1956;22:73–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grylls NE, Butler FC. Subterranean clover stunt, a virus disease of pasture legumes. Aust J Agric Res. 1959;10:145–159. doi: 10.1071/AR9590145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hafner GJ, Stafford MR, Wolter LC, Harding RM, Dale JL. Nicking and joining activity of banana bunchy top virus replication protein in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1795–1799. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding RM, Burns TM, Dale JL. Virus-like particles associated with banana bunchy top disease contain small single-stranded DNA. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:225–230. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-2-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harding RM, Burns TM, Hafner G, Dietzgen RG. Nucleotide sequence of one component of the banana bunchy top virus genome contains a putative replicase gene. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:323–328. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-3-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hehn A, Rohde W. Characterization of cis-acting elements affecting strength and phloem specificity of the coconut foliar decay virus promoter. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:1495–1499. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-6-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrera-Valencia VA, Dugdale B, Harding RM, Dale JL. An iterated sequence in the genome of Banana bunchy top virus is essential for efficient replication. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3409–3412. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horser CL, Karan M, Harding RM, Dale JL. Additional Rep-encoding DNAs associated with banana bunchy top virus. Arch Virol. 2000;145:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s007050050001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horser CL, Harding R, Dale J. Banana bunchy top nanovirus DNA-1 encodes the ‘master’ replication initiation protein. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:459–464. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-2-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu JM, Fu HC, Lin CH, Su HJ, Yeh HH. Reassortment and concerted evolution in Banana bunchy top virus genomes. J Virol. 2007;81:1746–1761. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01390-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inouye T, Inouye N, Mitsuhata K. Yellow dwarf of pea and broad bean caused by milk-vetch dwarf virus. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1968;34:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iskra ML, Garnier M, Bove JM. Purification of banana bunchy top virus. Fruits. 1989;44:63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isogai M, Sano Y, Kojima M. Identification of the unique DNA species in the milk-vetch dwarf virus-infected leaves. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1992;58:631–632. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Julia JF. Myndus taffini (Homoptera Cixiidae), vector of foliar decay of coconuts in Vanuatu. Oleagineux. 1982;37:409–414. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Julia JF, Dollet M, Randles J, Calvez C. Foliar decay of coconut by Myndus taffini (FDMT): new results. Oleagineux. 1985;40:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karan M, Harding RM, Dale JL. Evidence for two groups of banana bunchy top virus isolates. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:3541–3546. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-12-3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katul L, Vetten HJ, Maiss E, Makkouk KM, Lesemann DE, Casper R. Characterisation and serology of virus-like particles associated with faba bean necrotic yellows. Ann Appl Biol. 1993;123:629–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1993.tb04933.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katul L, Maiss E, Vetten HJ. Sequence analysis of a faba bean necrotic yellows virus DNA component containing a putative replicase gene. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:475–479. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-2-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katul L, Maiss E, Morozov SY, Vetten HJ. Analysis of six DNA components of the faba bean necrotic yellows virus genome and their structural affinity to related plant virus genomes. Virology. 1997;233:247–259. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katul L, Timchenko T, Gronenborn B, Vetten HJ. Ten distinct circular ssDNA components, four of which encode putative replication-associated proteins, are associated with the faba bean necrotic yellows virus genome. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:3101–3109. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-12-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumari SG, Attar N, Mustafayev E, Akparov Z. First report of Faba bean necrotic yellows virus affecting legume crops in Azerbaijan. Plant Dis. 2009;93:1220. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-93-11-1220C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumari SG, Rodoni B, Vetten HJ, Loh MH, Freeman A, Leur JV, Shiying Bao S, Wang X. Detection and partial characterization of Milk vetch dwarf virus Isolates from faba bean (Vicia faba L.) in Yunnan Province, China. J Phytopathol. 2010;158:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2009.01572.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lava-Kumar P, Ayodele M, Oben TT, Mahungu NM, Beed F, Coyne D, Londa L, Mutunda MP, Kiala D, Maruthi MN. First report of Banana bunchy top virus in banana and plantain (Musa spp.) in Angola. New Dis Rep. 2008;18:5. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magee CJP. Investigation on the bunchy top disease of the banana. Melbourne: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research; 1927. p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magee CJP. Transmission studies on the banana bunchy top virus. J Inst Agric Sci. 1940;6:109–110. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Magee CJP. Some aspects of the bunchy top disease of banana and other Musa spp. J Proc Roy Soc N S W. 1953;87:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Makkouk KM, Kumari SG. First report of Faba bean necrotic yellows virus and Beet western yellows virus infecting faba bean in Tunisia. Plant Dis. 2000;84:1046. