Abstract

Peanut is one of the most important oil and protein producing crops in the world. Yet the amounts of peanut processing by-products containing proteins, fiber and polyphenolics are staggering. With the environmental awareness and scarcity of space for landfilling, wastes/by-product utilization has become an attractive alternative to disposal. Several peanut by-products are produced from crush peanut processes and harvested peanut, including peanut meal, peanut skin, peanut hull and peanut vine. Some of peanut by-products/waste materials could possibility be used in food processing industry, The by-products of peanut contain many functional compounds, such as protein, fiber and polyphenolics, which can be incorporated into processed foods to serve as functional ingredients. This paper briefly describes various peanut by-products produced, as well as current best recovering and recycling use options for these peanut byproducts. Materials, productions, properties, potential applications in food manufacture of emerging materials, as well as environmental impact are also briefly discussed.

Keywords: Peanut meal, Peanut skin, Peanut hull, Peanut vine, Nutritional components

Introduction

The introduction of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultivation coincides with the expansion of the Mediterranean civilizations. Peanut is an important crop grown in the worldwide, originating in South American, the peanut spreads beyond the Mediterranean, such as China, Africa, Indian, Japan and United States of America. Most peanuts grown in the world are used for oil production, peanut butter, confections, roasted peanuts and snack products, extenders in meat product formulations, soups and desserts (Rustom et al. 1996). The substantial amounts of by-products are generated in the process of peanut harvest and peanut oil extraction, which are potential pollutants. However, only a few in these by-products is used as animal feed, and treated as a fertilizer. A large portion of peanut meals, skins, hulls, and vines is regarded as the agriculture wastes. At present, many researchers focus on the investigation of producing edible oil and kernel. Thus, very little attention is given to the by products of peanut. Especially, no report has been found on examining the possibility of peanut vine utilization. These peanut byproducts easily lead to environmental contamination. Therefore, if the nutritional compositions of peanut by-products are recovered and recycled, it can represent a significant economic and social benefit (Nepote et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2005).

Recently, the nutritional composition application of peanut by-products with market demands has been changed. During the last 20 years, new scientific research is focused on as following. Firstly, the value of peanut by-products is optimized. Secondly, the peanut proteins, peanut phenolic compounds, peanut edible fibre and their potential effects in the diet are characterized and quantified. Thirdly, the effects of nutritional composition from peanut by-products on human performance and product quality in food processing are studied. The information is essential in order to optimize the utilization of vegetable by-products in food processing. The special interest indicates that the peanut nutritional value may affect the human health. But the topics require further investigation.

This review paper briefly describes various peanut byproducts produced, as well as current best recycling use options for these materials. Materials, productions, properties, potential applications in food manufacture of emerging materials, as well as environmental impact are also presented. The aim is to encourage further research on edibility of peanut by-products for human being.

Peanut production

The land area occupied by peanut has increased in recent years, largely in response to the worldwide rise in peanut oil consumption. Globally peanut and peanut oil production was shown Table 1 in 2000/01-2010/12 (FAS-USDA web, 2011). As shown Table 1, peanut is an important crop grown on over 20 million ha in worldwide, ranking second with respect to planting area after rapeseed in oil plants. The peanut production in world is about 33 million tons per annual since 2000/01 (FAS-USDA web, 2011). The production range of peanut oil was from 4.52 to 5.14 million metric tons in 2000–2010, the average production was 4.86 million metric tons. The world production of peanut oil has risen from 4.53 million metric tons in 2000 to 4.91 in 2010. Production across the countries of the world, where China (44%), Indian (20%), and Nigeria (11%) are the largest producers, is expected to account for almost 75% of the world’s peanut oil (FAS-USDA 2011). In China, the plant area (4.45 million hectares) is only in the second place, the production of peanut is the maximum in the world, second to annual production of soybeans and above 14.34 million metric tons per year (FAS-USDA 2011).

Table 1.

World-wide peanut area, peanut production, crush peanut production, oil production and protein meal production in 2000/01-2010/12 (FAS-USDA 2011)

| Year | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut area (Million hectares) | 23.33 | 23.01 | 22.74 | 22.85 | 23.59 | 23.60 | 22.23 | 23.10 | 23.18 | 20.18 | 21.11 |

| Peanut production (Million metric tons) | 31.43 | 33.81 | 30.82 | 32.61 | 33.15 | 33.14 | 31.03 | 32.59 | 34.47 | 32.98 | 34.05 |

| Crush peanut production (Million metric tons) | 14.36 | 16.06 | 14.35 | 15.59 | 15.48 | 15.99 | 14.13 | 15.10 | 15.42 | 14.39 | 15.11 |

| Production of peanut oil (Million metric tons) | 4.53 | 5.14 | 4.52 | 5.03 | 5.05 | 4.93 | 4.77 | 4.95 | 4.97 | 4.67 | 4.91 |

| Peanut protein meal production (Million metric Tons) | 5.40 | 6.06 | 5.38 | 5.86 | 5.73 | 6.01 | 5.48 | 5.94 | 6.07 | 5.66 | 5.94 |

Peanut by-products

By-products derived from the harvested peanut and peanut oil extractions are generally known as “peanut by-products”. The different by-products considered in this review are defined as follows.

Peanut meal

Most peanuts grown in world are primarily used to produce edible oil. The average production of crush peanut around the world is about 14.09 million metric tons from 2000 to 2010 (FAS-USDA 2011). Peanut meals are well separated from peanut kernel after oil extraction. This separation results in another by-product, peanut pulp. Oil extraction also produces waste water, which can result in the pollution of environment. The average production of peanut meal all over the world is 5.78 million metric tons from 2000 to 2010 (FAS-USDA 2011). After the peanut oil is extracted, the protein content in the cake can reach 50%. It also contains other functional components, such as peanut lectin, resveratrol and piceid etc. (Sales and Resurreccion 2009). Generally, the peanut meals are divided into the fresh or dry meal. Different terms may be defined depending on different factors such as oil content (crude or extracted peanut meal) or moisture. The different oil extraction procedures, including causing peanut by-products, have recently been documented by Yu et al. (2007). It is worth distinguishing between cold and hot peanut meals, which are crushed by three and two-phase centrifugation extraction procedures, respectively. By comparision with the traditional extraction oil system (hot crushing), the peanut meals of cold crushing procedure contain the higher moisture and lower oil content. In addition, the cold crushing procedure also is a more efficient and environmentally friendly processing for extraction peanut oil. For 1000 kg of peanut for the cold procedure can generate 700 kg of peanut meals, while the hot crushing procedure can produce 500 kg.

Peanut skin

The kernels are used to make peanut butter, roasted snack peanuts, peanut confections, and peanut oil. An estimated 35–45 g of peanut skin is generated per kg of shelled peanut kernel. Over 0.74 million metric tons of peanut skins are produced annually worldwide as a by-product of the peanut processing industry (Sobolev and Cole 2003). Usually, only a little peanut skins are uilized to extract polyphenolic compounds or make the cattle feed, most of the skins are as the wastes of peanut processing industry and discarded (Sobolev and Cole 2003). It is well known that the peanut skins contain potent rich antioxidants. So, the more efficient utilization of peanut skins benefit industy and the economy, and the exploitation of peanut skins as a renewable raw material for antioxidant compounds will provide protection and enhancement of the environment. While peanut skins can provide an inexpensive source of polyphenols for use as functional ingredients in foods or dietary supplements, and make a positive contribution to the nation’s health (Yu et al. 2006).

Peanut hull

The peanut hulls obtained when graded peanuts are passed through shelling machines resulting in peanut kernels and hulls, which are an abundant agricultural by-product in world, especially in China. The production of peanut hull has been estimated to be 230–300 g of peanut hull per kg of peanut. It has been estimated that the land resources of the China will be capable of producing at least 5.0 million metric tons per year (Wang and Xu 2008). Peanut hulls may create a significant waste disposal problem around the area where peanut is grown and/or processed, which will polluted enviroment. So the peanut hulls should be further disposed. Another alternative is the use of destructive techniques such as incineration. The peanut hulls are plenty, inexpensive, and a renewable resource. It is interesting that peanut hulls are a richer source of diety fibre and other biological activity components, therfore peanut hulls are gaining status as a useful commodity. But peanut hulls cannot be efficiently and economically transported over long. distances to areas where they can be effectively utilized.

Peanut vine

The peanut vines include root, stem, leaves and flowers. Recent works have highlighted the role of functional compounds of the peanut kernel, skin and hull, while neglect the functional components of peanut root, stem, leaves and flowers for a variety of reasons. The yield of peanut vine generated annually worldwide as a by-product of the peanut industry is much more than the peanut kernel, skin and hull. The production of peanut vine from harvested peanut has been estimated to be 60–65% of the peanut production. Peanut vines are rich in diety fibres and flavonoid compounds (Du and Fu 2008). However, very limited information is available to the functional components from penaut vines.