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.9.1046A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Makkouk KM, Kumari HG. Epidemiology and integrated management of persistently transmitted aphid-borne viruses of legume and cereal crops in West Asia and North Africa. Virus Res. 2009;141:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makkouk KM, Bos L, Azzam OI, Kumari SG, Rizkallah A. Survey of viruses affecting faba bean in six Arab countries. Arab J Plant Prot. 1988;6:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Makkouk KM, Kumari SG, Al-Daoud R. Survey of viruses affecting lentil (Lens culinaris Med) in Syria. Phytopathol Mediterr. 1992;31:188–190. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makkouk KM, Rizkallah L, Madkour M, El-Sherbeeny M, Kumari SG, Amriti AW, Solh MB. Survey of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) for viruses in Egypt. Phytopathol Mediterr. 1994;33:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Makkouk KM, Hamed AA, Hussein M, Kumari SG. First report of Faba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV) infecting chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) and faba bean (Vicia faba L.) crops in Sudan. New Dis Rep. 2002;6:11. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mandal B, Mandal S, Pun KB, Varma A. First report of the association of a Nanovirus with ‘Foorkey’ disease of large cardamom in India. Plant Dis. 2004;88:428. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.4.428A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mandal B, Mandal S, Tripathi NK, Barman AR, Pun KB, Varma A. Sequence analysis of DNAs encoding putative replicase gene of nanovirus from large cardamom affected by foorkey disease. Indian J Virol. 2008;19:62. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsuura Y. Studies on the dwarf disease of milk vetch (Astragalus sinicus) Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1953;17:65–68. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Matthews REF. Classification and nomenclature of viruses. Intervirology. 1982;17:1–199. doi: 10.1159/000149278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merits A, Fedorkin ON, Guo D, Kalinina NO, Morozov SY. Activities associated with the putative replication initiation protein of Coconut foliar decay virus, a tentative member of the genus Nanovirus. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:3099–3106. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-12-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Millikan CR. Subterranean clover—symptoms of mineral disorders. J Dept Agric Vic. 1953;51:215–225. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitra M. Report of the imperial mycologist. Pusa: Scientific Report of Agricultural Research Institute; 1936. pp. 1933–1934. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noueiry AO, Lucas WJ, Gilbertson RL. Two proteins of a plant DNA virus coordinate nuclear and plasmodesmal transport. Cell. 1994;76:925–932. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ocfemia GO. Progress report on bunchy-top of abaca or Manila hemp. Phytopathology. 1926;16:894. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ocfemia GO. Second progress report on bunchy top of abaca, or Manila hemp. Phytopathology. 1927;17:255–257. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ocfemia GO. The bunchy-top of abaca and its control. Philipp Agric. 1931;20:328–340. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ohki ST, Doi Y, Yora K. Small spherical virus particles found in broad bean plants infected with milk-vetch dwarf virus. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1975;41:508–510. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ortiz V, Navarro E, Castro S, Carazo G, Romero J. Incidence and transmission of Faba bean necrotic yellows virus (FBNYV) in Spain. Span J Agric Res. 2006;4:255–260. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Randles JW, Hanold D. Coconut foliar decay virus particles are 20-nm icosahedra. Intervirology. 1989;30:177–180. doi: 10.1159/000150090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Randles JW, Palukaitis P. In vitro synthesis and characterization of DNA complementary to cadang-cadang associated RNA. J Virol. 1979;43:649–662. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-43-3-649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Randles JW, Julia JF, Calvez C, Dollet M. Association of single-stranded DNA with the foliar decay disease of coconut palm in Vanuatu. Phytopathology. 1986;76:889–894. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-76-889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Randles JW, Hanold D, Julia JF. Small circular single-stranded DNA associated with foliar decay disease of coconut palm in Vanuatu. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:273–280. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-2-273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Randles JW, Miller DC, Morin JP, Rohde W, Hanold D. Localization of coconut foliar decay virus in coconut palm. Ann Appl Biol. 1992;121:601–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1992.tb03470.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Randles JW, Chu PWG, Dale JL, Harding R, Hu J, Katul L, Kojima M, Makkouk KM, Sano Y, Thomas JE, Vetten HJ, et al. Nanovirus. In: van Regenmortel MHV, et al., editors. Virus taxonomy: seventh report of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses. London: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Raymundo AD. Saving abaca from the onslaught of the bunchy-top disease. Philipp Agric Sci. 2000;83:379–385. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raymundo AD, Bajet NB, Sumalde AC, Cipriano BP, Borromeo R, Garcia BS, Tapalla P, Fabellar N. Mapping the spread of abaca bunchy-top and mosaic diseases in the Bicol and Eastern Visayas Regions, Philippines. Philipp Agric Sci. 2001;84:352–361. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rochow WF, Duffus JE. Luteoviruses and yellows diseases. In: Kurstak E, editor. Handbook of plant virus infections and comparative diagnosis. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical; 1981. pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rohde W, Randles JW, Langridge P, Hanold D. Nucleotide sequence of a circular single-stranded DNA associated with coconut foliar decay virus. Virology. 1990;176:648–651. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90038-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rohde W, Beacker D, Randles JW. The promoter of coconut foliar decay-associated circular single-stranded DNA directs phloem-specific reporter gene expression in transgenic tobacco. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:623–628. doi: 10.1007/BF00019328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roy-Barman A. Genome characterisation and detection of a nanovirus associated with the foorkey disease of large cardamom. MSc Thesis, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi; 2009.