Preservation

Given that the production of peanut by-products is seasonal their use in food processing or animal feeding over the whole year requires adequate preservation and storage. Drying may preserve peanut skins, peanut hulls and peanut vines but excess drying may decrease intake and nutritive value. Conversely, the main constraints to preserve peanut meals are water and oil contents. According to previous mycological surveys, peanuts are frequently contaminated by the fungal species Aspergillus flayus link, which can produce the aflatoxin (Achar et al. 2009). This infection can occur during transportation or storage of peanut meals. Aflatoxins are highly toxic and carcinogenic secondary metabolites of concern in food safety (Achar et al. 2009). In addition, it is well recognised that oxidation of the lipid fraction of peanut meals is a major cause of deterioration in fatty peanuts due to the high degree of fatty acid unsaturation (Talcott et al. 2005). Polyunsaturated fatty acids, specifically linoleic and linolenic acids, are very susceptible to oxidation even under mild ambient conditions and are easily incorporated into the chain mechanism of lipid peroxidation, to yield free and peroxy radicals (Talcott et al. 2005). Lipid oxidation is usually implicated as the primary cause of decreased shelf life, adverse tastes, loss of nutrients and generation of undesirable aromas during extended storage of peanut meals (Reed et al. 2002). So, it is important to develop preservation methods for the peanut meal. At present, no information about the preservation of peanut meals is available. The current study concerned storage of peanut meals in world where poor storage practice leads to heavy deterioration caused by fungi and fatty acid oxidation. However, silage storage may be a simple, cheap, and efficient procedure to preserve peanut meals. The inclusion of peanut meals, even those with moisture and oil, into multi-nutrient blocks has proved to be a promising way for their utilization (Yu et al. 2007; Jamdar et al. 2010).

Chemical composition

Table 2 summarizes the functionality and average chemical composition (dry matter) of peanut by- products. Peanut processing byproducts potentially represent a rich source of natural proteins, flavonoids and fibres etc., owing to the large amount of meals, peels and hulls produced. There are plentiful proteins in peanut meals, which contains 50–55% high quality protein (Wu et al. 2009) . The high concentration of polyphenols present in peanut skins support the utilization of agricultural by-products as source of natural antioxidants. The total phenolic content in defatted peanut skin is about 140–150 mg/g dry skin (Nepote et al. 2002), the non-defatted peanut skin is about 90–125 mg/g dry skin (Yu et al. 2005). Peanut hulls or vines are rich in diety fiber. The total Luteolin and edible fiber of peanut hulls is about 0.25–1.12 mg/g and 60% dry hulls (Akgül and Tozluo ğlu 2008; Tang et al. 2005). The total resveratrol of peanut roots is about 94.3–179.5 μg/g (Xiang et al. 2005).

Table 2.

Functionality and average chemical composition (dry matter) of peanut by- products

| Peanut chemical composition | Amounts | Functionality | references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | 50–55% | water holding/oil binding capacity, emulsification capacity, foam capacity, viscosity and gelation etc. | Yu et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2009 |

| Fiber | 60–70% | Water/oil holding capacity, viscosity, bulk, ferment-ability, and the ability to bind bile acids etc. | Akgül and Tozluo ğlu 2008; Girgis et al. 2002; Oliveira et al. 2009 |

| Phenolic compounds in including phenolic Acids, flavonoids and stilbene | 90–150 mg/g | Antioxidants, decrease/inhibit lipid peroxidation of LDL cholesterol and increase free radical scavenging capacity etc. | Nepote et al. 2002; Nepote et al. 2004; Yu et al. 2005; Rajaei et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2006 |

Peanut protein

Most peanuts grown in world are primarily used to produce edible oil. After the peanut oil is extracted, the protein content in the cake could reach 50%. The increasing demand for animal proteins (milk and meat) around the world has promoted the search for new sources of proteins. Peanut proteins constitute an interesting alternative due to their high nutritional value, functional properties and low cost. The latter is critically needed in many developing countries, because animal protein is more expensive and is getting beyond the reach of many people in developing countries. The abundant proteins of peanut are a cheap source of proteins, and can meet the requirements of many people.

Since 1990 the gold standard for measuring protein quality is the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS). According to PDCAAS, peanut proteins and other legume proteins such as soy proteins are nutritionally equivalent to meat and eggs for human growth and health (FAO 1991). The amino acid profile of the peanut meals shows that it can be an ingredient for protein fortification (Yu et al. 2007).

The peanut proteins had good emulsifying activity, emulsifying stability, foaming capacity, excellent water retention and high solubility, and would also provide a new high protein food ingredient for product formulation and protein fortification in food industry (Wu et al. 2009). Therefore, the peanut proteins can be regarded as one of the most attractive and promising vegetable proteins. Among plant proteins, the functional properties of soy proteins are the most extensively studied (Hua et al. 2005). Many investigations had been carried the functional properties of soy protein fractions, chemical and biochemical modified soy proteins (Jung et al. 2005). Adequate modification on proteins may improve their functional properties, so detailed investigation of peanut proteins is necessary to elucidate the functional properties of peanut proteins. Similar process was also found to enhance the solubility and other functional properties of peanut proteins. Yu et al. (2007) reported that the peanut flour by fermented treatment and peanut protein concentrate (PPC) could enhance the functional properties of peanut proteins and peanut flour. Functional properties of many other plant protein concentrates/isolates produced from peas and beans were also studied by a number of investigators (Lawal 2004). Functional properties of peanut protein have been the subject of limited studies (Yu et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2009). Among plant proteins, the nutritional value of peanut proteins is lower than soy proteins, but the anti-nutritional factor content of peanut proteins is less than that of soy proteins. So it is important to study the functional properties of protein concentrates/isolates.

Other than contribution from proteins, peanut meals likely possess few other compounds in significant quantities that will impact functionality of peanut proteins, such as polysaccharides. Polysaccharides in manufactured products can improve structure and stability, but it will reduce in vivo and vitro protein digestibility and and nutrient absorption (Mouécoucou et al. 2004). The decrease of protein digestibility by polysaccharides is often explained by the interactions between these two macromolecules that prevent the protein hydrolysis (Mouécoucou et al. 2004). But little information is available on peanut polysaccharides that actually contribute to total functional properties.

The methods of conventional industrial processing peanut oil involve crushing and solvent extraction. Thus, very little attention is given to the protein residue. Due to the denaturizing of protein or residual solvent, the protein residue is mainly used in the manufacture of compound feed stuffs or fertilizer. Although it has been recongnized that the peanut protein resource is one of important plant proteins, it can not been utilized reasonably. Recently, many researchers focus on exploring new technologies to separate peanut proteins and oil.

Traditionally, the separation of peanut proteins had been done by isoelectric precipitation, alcohol precipitation, isoelectric precipitation with alcohol precipitation, hot water extraction and alkali solution with isoelectric precipitation (Yu et al. 2007). Table 3 summarizes the pros and cons of existing preparation methods of peanut protein concentrates/isolates. However, the methods have some fatal defects. For example, a great deal of wastewater produced causes serious environmental pollution, and it is also limited capacity of raw material treatment and high consumption of acid and alkali. Moreover, it is easy to cause protein denaturation. Therefore, it is necessary to explore an alternative extraction approach of peanut proteins.

Table 3.

Process methods of peanut protein concentrates/isolates

| Preparing sample | Method | Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut protein concentrates | Isoelectric precipitation | Better functional properties, worse color and flavor, lower extraction efficiency, severe contamination for environment | Liu et al. 2001 |

| Yu et al. 2007 | |||

| Wu et al. 2009 | |||

| Aqueous precipitation | Poor functional properties, protein denaturation, lower extraction efficiency | Yu et al. 2007 | |

| Wu et al. 2009 | |||

| Alcohol precipitation | Better color and flavor, poor functional properties, lower nitrogen solubility index | Yu et al. 2007 | |

| Wu et al. 2009 | |||

| Isoelectric precipitation and alcohol precipitation | Better color and flavor, poor functional properties, lower nitrogen solubility index | Yu et al. 2007 | |

| Wu et al. 2009 | |||

| Hexane and aqueous alcohol precipitation | Better functional properties, higher nitrogen solubility index, lower coefficient of solvents recovery | Yu et al. 2007 | |

| Ultrafiltration (UF) | no need for any chemicals, higher yield and superior functional properties of the UF protein product non-thermal and non-chemical nature of the UF process, membrane easily contaminated and be difficult to clean | Krishna Kumar et al. 2004 | |

| Peanut protein isolates | Alkali solution and isoelectric precipitation | Better functional properties, higher extraction efficiency, severe contamination for environment | Dumay et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2009 |

| Ultrafiltration (UF) | No need for any chemicals, higher yield and superior functional properties of the UF protein product non-thermal and non-chemical nature of the UF process, membrane easily contaminated and be difficult to clean | Krishna Kumar et al. 2004 |

Alternatively, some auxiliary methods are designed to improve extraction efficiency of proteins, such as enzyme, superfine grinding, radiation, microwave and ultrasonics (US) processing et al. (Quist et al. 2009). The search for ideal processing technologies continues in extraction of protein, but there is still no solution to the fundamental problems, which require a sound approach to simultaneously address the issues of safety, extraction rate, product qualities, and consumer acceptance. Krishna Kumar et al. (Krishna Kumar et al. 2004) reported that a new protein extraction method employing a polymeric spiral wound and tubular ultrafiltration (UF) modules, used for the producing soy protein concentrates, was developed for the application of and non-thermal and nonchemical processing. In comparison to the conventional extraction technique, the new processing method has the advantage of higher yield and superior functional properties of the UF protein product non-thermal and non-chemical nature of the UF process, and is more versatile for extracting various proteins.

Structural changes of proteins in food can affect by their functional properties. Some modifications on structure of proteins may well have different their functional properties compared to the native proteins (Jung et al. 2005). The modification methods include physical (high pressure, heat or mild alkali treatment), chemical (acylation, phosphorylation and deamidation), and enzymatic extraction methods (Hua et al. 2005; Jung et al. 2005; Dumay et al. 2006). The changes of functional properties of proteins depend on modification methods and many parameters of the extraction medium, as well as downstream processing of extracted proteins such as purification and drying factors need to be addressed. The effect of ionic strength, pH, heat, ionic strength and water on functional properties of proteins have been widely studied (Lakemond et al. 2003). However, limited information is available in the literature on the effect of processing on the functional properties and application in food products of peanut proteins (Yu et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2009).