- 85.Sanderfoot AA, Lazarowitz SG. Cooperation in viral movement: the geminivirus BL1 movement protein interacts with BR1 and redirects it from the nucleus to the cell periphery. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1185–1194. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sano Y, Wada M, Hashimoto Y, Matsumoto T, Kojima M. Sequences of ten circular ssDNA components associated with the milk vetch dwarf virus genome. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:3111–3118. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-12-3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sharman M, Thomas JE, Skabo ST, Holton A. Abaca bunchy top virus, a new member of the genus Babuvirus (family Nanoviridae) Arch Virol. 2008;153:135–147. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-1077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shirasawa-Seo N, Sano Y, Nakamura S, Murakami T, Seo S, Ohashi Y, Hashimoto Y, Matsumoto T. Characteristics of the promoters derived from the single-stranded DNA components of Milk vetch dwarf virus in transgenic tobacco. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:1851–1860. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Singh SJ. Viral diseases of banana. New Delhi: Kalyani Publisher; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Smith PR. A disease of French beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) caused by subterranean clover stunt virus. Aust J Agric Res. 1966;17:875–883. doi: 10.1071/AR9660875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Su HJ, Wu RY. Characterisation and monoclonal antibodies of the virus causing banana bunchy top. Taipei: ASPAC Food and Fertiliser Technology Center; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Thomas JE, Dietzgen RG. Purification, characterization and serological detection of virus-like particles associated with banana bunchy top disease in Australia. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:217–224. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-2-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Timchenko T, Kouchkovsky F, Katul L, David C, Vetten HJ, Gronenborn B. A single rep protein initiates replication of multiple genome components of faba bean necrotic yellows virus, a single-stranded DNA virus of plants. J Virol. 1999;73:10173–10182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10173-10182.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Timchenko T, Katul L, Sano Y, de Kouchkovsky F, Vetten HJ, Gronenborn B. The master Rep concept in nanovirus replication: identification of missing genome components and potential for natural genetic reassortment. Virology. 2000;274:189–195. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Timchenko T, Katul L, Aronson M, Vega-Arreguin JC, Ramirez BC, Vetten HJ, Gronenborn B. Infectivity of nanovirus DNAs: induction of disease by cloned genome components of Faba bean necrotic yellows virus. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1735–1743. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Varma PM, Capoor SP. ‘Foorkey’ disease of large cardamom. Indian J Agric Sci. 1964;34:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vega-Arreguín JC, Gronenborn B, Ramírez BC. Arabidopsis thaliana is a host of the legume nanovirus Faba bean necrotic yellows virus. Virus Res. 2007;128:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vetten HJ, Chu PWG, Dale JL, Harding R, Hu J, Katul L, Kojima M, Randles JW, Sano Y, Thomas JE. Nanoviridae. In: Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editors. Virus Taxonomy: Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. London: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2005. pp. 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vishnoi R, Raj SK, Prasad V. Molecular characterization of an Indian isolate of Banana bunchy top virus based on six genomic DNA components. Virus Genes. 2009. doi:10.1007/s11262-009-0331-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Wanitchakorn R, Harding RM, Dale JL. Banana bunchy top virus DNA-3 encodes the viral coat protein. Arch Virol. 1997;142:1673–1680. doi: 10.1007/s007050050188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wanitchakorn R, Hafner GJ, Harding RM, Dale JL. Functional analysis of proteins encoded by banana bunchy top virus DNA-4 to -6. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:299–306. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wu RY, Su HJ. Transmission of banana bunchy top virus by aphids to banana plantlets from tissue culture. Bot Bull Acad Sin. 1990;31:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wu RY, Su HJ. Purification and characterization of banana bunchy top virus. J Phytopathol. 1990;125:153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1990.tb04261.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wu RY, You LR, Soong TS. Nucleotide sequences of two circular single-stranded DNAs associated with banana bunchy top virus. Phytopathology. 1994;84:952–958. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xie WS, Hu JS. Molecular cloning, sequence analysis, and detection of banana bunchy top virus in Hawaii. Phytopathology. 1995;85:339–347. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-85-339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yeh HH, Su HJ, Chao YC. Genome characterization and identification of viral-associated dsDNA component of banana bunchy top virus. Virology. 1994;198:645–652. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]