Peanut polyphenolic compounds

Peanut potentially represent a rich source of natural procyanidin, owing to the large amount of peanut byproducts produced. Such as peanut peels contain a high concentration of phenolic compounds (Nepote et al. 2002; Nepote et al. 2004). Limited studies suggest that peanut skins may contain potent procyanidin compounds (Nepote et al. 2004; Yu et al. 2006).

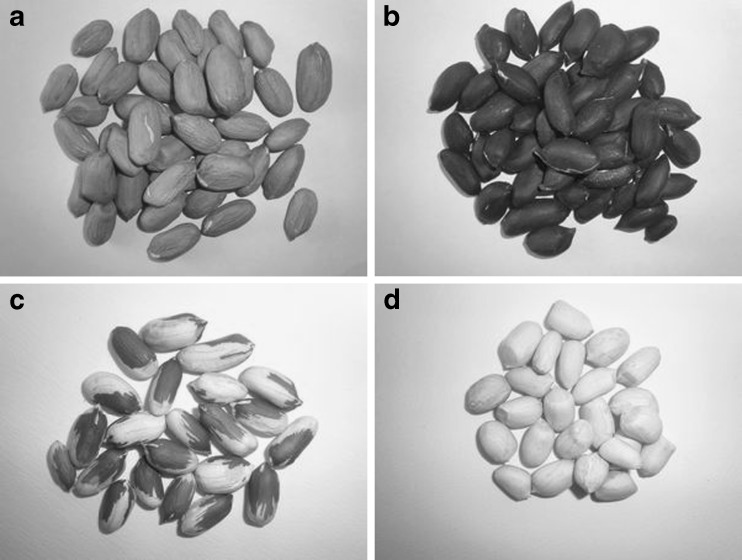

Moreover, the procyanidin in fruits and vegetables, grape seeds and grape skin have been recognized as natural antioxidants and extensively studied for their health promoting effects, such as cancer prevention, cardiovascular disease prevention, and anti-inflammatory activities (Hammerstone et al. 2000). The peanut skins have pink-red, black, white and multicolored color (Fig. 1) and an astringent mouth feel when consumed. They are typically removed before peanut consumption or inclusion in confectionary and snack products. Skins are established to be a rich source of phenolic compounds, including various procyanidins (Yu et al. 2005). It suggests that peanut skins are excellent potential to produce neutraceutical ingredients (Nepote et al. 2004; Yu et al. 2005). However, there is a wealth of literature information on health benefits of phenolics in wine, very few if any studies are available on the health promoting compounds. It is found that the researchers have focused on the extraction of polyphenols and antioxidants from peanut pink-red skin (Nepote et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2006), while little information is available in the literature on the phenolics of black, multicolored and white color peanut skin. It is important to realize that the phenolic compounds from peanut skins can be used as potent natural antioxidants in food systems besides positive biological effects in humans consuming them (Sobolev and Cole 2003). It was reported that the peanut red skins contain 17% proanthocyanidins (by weight of skins), 50% of which were soluble in ethyl acetate, making up of low and high molecular weight oligomers (Karchesy and Hemingway 1988). Six A-type procyanidins were identified, which were found to inhibit the activity of hyaluronidase, which causes inflammation (Lou et al. 2004). Catechins, β-type procyanidin dimers, procyanidin trimers, tetramers, and oligomers with higher degree of polymerization were also reported to be present in peanut skin (Lazarus et al. 1999). Yu et al. (2006) identified and quantified catechins, A-type and B-type procyanidin dimers, trimers and tetramers in chemically purified peanut skin extracts using reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). However, the quantitative analysis of catechins and procyanidins of black, multicolored and white color peanut skin has not been reported in the literature.

Fig. 1.

Different color skin peanut: a, red-skin; b, black-skin; c, multicolored -skin; d, white-skin

Recently, several published studies have shown that the peanut root and skin contains the resveratrol (Medina-Bolivar et al. 2007). Resveratrol (3,5,4-trihydroxystilbene) is a polyphenol present in a variety of plant species, e.g. peanuts, berries, grapes, some pine trees and most recently tomato fruit skin (Ragab et al. 2006), and thought to possess chemopreventive properties (Aggarwal et al. 2004).

Up to now, several conventional extraction techniques have been reported for the extraction of phenolics from peanut byproducts. Typically, the phenolics from peanut byproducts have been extracted using hot water, aqueous methanol (MeOH) (Yu et al. 2005), ethanol (EtOH) (Talcott et al. 2005). Nepote et al. (2002) optimized the extraction conditions for the best recovery of antioxidant compounds from peanut skins. It was obtained that the extract content of peanut skin could be affected ethanol proportions, skin particle sizes, proportions of solvent/skins and extraction time. Yu et al. (2005) had evaluated hot water, 80% MeOH and 80% EtOH, all with to extract the phenolics from peanut skin using a mix- stirring technique. Water, in general, is the worst extraction solvent for the peanut skin tested. In addition, there were some reports about the effects of skin removal methods (direct peeling, blanching, and roasting) on total phenolics and total antioxidant activities (TAA) of peanut skin extracts (Nepote et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2005). Results showed that both skin removal methods and extraction solvents had significant effects on total extractable phenolics and TAA, with the combination of roasting and ethanol extraction being the most efficient recovery method. The phenolics of different parts of the peanut vine have also been reported by Du and Fu (2008). The investigates potentially offer the information of resveratrol source. Peanut kernel and hull has been reported to contain antioxidant components, such as flavonoids, procyanidin et al. (Rajaei et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2006). The results indicate that the antioxidant components may exist in the plant hulls.

Although there is an abundant source of these health-promoting compounds, peanut meals, skins, vines and hulls have not been exploited as valuable natural resources. The development of more efficient methods for extracting phenolics from peanut byproducts is imperative in order to increase commercial appeal. Seeking more environmentally friendly methods and increased productivity, newer extraction techniques have been developed, such as aqueous two-phase extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, enzyme-assisted, γ-irradiation-based, microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) (Khan et al. 2010; Štĕrbová et al. 2004; Zu et al. 2009). For instance, aqueous two-phase systems (ATPS) were widely applied in the extraction of biomolecules (Chethana et al. 2007). ATPS has potential to achieve the desired purification and concentration of the product in a single step. In recent years, it is applied in the extraction and purification of phenolics. Chethana et al. (2007) reported that aqueous two-phase extraction was employed for the first time as an attractive alternative for the downstream processing of betalains, mainly for the removal of sugars without the need of additional steps. The results showed that differential partitioning of betalains and sugars was achieved in aqueous two phase extraction at a higher tie line (34%), wherein 70–75% of betalains partitions to the top phase and 80–90% of sugars present in the beet partitions to the bottom phase. Maybe, the peanut phenolics can be successfully separated from the polymer employing aqueous two-phase extraction.

Traditional separation and purification techniques of phenolic compounds, including a solvent extraction of the sample (e.g. in a Soxhlet extractor) followed by liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) or column chromatography on different sorbents, microbial fermentations, High-speed Countercurrent Chromatography (HSCCC) and molecular imprinting technology (MIT), are well-known procedures applied to isolate and purify of plant phenolics (Savitri Kumar et al. 2009). However, very few studies were avaiable on the purification of peanut polyphenolics (Yu et al. 2006).

Dietary fibre

The largest content of functional components in peanut hulls and vines is the dietary fibres, and the dry weight content is over 60%. The dietary fibres constitute an interesting alternative due to their high nutritional value, functional properties and low cost. The value of consuming dietary fibres is largely due to various physiological effects that have important health implications, such as reducing the risk of colon cancer for laxation, blood cholesterol and the overall glycemic response for glucose attenuation (AACC 2001). An estimated total of over 10 million metric tons of peanut hulls are generated annually worldwide as a by-product of the peanut industry. The common characteristics of the various dietary fibres are indigestible in the human small intestine. So, it is necessary that the fibre characteristics are modified by processing treatments, such as grinding or extrusion, enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation to improve functionality of dietary fibers. Milling and fractionation of peanut hulls can isolate important dietary fibre components for incorporation into commercial food products to enrich their fiber content and/or serve as functional ingredients. Expanding peanut hull utilization in food products can serve to enhance human health, and increases the market value of the crops. The superfine grinding technology plays an important role in application in the processing of dietary fibres (Zhao et al. 2009a, b). The superfine grinding technology can improve the taste smooth and delicious of the dietary fibre production, and increase the solubility, dispersibility, absorbility and bioactivity (Zhao et al. 2009a, b). In the whole, the application of dietary fibres will be enlarged in food or feed industry by the superfine milling technology.

Because the peanut hulls consist of some constituent polymers: cellulose, hemicelluloses, pectin, lignin and protein, ground peanut hull powder can be as a low-cost adsorbents for heavy metal or dye removal, such as copper and lead removal et al. (Oliveira et al. 2009). Some researchers treated peanut hull powder by procedures to get activated carbon using chemical activation (such as H2SO4 H3PO4, ZnCl2, KOH et al.) and physical activation (such as carbon dioxide or steam pyrolysis) methods (Girgis et al. 2002). Another potential utilization of peanut hulls can be as a fibre-peanut mixture to produce fiberboards (Akgül and Tozluo ğlu 2008). At present, limited information is provided about studies on the fibre compounds of peanut vines.

Conclusions

Although there were previous studies on the functional components and properties in peanut meals, skins, hulls and vines, commercial products of by-products are absent in food, feed, medicine and chemistry industry. It can be seen that within field of endeavor, the state of knowledge is not yet strong. From this discussion we can see that there are components of knowledge that origins in food or material science. The by-products of peanut industry can be processed by separation and purification technique or mechanical engineering. There is a need to grasp the developments of defects in peanut by-products, which will provide the basis of coursework for process engineering. However, the case histories reviewed should indicate the great interest and activity to study processing technology of peanut by-products. With modern techniques and ideas, there should certainly be an impetus from industry to help grapple with the difficult issues. Once th companies first gain an effective understanding of a process to make a product, they will have an opportunity to gain a significant advantage. The challenges and future directions of research for by-products of peanut to investigate the potential as food or feed additives are as follows. Firstly, initiating strong programs investigate the underlying functional components and properties of peanut by-products. Secondly, it is the most interesting in the potential applications of by-products with modern technology (such as superfine grinding technology, microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted technology, reverse micelle technology et al.) both directly as food or feed supplements for animal and human consumption, and indirectly, as potentially health-promoting byproducts in the meat supply, to offset and replace the carcinogenic effects of chemical food additives.

Most of us are familiar with the problems of hunger and malnutrition across the world, especially in developing countries. Problems with the world food supply remain a serious matter. It is receiving increasing attention by the WHO and other international aid agencies these days are an issue called the “epidemiological transition” by public health scientists. The epidemiological transition refers to a now well-established phenomenon that, as countries develop economically, there is a predictable shift in the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, from infectious diseases to chronic diseases, from diseases like malaria, cholera, polio and tuberculosis, to chronic diseases like cardiovascular heart disease, cancer, stroke and diabetes. With that as background, the development of by-products from peanut industry will make a significant contribution in all these areas in the years to come.

Acknowledgements

Financial support of this work by Promotive Research Fund for Excellent Young and Middle-aged Scientists of Shandong Province of China (Grant No. BS2010NY027).

References

- AACC Official Methods of Analysis. The definition of dietary fiber. Cereal Food World. 2001;46:112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Achar PN, Hermetz K, Rao S, Apkarian R, Taylor J. Microscopic studies on the Aspergillus flavus infected kernels of commercial peanuts in Georgia. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2009;72:2115–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB, Bhardwaj A, Aggarwal RS, Seeram NP, Shishodia S, Takada Y. Role of resveratrol in prevention and therapy of cancer: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:2783–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akgül M, Tozluo ğlu A. Utilizing peanut husk (Arachis hypogaea L.) in the manufacture of medium-density fiberboards. Bioresource Technol. 2008;99:5590–5594. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chethana S, Nayak CA, Raghavarao KSMS. Aqueous two phase extraction for purification and concentration of betalains. J Food Eng. 2007;81:79–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2006.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du FY, Fu KQ. Study on Total Flavonoids Contents in Peanut Vines of Different Plant Organs. Food Sci. 2008;1:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Dumay E, Pieart L, Regnault S, Thiebaud M. High pressure–low temperature processing of food proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:599–618. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protein Quality-Report of Joint. Rome: FAO/WHO Expert Consultation, FAO Food and Nutrition; 1991. p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Girgis BS, Yunis SS, Soliman AM. Characteristics of activated carbon from peanut hulls in relation to conditions of preparation. Mater Lett. 2002;57:164–172. doi: 10.1016/S0167-577X(02)00724-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerstone JF, Lazarus SA, Schmitz HH. Procyanidin content and variation in some commonly consumed foods. J Nutr. 2000;130:2086–2092. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.8.2086S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua YF, Cui SW, Wang Q, Mine Y, Poysa V. Heat induced gelling properties of soy protein isolates prepared from different defatted soybean flours. Food Res Int. 2005;38:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamdar SN, Rajalakshmi V, Pednekar MD, Juan F, Yardi V, Sharma A. Influence of degree of hydrolysis on functional properties, antioxidant activity and ACE inhibitory activity of peanut protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2010;121:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.12.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Murphy PA, Johnson LA. Physicochemical and functional properties of soy protein substrates modified by low levels of protease hydrolysis. J Food Sci. 2005;70:C180–C187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb07080.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karchesy JJ, Hemingway RW. Condensed tannins: (4b-8;2b-O-7)-linked procyanidins in Arachis hypogaea L. J Agric Food Chem. 1988;34:966–970. doi: 10.1021/jf00072a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MK, Abert-Vian M, Fabiano-Tixier AS, Dangles O, Chemat F. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols (flavanone glycosides) from orange (Citrus sinensis L.) peel. Food Chem. 2010;119:851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.08.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna Kumar NS, Yea MK, Cheryan M. Ultrafiltration of soy protein concentrate: performance and modeling of spiral and tubular polymeric modules. J Membrane Sci. 2004;244:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2004.06.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakemond CMM, de Jongh HHJ, Hessing M, Gruppen H, Voragen AGJ. Soy glycinin: influence of pH and ionic strength on solubility and molecular structure at ambient temperatures. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;48:1985–1990. doi: 10.1021/jf9908695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawal OS. functionality of African locust bean (Parkia biglobssa) protein isolate: effects of pH, ionic strength and various protein concentration. Food Chem. 2004;86:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus SA, Adamson GE, Hammerstone JF, Schmitz HH. High-performance chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of proanthocyanidins in foods and beverages. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:3693–3701. doi: 10.1021/jf9813642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DC, Zhang WN, Hu XH. The research on preparation and functional properties of peanut protein. Journal of Wuhan Polytechnic University. 2001;4:10. [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, Yuan H, Ma B, Ren D, Ji M, Oka S. Polyphenols from peanut skins and their free radical-scavenging effects. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:2391–2399. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Bolivar F, Condori J, Rimando AM, Hubstenberger J, Shelton K, O’Keefe SF, Bennet S, Dolan MC. Production and secretion of resveratrol in hairy root cultures of peanut. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:1992–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouécoucou J, Villaume C, Sanchez C, Méjean L. Effects of gum arabic, low methoxy pectin and xylan on in vitro digestibility of peanut protein. Food Res Int. 2004;37:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nepote V, Grosso NR, Guzman CA. Extraction of antioxidant components from peanut skins. Grasas Y Aceites. 2002;54:391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Nepote V, Mestrallet MG, Grosso NR. Natural antioxidant effect from peanut skins in honey-roasted peanuts. J Food Sci. 2004;69:s295–s300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2004.tb13632.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira FD, Paula JH, Freitas OM, Figueiredo SA. Copper and lead removal by peanut hulls: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Desalination. 2009;248:931–940. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2008.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quist EE, Phillips RD, Saalia K. The effect of enzyme systems and processing on the hydrolysis of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) protein. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2009;42:1717–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ragab A, Van Fleet J, Jankowski B, Park J, Bobzin S. Detection and quantitation of resveratrol in tomato fruit (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:7175–7179. doi: 10.1021/jf0609633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaei A, Barzegar M, Mobarez AM, Sahari MA, Esfahani ZH. Antioxidant, anti-microbial and antimutagenicity activities of pistachio (Pistachia vera) green hull extract. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed KA, Sims CA, Gorbet DW, O’Keffe SF. Storage water activity affects of flavor fade in high- and normaloleic peanuts. Food Research International. 2002;35:769–774. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(02)00073-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rustom IYS, Lopez-Leiva MH, Nair BM. Nutritional, sensory and physicochemical properties of peanut beverage sterilized under two different UHT conditions. Food Chem. 1996;56:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(95)00153-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Resurreccion AVA. Maximising resveratrol and piceid contents in UV and ultrasound treated peanuts. Food Chem. 2009;117:674–680. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.04.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savitri Kumar N, Maduwantha BWWMA, Kumar V, Nimal Punyasiri PA, Sarath BAI. Separation of proanthocyanidins isolated from tea leaves using high-speed counter-current chromatography. J Chrom A. 2009;1216:4295–4302. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobolev VS, Cole RJ. Note on utilization of peanut seed test. J Sci Food Agric. 2003;84:105–111. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Štĕrbová D, Matĕjĺček D, Vlček J, Kubáň V. Combined microwave-assisted isolation and solid-phase purification procedures prior to the chromatographic determination of phenolic compounds in plant materials. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;513:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2004.03.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talcott ST, Duncan CE, Pozo-Insfran DD, Gorbet DW. Polyphenolic and antioxidant changes during storage of normal, mid, and high oleic acid peanuts. Food Chem. 2005;89:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LP, Gong YQ, Wu XY, Rao GX. HPLC Determination of Luteolin of Peanut Hull from Different Regions. Journal of Peanut Science. 2005;34:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Xu H. Biological activity components and functionality in peanut hull. Food and Nutrition in China. 2008;12:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wu HW, Wang Q, Ma TZ, Ren JJ. Comparative studies on the functional properties of various protein concentrate preparations of peanut protein. Food Res Int. 2009;42:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2008.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang HY, Zhou CS, Lei QF, Xiao JB, Chen LS. Determination of resveratrol in peanut root by HPLC. Natural Product Research and Development. 2005;17:179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Yu JM, Ahmedna M, Goktepe I. Effects of processing methods and extraction solvents on concentration and antioxidant activity of peanut skin phenolics. Food Chem. 2005;90:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JM, Ahmedna M, Goktepe I, Dai J. Peanut skin procyanidins: Composition and antioxidant activities as affected by processing. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;19:364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JM, Aahmedna M, Goktepe I. Peanut protein concentrate: Production and functional properties as affected by processing. Food Chem. 2007;103:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Ao Q, Yang LW, Yang YF, Sun JC, Gai GS. Application of superfine pulverization technology in Biomaterial Industry. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers. 2009;40:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2008.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XY, Yang ZB, Gai GS, Yang YF. Effect of superfine grinding on properties of ginger powder. J Food Eng. 2009;91:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zu YG, Wang Y, Fu YJ, Li SM, Sun R, Liu W, Luo H. Enzyme-assisted extraction of paclitaxel and related taxanes from needles of Taxus chinensis. Sep Purif Technol. 2009;68:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2009.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]